In this section you will learn to:

- Obtain written or verbal delegation for an allied health activity from the Allied Health Professional.

- Obtain information from relevant sources and delegating Allied Health Professional, according to organisational policy and procedures.

- Discuss and confirm with delegating Allied Health Professional minimum health status required by the person for participation in therapy or intervention and work health and safety (WHS) requirements

Supplementary materials relevant to this section:

- Reading A: Making the decision in delegating and identifying tasks

This section of the module describes the role of an allied health professional in delegation of appropriate tasks for implementation by allied health assistants and disability support workers. It provides information about when it is appropriate to delegate tasks, the identification of suitable tasks for allied health assistants and disability support workers, and the importance of establishing strong communication links between team members involved in a client’s support. In addition, this section discusses the concept of accountability that allied health professionals, line managers, disability support workers and allied health assistants hold, and where the accountability sits in relation to delegated and identified (and allocated) tasks. There are a number of pathways to ensure safe and appropriate delegation of an allied health task to an allied health assistant or disability support worker.

As demand for allied health services increases under the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), there is a need for new workforces and service models that make the best use of available skills across the workforce, particularly in rural and regional areas.

You need to understand that allied health encompasses a broad group of health professionals who use scientific principles and evidence-based practice for:

- diagnosis and case formulation

- evaluation and treatment

- support of acute and chronic diseases and conditions

- prevention of decline and disease

- promotion of wellness for optimum health and quality of life

Allied health in disability services focuses on optimising skill, wellbeing and functioning for individuals with a disability, to ensure they live the life they would like to live. A skilled and flexible Allied Health Assistance (AHA) workforce that is able to work with particular allied health disciplines or in multidisciplinary allied healthcare teams will help to alleviate some of the increasing demand pressure on allied health services and allow for the delivery of new and innovative models of care in response to community need.

Effective teamwork

Let’s take a look at what makes working in an allied health care system effective; remember, as an AHA you will be required to question, understand and maybe even reconfirm certain policies and procedures with your direct supervisor an Allied Health Professional (AHP). Characteristics of effective healthcare teams have been identified to include:

- a clear team vision and goals that team members are committed to achieving

- a focus on delivering patient-centred care

- support for innovation and task orientation to provide high-quality and safe patient care

- an identifiable team leader

- clearly defined roles for team members

- a commitment among team members to work collaboratively

- guidelines to support the way the team undertakes its work

- good communication between team members on a regular basis (either face to face or by alternative mediums)

- the ability to monitor and evaluate team performance.

It is important to recognise that differences of opinion are healthy. Encouraging open communication with respect for each other, and developing team members’ skills to constructively resolve differences, are important in strengthening team performance.

Allied health directors/managers also identify the importance of ensuring AHAs are appropriately involved in team meetings, patient handovers, and reviews. This is particularly important for AHAs working in multidisciplinary/interdisciplinary teams, who are often providing care to individual patients receiving care from a number of AHPs. It is particularly important that AHAs understand the overall treatment goals for each individual patient.

Let’s now briefly identify your role as an AHA, remember this might be different and varied across AH centres, therefore make sure you go through the workplace policies and procedures prior to making any decisions and understand your scope of work.

AHA responsibilities

When working under the supervision of an AHP, an AHA needs to ensure that they:

- understand that the AHP is responsible for patient diagnosis and overall care and treatment

- planning, while the AHA is responsible for delivery of elements of the care or treatment plan

- fully understand what is expected of them in relation to tasks being delegated and seek clarification where required

- raise concerns if they feel they do not have the necessary skills to undertake a task being delegated to them

- seek the support of an AHP where there is a concern about patient safety

- actively participate in the clinical supervision process

- regularly participate in appropriate professional development activities.

Now that you may briefly understand your role as AHA, once again reiterating that your role maybe different when it comes to the place you work at, let’s look at the concept of delegation. This is for you to obtain information from your supervisor regarding specific Allied Health activities.

This section defines the concept of delegation. It discusses when it is appropriate to delegate or assign tasks and identifies factors that need to be considered in delegating tasks. It also provides a series of principles that support effective delegation and discusses the level of accountability that AHPs and AHAs hold in relation to delegated tasks.

What is delegation?

