As the term "exercise science" suggests, there is a wealth of knowledge and research behind the art of choosing the right exercises and their optimal order to achieve fitness goals safely and effectively.

Understanding muscle physiology and movement is essential in exercise selection, which, in turn, is vital to creating functional programs that align with the fundamental principles of training.

- To achieve specificity, you need to select exercises that target the specific muscles and movements required to achieve fitness goals.

- Individualisation is crucial in creating programmes that consider your client’s unique physical attributes. By selecting exercises that account for these individual differences, you can create safe and effective programmes.

- Progressive overload promotes adaptation. To create progressive overload, you need to select exercises that challenge muscles and increase the difficulty over time. This can include increasing weight, reps, sets or shortening the rest period.

- Variety is essential to avoid plateauing and to prevent boredom. Periodically changing the exercises in a programme can help fast-track the client's progress as well as keep them interested and engaged.

It’s also important to think about the order exercises are programmed, as this can make a significant difference in results and safety. Large before small provides a framework for this.

In this topic, we focus on exercise selection within programme design. You will learn about:

- Muscle contraction

- Muscle roles

- Compound and isolation exercises

- Open and closed kinetic chain exercises

- Primal movement patterns

- Large before small

If you need a refresher of training principles or exercises, jump into Exercise Prescription A at any time.

Anatomical terminology

We’ll be using anatomical terminology when discussing exercise prescription and exercise selection. Before we jump into exercise selection check how much anatomy and physiology you recall.

Anatomical direction

Movement terms

Being confident using movement terms lets you explain exactly what happens at the joint during movement and exercise.

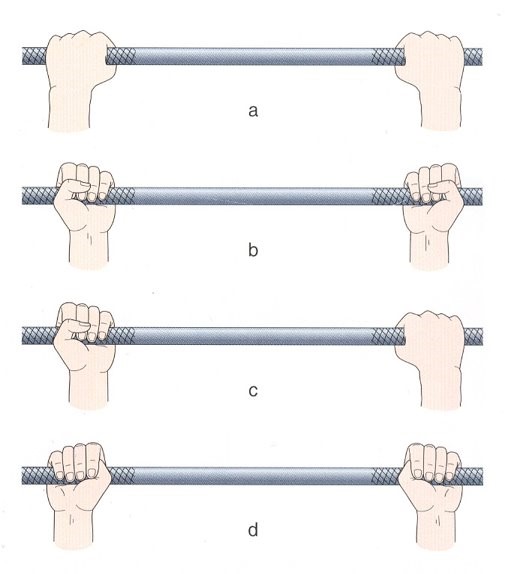

We can use these terms to describe what is happening in an exercise and to be specific about variations. E.g., grip types on barbells can be:

- Pronated (fig. a)

- Supinated (fig. b)

- Alternated (fig. c)

- Hook grip (thumb under fingers) (fig. d)

A solid understanding of muscle contractions and how they relate to exercise will help you design more effective and safe exercise programmes for your clients.

You’ll be able to:

- Create personalised programmes that target specific muscle groups and fitness goals by incorporating different types of contractions to maximise muscle activation.

- Adjust exercise intensity and volume to elicit different types of muscle contractions and achieve specific training adaptations.

- Identify and correct muscle imbalances.

- Prevent injuries by designing workouts that minimise the risk of injury. E.g., avoiding too much eccentric loading too soon to help prevent muscle soreness and injury.

So, what are the types of muscle contraction?

Isotonic contraction

Isotonic contraction is when tension is developed in the muscle while it either shortens or lengthens. Isotonic contractions can be classified as either concentric or eccentric.

- Concentric contraction is when the muscle develops tension as it shortens, and the muscle develops enough force to overcome resistance.

- Eccentric contraction is when the muscle lengthens under load or tension. It occurs when the muscle gradually lessens its tension to control descent of weight.

