In this topic we will cover the following:

- Māori and Pasifika values and design

- Appropriation and cultural awareness

- Tangata whenua

- Whakapapa and whānau

- Tikanga Māori

- Pasifika values

- Case Study - Pink Shirt Day

‘Whiria te tāngata’ (Weave the people together)Whakataukī (Māori proverb)

Translations for Māori words are presented in brackets when they are first mentioned. You may wish to note any unfamiliar words and try to incorporate them into your daily life. Many words do not have a direct translation into English and meaning may be lost. If you wish to explore the meaning of a word in more depth, Māori Dictionary has a wealth of knowledge online, via the app, or available as a book.

Living in the 21st century, we are privileged to draw upon the collective knowledge of both our ancestors and contemporary leaders and community. With all the technological advancements we have at our disposal, we may second guess the need for applying traditional values into our personal or professional lives.

For those that choose to become designers, how do you consider traditional values in the design process?

For Māori, weaving together te ao Māori (Māori worldview), tikanga (process and practice), and mātauranga (knowledge) with their design practice may provide whakamana (empowerment) and a sense of mana whenua (belonging). In the following video, artist Te Kuru o Te Marama Dewes discusses what it means to work in Māori media.

Pasifika peoples make up a significant part of New Zealand’s identity. In fact, Auckland is the largest Polynesian city in the world with close to 200,000 Pasifika peoples. For Pasifika peoples, art and design may provide a space to tell their stories, explore their identities, and connect to their culture. In the following video, Niuean-Māori artist Lina Marsh talks about how she uses art to explore contemporary Pacific culture.

For non-Māori, understanding and respecting Māori values is part of being a good treaty partner. Pākehā (New Zealander of European descent) and Tauiwi (non-Māori, foreigner) have a duty under Te Tiriti o Waitangi (The Treaty of Waitangi) to respect the principles of partnership, participation, and protection. When embarking on the design process, consider how are you working in partnership with Māori communities? How are you encouraging participation and involvement of Māori? And how are you valuing and protecting Māori knowledge, values, interests, and taonga (treasures)?

Non-indigenous designers need to understand their role as an ally and partner in design initiatives where indigenous context, knowledge or forms are core to the outcome, and to consider ways to avoid holding spaces where indigenous designers could beBarbarich et al. 2017

Indigenous Design and Innovation Aotearoa (IDIA) have created a framework called Culture Centred Design (CCD). The framework ensures that design ‘outcomes are led, framed and informed by indigenous people, knowledge and ways of being’ (Barbarich et al. 2017). The three strands that form the CCD are tāngata (people), mātauranga (knowledge), and tikanga (process and practice).

IDIA have also created a Cultural Integrity Scorecard made up of 12 yes or no questions assessing indigeneity, design, integrity, and authenticity. Designers are encouraged to use this scorecard to assess appropriation and cultural awareness.

If your intellectual property includes Māori elements, your application may be referred to a Māori Advisory Committee.

What is cultural appropriation?

Using aspects of a minority culture, without knowing or understanding the cultural meaning behind them is cultural appropriation. This often leads to misrepresentation and causing offence to the original culture.

Red flags that indicate cultural appropriation include:

- The appropriated culture is exploited or oppressed by the person “borrowing” from the culture.

- Money is being made through the appropriated item, but the people of the original culture are not financially compensated.

- People are often insulted and looked down upon for having these features naturally, when someone else is praised for having them, without being from that culture.

What is cultural appreciation?

Cultural appreciation can be described as being inspired by aspects from a minority culture’s aesthetics and using them in a way that is respectful and inclusive of that culture. Often this means researching and communicating with members of that culture to make sure visual elements are used in appropriate contexts and with respect.

Guidelines for using Māori art

Before using any Māori art form you should understand what it means and consider if it is appropriate to use in the context you intend to use it.

- Do not use Māori art on products that may be deemed inappropriate for example underwear, cigarettes, or alcohol.

- Some motifs and customs should not be performed or worn by women. Always check for appropriate use.

- Receive permission before using songs, acts, or waiata for commercial purposes.

- Patterns should not be truncated, skewed, or bastardised in any form or shape.