In this context, delegation is the process by which an AHP allocates work to an AHA who is deemed competent to undertake that task. The AHA then carries out the responsibility for undertaking that task.

AHPs have responsibility for all diagnoses and clinical decisions regarding patient care, including developing care plans. It is never appropriate to delegate these responsibilities. However, delivery of care plans may involve various members of the team.

There is a distinction between delegation and assignment. Delegation involves the AHA being responsible for undertaking the task while the AHP retains accountability. Assignment involves both the responsibility and accountability for an activity passing from the AHP to the AHA.

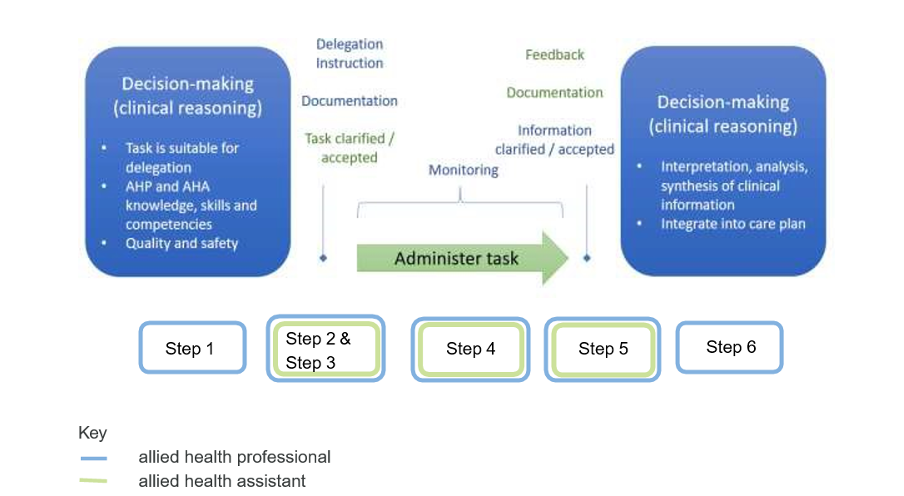

Let’s take a look at the six (6) steps for Allied Health Professionals (AHP) delegating a task. It is quite a process and we have filtered the information; however, there will be readings and links in this section to support your understanding on delegation.

- To determine whether to assign a task, the allied health professional applies clinical reasoning and decision-making techniques. The decision to delegate a task rest with the allied health professional, who will take into account the task, client, stage of the care plan, setting, and team.

- The allied health professional provides a delegation instruction that includes all relevant information, so that the task can be undertaken safely and consistent with the client’s care plan. Delegation of the task is documented.

- The allied health assistant seeks clarification or further information from the allied health professional if required and indicates that the delegated task is accepted. The allied health assistant may decline the task if they do not possess the training and competency to implement the task safely or there are other barriers to implementing the task as requested (e.g., workload/priorities, gender or cultural appropriateness).

- The allied health assistant administers the task. The delegating allied health professional implements the form and frequency of task monitoring that is required to support safety and quality. Task monitoring will take account of the knowledge and skills of the allied health assistant, the needs of the client, the service setting, and the task assigned. The allied health assistant and the allied health professional must have a clear and agreed process for the assistant to escalate issues or to seek support and/or advice during the delegated task.

- Once the task is completed the allied health assistant, provides feedback to the allied health professional, including observations and the outcomes of the task, and documents in the client record.

- The feedback provided by the allied health assistant is considered by the allied health professional to inform their decision-making. Further clarification is sought if required. The allied health professional uses clinical reasoning to integrate findings and outcomes into the client’s care plan.

Tip - Find out more

The Allied Health Assistant Framework, compromises of eight components it basically outlines specific guidelines that provide a clear and consistent direction for health services. This document is mainly for those working with allied health assistants but will also help you get a bigger picture of what is required from you as an AHA, so do have a read through this document.

Delegation requires the AHP to apply their clinical reasoning and professional judgement to determine if the task is to be delegated and to interpret and integrate the outcomes of the delegated task into the care plan. Delegation is initiated by the delegation instruction and includes task monitoring and feedback processes and requires the patient to consent to the task and for the task to be delivered by an allied health assistant.

Read

Reading A: Making the decision in delegating and identifying tasks

Reading A will give you a great insight into the decision-making process of delegating tasks in the Allied Health Sector, it comes from the viewpoint of an AHP however may have some adequate information when it comes to you answering questions on the Assessment Book.

