Before we commence with the learning, let’s revisit essential concepts from your level 4 Nutrition module. It's crucial to solidify your grasp of foundational nutritional principles before delving into new knowledge. In this module, we will cover:

- A refresher on your role's scope of practice as a personal trainer.

- The significance of evidence-based information, along with guidance on assessing article credibility and scrutinizing nutritional claims. You'll also learn how to find trustworthy nutritional resources online.

- An in-depth exploration of the Ministry of Health (MOH) guidelines for healthy eating, including a national overview.

- Adapting MOH guidelines to diverse client objectives.

- Application of these concepts across various case study scenarios, ensuring you comprehend their real-world implementation.

Throughout this topic, you will employ diverse learning, using written and video materials, brief quizzes, and case study applications. Notably, this week's learning isn't accompanied by an assessment task. Instead, it's designed to prepare you for the upcoming weeks where related assessment tasks await.

Your scope of practice outlines the boundaries of what you are qualified and legally allowed to do. It helps ensure that you provide safe and effective client services while avoiding legal and ethical issues.

Operating outside of your scope of practice can have serious consequences, including legal liabilities, loss of professional credibility, and risk to client safety. Understanding your scope of practice is crucial to providing quality care, protecting yourself and your clients, and building a successful career in the health and fitness industry.

It is important to always be aware of your professional boundaries when giving nutritional advice to your clients.

Nutritional guidance within professional boundaries

Personal Trainers can provide basic healthy eating information and advice through the application of nationally endorsed nutritional standards and guidelines. For NZ personal trainers this means that nutritional advice given to clients must be consistent with NZ Ministry of Health (MoH) guidelines. It is important that all personal trainers know these guidelines well.

While it might initially appear that your role as a personal trainer imposes constraints on providing nutritional guidance to clients, this is far from accurate. The MoH Nutrition Guidelines, encompassing a wide range of aspects, actually provide ample room for offering advice within the parameters of professionalism. Click on the following headings to find out a variety of ways you can give nutritional guidance within your scope of practice.

Adhering to MoH guidelines.

Explaining food groups and their quantities in a healthy diet.

Comparing with MoH guidelines and recommendations.

Guiding clients in modifying eating patterns.

Aligning with MoH guidelines.

Manipulating macronutrients, intake timing, and portion control.

Compliant with MoH guidelines.

Advising on cooking and food preparation techniques.

Educating clients about label reading and better food selection.

What not to do

Here are some contexts that fall outside of your scope of practice:

- Advising clients to completely eliminate specific foods or food groups from their diet, such as grains or dairy.

- Recommending nutritional supplements to compensate for dietary shortcomings.

- Providing tailored nutritional advice for medical conditions, medications, or potential drug interactions.

- Designing meal plans that deviate from the recommendations outlined in MoH guidelines.

A personal trainer should also take care when discussing the benefits and risks associated with performance-related supplements to ensure they are fully informed and never make recommendations based on personal experience or anecdotal evidence.

These are all contexts in which a personal trainer should refer a client to an appropriate health professional, such as a nutritionist or registered dietician. Having strong connections with these health professionals in your local area should be a focus for all personal trainers. These relationships can often develop into reciprocated benefits for both the trainer and health professional as referrals can be a two-way process.

Clients will often engage in discussions with you about topics that lie beyond your scope of practice. Therefore, it's crucial for you to be well-versed in these areas, even though they may not be within your primary responsibilities. This broad understanding of common nutritional approaches and health-related performance issues is vital for personal trainers. It equips you to provide clients with informed insights on potential courses of action and recommend professionals for further guidance. Remember, this knowledge isn't about delivering specialised advice; it's about skilfully navigating conversations, knowing when to provide guidance, and when to suggest seeking expert input.

Navigating client advice

Giving advice within a defined scope can be tricky. You might ask yourself… “Why can’t I give advice to clients on topics outside the scope if I know what I’m talking about?”

Personal trainers, while possessing valuable knowledge in various areas, are bound by professional boundaries for the well-being of their clients. While you may be well-informed about certain topics, it's essential to understand that providing advice outside your scope of practice can lead to unintended consequences. This is because advice offered within your expertise ensures safety, accuracy, and effective results. Deviating from your professional jurisdiction may inadvertently overlook crucial nuances, interactions, or considerations that specialised professionals are trained to handle. By adhering to the defined scope, you prioritise client safety and ensure that the guidance provided is backed by specialised understanding and experience.

The potential consequences of getting nutritional advice wrong can be severe.

The following is an example of a lawsuit that was filed in America (taken from REPS Australia – Nutrition Advice Within Scope of Practice).

Capati v. Crunch Fitness

A personal trainer allegedly advised his client who was taking prescribed medication for hypertension to take a variety of nutritional and dietary supplements- some of which contained ephedra. Research has shown that the combination of hypertension medication and ephedra can be lethal. While working out at the Club one day, the client became very sick and later died of a brain hemorrhage (stroke) at the hospital.

As a result, the family filed a US $320 million-dollar wrongful death claim against the defendants- the personal trainer, the Club, and a variety of other defendants including Vitamin Shoppe Industries. The case was settled before going to trial, with the personal trainer and the Club liable for US$1,750,000.

Though it may feel frustrating to hold knowledge (beyond your scope of practice) that could benefit a client, adhering to your professional boundaries safeguards you from the potential consequences outlined earlier. However, this doesn't imply that you shouldn't continue expanding your knowledge of nutrition from reputable sources to enhance your understanding of its impact. It signifies that there are experts better equipped to assume the responsibility of offering advice on specialised nutritional approaches that extend beyond MoH guidelines, thereby managing associated risks effectively.

If you would like to be able to offer this type of nutritional advice to clients with assurance, then you should think about further study in this area. This would involve studying to become an accredited practising (registered) dietician or sports dietician.

Review questions

Explore the questions below by clicking on them to reveal the answers and reinforce the essential concepts discussed. Test your understanding before uncovering the answers.

Staying within your scope of practice maintains professionalism and ensures accurate and safe client guidance.

A comprehensive understanding equips personal trainers to provide informed guidance and direct clients toward the best steps forward.

It means offering guidance on topics that align with your expertise, ensuring accurate and effective recommendations.

Personal trainers should be knowledgeable about these areas for informed discussions but refer clients to specialised professionals for detailed advice.

Following your scope of practice ensures that clients receive guidance that is accurate, safe, and supported by specialised expertise.

Personal trainers can enhance their understanding of nutrition's impact without exceeding their scope, leaving specialised advice to qualified experts.

Qualified experts possess the knowledge and training to navigate risks associated with providing advice beyond standard guidelines.

Let’s revisit crucial key points and statements offered by MoH to reinforce your understanding.

Encourage, support, and promote breastfeeding

MoH guideline that highlights the importance of encouraging, supporting, and promoting breastfeeding. This guideline adds another layer of significance alongside the others you've already revisited. Breastfeeding plays a pivotal role in the holistic approach to health and nutrition, and understanding its implications enriches your ability to guide clients effectively. See the following statements from the MoH.

- MoH states that breastmilk is the ideal food for babies and has many benefits for both mother and child. Support helps mothers to breastfeed longer.

- If you have clients who are pregnant or have young babies, do keep in mind that there are many reasons why someone may choose not to breastfeed, or cannot breastfeed. The decision is theirs alone and your role as a PT is to support your client, not judge.

Body weight statement

Moving forward, our focus shifts to another integral aspect of the MoH guidelines: The Body Weight Statement. This statement delves into the considerations surrounding body weight management in the context of health and nutrition.

Making good choices about what you eat and drink and being physically active are also important to achieve and maintain a healthy body weight. A healthy weight:

- will help you stay active and well

- reduces your risk of getting type 2 diabetes, heart disease and some cancers.

To prevent weight gain and lose weight MoH suggests the following:

- Choose nutritious foods that are low in energy (minimal fat and added sugar).

- Drink plain water instead of sugary drinks and/or alcoholic drinks.

- Reduce portion sizes.

- Sit less and reduce screen time.

- Be as active as possible.

For a more detailed breakdown of MoH Guidelines with suggestions for how to implement them, check out the “Eating and Activity Guidelines for New Zealand Adults” here:

In an era of widespread online information, individuals often face the challenge of discerning reliable claims. The abundance of nutrition-related misinformation further complicates matters, leaving the public uncertain about the credibility of various nutritional assertions. Frequently, those who make strong nutritional claims online may be driven by agendas, such as promoting supplements or fad diets. They might also hold biased views, advocating a singular approach like plant-based diets. Alternatively, some may share personal successes without considering broader contexts.

Often evidence-based nutritional principles that have been proven to work time and time again are lost amongst the hundreds of inauthentic messages that the general population is bombarded with each day in the form of mainstream media, social media messaging and advertisements targeting their insecurities.

As personal trainers, you wield significant influence over the public, who rely on your expertise in health, fitness, and nutrition. Just as you place trust in your doctor's counsel, your clients trust your competence in matters of health, exercise, and nutrition. Therefore, it's imperative that the information you share is firmly grounded in evidence-based research. Your clients deserve nothing less than well-substantiated guidance that supports their well-being.

Unfortunately, it is not a simple case of reading a piece of research and passing on the findings to your clients. There are good research sources that offer information that can be broadly applied to the general population. There is also an incredible amount of research that has been conducted on specific population groups or has been conducted to study a very specific effect. Unfortunately, this type of research holds little value for the wider population, so cannot be taken as “fact”.

