In this section you will learn to:

- Identify key factors to be addressed in the policy development and implementation process.

- Take key organisational, professional, legal, and ethical considerations into account when planning, developing, and implementing policy initiatives.

Supplementary materials relevant to this section:

- Reading A: Clinical Governance for Allied Health Practitioners

- Reading B: Managing the Risk of Psychosocial Hazards at Work: Code of practice – Extract 1

- Reading C: Charter of Healthcare Rights

Welcome to CHCPOL002 Develop and Implement Policy!

In this unit, you will learn what you need to know to develop, review, implement, and continuously improve the policies, procedures, and other guiding documents that your staff use in their day-to-day work within your allied health practice. This is a key skill set for practice managers and key to meeting major priorities in any practice, such as support quality of service, identifying and addressing risks, and maintaining the sustainability of the organisation.

As in all of your units in this course, we have a practical focus, and most of the unit will involve working through the different steps in the policy development process. You will then have an opportunity to practice this in your assessments and you will apply what you have learned during your work placement.

Shortly, we will work through some underpinning responsibilities that need to be either explicitly addressed by or integrated within the policies, procedures, and other guiding documents that you develop. First, let’s get an overall sense of what policy development is and why it matters.

Policies are general guidelines or statements about how the organisation will function, including how it will meet legal obligations and sustain itself as a business, while procedures “create a roadmap showing how a policy can be implemented or how a service can be delivered. Procedures refer to the various types of tasks performed by employees, resources that are necessary, boundaries of the service, and contingency plans for executing an alternative if the policy cannot be implemented (plan B)” (O’Donnell & Vogenberg, 2012, p. 341). Specific areas of policy are designed in particular ways. For example, take this description of a human resource policy from the New South Wales (NSW) Government: the policy is “a statement which underpins how human resource management issues will be dealt with in an organisation. It communicates an organisation’s values and the organisation’s expectations of employee behaviours and performance.”

Policies are general guidelines or statements about how the organisation will function, including how it will meet legal obligations and sustain itself as a business.

It is important to note that, when we talk about policies, we are actually referring to both the policy (also known as the policy statement) and an attached set of procedures that support the policy’s enactment. When we talk about acting “in accordance with policy” or “following policy”, for example, we actually mean following the procedures attached to a given policy. So, when we refer to ‘policies’ in this unit, we generally mean policies and their procedures or other associated guiding documents.

Procedures "create a roadmap" showing how a policy can be implemented or how a service can be delivered. Procedures refer to the various types of tasks performed by employees, resources that are necessary, boundaries of the service.

Why Do Policies Matter?

Workplace policies and procedures guide the behaviour of staff and managers in areas that are critical to the legal, ethical, and professional responsibilities they hold and to the purpose of the organisation.

Well-written workplace policies:

- are consistent with the values of the organisation

- comply with employment and other associated legislation

- demonstrate that the organisation is being operated in an efficient and businesslike manner

- ensure uniformity and consistency in decision-making and operational procedures

- add strength to the position of staff when possible legal actions arise

- save time when a new problem can be handled quickly and effectively through an existing policy

- foster stability and continuity

- maintain the direction of the organisation even during periods of change

- provide the framework for business planning

- assist in assessing performance and establishing accountability

- clarify functions and responsibilities.

(NSW Government, n.d.)

(Just note that the NSW Government has overstated the power of policies in this extract: even the best-written policies can’t ‘ensure’ uniformity or anything else, but they promote appropriate behaviour by clearly communicating and guiding actions. As you become familiar with policy examples, you will find that the word ‘ensure’ is inappropriately used quite often! Similarly, while policies should guide staff behaviour in ways that is compliant with legislation, if the policies are not followed or enforced, the organisation is non-compliant.)

What Policies and Procedures Does My Practice Need?

Policies need to cover all key areas of organisational practice, with associated procedures to guide staff in carrying them out. These include staff and management responsibilities in relation to their work roles, clients, and each other; how information is collected, stored, and used; human resources – recruitment, professional development, supervision, and processes when worker behaviour is unacceptable; how the organisation upholds human rights, including anti-discrimination policies, as well as the rights of members of particular groups; work health and safety; management of complaints/grievances; financial management and processes within the organisation; and use of communications and other technologies.

Self-Reflection

Allied Health Support (2023) suggests asking yourself the following questions to identify policies your practice needs. Work through them and try to identify at least three major aspects that policy will need to cover in each area.

- What topics or areas do you to need cover, to address areas of clinical care in which there’s a need for clear guidelines and consistent processes to facilitate optimal service to clients? These will include things like onboarding and inducting new team members, report templates, consents, and client’ goal establishment and review.