Remember that when a task is delegated, the responsibility for ensuring safe and effective care is shared by the allied health professional, the AHA and the employer. As an AHA, always bear in mind that when you have been delegated with a task that is must include the following information:

Reflect

Remember as an AHA you will be delegated certain tasks and sometimes the AHP might forget certain information, it is your duty to clarify any doubts and make sure that the instruction for delegation should be documented using agreed local processes and standards. For example, notated in the clients’ medical record or as part of a workplace instruction for a protocol driven task.

Once you accept the task and seek clarification of any information that is unclear, you may also raise any concerns about your own level of experience and competence to carry out the activity or request additional support as part of the negotiation process with your AHP.

As an AHA you share the responsibility with your superior who happens to be the AHP, regardless of whether you have the confidence and the competence to perform the task for the specific patient, session and setting. It is your responsibility to identify concerns regarding the workload management and any confidence or gaps in your experience or skill when undertaking these tasks for the planned local context, clarifying instructions and requesting additional information and support.

The table below from the Tasmanian Government (2012), depicts a decision-making process that an AHA can question prior to accepting any task.

| If Yes to all, proceed with the delegation instruction |

Scope of practice

|

If No to any, seek clarification |

|

Individual competence

|

||

|

Risk management

|

||

|

Support

|

||

|

Feedback and documentation

|

||

|

Workload management

|

The outcome of this step is an agreement, negotiated between the allied health professional and the AHA, for how, when and where the task will be implemented.

Tip - Find out more

In this video, we hear stories from staff located in a range of Queensland health services, who share their experiences with developing the scope of practice for allied health assistants. You will see in the video, there is not a ‘one size fits all’ task list that informs what is in or out of the scope of practice for an allied health assistant. It varies depending on the setting, the allied health assistant, the allied health professional, tasks required of the service and the team.

Remember that regardless of what the AHP tells you to do, all tasks need to be aligned with the organisation’s policies and procedures. It is too detailed to have everything explain on this study guide however we have briefly outlined what you need to look into prior to accepting any task:

- Familiarise yourself with policies and procedures: Obtain a copy of the organisation's policy and procedure manual or access it through the organisation's intranet. Take the time to read and understand the policies and procedures relevant to your role as an Allied Health Assistant. Policies and procedures typically cover a wide range of topics, such as patient confidentiality, infection control, documentation, and specific protocols for different tasks.

- Seek guidance from your supervisor or manager: If you have any questions or need clarification about specific policies or procedures, reach out to your supervisor or manager. They are there to provide guidance and support. Schedule a meeting or ask for a brief discussion to address your queries or concerns.

- Attend orientation and training sessions: Organisations often conduct orientation sessions for new employees to provide an overview of the policies and procedures. Take advantage of these sessions to learn about the organisation's expectations, protocols, and any recent updates or changes. Additionally, attend any training sessions or workshops that are provided to enhance your understanding of specific policies or procedures.

- Utilise available resources: Many organisations have resources available to employees to access policies and procedures. These may include online portals, intranet sites, or physical copies of the policy manual. Familiarise yourself with these resources and utilise them as needed to obtain the required information. If you are unsure about the availability of resources, inquire with your supervisor or HR department.

- Maintain open communication: Stay informed about any updates or changes to policies and procedures. Organisations periodically review and revise their policies to ensure they align with current best practices and regulations. Maintain open communication with your supervisor, attend staff meetings, and stay updated on any policy changes through official communication channels like email, newsletters, or bulletin boards.

- Follow reporting channels: If you encounter a situation where a policy or procedure is not clear or seems to be outdated, report it through the appropriate channels. This may involve notifying your supervisor, manager, or the designated person responsible for policy compliance and implementation. Your feedback can contribute to the improvement of policies and procedures within the organisation.

Remember, each organisation may have its own specific processes for accessing and understanding policies and procedures. It is essential to familiarise yourself with the particular procedures and guidelines within your workplace and follow them accordingly.

Tip - Find out more

The allied health assistant orientation workbook provides support to workers commencing in an allied health assistant (AHA) role for the first time. It is designed to complement Hospital and Health Service (HHS) induction and local workplace orientation/ training. The workbook is for use by you and your manager, to ensure that you get the most out of your orientation and make a great start to your new position as an AHA at this facility. Not all components of the workbook may be relevant to you. Your manager will be able to provide guidance on which elements are most applicable to you.