Luckily, the research departments of government health departments (such as the MoH) are constantly reviewing the research for us. These findings are then compiled into recommendations that serve as a basis for advising our clients.

This highlights why matters beyond a personal trainer's scope of practice are best left to post-graduate level nutrition experts. Attaining this level of education demands an intricate understanding of research- how to interpret it, assess methodologies, and effectively apply findings. This is essential due to the inherent limitations in all research, implying that a successful outcome from a specific nutritional study doesn't automatically warrant its widespread adoption.

Conducting nutritional research is a notoriously difficult task. Particularly research that can be used to advise an entire population. In order for a dietary recommendation to become part of a National Food Policy, research findings must be repeatable and be shown to cause consistent effect over time. And therein lies the problem...

Issues with research in nutrition

To comprehensively examine the effects of a nutritional intervention on people, an exhaustive approach is required—constant monitoring in a controlled environment, overseeing all activities, dietary compliance, and excluding external influences (like exercise). Such stringent control ensures accurate results devoid of confounding variables. However, this method is cost-intensive and often exceeds researchers' budget constraints.

Unfortunately, this means most research can only be conducted over short periods of time. This means we can’t predict any chronic effects. It also means that the most used research approach is to explain the intervention process to subjects and then let them return to their lives with the “promise” that they will strictly adhere to the process. That’s a lot of trust, and let’s be honest, it is very easy to make other food choices when no one is watching.

Another frequently employed approach in nutritional research relies on subject recall. This method involves individuals of diverse demographics, such as different ages, ethnicities, sizes, and shapes, to recall their typical dietary habits or maintain records of their food intake over a specific timeframe. These techniques heavily rely on participants' accurate recall abilities and their willingness to provide honest information. Again, that’s a lot of trust!

Things that can get very complicated when conducting accurate evidence based research are both food and the studied participants. For instance….

Did you know?

The way a food is prepared and cooked can cause dramatic differences in its nutrient profile. The same types of food can also have considerably different nutrient profiles. For example, if a subject has 2-minute noodles on their food list, they could choose between a brand with 2g of fat per packet, or a brand with up to 20g of fat per packet. This makes it difficult to control every aspect of food intake, reducing the reliability of any findings.

In summary, food can be complicated!

Let’s look at the complications of conducting these studies on people.

Individuals exhibit various distinctions, encompassing factors like sex, race/ethnicity, BMI, economic status, metabolic rate, food preferences, exercise habits, and fitness levels. All of these differences could affect how the studied participants approach their eating habits, how their bodies metabolise the food they consume, and the extent to which they can recall their dietary intake. (Vitolins and Case, 2020).

Researchers can’t include all types of people in their studies (mainly due to cost and access), which means many nutrition findings can only be attributed to specific population groups. Add to this that many researchers want to see the effect of the nutrition intervention, so often use unrealistic amounts of a nutrient in their studies, i.e. amounts of a nutrient that would be difficult, or expensive to consume on a regular basis) and you produce findings that have limited relevance to the majority of the population.

All of these limitations with research make it difficult for new nutritional interventions to become adopted under national food policies or guidelines. This is why, those recommendations that have made it into MoH guidelines have been proven to be the best approaches consistently and repeatedly for the majority of the population.

While research possesses its limitations, it remains crucial for enhancing our understanding of nutritional best practices. Of utmost importance is acquiring the skills to access reliable information and, even more significantly, comprehending the nuances of the content you're reading.

An additional issue in getting consistent and accurate messaging around nutrition out to the wider population is that quality (evidence-based) information can be lost amongst an abundance of “anecdotal evidence” supplied by mainstream media reports and social media “experts” and bloggers. Media often report new findings in nutrition in a sensationalised fashion, often reporting only selected parts of the research findings and often out of context.

Media hype: Artificial sweeteners

In June, 2023, mainstream media was a buzz with stories surrounding artificial sweeteners and a link to cancer. Mainstream media were quick to produce news stories (based on research) that told readers and listeners that the diet soda they were drinking was going to give them cancer.

Click the arrows below the image to switch between mainstream media headlines from 2023.

The WHO has raised the carcinogenic rating of some artificial sweeteners from level 3 to level 2b, which means they could possibly cause cancer. Meyerowitz-Katz (2023) gives this decision a little more context when he lists a few other items found on this list:

- Pickled vegetables.

- Aloe vera.

- Coconut oil.

- Talcum powder.

Processed meats feature even higher on WHO’s carcinogen list.

The point is these sweeteners may be weakly associated with cancers, but so are many other daily use household items. The news stories (nor the WHO for that matter) talk about the amount of sweetener that may be risky to consume.

According to the US Food and Drug Administration, the acceptable recommended daily intake for aspartame (the main sweetener indicated in this story) is 50mg per kg of body weight. For a 60kg person, this amount would be found in 19 cans of Diet Coke! This suggests that someone consumes significantly less than this upper limit, would carry a reduced risk of its carcinogenic effect. (Meyerowitz-Katz, 2023). One would also assume that consuming 19 cans of any beverage is likely to have negative consequences.

But what does the research actually say about artificial sweeteners and cancer?

A little more digging reveals that the decision to reclassify these sweetener’s carcinogen levels is mainly due to one large French study completed by Debras et al (2022) who found that those that consumed the highest levels of artificial sweeteners had the highest incidence of cancer. This was a large study conducted on 102,865 subjects who completed 24-hour dietary recalls to supply data. The study was conducted from 2009-2021 and the average participation in the study was around 7-8 years. The authors themselves ended their paper by stating the limitations of the study which included bias of subject selection and the presence of a vast array of other contributing factors to name a couple.

This wasn’t the first study conducted on sweeteners in recent times. Far from it. An “umbrella” review of all the research to date on the effects of the consumption of artificially sweetened beverages was produced by Diaz et al (2023). This review included data from 11 meta-analyses, 7 literature reviews, 51 population studies, and case-controlled studies.

The authors concluded that artificially sweetened beverages were associated with a higher risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes, all-cause mortality (death), hypertension, and cardiovascular disease, but that evidence for other negative health incomes (colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, gastro-intestinal cancer, all-cancer mortality, cardiovascular mortality, chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease, and strokes) was weak.

In conclusion, while artificially sweetened drinks might not offer significant health benefits, the likelihood of them causing cancer seems to be minimal. Additionally, the authors emphasise that none of the conducted research indicates the specific consumption volume of these beverages that could lead to the adverse effects highlighted in the review.

While evidence of artificial sweeteners causing cancer is, at this stage, very weak the mainstream media was very quick to sensationalise this link, which in turn leads to the general population making snap decisions on their consumption of these drinks.

Yes, we know that everyone would be better off simply drinking water, but we also know that that is not human nature. People want their sweet fix. If these news stories lead to people deciding to switch back to sugar-sweetened beverages to avoid getting cancer, then we have a raft of new issues as high sugar consumption has an even stronger link to not only cancer, but most other negative health outcomes.

Two-sided confusion

Regrettably, the perplexity surrounding nutritional claims isn't solely attributed to media influence. At times, even the research itself contributes to bewilderment. When the public is presented with contradictory information from research, confusion arises, compelling individuals to independently decide whether adjustments to their dietary choices are necessary. This dilemma is compounded by the likelihood that individuals may opt for what they wish to believe, potentially resulting in significant repercussions.

Media hype: Red and processed meat

In the past decade, research has spotlighted apprehensions regarding excessive consumption of red and processed meat, associating it with an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer. Consequently, individuals have been urged to curtail their weekly red meat consumption. Aligning with WHO recommendations, our Ministry of Health Guidelines advocate a weekly red meat intake not exceeding 500g. However, some recent research claims that this risk has been overstated and that there is only weak evidence to suggest that red meat consumption contributes to any negative health outcomes. The media of course jumped on this because this would be something the public would love to hear.

Click the arrows below the image to switch between mainstream media headlines from years 2019 and 2022.

How did you go, did you guess correctly for all statements? All of these statements are commonly believed, have been reported in mainstream media and are commonly discussed as “facts” in online articles despite there being little to no evidence for some of them. So, how can you tell what is good information and what is not?

How to read nutritional claims with an analytical eye

Registered Dietician Nancy Ernst (n.d.) has a few useful tips (red flags) for how to spot dubious nutritional information. See the following table.

| Does it sound too good to be true? It probably is! | No single nutrition product or food can completely cure a chronic health condition, or provide immediate or dramatic relief of condition symptoms. |

|---|---|

| Testimonials. | Testimonials mean nothing when it comes to nutrition approaches! Only the results of carefully controlled scientific experiments count as evidence of a nutritional intervention's effectiveness. |

| The claim is made that everyone can benefit from this nutritional intervention. | If this was true, it would be part of the National Food Policy. |

| The person promoting the nutritional approach also stands to benefit from the sale of the nutritional approach. | Credible theories in nutrition are made available to all who know where to find them (research). While medical and nutrition specialists may recommend an approach or product, they don’t profit by selling them. You can almost guarantee that if a person is trying to sell you something, they will be selective in the evidence they include. They certainly will not supply any evidence that might discourage you from buying the product. |

| Is a product being promoted as a “natural” stress reliever, or claim that it will “detoxify”, “revitalize” or “purify” your body. | Your liver does this really effectively; a product will not do this for you. In fact, the “natural product” will also be processed by your liver. |

| Does a dietary approach or product promise that weight-loss will be effortless, immediate, or guaranteed. | The only way to lose weight and keep it off is to reduce calorie intake or increase calorie expenditure. While eating less and moving more are realistic goals, they do not elicit immediate results and are approaches that many people find difficult to adhere to consistently. |

| Check the author’s details. | First, look for the author of the information and check their credentials. Ideally, the author should be a registered or clinical dietitian or nutritionist. If the person making the nutritional claim has no recognised qualification in the field of nutrition, then treat the information warily (and yes, this even includes claims made by medical professionals). Look for nationally accredited qualifications and professional credentials in the field of nutrition. |

| Check the website details. |

If there is no author listed, make sure the website the information comes from is a quality source. Well-known institutions like universities, or government (health) websites can be great sources of information but may not include individual authors. These websites will usually end in .edu, or .gov(t). Avoid using information from .com (commercial). These websites often have an agenda (e.g. to promote a particular product or service) rather than educate a consumer. Websites ending in .org (organisation) can be good sources of information, although may be special interest groups with a particular bias, meaning that only part of the research is discussed. Approach these websites with a critical eye. |

| Has the article the claim appears in been “peer reviewed”. | This means that other appropriately qualified people have read these claims and agree that there is sufficient evidence to support them. |

The following article is an example to show you just how skewed “evidence” can be.

