In this topic, we focus on barriers which can impact client adherence and motivation along with strategies to overcome these and support the client in their health and fitness journey. You will learn:

- Human behaviour change

- The Stages of Change Model

- Requirements for successful behaviour change

- Factors which affect exercise adherence

- Instructor actions to enhance exercise adherence.

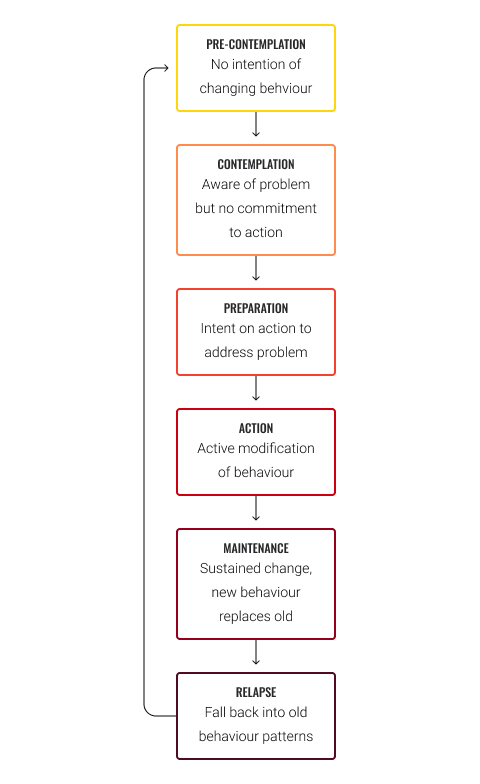

When considering how to motivate clients and support them in forming healthier habits, we first need to look further into human behaviour, in particular, the Stages of Change Model. This model, developed in 1986 by Prochaska and DiClemente, was developed in regard to smokers and studying how they were able to give up their habit or addiction. Since then, this model has been applied to a broad range of behaviours including, weight loss, injury prevention and a range of other addictions. In the world of health and fitness, the stage of change model is widely used to be better able to understand where individuals (clients) are in their process of adopting new habits and maintaining their new decisions. Becoming familiar with this tool will pay dividends in client adherence, motivation, and retention.

Before we begin, it is important to recognise that a change in behaviour does not happen in one step, this is not an overnight process. People tend to progress through different stages at their own rate, it is the role of the exercise professional to recognise which stage of change a client may be in and support them to progress through the stages at an appropriate rate for each individual, championing, not pushing, them on their journey to successful changes.

Let us look at the stages of change model in more depth in order to ensure we are fully equipped to support each client in their journey of habit changing.

Within Prochaska and DiClemente’s Stages of Change Model (also known as the Transtheoretical model), there are six stages, each with their own principles and processes to support change. It is important to note that whilst the time an individual may spend in each stage is variable, the steps to move onto the next stage are not. Certain tasks and principles of change which are designed to reduce resistance, encourage, and support progress and avoid reverting to old habits are better suited in some stages than others. Such principles include aspects of decision making and self- efficacy, the ability of an individual to execute the behaviours required for, in this instance, habit changing. Click on each of the six stages of change to learn more about their characteristics and the role of the exercise professional.

As the prefix of ‘pre~’ implies, an individual in this stage is not yet thinking seriously about making any changes and is also likely not looking for any help in this area. Characteristically, individuals in this stage tend to be defensive about their habit/ issue and feel it is not currently a problem. In other areas of addiction, this stage is also referred to as ‘denial’. Typically, someone in this stage would not be considering making changes within the next six months.

Your goal as the exercise professional is to:

- Help client develop a reason for changing

- Validate the client’s experience

- Encourage further self-exploration

- Leave the door open for future conversations ‘plant the seed’.

An individual within this stage is more aware of the personal consequences of the habit/ issue in question. They typically spend time thinking about their problem, but they are unable to consider the possibility of changing, often ambivalent about it. Although they think about the negative aspects of their bad habit and the positives of giving it up (or reducing), they may doubt that the long-term benefits associated with quitting will outweigh the short-term costs.

An individual could be in this stage for weeks or even years, the difference between those in the contemplation phase versus their counterparts in pre-contemplation is they are aware of the issue at hand, are thinking about it, and are open to receiving information about the issue.

Your goal as the exercise professional is to:

- Validate the client’s experience

- Clarify the client’s perceptions of the pros and cons of attempted weight-loss

- Encourage further self-exploration

- Leave the door open for moving to preparation.

An individual in this stage has made a commitment to make a change. This could present in the form of doing research, investigating what they would need to do to change their current behaviour (like beginning a personal training venture). An individual could spend weeks or months in this stage; often, however, people skip this stage, moving directly from contemplation into action and fail because they haven’t adequately researched or accepted what it is going to take to make a major lifestyle change.

Your goal as the exercise professional is to:

- Praise the decision to change behaviour

- Prioritise behaviour change opportunities

- Identify and assist in problem solving re: obstacles

- Encourage small initial steps

- Encourage identification of social supports.