As an AHA, providing feedback before, during, and on completion of delegated therapy is an essential aspect of effective communication and collaboration within a healthcare team. Here is a general process for providing feedback at each stage:

| Stage of feedback | Process |

|---|---|

| Before delegated therapy | 1. Clarify Expectations: Clearly communicate the goals, objectives, and expectations for the delegated therapy to the individual or team responsible for carrying it out. Ensure they have a clear understanding of the desired outcomes and any specific instructions or guidelines. 2. Provide Training and Resources: Offer appropriate training and resources to equip the individual or team with the necessary knowledge and skills to perform the delegated therapy effectively. This may include sharing protocols, demonstrating techniques, or offering educational materials. |

| During delegated therapy | 3. Regular Check-ins: Maintain regular communication and check-ins with the individual or team performing the delegated therapy. This allows for real-time feedback and the opportunity to address any questions, concerns, or challenges that may arise. 4. Observations and Assessments: Observe the delegated therapy sessions whenever possible to assess the quality of care being provided. Make note of strengths and areas for improvement, as well as any deviations from the desired approach or protocol. 5. Ongoing Communication: Provide constructive feedback during the therapy sessions, highlighting what is being done well and offering suggestions for improvement. Encourage open dialogue and ensure that the individual or team feels comfortable seeking clarification or guidance as needed. |

| On completion of the delegated therapy | 6. Evaluation and Reflection: Evaluate the overall performance of the delegated therapy based on the established goals and objectives. Reflect on the outcomes achieved, patient feedback (if available), and any challenges encountered during the process. 7. Feedback Session: Schedule a dedicated feedback session to discuss the outcomes, performance, and areas for improvement with the individual or team involved. Provide specific and actionable feedback, focusing on both positive aspects and areas that require further development. 8. Recognition and Support: Acknowledge and recognize the efforts and achievements of the individual or team. Offer support, additional training, or resources if necessary to help them enhance their skills and knowledge. 9. Documentation: Document the feedback provided, including the strengths identified and areas for improvement. This documentation can serve as a reference for future performance evaluations and as a guide for further professional development. |

Advance care planning is a voluntary and beneficial process, in which individuals can think and plan for their future care; that is, care that is required during periods where they cannot make contemporaneous decisions for themselves. It can bring to light an individual’s values, beliefs and preferences, including:

- what characterises acceptable or non-acceptable health outcomes for each person

- who should be involved in making decisions about an individual’s care

- what are the types of medical responses they would like for different stages of wellness or illness

- what are the individual’s preferred care, or carer arrangements.

Advance care planning is the context in which future care is discussed. Advance care planning can occur at any time, including when an individual is in full health. It may be an iterative conversation, where an individual’s values, beliefs and preferences change and evolve over time. It might also coincide with a conversation about setting goals of care. Conversations are valuable in their own right; however, the completion of an advance care planning document may provide important information to inform future care decisions.

Advance care planning is therefore the embodiment of person-centred care and is based on fundamental principles of self-determination, dignity and the avoidance of suffering. In addition to better outcomes for the individual, advance care planning supports health practitioners and the wider health system to provide person-centred care.

This Framework is designed to support increased awareness and uptake of advance care planning which would see more people in Australia preparing, using and maintaining advance care planning documents.

To ensure that ethical considerations and best practice principles that inform advance care planning legislation, policy and implementation are comprehensively applied, it is helpful to consider the typical stages an individual may go through during their advance care planning journey (noting that these may be iterated across an individual’s lifetime). Subsequent sections on ethical considerations and best-practice principles are divided according to these stages. The figure below summarises the three stages of advance care planning used in the Framework.

- Having the advance care planning conversation and considering documenting an individual's values and preferences for future care in some way.

- Making an advance care planning document

- If the individual has decision-making capacity, an Advance Care Directive is preferable.

- If the individual does not have decision- making capacity, an Advance Care Plan can be made

- These documents should be stored somewhere where they can be easily identified and accessed, such as My Health Record.