- What areas of admin work need clear guidelines and consistent processes to ensure optimal support of your therapists AND clients? Examples include a client onboarding checklist, a welcome pack and payment guidelines.

- What’s needed to embed and drive the vision and values of your practice? For example, if “Quality” is one of your Values, how should this be shown by individual team members in their roles, in teams within your practice and the organisation overall?

- What is needed to meet legal, compliance and accreditation requirements? These cover your HR obligations, as well as things like privacy, IT and incident management.

- What will underpin performance – both staff and financial? Examples include position descriptions, performance appraisals, financial reports, budgets and decision tools.

Consider the guidance of the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality (ACSQHC) on Action 1.07: Policies and Procedures, one of their standards for allied health services:

Intent: The health service organisation has current, comprehensive and effective policies, procedures and protocols that cover safety and quality risks.

Reflective questions: How does the health service organisation ensure that its policy documents are current, comprehensive and effective? How does the health service organisation ensure that its policy documents comply with legislation, regulation, and state or territory requirements?

Key tasks

- Set up a comprehensive suite of policies, procedures and protocols that emphasise safety and quality.

- Set up mechanisms to maintain currency of policies, procedures and protocols, and to communicate changes in them to the workforce.

- Review the use and effectiveness of organisational policies, procedures and protocols through clinical audits or performance reviews.

- Periodically review policies, procedures and protocols to align them to state or territory requirements and ensure that they reflect best-practice and current evidence.

- Develop or adapt a legislative compliance system that incorporates a compliance register to ensure that policies, procedures and protocols are regularly and reliably updated, and respond to relevant regulatory changes, compliance issues and case law.

(ACSQHC, 2023)

Reading A

Within allied health practices specifically, policies need to guide the organisation in meeting key allied health responsibilities. Your first reading, the Allied Health Clinical Governance Framework, is one of the Key Actions for Health Services Organisations from ACSQHC (which is a very valuable series) outlines a series of such responsibilities. As you work through it, identify particular policies that would be needed in order to support staff and managers in meeting these responsibilities.

Watch

The policy development process is more of a cycle than a single process. This is because, for the most part, there will already be policies in place when we go to develop a policy initiative, so we won’t be developing a set of policies from scratch but will be addressing issues in the current set of organisational policies and procedures; these issues are often a lack of currency (i.e., aspects of existing policies are out-of-date) or gaps in the existing set of policy documents. So, the cycle often starts when notice that a policy or procedure is no longer relevant or is lacking in important ways.

Our first step is to evaluate the current policy documents and undertake research on what the current standards are. Relevant areas for consideration include legislation and regulation changes, updated codes of ethics or practice for allied health professions, community standards and expectations, and changing social or political conditions. We often need to consult others to evaluate where the policies, as they currently stand, are not meeting client or organisational needs, and to help identify the full range of potential options for rectifying this.

The second step is to draft a new potential policy or related document. Employing organisations generally use a specific format for policies, which we need to follow as we do this, so through this unit we will look at what policies must include and a several policy format examples. As we do our drafting, we need to address community and professional expectations, as well as the rights and responsibilities that we will shortly discuss. For example, we need to ensure that the rights of all key stakeholders are addressed and that the policy we draft is backed-up by good practice guidelines, legislation, or evidence-based guidance relevant to the area of policy development. We may also need to create links to other sources of information that support policy implementation, such as specific laws or professional requirements, or other policies that the new initiative will relate to. Finally, we need to consider how the policy will be implemented and develop a plan for sharing and testing the appropriateness of the policy before it is finalised and rolled out.

This brings us to step three: testing the draft policy. This isn’t just about sharing information with staff, but a comprehensive process whereby we can get the input of key stakeholders regarding the implementation of the policy and, in particular, what aspects of the policy can (or must) be improved.

In step four, we finalise our draft policy and put together whatever additional information, guidance, or plans the organisation and its stakeholders require in order to implement it, and present these to the decision-making body for the organisation (e.g., board, directors, a relevant committee). In the usual course of events, these decision-makers will be familiar with the draft policy because and will have been actively involved in (and may even have instructed us to start) the policy review process. Some, however, will not be familiar with the area or with the development process, so you need to be prepared to present and advocate for your policy initiative, because these decision-makers are the ones who will determine whether the draft initiative is ratified (that is, given formal approval and rolled out, either replacing an old policy or as a brand-new policy addressing an area that previously was not covered).

