The first step to meeting project administration requirements would be to identify them and understand their underlying framework. Previously, you have looked at the contract documents to determine the requirements needed in ensuring the quality of materials and work. This section will now consider how the construction contract itself applies to the administrative processes carried out in the project, specifically the payment systems, contract variations, and claims.

Project Administration

Project administration refers to the implementation of administration and business processes for the works involved in a construction project. An effective project administration system is in place when deadlines and compliance requirements are met. Tasks involved in project administration are to:

- Coordinate with the site manager and project manager and assist in project management processes;

- Supervise the project team in administrative functions;

- Perform analysis and evaluation on project progress;

- Conduct meetings and consultations for administrative discussions and project updates;

- Coordinate with the supplier, prepare invoices and purchase orders;

- Document and manage the contract and other project administrative documents; and

- Accomplish other day-to-day administrative tasks of the project.

Although specific project administration tasks are already assigned to project administrators, the supervisor is expected to make sure that project administration requirements are achieved. The supervisor is expected to be on top of administration procedures, especially in matters concerning contracts and payments.

Contract administration

Contracts administration refers to management procedures implemented to make sure that all parties fulfil their respective obligations as specified in the agreements and standards stipulated in the construction contract.

The role of the contracts administrator

The contracts administrator is responsible for the management of the construction contract on behalf of the project and organisation. This includes managing paperwork associated with contracts, managing variation orders, and liaising with suppliers, subcontractors, traders, project managers, and clients.

The role of the superintendent

Apart from the contracts administrator, the superintendent will also be involved in the administration of a construction contract. In general, the role of the superintendent is determined by the construction contract and the applicable legislation. The superintendent is expected to perform two distinct roles: to act as agent for the client and to act as an independent certifier. The table that follows summarises the functions associated with the roles of the superintendent.

|

As agent for the client |

As an independent certifier |

|

certify claims related to:

|

The superintendent is expected to act in the client’s best interest as an agent but must act honestly and impartially as a certifier. As such, the influence of the client on the superintendent is limited to the superintendent's role as an agent.

The role of the supervisor in contracts administration

As a supervisor, you are principally responsible for monitoring all activities that happen on site, including the administration of contracts. As a supervisor, you must be knowledgeable with the contract requirements to make sure that the site activities are done in fulfillment of contractual obligations. You must be familiar with the payment systems in place so that all relevant payments made can be properly monitored. You must also be adept in dealing with contract variations and insurance claims.

Overall, as a supervisor, you are expected to understand and effectively apply contract technicalities on site activities. You are expected to successfully oversee project administration on site.

Types of construction contracts

In the construction industry, the contract is a legally binding agreement in between the client and the contractor which specifies the scope of work, project schedule, total project cost, payment details, terms and schedule and provisions for dispute resolution.

One of the key elements to understanding the administrative implications of the construction contract is to determine the type it falls under. In Australia, most construction contracts are either fixed price (lump sum) or cost plus contracts.

The Australian Accounting Standards Board (AASB) defines fixed price and cost plus contracts as:

- A fixed price contract is a construction contract in which the contractor agrees to a fixed contract price, or a fixed rate per unit of output, which in some cases is subject to cost escalation clauses.

- A cost plus contract is a construction contract in which the contractor is reimbursed for allowable or otherwise defined costs, plus a percentage of these costs or a fixed fee.

Fixed price or lump sum contracts are often used in projects where the design is either completed or detailed enough for the contractor to accurately price, or in projects where the nature of work is well defined. Cost plus contracts, on the other hand, are often used when the scope of works is not yet clearly defined and when the client’s budget has not been finalised.

Cost plus contracts may either be:

- Cost Plus Fixed Percentage

- Cost Plus Fixed Fee

- Cost Plus with Guaranteed Maximum Price Contract

- Cost Plus with Guaranteed Maximum Price and Bonus Contract

To identify the required payment scheme and take appropriate actions, you must first understand the type of contract used for the project.

Standard forms of contract

After you have established the contract type, you would need the standard form used for the contract. Establishing familiarity with standard contract forms will give you the general idea of its provisions. Consequently, this will help you identify the project administration requirements enclosed in the contract.

In Australia, construction contracts are usually established using standard forms as basis. In a research conducted by the Melbourne Law School in 2014, 68% of the contracts reported upon were based on standard forms. From the same research, it has been found that the use of these standard forms varies depending on the contract value, project location, contracting sector, and whether the contracts were head contracts or subcontracts/trade contracts. The same research also notes that the decision to use standard forms is largely the decision of the client/principal: in more than 80% of the cases, it has been reported that the principal (55%) or the principal’s lawyer (26%) were responsible for choosing the standard form. The research also cites ‘familiarity with the form’ as the dominant factor in using standard forms of contract.

Australian Standards

From the Melbourne Law School 2014 research, close to 70% of the projects using a standard form utilised forms that belong to the Australian Standards (AS): 23% used AS 4300, 18% used AS 4000, 17% used AS 2124, while 14% used AS 4902.

While there are other standard forms in the AS suite, this section will be primarily discussing the four mentioned standard forms for this section.

AS 4300

AS4300, formally known as AS 4300-1995 General conditions of contract for design and construct, is commonly used for commercial projects where the contractor will be involved in the design of the project.

The following table summarises procurement methods for which AS 4300 is commonly used:

|

Procurement method |

Set-up |

|

Design and Construct |

The client provides the design brief and project requirements while the contractor develops the design based on the brief provided. The contractor is also responsible for the construction of the project. |

|

Design, Development and Construct |

The client provides the project requirements and the preliminary design while the contractor is responsible for design completion and construction management. |

|

Design, Novate and Construct |

The client employs a design team for the initial design development and then eventually transfers the responsibility of design completion to the contractor. The original design team is then expected to work for the subcontractor for design completion under novation. The contractor is also responsible for construction management. |

Under contracts based on AS 4300, the contractor is accountable for all aspects of design and construction, which usually results in a faster construction phase.

AS 4000

One of the most frequently used form of contract is the AS 4000-1997 General conditions of contract, or AS 4000. AS 4000 is a ‘construct only’ form of contract, which means it does not include provisions for instances where the contractor is also in charge of the design. Some of the notable provisions of this form of contract include:

- The validity of claims, for the most part, is not bound by the prescribed timeframe (with a few exceptions e.g. latent conditions).

- The superintendent can allocate resulting delays to respective contributing causes.

- The effect of latent condition is deemed as a variation. (Variations will be discussed further in Section 2.3)

- Arbitration is the default method for resolving disputes.

- Extensions of time requests are considered granted if the supervisor fails to respond to the contractor within 28 days after receiving such requests.

AS 2124

Another widely used standard form of contract is the AS 2124-1992 General conditions of contract, or AS 2124. AS 2124 is also a ‘construct only’ form of contract. In this form of contract:

- The contractor can claim an extension of time (EOT) for delays which occur before practical completion and are caused by any event beyond the contractor’s reasonable control. (Extensions of time will be further discussed in Section 2.4)

- Validity of claims is bound by the prescribed timeframe.

- When the contractor fails to reach practical completion by the date agreed, the contractor is automatically obligated to pay the client for liquidated damages.

- The amount that can be claimed by a contractor for a valid cause of delay is uncapped.

- The price of a variation does not necessarily have to be agreed upon before starting the variation work.

AS 4902

AS 4902-2000 General conditions of contract for design and construct, or simply AS 4902 is another widely used standard form of contract for design and construct projects. AS 4902 follows the risk profile, drafting and format of the AS 4000. Some key features in AS 4902 are the same as those in AS 4000, only this time in the context of design and construct projects.

Comparison of standard forms of contract

A comparison of the basic features of the discussed standard forms of contract (AS 4300, AS 4000, AS 2124, and AS 4902) is provided on the table below:

|

Basic Features |

AS 4300 |

AS 4000 |

AS 2124 |

AS 4902 |

|||

|

Lump sum price: fixed price, fixed timeframe |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

|

Fixed timeframe: contractor must achieve agreed date for practical completion or else, liquidated damages will apply. |

Yes, if provided for in the annexure |

Yes |

Yes, if provided for in the annexure |

Yes |

|||

|

Practical completion: the construction project can be used and occupied before all works are completed. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

|

Contractor design obligations |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

|||

|

Variations: The contract prescribes a process for dealing with variations. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

|

Extensions of time (EOT): the contractor may claim extensions of time for delays occurring before the date for practical completion |

Yes, if the delay is caused by events specified in the contract or annexure |

Yes, if the delay is caused by a ‘qualifying cause of delay’ |

Yes, if the delay is caused by events specified in the contract or annexure |

Yes, if the delay is caused by a ‘qualifying cause of delay’ |

|||

|

Latent conditions: The contractor is entitled to claim an extension of time (EOT) and additional costs if the contractor encounters a latent condition (subject to the prescribed notice procedure.) |

Yes |

Yes, deemed as a variation |

Yes |

Yes, deemed as a variation |

|||

|

Provisional sums: client and contractor agreement on a 'provisional' sum in cases where design is not yet sufficiently developed to determine a fixed price. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

|

Separable Portions: Allows work to be divided into portions, each potentially having a different access date, date for practical completion, and liquidated damages rate. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

Note that these forms of contract feature provisions for lump sum arrangements. However, clients and contracting parties may still opt to use these standard forms for cost plus arrangements by adding amendments in their agreements.