- Accessing and enacting an advance care planning document to inform care decisions made by substitute decision-makers and health practitioners

Tip - Find out more

This topic is once again very informative therefore you are required to have a read through this document to understand how to conduct appropriate advanced care planning conversations with patients under your care, what are the requirement and processes towards this and the legal virtues that follow. Read this to find out more.

Following standards, as highlighted by Department of Health, 2021 in Victoria Infection control, standard and transmission-based precautions is a must in infection control. Your effective work role in Allied Health is to follow professional protocol to keep yourself and others safe.

You have a responsibility to yourself to ensure you are doing the best possible job in the Allied Health Field. Knowing your industry and linking in with peak bodies, such as Allied Health Professions Australia will give you a clear picture of the Allied Health profession as a whole and where you might fit into the picture.

Keeping in check your mental and emotional, as well as physical health means that you are bringing your best self to your work role. There are a range of resources available to you on the Allied Health Professions Australia website.

You can use a risk management approach such as that set out in the Australian/New Zealand Standard Risk Management – Principles and guidelines, or your organisation may use a general risk analysis matrix, such as the matrix below:

| Likelihood | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rare | Unlikely | Possible | Likely | Almost certain | ||

| Consequences | Major | Moderate | High | High | Critical | Critical |

| Significant | Moderate | Moderate | High | High | Critical | |

| Moderate | Low | Moderate | Moderate | High | High | |

| Minor | Very low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | |

| Insignificant | Very low | Very low | Low | Moderate | Moderate | |

Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infection in Health Care (NHMRC 2010) basic principles of risk management are to:

- The health system - the risk may be outside the control of an organisation.

- The organisation - the risk may be corporate or clinical in nature.

- The team who are delivering the care - the risk may come from the pattern of

- work or team dynamics.

- The individual - the risk may be skills, knowledge or situationally based.

To minimise risks, you will need to identify:

- Who is at risk?

- What is involved?

- Why can it happen?

- How likely is it?

- What are the consequences?

- What can be done?

- Is the solution applied to the situation/risk identified?

Risk management

As a healthcare administrator, the possibility of incurring misfortune and loss is present. Risk management is a proactive approach, and its aim is to prevent or minimise harm. The implementation of a formal risk management process will identify potential problems and the potential for harm to patients. Once the risks are identified, actions are then planned to reduce the likelihood of the problem arising or to limit the harm caused.

The four key stages

| Steps taken | Explanation |

|---|---|

| 1. Risk identification | This stage involves:

|

| 2. Risk analysis |

This stage estimates the likely consequence that the identified risks might have on the patient. You may use the following key questions to analyse the risks involved:

Type I error - these occur due to an act of omission, e.g., failure to comply with current professionally accepted practice. The basic cause of a Type I error is lack of knowledge, and it is typically common in health care institutions where there is inadequate provision of education, training, and supervision. Type II error - these occur due to an act of commission, e.g., an act should not have been committed. These are due to lack of commitment or consideration for others. Type III error - these mainly occur due to a failure to understand the true nature of the problem. Real solutions are adopted to deal with the wrong problems, rather than incorrect solutions to real problems.

This information is quantitative and can be obtained by ongoing surveillance data (if available) or by performing a point prevalence study. Frequency can be measured as the percentage or rate of persons who developed infection following either a clinical procedure or exposure to a pathogen.

The cost of prevention of infections is important because it helps IPC practitioners to target resources where they will deliver the greatest advantage in terms of preventing harm to patients. |

| 3. Risk control |

|

| 4. Risk monitoring |

|

Recording and documenting risks and incidents

At first, your supervisor or other HCWs will ask for a clear description of the incident with as much detail as possible. This will help them assess whether or not the incident is notifiable and the need for a follow-up investigation. The following information has been recommended by Safe Work Australia (2015):

| What happened? |

|

|---|---|

| When did it happen? | Date and time |

| Where did it happen? |

|

| What happened? | Detailed description of the notifiable incident |

| Who did it happen to? |

|

| How and where are they being treated (if applicable)? |

|

| Who is the person conducting the business or undertaking (there may be more than one)? |

|

| What has/is being done? | Action taken or intended to be taken to prevent recurrence (if any). |

| Who is to be notified? |

|

Now that you are aware of all the cleaning protocols that a HCW must adhere to, let’s take a look at the prevention of microbial contamination by removal, exclusion, or destruction of microorganisms, better known as asepsis.