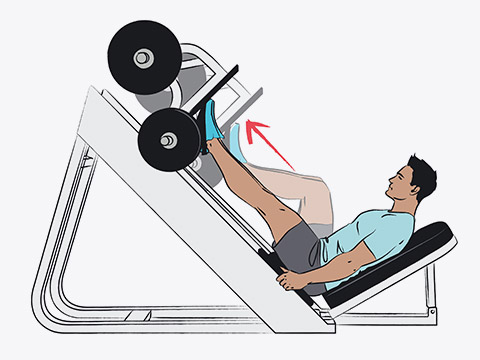

Case study: Leg press

During a leg press, the quadriceps and gluteus maximus muscles are primarily responsible for producing the force needed to lift the weight. The hamstrings and calf muscles also contribute to the movement to some extent.

During the upward phase of the leg press, the quadriceps and gluteus maximus muscles contract concentrically to extend the knee and hip joints, lifting the weight against the resistance.

During the downward phase of the leg press, the quadriceps and gluteus maximus muscles contract eccentrically to control the descent of the weight. This contraction helps slow the movement and prevent any sudden impact on the joints.

Concentric and eccentric phase

Concentric and eccentric can also be used to describe the phase of a movement. The concentric phase is when the movement is overcoming load or resistance (including gravity). The eccentric phase is when the movement is resisting load or resistance (PT Direct, Muscle Roles and Contraction Types, n.d.).

Isometric contraction

Isometric contraction is when the muscle contracts or tension is developed within the muscle but no movement or change in joint angle occurs. The muscle does not shorten or lengthen and little or no movement occurs. I.e., the force developed by the muscle is equal to that of the resistance.

Some common isometric exercises you may do with your clients include the plank, wall sit, and dead hang. Smaller muscles (like the rotator cuff) contract isometrically during an isotonic exercise to keep the movement safe and effective.

Understanding the roles and contractions of skeletal muscles is vital to designing programmes that are specific to your client’s goals and abilities – as well as helps ensure good technique and safety.

Even during a basic movement like walking or squatting, many different muscles contribute to making the movement smooth and effective. Each muscle involved performs an appropriate type of contraction and has its own clearly defined role during the movement.

The 4 defined roles muscles take on during a movement are agonist, antagonist, synergist, and fixator.

| Role | Definition |

|---|---|

| Agonist | Agonist muscles cause a movement to occur through their own contraction. They are the prime mover for an exercise. E.g., the agonist of the bench press is the pectoral group. |

| Antagonist | Antagonist muscles are the opposite muscle group to the agonist. The antagonist typically relaxes, so it doesn’t prevent the agonist moving. At other times, it is actively working to slow down or stop a movement and may contract. E.g., the antagonist muscle group for the barbell curl is the triceps group. |

| Synergist | Synergist muscles assist the prime mover in an exercise. E.g., the synergists for the bench press are the triceps and the anterior deltoid. Not all exercises will have synergist muscles assisting the agonist. If an exercise is an isolation exercise, then it only targets one muscle group. |

| Fixator | Fixator muscles stabilise the body during an exercise to help the agonist function most effectively. E.g., the erector spinae are the fixators for the T-bar row. |

Let's look at the roles of the muscles involved in a barbell bench press.

Agonists and antagonists

During a barbell bench press, the pectoralis major (or "pecs") are the agonists. The pecs are responsible for the horizontal adduction of the shoulder joint and the extension of the humerus (upper arm bone) towards the chest.

The latissimus dorsi or "lats" and the rhomboids are the antagonists. They are responsible for retracting the scapula (shoulder blade) and extending the humerus away from the chest.

Synergists and fixators

The synergist muscles are the triceps and anterior deltoids in the barbell bench press. The triceps are responsible for elbow extension, which helps to push the weight up during the bench press. The anterior deltoids are responsible for shoulder flexion, which helps to bring the arms up and forward during the bench press.

The fixator muscle are the core muscles. The core muscles help to stabilise the trunk and maintain proper form during the bench press.

Identify muscle roles

Weights training exercises fall into 2 categories. They can be compound or isolation.

Compound

Compound exercises involve multiple muscle groups and joints working together to perform the movement. These exercises are known for their effectiveness in building strength and increasing muscle mass, as they allow you to lift heavier weights, recruit more muscle fibres, and progress faster.

They are great for overall muscle development, strength and size, and form good foundations for training. Less strain is put on specific areas of the body because you’re engaging more muscles and joints.