Understanding the contract forms is helpful in reviewing contracts and determining specific provisions for project administration. Reviewing and understanding the provisions of the contract are crucial steps in avoiding disagreements, resolving disputes, and identifying project administration requirements.

Watch the video below to watch Master Builds Q&A ‘Fixed Price or Costs Plus Contracts’ – Home in WA 436

Watch the video below to learn more about cost-plus contracts.

Follow this link to learn more about the different types of construction contract explained: https://www.turtons.com/blog/how-to-choose-between-the-different-types-of-construction-contract

Payment systems

The contract between the client and the contractor formalises the agreement between the two parties on the payment system, or how the contractor can expect to be compensated for the work rendered on the construction project.

Similarly, contracts between the contractor and subcontractors, as well as contracts between the contractor and suppliers, formalise the contractor’s commitment to pay what is due for the services and materials delivered.

Thus, you will have to carefully review the contracts to understand the payment schemes and conditions agreed upon and implement them in project administration procedures.

Deposits

In terms of a construction contract, the deposit refers to the initial payment made by the client which is part of the full price of the contract (i.e., down payment). For building projects, deposit amounts required by law usually range from 5-10% of the total contract price, depending on the State or territory.

The table that follows shows the deposit amounts mandated by law for building projects in each state and territory.

|

State or Territory |

Deposits for Building Projects |

|

Australian Capital Territory |

No limit on initial deposit, however, usually up to 10% of total contract price |

|

New South Wales |

No more than 10% of total contract price |

|

Northern Territory |

No more than 5% of total contract price |

|

Queensland |

No more than:

|

|

South Australia |

No more than:

|

|

Tasmania |

No more than:

|

|

Victoria |

No more than:

|

|

Western Australia |

No more than 6.5% of the total contract price for contracts between $7,500 and $500,000 |

Progress payments

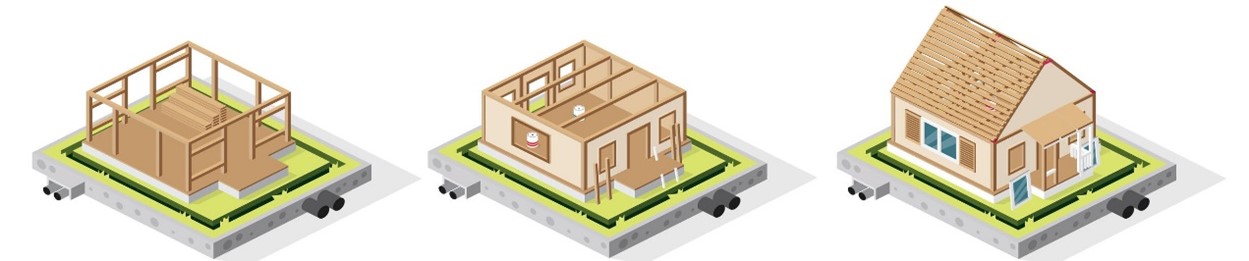

Progress payments are payments made according to a set schedule and the percentage of work completed. This payment system specifies stages in the construction work for which the contractor becomes eligible to receive an agreed amount (part of the total contract price). In general, after the payment of deposit, payments are made after the completion of the following stages:

Base or slab stage

This is the stage where foundations and slabs are laid. This includes concrete pouring for slabs and footings, installation of slab drainage, moisture barriers, and termite protection.

The completion of this stage depends on the floor type. For timber floors, the base or slab stage is complete when concrete footings for the floor have been poured and brickwork has been built to floor level. For timber floors with no base brick work, this stage is complete when stumps, piers, and columns are complete. For suspended slab floors and floors constructed after interior walls, this stage can be considered complete after concrete footings are poured. For concrete floors, this stage can only be considered complete when the concrete floor is fully finished.

Frame stage

This stage includes the erection of beams, columns, roof trusses, and other structural frames. This also includes the installation of sheeting, insulation, gutters, and conduits for electrical and plumbing.

The frame stage is completed when the frames have been inspected and approved by a qualified building surveyor.

Lock-up stage

This is the stage when doors and windows are installed, and the project has reached a point where it can be ‘locked up’. This stage is considered complete when all wall cladding, roof covering, and external doors and windows are fixed.

Fixing stage

This is the stage when all fit-outs components, fixtures (plumbing, electrical, etc.) and fittings are installed. This stage also covers the installation of tiles, cornices, cabinets, and sinks. Fixing stage is completed when all fixtures and fittings have been fixed in position.

Practical completion

This is the point in construction where major works have been completed and the building is practically suitable for occupancy. After a certifier approves practical completion, the contractor becomes eligible to receive final payment. This stage will be discussed further in Chapter 5.

Schedule of payment in the contract

In general, schedules of payment specify the stages and dates when payments are expected to be made as well as their corresponding amounts.

In Victoria, state legislation (Domestic Building Contracts Act 1995) prescribes the progress payment amount for each completed stage. For projects where the contractor is expected to manage the construction for all stages, the client is expected to pay the percentage of the total contract price summarised in the next page.

|

Payment Stage |

Payment Amount |

|

Deposit |

5%* of the total contract price |

|

Base |

10% of the total contract price |

|

Frame |

15% of the total contract price |

|

Lock-up |

35% of the total contract price |

|

Fixing |

25% of the total contract price |

|

Practical Completion |

10%* of the total contract price |

*Note: Deposit amount depends on the total contract price

In States or Territories where legislation does not specifically control the amount of progress payments, the terms will depend on the negotiation between the client and the contractor. However, all terms for progress payments must always be in relation to the work completed on site, e.g. the contractor cannot claim more than 50% of the contract price, including the deposit, until at least 50% of the work has been completed on site.

Payment claims and payment schedules

Payment claims are documents that are issued to formally request payment from a hiring party (e.g. client) by a hired party (e.g. contractor) in a construction project. The hiring party is then required to respond to that claim within a certain period, either by paying the amount claim or by issuing a payment schedule. A payment schedule indicates the amount which the hiring party intends to pay.

Security

A construction contract would often specify provisions for security or means for the client to secure that the contractor fulfills their obligation. Among the most common types of security used in construction projects include retention money, insurance bond, bank guarantee, and guarantee from related party.

Retention money

Retention money refers to the amount withheld by the hiring party (e.g. the client in a client-contractor agreement; the contractor in a contractor-subcontractor agreement) to make sure that the work is properly completed. Retention money is usually 5 – 10% of the progress payment amount. The retained amount is paid at the completion of the project when all items in the punch list and all requirements have been deemed complete.

Insurance bond

An insurance bond essentially serves as a ‘promise’ issued by a third-party financial institution (i.e. an insurance company) to pay a certain amount of money when a specified event occurs. For insurance bonds, the insurance company will charge the contractor a fee that corresponds to the assessed financial risk and insurance coverage.

Bank guarantee

Bank guarantees are similar to insurance bonds in a sense that a third-party financial institution (this time, a bank) guarantees payment of a certain amount for a specific event. However, apart from fees, the bank may also require a cash deposit or a property mortgage from the contractor.

Guarantee from related party

This guarantee is issued by a person or organisation related to the contractor (e.g. a director, a shareholder, or in cases where the contractor is a subsidiary, the parent company). This guarantee states the issuing party’s commitment to stand behind the contractor and be responsible for any failure to fulfil contractual obligations on the contractor’s part.

Security of payment

Apart from identifying payment details specified in the contract, you must also be familiar with the laws that regulate procedures on construction project payments. Familiarity with these laws will help you make sure that all payments related to the project are made fairly. This will also help you in resolving disputes that may arise.

As in the previous discussion, legislation for each State and Territory mandates certain aspects of construction contracts and payments. Laws are enforced in each State and Territory to protect the interests of all parties engaged in a construction contract.

Specifically, all contractors and subcontractors have legal rights to security of payment, which means they have the right to receive due payment according to what has been outlined in their contract. For example, contractors and subcontractors are entitled to receive their progress payments on time.

Below is a summary of the primary security of payment laws for each State and Territory:

|

State/Territory |

Legislation |

|

Australian Capital Territory |

Building and Construction Industry (Security of Payment) Act 2009 |

|

New South Wales |

Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act 1999 |

|

Northern Territory |

Construction Contracts (Security of Payments) Act 2004 |

|

Queensland |

Building Industry Fairness (Security of Payment) Act 2017 |

|

South Australia |

Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act 2009 |

|

Tasmania |

Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act 2009 |

|

Victoria |

Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act 2002 |

|

Western Australia |

Construction Contracts Act 2004 |

In general, security of payment laws cover most types of construction work, such as building work, demolition, plumbing, electrical work, building design and architecture and more.