Notice that the standard precautions are once again the same:

- Hand hygiene

- Aseptic technique

- Use of personal protective equipment (PPE)

- Respiratory hygiene and cough etiquette

- Safe use of sharps

- Environmental cleaning

- Reprocessing of medical equipment

- Appropriate handling of linen and waste management.

Aseptic in different settings

| Settings | Examples |

|---|---|

| Clinic |

|

| Pharmacy |

|

| Laboratory |

|

Essential principles

As a health administrator, it might not come off as a mandatory requirement to understand the following principles; however, it’s best to know what needs to be done prior to a procedure and the aseptic techniques alongside these. These principles are:

Sequencing

Sequencing involves a series of actions that ensure each procedure is performed in a safe and appropriate order. Sequencing includes assessing for risks to patient safety and the HCW and identifying strategies to mitigate these risks prior to starting the procedure.

Environmental control

There are many factors in the clinical environment which can increase the risk of infection and patient harm during a procedure. Therefore, all HCWs need to make sure the area/environment they are working in, is clean and free of any hazards, risks, and all the equipment are damage and contaminate free.

Hand hygiene

There are critical moments before, during and after an invasive procedure or a procedure requiring aseptic technique when hand hygiene should be performed. This process helps remove transient micro-organisms from the hands.

Maintenance of aseptic fields

The HCW should ensure that the aseptic field, the key parts, and key sites are always protected.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

PPE is important for protecting both the patient and HCW during aseptic procedures.

The table below gives you some examples to consider at each principle stage of asepsis:

| Essential Principles | Factors to be considered |

|---|---|

| 1. Sequencing | Perform a risk assessment:

|

| 2. Environmental control |

|

| 3. Hand hygiene |

|

| 4. Maintenance of aseptic fields |

|

| 5. Personal protective equipment (PPE) |

|

Continuing education and development are important for allied health assistants to maintain and enhance their skills and knowledge. It is a shared responsibility between the individual and their employer, aimed at optimising performance and enhancing patient care. Continuing education and development are linked to supervision.

Performance and development planning

The performance and development planning process established the AHA’s development goals and outlines the development activities required to meet those goals in a learning (i.e. skills and development plan).

Decisions about the most appropriate option for development will be made at a local level where resources should be allocated to support these activities. This includes:

- Allocating time to attend training through scheduled/timetabled events, efficient use of down time or prioritising as part of workload allocation

- Access to training resources including workshop attendance, courses (including formal qualifications), online learning modules, reading and/or viewing materials and

- An audit process to monitor compliance and satisfaction

Continuing education and development activities

Many AH services have invested in the provision of continuing education and development for their AHAs including establishing regular in-services, AHA networks and forums and funding for conference leave. Availability of development opportunities may assist with staff retention.

Continuing education and development opportunities may include:

- Targeted on-the-job training with the specific purpose of developing/enhancing skills

- Enrolment in additional units of competency from the Certificate IV Allied Health Assistance or short courses

- Attendance at webinar, training, conference, forum, or workshop events

- Review of supervision arrangements to include collaborative supervisors, buddy relationships, work shadowing or rotational placement opportunities

- Participation in case discussions, online discussions forums, in-services, or student tutorials

- Contributing to workplace evaluations or newsletters

- Completing contexualised learning modules

In addition, AHAs may participate in other learning support and development activities including mentoring, journal club or peer review.

With the advancement in technologies, there are now more opportunities than ever for helping professionals to develop and extend their knowledge and skills in a convenient and efficient way. However, we must be cautious about how we source information and critically consider if the information is credible, relevant and of good quality for informing your practice. Vast majority of websites and web-based media, including blogs, Wikipedia, and TED Talks, media articles and interview, and non-academic books and journals are non-professional and cannot be relied on for PD (even when they are written or presented by professionals, researchers, scientist, or academics).

So, how can you identify professional literature? Professional literature meets a number of criteria, including that it is:

- Relevant to your field. For helping professionals, this usually means allied health-focussed sources. However, depending on the context of role and clientele, this may also include literature from social work, allied health therapy, and the behavioural and social sciences, or intersect with areas such as health, education, law, and so on.