This article, published in the UK Daily Mail in March of 2015 entitled “A Glass of Wine is The Equivalent to an Hour at the Gym, Says New Study”

Have a read of the article in full:

A Glass of Wine is The Equivalent to an Hour at the Gym, Says New Study

Love a good glass of vino but hate hitting the gym to work it off? This news will make your day. Research conducted by the University of Alberta in Canada has found that health benefits in resveratrol, a compound found in red wine, are similar to those we get from exercise.

Red wine over a heavy session on the cross-trainer? Now that's something we can definitely get on board with. According to lead researcher, Jason Dyck, these findings will particularly help those who are unable to exercise. Resveratrol was seen to improve physical performance, heart function and muscle strength in the same way as they're improved after a gym session.

"I think resveratrol could help patient populations who want to exercise but are physically incapable," he says. "Resveratrol could mimic exercise for them or improve the benefits of the modest amount of exercise that they can do."

Discussion over the health benefits of red wine have been well documented. Studies have revealed that those who drink a glass of red wine a day are less likely to develop dementia or cancer, that it's good for your heart, anti-ageing and can regulate blood sugar. And now there's research backing that fact that it boosts heart rate? This is literally the best thing ever.

Though, let's be straight here - this is all in moderation, it only applies to red wine and the university's study was carried out on rats, not humans.

Still, if you want to up your intake of resveratrol? Try blueberries, peanut butter, red grapes and dark chocolate. Remember, a balanced diet is everything.

Right...even the most optimistic of you out there must have a nagging feeling that this is a little too good to be true.

Let’s apply Registered Dietician Nancy Ernst’s useful tips (red flags) to see how many flags you can identify.

Click each to reveal if you are on the right track.

Red flag alert!

N/A- no testimonials.

Red flag alert!

Although the article does mention it will be particularly beneficial for those that can’t exercise.

N/A- No, it wasn’t funded by a wine company!

N/A

Red flag alert!

Yes. Drinking wine is pretty effortless! An hour at the gym should help with weight loss. The title of the article says it “is” the same as an hour at the gym (not it “may” be the same).

Red flag alert!

This was written by a staff reporter from the Daily Mail.

Red flag alert!

Not from a reputable organisation.

Red flag alert!

No evidence that anyone has fact checked this article.

Red flag alert!

The article does include quotes from the lead researcher and there is mention of a study, but links are not provided.

This is a total of seven red flags using the quality check principles discussed. This gives you a pretty good idea that you should proceed with caution with the information found in this article. The article refers to a genuine research study that was conducted, but we have no idea if the findings of this research actually suggest that a glass of red wine equates to an hour at the gym, or whether the author of the article has drawn his own conclusions. Let’s find out!

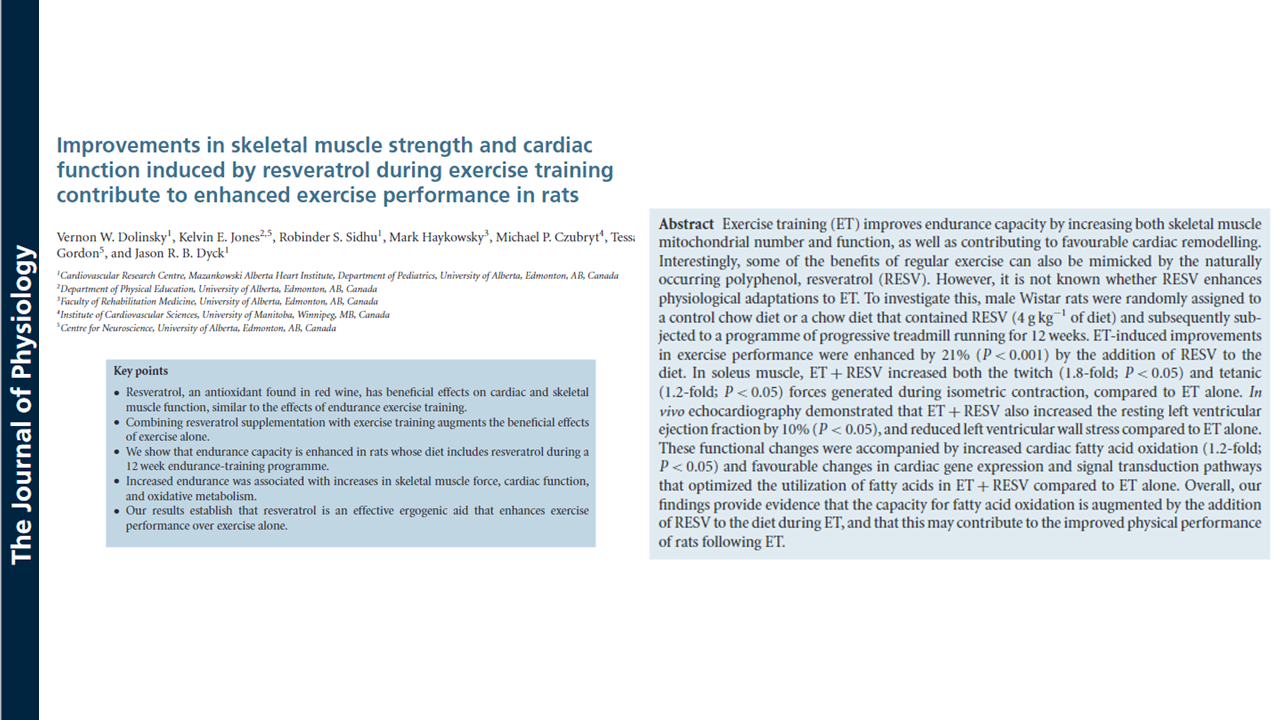

A quick online search using the title of the article (supplied in the newspaper story) and the author’s name allowed me to find the original study article. Here is the front page.

This study was published in a reputable journal (the Journal of Physiology). However, a quick scan of the title tells you that this study was about resveratrol (not wine), that it was conducted on rats (not humans), and that Jason Dyck was not the lead researcher (his name is at the end of the list of authors).

Here is a quick run-down on the methodology used in the study by Dolinsky et al (2012):

- 50 rats were used in the study. Half were on a normal "chow" diet. The others had a diet higher in resveratrol.

- The rats performed daily bouts of aerobic endurance exercise. 60 minutes of increasing intensity treadmill running (stimulated by administering shocks through feet if they stopped). Rats achieved exhaustion in each session.

- Rats trained 5 x weekly

Here is a quick overview of the findings of the study by Dolinsky et al (2012):

After 12 weeks of Exercise Training (ET) the rats on the high-resveratrol diet:

- Were able to run longer and further than rats that were only subjected to ET.

- Had higher O2 consumption and use of fatty acids as a fuel source. This was particularly increased in the cardiac muscle.

- Had increased left ventricle output by 10% more per beat.

Here are the author’s conclusions:

"Resveratrol optimizes fatty acid metabolism, which may contribute to the increased contractile force response of skeletal muscles and improved parameters of cardiac structure and function. As such, these RESV-induced adaptations are likely to contribute to the improved endurance capacity of ET rats and we conclude from these findings that dietary supplementation of RESV during exercise improves exercise performance beyond exercise alone. This strategy may have clinical utility in many situations where improved physical performance needs to be augmented due to the patient's inability to perform intense exercise.”

Summary

This study found some promising results (for rats) in terms of adding resveratrol to the diet in conjunction with intense exercise. The authors then concluded that this may have some benefit to those who for some reason cannot perform intense exercise. There are a couple of problems with this conclusion:

- All of the rats in the study were subjected to intense physical exercise (to exhaustion). This means that it is difficult to separate the effects of resveratrol from exercise. In no way do the findings of this study tell you that resveratrol alone will elicit the effects discussed. That means it is a stretch for the authors to even suggest that resveratrol may be useful for people that can’t do intense exercise because all of the rats were exercised to exhaustion in the trial.

- The journalist who wrote the newspaper article implied that anyone could get these benefits by consuming wine (and not exercising). The rats were not given wine, they were fed resveratrol mixed in their food. That rats performed significant bouts of exercise!

- At no point did the authors of the original study suggest that resveratrol could replace exercise. The reporter made that conclusion themselves.

The reporter made the leap to wine consumption. This is because resveratrol is found in red wine. But how much resveratrol were the rats fed in the study, and how much wine would that equate to?

- In the study, the rats were fed the equivalent of 146 mg resveratrol/kg per day.