- Research the meaning behind shapes and patterns you are wanting to use. Do not mix more than one style.

- Do not mix tā moko (traditional tattoo) patterns with whakairo (carving) or raranga (weaving).

Most importantly if you do not know... ask!

Case study: Thor Ragnarok directed by Taika Waititi

Thor Ragnorak was shot in Australia. The following steps were taken to respect indigenous values.

- Taika Waititi sought consultation and permission from the traditional indigenous owners of the land to make sure nothing they were doing was culturally insensitive.

- A Welcome to Country Ceremony was held to acknowledge the indigenous peoples and historic land ownership before filming began.

- Waititi made sure there were internship positions on his crew for Indigenous Australian young people interested in learning more about the film industry.

- Paid homage to both his own New Zealand Māori heritage and the indigenous culture of Australia by using the colours and motifs of the two indigenous flags in the design of the two main spaceships in the movie.

From Instagram update, 27 January by T Waititi 2021

Aotearoa, New Zealand is a special place to be. As a small island nation at the bottom of the Pacific, our history is rich in maritime stories.

Aotearoa was one of the last landmasses inhabited with most sources estimating settlement between 1320 and 1350 CE, so about 700 years ago. Oral history often tells of migration from Hawaiki in double-hulled waka (canoes).

Watch the following excerpt from The Aotearoa History Show for an introduction to exploration, migration, and discovery in Polynesia and Aotearoa.

Over the next few hundred years since their first journey, Polynesian settlers dispersed, settled, and created their own unique identities. Māori became the tangata whenua (people of the land) of the North and South Islands of New Zealand.

Migration has since brought more than 40 different Pasifika ethnic groups, each with its own culture, language, and history. The eight main Pasifika ethnic groups in New Zealand are:

- Samoan (47%)

- Cook Islands Māori (20%)

- Tongan (18%)

- Niuean (7%)

- Fijian (4%)

- Tokelauan (2%)

- Tuvaluan (1%)

- Kiribati (less than 1%) (Pasefika Proud 2016, p. 2)

Common stories of voyaging and migration unite many Pasifika and Māori cultures in shared values and cultural similarities.

To begin understanding Māori and Pasifika values, it is helpful to first consider how family and community are defined. Unlike a contemporary, western view, where a family is defined only by the immediate nuclear family of a father, mother, and siblings; Māori and Pasifika cultures perceive family to include extended, wider relatives, such as aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents.

In Māori culture specifically, a whānau (family) is the smallest unit of the community that forms a hapū (subtribe). These groups of hapū then form an iwi (tribe), and these group of iwi were also defined by the shared waka (canoe) during their initial migration.

Whanaungatanga

Whanaungatanga (nurturing relationship) is one of the values strongly embedded and carried over to contemporary application of day-to-day Māori values. As a community, whānau are encouraged to draw upon their collective strength. If a whānau is experiencing difficulty and unable to resolve it within their immediate whānau unit, they can seek support from the wider community or their hapū. And if they are still unable to find a resolution, the whānau unit can draw from the resources of the widder community of their iwi.

The whakataukī (proverb) ‘He waka eke noa - We are in this together/in the same boat’ describes this community spirit well.

Whakapapa, mihi, and pepeha

A Māori sense of self draws from the whakapapa (ancestral connection and lineage, genealogy). We need to acknowledge that not all Māori know their whakapapa or reo, often because of injustices and historical trauma due to colonisation including the 1955 Adoption of Children’s Act which saw thousands of Māori babies handed over to Pākehā families and all connection to the birth family severed (Hurihanganui 2019). Connecting or rediscovering one's whakapapa can be an emotional and difficult journey.

A Māori approach to mihi (introductions, greetings) will start with a whakapapa. This approach helps to bridge and position who the speaker is in relation to the world known to the people listening. A mihi can be brief or can tell a longer, more comprehensive history. It all depends on the occasion.

A mihi can be part of a pepeha (formal introduction). It includes a reference to where your parents, grandparents, and ancestors are from. If a person has Māori lineage, the introduction will include specific geographical features such as maunga (mountain), awa (river), and waka their ancestors come from. The speaker’s ingoa (name) will usually come near the end of the mihi or pepeha.