Individuals in this stage believe they can change their behaviour and are actively taking steps to do so. They review their commitment to themselves and develop plans to deal with pressures that may lead to slips. They may use short-term rewards to sustain their motivation and analyse their behaviour change efforts in a way that enhances their self-confidence. They are making over efforts to quit or change their behaviour; however, they are at the greatest risk of relapse. A key difference in behaviours of those in this stage is that they tend to be open to receiving help and are also likely to actively seek out help and advice from others. Individuals typically remain in this stage for 3-6 months.

Your goal as the exercise professional is to:

- Guide/help implement action towards the goal

- Provide encouragement and motivation

- Identify and assist in problem solving – remind the client of their end goals

- Acknowledge successes

- Monitor progress.

Individuals in this stage have adopted new behaviours and are aiming to maintain these as the new status quo. As a result of effective planning, research and gathering of advice in the earlier stages, these individuals can typically anticipate the situations in which a relapse could occur and prepare coping strategies in advance. They remain aware that what they are striving for is personally worthwhile and meaningful and are patient with themselves, recognising that it often takes a while to let go of old behavioural patterns and practice new ones until they are second nature. Even though they may have thoughts of returning to their old bad habits, they resist the temptation and stay on track. Individuals typically remain in this stage post six months to five years.

Your goal as the exercise professional is to:

- Encourage adherence to program

- Monitor progress.

Transcendence

The stage of transcendence was added to the Stages of Change Model by other researchers who maintain that:

This is the stage of ‘transcendence’ into a new life. If a person ‘maintains maintenance’ long enough, they reach a point where they can work with their emotions and understand their behaviour and view it in a new light. Not only is the bad habit no longer an integral part of their life, but it would seem abnormal, even weird, to return to it.

It is important to note, the journey to change presents with obstacles which are tricky even scary for individuals to overcome, change is not easy. Along the way, even the most dedicated individual may experience a relapse. It is common to have at least one relapse, often accompanied by feelings of disappointment and failure. While relapse can be discouraging, it is important to note that the journey to change is not a straight path from old habits to new habits. Instead, due to life, behaviours, thought patterns and other factors, individuals will more naturally cycle between the five stages several times before achieving a successful and stable lifestyle change, relapse within the stage of change model is considered normal.

The following video provides an overview of the Stages of Change Model, what the video and consider how this could be used with clients.

Sometimes letting things go is an act of far greater power than defending or hanging on.Eckhart Tolle

It is important to emphasise that the process of changing behaviour is not a simple one. Most people have difficulties giving up things they enjoy or have become accustomed to, they may not be in control of their behaviours or society may not support a healthier lifestyle. This is the challenge of behaviour change: providing the right framework - mental, physical, or social - in which an individual can change. How can exercise professionals, help clients to succeed in changing their behaviour? Three major components of successful behaviour change are:

- Skills

- Knowledge

- Desires.

Let us take a look at each of these in more detail.

Skills

Skills required to adopt a change arise in several areas, these typically include:

- Planning skills

- Time management skills

- Cooking

- Training

- Analysis and self-management.

Planning skills

For behavioural change to be successful it must be on-going, the best way to achieve this is to have a plan to follow. Strategies for success include:

Effective goal setting can help clients plan for change - clients need practice in setting realistic and specific goals that, when possible, are measurable.

Long-term goals should be divided into short-term goals - clients should focus on behaviours they can change rather than outcomes that may be outside their control. The role of the exercise professional is to make their goals smarter (cheat: create a goal-specific to showing up to exercise). An example of goals could be:

- Exercise adherence: to attend and fully participate in 95% of scheduled training sessions over 6 months

- Healthy eating: to limit takeaway/bought food meals to once a week

- Combined goal: to lose 5kg in three months.

Time management skills

One of the biggest “excuses” given for non-compliance to exercise and healthy nutritional practices is a lack of time. The key is to assist clients by encouraging the idea that exercise is a priority. This can be achieved with a plan, and make exercise a part of the clients daily schedule. A plan needs to be flexible, and not too restrictive to ensure they adhere to their exercise routine and not neglect it.

Time management and nutrition skills

Preparation is the key to healthy eating – meal planning! A lack of time management skills results in people being rushed into food choices and getting whatever is quick and easy (usually poor quality food). Having good time management skills for nutrition can look like:

- Getting up a fraction earlier to make lunch

- Making an extra portion of dinner to eat for lunch the next day

- Bulk meal preparation & freezing portions.

Cooking skills

Many people do not have sufficient skills in the kitchen to make nutritious meals. Instead, they rely on pre-packaged, microwavable meals, fast food, and junk food. Learning to cook can be as simple as:

- Watching TV

- YouTube

- Following a recipe

- Social media

- Cooking for dummies sites

- Asking friends and family.

- There is no excuse for not being able to cook.

Training skills

To change a behaviour, you must be open to learning new skills. Training can be as simple as:

- Reading books

- Searching the internet

- Online courses

- Learning from others

- Attend night classes in subjects like time management goal setting, nutrition, cooking, anatomy & physiology, or personal training, for example.