- Produced by authoritative authors. The people writing and reviewing the material have relevant, high-level qualifications and/or experience that make them authoritative in the area in which they are writing. For example, the author of a Allied Health text should have many years of experience in the community, as well as relevant qualifications.

- Subject to criticism and peer review. The peer review process means that multiple people with relevant expertise, and who are independent from the authors of the work, have critically reviewed it. It is not a perfect process – some articles have passed peer review despite being inaccurate – but it is a level of protection beyond that which non-peer re-viewed sources have. Some sources that would often be assumed to be professional, such as textbooks and other books written for AHAs, are not regularly subjected to peer review. If an article is not peer-reviewed, subject it to additional critical scrutiny. Even when a comprehensive peer review process is in place, however, you have a responsibility to critically evaluate the material.

Note: Checking whether the source you are reading has been peer reviewed is not an overly complicated task. You can usually find this out from the publication information in the front of the printed journal or from the homepage of an electronic journal (Hint: look for links such as ‘about this journal’ or ‘notes for authors’). You should find information that tells you if the articles published in this journal are peer-reviewed. For example, search for “Journal of Allied Health Assistance” online, and on its homepage, click on the link to ‘Guide of Authors’, you will see relevant information under the subheading of ‘peer review’.

Essentially, critically evaluating piece of information means not merely believing or accepting everything that you read, but analysing and evaluating the ideas or arguments presented – this does not necessarily mean finding fault in the information. In the process of critical evaluation, you will ask a number of questions about the information (adapted from Meriam Library, 2010):

| Evaluation Criteria | |

|---|---|

|

Currency The timeliness of the information. |

|

|

Relevance The importance of the information for your needs. |

|

|

Authority The source of the information. |

|

|

Accuracy The reliability, truthfulness and correctness of the content. |

|

|

Purpose The reason the information exists. |

|

The five aspects discussed above formed the acronym CRAAP (Blakeslee, 2004), which is an evaluation tool designed to help make critical evaluation more friendly. You can use this as a prompt– by asking “Is this CRAAP?” – to remind yourself about the important aspects and questions you have to consider when evaluating information.

Generally speaking, a piece of good quality information is one that is more recently dated, contains updated information, has been peer-reviewed and uses a comprehensive range of scholarly and peer reviewed references in development, written by qualified authors in a non-bias way, and demonstrates sufficient evidence to support the claims being made.

Ideally, you should aim to look at a number of resources, by different authors, relevant to the area you are researching about, in order to source different points of view and help you pick up any potential bias or issues. It is also beneficial to bring the information to a discussion with experienced and knowledgeable colleagues or supervisor to determine how relevant or applicable the information is to your practice.

This section of the module provided you with an understanding of how tasks are delegated from your supervisor and what you are required to do before accepting any task.

Remember, the process of obtaining delegation may vary depending on local regulations and workplace policies. It is crucial to follow the guidelines and procedures established within your healthcare setting and consult with your supervisor or manager if you have any uncertainties. Subsequently, you need to make sure that any tasks that you have been delegated with follows the organisation policies and procedures.

Allied Health Professions Australia. (2023). Allied Health and mental health. https://ahpa.com.au/key-areas/mental-health/

Allied Health Professions Australia. (2023). Allied Health Professions. https://ahpa.com.au/allied-health-professions/

Australian Centre for Business Growth. (2023). [Photo of woman and man in business clothes discussing paperwork]. https://centreforbusinessgrowth.com/news-and-events/learn-the-power-of-delegation/

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2019). Examples of IPC risk considerations and risk assessment questions. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-08/guidance_-_covid-19_infection_prevention_and_control_risk_management_002_0.pdf

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2022). The NSQHS Standards. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs-standards

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2022). Shared decision making. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/partnering-consumers/shared-decision-making

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2022). Informed consent. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/partnering-consumers/informed-consent

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2022). Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infection in Healthcare. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/australian-guidelines-prevention-and-control-infection-healthcare

Blakeslee, S. (2004). The CRAAP test. LOEX Quarterly, 31(3). Retrieved from https://commons.emich.edu/loexquarterly/vol31/iss3/4

Meriam Library. (2010). Evaluating information applying the CRAAP test. Retrieved from https://library.csuchico.edu/sites/default/files/craap-test.pdf

Queensland Health. (2022). Allied health assistance framework. https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/147500/AHAFramework.pdf