In this section, you will learn to:

- Conduct an initial counselling session.

- Establish and confirm the nature of the helping relationship.

- Use appropriate counselling skills.

- Develop a counselling plan.

Supplementary materials relevant to this section:

- Conduct an initial counselling session.

- Reading G: Start the Counselling and Helping Process

- Reading H: Integrating Skills of the Exploration Stage.

The first two sections of this module focus on laying down the foundation work – we have explored what counselling is, the counselling relationship, and a range of practice considerations in counselling practice. In the final section, the focus is on the counselling process – we will look at how counsellors bring all of these understandings and skills together in the actual counselling process, particularly in the initial session.

Let’s begin with an overview of a generic counselling process.

While counsellors from different theoretical orientations will have different approaches to the process, most forms of counselling will follow a similar basic structure that is comprised of a preparatory, beginning, middle, and ending phase. The following table provides an overview of the counselling process and outlines primary tasks and events carried out in each of the four phases (adapted from Horton, 2012, pp. 122-127).

| Phase | Goals/tasks of the phase |

|---|---|

| Preparatory Phase |

|

| Beginning Phase |

|

| Middle Phase |

|

| Ending Phase |

|

Keeping this structure in mind as you complete this section, and the future modules, will help you learn the fundamental aspects of counselling. However, it is important to note that this counselling structure is a generic guide only. The process that each counsellor uses will vary depending on the modality they use, their organisational context, the clientele whom they work with, and whether they work with individuals or multiple clients. Additionally, the counselling process does not usually progress in a linear manner:

As a structural overview of the developmental process, the framework provides therapists with a sense of grounding and direction. But it is only a cognitive map and as such cannot reflect the actual experience or dynamics of a process that seldom, if ever, follows a straightforward linear progression through discrete and clearly defined phases. As the relationship between therapist and client develops, new issues may emerge, goals are evaluated and often redefined, and earlier phase-related tasks may be revisited and worked on more deeply. It is a fluid, multidimensional and complex process.

(Horton, 2012, p. 122)

Moreover, while a counsellor will have a particular or preferred structure in mind when they meet with a new client, counselling is a collaborative or interactional process; hence it is important to be flexible and responsive to a client’s individual needs. Counsellors should aim to clarify the client’s expectations of the process and use appropriate communication techniques to facilitate a collaborative agreement on how the client may best make use of the counselling process.

In sum, a counselling process is not set in stone and needs to be tailored to meet the client's needs. Therefore, it is important that, as a counsellor, you remain flexible, patient, and willing to adapt the counselling structure in accordance with the client’s needs. It is also important to note that you will ultimately be guided by the organisation that you work for. Many organisations have preferred methods, and you may be limited by the kinds of services they are equipped to provide. For example, while you may prefer to spend twenty sessions with a client, your organisation may be time limited and only allow six sessions. It is good practice to inform the client of all of these factors from the outset in order to clarify their expectations and understanding of the counselling process and the services offered by your organisation.

In the remainder of this module, we will focus primarily on the initial counselling session (and the subsequent sessions will be covered in the following modules), which may include the ‘preparatory phase’ but more typically resembles the start of the ‘beginning phase’.

Reflect

Imagine that you are a client who is entering a counselling session for the very first time. How would you feel if you knew very little about counselling and was unsure of what to expect? What information would you expect from the counsellor in order to feel sufficiently informed about the process?

Check your understanding of the content so far!

The initial session is important as it lays down the groundwork for the entire counselling process and significantly reduces the likelihood of misunderstandings further down the line. It is also often the first face to face contact you will have with your client and sets the tone of subsequent counselling interactions.

Each counsellor will have their own personal style when conducting an initial session; however, the main events involved in this session generally include the following:

- Promoting and clarifying the client’s understanding of the counselling process, including what they can expect from the process and what approach you may use.

- Providing information and confirming the client’s understanding of organisational services and requirements. This may include information about what type of service the organisation offers, cancellation policies, and payment schedules.

- Exploring any anxieties or concerns the client may have about engaging in counselling or organisational requirements.

- Signing a counselling contract.

- Developing an understanding of the client’s needs, concerns and circumstances.

- Assessing significant risk or safety issues or referral needs.

- Prioritising needs, identifying preliminary goals and discussing options.