Analysis and self-management skills

“Self-management” is an essential skill for increasing self-awareness. Clients can practice keeping records of their own behaviours, their successes and failures – this also keeps them accountable. Believing that one can make the change is the first critical step to behavioural change. The role of the exercise professional is to advise the client on the skills required and give direction on options for developing these skills.

Exercise skills

Initially the exercise professional may play a facilitating role in the exercise program but must encourage client input every step of the way, providing help through the planning process, goal-setting and early re-evaluation stages. It is important to encourage the client to take control of the programme monitoring, this can be achieved by having the client record the data and analyse their performances. As the exercise professional, you must maintain an active interest in their progress to ensure motivation.

Relapse prevention skills

Educating clients on how to deal with relapses is critical. Emotional distress is a primary factor in lapses and relapses. Emotional distress refers to the victim's emotional response to the accident and/or injuries, such as fear, sadness, anxiety, depression, or grief. Several emotional, mental, and psychological damages can fall under the category of emotional distress during an injury claim.

Learning stress management skills is essential in order to cope effectively with stress. These skills are invaluable for the individual trying to effect a major change in behaviour, which is a major stressor in itself. Exercise professionals can introduce relaxation techniques such as meditation, yoga, massage, deep breathing, positive self-talk, and imagery among other skills to reduce stress and help client’s deal with disruptions and setbacks. It is important to note that stress management skills may minimise counterproductive negative emotions.

Assertiveness skills

Developing “assertiveness skills” can be helpful in a number of ways. Assertiveness may help a client refuse peer demands such as having a drink, eating low-quality food, and smoking for example. Developing and or fine-tuning skills in assertiveness may help individuals to ask others for feedback about unhealthy habits and guidance in making changes. As individuals become more aware of their strengths, weaknesses and needs they can be assertive in recruiting others’ support for our change efforts.

Other important skills

Other relevant skills worth developing relate to risk assessment and assertiveness.

Risk assessment

When planning to change behaviour, it is important to practice recognising high-risk situations for a lapse or relapse and figure out coping skills for those situations. It is recommended to identify times and opportunities for setbacks in order to develop plans to effectively respond to a relapse. Mental imagery to help picture one’s self in the future with healthier habits may help maintain the hope needed to get back on track and continue to pursue change.

Let us combine this and expand the picture of the requirements for successful behaviour change.

- Skills

- Planning skills

- Time management skills

- Cooking

- Training

- Analysis and self-management

- Relapse prevention skills

- Assertiveness skills

- Other skills such as risk assessment.

- Knowledge

- Desires

Let us now consider the knowledge required for effective behaviour change.

Knowledge

The second prerequisite for successful behaviour change is knowledge, this should come in the form of:

- Exercise and nutrition knowledge

- Knowledge of personal behaviours

Exercise and nutrition knowledge

Despite all the information out there, people typically still have limited knowledge about nutrition and exercise. Many people do not do weekly food shopping or know how to read and compare nutritional labels and products. They may also ‘believe’ they already know what is and is not good for them based on hearsay, for example, how many people do you know who still think carbs are bad, fat is bad, sugar…..bad? In relation to exercise, many think simple moving around from A to B is sufficient in terms of volume and level of exercise.

This is where the exercise professional comes in, equipped with advice and knowledge to provide clients with the tools required for gathering knowledge in the areas of exercise and nutrition. This could range from, for example, sharing simple tips (avoiding getting overly technical or scientific) advising such as eating less take-aways, providing guidance to simple nutritional swaps, aiming for a 10,000-step goal. Sharing knowledge may extend from simple tips to more in-depth information gathering, pointing clients in the direction of useful sources of information (websites, newspaper articles and reliable TV programmes).

Knowledge of personal behaviours

A lot of people do not realise the extent of damage they are doing to their bodies through unhealthy behaviour until it is too late. Therefore, the role of the exercise professional is to guide (not push) the client in the right direction, allowing them to digest information at their own pace. With this approach, there is a greater likelihood that the client will better see the danger of their current unhealthy behaviours should they continue. This could take the form of documentaries or articles which show the effects of continued poor nutritional practices and lack of exercise may be enough to get them thinking about a change for the better.

The approach taken should take into consideration the stage of change the client is currently in. For example, for those in the pre-contemplation stage, not yet considering implementing any changes, may need a gentle illustration of how certain behaviours would benefit from some attention. Some strategies could be:

Write them down

Having the person write down and analyse their behaviour is a good technique to show people how bad things really are. For example, many people after completing a 4-day dietary intake survey, realise how bad their diet actually is!

Have a look at other people’s behaviour

Comparing their behaviour to the recommended norms will give them a clear idea of where they are at (i.e. exercise levels, Kcal intake, alcohol intake etc).

Desires

Your desire to change must be greater than your desire to stay the same.Charles E Hudson

Probably the most important of the requirements for behaviour change. To change any behaviour for the better, a person must actually want to! Click on each of the following desires to learn more

When a client wants to make a change, they are no longer in the pre-contemplation stage. They have begun to think about their current behaviour, likely started researching information in relation to becoming healthier and possibly even begun to formulate a plan. For many, this will be as far as they get.