Some examples of compound exercises include:

- Squats: targets the lower body, primarily the quadriceps, hamstrings, and glutes.

- Deadlifts: targets the back, hamstrings, glutes, quads, and grip strength.

- Bench press: targets the chest, shoulders, and triceps.

- Pull-ups: targets the back, biceps, and forearms.

What other compound exercises do you know?

It can be easy to forget that compound exercises are working multiple muscle groups at the same time. Take note of which muscles are being worked, including fixators and synergists, to make sure you aren’t overworking stabilising muscles.

Isolation

Isolation exercises, on the other hand, target a single muscle group and involve only one joint. These exercises are useful for developing specific muscles or correcting muscle imbalances. A seated position is preferable to ensure the movement is truly isolated.

Some examples of isolation exercises include:

- Bicep curls: targets the biceps.

- Leg curls: targets the hamstrings.

- Tricep extensions: targets the triceps.

- Lateral raises: targets the shoulders.

Pin-loaded cables and free weights help reduce the risk of injury caused by pattern overload in isolation exercises. Programme variety to avoid only training certain muscles.

Can you name the joint action in these isolation exercises?

Benefits

Both compound and isolation exercises have their benefits and should be included in a well-rounded strength training program. Compound exercises are great for building overall strength and muscle mass, while isolation exercises can help to target specific muscles and correct imbalances. Consider the client’s goals and always design programmes with respect to the principles of specificity and individualisation (Quinn, 2022 and Laker, 2017).

Compound or isolation?

Watch

The following video explains the pros and cons of compound and isolation exercises in a resistance training programme and how to use them to help achieve client goals in strength and performance.

Scenario: Movement in a programme

Here’s a programme that includes a variety exercises. Can you identify the compound and isolation exercises?

Weights - lower

Warm-up: Cycle 15 Calories

Stretches: Dynamic Stretches (Lunge Hug, Side Squats, Walk the dog)

Activation: Glute Bridge with abduction x 10 reps

Potentiation: 10 reps of BB squat with just bar

| Exercise | Rest | Set 1 | Set 2 | Set 3 | Load | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbell back squat | 90s | 10 35kg |

8 40kg |

6 45kg |

Hinge through hips | |

| Bulgarian split squat | 60s | 10 7kg |

10 7kg |

Drive through heels | ||

| Leg press | 10 83kg |

10 83kg |

Soft lock 15kg per side |

|||

| Dumbbell Romanian Dead Lift | 60s | 10 12kg |

10 12kg |

10 12kg |

Keep back flat | |

| Jump squats | 30s | 30s | 30s | 30s | As much height as possible | |

| Dead hang | 40s | 40s | Brace core, feet forward | |||

| Weighted plank | 40s 5kg |

40s 5kg |

Stay square |

Weights - Upper

Warm-up: Rower 500m

Stretches: Dynamic stretches (thread the needle, cat/cow, back pats)

| Exercise | Rest | Set 1 | Set 2 | Set 3 | Load | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbell benchpress | 90s | 6-10 | 6-10 | 20kg | Full ROM | |

| Dumbbell flyes | 12 | 12 | 5kg | Big hug | ||

| Inverted row | 60s | 8 | 8 | Elbows close | ||

| Upright row | 8-10 | 8-10 | 15kg | Lead with elbows | ||

| Curl'n'press | 60s | 10 | 10 | 4kg | Twist through ROM | |

| Dumbbell kicks | 10 | 10 | 3kg | Elbows high | ||

| Medicine ball crunch | 60s | 10/10 | 10/10 | 3kg | Eyes on ceiling | |

| Medicine ball Russian twist | 10 | 10 | 3kg | 45 only | ||

| Medicine ball leg raises | 10 | 10 | 3kg | Shins to ball |

Programme Notes:

This programme is a progression from the full body programme you have been following. It will allow you to dedicate a bit more focus and energy to individual areas.

Ensure you stretch in between sets. Aim to increase the load as you get more accustomed to the movements.

We will change this programme in another 6-weeks' time.

All the bones and muscles in the body are connected in a chain. This chain can be referred to as the kinetic chain. Movements we make, are part of this kinetic chain and can be classified as either open or closed.