- Creating a counselling plan in consultation with the client.

Preparation Before Session

For you as the counsellor, the counselling process begins before the client even arrives. Adequate preparation ensures that you are aware of important information about the client and are relaxed and mentally prepared to engage with him or her. Specific attention should also be paid to the counselling environment. It is good practice to:

- Arrive early to check the room and adjust seating, lighting and window coverings.

- Ensure the room is clean and tidy, and check for trip hazards.

- Place a box of tissues within easy reach of the client.

- Read through any referral reports or case notes from the previous counsellor.

- Prepare yourself – doing a few simple physical relaxation techniques, breathing exercises, or just sitting in silence for a few minutes can help you mentally prepare.

If there is a referral form attached, it may contain information that the counsellor needs to take into account to work appropriately with the client. For example, a referral form may indicate possible health or mental health concerns (e.g., a client has been referred by a GP for anxiety management), reporting requirements (e.g., a client has been mandated to attend counselling as part of a parole program), or risk issues (e.g., history of suicide). Note that you should not fully rely on the existing referral information as the client’s situation may have changed – instead, seek clarification from clients as they are the best source of information.

Reflect

Take a few moments to reflect upon the importance of preparation. Imagine that you are a client attending your first-ever counselling session. How different would you feel entering a tidy, well-lit, and organised room with a counsellor who appeared relaxed, compared to entering a room with a counsellor who appeared to be stressed and rushed around, moving chairs and turning on lights before you could sit down?

Read

Reading G: Start the Counselling and Helping Process

Reading G discusses some common counsellor tasks and skills involved in commencing the first counselling session (based on the life skills counselling model). Remember that these are merely generic guidelines; counsellors must adapt their approach to suit their individual styles, clients’ needs, and organisational context.

When you first meet a client, it is important that you greet your client by name and introduce yourself. As most people can feel uneasy entering a strange environment, it is useful to incorporate some brief ‘small-talk’ with clients to help them settle in and become comfortable with the session. You may say, for example, “Hi Lauren, my name is Alex. Thanks for coming. I hope you had no trouble finding us?”

Remember to use your microskills to build rapport with the client and help them feel comfortable. You may also want to stay at surface-level conversations (e.g., general details or day-to-day topics) instead of jumping straight into a discussion of issues immediately to allow more space for rapport building. Particularly if you are walking your client from a waiting room into a counselling room, it is important not to discuss any sensitive or confidential information until you have entered and settled in a private room.

Some counsellors might choose to briefly explore the client’s issues at this point, such as by asking, “What would you like to talk about today?” or “Would you like to tell me briefly about what’s brought you here today?”. Through the demonstration of microskills and empathy in this brief ‘opening’ conversation, counsellors focus on building rapport with clients and developing an initial understanding of the client’s expectations of counselling. Nevertheless, the focus should be on relationship building at this stage and gently preparing the client for contracting conversations instead of gathering information.

Addressing Anxieties about Counselling

New clients are often anxious, upset, or in turmoil. If they are new to counselling, they may not know what to expect from the session. Some clients may have difficulty with the idea of opening up to a complete stranger and sharing stories and concerns that they may not have shared with their closest friends and family. You may identify this through their body language, such as hand wringing, foot tapping, abrupt or brusque answers, avoiding eye contact, or the client’s verbal statements. Of course, it will not be appropriate to make assumptions and make comments such as, “Are you anxious?” or “Are you are having a panic attack?”. Rather, take a tentative and respectful approach. Strategies that counsellors may use include:

- Ask an open question: e.g., “How do you feel about coming to counselling, Andy?”

- Normalise their anxiety: e.g., “Most people find it quite nerve-wracking to come to counselling. I’m not sure if you are feeling the same way?”

- Reflect on what you have observed: e.g., “Henry, I noticed that you seem a bit uneasy, is everything alright there?”

As the client responds, make sure that you acknowledge and respect their concerns instead of simply dismissing them. It can also be useful to explain what is likely to happen in the session so that clients feel more in the ‘know’ – also known as ‘structuring’ the session.

For example, you may say:

“We’ve set aside about 40 minutes for this appointment today. We'll take some time at the start of the session to go through important information about the counselling services, so you have a good understanding of what is involved and what support we can offer you.