- Let’s say a person weighs 70kg. 70kg x 146mg of resveratrol = 10,220mgs (or 10.2g)

- A glass of red wine contains between 0.3 and 1.07mg of resveratrol.

- This means a 70kg person would have to drink around 9000 glasses of red wine to achieve the dose of resveratrol used in the study (which I'm sure will negate any benefit!).

Unfortunately, this is a common theme in many scientific experiments targeting nutritional supplementation. The doses found in supplements are often hard to translate back into real food, meaning that an unrealistic amount of a particular food needs to be consumed to elicit the proposed benefits.

The provided example illustrates an extreme case of how the outcomes from valid research can be misinterpreted before reaching the general public. Applying quality checks is an excellent method for deciding if further investigation into the research is necessary before conveying nutritional discoveries and assertions to your clients. To accomplish this effectively, it's important to enhance your confidence in accessing and comprehending scientific journal articles.

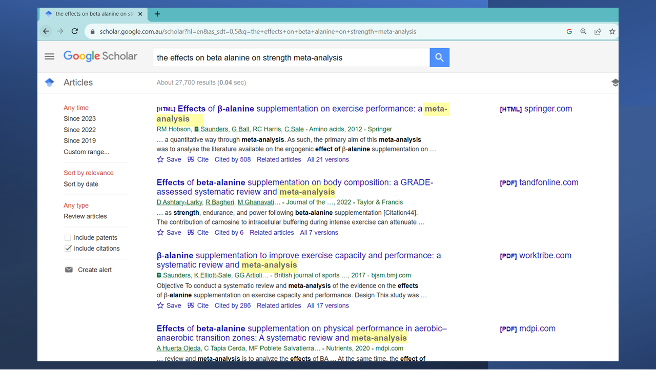

Introducing Google Scholar

It is important to get comfortable accessing information from quality sources. The internet is a treasure trove of information. In years gone by, trainers would have had limited access to quality sources of information as they were generally only to be found in universities or public libraries. The internet is now full of online databases that hold research articles in electronic form.

Some publications require a membership that requires a subscription, but many reputable journals release their articles to the general public via research portal sites. A Google search for evidenced-based information will likely yield an abundance of articles of various reputability. Luckily, Google has provided a search engine tool that weeds out most of the fluff and allows you to home in on higher quality sources of information, Google Scholar.

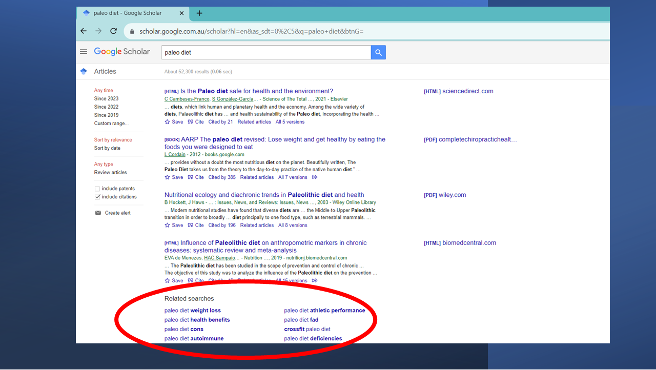

Google Scholar refines your search to include only scientific publications. The wording you use in your searches for information can be broad or very specific depending on the information you wish to find. For example, if you wanted to know more about the Paleo diet, you could simply enter “Paleo diet” in the search box. However, if you were only interested in finding out the risks associated with the diet, you would be better to search for “paleo diet risks”. Google Scholar is also quite helpful in suggesting related searches you might be interested in. You can find these towards the bottom of the first page of the findings.

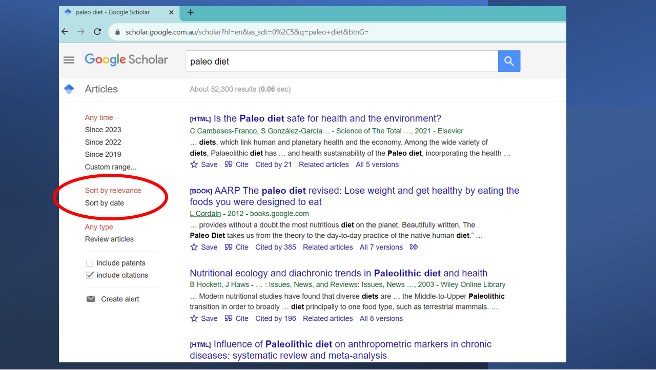

Wherever possible you should always try to get the most up-to-date information possible. Science is always changing as new technology emerges allowing us to find out new information that wasn't available even a few years ago. Google Scholar can help you with ensuring your articles are as up-to-date as possible.

Just click the "sort by date" link on the left-hand side of the search listings.

Note: This can mean the articles listed lose a little relevance, so you may need to refine your search wording.

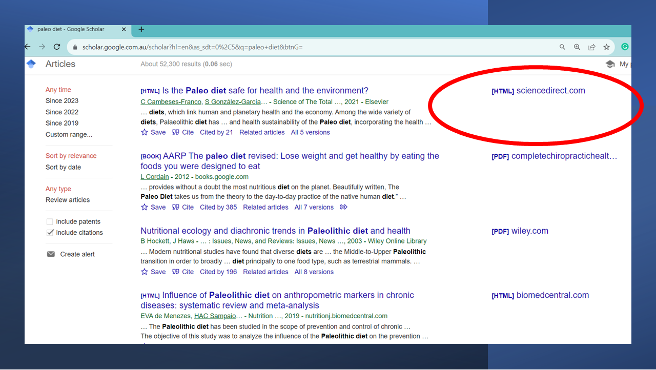

Abstracts vs full articles

Most publications won’t simply give away all their articles for free. However, every scientific journal article begins with an “abstract”. An abstract is a short synopsis of the research article that tells you the purpose of the study, the methods used, the results, the key discussion point and the conclusion. The abstracts of published scientific articles are available for free online. Abstracts are a useful way of finding out whether an article is worth reading. If access to the full article is free, then a link is usually shown on the right-hand side of the google scholar search screen. Alternatively, when you are reading an abstract, there will often be a “full-text links” or “Download PDF” button in the top right of the screen.

Literature reviews and meta-analyses

While individual studies are great to read and can yield some interesting information, the best articles to access when searching for evidence-based research are literature reviews and Meta-analyses. These articles collate all the research they can find on a topic. They work through each article and then remove any studies that have serious limitations or methodological concerns. Once they have narrowed the articles down to those with excellent methodologies, they read and summarise the findings collectively. This allows you the benefit of reading a summary of all the quality articles that cover the topic you are interested in. These review articles end by summarising and re-stating the key findings. The beauty of gaining your information from these articles is that you know someone more qualified than you has analysed each article and drawn appropriate conclusions. You should always attempt to find the most recent review article possible to make sure any new evidence has been included.

While Google Scholar doesn’t yet offer a filter to support searches of only literature reviews and meta-analyses, you can simply enter the words to the end of your search, and it will often yield a result.

Tune into the following short video explains how to navigate the Google Scholar search engine.

How to read a scientific article

Finding an article is one thing, being able to read it is another entirely. This next short section is designed to help you navigate your way through an article to find the information you are looking for.

All journal articles that present a scientific study are formatted in the same way. Each article is broken into the following sections:

- Abstract: A concise summary encompassing all components of the article.

- Introduction: This section establishes the study's purpose and provides contextual background by referencing prior or related research. It also introduces essential concepts that readers should grasp before delving into the study's findings.

- Methods: Detailed elaboration of the experimental design for the current study, coupled with information about the study's participants (e.g., age, gender).

- Results: Comprehensive presentation of all study outcomes, often supported by visual aids like diagrams and graphs. This section is data-focused and generally lacks contextualisation or discussion.

- Discussion: Authors analyse the results, placing them in context and potentially comparing them to findings from previous studies on similar topics. These sections often include “practical applications” for how people in the industry might apply this new knowledge.

- Limitations: This segment may be standalone or incorporated within the discussion. Authors identify concerns about experimental methodology, procedures, or participant selection that could influence the results. Any conflicts of interest potentially biasing the results are also disclosed. For example, if a hydration study was funded by Gatorade and concluded that Gatorade was the best sports drink for replacing electrolytes, this would be a conflict of interest.

- Conclusion: Authors summarise their findings and propose directions for future research inquiries.

Reading literature reviews and meta-analyses

The layout of these articles is slightly different as no scientific experiment has been carried out. These articles typically include:

- An abstract.

- Introduction/background.

- Methods – however this simply details how they selected the studies to be included in the review.

- Data analysis – a compilation of the key methodology and subject data from each of the articles included in the review.

- Statistical Analysis and Results – a collation of results from the studies usually grouped according to measures and findings.

- Discussion – usually split into the different variables/measures included in the range of studies

- Potential confounding factors and limitations.

- Conclusions and recommendations.

Try it out

How well can you collect data? Practice navigating a scientific journal article.

Read this article published in the Journal of Physiology, then answer the questions that follow.

Areta et al's (2013) study aimed to investigate the influence of the protein ingestion method after resistance training on muscle fibre protein synthesis (growth).

Instead of reading the entire article, attempt to answer the questions by navigating to the relevant section of the article and skim-reading until you locate the information you're seeking.

You can check your answers by clicking on each question. No cheating!

