Communication can be defined as the process of exchanging information, thoughts, or feelings between people.

Effective communication is key to building positive, supportive relationships with tangata and their whānau.

Communication occurs in physical space, cultural and social values and psychological conditions. Communication happens with and without words.

So how do people decode the message we're trying to communicate?

- the words you're trying to convey only accounts for less than 10%

- the tone of voice or how you say what you say accounts for nearly 40%

- and body language plays the most important role. This accounts for over half of the overall experience, 55% or more

As a support worker, you will need to communicate with tangata, other professionals, their whānau, and the community.

Types of communication

Using a careful combination of all the communication types will help you succeed in your role in healthcare.

Here are the four main types of communication:

- verbal communication (spoken)

- non-verbal communication (body language)

- written communication

- visual communication

Verbal communication

Verbal communication is the most common form of communication and is often placed as the primary style of communication.

- Spoken Language. Using words and vocal sounds to communicate ideas, thoughts, and feelings through conversation, presentations, speeches, or discussions.

- Tone of Voice. The way words are spoken, including the pitch, volume, and intonation, can convey emotions, attitudes, or emphasis on certain words or phrases.

- Vocabulary and Language Choice. Selecting appropriate words, phrases, and language style based on the context, audience, and purpose of communication.

- Clarity and Articulation. Speaking clearly and enunciating words properly to ensure the message is easily understood by the listener.

- Vocal Cues. Pauses, sighs, laughter, or vocal expressions like "uh-huh" or "mmm" that provide additional meaning or indicate agreement, understanding, or hesitation.

- Grammar and Syntax. Following the rules and structure of a particular language to ensure clarity, coherence, and proper understanding of written or spoken messages.

- Verbal Feedback. Providing verbal responses, comments, or questions to acknowledge, clarify, or respond to messages from others.

