In this topic, we will cover:

- What is a treaty?

- The story of Te Tiriti o Waitangi

- The Treaty principles – Partnership, protection and participation

- Elements of culture – Symbols, language, norms, values and artefacts

- The role of non-indigenous designers and cultural appropriation.

Throughout our lives we make agreements with others. They can be informal and unwritten (e.g. being friends with someone, going out on date, arranging to meet somewhere for coffee) or they can be more formal and often written (e.g. signing a rental agreement, getting hire purchase, buying a house). What these agreements do is outline the responsibilities and obligations of the relationship between you and the other person or party. You could also call these agreements a contract, compact or even a treaty.

The term ‘treaty’, however, is usually reserved for the agreements that are made between countries or groups of people (e.g. tribes, ethnic groups). Encyclopaedia Britannica defines treaty as:

A binding formal agreement, contract, or other written instrument that establishes obligations between two or more subjects of international law (primarily states and international organizations).

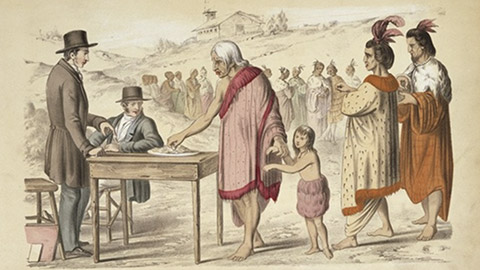

On 6 February 1840, the Treaty of Waitangi (Te Tiriti o Waitangi) was signed at Waitangi in the Bay of Islands by Captain William Hobson, several English residents, and between 43 and 46 Māori rangatira.1

Watch the video below, which explains this in a little more detail.

The treaty governs and ensures both Māori and Pakeha (non-Māori) are protected. New Zealand Immigration explains that it does this by:

- accepting that Māori iwi (tribes) have the right to organise themselves, protect their way of life and to control the resources they own

- requiring the Government to act reasonably and in good faith towards Māori

- making the Government responsible for helping to address grievances

- establishing equality and the principle that all New Zealanders are equal under the law.2

Te Tiriti o Waitangi/The Treaty of Waitangi is an agreement signed by the sovereign independent Māori tribes (iwi) and the representatives of the British Crown. It is considered one of the founding documents of Aotearoa and sets out the obligations and responsibilities of how Māori and the Crown (on behalf of the British settlers) would live together peacefully in Aotearoa.

At the time of the signing of the treaty, the Māori population was around 100,000; the number of settlers was only 2,000.

There has been much written about how Te Tiriti o Waitangi was written, how it was signed, and the subsequent ‘journey’ of the treaty around Aotearoa.

Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand provides a good overview of the story of the Treaty of Waitangi – click on the link and read the story.

For further information, you can read and watch some other resources online at the website of Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand.

From the sources you have just looked at, we know the following facts:

- Te Tiriti o Waitangi was signed on 6 February 1840.

- William Hobson was the Crown representative.

- The missionary Henry Williams, and his son Edward, translated the English draft into Māori.

- More than 40 Māori chiefs signed Te Tiriti/the Treaty at Waitangi.

- Two versions of the Treaty existed: English and Māori.

- The textual differences between the two documents have been a source of much debate and disagreement.

- Breaches of Te Tiriti have led to conflict and the oppression of tangata whenua.

The Treaty principles are sometimes referred to as the three 'Ps'. They are:

- Partnership

- Protection

- Participation.

These principles have different meanings across different industries. In the Health sector, participation could be the medical staff and patient working closely together with the goal of better health; whereas participation in the Education sector could mean Māori whānau involvement in school planning and a reflection of biculturalism of Aotearoa.

Overall, no matter the sector or industry, the principles ensure partnership with engaging Māori communities, participation in decision making and equity for Māori, and the protection of Māori culture, identity, values and tāonga (a measure, thing of importance).

Partnership

'Partnership' acknowledges sovereignty/governance and working together with the same rights and benefits as subjects of the Crown. This principle is about equality and equity between Māori and all other New Zealanders. It is working together at all levels of an organisation and having a say in the policy and management of organisations. It means engaging with Māori in the community when you plan work that affects them.