Open-chain

Open kinetic chain exercises are exercises where the hands or feet (distal points) are free to move during the movement. These exercises tend to by isolation exercises, isolating a single muscle group or joint. Examples include:

- Leg extensions/leg curls

- Bench press

- Overhead press

- Leg press

- Lat pulldown

Closed-chain

Closed kinetic chain exercises are exercises where the hands or feet are fixed and cannot move during the movement. Generally, it’s the central core (proximal segments) that move. Closed-chain exercises work multiple muscles and joints at the same time, so these are compound exercises. Examples include:

- Squats

- Lunges

- Push-ups

- Pull-ups

Closed-chain exercises are safer for joints because the distal end of the limb is in a constant, fixed position, usually on the ground. This emphasises joint compression and stabilises the joint. A programme that uses a variety of movements and exercises will achieve the best results, but closed-chain exercises should comprise the bulk of the workout (Kennedy, 2018).

Scenario: Movement in a programme

Let’s look at the 2-day split training programme again. This time can you identify the open and closed kinetic chain exercises?

Weights - lower

Warm-up: Cycle 15 Calories

Stretches: Dynamic Stretches (Lunge Hug, Side Squats, Walk the dog)

Activation: Glute Bridge with abduction x 10 reps

Potentiation: 10 reps of BB squat with just bar

| Exercise | Rest | Set 1 | Set 2 | Set 3 | Load | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbell back squat | 90s | 10 35kg |

8 40kg |

6 45kg |

Hinge through hips | |

| Bulgarian split squat | 60s | 10 7kg |

10 7kg |

Drive through heels | ||

| Leg press | 10 83kg |

10 83kg |

Soft lock 15kg per side |

|||

| Dumbbell Romanian Dead Lift | 60s | 10 12kg |

10 12kg |

10 12kg |

Keep back flat | |

| Jump squats | 30s | 30s | 30s | 30s | As much height as possible | |

| Dead hang | 40s | 40s | Brace core, feet forward | |||

| Weighted plank | 40s 5kg |

40s 5kg |

Stay square |

Weights - Upper

Warm-up: Rower 500m

Stretches: Dynamic stretches (thread the needle, cat/cow, back pats)

| Exercise | Rest | Set 1 | Set 2 | Set 3 | Load | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbell benchpress | 90s | 6-10 | 6-10 | 20kg | Full ROM | |

| Dumbbell flyes | 12 | 12 | 5kg | Big hug | ||

| Inverted row | 60s | 8 | 8 | Elbows close | ||

| Upright row | 8-10 | 8-10 | 15kg | Lead with elbows | ||

| Curl'n'press | 60s | 10 | 10 | 4kg | Twist through ROM | |

| Dumbbell kicks | 10 | 10 | 3kg | Elbows high | ||

| Medicine ball crunch | 60s | 10/10 | 10/10 | 3kg | Eyes on ceiling | |

| Medicine ball Russian twist | 10 | 10 | 3kg | 45 only | ||

| Medicine ball leg raises | 10 | 10 | 3kg | Shins to ball |

Programme Notes:

This programme is a progression from the full body programme you have been following. It will allow you to dedicate a bit more focus and energy to individual areas.

Ensure you stretch in between sets. Aim to increase the load as you get more accustomed to the movements.

We will change this programme in another 6-weeks' time.

At this point, you should be feeling pretty comfortable with the concept that programmes need to be individualised and specific. To be effective for general human development, a programme should also be designed based on functional movement patterns rather than focusing solely on isolated muscle groups.

Functional movement

Primal movement patterns are a set of fundamental movements that humans have evolved to perform to survive and thrive. These movements are based on our natural instincts and include fundamental human movements we use daily. The concept of primal movement patterns has become popular in recent years to help people achieve functional fitness.

There are 7 primal movement patterns:

- Squatting

- Lunging

- Pushing

- Pulling

- Hinging

- Twisting

- Gait

Incorporating these primal movement patterns into workout routines can help clients achieve functional fitness, improve overall health, and enhance performance in daily activities and sports.