Finally, we roll out our policy implementation plan. In doing this, we need to make sure that sufficient time and resources are provided to everyone who will be involved in implementing the new policy such that they can do this effectively. We also need to keep channels of communication open, so that we are made aware of any issues with its implementation. This is where we start to see that the policy development process really is a cycle, because as feedback comes in that the new policy needs to be changed in some way – say, to better support implementation or to meet a responsibility we missed have not addressed – we go back to step one and start the process again.

At this point in your course, it won’t surprise you to learn that organisational policy and law, as well as key ethical considerations in the healthcare professions, are inter-related. So, let’s look at some core legal and ethical considerations that you will need to either explicit the address and your policies or ensure your policies are consistent with. Having already completed units in managing legal and ethical responsibilities, work health and safety, and risk management, you will probably find these familiar, but reviewing them here will help you ‘connect the dots’ between these considerations and the policies you develop.

Duty of Care Versus Negligence

Duty of care doesn’t just apply to professionals. In fact, duty of care is their responsibility held by every adult in the community in some manner. But we are not concerned with this broad definition of duty of care here. Rather, we are concerned about the duty of care that healthcare professionals or the general staff of healthcare practices owe, primarily to their clients, but also to one another, to site visitors, and to members of the general public. In the allied health setting, our major duty of care is our responsibility that each professional in the practice has to provide (or support provision of) services that are appropriate to clients and to avoid actions that could be harmful to clients or relevant others.

The first responsibility – to do things that are in the interests of or promote the safety of another person - is what we might call a positive responsibility because it relates to what we do. The second – the responsibility to avoid acts that could cause harm to others – is what we might call a negative responsibility, in that it relates to what we do not do. The importance of both types of duty of care can be clarified with examples. We can enact the positive responsibility when we make sure that our premises are safe to access, for example, while we meet the negative responsibility by not undertaking risky tasks that are beyond our work-role boundaries or professional competencies. Similarly, the healthcare professional might meet their positive responsibility by contacting another service provider when a client needs additional interventions that the practitioner doesn’t provide, and meets their negative responsibility by refusing to provide interventions that could harm the client.

Where duty of care responsibilities are not met, this is known as negligence. And, just as there are two types of responsibility in duty of care, there are two ways that we can be negligent. We can either be negligent through what we do (that is by placing a client or other relevant person at risk through some action we’ve taken) or place the person at risk or cause them harm by failing to do something that it is with in our responsibility to do. Again, we can clarify these with examples. Passing on inaccurate information about a client to their health care provider and thereby negatively impacting their treatment would be negligence through something we do, while failing to undertake appropriate risk management processes in setting up or maintaining the practice setting could lead to harm, in which case we would have been negligent through our failure to meet our responsibilities.

Policy Development and Duty of Care

Duty of care is absolutely essential to many of the policies you will develop. Many policies, and their associated protocols, are directly aimed at supporting workers and the organisation to meet their duty of care responsibilities and avoiding negligence. For example, policies and procedures relating to direct client service include responsibilities and processes that are essential to protecting clients and avoiding harm; work health and safety (WHS) policies and procedures aim to reduce physical and psychology risks to workers, clients, and site visitors; child protection policies and procedures aim to uphold our duty of care to children; and so on. This means that you need to be familiar with duty of care and able to integrate up-to-date standards and practices for meeting duty of care responsibilities within the policy initiatives you undertake. So, where will you find this information?

There are two primary ways that we can find information about what is considered appropriate in terms of enacting our duty of care (also known as discharging our duty of care) and avoiding negligent action. The first is through engaging with relevant publications, such as many of the readings and resources referred to in this Study Guide. For example, child protection legislation, work health and safety (WHS) regulations, and codes of practice for organisations and particular professionals all provide guidance on what is expected of people in particular roles. By being familiar with the legislation in your state or territory, particularly regarding healthcare provision, WHS, and similar industry-related laws and regulations will help you develop your sense of what the community and legal standards are in the role of practice manager.

For example WHS laws, regulations, and codes of practice will be discussed shortly. Through exploring them, you will enhance your sense of what a practice manager needs to do in order to meet their responsibilities to their staff and clients. There are many resources that can be accessed in flashing out this information, such as the WHS guides that each state or territory government produces for work in different industries. A practice manager who insures that their practice operates in accordance with these guidelines would generally be considered to have met their duty of care in relation to the safety of staff, clients, and other visitors to the worksite. In contrast, a practice manager who fails to implement policies and processes in accordance with the WHS guidelines of their state or territory and relevant to their particular practice setting could be negligent.