Security of payment laws also specify the following:

- Payment claim requirements and timeframes

- Payment terms

- Payment schedule and notice of dispute timeframes

- Payment schedule and notice of dispute requirements

- Consequences of failing to provide payment schedules/notice of disputes

- Consequences of failing to pay undisputed amount

- Consequences of failing to pay determined amount

- Adjudication timeframes and requirements

Apart from specifying requirements and timeframes for issuing payment claims and responses, security of payment laws also provide instructions for adjudication, or the legal procedure for resolving payment disputes. Adjudication schemes for each state are generally similar, although timeframes and specific steps may vary. Therefore, it is important to understand how relevant laws work on your region.

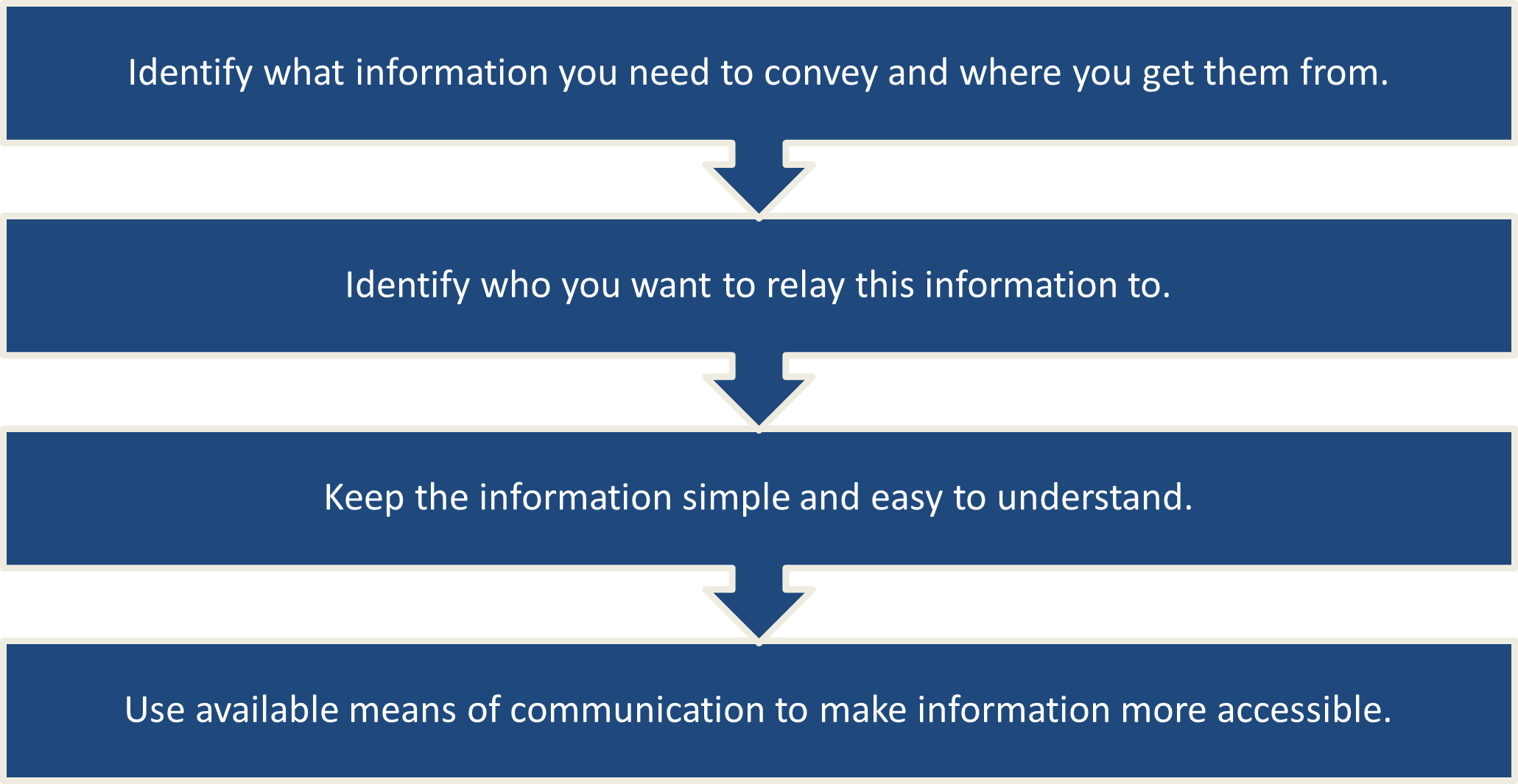

Identifying project administration requirements

Identifying In your role as a supervisor, it is crucial to identify project administration requirements to properly supervise administrative activities on site. In general, project administration requirements depend heavily on the provisions stated in the contract as well as the legislation in force. To identify project administration requirements, you will have to:

Review contracts

Refer to the contract to understand the payment systems in place. Take note of the amount of deposits, retention money, and progress payments expected, as well as the dates scheduled for payment. Take note also of the contract provisions for delays, variations, and extensions of time.

Be familiar with local legislation

Determine if the provisions of the contract are aligned with the relevant laws. Be aware of the legal obligations of clients, contractors, and subcontractors. Also, become familiar with legal procedures relevant to filing claims and complaints and settlement of disputes.

Consult with the management of your organisation

Determine how contract and legal administrative requirements will apply to the administrative procedures in the project. Determine the documents needed, access document templates, and plan relevant procedures. Review the management protocol and identify the people in charge of specific administrative procedures (e.g. Who is authorised to receive payments? Whose signature is needed to validate a document? Who is allowed to file a claim on behalf of the company? etc.). Consult with the administration team for schedules of relevant activities.

As a supervisor, you will have to make sure that project administration procedures on site are in accordance with your organisation’s policies, contract requirements, and the law.

Payment claims

Payment claims are formal payment requests issued by the contractor to the client, or a subcontractor to the contractor, for services rendered under a construction contract. Work and services provided for a construction project can be claimed even if the contract is not written, does not include progress payments or has only a single payment to be made when the work is completed.

Who is entitled to make a payment claim?

Every individual who has rendered work or who has provided goods or services in a construction project are legally entitled to serve their clients payment claims. In particular, the following individuals have legal rights to make payment claims:

- Contractor (against clients)

- Subcontractor (against contractors)

- Supplier (against buyers e.g. subcontractors, contractors, or clients)

- Plant and Equipment Hirer (against clients)

- Consultant (against clients)

What can an eligible individual claim for?

An eligible individual may claim for:

- construction work done

- construction material or plant you have provided

- consulting services you have provided

- interest on overdue progress payments

- your losses and additional costs due to work being deleted from your contract while you suspended work

- cash security and retention money

- the final payment, at the end of a contract

As a supervisor, you are expected to manage matters related to payment claims effectively. While the actual filing and paperwork may be delegated to other people in the team, you need to be aware of the status of payment claim, properly administer necessary procedures, and respond accordingly. In some cases, you will even be authorised to issue payment claims on behalf of your company.

Requirements for payment claims

In general, the laws on the security of payments require payment claims to:

|

Requirement |

ACT |

NSW |

NT |

QLD |

SA |

TAS |

VIC |

WA |

|

Identify construction work, or goods to which it relates |

P |

P |

|

P |

P |

P |

P |

|

|

Indicate/specify monetary amount claimed |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

|

Be served on person, who under the construction contract is or may be liable to make payment |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

|

State that it is made under the Act |

P |

P |

|

|

P |

P |

P |

|

|

Be the first payment claim in respect of a reference date under the contract 1,2 |

P |

|

|

P |

P |

P |

P |

|

|

Be in writing |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

|

Be addressed to the person to whom it is served |

|

|

P |

|

|

P |

|

P |

|

State the name of claimant |

|

|

P |

|

|

P |

|

P |

|

State the date of the claim |

|

|

P |

|

|

|

|

P |

|

Itemise and describe the obligations that the contractor has performed in sufficient details |

|

|

P |

|

|

|

|

P |

|

Be signed by the claimant |

|

|

P |

|

|

|

|

P |

|

Contractor must provide a supporting statement with payment claim. |

|

P |

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 In New South Wales, the concept of reference date is deleted and replaced with entitlement of a claimant to submit one payment claim per month.

2 In Queensland, The BIF Act states that if a construction contract is terminated and the contract does not provide for a reference date beyond termination, the final reference date for the contract is the date the contract is terminated.

Payment schedules

When a payment claim has been served to a respondent, they are legally required to respond to that claim within a required timeframe, either by paying the amount claimed or issuing a payment schedule. A payment schedule is a response when you cannot pay any or all claimed amounts immediately and will therefore delay full payment. If the respondent does not agree with the claimed amount, they must issue a payment schedule; otherwise, they will be liable for the full amount claimed.