After making the decision to make a change, each individual must then go through a process of weighing up the pros and cons of this behaviour change. Many people will do this and realise that they should change, but they lack the want to change, or think that the process of change will require too much hard work on their behalf.

People may do all the research, get all the help they need, go as far as planning the action phase, making the appointments and in some cases even starting the action phase…yet still lack the desire to go through with it.

How many of you know people that have paid for a gym membership then rarely used it? There will be a very small number of you that begin this course and decide not to continue…you soon realise… paying the money is the easy part!

It is important to recognise the early signs of low motivation:

- Negative self-talk

- Lack of interest

- Not showing up

Nip these in the bud, get to the root of the issue – remember their pain. Recognise the stage of behavioural change the person and begin to consider appropriate strategies.

Some people have difficulty letting others in, others are reluctant to ask and some do not know where to start when seeking support, unaware that there are alternative options available. For example, many people find the idea of entering a gym daunting. It would be ideal to get to the root of this, why do they find it nerve-wracking? Is it the clothing, the equipment, the people or a mixture of these and other reasons? some people may assume the gym is the only place to go to exercise, not realising that there are many options available that can get the same results or perhaps better than a gym-based program. The best thing to do is to offer information or guidance of the variety of professionals, organisations and programmes that are already around to help with the behavioural change process, enabling and allowing the person to make the choice that is right for them.

As many as 80% of people who begin an exercise program do not stick with it. While initially, many people are motivated to begin an exercise program.Association for Applied Sport Psychology

One of the most effective motivators to doing and maintaining something is enjoying it. Whilst it can be said that everyone who begins a new exercise routine has done so as they are wishing to make healthy habit changes, with the best of intentions, life, however, can throw curveballs which the client may need some advice as to how to overcome or incorporate these into their life, balancing their training. Factors which may affect exercise adherence can be broken up into three main categories:

- Personal factors

- Environmental factors

- Cognitive (psychological) factors.

Let us look a little deeper into each of these.

Personal factors

The following have been identified as possible factors affecting exercise adherence:

- Smoking

- Age

- Income

- Weight loss diets

- Level of education

- Weight

- Personality type

- Gender

- Exercise/sporting history

Let us take a closer look into the reasoning behind how these possible factors contribute to exercise adherence.

Smoking – Oldridge (1983) found that smokers were 2.46 times more likely to drop out of an exercise program (than non-smokers). During exercise blood flow helps boost oxygen supply to your muscles. The physical effects of smoking include the nicotine and carbon monoxide from smoking making the blood thicker and narrowing the arteries. Narrow arteries, in turn, reduce the flow of blood to the heart, muscles and other organs, making exercise harder. Adverse effects smoking has on health and aerobic capacity may also mean the smoker is starting from a more de-conditioned physical state and therefore finds the exercise very uncomfortable (breathlessness etc).

Age - there is no question that “involvement” in regular exercise generally decreases with age. However, some research suggests that once a regular exercise program has been established, the elderly may be more likely to adhere. Ward & Morgan (1984) along with Gale et al (1984) found that program adherents tended to be older than dropouts.

Income - ACSM Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription (Ed 6) state that blue collar employment, along with an inactive job, smoking and inactive leisure time are the largest predictors of exercise non-compliance. Some individuals may not earn sufficient income to participate in regular exercise programs. Lifestyle changes (i.e. loss of a job, drop to one income when a baby is born etc.) may not allow a person to continue with a preferred mode of activity due to financial constraints. Due to income restrictions, choosing the exercise modes they enjoy may be impossible due to the inability to pay subscriptions/memberships. This may affect their levels of motivation and thus adherence to a program.

Weight loss diets - losing weight needs to be the result of a “lifestyle” change if it is to be successful long-term. Diets are essentially short-term in nature, consisting of calorie restriction plans that are almost impossible to maintain over time. This often results in weight gain once the target has been achieved and the “diet” has finished. Exercise adherence is a long-term “lifestyle” change. It is not about the next four weeks, but about the next four decades! Those who have attempted diets repeatedly may also take the same approach to exercise (meaning adherence is unlikely). For this reason, it is important to reset your exercise goals once the initial goal has been achieved (e.g. weight loss). Setting a short-term goal such as fitting your wedding dress is great motivation initially, but what happens after the wedding?

Level of education - while it may seem knowledge of the “benefits” of exercise would promote adherence, studies show information alone does not translate to adherence. Understanding the health benefits of exercise may lead to an intention to exercise, but taking action requires something more. Research has shown the higher the level of education, the greater the involvement in physical activity. But there is no hard evidence exists about adherence rates at this point. There is no clear relationship between what we know and what we do. Knowledge of the health benefits of exercise may motivate initial involvement, but feelings of enjoyment and well-being rate substantially higher in reasons for adherence.