You may come across pepeha templates featuring the phrase “ko ___ tōku maunga” for example. This translates roughly to “___ is my mountain.” Please be aware that this has a very specific meaning and links to ancestral roots. It is more than a mountain near to where you were born or grew up. It is more than a mountain that you enjoy spending time near or on. For Māori, introducing themselves using maunga and awa is stating their tīpuna (ancestors).

Kaimahi (colleagues) Māori at Auckland Libraries created the following pepeha templates to help Māori, Pākehā (New Zealander of European descent), and Tauiwi (non-Māori, foreigner) introduce themselves.

From He kōrero mōku, Introducing yourself by Auckland Libraries, 2020

From Pepeha for Māori by Auckland Libraries, 2020

From Pepeha for Pākeha and Tauiwi by Auckland Libraries, 2020

From Pepeha for Pākeha and Tauiwi in Aotearoa by Auckland Libraries, 2020

Reo Māori Mai is also a great source of knowledge. If you would like alternative ways of incorporating your awa and maunga into your pepeha, please read their posts and many helpful suggestions:

Spend some time now to consider your pepeha.

Tikanga can be defined as correct procedure, customs, practice, and protocol.

Tikanga can also be seen as a practical approach to problem-solving, using common sense and untangling complicated problems by stripping superfluous, unnecessary blockages.

First let us consider three foundations as detailed by Curtis Bristowe in his TEDx presentation. Bristowe describes three unique Māori knowledge systems based on the power of observation. He places the importance of collective and spiritual wellbeing above the individual and materialistic needs.

- Kawa - The guiding philosophy. The collective aim. The communal goals. A clear and defined vision. It answers the question of ‘what we do’.

- Tikanga - The practice that supports the guiding philosophy. The collective beliefs and values that inform the attitude and behaviours, so that they are ethical and moral. It answers the question of ‘how we do it.’

- Kaupapa - A collective endeavour. Applying the above beliefs and values as a group and community. Answers the question of ‘who is involved’.

Although the three knowledge systems have their unique definitions, they are interconnected and meant to work in harmony as one.

The basic principles underpinning the following tikanga are common throughout Aotearoa. Note that every iwi has developed variations to each tikanga practice. This list is not exhaustive but provides a brief introduction to common tikanga and how they inform daily life.

- Tapu and noa

- Mana

- Utu

- Karakia

- Aroha

- Kōrero awhi

- Kotahitanga

- Kaitiakitanga

- Rangatiratanga

Tapu and Noa

Tapu can be defined as sacred, whereas noa is ordinary or not sacred.

Tapu places certain restrictions, especially surrounding the human body and its relationship with objects around it. These restrictions serve as a social norm and a protective measure for natural resources.

The following are some common tikanga that can be practised at home, performed in community and professional settings. It describes how tapu and noa relate to each other.

| Heads, pillows, and hats |

|

|---|---|

| Food, tables, and personal items |

|

| Speaking |

|

| Stepping |

|

In 2019, Wellington on a Plate was called out due to an advertising campaign featuring food being tipped over heads. In your graphic design practice, consider how you are respecting tikanga and how a diverse audience may perceive it.

Mana

Mana can be defined as the inherent self-value and power that everyone has.

Along with inherent self-value and power, mana is the respect for oneself and others. A person’s worth or value is not judged by their achievement, wealth, status, or power. Whether unemployed, earning a minimum wage, or a six-figure salary, everyone has inherent self-value. The attitude that you take on as an individual, the willingness to chip in and contribute to a community’s goals are examples of behaviour that defines your self-worth.

The word mana can also be combined with other words to form a variation to its meaning such as manaakitanga and mana manaaki.

Manaakitanga

A guiding principle of social conduct.

This act is shown through the different forms of hospitality, caring, and respect towards others. It is expected that this behaviour is given and received within the different social encounters

A practical example of this is to greet the visitors you have at your design studio with warmth, kindness, and respect no matter their race, religion, or physical appearance. It is also customary to offer some refreshments and make them feel relaxed and welcomed. Offering kai (food) and a cuppa is a simple example of manaakitanga.

Mana manaaki

The deliberate act of building up other people's mana.