The other source of information that can be used to guide determinations about what does or doesn’t meet duty of care responsibilities is a little more vague. It relates to industry standards and community expectations. For example, one factor courts use in determining whether a professional has been negligent or not is whether their behaviour accords with what is generally considered appropriate by professionals in the same industry. These can be clearly set out, such as in the codes of practice of a particular industry, but they are not necessarily as clear or detailed as the guidelines produced by regulatory bodies, such as the WHS guidelines we have already mentioned. These standards can often change – there are plenty of actions in response to child abuse or domestic and family violence (DFV), for example, that were common in the health services in previous decades but would be considered negligent today. As such, it will be important to regularly refresh your knowledge in this area regularly.

Work Health and Safety

Strongly related to duty of care is WHS. As you know WHS is a significant part of a practice manager’s responsibility. As such, while we address key points here, we know you are already very familiar with WHS from HLTWHS004 Manage Work Health and Safety, as well as other legal-, ethical-, and compliance-related units, and we will be moving relatively quickly through these concepts, knowing that you have those materials to refer back to if needed.

Originally, WHS regulations focused on physical safety – that is, identifying and managing risks to physical health – with organisations responsible for introducing and ensuring the application of practices to reduce injury risks associated with hazards such as lifting, carrying, and pushing objects; walking or climbing in potentially dangerous conditions; infection control; exposure to hazardous substances; and other hazards to physical health and functioning. (Remember, a hazard is something that could cause harm, while a risk is an assessment of the nature, potential severity, and likelihood of that harm.) All of these physical hazards remain critical concerns, of course, but we it is not recognised that we also face psychosocial risks at work, and that these are core concerns for WHS, too.

Psychosocial risks are things that could do psychological harm – such as leading to anxiety, burnout, or mental health disorders – or physical harm, such as raising the risk of cardiovascular or musculoskeletal disorders. Comcare (n.d.), Australia’s national WHS authority, identifies key psychosocial hazards including job demands, poor management, harassment, and exposure to traumatic experiences. This is a particular focus in the healthcare sector:

Widely acknowledged as the cost of caring, healthcare workers report higher rates of absences due to psychological distress and job burnout than workers in other sectors. Psychosocial hazards such as chronic exposure to occupational stress, place healthcare workers at greater risk of presenteeism (reduced productivity), anxiety and depression. Occupational stress relates to workplace interferences that can disturb a worker’s well-being physically and mentally, thereby fostering the potential for burnout. Moreover, the financial constraints of healthcare systems within developed countries are further pressurised by an ageing patient population, technological advances and poor worker retention. The Australian Institute of Health and Safety estimated in 2019, that worker’s absenteeism due to poor mental health, cost between $13 and $17 billion per year. These figures were exponentially compounded throughout the recent COVID-19 pandemic. For example, in a study conducted in England during the first wave of COVID-19, sickness absences due to poor mental health in National Health Service staff, increased from 519 807 days in March–April of 2019 to 899 730 days 12 months later.

The reduced productivity of healthcare professionals in the workplace can lead to suboptimal delivery of care to patients and therefore poorer treatment outcomes. Consequently, there is growing interest in boosting healthcare worker wellness, resiliency and self-care, globally. The framework for occupational health and safety is moving beyond traditional workplace hazards and now seeks to include emerging demographic factors such as mental health conditions. This view is reflected in the 2030 United Nations Goal that employment respects the ‘... physical and mental integrity of the worker in the exercise of his or her employment’. Additionally, in July 2022, Safe Work Australia released new codes of practice for managing psychosocial hazards at work, including risks to workers’ mental health. Using theoretical frameworks such as the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model or Watson’s Human Caring theory, researchers are developing support strategies that aim to improve well- being as well as understand worker’s wellness and exhaustion.

(Cohen et al., 2023, pp. 1-2)

WHS legislation (which refers to both WHS acts and associated regulations) are set out by each state or territory government, but most are largely similar, in accordance with SafeWork Australia’s model WHS laws. The acts are the overarching legislation that sets our legal responsibilities, which the regulations provide more information about how those with WHS responsibilities can go about meeting them. Perhaps the most user-friendly resources, however, are WHS codes of practice. If you don’t already have a copy, you should download How to Manage Work Health and Safety Risks: Code of Practice (SafeWork Australia, 2018) for a very practical guide to risk management in WHS. You should also search online for codes of practice or other guidelines published by your state or territory government. For example, a practice manager in Queensland should be guided by:

- Meeting your responsibilities under the state’s/territory’s WHS legislation.