Physical factors (e.g. Weight, illness, perceived fitness level etc.) - excess body weight and unhealthy composition, along with low fitness levels and injuries, have all been shown to have a negative effect on adherence to exercise programs. Someone who is slim, fit, and injury-free is more likely to adhere to an exercise program than the unfit, overweight, injury-prone individual.

Those with excess weight are unlikely to have had a high participation rate in exercise (in recent times at least). 70% of obese people will stop even a gentle walking program within a year (Dishman et al,1985). Overweight individuals were less likely to respond to alternative exercise programs (e.g. water-based, yoga etc) (Dishman et al,1985). This means they are likely to be unconditioned and may be more likely to suffer from ongoing conditions (e.g. diabetes, high BP) and medical complaints (joint pain, lower back pain). They may also suffer from low self-esteem/confidence based on their body image ….all excuses that may be used to stop a program.

People who perceive their health as being poor are unlikely to enter or adhere to an exercise program, and if they do they are likely to perform little exercise (Dishman et al,1985).

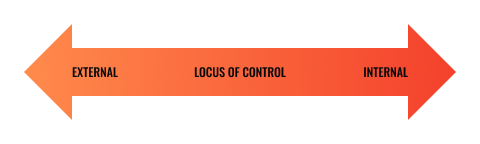

Personality type - Locus of Control is a psychological construct that refers to people’s belief about whether or not they are personally in control of what happens to them (Weinberg 1995). Essentially, it asks the following question, “do you believe that your destiny is controlled by yourself or by external forces (such as fate, god, or powerful others)?

The concept of Locus Control is initially used to distinguish between two types of situations:

- Those in which the outcomes are believed to be determined by skill or ability – Internal Locus of Control.

- Those where chance/luck is perceived to be the main determinant of success or failure – External Locus of Control.

Those who finish toward the External Locus of Control:

- Tend to attribute outcomes of events to external circumstances such as fate, luck, being unfair, or systems/processes etc.

- Are less likely to worry about their health (“not in my control”)

- Are more prone to anxiety and “learned helplessness”

- Are less willing to take risks or work on self-improvement.

None of these attributes bode well for sticking to an exercise program!

Those who finish toward the Internal Locus of Control:

- Tend to attribute outcomes of events to their own abilities and control, i.e. personal decisions and efforts

- Have high achievement motivation

- Are more likely to work for achievement

- Plan long term goal

- Are more likely to be aware of good health practices and implement them

- Are more likely to take preventative medicines, exercise regularly and quit smoking than individuals with external.

Gender - research conducted by Weinberg and Gould (2007) identified a decline in participation in regular activity among both boys and girls from approximately 70% participation at the age of 12, reaching as low as 30-40% by the age of 21. Weinberg and Gould (2007) also identified females and the elderly to have higher levels of inactivity than males or younger individuals.

There does not appear to be any significant difference in adherence rates between men and women, however, the major predictors for adherence are different, for example, social support seems to play a much larger role in women’s participation in exercise than men.

Exercise/sporting history - studies suggest that exercise habits in adulthood are often established in childhood. Exercise programs in schools can be effective in improving fitness levels and increasing participation in health-related activities in children. Students who participate in quality physical education programs can increase levels of fitness and gain the necessary knowledge and enjoyment levels essential to impact future patterns of adherence to exercise programs (Seefeldt, 1986). Unfortunately, however, most schools do not offer students enough contact hours in programs of quality, so the positive impact on future exercise behaviour does not occur.

Environmental factors

Along with considering an individual's personal factors which can impact exercise adherence, it is also important to be aware of possible environmental factors which can play a role in exercise adherence.

The following have been identified as possible factors:

- Group cohesion

- Social support

- Economic cost

- Disruptions

- Enjoyment of exercise

- Specific individualised feedback.

Let us look into each of these further.

Group cohesion - group camaraderie has been cited by numerous studies as a key factor in adherence, identifying that people prefer to exercise with another person, or in groups. Cohesion and friendship within a group is one of the strongest predictors of exercise adherence. Group cohesion can present as:

- friendships

- joining/going with friends

- carpooling and post-program socialising

Social support - social support includes the resources provided by:

- one's social network of family

- friends

- co-workers

- health professionals

- and community resources.

These networks may assist in behaviour change by providing appropriate information or encouraging the individual to participate in healthy behaviour. Receiving support from a person the individual relates directly also influences their persistence with the activity, for example, a husband, or friends asking a woman if she has lost weight or a girl asking a guy if he works out. This is recognition of the sweat and hard work the individual has put in.

A supportive partner, family member, or friend may offer to exercise along with the individual when they are feeling unmotivated, or they may find another means of helping them adhere to their regime such as minding their children, counting their sit-ups, driving them to their training when it rains. Positive family social support is thought to be one of the major determiners of exercise maintenance in women. A lack of support through negative or indifferent attitudes can have an adverse effect on adherence, even when the exercise program may be life-saving! It is been proven that those whose spouses were indifferent or negative about their exercise program were three times more likely to drop out. Findings have also shown that a lack of spousal support was the single most prominent factor that predicted non-compliance.