Providing the awhi (support) to those around you can boost their mana. This act will make you feel good by giving and help others feel good as well. Practising mana manaaki will assist in creating a community that upholds good values and respect.

A practical example of this is acknowledging the good work done by a hoamahi (colleague) and celebrating their success together.

Utu

Utu can be defined as a principle of reciprocity.

Historically, during the time of tribal war and British colonisation, utu was strongly associated with the act of revenge. An eye for an eye. Grievances caused by others’ wrongdoings need to be counteracted to restore balance.

However, utu can also be a form of repaying kindness and gratitude. Traditions of gift-giving examples include gifting a pounamu (greenstone) and whakairo (carving), among others.

Karakia

Karakia are prayers or chants that serve as an acknowledgement of a higher power.

It is usually performed before and at the end of meetings or official proceedings. A karakia does not need to follow a specific religious practice and allows people of all faiths to join and set their intention for their journey to come. Karakia also helps to quieten the mood and calms the wairua (soul).

Here is an example of a karakia from Te Puni Kōkiri, the Ministry of Māori Development. This is a karakia whakamutunga, a closing prayer which you could use at the end of a meeting.

He Karakia Whakakapi

Kia whakairia te tapu / Restrictions are moved aside

Kia wātea ai te ara / So the pathways is clear

Kia turuki whakataha ai / To return to everyday activities

Haumi e. Hui e. Tāiki e! / Forward together!

Aroha

Love. Sincere, unconditional, pure and simple love.

It is easy to assume that the people that matter in your life know that you love and care for them. However, there can be the danger of taking the love we give and receive for granted. Just as the body needs its sleep and daily nourishments, it is a good habit to let the people you love know that you love them. Affirm this daily.

Expressing aroha and kindness starts with a simple kōrero (conversation). It can also be done through gestures, spending time to do some activities together, or gift-giving of simple, thoughtful items. Whatever the approach you choose, do not be afraid to share and express your aroha.

Kōrero awhi

‘Mā te kōrero, ka ora’ (A little chat can go a long way.)Whakataukī

Kōrero awhi is communicating clearly, positively, and with aroha to others.

Kōrero awhi helps whānau, friends, and colleagues to relate and feel connected to one another.

Be Fly is a creative and strategic agency that aspires to innovate creative solutions with mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge). The team is lead by Johnson MacKay, who has a Māori whakapapa, and in the following 3 minutes clip, shares how the team uses kōrero to build an inclusive work environment.

Kotahitanga

Kotahitanga can be defined as unity or togetherness.

The base word is made up of tahi, meaning one, individual or single. However, in kotahitanga, it discards its singularity and embraces the collective.

The kotahitanga pin was designed by graphic designers Stephen and Scott Bolton McCarthy in response to the attack on the Muslim community in Christchurch. The pin symbolizes embracing the differences in culture, race, and religion, and acknowledging the Muslim community as part of the bigger Aotearoa family.

From Best 2019 Kotahitanga 4 by Designers Institute of New Zealand, 2019

Kaitiakitanga

Kaitiakitanga can be translated as stewardship or guardianship.

‘Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua’ (I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on my past.)Whakataukī

This whakataukī (proverb) describes the Māori perspective of time. It represents the way of looking at the past, the present, and the future as interconnected. That life serves as a continuous cycle.

Western views see the past as history. It is positioned behind a person and perhaps referred to only occasionally. Importance is placed on the future as the sole focus to reach one’s goals and aspirations.

Te ao Māori (the Māori world view), places equal importance between the past and the present. Lessons, experiences, and the presence of the ancestors inform their decisions in the now. And in the present, we need to always consider how we will be a good ancestor to future generations.

The concept of environmental stewardship is a common practice of indigenous cultures around the world. In Aotearoa, Māori pioneered this concept, and it is now embraced by local and international residents. The act of preserving, sheltering, and protecting the environment is a responsibility shared by everyone.

In the following example, we will look at how David Trubridge, a sculptural lighting designer of British origin based in Hawkes Bay, has applied kaitiakitanga and nature observation in his design practice. Watch the following short video.