When we look at primal movement patterns, recall that the human body’s movement is divided up into 3 planes: sagittal (front to back), frontal (side to side), and transverse (rotation). A good training programme will work in all 3 planes and a warm-up should do the same.

Squatting

The squat is a fundamental movement pattern that involves bending at the hips and knees to lower the body towards the ground. This movement is important for daily activities such as sitting down and standing up, as well as for athletic movements like jumping and sprinting.

This is the most complex and compound movement which the body can perform. It is referred to as bilateral, which implies the movement is performed in unison, by limbs on both sides of the body. This movement targets muscles of the lower body such as the glutes, hamstrings, quadriceps along with the core.

Lunging

Lunging involves stepping forward with one foot and bending both knees to lower the body towards the ground. This movement pattern is important for activities such as walking and running, as well as for sports that require changes of direction.

It’s an unstable body movement which sees one foot further forward from the other, requiring greater balance, stability, and flexibility. This movement is referred to as unilateral, implying the limbs move independently of each other to produce the desired movement. Exercises can include step-up and side lunges which target muscles of the lower body such as the glutes, quadriceps, hamstrings along with the core.

Fun fact, due to the stance of the lunge, all the glute muscles are stimulated to a greater degree than in a squat.

Pushing

A push movement can be performed in the horizontal and vertical plane, consisting of pushing a weight away from the body or the body away from a weight. This includes push-ups and shoulder presses.

These exercises target the muscles of the upper body such as the chest, triceps, and anterior shoulders.

Pulling

A pull movement can be performed in the horizontal and vertical plane and is the opposite of a push. Instead, it involves pulling a weight closer towards the body or the hands.

Pulling uses the large muscles of the back and upper body, including the biceps, forearms, lats, rhomboids and posterior shoulders. Examples include seated row, pull up, or horizontal pull.

Hinging

Bending or hip hinging is movement in which the glutes move back and the torso learns forward, maintaining a neutral spine. Hinging is essential for activities such as picking up heavy objects from the ground, deadlifting, and Olympic lifting.

It uses the posterior chain muscle groups, including the hamstrings, glutes, and lower back.

Twisting

Unlike the other primal movements, twisting is not performed in the horizontal or vertical plane nor requires movement forward or back. Instead, this action refers to trunk rotation movement performed within a turning or twisting fashion.

This movement can be seen when throwing or kicking a ball, changing direction whilst running, passing an object as well as others. It is an essential movement in sporting success.

Exercises that replicate this include the Russian twist, med ball twist, and the woodchopper.

It is important to incorporate twisting movements into workouts to maintain overall mobility and function in the spine and core muscles. However, it is worth noting that twisting movements can be more complex than other primal movement patterns and may require additional attention to form and technique to avoid injury.

Gait

This term refers to the technique of walking. This fundamental movement pattern includes a combination of movements such as running, jogging, and jumping.

Gait is essential for getting around and for many sports and activities.

These basic exercise movement patterns are simple exercise classifications, which form the foundations of exercise selection in any program. As a personal trainer, it is important to determine basic movement patterns that are essential for a client and then devise a range of exercises forged from those movement patterns (i.e., exercise classifications).

Scenario: Primal movement patterns in a programme

Here's a full-body programme for Bella. Can you identify which primal movement pattern/s are used for each exercise?

Bella's programme

Warm-up: Assault bike 15 calories

Mobilisation/activation: 5 reps of the following:

- Open the gate

- Cat/cow

- Thread the needle

- Walk the dog

- Glute bridges

| Exercise | Rest | Set 1 | Set 2 | Set 3 | Load | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goblet squat | ss | 15 | 15 | 16kg | Lead with hips | |

| Walking lunge | ss | 12 | 12 | Back knee to floor | ||

| Powerbag hip thrust | 60s | 15 | 15 | 20kg | Squeeze at top | |

| Dumbbell bench press | ss | 8-10 | 8-10 | 7kg | Controlled movement | |

| Ring row | ss | 10 | 10 | Squeeze shoulder blades | ||

| Russian twist | ss | 10 | 10 | Touch toes |

Accountability habits:

- Average 9,000 steps per day

- At least 3 exercise sessions per week

- Aim to keep portion sizes to guidelines

You will see that this is a well-balanced programme with each of the primal patterns featuring at least once.