Heinzelman & Bagley (1970) in a study on exercising married males found that:

- Those participants with positive wives had an 80% adherence rate

- Those participants with negative wives had a 40% adherence rate

Some studies have even suggested that a spouse’s attitude could be even more important than the attitude of the participant.

Economic cost – the cost of regular physical activity could be prohibitive to some individuals. Also, the mode of exercise an individual is most enthusiastic about may be out of their price range (i.e. can’t afford a gym membership), so they must go to less enjoyable/preferred modes of activity.

Disruptions – even the most dedicated exerciser will get sick, injured, have unusual work commitments or family emergencies that result in a missed session or two. It is important to be aware that life instances such as relocation, medical problems and period travel can also, create new barriers to exercise participation and adherence.

Injuries are one of the most common reasons for disruptions to exercise participation. Newcomers to exercise who suffer injuries may become discouraged and return to their sedentary behaviour. In order to reduce the likelihood of injuries, the exercise professional should do everything in their power to ensure correct technique and environmental safety in order to avoid client injury.

Enjoyment/interest in exercise – attitude towards physical activity in general is an important factor in adherence. Some people hold negative feelings towards exercise, usually based on previous negative experiences. Where adherence is concerned, it is definitely advantageous to have an interest in a specific form of physical activity. Many of those who drop out feel that their training is boring, it is the role of the exercise professional to work with the individual to find a move of exercise they love.

In addition, with or without their training plans, participants move from equipment to equipment and crank out set after set without reason, and without knowing they are progressing, knowledge and client education is key, bring them along on their journey provision rational and explanation behind “why” they are doing what they are doing in order to support them in having both understanding and ownership in what they are doing.

Love what you do, do what you loveWanye W. Dyer

Specific individualised feedback - many facilities invest a large share of their energy and budget into attracting new customers via promotions such as "open house" campaigns, member referrals or 30-day trial offers. These types of promotions provide little benefit to existing members, resulting in too little attention on a regular basis which leads to a lack of personalised feedback. In short, little to no interaction with exercise leaders and can cause a decrease in motivation. Multiple studies have surmised that adherence rates were higher in participants who had ongoing individualised feedback.

Unsupervised programs are effective, but clients need:

- to know how to start

- to have early supervision

- access to discuss progress reports with an exercise professional.

Cognitive factors

Cognitive (physiological) factors can also impact exercise adherence in individuals. The following have been identified as examples of cognitive factors:

- Perceived lack of time

- Convenience

- Self-efficacy

- Self-motivation.

Let us look into each of these.

Perceived lack of time - due to long working hours, family, or other commitments, some individuals may find it difficult to work regular exercise into their daily schedules. Furthermore, in terms of prioritising an exercise regime, where an individual places exercise in terms of an order of importance will also play a role. For example, it may look like;

- Boyfriend/girlfriend

- Family

- Friends

- Work

- Social life

- Pet(s)

- TV

- Shopping

- Exercise.

Convenience - the convenience (or perceived convenience) of exercise facilities or opportunities to participate in may help determine a individuals’ persistence with exercise. The proximity of an exercise facility to an individual’s home is a major adherence factor.

Self-efficacy - this may well be the largest predictor of exercise adherence. The term “self-efficacy” refers to how well an individual feels they can carry out a task; if the individual feels that they can succeed in an exercise program, they are more likely to. The participating clients must believe that the prescribed fitness activities will produce the desired effects and that they have confidence in their ability to do as prescribed, this is achieved along with the exercise professional who provides education and knowledge behind the “why” of the program along with encouragement as they embark on a new regime/lifestyle modification.

Self-motivation - individuals who are highly self-motivated are inclined to adhere to a self-monitored exercise program longer than those who are not highly self-motivated. Self-motivation typically refers to the pressure an individual puts on themselves to perform at a high level, further motivations are typically subdivided into two different types of motivation.

- Intrinsic - motivation which comes from within the individual e.g., performing an activity without a focus on the outcome, simply for the enjoyment of taking part, personal satisfaction or accomplishment

- Extrinsic - motivation which comes from an external source e.g., pressured from others ( family, partner, friends), material rewards such as money or the thrill of performing in front of a large crowd, sponsor or knowing talent scout is present.

By having more intrinsic motivation the individual may freely engage in the activity and have a full sense of personal control.

Examples of motivating factors

There are different motivations depending on age. The top five motivating factors for people between the ages of 16 and 44 are:

- To feel in good physical shape

- To improve and maintain health

- To achieve mental alertness

- To have fun

- To get outdoors.

The top five motivating factors for people between the ages of 45 and 74 are:

- To achieve mental alertness

- To feel in good physical shape

- To get outdoors

- To feel independent

- To relax and forget careers.

As the exercise professional, it is important to think of a program from the client’s perspective, acknowledging that exercise is both voluntary and time-consuming. This means, it is important to be flexible in the approach to program design and consider as many of the factors which influence adherence as possible. By understanding the factors of exercise adherence and barriers to participation, the exercise professional can identify high-risk individuals and plan methods to help them stick with an exercise program.