24

4-6 hours

3

20g

80g

3

2 years

Vastus Lateralis

Leg extension

Whey

- 8 x 10g serves every 1.5 hours

- 4 x 20g serves every 3 hours

- 2 x 40g serves every 6 hours

70-80kg

No

Great work! Now you have the skills to recognise red flags associated with online nutritional claims. You can now also access quality research material and know how to navigate your way through a journal article to find the information you are looking for. Now you have these skills, you have the ability to access a wealth of information to build your nutrition knowledge.

Let’s have a look at how we are doing as a nation when it comes to meeting our New Zealand (NZ) nutritional needs. The information and statistics shared come from the MoH Eating and Activity Guidelines for NZ Adults (2020) unless otherwise stated.

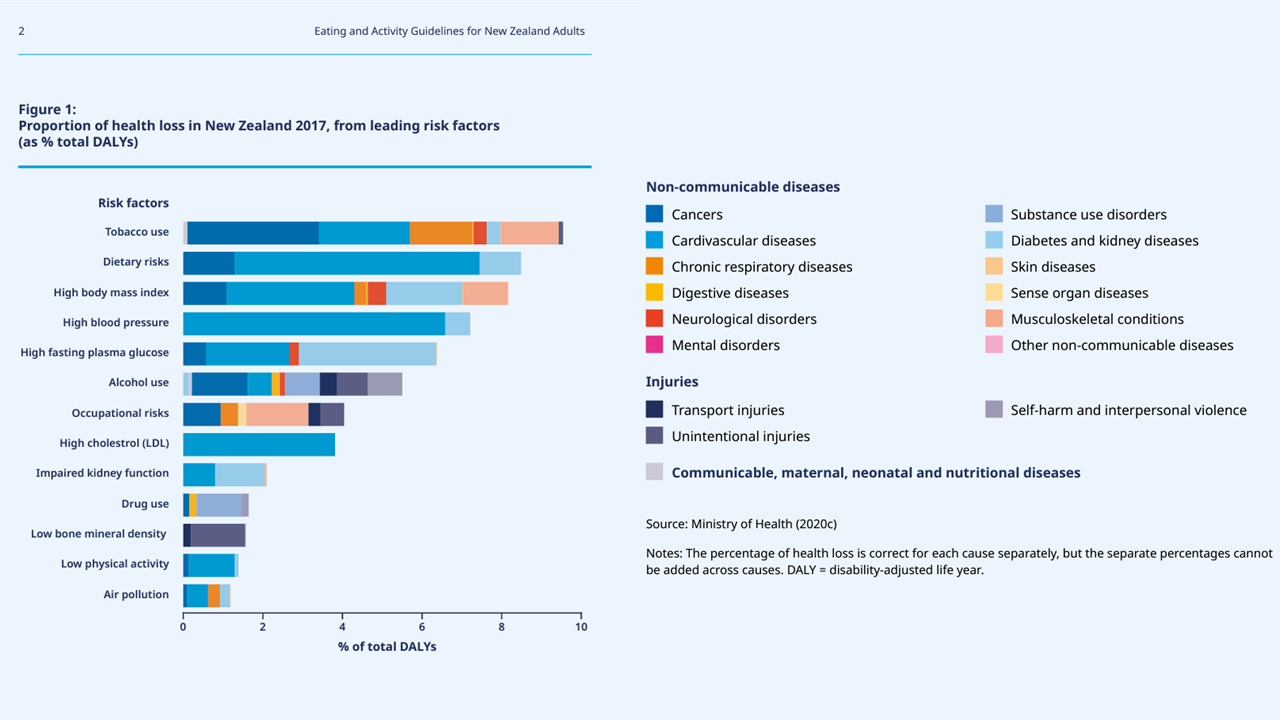

The following image provided by the MoH shows the importance of getting dietary practices right in order to decrease the risk of a number of common health complaints, illnesses, and diseases. What becomes apparent quickly on looking at the image below is that out of all the things that contribute to poor health, the things that we eat, drink and smoke are the leading contributors to poor health in New Zealanders.

If we put aside the issue of smoking (which tops the list), issues either stemming directly from poor dietary habits or indirectly resulting from poor dietary habits make up 6 of the top 8 places on the list of risk factors leading to health loss in NZ.

These nutrition-related issues include:

- Dietary risks (i.e. poor dietary intake).

- High body mass index (overweight or obesity).

- High blood pressure (in which diet is often a key player).

- High fasting glucose.

- Alcohol use.

- High cholesterol.

Several other factors may contribute to the emergence of health disorders. However, it's evident from this compilation that an individual's dietary behaviours exert a significant impact on health results. Consequently, providing high-quality nutritional guidance to all individuals in New Zealand becomes essential for the nation's enduring health outcomes. This is precisely the area where health and fitness experts hold a crucial responsibility.

While the MoH guidelines have been around for years, it appears that the message is not getting through to New Zealanders in a way that will cause meaningful change. According to the NZ Health Survey conducted by the MoH in 2020/21, obesity rates in NZ adults are still on the rise with current obesity rates at 34.3% (up from 31.2% in 2019/20).

It appears adult women have shown a significant rate of increase in obesity over the last 2 years when compared with men with a 4% increase in obesity rates during this time period. Child obesity rates have also risen from 9.5% in 2019/20 to 12.7% in the latest survey. This indicates strongly that we as a country are moving in the wrong direction with our nutrition practices and that if this continues, we will see an increase in the poor health outcomes listed in the image above.

These statistics also reinforce that a large proportion of New Zealanders would benefit from further education relating to MoH guidelines. It also suggests that the more extreme or radical dietary approaches often discussed in online articles and blogs are redundant given that a large proportion of the NZ population don’t adhere to basic nutritional guidelines. Let’s take a closer look at some of our main dietary issues in NZ related to each of our main food groups.

It's quite evident that adherence to MoH nutritional guidelines among New Zealanders is currently not at its best. To better understand our situation, let's take a moment to delve into the MoH recommendations once again and discuss how our nation is faring in terms of aligning with these guidelines. This analysis will provide valuable insights into the state of nutritional practices across the country.

MoH: Statement 1- Eat a variety of nutritious foods every day

This statement focuses on ensuring people are enjoying a range of nutritious foods every day that includes:

- Fruit and vegetables.

- Whole grains.

- Milk and milk products.

- Protein.

Fruit and vegetables

Eat plenty of fruit and vegetables. Vegetables and fruit provide important vitamins, minerals, and dietary fibre. They have been proven to help prevent excess weight gain due to their low-calorie/high-fibre composition. They have also been proven to protect the body against diseases such as heart disease, stroke, and some cancers.

MoH guidelines suggest that the majority of vegetables eaten should be non-starchy, however, potatoes, kumara, and taro continue to be staple vegetables in many NZ households. While these starchy vegetables have limited amounts of micronutrients, they are typically dense in carbohydrates, so should be eaten in moderation.

The latest MoH Guidelines propose raising the daily vegetable intake recommendation from a minimum of 3 servings to a minimum of 5 servings per day.

Fruit serving suggestions remain at 2 per day. In fact, the suggested number of servings of vegetables varies depending on gender and age. Here are the latest recommendations from the MoH. The key things to note are that men should be eating an additional serving than women and that lactating women require an increased number of servings.

See the following table that depicts the recommended amount of fruit and vegetables per day for people of different ages.

| Age | Vegetables | Fruit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 19-50 | 6 | 2 |

| 51-70 | 5.5 | 2 | |

| 70+ | 5 | 2 | |

| Women | 19-50 | 5 | 2 |

| 51-70 | 5 | 2 | |

| 70+ | 5 | 2 | |

| Pregnant | 5 | 2 | |

| Lactating | 7.5 | 2 |

As of 2018/19, approximately 50% of New Zealanders ate the recommended quantities of either vegetables or fruit, and only 33% ate the recommended amounts of both.

There are many factors that play into the lack of vegetable consumption in NZ. There is a perception that fresh produce in NZ is expensive and at certain times of the year, this is a very valid point. However, there are plenty of frozen and canned options for vegetables that stay cost effective year around and these have been shown to have equal nutritional value when compared with fresh versions. But there may also be something else that is driving the cost of certain vegetables higher and that is a lack of supply.

NZ produces far more than enough vegetables than is required for every one of us to meet our daily requirements. Harvie (2021) reported that NZ grows the equivalent of 11.7 servings of vegetables per member of the population a day. However, we appear to be growing the wrong vegetables. The equivalent of 7.7 serves per person per day come in the form of potatoes, onions, carrots, and squash (with potatoes making up 4.5 serves per person, and 2.7 servings of those as chips and fries). When these few vegetables are excluded, the production of all other vegetables would provide around 2.9 servings per person per day (Harvie, 2021).

Two areas of real supply concern are vegetable groups that should be part of everyday intakes – Legumes and green leafy vegetables. Legumes include peas, beans, chickpeas, and lentils, and leafy greens are things like spinach, kale, Bok choy, lettuce, silver beet, etc. For each person in NZ to receive 1 serve of these types of vegetables, the production of these would have to increase 76% for legumes and 3811% for dark leafy greens.

In short, there are not enough to go around. The reason why this shortfall in the production of certain vegetables exists is a simple supply and demand issue. We as a country eat a lot of potatoes, therefore the industry supplies a lot of potatoes. But why is it important to eat a range of different fruit and vegetables rather than the same ones over and over?

Watch the following video that explains how eating a "rainbow" of fruits and vegetables get benefit your health.

Fruit and vegetable intakes are the lowest in lower socioeconomic families. This is because these families prioritise being full over being healthy (Martin, 2019).