Languages spoken in New Zealand

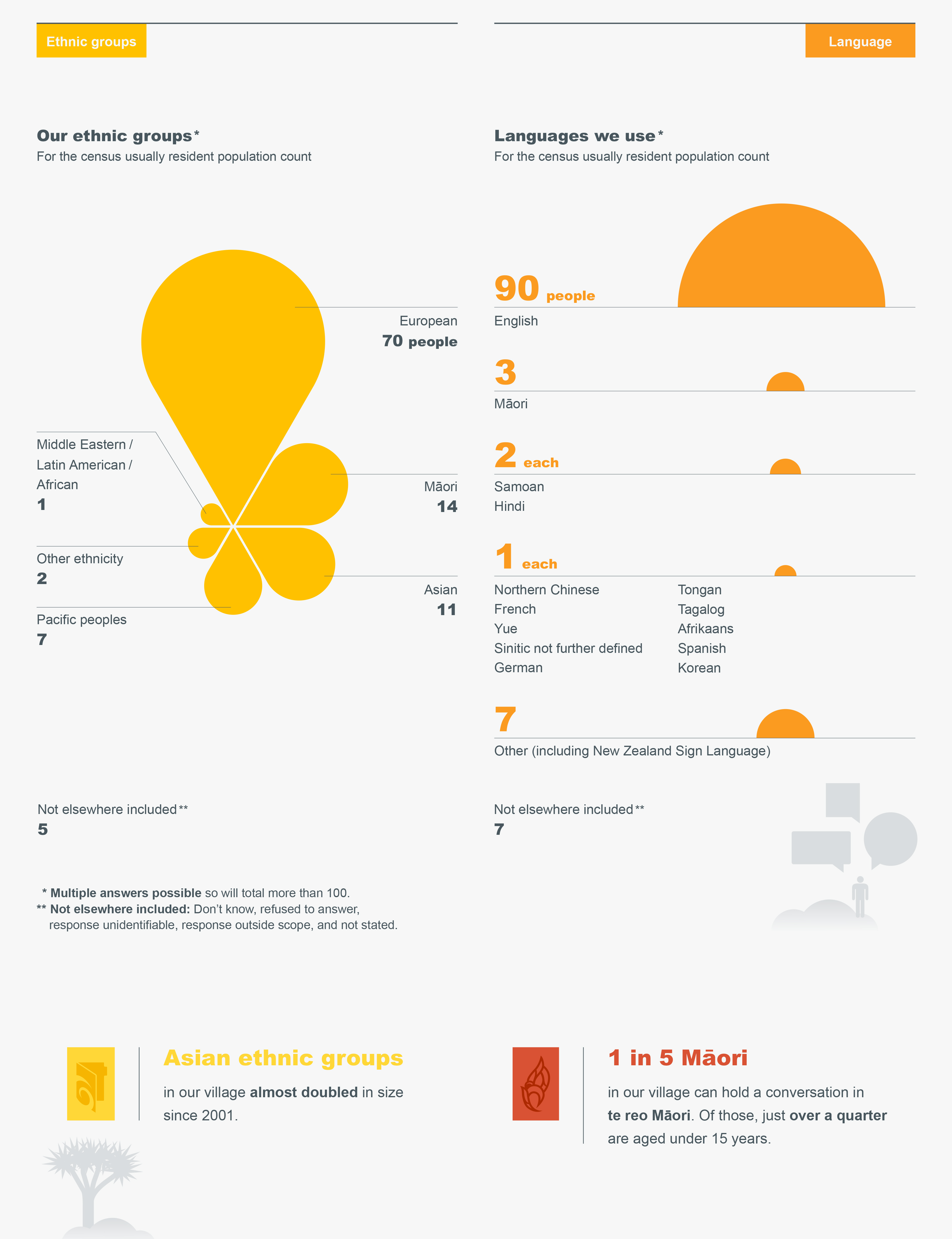

The following infographic from StatsNZ looks at New Zealand as a simplified village of 100 people.

Out of 100 people,

- 70 people are European

- 14 people are Māori

- 11 people are Asian

- 7 people are Pasifika

- and 1 person is Middle Eastern/Latin American/African

While English is the predominant language spoken in New Zealand, Māori and New Zealand Sign Language are afforded special protection and recognition as the two official languages in Aotearoa New Zealand. These were established by the Māori Language Act 1987 and the New Zealand Sign Language Act 2006.

The Māori language is considered a national taonga (treasure) and is undergoing a revival. Initiatives such as:

- te Wiki o te Reo Māori (Māori Language Week)

- kura kaupapa Māori (state schools where the teaching is in Te Reo Māori)

- broadcasting in te reo Māori on Whakaata Māori, Māori Television and Te Reo channel

all play a role in making sure Te Reo remains a living language embraced throughout New Zealand.

Te Aka (Māori Dictionary) is a great resource and includes recordings of words so you can check pronunciation.

New Zealand is a multi-cultural country with the latest net migration gain of more than 65,000 people in the March 2023 year.

The following infographic shows New Zealand as a village of 100 people with:

- 70 people born in New Zealand and

- 30 people born overseas and migrated from all over the world

The country and region of origin of the migrants are reflected in the diversity of languages spoken in Aotearoa New Zealand. Most of the migrants are bilingual or multi-lingual and are fluent in English.

It is important to do your due diligence and find out what the service user's preferable language is. Engage an interpreter if English is not the service user’s first language or if service users have speech or hearing impairments.

There are also other impairments that might not be visible and recognisable straight away. More information is available on Cap-able's website.