The following information, adapted from ACSM guidelines, discusses a collection of various positive and negative variables which can impact a client’s adherence to their training program. Leaning more towards the positive side will result in increased adherence, conversely, leaning more towards the negative side will result in more ‘drop-outs’.

| Poor adherance (negative variables) | Good adherance (positive variables) |

|---|---|

| Inadequate leadership | Instruction and encouragement |

| Time inconvenience | Regular routine |

| Musculoskeletal problems | Freedom from injury |

| Exercise boredom | Enjoyment, fun and variety |

| Individual commitment | Group camaraderie |

| Lack of progress awareness | Progress testing and recording |

| Spouse and peer disapproval | Spouse and peer approval |

Practical recommendations for instructors

There are several ways in which the exercise professional can support their client to balance the obstacles which life can present. It is important to note that supporting the client is exactly that, it is not pressuring them into exercises, it is about establishing a pattern or routine which best supports their lifestyle and needs. Find a routine which they enjoy, feel comfortable with, feel is achievable and not too much of an additional activity they need to make time for are all key considerations when designing a new routine in which they are likely to adhere too. The following are some practical recommendations to guide the exercise professional in effectively supporting their clients.

- Positive reinforcement of desirable behaviours.

- Provision and encouragement of social interaction.

- Discussion of barriers and strategies to overcome them.

- Provision of specific individualised feedback.

- Prevention of disruptions to training.

- Improving enjoyment through tailoring of activities to client preferences.

Let us look further into each of these and discuss the role of both the client and the exercise professional.

Positive reinforcement of desirable behaviours

We often focus our energy into the clients that are at risk of dropping out or drop out back into training.

Do not forget the clients that are attending:

- Offer praise, support and encouragement as often as possible to those who are adhering

- Make contact with those clients you feel may be at risk of non-compliance

- Don’t forget about the existing clients - offer rewards for adherence, loyalty and effort

- Let your clients know you are keeping an eye on them and are there for them if needed.

ACSM suggests instructors provide positive reinforcement through periodic testing. This can be performed by doing initial tests such as:

- body fat percentage

- predicted VO2 max

- strength/endurance levels etc.

Re-testing at regular intervals, an instructor can positively reinforce the behaviour through results. Favourable changes to these measures can serve as powerful motivators that produce renewed interest and dedication.

Provision and encouragement of social interaction

The support of family, friends and co-workers should be sought from the beginning. Encouraging (or helping) them to find a compatible exercise partner often serves to enhance exercise adherence. Programs where people exercise alone compare poorly with those programs incorporating group dynamics in terms of adherence rates.

ACSM guidelines state that commitments made as part of a group tend to be stronger than those made independently. The social support provided by others may offer the incentive to continue even during periods of sagging interest.

Things we can do as a PT:

- Special rates for small groups or pairs

- Introduce clients to each other if you think it to be of mutual benefit

- Encourage clients to invite a friend or family member along to a session for free.

Family support

Ask clients about the level of support they are getting from their significant others regarding exercise. If a client is concerned that exercise takes time away from family, try to help them understand that exercise will help them be more relaxed and healthy and help them to enjoy their time with their family more. Better yet, have the family participate in the exercise! Studies show married couples that exercise together are more likely to stick with an exercise program (Young 2005). We can suggest fitness routines with children, such as jogging while children ride bikes. If they all have fun doing an activity, adherence is almost guaranteed!

Discussion of barriers and strategies to overcome these

It is important to discuss any actual (or potential) barriers to exercise before the program commences. A detailed screening and interview process should tell you what you need to know here – client interview.

Once the barriers have been brought out into the open, they can be discussed frankly, and strategies can be put in place to overcome them. Barriers could be complicated and resulting from medications or medical conditions, or simple, such as transport, busy work schedules, body size. The more of these barriers you can limit, the greater the chances of client adherence.

It is important to be flexible! Successful exercise professionals are problem solvers! It is essential to be prepared to work around the client’s schedules or work the exercise into the client’s daily activities – weekly plan. In order to best support the client, consider options such as taking the session to the client, researching any medical conditions which may be relevant to the client and adjust exercises to the appropriate level of the client whilst still achieving results.

ACSM Guidelines for common special populations barriers

Women, older adults and the obese are faced with several unique barriers to exercise participation, which may account for their lower initial enrolment, poorer attendance and higher drop-out rates. The following information provides insights to some of the common barriers and provides some solutions which can be implemented or modified in order to guide the client to succeed in their new journey. Click on each of the below to read more.

- The role of care-giver is typically the woman’s. Working around the needs of children and household duties is tough

- Some women are uncomfortable exercising in a male dominated environment.

- Poor health, pain, weakness

- Fear of Injury

- Lack of income to gain access to exercise facilities.

- Often the obese will have a negative perception of exercise due to past experiences (feel inadequate, limited physical skills)

- Access to machines, lack of comfort on cardio equipment

- Body image – they do not like busy environments because they feel they are being judged.