Tips to support your clients

Here's a valuable tip to enhance your client's nutritional journey:

- Emphasise the numerous benefits of incorporating regular servings of vegetables and fruits into their diets. Guide them towards affordable choices that align with the recommended intake.

- Beyond just potatoes, encourage the exploration of frozen and canned options, especially during periods of fluctuating vegetable prices. Highlight the importance of embracing a vibrant spectrum of colours in their fruit and vegetable choices, explaining the health advantages of such diversity.

- Address a common perception that consuming five vegetable servings daily is challenging. Bridge this gap by educating clients about what constitutes a serving size – often as simple as half a cup.

By doing so, you're empowering them to seamlessly achieve their daily nutritional goals.

Whole grains

Eat grain foods that are mostly whole grains and naturally high in fibre. Eating whole grains and high fibre grains is associated with lower risk of cardiovascular disease, type two diabetes, weight gain and some cancers (especially bowel cancer).

Whole grain and high-fibre grain foods provide energy (mainly from carbohydrates but also some protein), dietary fibre, vitamins including B group vitamins (except B12) and vitamin E (found particularly in wheatgerm), and minerals, such as magnesium, calcium, iron, zinc, and selenium.

Grains are generally affordable and easily available foods that give people some of the nutrients they need. Whole grains and those high in naturally occurring fibres provide better health benefits than more refined grains. Refined grain products have had most, or all, of the bran or germ components of the grain removed (e.g. White flour products, white rice, and pasta). They provide lots of calories, but little nutritional benefit and can raise blood glucose rapidly leading to storage of unwanted body fat.

Watch the following video that compares the contrast the difference between whole grains and refined grains.

See the following table that depicts the recommended amount of grain food per day for people of different ages.

| Age | Grain Foods | |

|---|---|---|

| Men | 19-50 | 6 |

| 51-70 | 6 | |

| 70+ | 5.5 | |

| Women | 19-50 | 6 |

| 51-70 | 4 | |

| 70+ | 3 | |

| Pregnant | 8.5 | |

| Lactating | 9 |

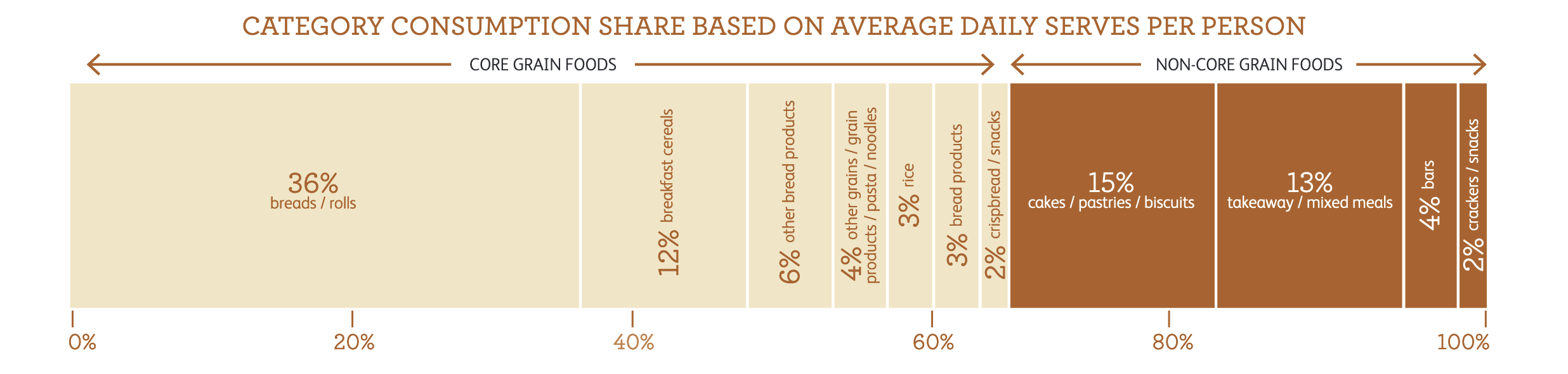

While the majority of New Zealanders meet their grain serve requirements, many still get the majority of their grain serves through bread consumption. The bread we are choosing to eat as a nation is still heavily favouring more refined grain options like white (30%) or light grain (50%). Only 10-14% of NZ adults are consuming heavy grain breads (which contain the most whole grains).

Men tend to eat more grain serves than women. Women are more likely to avoid grain foods, but also appear more conscious of choosing wholegrains that refined grain products (Nutrition Foundation NZ).

The image below shows how NZ people choose to consume their grains. As you can see the majority of grains are consumed as bread. The next highest consumption is in the form of cakes, pastries and takeaway foods (all highly refined). Cereals make up 12% of intake (a mix of refined and whole grain). While many New Zealanders eat the suggested 6 serves of grains a day, less than 50% of all adults consume 3 serves of mainly wholegrain foods a day. This suggests that despite widespread knowledge regarding the health risks of too many refined grains, as a country we still have a way to go. (Nutrition Foundation NZ). These food choices are reflected in the daily fibre intakes of NZ adults which show that the average daily fibre intake of a New Zealander is a third under the daily recommendation for good health.

Tips to support your clients

Here's a valuable tip to enhance your client's nutritional journey:

- The best approach is to reiterate the associated health benefits of choosing wholegrain options over refined grains.

- Provide clients with meal and snack replacement ideas that prioritise wholegrain choices for bread and snacks.

- Emphasise the importance of consuming grains before engaging in physical activity.

- Assist clients in deciphering nutritional labels to avoid refined grain foods that are also high in sugar and fat.

By offering these insights, you can guide your clients towards better dietary choices and improved health outcomes.

Milk and milk products

Eat some milk and milk products (mostly low and reduced fat). Milk and milk products are highly nutritious and contain protein, vitamins and minerals. Specific vitamins include riboflavin, vitamins A, D and B12, while minerals include calcium, phosphorus, zinc and iodine. Be aware that milk products and cheese contribute saturated fat to the diet. The MoH recommends that adults choose mainly low- and reduced-fat milk and milk products to reduce their intake of saturated fat and total energy (kilojoules).

Low fat dairy options are those that contain less than 1.5g (or less) per 100mls of liquid, or less than 3g of fat per 100g of solid food product. Most cheeses are high in fat (most of it saturated). For example, mild cheddar cheese has 35-40g of fat per 100g (24g of saturated fat), but there are other types of cheese with less fat including Edam (27g), Camembert (22%), Feta (20%) and Ricotta (11%). Butter, cream, and products like cream cheese and sour cream are also high in fat and low in protein and calcium.

Plant-based milk alternatives made from soy, rice oats or nuts provide options for those who can’t process lactose well. These alternatives are not naturally as high in calcium and other nutrients (B12 and riboflavin), so consumers should choose products fortified with these micronutrients).

About 50% of New Zealanders are choosing reduced fat or trim cow’s milk options. Those that are the least likely to choose low-fat dairy options are younger adults, men, Maori and Pacific, and those in the lower socioeconomic bracket.

See the following table that depicts the recommended amount of milk and milk products per day for people of different ages.

| Age | Meat and meat products | |

|---|---|---|

| Men | 19-50 | 2.5 |

| 51-70 | 2.5 | |

| 70+ | 3.5 | |

| Women | 19-50 | 2.5 |

| 51-70 | 4 | |

| 70+ | 4 | |

| Pregnant | 2.5 | |

| Lactating | 2.5 |

Based on a national survey conducted in the early 2000s, Smith and Signal (2009) revealed that recommended intakes for dairy were not being met by a significant number of the population. The survey showed that only 38% of NZ children were consuming milk daily and 34% weekly. 17% of children reported they either never drank milk or drank it less than monthly. The prevalence of inadequate dietary calcium in this group was 15%.

Milk consumption was also low amongst young adults with the survey showing that 9.4% of New Zealanders aged between 16 and 30 years of age did not drink milk and 33% of this age group consumed less than one glass a day. Non-consumption was also found to be higher in women than men. The number of adult New Zealanders with deficient calcium intake at this point in time was estimated at 20% of the population (Smith and Signal (2009).

While this data is a little dated, recent data from Statista NZ (2023), suggests consumption of milk by the NZ population continued to decline from the early 2000s right through until 2021 when data collection for this metric ended. This suggests that dairy consumption issues are likely to be at least the rate they were in 2009.

In a worrying comparison to the above figures, through the same period of time that milk consumption was dropping, the consumption of sugary beverages in our population was rising at an alarming rate. Smirk et al (2021) reported the following sugar-sweetened beverage consumption rates in NZ school-aged children:

- 96% drank at least 1 sugar-sweetened beverage a week.

- 62% drank over 5 sweetened beverages a week.

- 40% of total sweetened beverages were soft drinks, while juice contributed 46%. The highest number of consumers were from lower socioeconomic groups and non-NZ European groups (Smirk et al, 2021).

- 16% of men and 8% of women drink 3 or more soft or energy drinks a week, while 37% of NZ adults drink fruit juice three or more times a week.

Tips to support your clients

Here's a valuable tip to enhance your client's nutritional journey:

- Begin by reminding clients, especially those in the older and younger age groups, about the advantages of incorporating lower-fat dairy products into their diets.

- Highlight the significance of these choices for maintaining bone health and supporting muscle contraction, which is crucial for exercise.

- Advocate for reducing the intake of sugary beverages and promote the consumption of water and low-fat milk instead.

- Provide clients with practical suggestions, such as sharing recipes for nutritious smoothies, to help them meet their daily dietary needs in a flavourful and healthful way.

