Earlier we introduced some tools you can use to identify plants, we talked about how to write plant names, and how to assess the health of plants. In this topic we’ll build on this knowledge. We will:

- step back and consider what plants actually need for healthy growth

- introduce a range of plant features that we can use to help us choose plants that complement each other.

By the end of this topic you’ll be able to:

- Write scientific plant names for plants that have a variety or cultivar.

- List the five things that all plants need to grow.

- Match terms about plant characteristics with their meaning.

- Identify different planting colour schemes.

For this topic, we'll start with an Activity that will help to measure your knowledge of plants before we get too into the topic of planting design.

Activity

Off the top of my head…

Using the table in this spreadsheet, make a list of all of the plants you can think of that grow in your region. Fill in as much information as you can from memory, but don’t look anything up.

If you don’t know what the terms at the top of the table mean, just leave those columns blank.

If you don’t know many plants, that’s fine. This topic will help build your knowledge.

If you know lots, stop when you run out of enthusiasm for the task. However, the more you do, the more helpful this list will be.

You’ll get to revise it later.

Post in this forum and let your classmates know how many plants you know – that is how many you listed and were able to describe most of the features for. If you know more about a particular type of plant than others, such as roses, or trees, let them know.

Earlier in this programme we learned about plant names. We learned that each plant species has one official scientific name but may have many common names.

The scientific name is made up of two main parts, the genus and the species, such as Daphne odora.

In this example, the name Daphne is the genus and the name odora is what is called the specific epithet. Together, these two names make up the plant species name (or scientific name).

Classifications below species

We can refer to a particular species by using its binomial (two-part) name, such as, Metrosideros excelsa, (pōhutukawa) but did you know that there can be variation within a species?

Variation may come in the form of different coloured flowers, different shaped leaves, or their ability to grow in different regions to the main species, to name a few.

There are a number of different variations, which are classified based on how they come about. The most common ones are:

- Variety: In botany (the study of plants), the term variety is used to classify a group of plants within a species that differs from the typical form of that species in one or more structural characteristics.

- Cultivar: A cultivar is a ‘cultivated variety’ in other words one that “people have selected for desired traits and when propagated retain[s] those traits” (Wikipedia contributors, 2023).

Cultivars may relate to a species or genus. For instance, there are 39 recorded cultivars, of the pōhutukawa (Metrosideros excelsa) species, including:

- Metrosideros excelsa ‘Aurea’ – greenish-yellow flowers

- Metrosideros excelsa ‘Moon Maiden’ – sulphur yellow flowers

- Metrosideros excelsa ‘Pink Lady’ – melon-pink flowers.

In some cases, the parent plants that the cultivar has been bred from are unknown and in these cases, the cultivar name excludes the specific epithet. This is common with rose cultivars that have been bred for many generations, for instance Rosa 'Munstead Wood’ (English rose ‘Munstead Wood’).

Writing plant names

As a qualified landscaper, which you will be at the end of this programme, you’ll be expected to write plant names according to botanical naming conventions.

There are two ways of writing plant names:

- on a computer

- by hand.

Let’s take a look at how to do both, for species, varieties, cultivars, and hybrids.

| Computer | By hand | |

|---|---|---|

| Species |

Dacrycarpus dacrydioides |

Dacrycarpus dacrydioides |

| Variety |

Phormium tenax var. rubrum |

Phormium tenax var. rubrum |

| Cultivar where the species is known |

|

|

| Cultivar where only the genus is known |

|

|

Synonyms: Alternative scientific names

Synonyms are other scientific names that the plant has been known by in the past. For instance, the tī kōuka (cabbage tree, palm lily) has the scientific name Cordyline australis but has the following synonyms:

- Dracaena australis

- Dracaenopsis australis

It is important to know about synonyms because in some cases the synonym is used more commonly than the verified scientific name.

For instance, Leptinella dioica is a small groundcover native to Aotearoa. It is cultivated for use on natural bowling greens. It was formerly classified as Cotula dioica but has since been reclassified as Leptinella dioica, however, its old name has ‘stuck’ within the sports turf sector. If you needed to write about this plant, you could write Leptinella dioica (syn. Cotula dioica).

Shorthand for plant names

While you should need to use these abbreviations, it is good to know what they mean as you’ll come across them from time to time.

When a plant name has been written in full, it can be shortened for future uses on the same page by using the first letter of the genus and the specific epithet together. For example:

- First use: Sophora microphylla

- Second and subsequent uses: S. microphylla

Additionally, the following abbreviations are often used:

- sp. – means one unknown or unspecified species

- spp. – means more than one species.