- Information about managing WHS risks in relation to particular types of service delivery. For example, if the practice has practitioners who do or may undertake work in client homes, the practice manager must ensure there are policies, procedures, and resources in place to meet the responsibilities set out in Workplace Health and Safety Queensland’s A Guide to Working Safely in People’s Homes (WHSQ, 2018).

- Information addressing particular types of risk. For example, the more recent recognition of psychosocial risks has lead the Queensland Government to produce Managing the Risk of Psychosocial Hazards at Work: Code of Practice (WHSQ, 2022) to help address these risks. To support managers in facilitating the changes needed to accord with this code, they have also produced a Communications Kit.

Remember that codes of practice and other guidelines are regularly updated, so you need to access the most up-to-date version of any code you are using.

Self-Reflection

What physical hazards are you or your staff likely to encounter within an allied health setting? What psychosocial hazards are you or your staff likely to encounter? Do you think that health practices may face a higher level of psychosocial risk than other professional services? Why or why not? What are some key responsibilities of management in relation to these risks?

WHS and Policy Development

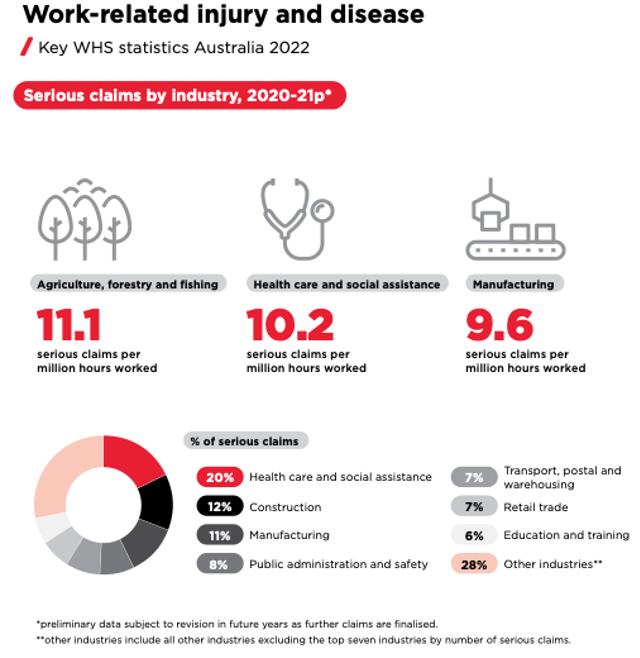

One of the reasons that WHS is so important to policy development in allied health practice is that health and social care services are among the leading contributors to the serious claims of work-related injury in Australia (SafeWork Australia, 2023, p. 12; see the image on the previous page). In addition to harm to staff, of course, there are many people who attend allied health practices, including clients and their family members, many of whom are particularly vulnerable. So, creating practice spaces and processes that meet safety standards is one essential priority for policy development.

- The ways hazards can be identified, including regular methods that managers undertake as well as other methods that may be required in particular circumstances and how hazards identified in an ad hoc manner (e.g., as staff go about their work) are reported.

- Risk assessment and control processes associated with all identified hazards.

- Establishment and maintenance of safe work processes, including education of staff as to appropriate and inappropriate actions in their specific area of work. For example, staff undertaking client care tasks face many similar but also some different risks to those undertaking administrative tasks, so the WHS guidance to each group must be appropriately tailored.

Find out more

As a practice manager, you will be one of the people with primary responsibility for these policies and associated processes. To refresh your memory from HLTWHS004 Manage Work Health and Safety, you may like to review SafeWork Australia’s (2018) How to Manage Work Health and Safety Risks: Code of Practice.

In creating policies to address WHS risks, the ideal is to remove the risk entirely, but this often isn’t possible. For example, there is no policy that can stop a worker being abused by a client or that can make effectively remove everything that could cause a physical injury in a workplace. What we need to do, however, is to adequately identify hazards and assess risk levels in relation to each identified hazard, then institute policies, procedures, and work practices that minimise risks to staff, clients, and other relevant people. That is, we need to apply the risk management process you are already familiar with to both physical and psychosocial risks (Work Health and Safety Queensland, 2022, p. 14; see image right).

Reading B

These extracts from the WHSQ Code of Practice for managing psychosocial risks takes you through the key responsibilities that need to be addressed in policies and procedures for addressing these risks. As you work through the reading, consider how you will make each responsibility clear in the policies you develop, including who holds particular responsibilities and what actions they need to take in order to meet those responsibilities. (And, of course, you can read the whole document. It is freely available here.)

WHS policies and procedures also need to consider:

- Who all the stakeholders are and how they will be consulted and involved in the review and development of policies, procedures, and work practices.