Top 25 Languages in New Zealand

| Language

|

Number of speakers | Percentage of Total Population, % |

|---|---|---|

| English | 3,819,969 | 90% |

| Māori | 148,395 | 3.2% |

| Samoan | 86,403 | 2% |

| Hindi | 66,309 | 1% |

| Northern Chinese | 52,263 | 1% |

| French | 49,125 | 1% |

| Yue | 44,625 | 1% |

| Sinitic | 42,753 | 1% |

| German | 36,642 | 1% |

| Tongan | 31,839 | 1% |

| Tagalog | 29,016 | 1% |

| Afrikaans | 27,387 | 1% |

| Spanish | 26,979 | 1% |

| Korean | 26,373 | 1% |

| Dutch | 24,006 | 1% |

| New Zealand Sign Language | 20,235 | <1% |

| Japanese | 20,148 | <1% |

| Punjabi | 19,752 | <1% |

| Gujarati | 17,502 | <1% |

| Arabic | 10,746 | <1% |

When communicating with service users whose English is not their first language:

- Be aware of your own biases. Understand that you might have preconceived ideas that can affect how you talk to others, so try to recognise and challenge those ideas to have fair and equal conversations.

- Listen carefully. Pay attention to what the person is saying, let them speak without interrupting, and try to understand their point of view to show respect and understanding.

- Use clear and simple words. Talk in a way that is easy to understand, avoiding complicated terms, speaking slowly and clearly, and being careful not to sound like you're talking down to someone.

- Be patient and flexible. Remember that language barriers can take more time to communicate, so be patient, give people extra time to express themselves.

- Avoid assuming things about others. Treat each person as an individual and don't make assumptions based on their language or culture; instead, be open-minded and treat everyone fairly.

- Respect cultural differences. Understand that people from different cultures may communicate differently, so be sensitive and adapt to their communication style to create a friendly and inclusive environment.

- Ask for clarification and give feedback.

- Don't be overly focused on small language mistakes. It's not helpful to constantly correct small errors in grammar, pronunciations, etc.; instead, focus on understanding what the person is trying to say and having a good conversation.

Nonverbal communication (body language)

Nonverbal communication is the use of gestures, body language and facial expressions.

A big portion of human communication is non-verbal (55% or more). Non-verbal communication is helpful when trying to understand others’ thoughts and feelings.

This type of communication can be closed or open.

A closed body language: A service user might be showing crossed arms and hunched shoulders, it may indicate they are feeling anxious, angry or nervous.

An open body language: A service user might be showing relaxed shoulders and arms; they are more likely to be feeling positive and open to information.

When supporting tangata, be sure to display open body language to support your verbal communication. This encourages open communication.

Communication cues

It is important to cultivate the awareness for communication cues, which are actions or behaviours that indicate the communicator’s thoughts and feelings. Some of the cues or indicators can be grouped into the following:

- Kinesics. Refers to body language, including posture, body movements, and gestures.

- Paralanguage. Involves vocal cues like tone, pitch, and volume.

- Proxemics. Deals with the physical distance between individuals during communication.

- Clothing and appearance. Encompasses personal style, hairstyle, grooming, and jewellery choices.

- Chronemics. Focuses on punctuality and waiting time.

- Artifacts. Refers to objects and possessions that represent a person, such as jewelry and tattoos.

- Haptics. Involves physical contact between two individuals.

Take the time to read through the following infographics on body language designed by McKenna Fosdick.

Written and visual communication

Written and visual communication uses other things beyond our voice and body to relay a message.

Written communication includes letters, pamphlets, emails and writing which should be clear and to the point.

Visual communication is using graphics like signs, maps or drawings to convey a message.

Resources

You will come across various resources (written and visual) to assist you in your role. Research the organisations you think might be able to assist you and the service user, and explore the resources they have developed. These resources often come in different formats suitable for print or digital distribution.

You can collect these resources to educate yourself as you go through different experiences in your interactions with many service users.

Regardless of the preferred method of communication, it is important to encourage service users to take ownership of their health and wellbeing.

Health Promotion Agency New Zealand, Healthy Eating.

How to make Smoothie Pops, Allright.

What is an MDT or Multi-Disciplinary Team in healthcare?

A multi-disciplinary team is a range of health professionals working together to support the outcomes of a service user.

The MDT can include:

Multi-disciplinary care is a co-ordinated team approach to planning treatment and providing care for a service user.