Protection

The principle of 'protection' acknowledges the protection of rights, benefits and possessions. As well as ensuring equal rights and protecting possessions, it means that Māori tikanga (culture and protocols) and taonga (treasures) such as te reo Māori (Māori language) are respected and given equal footing to the tikanga and taonga of other cultures.3

Participation

'Participation' acknowledges sovereignty and governance--ensuring equal participation at all levels and that Māori have input into decision-making directly affecting them.

'Culture' can be defined as 'the ideas, customs and social behaviours of a particular people or society'. It is worth noting that culture is not defined along geographical or racial lines, it applies to groups of people.

When discussing culture in sociological terms, we often refer to the 'elements of culture'. These elements help us understand more about the context of cultural elements being appropriated.

Symbols

Symbols can be a form of non-verbal communication. They can be placeholders that are intended to represent something else and to evoke emotion by association.

Religions often have a wide variety of symbols that have specific meanings; for example, the crucifix and the Star of David. Other cultural symbols include the yin and yang symbol. Symbols do not have to be physical or written. The act of shaking hands in many cultures is a symbol of politeness in greetings. Holding hands can show a loved one (and the people around you) your feelings. Giving a 'thumbs up' is another example of a cultural symbol.

Māori symbols hold value and meaning. Being aware of these symbols and the significance they hold will allow you to identify where they could be inappropriately used or respectfully incorporated in UX design.

Mountain Jade, a family-run business made up of crafters and carvers, explains that there are six popular symbols that are used. Each symbol’s meaning will vary slightly depending on where it is represented. For example, if a symbol was used in a carving, it may have a slightly different meaning than a tāmoko (tattoo art).

The koru

The koru represents new beginnings, growth and regeneration in pounamu (greenstone) carving. In tā moko (tattooing), the koru represents parenthood, genealogy and ancestry.

The pikorua (twist)

The pikorua is said to represent the path of life and be a symbol of the strong bond between two loved ones. This is seen as a relatively new symbol that has been created due to the evolution of tools for complex undercuts.

The toki (adze)

This design was initially used as a tool. The blade was used to cut down trees, for carvings and for chiefs in the tribe among other uses.

Nowadays, this design is worn around the neck and symbolises strength.

The manaia

The manaia represents a guardian against evil.

The tiki (hei tiki)

The tiki symbol is said to represent Tiki, the first man in Māori myth. Originally this symbol belonged to and was passed down through the generations of one family. This meant that its main function was to connect deceased family members to the living by being worn as a sign of remembrance.

Today, people use this symbol as a form of expression of identity.

The matau (fishhook)

Māori had/have a very strong connection to Tangaroa – god of the sea. This fishhook was a symbol of prosperity and safe travel over water. They were dependent on the abundance of food the sea provided and with that abundance, they flourished.

According to Māori history, Maui used the hook made from the jawbone of his ancestor Mauri-rangi-whenua, to land the great fish that became Te Ika a Maui, the North Island of New Zealand.

Language

Languages, both written and spoken, are some of the most significant ways culture is shared and passed on. A shared language is essential to the development and evolution of a culture.

Language does not have to mean the dominant language spoken or signed in a particular country (e.g. English, Māori or French). It can also refer to the colloquialisms found within a culture.

While English is the predominant language spoken in New Zealand, Māori and New Zealand Sign Language are afforded special protection and recognition as the two official languages in Aotearoa New Zealand. These were established by the Māori Language Act 1987 and the New Zealand Sign Language Act 2006.

The Māori language is considered a national taonga (treasure) and is undergoing a revival. Initiatives such as:

- te Wiki o te Reo Māori (Māori Language Week)

- kura kaupapa Māori (state schools where the teaching is in Te Reo Māori)

- broadcasting in te reo Māori on Whakaata Māori, Māori Television and Te Reo channel

all play a role in making sure Te Reo remains a living language embraced throughout New Zealand.