Protein

Eating patterns that include legumes, nuts, fish and other seafood are linked with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, weight gain, and some cancers. Legumes, nuts, and seeds are rich in nutrients and high in fibre and are a source of protein. Some types of nuts are useful sources of specific nutrients for example, almonds provide calcium and Brazil nuts provide selenium.

Nuts are high in unsaturated fats, but eating a small amount (around 30 g) each day should not cause excess weight gain, especially if you eat them instead of other, less healthy foods.

Fish and seafood are good sources of iodine. Oily fish such as salmon, tuna, mackerel and sardines and some seafood like mussels are good sources of omega-3 fatty acids. Omega-3 is linked with a lower risk of heart disease and stroke.

Eggs provide useful nutrients and can be part of a healthy diet for adults in general. Poultry (e.g, chicken) is a good source of protein and some minerals, including iron and zinc. Poultry has a variable fat content depending on the type of bird, but as most of it occurs in and around the skin, it is easy to remove. Red meat is an excellent source of key nutrients like iron (in an easily absorbed form) as well as zinc. Low iron levels are a problem for some New Zealanders, particularly young women.

The World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) reports that eating more than 500 g of cooked red meat (equivalent to 700–750 g when raw) each week is linked with a higher risk of colorectal cancer. Eating processed meat (e.g., salami, bacon, ham, and luncheon) is also linked with a higher risk of colorectal cancer. In addition, processed meats can be high in fat and salt.

See the following image that depicts the recommended amount of legumes, nuts, seeds, fish, and other seafood, poultry, or red meat with fat removed per day for people of different ages.

| Age | Legumes, nuts, seeds, fish & other seafood, eggs, poultry or red meat with fat removed |

|

|---|---|---|

| Men | 19-50 | 3 |

| 51-70 | 2.5 | |

| 70+ | 2.5 | |

| Women | 19-50 | 2.5 |

| 51-70 | 2 | |

| 70+ | 2 | |

| Pregnant | 3.5 | |

| Lactating | 2.5 |

The results of the last adult nutrition survey conducted by the MoH showed that 42% of NZ adults ate fresh or frozen fish and other seafood at least once a week (29% of this was canned fish). 60% of adults ate red meat at least three times a week (males eat more than females), and 85% of adults ate chicken at least once a week. Only 27% of our adult population ate nuts in some form (with only 7% coming in whole nut form and the same amount in peanut butter). Most nuts were consumed in “hidden form” (i.e., hidden in other foods like sauces and baking products).

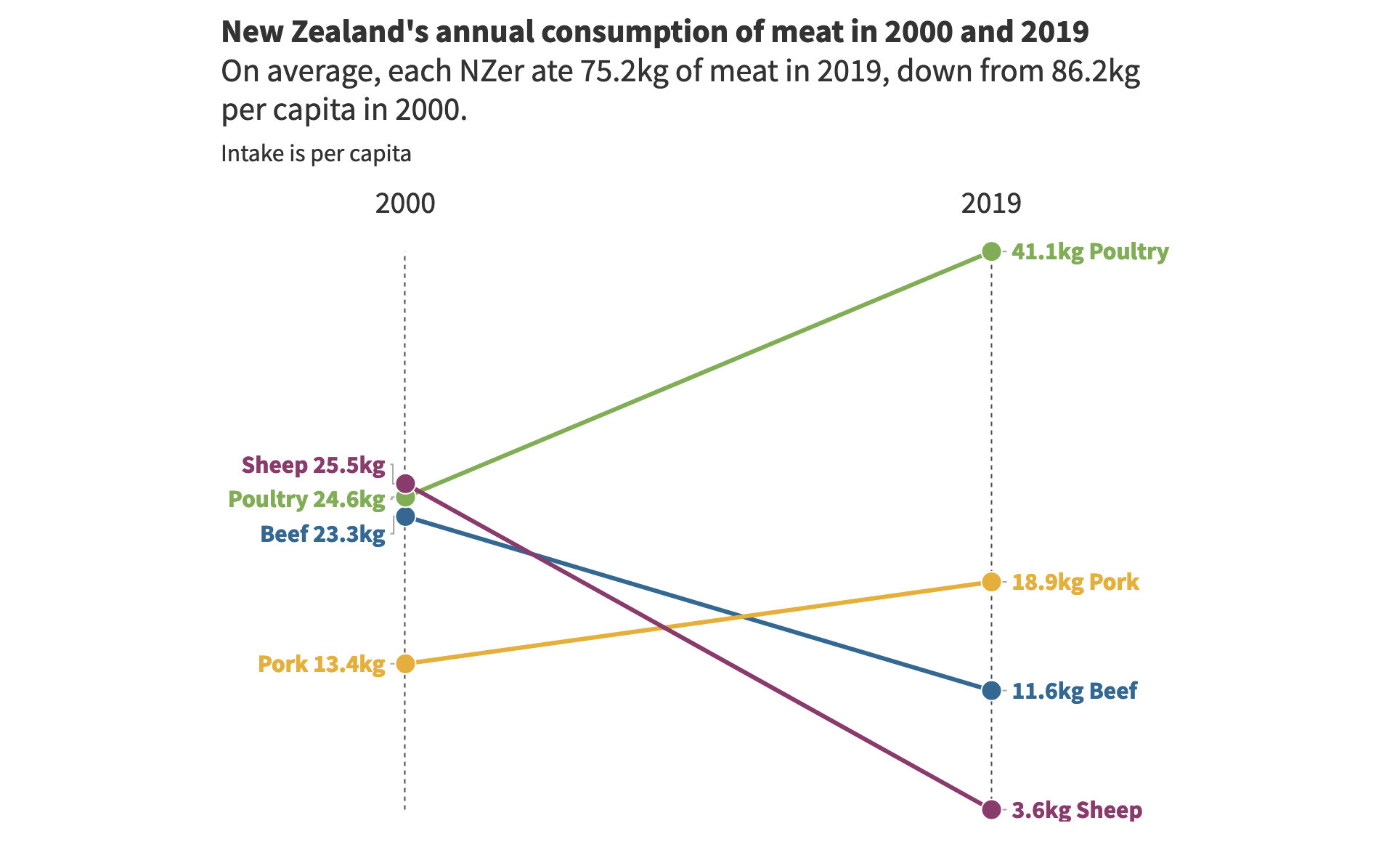

Due to growing evidence and awareness of the climate impact of our diets and specific health risks associated with excessive meat consumption, the average NZ adult decreased their meat consumption from 86.2kg of meat per person a year in 2000, to 75.2 kg of meat per person in 2019. Poultry is the most commonly consumed meat in NZ (41kg per person annually), followed by Pork (19kg), Beef (11.6kg), and Sheep (3.6kg).

When compared with the average consumption of meat globally NZ sits at the higher end of world meat consumption. Average global consumption rose from 29.5kg per person in 2000, to 34kg per person in 2019. (Bogueva et al, 2021)

It would appear the vast majority of NZ adults are meeting their daily requirement for meat or meat substitutes. An online nutrition survey conducted by AgResearch in 2021 showed that 93% of New Zealanders eat meat, although almost half the population reports reducing their meat consumption in response to health, climate, and financial concerns. Despite an abundance of meat alternatives on the market, the online survey showed there is still a “very low” level uptake of meat substitutes by NZ consumers.

The survey also found that taste was the primary determinant when it came to purchasing meat, with the second most common consideration being price. Eight out of 10 NZ adults surveyed said they had never tried a meat substitute product. Nearly half the survey respondents (47%) reported reducing their meat intake over the last year. Lack of affordability and health concerns were the main reasons given.

Tips to support your clients

Here's a valuable tip to enhance your client's nutritional journey:

- First, clarify the concept of a serving size of meat, as clients may inadvertently consume 2-3 servings in a single meal.

- Highlight the importance of opting for leaner cuts of meat and offer guidance on reducing red meat consumption.

- Encourage the integration of at least one meat-free meal each week to diversify protein sources and promote a balanced diet.

MoH: Statement 2 – Choose and/or prepare food and drinks

This statement focuses on making informed choices to improve the nutritional quality of your diet as well as knowing how to best prepare foods and drinks.

This includes choosing and preparing with:

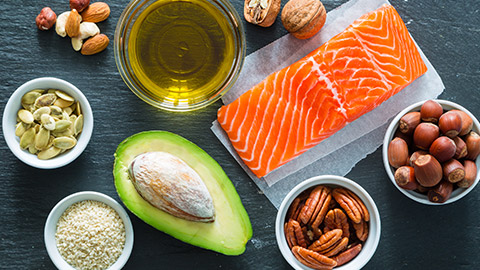

- Unsaturated rather than saturated fats: Opt for sources of healthy fats such as avocados, nuts, and olive oil, while limiting saturated fats found in fatty meats and full-fat dairy.

- Lower sodium: Select options with reduced sodium content to support heart health and manage blood pressure.

- Lower sugar: Prioritise foods and beverages with limited added sugars and aim for natural sources of sweetness from fruits.

- Reduced processed foods: Minimise consumption of highly processed foods that often contain excess salt, sugar, and unhealthy fats.

Choose unsaturated rather than saturated fats

The Ministry of Health recommends replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats due to the significant impact that the types of fats individuals consume can have on their risk of developing cardiovascular disease. Reducing saturated fat intake and partially replacing it with unsaturated fats (in particular polyunsaturated fats), is linked with a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease. The evidence-based research underpinning these Guidelines Statements supports eating patterns that include plant- and marine (fish)-based fats, but that are low in saturated fat. The recommended intake for saturated fat and trans-fats together is no more than 10 percent of total energy.