Working in a multidisciplinary team

In your role, you will often be part of a multidisciplinary team. A multidisciplinary team comprises three or more people with different roles, professions or areas of expertise who work collaboratively to achieve the same goals.

Because team members have different focus areas, they may each see, think about or approach something differently. However, you all share common goals and want to deliver high-quality care.

These differences mean that the various members of multidisciplinary teams can often contribute views and perspectives about a person or situation that others may not have seen or thought about. This approach can be very valuable.

Team roles and responsibilities

Understanding the different roles and responsibilities that may make up a multidisciplinary team in a health or wellbeing setting is important. However, remember that roles and responsibilities will vary.

How a team is structured, and the exact tasks to be carried out depend on your work environment and your organisation's policies and procedures. Your organisation's policies and procedures are the principles, rules and guidelines that set out what needs to be done and how to do it. They also include anything that the law requires you to do.

Multidisciplinary team roles and responsibilities

The chart above shows a top-down management structure and where healthcare support workers sit within the team.

It is important to remember that, regardless of your role and position in the chart, your skills and contribution to the team are just as valuable as everyone else's. Your education level or pay grade does not determine your status within the team. Take pride in completing your tasks and responsibilities to the best of your abilities.

We will look at the following roles in detail:

- Tangata or Service user or Client or Patient

- Support worker

- Senior support worker

- Registered nurse

- Health professional

- Other team members

- Peer mentor

- Whānau or family

Tangata or service user or client or patient

The person who is accessing healthcare services also has some responsibilities, including:

- communicating openly and giving correct information

- actively taking part in decisions about their healthcare

- advising support workers of any changes in their health/condition

- following the agreed treatment plan

Support worker

The support worker is often the first point of contact when a person in a hospital, clinic, residential care facility or their own home needs assistance, support and care.

Typical responsibilities include:

- helping with tasks such as showering, dressing, meals and cleaning.

- assisting with rehabilitation – for example, with social skills, walking, etc.

- cleaning and preparing medical equipment and instruments, collecting and delivering files, X-rays, specimens, linen, rubbish, equipment, etc.

- working under the supervision of a registered nurse or other appropriate supervisor.

Senior support worker

As well as the support worker responsibilities, a senior support worker might typically:

- lead a shift, mentor others and deal with any conflicts that may arise.

- manage complex situations and know when to escalate or call for further support.

- communicate with families to a high degree.

- help deliver medications and identify changes in health status; be able to communicate this at a higher level.

- transfer a person between wards or departments and assist with discharges (release from hospital).

Registered nurse

A registered nurse assesses, treats, cares for and supports people in hospitals, clinics, residential care facilities and in the community. Typical responsibilities include:

- assessing, planning, coordinating and carrying out care to meet health needs.

- administering medication and intravenous drugs.

- monitoring and assessing conditions and recording important changes.

- educating service users and other staff about health needs and preventing accidents and illness.

- referring people to and consulting with other health professionals.

Health professional

A health professional is someone who is registered with an authority (appointed by or under the Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act 2003) as a practitioner of a particular health profession to deliver health services in accordance with a defined scope of practice. They will also be monitored by that authority and responsible for it. Some examples of authorities are: Medical Council of New Zealand, Physiotherapy Board of New Zealand, Dietitians Board, etc. Examples of health professionals include doctors, surgeons, physioteraphist, dietitians, etc.

Other team members

Other team members may not be registered with an authority, although they may hold a variety of qualifications and/or have different levels of experience. Examples of these other team members include paramedics, physicians assistants, etc.

Peer mentor

A peer mentor is a practising health worker who has been assigned to do peer mentoring. A peer mentor provides support by:

- helping new workers become comfortable with their job responsibilities and workplace.

- answering questions and offering support.

- assisting with problem solving, clinical skills, and handling the emotional impact of their work.

Whānau or family

The whānau of the service user have some responsibilities, including:

- advocating for the service user and making sure they have access to the appropriate services.

- sharing their knowledge about the service user’s life history to explain behaviours and support different treatments and care.