Now let’s move on to learn a little more about what plants need to survive.

There are five main things that all plants need to grow:

- light

- air

- water

- nutrients

- something to grow in.

Light

Plants make their own food using a process called photosynthesis and one of the main things needed for photosynthesis is light. For most plants, their light comes from the sun.

Air

Carbon dioxide from the air is another thing plants need for photosynthesis. Cellular respiration – the process of converting stored energy (food) into growth energy – needs oxygen, which it draws in from the air.

Water

Water is needed for a number of different processes:

- It is used in photosynthesis.

- It dissolves nutrients in the soil and draws these into the plant through its roots.

- The pressure of the water in the plant causes it to stay firm and upright. You probably already know this – when a plant doesn’t have enough water it becomes soft and floppy.

- Water evaporating from the leaves creates suction that pulls more water from the roots up to other parts of the plant.

Nutrients

Mineral nutrients are elements that plants need to survive. Different plant processes need different nutrients, for example:

- Nitrogen (chemical symbol: N) is important for the development of branches, stems and leaves.

- Phosphorus (chemical symbol: P) is important for root growth and fruit formation and growth.

Something to grow in

The object that a plant grows in is called the growing medium. In most cases this is soil, but it could also be aged compost or potting mix. The main purposes of a growing medium are to hold the plant in place, and to allow water with dissolved nutrients to enter the plant’s roots.

The most common growing medium is soil. In Aotearoa, we are fortunate to have a lot of soil. But not all soils are the same.

Soil is made up of four key ingredients:

- mineral particles – sand, silt, and clay

- water – sits in some of the pore spaces (gaps) in the soil

- air and other gasses – these fill up pore spaces that aren’t filled with water

- organic matter – living and dead plants, animals (such as worms), fungi, bacteria, and viruses.

In most cases, ideal plant growth occurs when the soil is made up as follows:

The proportions of water, air, and other gasses change often, due to rainfall, irrigation and the drying effects of the sun and the wind.

Water and air fill the pore spaces between mineral particles and organic matter.

During heavy rain or watering, water will push the air out of the pore spaces, and they will become completely filled with water.

After the rain or watering stops, the water in the pores will drain deeper into the soil, and air will be pulled back into the pores. Unless the soil becomes extremely dry, which can happen by the end of a hot summer, it will usually still hold some soil water in the pores.

Adding mulch to our garden beds is a good way of making sure there is enough organic matter. This in turn releases nutrients into the soil as it decomposes.

The information above covers the key things plants need to grow, in a general sense. But in reality, different plants have specific growth requirements. We refer to plants having:

- preferences

- tolerances.

If a plant is said to prefer full sun then full sun is its ideal level of light for healthy growth. If it is said to tolerate wind, then it will grow well in windy conditions but may do better if it was sheltered from the wind.

For each plant we consider specifying in our garden design, we need to look up what it likes and what it will tolerate. The main things we want find are:

- Light: Does it tolerate or prefer full sun, partial shade, full shade?

- Soil drainage: Does it like to have “dry feel” (well-drained soil) or does it prefer moist or moisture-retentive soils?

- Frost: Is it frost tender or frost hardy? Frost tender means it does not tolerate frost while frost hardy – or simply “hardy” – means it does.

- Wind: Does it tolerate exposed (windy) locations, or does it need to be sheltered from the wind?

- Coastal tolerance: For sites near the sea, how well does the plant species tolerate salt spray?

When we know the preferences and tolerances of different plants we can choose the best plants for the garden we’re designing.

Information about plant-specific growth requirements can be found:

- in plant encyclopedias, or encyclopedias more generally, such as Wikipedia

- in online plant databases, for example New Zealand Plant Conservation Network (NZPCN), Auckland Botanic Gardens, or Royal Horticultural Society (additionally, Shoot is very good, but expensive)

- on supplier websites, for instance Southern Woods, Leafland, or The Plant Company

- on the tags found on the plants in a nursery.

Activity

Filling your basket of knowledge

Use a selection of books and online resources to update the plant list that you created at the beginning of this topic, by:

- filling in any blank cells

- making corrections to any information that you’ve since realised is incorrect

- Unhide the “Growth requirements” column and fill this in too. To unhide the column:

- Click at the top of column H (right at the top where it says “H”)

- Hold down the Shift key and click right at the top of column J

Right-click and choose “Unhide” or “Unhide columns.”

Plant features is a term that means the things we can observe about a plant, such as its size, the colour of its leaves, and whether it loses its leaves in the winter. For garden design, the plant features we are most interested in are:

- evergreen or deciduous

- category

- size

- form

- texture

- colour.