Then we can discuss your concerns and talk about some options to address these concerns. About ten minutes before the end of the session, I usually wrap up the session, and we can talk about how you might want to proceed from here.

How does that sound to you?”

As always, it is important to check and confirm the client’s understanding to ensure you are both on ‘the same page’.

An important objective of the initial session is to establish a shared understanding of what the counselling process will entail. It is important that when clients engage in counselling, they understand exactly what is involved, including the risks and benefits of counselling. As you have learned in Section 2, this is often established through the contracting process, in which clients are made fully aware of what to expect before they provide informed consent to engage in the counselling process. To obtain informed consent, the counsellor must ensure they have provided sufficient information to help the client decide whether to participate in the counselling service on offer.

Information that you will discuss with clients generally includes:

- Information about the counselling service, for example, what resources and services the organisation can offer; how many sessions it usually takes, and how long each session is; payment schedules, cancellation policies and terminatiseeon procedures.

- The counselling approach you intend to use. A client may have worked with other counsellors or seen an example of counselling and assume all counsellors work in the same way. For example, a client may like the idea of a particular kind of counselling, such as cognitive behavioural therapy, and want to work in this way. However, if a counsellor and their agency/organisation only work from a specific approach, then the counsellor would need to explain this method to the client so that they have an understanding of what is involved and can decide whether they would be happy with this service. You might prepare a short introduction, such as the following example, then after, a check-in question:

We’ll talk about what’s been going on for you, and I’ll encourage you to come up with ideas and options to change things. I won’t be giving you lots of advice or telling you what to do.

If you have something going on that needs more specialised care, we also have great links with other agencies, so I can also refer you to other services if it’s a better way to go.

Does this sound like what you had in mind?”

If the client prefers another counselling approach or you feel that the current service is not appropriate for the client’s particular preference or needs, you should offer to refer the client to a more appropriate counsellor/service.

- Privacy and confidentiality information. It is important to help clients understand how information is handled and make them aware of circumstances in which confidentiality may be overridden, including:

- If the client discloses that they may harm themselves or harm may come to them;

- If the client discloses that they may harm others or;

- If the client’s file is subpoenaed by a court of law; or

- If the client has provided written permission for you to do so.

- Boundaries and limitations of the counselling relationship. It is useful to clarify what your role and responsibilities are as counsellors and what you can or cannot do to establish a mutual understanding of the relationship. This may be when clients initially contact you and in situations when clients will need to seek emergency support.

Typically, your organisation would have developed policies around contracting as well as formal contracts that you may use to assist with this process. A counselling contract is essentially a document that summarises what the client can expect from the counselling process as described. It also helps the client develop realistic expectations of the counselling process and relationship and allows them to understand the level of commitment that is expected of them (e.g., attendance at appointments, payment.). While each organisation will have their own format, here is an example of a counselling contract for you to review.

|

Wellness Counselling Centre Counselling Contract |

|

Counselling approach

I believe that my clients have the desire and the capacity to grow towards fulfilling their true potential and that they are the experts on their own lives. Therefore, I will not give you advice or offer solutions but will work with you to help you understand yourself more fully and to find your own inner resources. With greater self-awareness and trust in yourself, I hope that you will be able to make constructive changes, leading to a more satisfying and meaningful life. Confidentiality The content of the sessions will be treated as highly confidential. I will need to discuss my work with my supervisor, and I will only use your first name but not any other identifying details of you. However, there are a few circumstances in which I may be required to break confidentiality:

Sessions Our initial contract will run for 6 sessions, after which we will review the counselling process and negotiate further sessions as appropriate. Normally we will meet on a weekly basis at a regular time. The duration of the counselling session is 1 hour. Payments/cancellations Each 1-hour session costs $120. Payment will be taken at the beginning of each session and may be made by cash, EFTPOS, credit card, or cheque. Late cancellation fees are payable as follows: 0-24 hours’ notice – full session fee payable. 24-48 hours’ notice – 50% of the session fee is payable. Record keeping I will take notes during or after each session to help me keep track of our progress together. These notes will be stored in a private and secure location and may be viewed by you if you so wish. Your counselling records will be kept by the service for a period of seven (7) years from the date of your last contact with the service. Email/telephone contact Email or telephone contact will be limited to practical arrangements only. I will not enter into telephone or email counselling except by prior arrangement. If you are faced with an emergency in between sessions, please contact the appropriate emergency service (see overleaf). In a life-threatening situation, call 000 without delay. Ending counselling Normally, the end of counselling would be by prior mutual agreement. However, you have the right to end your counselling at any time. I would appreciate you letting me know if you decide not to return to counselling, giving at least 48 hours’ notice. If at any time I feel that our counselling is no longer appropriate for you, I will discuss this with you and may suggest discontinuation or a referral to a more appropriate service. Client Signature: Date: Counsellor signature: Date: |