Provision of specific, individualised feedback

Research has shown that participants in exercise programs who felt they were not getting individualised attention from exercise program leaders were more likely to drop-out. This highlights the importance, need and desire of immediate, positive feedback on the reinforcement of health-related behaviours and this being well documented.

Regular re-testing of the client’s goals is of fundamental importance, along with incorporating personal goal setting, periodic testing, and progress charts to demonstrate and document exercise achievements in order to foster encouragement and adherence.

ACSM suggests introducing a progress chart that allows clients to document daily and cumulative exercise achievements (i.e. Km's cycled/run). This could either be used as a private source of motivation or if the client has no objections it could be strategically placed in the gym to be used as a motivator to all participants.

Preventing disruptions to training

If the potential barriers have been discussed with the client and strategies have been developed to overcome them, the occurrence of disruptions should not grind the exercise program to a complete stop. It is a good idea to put plans into place to support missed sessions, for example, if for some reason a client is unable to attend a session because of other commitments there should be a back-up plan. Sometimes, all the planning in the world is not going to help. A family event, holiday, or injury could throw out even the best plan.

- To minimise disruptions to training, it is important to reinforce that a short break in training is not the equivalent of failure

- Consider programming breaks for clients as ‘rest’ periods

- It is equally important that the instructor not be the cause of the disruption (i.e. injury, sickness, missed sessions, disengaged attitude).

Prevention is the best cure

- In the case where a client may suffer from a medical condition, be sure to encourage regular check-ups by their doctor

- For new exercisers, minimise the risk of injury and/or complications with a moderate start to exercise prescription

- Do not over prescribe.

Minimise the risk of injury

Quite often, novice exercisers become discouraged due to muscular soreness or injury from increasing the activity intensity too quickly. Excessive intensity, duration or frequency of exercise may offer the participant little additional gain in fitness, and substantially increase the risk of injury. Therefore, it is important to ensure that program design and client support is conducted with the FITT principles in mind. Ensure that perspective is maintained throughout, in the sense that it is important to remember the client is a different to yourself, other clients or other instructors, with plans and programs formulated based on the client’s goals, barriers and abilities, without comparison or judgement. When planning to minimise injury, always ensure:

- a proper warm-up is performed

- appropriate exercise attire is worn

- the environment is suitable for the session

- the client is monitored at all times during the session

- adequate hydration and rest are achieved and look for “danger signs”, chest pain, dizziness etc.

Relapse prevention training

Exercise professionals should prepare participants for situations that may produce a relapse, suggest ways of coping with them so that a complete relapse is avoided. Relapses should be viewed as inevitable challenges, rather than failures, for example, winter training drop-off, too cold to train excuses.

Improving enjoyment through tailing of activities to client preferences

Enjoyment of the exercise program will obviously have a positive effect on adherence, that is not to say the greatest benefits are achieved entirely through enjoyable actions (no pain no gain still has its place).

A key skill of a successful exercise professional is to listen to the client carefully, ignoring their wishes shows a lack of empathy and will most often result in a lack of……client! Involve the client in the decision-making process.

Every client will have their likes and dislikes, so it is important that extra thought goes into the planning and exercise selection process. One client may enjoy the endorphin rush of weight training, while another enjoys the meditative effects of yoga. Regular consultation with the client will enable the exercise professional to determine what aspects of the program the client likes and dislikes and strive towards maximum enjoyment and adherence. A perceived “lack of choice” in exercise type can lead to increased dropout rates.

Methods to increase enjoyment

Add variety - emphasise variety and enjoyment in the program.

Regularly change it up - change up the program regularly to not only challenge but also engage the client. Many activities can become monotonous and boring if left unchanged for too long, resulting in reduced exercise adherence.

Recreational games - ACSM suggests including an optional recreational game to the conditioning program format.

Introduce new tasks with a fun element - as enjoyment level increases so too does client motivation. Consider activities such as:

- boxing

- kick-boxing

- mini-circuit

- wobble board/swiss ball games etc.

Methods to increase adherence and support barriers or relapses

- Positive feedback

- Provision and encouragement of social interaction – group exercise, group PT

- Discussing barriers and strategies to overcome them

- Prevent disruptions to training

- Improve enjoyment by tailoring exercise programs

- Phone calls, texts, emails, coffee breaks

- Discuss barriers and strategies

- Revisit client’s initial priorities (4 W’s: what, why, when and where)

- Re-emphasise the importance of exercise

- Adaptations to the program to suit client needs and preferences

- Discuss and agree with the client on the next steps.

In this topic, we focused on barriers which can impact client adherence and motivation along with strategies to overcome these and support the client in their health and fitness journey. You learnt about:

- Human behaviour change

- The Stages of Change Model

- Requirements for successful behaviour change

- Factors which affect exercise adherence

- Instructor actions to enhance exercise adherence.

WARNING

This material has been reproduced and communicated to you by or on behalf of UP Education in accordance with section 113P of the Copyright Act 1968 ( the Act ).

The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further reproduction or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act.

Do not remove this notice.