The rule of thumb for exercise order is to ensure large muscle groups are worked before small muscle groups. This means programming compound exercises before isolated exercises. This is the rule for most programme designs for general population but may need modification in instances such as rehabilitation or bodybuilding.

Why train large before small

Safety is key! Compound exercises involve multiple muscle groups, which play a big part in the actual performance of the movement. For safety, these muscles should not be fatigued before lifting heavy weights or performing more complex movement patterns.

Compound exercises also mimic primal movements performed within functional, day-to-day activities. E.g., an item isn’t simply lifted by only the triceps, so let's train all the muscles used in an action to better increase the action's performance. On the flipside, if the triceps were an area of concern that needed to be focused on, this could be done via isolated and compound exercises.

The theory behind compound before isolated exercises is that it helps to prevent fatigue of the agonists (prime movers) before asking them to perform their work. Should these muscles be fatigued, they will then be less able to perform optimally. This places more responsibility on the smaller, more stabilising muscles (antagonists, synergists, and fixators). This is risky as their role is to support and ensure a smooth performance of the movement. They are not there to perform the movement themselves.

Imagine a client has a 100kg squat to perform as part of their routine. They can comfortably perform 8 reps and 3 sets of this exercise. They also have a 20 min run on a treadmill, lat pull downs, push ups, bent over rows, and calf raises to do within their routine. With this exercise plan in mind, it would be a scary idea if the client was expected to do the near-max performance of 100kg squats towards the end of their programme. Imagine how fatigued the muscles in their lower body would be and how risky that movement could be.

In a squat the quads, hamstrings, and glutes play the largest role in the movement. Supporting muscles include hip flexors and extensors, muscles of the core and lower back as well as hip abductors and adductors to a certain extent. Imagine a client who is fatigued in the main, large muscle groups and then embarking on performing a 100kg squat. The pressure would be on the smaller, more supportive muscles, literally! Ouch!

Benefits

Other key reasons why it is beneficial to programme compound exercises before isolation exercises include:

- They simulate real-life, functional movements.

- More time-efficient: Why work each muscle independently (unless you have to) when you can be efficient and train multiple at the same time? Less is more.

- Increases calorie burn: Muscle activation stimulates hormone release. The bigger the muscle, the larger the hormone release. This benefits both the workout itself and the calorie burn achieved as a result.

- Decreases the risk of injury when performing sports or other activities: Muscles are stronger and more capable.

- Enables work to be performed longer before muscle fatigue sets in: Large muscles fatigue slower than smaller muscles.

- Allows the build-up of strength and, therefore, the lifting of heavier weights.

Unless rehabilitation is the goal or to build up a particular muscle for competition- who wouldn’t compound before isolating?

Scenario: Large before small

Let's have a look at Bella's full-body programme again. Notice how the lower body compound movements are first, the upper body (smaller muscle groups) follow, and the programme concludes with the less taxing abdominal exercises.

Bella's programme

Warm-up: Assault bike 15 calories

Mobilisation/activation: 5 reps of the following:

- Open the gate

- Cat/cow

- Thread the needle

- Walk the dog

- Glute bridges

| Exercise | Rest | Set 1 | Set 2 | Set 3 | Load | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goblet squat | ss | 15 | 15 | 16kg | Lead with hips | |

| Walking lunge | ss | 12 | 12 | Back knee to floor | ||

| Powerbag hip thrust | 60s | 15 | 15 | 20kg | Squeeze at top | |

| Dumbbell bench press | ss | 8-10 | 8-10 | 7kg | Controlled movement | |

| Ring row | ss | 10 | 10 | Squeeze shoulder blades | ||

| Russian twist | ss | 10 | 10 | Touch toes |

Accountability habits:

- Average 9,000 steps per day

- At least 3 exercise sessions per week

- Aim to keep portion sizes to guidelines

You will see that this is a well-balanced programme with each of the primal patterns featuring at least once.

Try it out

Watch

How did you go? Watch this short clip where Ben explains the rationale for the order of the exercises.