- when necessary, whānau/family may hold a legal responsibility for the service user’s health, finances and property through an Enduring Power of Attorney (EPA).

The Ministry of Justice defines an Enduring Power of Attorney as a legal document which sets out who can take care of your personal or financial matters if you can't.

An essential part of a support worker role is to be able to collaborate effectively with other people and organisations to support tangata and their whānau.

Working well together is not just about getting along with others. It is a far more complex skill that requires you to practice the positive attributes of a team member.

Let's look closely at the descriptions of some of these attributes:

- Communicate constructively. When you collaborate with others your communication needs to be clear, direct, honest, positive and respectful.

- Listen actively. Listening by absorbing, understanding and thoughtfully considering the ideas and beliefs of others. Part of listening is the practice of receiving the information and taking an appropriate time to respond without getting defensive or reacting negatively.

- Be reliable. Keeping your commitments and doing your job to the best of your ability at all times.

- Be willing to share information, knowledge and experience. Being a good, objective source of information, and keeping the healthcare team updated with the latest information.

- Be discrete. A service user's medical information is confidential, and there is no exception. Discuss with tangata, who you can relay and discuss information with to ensure the successful delivery of care and prevent unwanted surprises.

- Be an active participant. Engaging in discussions and meetings and take initiatives to support the service user, their whānau and the healthcare team.

- Be cooperative. Look beyond individual differences to focus on what is best for the person being supported and solve problems or issues in positive ways.

- Be respectful. Consistently act according to your values, be courteous and considerate towards the service user, their whānau and the healthcare team.

Learning checkpoint

The following are communication strategies you can apply in your daily interactions.

Active listening

Active listening skills are key when supporting tangata. Active listening includes:

- clarifying what you have heard

- paraphrasing to ensure you have understood what has been said

- taking time to consider what has been said

Building positive relationships

Building and maintaining positive relationships is possible to greatly reduce or even avoid many barriers to delivering high-quality care under a multidisciplinary team approach. Healthcare organisations with a strategy for establishing and maintaining positive team relationships are more likely to successfully achieve team goals.

The following factors may help to establish and maintain positive relationships within a multidisciplinary team:

- Shared vision. A vision that is shared by all team members so that so that they all want to achieve the goals that they agree are worthwhile.

- Frequent interactions. Regular interactions are a great strategy for team members to collaborate to complete a task. When practised, members of the team are more likely to share and discuss their ideas, opinions, and perspectives. They may also be open to ideas and solutions from outside their own profession or area of focus.

- Trust. When teams frequently reflect on their actions and ways of working, they are more likely to develop trust in one another. This, in turn, can increase team innovation.

- A safe work environment in which teams can express their concerns and frustrations and feel that they are being listened to and that their needs are being met.

Working with tangata and their whānau

As a support worker you need to do more than just work well with the other professionals in your team.

You also need to be able to communicate and collaborate effectively with the service user you are supporting and their whānau.

A service user’s whānau is not limited to the people they are related to by blood. Whānau structures can vary widely depending on the service user, their personal circumstances and who they consider their whānau to be. Whānau could also include a service user’s friends, advocates, guardians or other representatives.

Watch: Building Relationships with Patient and Whānau (3:37 Minutes)

Working with the service user and their whānau in this way means that their needs can be better identified and supported. You can encourage and support others to take an active part in the service user’s care.

Identifying benefits and barriers

Benefits

Think about working with a service user and their whānau with a common goal of high-quality care.

Consider the benefits of working together to achieve this goal.

These benefits could include that:

- the care provided addresses the needs of the whole person, not just particular aspects.

- whānau are up to date with changes in the service user’s condition and are able to talk openly with care providers.

- care can be customised to meet the service user’s individual needs.

- whānau can support goals in the care and rehabilitation of the service user.

- there are fewer complaints about the service, as there is a better understanding between all the people involved in the person’s care.

Barriers

Consider the barriers to working together with the tangata and their whānau that might prevent you from achieving their goals.