You can help support Te Reo Māori by making an effort to use correct pronunciation and using simple words and phrases in everyday conversation.4 Te Aka (Māori Dictionary) is a great resource and includes recordings of words so you can check pronunciation.

Norms

Norms are the standards and expectations of behaviour--it is how people within a culture expect others to behave in different situations.

These expectations can be formal, such as laws and codes that are enforced; or informal customs and standards that, while still considered important, are not enforced.

Tikanga is the Māori concept of behaving in a way that is correct. It is a customary system of values and practices that have developed over time and are deeply embedded in New Zealand’s social context.

Different cultures have different norms and it is important to be mindful of this. In many western cultures, eye contact while speaking is considered an act of respect; while in some Pacific cultures, direct eye contact can be regarded as disrespectful.

Values

Every culture has values. They help members judge what is right or wrong, good or bad, desirable or undesirable. The values help to shape the norms.

In many western cultures, individualism is highly valued. 'Become independent', 'standing on your own two feet', 'looking out for number one' are examples of phrases that might have a positive meaning in these cultures.

Other cultures value the collective, the community and the family higher than the individual. You might see extended families living together with younger members taking more responsibility for their siblings and multi-generational households.

Attitudes toward work, education and the environment are all influenced by cultural values.

Artefacts

Artefacts are physical objects that have significance to a culture. We often think about artefacts in relation to ancient civilisations. We imagine archaeologists digging them out of the ground in places like Egypt.

All cultures have artefacts. The carvings that adorn a marae (front of a meeting house), or the pounamu taonga gifted to Iwi/tribe members, and photos or paintings of ancestors are all examples of artefacts.

"Non-indigenous designers need to understand their role as an ally and partner in design initiatives where indigenous context, knowledge or forms are core to the outcome, and to consider ways to avoid holding spaces where indigenous designers could be." 5

Indigenous Design and Innovation Aotearoa (IDIA) has created a framework called Culture Centred Design (CCD). The framework ensures that design ‘outcomes are led, framed and informed by indigenous people, knowledge and ways of being’ (Barbarich et al. 2017). The three strands that form the CCD are tāngata (people), mātauranga (knowledge), and tikanga (process and practice).

IDIA has also created a Cultural Integrity Scorecard of 12 yes or no questions assessing indigeneity, design, integrity and authenticity. Designers are encouraged to use this scorecard to evaluate appropriation and cultural awareness.

If your intellectual property includes Māori elements, your application may be referred to a Māori Advisory Committee.

Getting it wrong

Over the years, there have been many examples of cultural appropriation; as will be seen in the examples below.

- In 2019, Air New Zealand attempted to trademark their masthead 'Kia Ora'. While Air New Zealand uses Te Reo Māori in its branding, they refused to hire a person with tā moko. The Trade Mark application was challenged with many Māori voices calling it a disgraceful act of cultural appropriation and the application was subsequently withdrawn as a result of the public outcry.

- Kapiti Cheese named a cheddar after a famous Māori ancestor, Tuteremoana. The naming and personification was disrespectful and caused hurt to descendants of Tuteremoana, with children worried they would be eating their ancestor.

- Titoki Whiskey bottles represent the god of fertility, Tiki. Titoki claims to be a traditional Māori alcohol, using traditional medicines that were used by ancient spirits but European colonisers introduced alcohol to New Zealand. There was no traditional alcohol before their arrival.

- In 2020, a Christchurch art gallery apologised and removed controversial artwork after complaints of cultural appropriation of Māori culture--the painting by artist Rhonye McIlroy featured a white woman with a moko kauae, bare-breasted and wearing bondage. Facial tāmoko is very tapu (sacred) and the painting exploited, sexualised it, and used it in a derogatory way.

Using or trivialising sacred artefacts and symbols in ways that do not honour or respect them to the same extent that would be expected within their own culture is a sign of cultural appropriation.

Getting tāmoko is a meaningful, cultural event. In contrast to the above examples of cultural appropriation, watch the following video which shows the significance tāmoko has to Māori.

Implications of the Treaty in UX

Identify one way the Treaty could be implicated with a UX design.

In the forum, share your response and provide one example of how this can be avoided.