The synergy achieved with nature is exemplified by Trubridge’s approach in drawing inspirations from nature, as well as his company’s application of kaitiakitanga. With his background as a naval architect, Trubridge sees objects such as the corals, hīnaki (fish traps), and kina (sea urchins) as the basis of beautiful forms and structure.

Image of Koura lighting fixture, © David Trubridge

An excerpt of an interview with distributor Wakanine describes Trubridge’s approach:

‘I saw a minute kina shell dropped on the ice by a bird. The shell had absorbed enough heat from the sun to melt a little of the ice around it, causing it to settle into its own miniature blue ice cave.

This taught me the vital importance of detail. It showed me how I can use my camera and telephoto or macro lenses to isolate just these details. In this way I can home in on the essence and structure of the landscape.

This is where the truth lies – not the panoramic sweep of everything and nothing, but in its smallest component parts. These are patterns and structures of nature and of life – and they led me to understanding the patterns and structures of designs.’ (Trubridge n.d.)

Rangatiratanga

Rangatiratanga can be defined as leadership.

Traditionally the position of leadership is passed down through family lineage. However, in a modern context, the values can still be applied. The position of leadership serves as an opportunity to weave people together. Being in a position of leadership does not grant a heavy-handed and authoritarian approach to leading. Rangatira (chiefs) need to consider the people’s voices when making significant decisions, and often the voice of the majority is respected.

Migration has brought more than 40 different Pasifika ethnic groups to New Zealand. Pasifika people are known for their hospitable nature and might greet you with one of these Pasifika greetings.

“Talofa lava, malo e lelei, kia orana, taloha ni, fakalofa lahi atu, ni sa bula vinaka, kia ora, welcome”

Many of the values we have covered in tikanga Māori are shared by Pasifika cultures as well. In this subtopic we will look at how Pasifika values are applied through day-to-day community activities.

Family

The cultural importance of family is paramount as we will see in the following video from Le Va - a Pasifika organisation to support Pasifika families and communities to unleash their full potential. Watch the first six minutes and take note of how values such as faith, generosity, respect, serving others, family, and looking after older people, is described by fathers of Pasifika descent.

Va

According to Le Va, the va can be defined as the space that relates. Traditionally, for Pasifika people, sacred relationships exist between people as well as between people and the environment, ancestors, and the heavens. To nurture the va is to respect and maintain the sacred space, harmony, and balance within relationships.

The next video discusses va and its relationship to environment from a Samoan perspective.

Pacific values

Tapasā, the cultural competencies framework for teachers of Pacific learners, highlights nine Pacific values (Te Kete Ipurangi n.d.). This list is not exhaustive and may vary between different groups.

| Reciprocity | It is expected to apply the reciprocal act, especially to return favours, gifts, and other acts of kindness. |

| Relationships | Building and nurturing relationships are of high importance to Pasifika people. |

| Collectivism | The collective approach triumphs over the individual approach. The community perception is highly valued, and activities such as teamwork, consultation, and engagement with others are applied to achieve common goals and consensus. |

| Service | Serving others is an opportunity cherished and sought by Pasifika people. It is a significant part of their lives at home, at church, or in the community. |

| Respect | Respect is a value taught from an early age and is often a reflection of home environment. The culture at home includes showing respect towards elders, parents, women, children, and people in positions of authority. |

| Spirituality | Spirituality and the Christian faith are an important part of Pasifika people’s lives. An example of spirituality in practice will be to start and end the day with a prayer and the blessing of food. |

| Leadership | Leadership at home and community may have different contexts. Leaders will take on a different leadership style, but a common approach will be to lead from behind and respect community wishes. |

| Family | Family’s interest is often placed as the highest priority. Many Pasifika peoples live in extended families, and for many, the family is the centre of the community and their way of life. An individual will always identify themselves within the context of their families and wider communities. |

| Love | Love is a universal value that guides Pasifika in their day-to-day activities. In the Pasifika context, love is shown by care, kindness, and often by putting others before themselves. |

Community art practice - Tivaevae and Tapa Cloth

The Pasifika community art practices embody the practical approach of the nine values. These art practices are traditionally done by women in groups and gifted at important family events.