Requirements for payment schedules

The table below provides the payment schedule requirements for each State and Territory:

|

Requirement |

ACT |

NSW |

NT |

QLD |

SA |

TAS |

VIC |

WA |

|

Identify payment claim to which it relates |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

|

Indicate the respondent’s proposed amount of payment |

P |

P |

|

P |

P |

P |

P |

|

|

Reason why payment is lower & why money is being withheld (if applicable) |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

|

Identify amount of claim which is an excluded amount |

|

|

|

|

|

|

P |

|

|

Include any other information prescribed / be in the prescribed form 1 |

P |

|

|

P |

|

|

P |

|

|

Be in writing |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

P |

|

Be addressed to the claimant or signed |

|

|

P |

|

|

|

|

P |

|

State the name of the party giving notice and the date of the notice |

|

|

P |

|

|

|

|

P |

|

State the reasons for why the claim is not in accordance with the contract (if applicable) |

|

|

P |

|

|

|

|

P |

1 No form prescribed in the States of Queensland and Victoria at the time of writing. Check your local legislation for updates.

Responding to payment claims

Apart from knowing how to make payment claims, it is also important for a supervisor to understand how to issue a payment schedule when it is the applicable response.

To issue payment for the work or goods rendered for a construction payment, you need to:

- Review the claim. Evaluate the grounds of the claim and determine the proper response. Is it aligned with what is stated in the contract? Is the amount of claim justified? Should the claim be paid, or should you issue a payment schedule? Review the claim thoroughly and decide on the appropriate response.

- Make sure that you have the authority to respond to the claim on behalf of your organisation. You must be an authorised person to authorise a payment or issue a payment schedule. If not, consult with someone who is (e.g. a finance or procurement officer or the project manager).

- Check the Security of Payment Act and relevant laws enforced in your State or Territory. As mentioned in the discussion of making payment claims, laws are subject to amendments and changes may be enforced. Thus, it is important to regularly check the local legislation for updates. Take note of required response deadlines and time frames and be wary of penalties.

- Make a written payment schedule when your organisation does not intend to pay the claimed amount fully. Access prescribed claim forms, if any, and fill them out accordingly. Indicate the scheduled amount, and make sure that your payment schedule addresses the requirements of your local legislation. Attach documents that support your payment schedule (e.g. computations, invoices, etc.)

- Indicate reasons for not paying the claimed amount or for withholding payment. Also indicate reasons for non-payment (when applicable). This will be helpful should disputes arise. Any reason not stated in the payment schedule (or corresponding attachments) cannot be raised in defence of the respondent.

- Address the response to the claimant and sign the response. Make sure that the claimant’s details are stated in the response. Also, do not forget to sign the document.

- Serve the response to the claimant and record the date when the claimant receives the response.

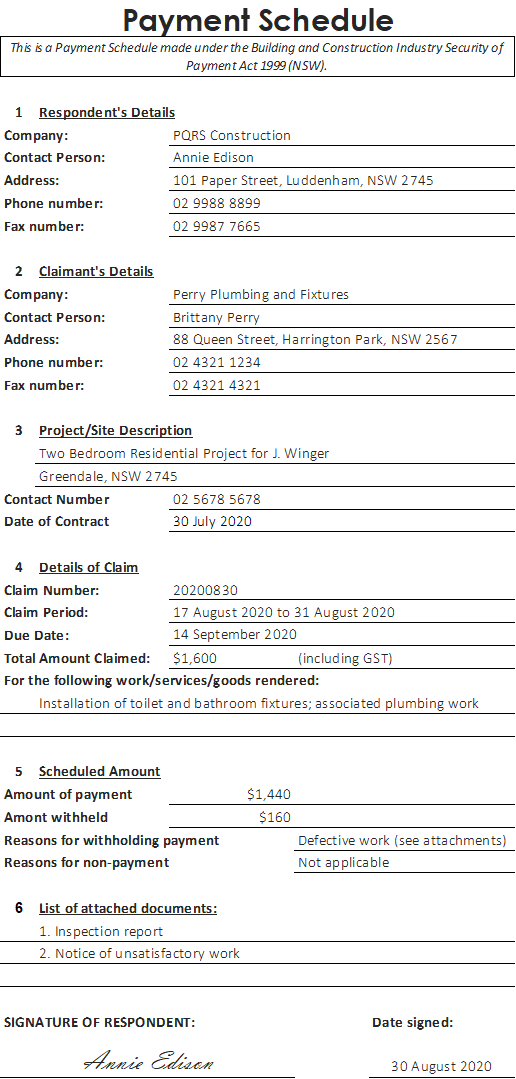

Case Study: A payment schedule issued in response to a subcontractor’s claim

Annie Edison, who works for PQRS Construction, was appointed to oversee the construction of a residential project in Greendale, NSW. After the completion of the plumbing work in one of the bathrooms, she received a payment claim that amounted to $1,600 from Perry Plumbing Works (represented by Brittany Perry), the plumbing subcontractor for the project.

For this project, the contract between PQRS Construction and Perry Plumbing Works State that:

- The scope of work assigned to Perry Plumbing Works include the supply and installation of all plumbing in the building, including those in all bathrooms, in the kitchen, and the exterior of the house.

- For any defective work performed by Perry Plumbing Works, PQRS Construction can withhold up to 5% of a progress payment on top of the retained amount until the defect has been rectified.

After a routine inspection, a number of pipes installed in the bathroom were found to be defective and needed to be replaced. Annie noted this in the payment schedule and indicated that $160, the equivalent of 5% of the amount claimed, would be withheld.

Annie filled out all important claimant and respondent details, details of the claim to which the payment schedule was addressed, and details of the project. She also checked the legislation for the prescribed timeframe and confirmed the response and payment deadlines.

Annie also attached documents that supported the payment schedule and signed the document after completing the details.

She served the payment schedule to Brittany Perry, the representative of Perry Plumbing Works. Afterward, Annie recorded the date.

Consequences of failing to pay undisputed amount

In general, when a respondent fails to make payment by the due date or in accordance with the issued payment schedule or notice of dispute, the claimant becomes entitled to the following:

- Recover unpaid portion of claimed amount as a debt due in court

- Make an adjudication application

- Serve notice on the respondent of the claimant’s intention to suspend carrying out construction work or supply goods and services

- Exercise a lien over any unfixed plant or materials (i.e. keep the respondent’s assets in the form of plant or materials until the respondent is able to pay the amount owed)

Invoices

Apart from payment claims and payment schedules, parties engaged in construction also issue invoices to document transactions. Designing Buildings define an invoice as:

‘a document issued by a vendor to a purchaser, setting out the products or services that they have purchased (or have agreed to purchase) and the amount that is payable. Invoices can be sent before or after the delivery of products or services, and typically include a payment due date. An invoice can also be sent after a purchase order has been agreed.’

Invoice vs. payment claim

With this definition, you may notice that invoices are very similar to payment claims — both documents are formal requests for payments for goods or services rendered. In general, Australian laws allow a document to serve as both a payment claim and an invoice on the condition that it fulfills all legal requirements for a payment claim and for an invoice. However, it is important to note that not all invoices are payment claims and not all payment claims are invoices.

In the previously discussed case study of a payment claim issued by a subcontractor, you may recall that an invoice was attached with the payment claim and is therefore a separate document serving a distinct purpose.

Tax invoice

Invoices in construction mostly pertain to tax invoices. By law, a tax invoice is needed for the claims amounting to more than $82.50 including Goods and Services Tax (GST).

Tax invoices must include the following information:

- a statement that the document is intended to be a tax invoice

- the issuing party’s identity (name of organisation and representative)

- the issuing party’s Australian business number (ABN)

- the date the invoice was issued

- a brief description of the goods or services for which the invoice was issued (include quantities if applicable and indicate the price)

- the GST amount payable (may be separate or included in the total price)

- the payer’s identity and ABN (for invoices over $1000)

Recipient-created tax invoice (RCTI)

In construction project transactions, it is common for a payer/respondent to write a recipient-created tax invoice (RCTI) after receiving a payment claim. An RCTI is often attached with the payment schedule and reflects the scheduled amount.

A respondent may issue an RCTI if the contract allows it or if the respondent has a separate written agreement with the claimant stating that the respondent may issue an RCTI and the claimant will not issue a tax invoice. A template for RCTIs has been provided by the Australian Taxation Office here.

Issuing an invoice

As a supervisor, you may be assigned to issue or authorise issuance of invoices to clients or RCTIs to subcontractors and suppliers. It is therefore important that you understand the process of issuing invoices.

To issue an invoice, you (or an authorised person must):

Determine the type of invoice needed.

Organisations registered for GST are required to issue official tax invoices. Organisations registered for GST are those with a GST turnover (i.e. gross income minus GST) of $75,000 or more. Organisations that are not registered for GST must issue regular invoices stating that no GST was charged or showing that the GST amount is zero. Most organisations engaged in construction, especially contractors, are registered for GST and must therefore issue tax invoices.

Use your organisation’s standard invoice layout.

Use your organisation’s standard invoicing layout or template. Not only will this help the other party to immediately identify that a particular invoice is from your company, but it will also help them immediately identify important information especially on repeat transactions.