Reflect

Why do you think it is important for a counsellor to go through the counsellor contract with a client? What do you think could happen if they do not take the time to do this?

Remember that some clients who are experiencing emotional distress may struggle to take in all information at once, while other clients may have literacy issues that impede them from reading or understanding the contract. Thus, you should not just provide your clients with the contract; it is important to take the time to explain the details in the contract and invite questions from clients to obtain informed consent. By signing the contract, clients are giving their explicit consent or agreement to the counselling treatment as outlined in the contract. They are also agreeing to the payment and cancellation notice requirements and confirming that they understand confidentiality and privacy/record-keeping arrangements.

Initiating the contracting conversation can be challenging at times. Understandably, some clients would want to offload information about their issues and circumstances as soon as they get into the session. In this case, it is important that you do not dismiss their concerns but utilise appropriate listening skills to acknowledge their concerns and gently guide them in the conversation.

For example, you may say:

“Henry, I can hear that this is important for you, and I’d like to hear more about it in a moment. But before we get there, there is some important information that I need to discuss with you to make sure that you have a good understanding of what is involved. Is that alright with you?”

It is also helpful to introduce the conversation in a normalised way, such as by saying:

“Usually, at the beginning of the first session, I’ll go through some basic information about the process to make sure that you have a good understanding of what is involved and decide if this is the right process for you. If at any point you need clarification or have any questions, please feel free to let me know. How does this sound to you?”

Once you have gone through these essential elements with your client and answered any questions they may have, you should request the client to sign the contract and provide them with a copy of the signed contract.

A significant part of the initial session will be spent on gaining a broad understanding of the client’s concerns and circumstances. Arriving at this point of the session, you may already have some understanding of the immediate needs or concerns that a client has; however, additional information may be required to generate a fuller picture of the client’s circumstances.

For example, it may be useful to ask questions around:

- What are the most pressing issues/concerns?

- How long have the issues been in place? When did they first start?

- What impacts are the issues having on the client’s life?

- How has the client attempted to manage the concerns?

- Who are involved? Who has the client turned to for support?

Once again, it is important to acknowledge and show respect for the client’s concerns using the counselling techniques and microskills you learned about in the previous section of this module. For example, you may use receptive body language, encouragers, paraphrasing and reflecting feelings, and appropriate questions to expand understanding of the client’s concerns. Using appropriate techniques at an appropriate time will also help facilitate rapport and enable the client to feel validated.

Remember that this should not come across as an interrogation – as previously mentioned, questioning needs to be used sparingly alongside other counselling techniques – you should aim to facilitate the client’s exploration and, at times, summarise or reflect back what you have heard instead of focusing entirely on information gathering.

If you notice that the client is in distress or finding it difficult to express their concerns, it may be appropriate to focus initially on the more factual elements of the client’s situation or focus on helping the client regulate their emotions. Ultimately, you want to be led by the client and ensure you look after their emotional safety.

Assess for Risk and Referral

Occasionally it becomes evident during the initial session that the issue the client is presenting with requires the input of specially trained professionals. You have learned about the work-role and limitations of a counsellor in the previous section (it may be helpful to review “Work-Role Boundaries” and “Referral” in Section 2 before continuing). In these cases, counselling may not be the most appropriate way of meeting the client’s needs and you should consider referring the client to a more suitable professional. For example, a client seeking help concerning trauma-related issues may be best referred to a trauma specialist. Suppose you believe a referral may be required. In that case, you should always discuss the referral options with your client, explaining why you believe they will benefit from the referral and providing clear information about the process.

As part of your duty of care, you will also need to look out for potential risks or safety issues that may be affecting the client. Occasionally, a client will present with threats of suicide, self-harm, or harm to others that may necessitate the involvement of emergency services and/or specialist interventions. Risk and safety must be documented in the counselling plan as well as any other relevant organisational documents as per the policies and procedures.