- How barriers to reporting hazards will be encouraged, who has responsibility for communicating identified hazards to management, and how management must respond to identified hazards.

- Processes for documentation of all WHS-related matters, including the risk management processed outlined above, as well as WHS incidents and follow-up actions, and consequences for staff (including managers) who do not meet their WHS responsibilities.

Rights and Responsibilities in Allied Health

Human Rights and Healthcare Rights

As you know, human rights are those things we are all entitled to as human beings, including the right to health and to receive health services that meet our needs.

Human rights recognise the inherent value of each person, regardless of background, where we live, what we look like, what we think or what we believe. They are based on principles of dignity, equality and mutual respect, which are shared across cultures, religions and philosophies. They are about being treated fairly, treating others fairly and having the ability to make genuine choices in our daily lives.

Respect for human rights is the cornerstone of strong communities in which everyone can make a contribution and feel included. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted by the United Nations on 10 December 1948, sets out the basic rights and freedoms that apply to all people. Drafted in the aftermath of World War Two, it has become a foundation document that has inspired many legally-binding international human rights laws.

The Australian Government has agreed to uphold and respect many of these human rights treaties including the:

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women

- Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

- Convention on the Rights of the Child

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

(Australian Human Rights Commission [AHRC], n.d.)

Find out more

You can find out more about human rights in Australia by following the links in the extract above. You can also find out more about the rights of Indigenous people, women, children, older people, people with disabilities, and LGBTQIA+ people here.

Healthcare Rights

Let’s look in a little more detail at healthcare-related rights. There is a set of rights agreed by state and territory governments across the country and which apply to every person receiving healthcare, stating that each of us has the right (see next page).

Reading C

Of course, knowing what your clients’ or patients’ rights are is only part of the picture – you also need to know how to uphold these rights in your practice’s operations. As you build this understanding, you will also improve your capacity to develop policy statements regarding these rights and procedures to guide actions to uphold them. Your next reading provides steps you can take to do exactly this.

Access

- Healthcare services and treatment that meets my needs

Safety

- Receive safe and high quality health care that meets national standards

- Be cared for in an environment that is safe and makes me feel safe

Respect

- Be treated as an individual, and with dignity and respect

- Have my culture, identity, beliefs and choices recognised and respected

Partnership

- Ask questions and be involved in open and honest communication

- Make decisions with my healthcare provider, to the extent that I choose and am able to

- Include the people that I want in planning and decision-making

Information

- Clear information about my condition, the possible benefits and risks of different tests and treatments, so I can give my informed consent

- Receive information about services, waiting times and costs

- Be given assistance, when I need it, to help me to understand and use health information

- Be told if something has gone wrong during my health care, how it happened, how it may affect me and what is being done to make care safe

Privacy

- Have my personal privacy respected

- Have information about me and my health kept secure and confidential

Give feedback

- Provide feedback or make a complaint without it affecting the way that I am treated

- Have my concerns addressed in a transparent and timely way

- Share my experience and participate to improve the quality of care and health services

(ACSQHC, n.d.)

Other Rights and Responsibilities

We have already covered several key responsibilities of workers within healthcare settings in general, and of practice managers in particular, through our discussions of WHS, confidentiality, and human and healthcare rights. But what other responsibilities do you and other workers have? And what rights do you and other staff have?

As a practice manager, you will have many responsibilities relating to administration; oversight, supervision, and governance; financial management; communications; and more. Many of those responsibilities will be mentioned in the examples in case studies and policy templates we explore throughout this unit. The clinicians and administration work workers within your practice will also have responsibilities that are specific to their roles. Allied health practitioners, of course, have many responsibilities relating to the provision of ethical and effective healthcare services and these clinical responsibilities are very different from those of other workers within the organisation. However, there are client rights and worker responsibilities that apply across the board.

For example, as you already know, clients of allied health services have rights to privacy and confidentiality. This means that they should be provided with treatment in private settings, unless there are group programs or spaces to which they have consented; it also means that information about the client which includes everything from their name, phone number, and date of birth to the details of the issues they are experiencing and the treatments they are receiving is considered private, and that it is the clients right to decide who has this information. As such, excepting in very specific circumstances, it is not allowed for any worker to share this information without the client’s consent, whatever the worker’s role. However, if the client or another relevant person is in a situation of significant risk if emergency services need to be called or if the clients records are subpoenaed for legal processes, the client may not have the right to determine whether information is shared for this specific purpose.