Make sure the invoice covers the required information.

Check whether the invoice includes the required details for tax invoice (label indicating that the document is a tax invoice, details of your organisation, date of issue, description of goods and services, the GST amount payable, and the details of the other party when payable amount is more than $1,000.

Make sure all details indicated in the invoice are correct and up to date.

Check whether the items indicated in the invoice and the corresponding amount are correct. Check computations for any discounts, deductions, or additional charges applied. Check if the invoice matches the relevant documents (e.g. purchase order, payment claims, payment schedule, etc.) and verify any discrepancies. Make sure the total payable amount is correct.

Send the invoice promptly and securely.

Avoid delays in payment processing by sending the invoice on time. Also, make sure that the payer receives the invoice by sending the invoice using secure modes. You may opt to send invoices via email whenever applicable, as emails encourage fast response and reduce the risk of losing the invoice.

Keep a record of the invoice.

The law requires business organisations to keep business records for at least five years. Properly file all other invoices of payments you have received or payments that you have made or authorised. As much as possible, make electronic copies of these invoices for backup.

Payment of material and subcontract invoices

As a supervisor, you are also expected to monitor transactions with suppliers, subcontractors, and clients. Aside from issuing invoices, you will also have to authorise payment of invoices issued by the supplier or the subcontractor. Moreover, you will also have to validate payments made by the client in response to claims and invoices issued by the contractor.

Payment of invoices for materials supplied

Generally, the supply of materials involves the following steps:

Before payment can be made to the supplier, it must first be approved by authorised personnel. Usually, the go signal for payments is given by the procurement manager or the project manager. However, the supervisor may also be appointed to authorise payments, especially for material deliveries on site.

To authorise payment of invoices for supplied materials, you must do the following:

|

|

Compare the list of delivered materials with the purchase order (PO). The PO serves as the official order document issued by the contractor to the supplier. Make sure the supplied materials have the correct quantities and specifications based on the PO. |

|

|

Inspect the quality of materials. Make sure that supplied materials arrived in good condition. Sometimes, the supplier will even ask authorised personnel from the contractor’s side to sign a document stating that materials were received in good condition. Therefore, you must inspect the materials and mention and put forward any defect immediately. |

|

|

Check the invoice. Make sure you pay for the correct unit price and total price. Make sure proper deductions have been accounted for (e.g. when discounts are given, when down payment has been made previously or when issues that warrant you to withhold payment arise). |

|

|

Approve payment to supplier. When the supplied materials follow the purchase order and are clear of defects, and all issues relevant to the supplied materials are resolved, then you can give the go signal for payment to proceed. |

|

|

Sign necessary documents and ask for payment receipt. Once payment has been made, you must ask for the receipt of payment. You may also have to sign documents that verify the payment. Do not forget to file these documents properly. Also, record the mode of payment (cash, cheque, electronic) and relevant details (check number, who signed the cheque, etc.) |

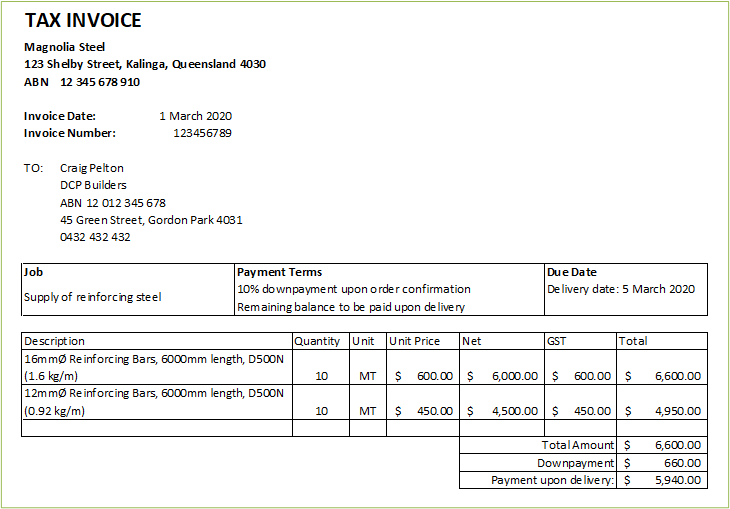

Case Study: Invoice from a supplier

Craig Pelton was assigned to manage the construction of a residential project for a growing builder, DCP Builders in Queensland. After the purchase order for steel reinforcements have been finalised, Craig sent the order to Magnolia Steel, the supplier. Magnolia Steel required 10% down payment upon confirmation of order, to which DCP Builders complied. After forwarding the order to Magnolia Steel and issuing the required down payment, Craig received the following invoice from the supplier:

When the materials were delivered three days after placing the order, Craig checked the delivery documents and compared it with the purchase order. He determined that the materials delivered match the purchase order initially submitted to the supplier. He also inspected the materials upon delivery and confirmed that there were no defects. He also reviewed the invoice to make sure that he will be paying the right amount. As there were no issues with the supply of materials, he paid the remaining balance and asked for a copy of the receipt, which he filed and recorded appropriately.

Payment of invoices for subcontracted work

The contract between a contractor and a subcontractor defines the scope of work for which the subcontractor is hired as well as the obligations of each party with regard to payment. This contract would also indicate the dates and conditions when the subcontractor can expect to receive the payment. Instead of a purchase order, the basis of payment for subcontracted work will be the provisions of this contract. All payments to subcontractors must be approved by authorised personnel (project manager, supervisor, etc.).

To authorise payment of invoices for supplied materials, you must:

Review the contract.

Check the schedule of work and corresponding amounts of payment. Make sure that the payment is in line with the provisions of the contract. Take note of any variations in contracted work integrated in the payment.

Check the invoice, payment claim, and payment schedule relevant to the payment.

Make sure that the payment (amount, date of payment) matches with what is indicated in the payment claim, invoice, or payment schedule for which it is issued.

Check the inspection report.

Make sure that the subcontractor has satisfactorily completed the work associated with the payment. Payments may be withheld for defective work depending on the contract provisions.

Approve payment to subcontractor.

When it has been verified that the subcontracted work has been completed accordingly and relevant issues have been resolved, then you may allow the payment to proceed.

Sign necessary documents and ask for payment receipt.

Once the payment has been made, you must ask for the receipt of payment and sign any verifying documents. In some cases, you may also have to forward these documents to the project manager for them to sign. Do not forget to keep and file these documents properly. Also, record the mode of payment and relevant details.

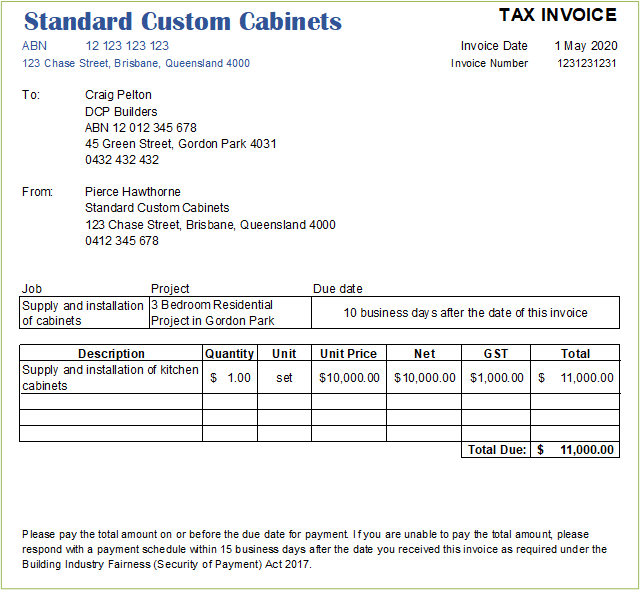

Case Study: Invoice from a subcontractor

After the subcontractor for building and fixing cabinets, Standard Custom Cabinets, were finished with working on the kitchen cabinets, their representative issued the invoice on the next page to DCP Builders. As you may notice, this invoice addressed the requirements for an invoice and for a payment claim, therefore it served both purposes.

Upon reviewing the contract, Craig Pelton (who managed the construction project from DCP Builders) noted that this payment claim is aligned with the provisions of the contract. Since the invoice serves as the payment claim, and no other payment claim was previously issued in relation to the work described, Craig checked if there are any grounds for disputing this claim in order to serve a proper response (payment of the full amount or payment schedule). He checked the inspection records to see if there is any defect in the installed kitchen cabinets that need rectification. Upon reviewing the latest inspection report, Craig found that the installation of the kitchen cabinets was indeed properly completed. Therefore, he concluded that DCP Builders must respond with a payment.

After five days, Craig proceeded to issue a cheque to the subcontractor equivalent to the amount in the invoice. He recorded the cheque number and asked the subcontractor’s representative, Pierce Hawthorne, for a payment receipt. Afterward, Craig filed the receipt accordingly.