Tivaevae is the art of quilting, characterised by bold complimentary colours and usually consists of symmetrical floral patterns. The value of a tivaevae is not measured by monetary value or production cost. The importance is placed on the love and patience that the makers have put into making a stunning work of art. Cook Islands women often described the tivaevae as being "something from the heart".

The following video from Te Papa Museum illustrates the importance of tivaevae as part of Pasifika Samoan culture.

Tapa cloth is a decorative cloth made from the inner bark of various trees. It can be decorated by rubbing, stamping, stencilling, smoking (Fiji: "masi Kuvui") or dyeing. The patterns of Tongan, Samoan, and Fijian tapa usually form a grid of squares, each of which contains geometric patterns with repeated motifs such as fish and plants, for example four stylised leaves forming a diagonal cross. Anecdotal stories mentioned that the village women can tell a person’s expertise in creating a tapa just by hearing the rhythm of their tapa making, which was made by beating parts of the bark of the mulberry tree into thin paper-like pieces.

Watch the following video from Te Papa Museum that illustrates the importance of the tapa cloth as part of Pasifika culture.

The following case study looks at how a combination of Māori and Pasifika values can be applied in design campaigns today.

The Pink Shirt Day campaign was originally started by a group of students in Canada in 2007 as a response to bullying towards a person with a different sexual orientation. The campaign has since been adopted worldwide and successfully celebrated in Aotearoa since 2009.