Read

Reading H: Integrating Skills of the Exploration Stage

As you have learned in Section 1 of this module, counsellors apply various counselling skills and techniques to build rapport with clients while developing an understanding of the client’s concerns. Reading H provides an overview of skills that helpers use to facilitate the exploration of client concerns. The author also discusses some common difficulties that beginning helpers may encounter in implementing these skills and some strategies you may use to address these difficulties.

This reading also includes an example transcript demonstrating the integration of various counselling skills in an initial helping session.

Check your understanding of the content so far!

Once you understand the client’s concerns and issues, you can work with the client to identify how counselling can be best used to assist them. Remember that this needs to be done collaboratively – while counsellors may be more knowledgeable about the process, promoting the client's sense of ownership in the process is vital for encouraging a commitment to counselling. It is also unethical for counsellors to impose their preferences or agenda on the client; instead, counsellors support their clients by developing achievable goals and a plan for meeting those goals.

Identifying Priorities and Goals

Often, multiple issues emerge from the client’s story, in which case you will need to work collaboratively with clients to decide on which issue they would like to address first while documenting all the other issues for subsequent attention. Be careful not to fall into the trap of talking the client into focusing on the issue you feel is most important or over-reliance on issues identified in any referral information.

This involves encouraging clients to understand their current situation and consider exactly how they would like to improve it. You should encourage clients to think about their overall goals and how these would fit in with their current circumstances. Some questions that might be asked include:

- What changes are necessary to alleviate the distress caused by this issue?

- What will we need to change to bring about the desired result?

- How will we know if the change has occurred?

Although goals are continuously reviewed and may be modified later in the counselling process, establishing an initial set of goals in the first session increases the continuity of sessions, gives some structure to the counselling process, and enables the client and counsellor to assess progress. Here are some important tips for goal setting:

- Identify broad goals. These often affect important areas of functioning – for example, family, work, social relationships, financial concerns and health. Broad goals are derived from the client’s presenting problem.

- Prioritise. This process involves determining the most central issues that cause concern and arranging them from most important to least important. Starting with the problem that has the best chance of being solved can help increase the patient’s commitment to counselling.

- Break each goal into smaller steps. This will help the client accomplish the goal without feeling overwhelmed by a huge task.

Exploring Options

Once the client has decided upon realistic goals, it is important to help him or her consider how each goal might be achieved through counselling. One commonly used technique at this stage is brainstorming with the client all potential courses of action to achieve identified goals. You can then support clients in considering costs and benefits, what specific steps would need to be taken, and the possible consequences of each course of action. Sometimes a client may be unsure how to achieve the specified goals, and the counsellor may suggest potential strategies based on their experience; however, it is important to present these opinions as tentative suggestions only and not something to impose upon the client.

For example, Melissa’s goal is to develop the confidence to express her thoughts to her parents. Possible options may include learning and practising assertive communication skills, writing her thoughts in a letter to her parents, obtaining support from another trusted family member who can facilitate the discussion, and practising relaxation strategies she could use before talking to her parents. Melissa may decide that she would like to focus on learning relaxation strategies in the next counselling session.

Ultimately, the counsellor and the client will work collaboratively to decide how counselling can be most appropriately used in the client’s best interests. It is important to help clients consider the practicalities of options and their willingness to commit to specific actions required to achieve their goals. As always, clarify and check the client’s understanding to ensure you are both on the same page. Finally, you can record the discussion details using a counselling plan.

A counselling plan is a way of documenting the information that the counsellor gathers throughout the first session with a client. It is essentially a record of client information gathered through talking with the client as well as the agreed priorities or goals of counselling. Developing a written counselling plan can bring several benefits, for example:

- It helps to ensure both the counsellor and the client are on the same page regarding the outcomes of their discussion. In the process of developing a written plan, counsellors can clarify and confirm a client's understanding of how the counselling process will be undertaken.

- Having a written plan helps clients to visualise goals and may increase the clients commitment to achieving goals and to the process.

- The plan helps to keep the counselling process on track and allows evaluation of progress (e.g., whether the goal has been met or progress has been made).