Receiving payments from clients

As a supervisor, you will not only need to monitor the payments made by your organisation to a supplier or a subcontractor, but you will also need to be aware of the payments made by the client to your organisation. The record of payments made by the client to the subcontractor must tally, and therefore, proper monitoring and recording of payment will help your case should disputes arise.

In general, the contractor must authorise a person or a few people from their team to receive and certify payment from the client. Usually, this task is appointed to the project manager or someone in the higher management. In some cases, the supervisor may also be authorised to receive payment from the client.

As a supervisor, it is always best for you to exercise caution and inform the project manager first before receiving payment from the client.

Drawing against allowances

In most construction contracts, particularly in housing contracts, final contract sums may differ from the initial contract sum due to additional costs in work and material. To minimise cost overruns, construction contracts will have provisions for Prime Cost (PC) items and Provisional Sums (PS) items, which are essentially allowances to cover the additional costs. These items are, in general, allowances for additional costs in material and work.

What are prime cost (pc) items?

Prime Cost (PC) items refer to items in the contract, (specifically, supplied materials) for which an agreed estimated amount is temporarily set. PC items are items that are usually purchased and selected at a later stage in the construction (e.g. tiles, taps, doors, vanities, etc.). As these items are subject to the client’s choice, the prices considered may inevitably change.

For example, when a client opts for an item beyond the range specified by the PC item, e.g. a $500 door instead of a $400 PC amount, a variation will then be required to cover the additional $100 on the contract price, plus an additional percentage of overhead. On the other hand, if the client opts for a door that costs lower than the PC, say a $350 door, the contract price will be reduced by $50 and there will be no adjustments for overheads. Every change in amount of the PC item will consequently result in the change of contract amount.

What are provisional sum (PS) items?

Provisional Sum (PS) items are intended to serve as allowances to cover work and/or materials that are still unknown at the time the contractor and the client enter a contract. The contractor will usually include PS items for site work costs and for work where exact quantities may be hard to determine (e.g. excavation, projects in the preliminary/conceptual design stage, etc.). As with the PC items, any excess in the PS items will be added to the contract sum.

For example, a building site may initially seem clean, and minimal sitework is expected. However, during the actual excavation, there may be large debris, wood or rocks concealed below the surface that will make the excavation more difficult. Consequently, this will add to the contract price.

As with the PC items, any excess or reduction in the price of a PS item will reflect as an adjustment to the contract amount.

Back charges

A back charge is a mechanism in a construction contract that allows the hiring party to charge the hired party (i.e. the client to charge the contractor or the contractor to charge subcontractor) for defects and damages resulting from the hired party’s work.

Back-charges may be charged for the following reasons:

- Defective work or materials

- Damage to a jobsite

- Clean-up

- Equipment rental

To further understand back charges, take a look at this example:

Case study: Subcontractor leaves the building untidy after repair work

During the final stages of construction, it was found that one of the interior walls in a construction project was improperly installed and was missing a few components. The fit-out subcontractor was called back to complete their work after the building has already been cleaned and prepared for handover. In rectifying the work in the interior wall, the fit-out subcontractor leaves the building untidy and disorganised.

Upon seeing the situation, the contractor sees two ways to fix this:

- The subcontractor can clean the house to the standard that it was before they carried out their work, or

- The contractor will charge the subcontractor for the cost of the cleaners to go back in and clean the building again.

The second option is what constitutes a back-charge. The contractor will charge the subcontractor the cost for cleaning the mess that they left. This back-charge may be covered in two ways: it could be subtracted from the final payment to the subcontractor, or it could be a direct charge to the subcontractor.

Before the contractor proceeds with a resolution, however, they must first notify the subcontractor about the problem. If the subcontractor does not rectify the problem, then the contractor may proceed with calling in the cleaners and charging the subcontractor for the cost.

Back-charges can be complicated; therefore, it is important to properly communicate issues that warrant back-charges. In the example above, it was mentioned that the subcontractor must be notified of the problem first. It is always a good practice to issue a notice to the concerned party before back charging. Notices of defective work must cover important details regarding the problem so that the concerned party can immediately take action. The concerned party must be given enough time to respond to the notice and rectify any issues caused by their work.

Aside from proper communication, all activities related to back-charges must also be properly recorded so that proof to support or contest the back-charge will be available when needed.

Before authorising back-charges, you will have to again, review the provisions of the contract, the notice of defect, and when available, the inspection report.

Construction is a complex process that often requires changes and adjustments to be made along the way, particularly in methodology and consequently, in administration. Such changes and adjustments are usually expected on construction projects that began before design was finalised. However, projects commencing after the final design is completed are not necessarily exempted from having changes and adjustments. Frequently, variations in the construction contract happen regardless of how complete the design is at the beginning of the project.

For the most part, these variations will be covered in the contractor’s estimates and applied contingencies. However, there will also be cases when the adjustments go beyond the estimated budget and will ultimately be an additional cost. In either case, these changes must be properly communicated between all parties involved and must be properly documented.

As a supervisor, you will have to properly administer variations to contracts on site. Therefore, it is important to be familiar with variations and how they affect the contract and the construction work on site.

Variations to contracts

Variations

A variation, also referred to as a variation order or change order, is any change in the original scope of work initially stipulated in a construction contract. Variations may be an addition, substitution, or omission from the initial work specified.

As mentioned previously, it is common for construction projects to incur variations and deviate from the original design and specifications. These variations may be caused by several factors, including technological advancement, changes in regulations, changes in site conditions, non-availability of specified materials, or plainly due to an improvement of the design.

Variations may include changes in the design, quantities, specifications, quality, working conditions, and sequence of work.

Standard forms of contracts usually include provisions for requesting, issuing, and administering variations in the contract. Standard forms of contract also often specify other conditions that may also be considered as a variation.

Effects of latent conditions

Some standard forms of contract deem the effect of latent conditions as a form of variation (e.g. AS 4000, AS 4902). Latent conditions refer to the conditions on the site or near the site that could not have been anticipated by the contractor through reasonable observation or investigation at the time of tendering.

Examples of potential latent conditions include:

- hazardous materials (e.g. asbestos)

- soil contamination

- subsurface conditions (e.g. presence of rocks and hard debris below ground, sinkholes, etc.)

- underground utilities and concealed building services

- other physical site conditions that are not easily observable

In such cases where the effects of latent conditions are considered variations, it may be best to file the associated works as variations. This will ultimately depend on the provisions of the contract however, and therefore it is important to meticulously review the contract.

Issuing and responding to variation orders

Variations may either be initiated by the contractor or the client. For example, the contractor may encounter difficulty in sourcing the material specified by the client and may therefore ask the client if they would allow the use of a different but acceptable material. On the other hand, the client may opt to change parts of the building design and may issue a variation order to the contractor.

In both cases, there is one critical condition: the planned variation must be made known to and approved by the client. Additionally, variations must also be properly communicated and recorded to avoid disputes.

The QBCC Act requires the contractor to present the variation to the client in writing, regardless of who initiates the variation. Moreover, the variation document also complies with the QBCC Act if it:

- is readily legible

- describes the variation

- states the date of the request for the variation

- states the building contractor’s reasonable estimate for the period of delay (if the variation will result in a delay affecting construction work)

- states the change to the contract price (or method of calculating the change in contract price) because of the variation

- states when the increase is to be paid (if the variation results in an increase in the contract price)

- states when the decrease is to be accounted for (if the variation results in a decrease in the contract price)