These barriers could include:

- possible conflict, if care providers are obliged to follow one path of care delivery and the whānau, want another.

- misunderstandings over different healthcare worker roles and the different viewpoints of these roles.

- disagreement between members of the service user’s whānau over the care that they should receive.

- a relationship between the service user and the support worker that is too close, impacting the support worker’s effectiveness in responding to a change in the person’s condition.

Working collaboratively with a service user and their whānau will not only help to meet their support needs but will also help in establishing and maintaining positive relationships with them. Having a healthy, positive relationship with the service user you support is essential to achieving the goal of providing high-quality care.

Ways you might do this include:

- By providing information: providing information to the service user and their whānau helps them to get a better understanding of the situation and promotes their engagement. Information provided by the service user and their whānau can help you to meet the person’s support needs more effectively. Remember that this communication needs to work both ways– it is important to encourage the whānau to be informative as well.

- By encouraging participation: when whānau participate in the service user’s life and daily activities they can develop and nurture a more positive and meaningful relationship.

- By respecting culture: understanding different cultures and knowing how to work well with them in a health or wellbeing setting is a very important part of your job. This can make a big difference to a service user’s health outcomes.

- By providing advocacy: if there is a conflict involving the service user and their whānau, you can help by escalating the issue to the appropriate team member.

Conflict happens when a person or group of people perceives there is a difference with another person or group, and this results in interference or opposition.

Conflict management strategies

The traditional view of conflict is that conflict is bad and must be avoided.

A more positive view of conflict is that it is natural and inevitable in any organisation. Conflict management aims to harness conflict to achieve positive outcomes.

Finding a common platform can be challenging when a multidisciplinary team is trying to work collaboratively.

All the different views and perspectives that team members bring to the group can be beneficial. Still, differences can also cause gaps, frustrations and conflict.

Causes of conflict

Some issues can cause conflict when working collaboratively within a multidisciplinary team and/or with a service user and their whānau.

Here are some common causes of conflict to consider:

- Breakdown in communication. When people fail to communicate well – or at all – this can often result in conflict. When people have different information or make assumptions about things, this can cause uncomfortable relationships, misunderstandings and even feelings of anger. Breakdowns in communication breakdowns are often unintentional – they can easily happen simply through poor communication habits.

- Differences of opinion. People will not always share the same viewpoint. Conflict can often result when people do not agree on something or on what action should be taken in a particular situation.

- Personal animosity. Animosity is where someone has a strong feeling of dislike for another person, which often has a negative effect on the way they act around or towards them.

- Sexism or racism. Unfortunately, some people have biases and prejudices – they have formed a negative opinion about another person (or persons) because of their gender, ethnicity, culture, etc. Even if they keep their views to themselves, it can slip through in their words and actions. Jokes about gender or race can easily be understood in ways that create offence.

- Inappropriate use of language. Inappropriate language is using spoken or written words that may cause offense. This includes swearing and language that is racist, prejudiced, obscene or disgusting. Different situations may mean that it is fine to use less formal English, but language must always be respectful and professional.

- Breaking the rules. A health and wellbeing organisation's policies and procedures are the principles, rules and guidelines that set out what needs to be done and how to do it. When someone doesn't obey these rules, this can cause conflict with their employer, other team members and the people they support.

Learning checkpoint

Watch: Communicating with Māori in a health setting (5:56 Minutes)

Watch the following video on communication among healthcare staff during a patient's stay in hospital.

These questions are a starting point for reflection. Head to the Forum to add to the discussion in the 1.6.7 Communicating with Patients thread.

- What communication tool worked for Ms Bartlett’s family during the father's stay in the hospital?

- What are some ways health workers can communicate or establish rapport with the service user and their family?

Record your responses privately using the following documentation tool.

- click the questions on the left tab

- or click the next button on the bottom right corner to record your responses

- when you have responded to all the questions, click 'Create Document' on the last tab to export it.