Unsaturated fats come mainly from plants. They are in foods such as seeds, nuts, avocados, canola and olive oil, and plant-based margarine. Some unsaturated fats come from animals, including oily fish like salmon, tuna, mackerel, and sardines. The following images taken from the MoH eating activity guidelines suggest some ways of reducing the amount of saturated fat you eat and ways of replacing it with unsaturated fats.

Preparation tips

- Choose meat with little visible fat or remove fat before cooking.

- Cook meat in a way that removes rather than adds fat. For example, you could:

- grill it

- roast

- bake it, putting the meat on a rack so fat can drip off during cooking

- boil it and skim off the liquid fat that comes to the surface.

- Leave the skin on when roasting or grilling chicken to help keep in the moisture, then remove the skin and serve the chicken without it.

Try it out

Explore healthier alternatives to saturated fats. By clicking on each saturated fat item, you'll reveal its corresponding unsaturated fat replacement. Discover how you can help your clients make more mindful choices to support their health and well-being.

Instructions:

- Click on each saturated fat item to unveil its unsaturated fat replacement.

- Take a moment to read about the healthier alternatives and consider incorporating them into dietary choices.

- Explore the variety of unsaturated fats that can help make positive changes to nutritional intake.

- Use this information to make informed decisions when helping your client prepare meals and snacks.

- Remember that small changes can have a big impact on overall health. Enjoy exploring the options!

Margarine or other plant-based spreads.

Water, small amount of plant-based oils, eg, canola.

Low- and reduced-fat milks, reduced-fat cheese.

‘Lite’ coconut cream or coconut milk or dilute with water.

Healthier takeaways, e.g., salad-rich kebabs or wraps; vegetable-rich non-fried Asian rice or noodle dishes.

Whole or less processed foods, e.g., vegetables, fruit, unsalted nuts.

The following is a short video that describes the effects of a diet high in saturated fat.

The latest NZ Adult Nutrition Survey reported that the average amount of total fat NZ adults consumed was around 34% of their total energy. While this amount just falls within the recommended range of 20-35%, too much of this was saturated fat (13% compared to the recommended 10%). Most saturated fat consumed by NZ adults was from butter, cheese, and other condiments added to food during or after cooking.

Tips to support your clients

Here are some useful tips to help your client choose and prepare foods of more nutritional quality:

- Equip your clients with an understanding of saturated fat sources in their diet.

- Guide them through practical methods to reduce saturated fat intake (including replacing them with unsaturated fat food items and ways to prepare meats), while boosting their consumption of healthier unsaturated fats.

This guidance empowers them to make informed dietary choices that contribute to their overall well-being.

Lower sodium

Having a diet that is low in salt (sodium) is a key part of a healthy eating pattern that is linked with a lower risk of developing non-communicable diseases. The World Health Organisation strongly recommends consuming less sodium to lower blood pressure and the risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke. New Zealanders consume more sodium than recommended.

Most sodium in the NZ diet comes from salt (sodium chloride) in processed foods while about 10–20 percent comes from discretionary salt. For example:

- salt added during and after cooking).

- Processed foods that are high in sodium include savoury snacks (e.g., crisps).

- processed meat (e.g., sausages, bacon, ham, and luncheon, salted and canned corned beef).

- sauces (e.g., tomato and soy) and fast foods.

- Bread contains moderate amounts of sodium but, because people tend to eat it frequently, it is often a major source of sodium in the NZ diet.

The following video discusses the negative effects of high salt intake.

The less processed the food, the less salt it will generally contain. It is best to choose less processed foods that a low in sodium including fresh or frozen vegetables, fruit, meat, fish, and poultry.

Compare the food labels on packaged products and choose those that fit in the low-salt category. The Stroke Foundation (2011) has recorded the following amounts of sodium.

- Low-salt foods have less than 120 mg of sodium per 100 g.

- Moderate-salt foods have 120–600 mg of sodium per 100 g.

- High-salt foods have more than 600 mg of sodium per 100 g.

Use this information to read and compare food labels.

Tips to support your clients

The following lists some helpful tips to improve your clients’ choices and food preparation:

- Educate your clients on interpreting food labels to compare products and select low-sodium options.

- Familiarise them with the sodium content in everyday foods through label reading.

- For those who add salt to their meals, suggest transitioning to iodised salt and gradually reducing its use.

- Recommend incorporating flavour-enhancing alternatives like herbs, spices, or citrus to reduce reliance on salt.

Lower sugar

Having a diet that is low in added sugar is a key part of a healthy eating pattern that is linked with a lower risk of excess body weight and related non-communicable diseases. Because consuming free sugars is linked with excess body weight and tooth decay, the World Health Organisation strongly recommends that people lower their intake of free sugars to less than 10% of their total energy intake (obesity) and 5% (tooth decay). Adding sugar increases the energy (kilojoules) content of food and drinks but adds no other useful nutrients.

The major sources of sugar in the NZ diet are:

- Soft drinks, fruit juices, and cordial.

- Lollies and sweets like desserts.

- Added sugar (in hot drinks, on cereal etc).

- Baked goods, such as cakes and biscuits.

This short video discusses the effects of a high-sugar diet.

According to Berridge (2017) the average New Zealander consumes around 37 teaspoons of sugar a day! This is around six times the daily recommended consumption rate set by the WHO of 6 teaspoons a day. While some of this is consumed in obvious sources like sugary drinks and added sugar, the sugar comes from virtually everything we eat including bread, cereals, crackers, biscuits, sauces and other snacks. Berridge suggests most NZ adults would have consumed their ideal daily intake of sugar by the end of breakfast.

Tips to support your clients

The following lists some helpful tips to improve your clients’ choices and food preparation:

- Teach your clients in reading food labels effectively.

- Provide a practical understanding of sugar content by using teaspoons of sugar as a comparison (e.g. 4g of sugar = 1 tsp).

- Foster awareness that sugar remains sugar, regardless of its presentation. Whether in fruit juice, honey, or syrup form, it retains its sugar content.

Lower processed food

In a wider context, the term processed food refers to any food that has been:

- milled

- cut

- heated

- cooked

- canned

- frozen

- cured

- dehydrated

- mixed

- packaged.

It relates to any food that has undergone any other process that alters the food from its natural state.

Some of these processes like canning, freezing, and cooking do little to change the “whole” nature of a food, but many of the other processes listed above alter ingredients significantly from their whole food state. These types of food are referred to as “highly” or “ultra” processed.

Highly processed foods often have added fat, sugar and/or salt and contain low levels of naturally occurring dietary fibre, vitamins, minerals, and other phytonutrients. People with the lowest intakes of these foods are consistently the closest to meeting nutrient goals for preventing obesity and non-communicable disease.

Highly processed food is beginning to dominate the food supply of high-income countries like New Zealand. Healthier eating patterns based on regular, freshly prepared meals are being replaced with frequent snacking on energy-dense (high-kilojoule), fatty, sugary or salty ready-to-eat foods. A University of Auckland report from 2019 (The State of the Food Supply), found that 69% of the 13,000+ packaged foods in the survey were categorised as ultra-processed. In many product categories, more than 85% of products were ultra-processed, including snack foods, bread products, meat alternatives, and sauces and dressings (Castles, 2021).

The following short video from the BBC looks at a comparison between a diet high in highly processed food versus one low in highly processed food by having a pair of twins undertake different diets, to see how the different diets affect them over a period of 2 weeks.

While this video referred to British statistics, NZ statistics do not make much better reading. The University of Otago’s Edgar Diabetes and Obesity Research Centre studied more than 800 Dunedin children from birth to 10 years old and found that by 12 months old, 45% of total dietary intake was from ultra-processed food (rising to 51% by age 5). The main foods contributing to these levels were bread, yoghurt, crackers, chips, cereals, sausages, and muesli bars (Fangupo, 2020).

Unfortunately, there is no NZ data reporting how much highly processed food NZ adults eat, but we are likely to be on par with other countries following typical Western diets like the USA and UK which are estimated to consume 60% of total energy from highly processed food and Australia (42%).

Tips to support your clients

The following lists some helpful tips to improve your clients’ choices and food preparation:

- Help clients identify the highly processed foods in their current diets.

- Assist clients by making suggestions to reduce the intake of highly processed foods with simple food exchanges (i.e. replace processed with whole foods).

- Educate clients to be able to read and understand food labels. A starting point may be to remind them of the health star rating system used on packaged food in NZ which can be an indicator of nutritional value.

Try it out

Explore healthier alternatives to processed foods. By clicking on each processed food item, you'll reveal its corresponding replacement. Discover how you can help your client make more mindful choices to support their health and well-being.

Instructions:

- Click on each processed food item to unveil the suggested replacement.

- Take a moment to read about the healthier alternatives and consider incorporating them into dietary choices.

- Explore the variety of replacement food items that can help make positive changes to nutritional intake.

- Use this information to make informed decisions when helping your clients prepare meals and snacks.

- Remember that small changes can have a big impact on overall health. Enjoy exploring the options.

Whole grain cereal like porridge or whole wheat breakfast biscuits

Higher-fibre, whole grain varieties

Low-fat and low-sugar yoghurt mixed with fresh/frozen fruit

Fresh fruit or a small handful of unsalted nuts

Raw vegetable sticks and hummus

A glass of chilled water with fresh mint or lemon

Let’s look at how we can manipulate these guidelines to suit a range of different client goals.