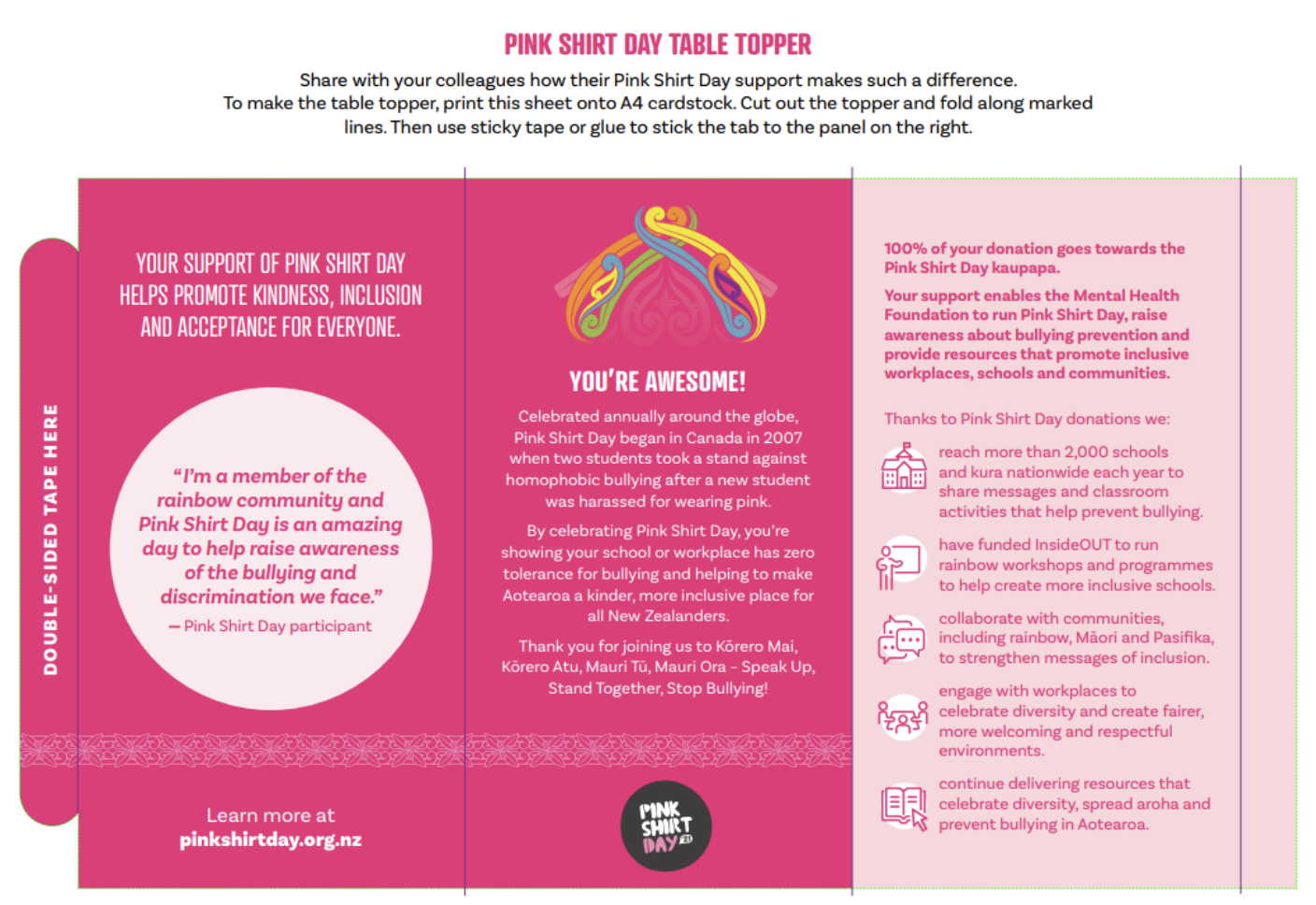

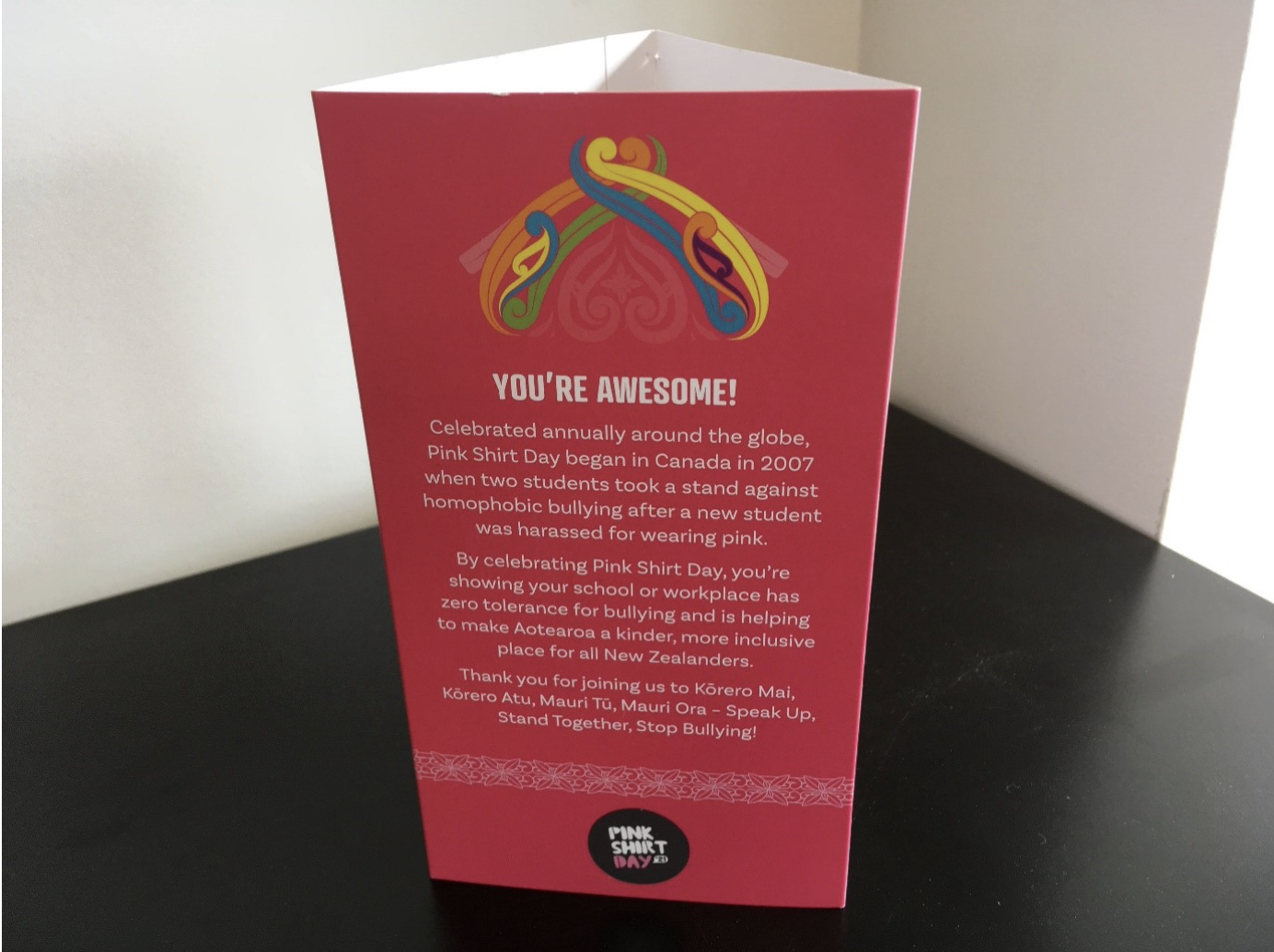

The following image is a table-topper designed on an A4 size paper and foldable as a standalone piece, complete with its folding line and where to tape or glue the seams. Three key Māori values informed the design; aroha and kindness, kōrero awhi, and mana manaaki. It also incorporated the interlocking Māori koru (fern frond) symbols at the top and the Pasifika frangipani patterns at the bottom.

We examined why Māori and Pasifika values should be taken into consideration in the design process.

- Māori artists may achieve whakamana and a sense of mana whenua by weaving together te ao Māori, tikanga, and mātauranga with their design practice.

- Pasifika artists may find that art and design provide a space to tell their stories, explore their identities, and connect to their culture.

- For non-Māori, understanding and respecting Māori values is part of being a good treaty partner and respecting the principles of partnership, participation, and protection.

We introduced two tools designers can use to ensure cultural awareness and to protect against appropriation.

- Culture Centred Design (CCD) to ensure design ‘outcomes are led, framed and informed by indigenous people, knowledge and ways of being’ (Barbarich et al. 2017).

- Cultural Integrity Scorecard to assess indigeneity, design, integrity, and authenticity.

Whakapapa and whānau are important to Māori and Pasifika. Whanaungatanga (nurturing relationship) is of high importance and whānau are encouraged to draw upon their collective strength. Mihi and pepeha often include a whakapapa and help to position the speaker in the world known to the audience.

When embarking on a design process in a New Zealand context, tikanga Māori should be considered to ensure content is appropriate and does not cause offence or misappropriate. Some important tikanga to consider includes;