You may have noticed that the client right to privacy and confidentiality goes together with the workers’ responsibility to protect privacy and confidentiality. Similarly, the client or site visitor right to enter a safe treatment space goes hand-in-hand with every workers; responsibility to operate in accordance with WHS requirements. Similarly, practice management hold all the same responsibilities in this area as other workers, but also has the responsibility to ensure policies and work processes are in place – and are followed! – such that the workplace is a safe space for themselves, other workers, clients, and site visitors to enter and either conduct or receive services within.

In the healthcare industry, we most often focus on the rights of clients or patients and the responsibilities of healthcare providers or other workers within a practice setting. However, there are situations in which the rights of clients/patients and of workers are the same. For example, everyone has the right to be treated with respect and to be free from abuse within the healthcare setting. This right applies equally to every person involved with the service regardless of their role within the environment.

There are also some rights of workers that it is the responsibility of management to uphold. These include setting up structures for safe and effective work provision reducing risks associated with physical and psychological injury, providing the resources required to do the work and maintaining employment provisions, such as pay that accord with industrial relations law within Australia. Similarly, employing organisations need to work in accordance with anti-discrimination law (you can find a quick guide to that here) and avoid discrimination in their hiring and treatment of staff, as well as in their behaviour towards clients/patients.

Another useful source of information on the legal and ethical considerations we need to take into account when developing and implementing policies are the codes of practice of the various health professions. We have already introduced codes of practice for WHS, but the particular allied health professions within your practice will all have their own codes of practice, too. Many of these are similar because they tend to relate to core underlying principles. For example, health professions have core values and rights they recognise, which we have already discussed, while the helping professions (some of which are also allied health professions) have core values, which overlap with healthcare values:

- Autonomy refers to the promotion of self-determination, or the freedom of clients to be self-governing within their social and cultural framework. Respect for autonomy entails acknowledging the right of others to choose and act in accordance with their wishes and values, and the professional behaves in a way that enables this right of another person. Practitioners strive to decrease client dependency and foster client empowerment.

- Nonmaleficence means avoiding doing harm, which includes refraining from actions that risk hurting clients. Professionals have a responsibility to minimize risks for exploitation and practices that cause harm or have the potential to result in harm.

- Beneficence refers to doing good for others and to promoting the well-being of clients. Beneficence also includes concern for the welfare of society and doing good for society. Beneficence implies being proactive and preventing harm when possible (Forester-Miller & Davis, 2016). Whatever practitioners do can be judged against this criterion.

- Justice means to be fair by giving equally to others and to treat others justly. Practitioners have a responsibility to provide appropriate services to all clients and to treat clients fairly. Everyone, regardless of age, sex, race, ethnicity, disability, socioeconomic status, cultural background, religion, or sexual orientation, is entitled to equal access to mental health services. An example might be a worker making a home visit to a parent who cannot come to the a service because of a lack of transportation, child care matters, or poverty.

- Fidelity means that professionals make realistic commitments and do their best to keep these promises. This entails fulfilling one’s responsibilities of trust in a relationship.

- Veracity means truthfulness, which involves the practitioner’s obligation to deal honestly with clients. Unless practitioners are truthful with their clients, the trust required to form a good working relationship will not develop. Veracity encompasses being truthful in all of our interactions, not just with our clients but also with our colleagues (Kaplan et al., 2017).

(Adapted from Corey et al., 2023, pp. 18-20)

This means that any good code of practice for an allied health professional, regardless of their specific profession, will require that they uphold key client rights in relation to these principles. These codes of practice are not legally binding, but a good code of practice or code of ethics will be developed in consultation with legal and professional standards and breaching them can result in professional sanctions. However, codes of practice do not cover all the ethical or professional issues that can arise in allied health practice, and they tend not to provide practical steps to take in order to meet all their standards; rather, their guidance is more general and focused at setting out standards that promote ethical practice. As such, they need to be read and applied in concert with legal, ethical, and professional knowledge and standards of good practice. Organisations can support their staff in meeting the standards set out in codes of practice by ensuring that their policies and, in particular, the procedures set out to guide staff action are consistent with the relevant codes of practice: Because procedures outline practical steps to achieve policy aims, where policies are aligned with codes of practice, following the associated procedures should mean that staff act in accordance with these codes.

Rights and Policy Development

The rights and associated responsibilities we have been discussing are core concerns for us in this unit because they are some of the most important areas to address in policy development. We need to make sure that our policies:

- Make clear statements about these rights and responsibilities.

- Provide clear guidance (through procedures and other resources) for staff and managers in upholding these rights and meeting other responsibilities.