- It helps to provide continuity in the counselling process. For example, suppose you cannot continue counselling a client for some reason. In that case, another counsellor should be able to use the counselling plan to continue the counselling process rather than having to start all over again.

A counselling plan is typically completed during or immediately after the first session by documenting the information gathered in that session. As well as documenting information and the outcome of the initial session, the counselling plan also sets out ‘check points’ in the counselling process – certain points when the counsellor will request feedback from the client to ensure they are satisfied with the counselling process and is progressing. Importantly, a counselling plan is never set in stone; it should be reviewed and updated to reflect changes in clients’ circumstances or priorities.

Apart from the client’s identification information (e.g., name, date of birth, contact details), elements documented in a counselling plan typically include:

Any safety or risk issues

For example, if the referral report indicates that the client has a history of aggression, you should document this in the counselling plan and ensure appropriate strategies are in place (e.g., duress alarm; make sure there are other staff around). Sometimes you may become aware of other risks, such as suicidal thoughts, DFV issues and child safety concerns which you must document and address according to your organisational policies and procedures.

Special needs information

This may include any information about the client that is important to consider during service provision. For instance, it is important to note mobility issues, hearing difficulties, or the need for an interpreter that may require adjustment to the counselling process. A client with safety concerns may request to have all communications of counselling appointments made through her private email. You may also note down any factors that may affect a client’s capacity to attend and commit to counselling, such as the client working shift work and hence requiring confirmation of appointment one week ahead; the client may require a reduction in fee due to financial difficulty.

Other agencies or helping professionals involved

It can be useful to list an agency that has referred the client to counselling (if any) or other professionals or support services with which the client is engaged. These details can help understand a client’s access to support systems and resources and if the client wishes to share the content of their discussion with another service.

The self-identified needs, concerns and goals of the client

This may include what the client has identified as priorities and their intended counselling outcomes.

Goals of counselling

This refers to the agreed priorities and goals the counsellor and client collaboratively determined, which may differ from the client’s self-identified goals. However, both should be recorded in the plan.

Counsellor’s observation of clients

During the session, the counsellor may have observed or noted client statements or behaviours requiring further exploration in the following sessions. For instance, a counsellor may note that a client was very upset when asked about their relationship with a specific family member so that the counsellor can follow up or take this into account in future sessions. Remember that any observation about clients must be written in a clear, factual way. You should record the exact words that the client has stated (e.g., the client stated that…) and your perspective as an ‘observation’ (e.g., Client seemed upset…) instead of a ‘conclusion’.

Evaluation strategies

Evaluation strategies ensure that the client is satisfied with the counselling you provide and is progressing towards achieving his or her goals. While numerous methods are available to monitor counselling progress, some of the most commonly used methods involve giving the client a feedback form to fill in or conducting a verbal review of the counselling process with the client. The frequency of reviews is up to you and your client. Some counsellors choose to conduct a brief review after every session; others choose a predictable timeframe, such as every three sessions or every six weeks. Some organisations will have procedures outlining how counselling reviews are to be conducted. You will learn more about feedback processes later in this course. For now, the main point to remember is that you should have some agreed way of evaluating whether the counselling you are providing is helping your client.

Check your understanding of the content so far!

Now that you have learned about the various tasks involved in an initial counselling session, let’s have a look at how this might work in an actual client session. You will read about a counselling transcript between a client, Julie, and her counsellor, Tom. We encourage you to take note of how Tom uses various counselling techniques to facilitate the session as well as develop rapport with Julie. A copy of Julie’s counselling plan is also included at the end of this section.

Address anxieties about counselling process

| Julie's First Counselling Session | |

|---|---|

| Julie is Tom’s first client of the day. Tom has arrived a little earlier than the scheduled 9 am start to check the counselling room, which had been used by another counsellor the previous day. There is a referral report from Julie’s doctor in Julie’s new client file, and Tom has a quick look through this to get a general idea of the issues that Julie might be dealing with and to note any safety or risks that he should be aware of. The report does not mention any specific concerns. Tom takes a few minutes to clear his head by closing his eyes and breathing deeply. He then goes into the reception room to meet Julie and shows her to the counselling room. | Preparation before session |

|

Tom: “Hi Julie, I’m Tom. Please come in, sit down. Was it easy to find your way here?” Julie has never sought counselling before and feels very anxious and nervous. She is sure the counsellor will ‘tell her off' for letting her temper get the best of her and is worried about how she will react in the session. Tom notices that Julie seems anxious – she is fidgeting and her face is a bit flushed. He starts by asking her if she would like to know a bit more about the services available at the practice and what counselling might involve. Julie is relieved as she has no idea of what to expect. |