- Tapu (sacred) and noa (ordinary, not sacred)

- Mana (spiritual power), manaakitanga (hospitality), mana manaaki (building up others mana)

- Utu (reciprocity)

- Karakia (prayer)

- Aroha (love)

- Kōrero awhi (open communication)

- Kotahitanga (unity)

- Kaitiakitanga (guardianship)

- Rangatiratanga (chiefly autonomy).

Pasifika peoples are an important audience in New Zealand and we must also show consideration to their values including;

- Family and community

- Va – The sacred space that relates.

- Reciprocity

- Relationships

- Collectivism

- Service

- Respect

- Spirituality

- Leadership

- Family

- Love.

We have introduced some Māori and Pasifika values. Understanding and learning about te ao Māori, tikanga, and Pasifika values is a long, personal journey and you are encouraged to continue exploring these topics.

Additional resources

Here are some links to help you learn more about this topic.

It is expected that you should complete 12 hours (FT) or 6 hours (PT) of student-directed learning each week. These resources will make up part of your own student-directed learning hours.

- The Aotearoa History Show - Season 2 Ep 2: Māori: The First 500 Years

- The Aotearoa History Show - Season 2 Ep 6: Native Land Court

- The Aotearoa History Show - Season 1 Ep 12: Post-War New Zealand

- Ethics for designers

- Ethical issues in graphic design

- Design social responsibility: Ethical discourse in visual communication design practice

- Ethics in design: Cultural influence

- Ethical design: Practical getting started guide

- Auckland Museum: Te Ao Tūroa - Māori Natural History gallery

- Auckland Museum: He Taonga Māori - Māori Court

- The Māori dictionary

- Learning Te Reo

- Community groups