- Are enforced, with failure to act in accordance with policies identified and addressed with reasonable grievance or performance management and professional discipline processes.

In this section, we have developed a basis of legal, ethical, and other professional considerations for the development of workplace policies, as well as getting a sense of the overall development process. Before we go on, it will be useful to consider some recent and ongoing changes in the area of policy development; these will no doubt influence the policies of your practice and will be interesting areas for you to keep an eye on.

We have already noted several trends in workplace policy development in general and in the health sector in particular. For example, we have discussed the integration of psychosocial risk management into WHS policies. We have also seen the codification of healthcare rights. An area related to this, and one we will look at later in this unit, is the increasing recognition of the need to make healthcare services more inclusive and accessible, particularly for marginalised groups. Many resources to support work in these areas are provided by state and territory governments, so it is worth searching for them with key terms (e.g., “cultural safety”) and your state or territory – you will probably find plenty of quality resources to support your policy development initiatives.

In fact, the very fact of the importance of allied health and associated increase in government focus on it is relevant to policy development.

Allied health, as a collective of disciplines and professions, has historically not been well defined either nationally or internationally. This had led policymakers and governments to consider access to allied health care as supplementary and not a foundational right. Increasingly, governments are recognising that allied health plays a vital role across functions and sectors in supporting the health and social and emotional wellbeing of all Australians and is vital to the long-term sustainability of the health care system.

(Indigenous Allied Health Australian [IAHA], n.d.)

Now that there is a greater government focus, for example, there is increased government funding and guidance for allied health provision, as well as potentially increased oversight by governments through regulation and accreditation processes. Becoming familiar with these processes and requirements, then developing policy initiatives consistent with them, will be essential in your role as practice manager.

Particular principles and practices, as well as techniques and formats for policies and related processes, will be covered as we discuss the stages of policy development that they are particularly relevant to. So, as you progress through the unit, you will notice that there are many more key terms and concepts that arise. But we have enough of an introduction now to the core responsibilities and considerations for policy development that we can get into the process itself, which is where we turn our attention next.

In this section of the study guide, you learned about organisational policies and procedures, including policy development and implementation, as well as organisational, professional, legal and ethical considerations that need to be considered when planning, developing, and implementing policy.

- Allied Health Support. (2023). The how-to of policies and procedures. https://www.alliedhealthsupport.com/the-how-to-of-policies-procedures/

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2023). Action 1.07: Policies and procedures. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs-standards/clinical-governance-standard/patient-safety-and-quality-systems/action-107

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (n.d.). Australian charter of healthcare rights. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-06/Charter%20of%20Healthcare%20Rights%20A4%20poster%20ACCESSIBLE%20pdf.pdf

- Australian Human Rights Commission. (n.d.). What are human rights? https://humanrights.gov.au/about/what-are-human-rights

- Cohen, C., Pignata, S., Bezak, E., Tie, M. & Childs, J. (2023). Workplace interventions to improve well-being and reduce burnout for nurses, physicians and allied healthcare professionals: A systematic review. BMJ Open, 13, e071203. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-071203

- Comcare. (n.d.). Psychosocial hazards. https://www.comcare.gov.au/safe-healthy-work/prevent-harm/psychosocial-hazards

- Corey, G., Corey, M. S., & Corey, C. (2023). Issues and ethics in the helping professions (11th ed.). Cengage.

- Indigenous Allied Health Australia. (n.d.). Policy position statement: A rights approach to allied health. https://iaha.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/A-Rights-Approach-to-Allied-Health-Position-Statement.pdf

- NSW Government. (n.d.) Workplace policies and procedures checklist. https://www.industrialrelations.nsw.gov.au/employers/nsw-employer-best-practice/workplace-policies-and-procedures-checklist/

- O’Donnell, J., & Vogenberg, F. R. (2012). Policies and procedures: Enhancing pharmacy practice and limiting risk. Health Care and Law, 37(6), 341-344.

- SafeWork Australia. (2018). How to manage work health and safety risks: Code of practice. https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1901/code_of_practice_-_how_to_manage_work_health_and_safety_risks_1.pdf

- SafeWork Australia. (2023). Key findings. https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-01/key_whs_stats_2022_17jan2023.pdf

- Tarode, S., & Shrivastava, S. (2022). A framework for stakeholder management ecosystem. American Journal of Business, 37(2), 76-88. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJB-01-2020-0003

- Work Health and Safety Queensland. (2022). Managing the risk of psychosocial hazards at work: Code of practice. https://www.worksafe.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0025/104857/managing-the-risk-of-psychosocial-hazards-at-work-code-of-practice.pdf