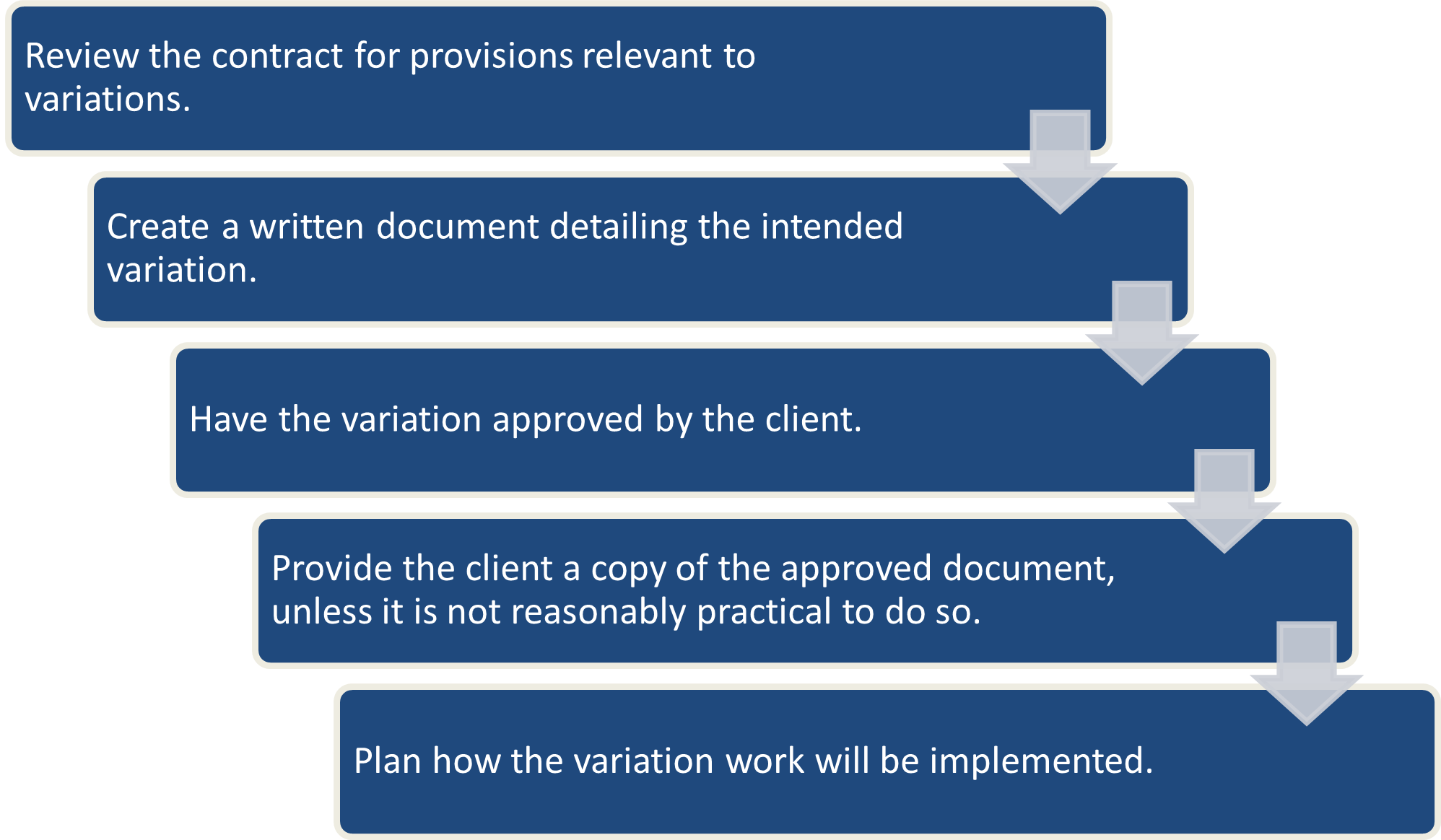

In general, the contractor must follow the following procedures before proceeding with variation work:

Again, the contractor must make sure that all variations are approved by the client before proceeding with variation work. Moreover, the contractor must ensure that they are on the same page as the client regarding the variations i.e. the contractor and the client must have the same understanding on how these changes will be implemented and how these changes will affect the project cost.

In general, changes in the project cost due to these variations must be well documented and integrated into the contract. It is important to note, however, that the contractor cannot require payment for a variation before the variation work is started. For claims involving variations, it is always best to check the contract provisions.

To further understand variations in construction, consider the following case study.

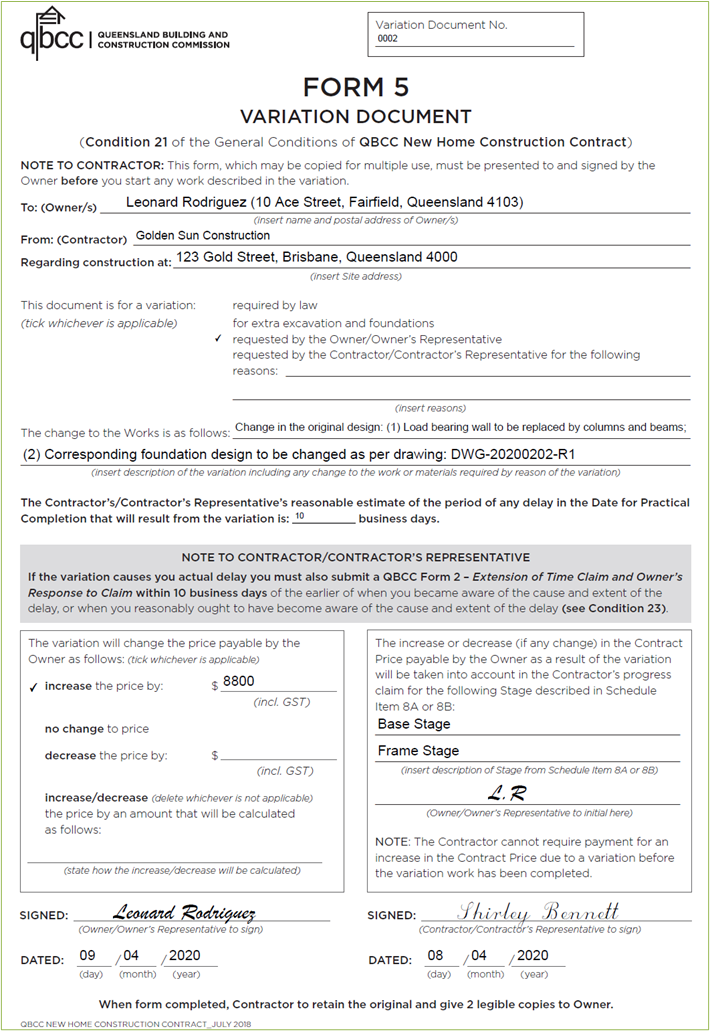

Case Study: Variation initiated by the client

Shirley Bennett was put in charge of the construction work for a three-bedroom, single storey residential project on behalf of Golden Sun Construction. A few days after the work for the base stage began, the client decided to change the layout of the house and open up the living room space.

The client wanted to remove the load bearing wall between the living room and the kitchen and replace it with appropriate columns and additional beams. This also prompted change in the corresponding foundation design. After finalising his decision, the client issued a variation order to Golden Sun Construction.

Knowing that this variation would change the quantities and the timeframe initially considered, Shirley immediately consulted with the planning and estimating team to determine the delays and additional costs that this variation would cause.

Afterward, Shirley immediately prepared the variation document. She indicated the details of the variation, the additional cost, and the delay. She also filled out details relevant to the project (e.g. project site, client details, and contractor details). After completing the variation form, she sent it to the client and got it back the next day with the client’s approval.

After getting the variation document back from the client, Shirley made two (2) copies, filed the original, and gave the client two copies, as required. The completed variation form can be found on the next page. Notice that despite the variation being initiated by the client, the contractor was still required to issue a variation documentation and have it signed by the client before proceeding with the variation work. Moreover, the contractor also provided the client copies of the variation document.

Extension of time requests

Delays and adjustments with the schedule are common in construction projects. Allowances for likely delays (e.g. inclement weather, holidays, etc.) are usually integrated in the project schedule during the planning stage. However, unforeseen delays like those caused by variations and events beyond the contractor’s control will unavoidably extend the construction period. As a result, the practical completion determined in the contract will have to be pushed back at a later date. When this happens, the contractor may be eligible to file an Extension of Time (EOT) request, depending on the provisions of the contract. Note however that EOT requests can only be filed for delays that occur before practical completion.

As a supervisor, you may have to forward EOT requests to the client on behalf of your organisation. Some key points to remember when making EOT requests include:

1. Always review the contract. Before preparing the EOT requests or claims, check the provisions of the contract relevant to EOTs. Make sure the cause of delay is eligible for an extension of time according to the contract.

2. Keep the EOT request or claim concise and include relevant details. Be sure to mention:

- What event caused the delay

- When the event happened

- Documents supporting the request (e.g. referenced variation form, reports, photographs, other records, etc.)

- The number of days of the delay

- The new date for practical completion

When necessary, you may also include the list of affected activities and resources, as well as the plans or actions taken by your organisation to minimise the delay, and the additional costs associated with the delay.

3. Send the EOT requests or claims on time. Make sure that you forward the EOT request as soon as the delay is determined. As time passes after the event occurred, it will be progressively difficult to record the details of the cause of delay.

4. Document EOT forms properly. After the client approves the EOT request, make sure that you file the document appropriately. In some cases, you will also need to provide copies of the approved EOT request to the client.