Greeting and rapport building |

| Address anxieties about the counselling process | |

|

Tom: “We offer a counselling service here, which means I’ll be aiming to help you figure out what’s been affecting your life and put together a plan to improve things. I work from a person-centred approach which means that I believe that you’re the expert in your own life and ultimately have the ability to make the changes you need to. We’ll talk about what’s been going on for you and I’ll be encouraging you to come up with ideas and options to change things. I won’t be giving you lots of advice or telling you what to do. We’ll start with six sessions, but we can extend this if we both agree it’s needed. If you have something going on that needs more specialised care, we have great links with other agencies, so I can refer you to other services if it’s a better way to go. Julie feels much less vulnerable and more in control after hearing this. She had assumed that the counsellor would tell her what was wrong with her and give her a long list of instructions on what to do. Julie tells Tom she likes the idea of being an ‘expert’ and having some say about how things go. Julie feels very concerned, though, about people finding out about the road rage incident and thinks that Tom might even contact child protection services because of her temper. She asks him if he will tell anyone about their sessions. |

Provide information about the services |

| Explain your counselling approach, the process and expectations | |

| Explain referral processes | |

| Clarify and confirm client understanding of the counselling process | |

| Tom: “Everything you tell me stays in this room except if I believe you might hurt yourself or someone else. Then I’ll need help from other people to keep everyone safe. Also, if the courts subpoena your case notes for any reason, I’ll have to let them see those. You might even give me written permission to get someone else involved. In any event, I’ll let you know what I’m going to be doing first.” | Explain confidentiality limitations. |

| Tom then went on to explain a bit about how the practice worked, including payment schedules and cancellation policies. Julie didn’t know that she would need to cancel her appointment with 48 hours' notice, so was grateful to be told that. Tom also reassured Julie that her case notes would be kept in a locked drawer at the practice. Tom gave her a copy of the counselling contract, which contained all the information they had discussed and asked her if she had any questions. Julie was happy that Tom had explained everything and signed the contract. She was given a copy to take home, which was useful as she didn’t remember everything they had discussed. |

Explain organisational policies Contracting |

|

Although now feeling much less anxious, Julie has no idea where to start her story. Tom can see that Julie is feeling unsure. He leans in slightly to let her know he is listening to her and makes eye contact. Tom: “Perhaps you could tell me a little about what’s brought you here today.” Julie: “It’s my temper. I have problems with my temper.” Julie: “Well, there was this road rage incident...” Julie trails off. Tom can see she is embarrassed. He smiles reassuringly and nods, being careful to indicate a non-judgmental stance. Tom: “Uh-huh” |

Body language |

| Open question | |

| Paraphrasing and open question | |

| Encouragers | |

| Reflection of feeling Open question | |

|

Julie goes on to describe what happened at the school and tells him a little about how it felt. Tom: “So, really, you were already feeling quite stressed out before it even happened. The kids were late for school and arguing in the back and it was important to you that they were on time. You felt it building up like a volcano inside and then when the other mother pulled out in front of you, it felt like an elastic band snapping. Have I got it right? Julie: “Yes, that’s exactly how it felt! I just seem to feel so angry all the time and then it just takes something small to tip things over.” |

Summarising |

|

Tom identifies Julie’s immediate need/concern and checks in with Julie to make sure they’re on the same page. Tom: “It sounds like this issue with anger is having a really big impact on your life, and I’m guessing you’d like to deal things with things differently in the future? Is this what you’d like to focus on in your counselling sessions?” |

Clarifying client’s priorities and concerns |

| Tom has listened carefully to Julie’s story and he has not identified any safety or risks that need to be addressed. Her issue is within his field of competence and experience and he does not believe she needs specialised treatment. | Assess risks and safety Consider referral (if necessary) |

| Tom works with Julie to explore initial options to improve her situation. Julie tells Tom that the anger seems to come out of nowhere and Tom suggests that maybe it would be a good idea to start by figuring out what tends to ‘trigger’ Julie’s anger. As the unpredictability of the anger is really scary for Julie, she thinks that is a good idea. They agree to focus on this in their next session and Julie promises to notice instances over the next week when she feels angry. Julie also says she would like to learn relaxation skills and ways of calming down and also discuss new rules for the children with her husband. |

Agree on priorities Develop goals Explore options |

| In the last 5 minutes of the session, Tom explains that he’d like to get some feedback from Julie in their third session to check that things are on track and make sure Julie is happy with the approach Tom is taking in their counselling sessions. Julie is surprised but relieved that she can tell Tom if something is not working for her in the counselling sessions and not just have to put up with it. They set an appointment for the following week and Julie leaves. | Discuss and agree monitoring process |

| Tom has 10 minutes until his next client appointment, which he uses to complete Julie’s counselling plan ready for the next session. He notes the name of Julie’s doctor as a contact. There are no special needs that he has identified. He then documents the priorities and goals that Julie has identified, as well as his own ideas about what might be needed. Details of the monitoring process they have agreed to (i.e., feedback after session 3) are also documented. | Develop the counselling plan |

| Tom then takes a few minutes to clear his head, checks the room for tidiness and goes to the reception room to find his next client. | Preparation for next session |

Reflect

Reflect upon Tom’s actions as a counsellor in this example. Can you see how he used counselling microskills to help Julie open up and share her story? Can you see how Tom has structured the initial counselling session to help ensure that Julie was fully aware of the counselling process?

In a nutshell, counsellors follow a structured approach in the initial session of counselling to set the scene for effective counselling. It is important for counsellors to:

- Explain the counselling process.

- Clarify client expectations of the counselling process through contracting.

- Identify immediate client needs.

- Agree on goals to work towards.

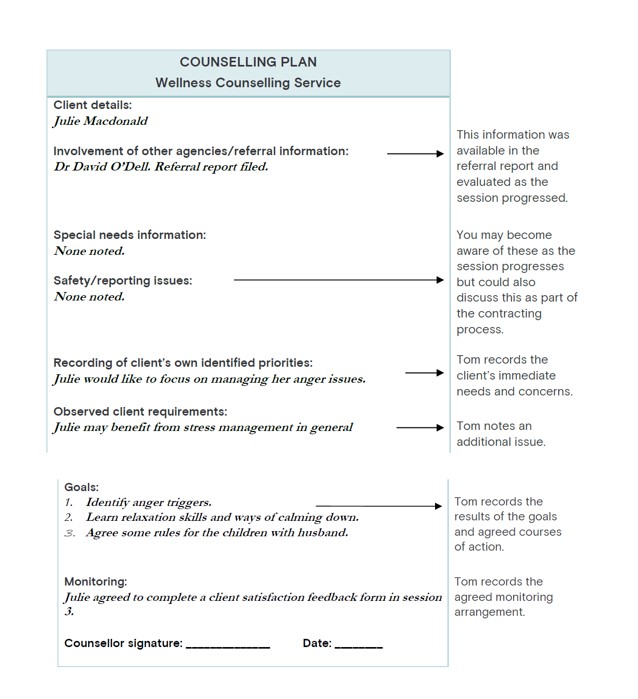

Counsellors also use counselling skills and techniques to help clients tell their stories and develop effective counsellor-client relationships. The information and outcomes of the sessions are recorded in counselling plans. Review the following example of a counselling plan Tom might develop for Julie.

In this example, you can see the main sections of the counselling plan and how Tom gathers the information required to complete each section. While different organisations will have different formats for counselling plans, this example provides a common format you can use in your first session.

Congratulations on completing this module! This module introduces you to the profession of a counsellor as well as the responsibilities, skills, and processes that a counsellor (or other helping professionals) may employ to establish a solid helping relationship. Remember that the helping relationship is at the heart of your work with clients. Therefore, conducting the initial session effectively is a vital first step. In the following modules, we will continue to build on and expand the counselling knowledge and skills you have learned in this module.

- Horton, I. (2012). Structuring work with clients. In C. Feltham & I. Horton (Eds.), The Sage handbook of counselling and psychotherapy (3rd ed.; pp. 122-128). London, UK: Sage.

- Nelson-Jones, R. (2014). Practical counselling and helping skills (6th ed.). London, UK: Sage.