Consider the following case study of an extension of time claim:

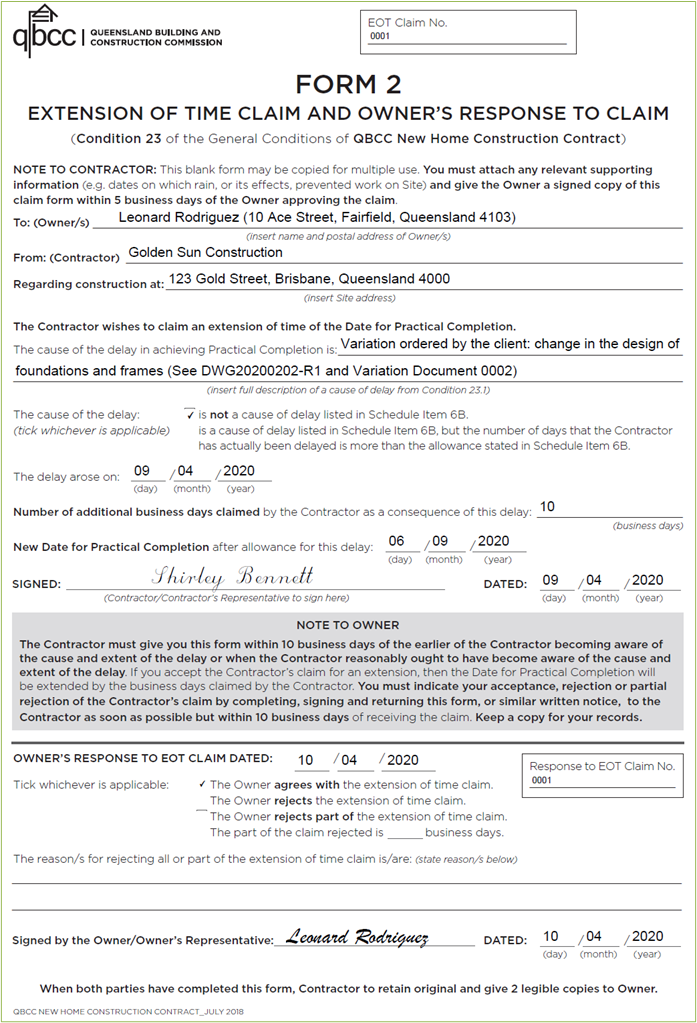

Case Study: Extension of Time claim for delays caused by a variation

In line with the delay caused by the variation ordered by the client, Shirley Bennett prepared an Extension of Time claim.

Shirley stated the cause of delay and gave details on the variation. She mentioned that it is not a cause of delay listed in the contract Schedule Item 6B (Upon reviewing the contract, Shirley found that Schedule Item 6B included likely causes of delay, and this variation is not one of them). Shirley also put the date when the variation has been approved as the day the delay arose. Moreover, she indicated the additional number of business days added to the project schedule, as well as the new target date for practical completion. After signing the document, Shirley sent the EOT claim to the owner, who approved the EOT claim and sent it back to her.

After Shirley received the approval, she made two copies of the document and sent them to the client then she kept the original copy. You will find the completed EOT claim on the next page.

Taking required corrective action

As the person in charge of all site work and activities, it will be up to you as a supervisor to execute work according to an authorised variation.

From our previous discussions, you know that all variations must be authorised by the client or owner. Therefore, before giving the go signal for any related work, make sure that you have received the documents approved by the client. Check that these documents are signed by the client or their authorised representative, and make sure that relevant people are well informed of the planned work or action.

Before proceeding with any action in response to an approved variation, you must first plan how the variation will be efficiently implemented. You must:

- Review the variation. Make sure that you understand the methodology and requirements of the variation work.

- Define the scope of work required by the variation. Does it only require a replacement of the material used? Has the design changed completely?

- Determine how the variation will affect the construction work. Will the variation affect the next work or the nearby work? Will this variation cause delay to other work or on the overall construction work? How will delays or damages be mitigated when executing this variation? Will it be necessary to make an EOT request?

- Identify the relevant people involved. Who will be assigned to work on this variation? Who else will be affected by this variation?

- Take note of the changes in the cost due to this work. Make sure that the changes in the quantities and cost due to the variation work will be reflected in the subsequent payment claims and invoices.

During the implementation of the variation work, make sure to document the process carefully. Take pictures of the variation work and compile relevant progress reports. Keep a record of all communications with the client regarding this variation. Properly keep related invoices and payment receipts. Again, proper documentation will be helpful for you and your organisation should disputes arise over the variation.

An insurance bond acts as a ‘promise’ by the issuing insurance company that they will pay an agreed amount to cover losses due to a specified event.

Before an insurance bond is finalised, the insurance company would usually assess the risks associated with a construction project first and determine the amount of coverage based on these risks. The fees that the insurance company will charge the contractor will also be based on the assessed risks and extent of coverage.

When an event specified in the insurance agreement occurs, the contractor will be eligible to take out the insured amount. But before the insurance company releases the money to cover the losses, the contractor must provide thorough evidence and documentation to support their claim.

Your responsibilities as a supervisor may, in some cases, include processing insurance claims. Therefore, it is important to have a background on the common types of insurances, the losses and conditions covered by insurance, and the process of dealing with insurance claims.

Types of insurances in construction

Below are the common types of insurance in the construction industry.

Construction work insurance

The Construction Work Insurance, otherwise known as the Contract Work insurance, provides a comprehensive protection for the insured party through two main covers: (1) material damage and (2) liability cover.

Material damage

The insurance covers the insured party (e.g. the contractor, client, subcontractors, financiers, etc.) for expenses for replacing or repairing materials that were damaged (by fire, storm, or other similar events) or stolen from the site. The insurance also covers the contractor for expenses incurred from trying to minimise or avoid material damage. For example, when the contractor (in this case, the insured party) hears that a major storm is approaching, they pay for transportation and storage to have the materials removed from the site and stored safely. If the storm still caused damage to the materials despite the mitigation measure taken, the contractor will be eligible to claim the cost for replacing or repairing the damaged materials and for storing the materials away and removing them from the site.

Liability cover

The insurance also provides cover for claims made by the insured party for death, injury, loss or damage to a third party during the construction or a specific period after the construction, i.e. public liability and products liability.

- Public Liability

The insured party is covered for claims made against them by a third party for death, injury, loss, or damage during the time of construction. For example, if during the construction, a debris from the construction site damages the adjacent property, and the owner of the adjacent property makes a claim against the contractor (in this case, the insured party), then the insurance would cover that claim.

- Products Liability

The insured party is also covered for claims made against them for death, injury, loss, or damage that result from a defect in work finished by their organisation for a period after the completion of the project. For example, a few months after the completion of a residential project, the owner discovers that the waterproofing membrane installed by the contractor (in this case, the insured party) was defective and has caused water damage in the house. The owner then files a claim against the contractor, and this claim would be covered by the insurance.

Tools of trade insurance

This insurance policy provides protection for the tools and minor plant used in construction. Some insurance companies would offer this as an additional policy to the Construction Work Insurance or as a separate policy.

Tradies insurance

This type of insurance is especially intended to provide subcontractors and tradesmen with liability cover for damages made against them, as well as to insure their tools and equipment.

Home warranty

This is intended to provide assurance to the owner that they will not be left with an unfinished house in case the contractor (or subcontractor) unexpectedly passes away, disappears, becomes insolvent or fails to respond to a rectification order within 30 days. Usually, the warranty period for this is around five to six years after the completion of work.

Workers’ compensation insurance

This provides cover for workers’ compensation in case any untoward incidents happen while they are at work. This is a mandatory requirement for all employers in Australia.

Income protection insurance

Income protection insurance provides an insured party a fallback in case they suddenly find themselves without an income or unable to work due to illness or injury.

Insurance for legal expenses and costs

This type of insurance policy covers expenses for legal proceedings, which may include legal representation fees, legal advice fees, court attendance fees, and settlement fees.

Apart from the types mentioned, other specific insurance policies for construction work exist. Due to intricacies of every insurance policy, processing a claim may be complicated. Thus, it is crucial to review the insurance policies covering a construction project thoroughly.

Processing insurance claims

Insurance policies in construction are determined based on the risk assessment of the work associated with a project. As such, insurance companies implement rules and procedures to ensure the validity of an insured party’s claim. These rules and procedures can be quite complicated and may vary for every insurance policy. Therefore, it is always best for the insured party or their representative to become familiar with their insurance policy.

As a supervisor managing on site activities, you will be inevitably involved in the processing of insurance claims for incidents that happen on site.

In general, you will be involved in processing insurance claims when incidents happen for which your organisation is eligible to take out an insured amount. To process insurance claims, you must:

- Make sure the incident it is properly documented. Insurance companies require thorough documentation of the incident and the basis of claim. This is to make sure that the incident occurred beyond the insured party’s reasonable control and that the insured party has taken sufficient measures to avoid the incident from occurring. In most cases, insurance companies will initiate their own investigation of the incident; therefore, it is important to be able to provide them with enough evidence to support your case. Take photographs of the incident and make comprehensive reports. Keep all your payment receipts and invoices. For losses due to fire, theft, or vandalism, make sure to file a police report.

- Contact the insurance company immediately. Call the insurance company to give them a brief detail of the event. Ask them about the processes and requirements that may not have been mentioned in the insurance document. Take note of all the required documents, procedures, and deadlines.

- Prepare all necessary documentation. Fill out forms, prepare the reports and complete all documentary evidence and requirements. Make sure that the claim amount is correctly stated in your claim and that the reason for claim is concisely indicated.

- File the insurance claim immediately. Take note of processing time and make sure that you get confirmation from the insurance company that they have received your claim.

- Review the response of the insurance company. Check whether they have approved your claim to the full amount or not. Depending on the company’s response, determine whether you can already take out your claim or file an appeal (for rejected cases).

- When your claim is finally approved, take out the claimed amount and settle your dues. Keep a record of this transaction.

Watch the below video to learn more about insurance in the construction industry.