Evergreen or deciduous

Plants that lose their leaves and become dormant over winter are said to be deciduous. Plants that keep their leaves year-round are said to be evergreen. A small number of plants are considered semi-deciduous, which means they lose their leaves for a very short period.

When choosing plants for a garden, deciding whether to use evergreen or deciduous plants is a key feature to consider.

Deciduous trees and shrubs can be used effectively where you want to allow winter sunlight to reach certain areas of the garden or house. The disadvantage is that you may need to collect and get rid of (compost) the leaves they drop in winter to prevent them from becoming slippery and dangerous.

Branch patterns of deciduous trees and shrubs provide interest to the garden in winter.

These pleached, European hornbeam trees (Carpinus betulus) offer a visually interesting, structural form even when dormant through the winter. (Image from the Plant Store: https://www.theplantstore.co.nz/pleached-hornbeam-ligularia-buxus/)

Category

By category, we mean:

- tree

- shrub

- perennial

- groundcover, or

- climber.

Annuals – plants that only live for one year or less – are usually left out of garden design plans unless they are a particular feature of the garden. Instead, we focus on perennial plants, as they create the structure of the garden for years to come.

Trees

Trees are typically taller than shrubs, with a single main trunk that grows upwards to form a canopy. There are of course exceptions to this – think of pohutukawa (Metrosideros excelsa) trees that often have multiple trunks – but it's a good basic description.

Trees are used to create the ceiling of garden rooms and create shade.

Shrubs

Shrubs, on the other hand, usually have multiple stems and branches that grow outwards to form a rounded shape.

Shrubs are the most common plants used to create the walls of a garden room.

Perennials

A perennial is any plant that lives for more than two years. Technically speaking, trees and shrubs are considered woody perennials.

Other plants that live for more than two years but which die back to ground level over winter, are known as herbaceous perennials. In general conversation, when we talk about a perennial, we are talking about herbaceous perennials.

We use perennials (both woody and herbaceous) to create three-dimensional forms in the garden and in doing so we define the open centres of our garden rooms based on the negative space left over.

Some examples of (herbaceous) perennials found in Aotearoa are:

- Glen Murray tussock, or trip me up (Carex flagellifera)

- Day lily ‘Cade Stewart’ (Hemerocallis 'Cade Stewart')

- Geranium ‘Rozanne’

- Rengarenga lily (Arthropodium bifurcatum, often sold as either A. cirratum ‘White Knight’ or A. cirratum Matapouri Bay.’

A collection of purple and pink-flowered perennials, including lavender (Lavendula sp.) and sage (Salvia sp.), and low shrubs beneath three standard bay trees (Laurus nobilis).

Groundcovers

Groundcovers are perennials, which spread sideways, rather than up, as they grow. They are a good way of covering bare garden beds. In some cases, groundcovers can be used instead of grass. Groundcovers aren’t necessarily low-growing, but they do form a dense block of planting.

“Ground cover plants are often chosen for aesthetic considerations, such as to introduce new colours or textures into a landscape. Or they can be chosen for practical purposes to cover ground where turf grass does not thrive or is not practical. For example, areas of a yard that are deeply shaded might be a good spot for an alternative shade-tolerant ground cover plant, such as ajuga or pachysandra. Steep slopes that are difficult to mow can also be a good area to plant a ground cover. In arid climates where the high-water demands of grass are problematic, an alternative ground cover can replace grass entirely.” (Beaulieu, no date)

Some examples of groundcovers available in Aotearoa include:

- Cushion plant, or Canberra grass (Scleranthus biflorus)

- Pratia, or panakenake (Lobelia angulata, often sold as Pratia angulata)

- Sedum (Sedum spectabile)

- Ajuga common bugle, or carpet bugle (Ajuga reptans)

When densely planted, Scleranthus biflorus (cushion plant) forms an intriguing, mounded volume.

Climbers

Vines that climb up support structures are called climbers. In some cases, plants we often see growing across the ground can be climbers too if provided adequate support structures, such as pumpkins. More often though, we’re referring to perennial climbers.

Climbers can be used where there is not enough space for a hedge, but where planting is needed to form the walls of a garden room. Growing climbers up a solid fence achieves this goal. Additionally, climbers can be used to form the ceiling of a garden room, if grown up a pergola.

Examples of climbers native to Aotearoa are:

- Akapukaea, or three kings vine (Tecomanthe speciosa)

- Akakura, climbing rata (Metrosideros carminea)

- Puawhananga (Clematis paniculata)

- Native jasmine (Parsonsia heterophylla)

The climbing roses (Rosa ‘Chaplin’s Pink’) fill in the gaps in the pergola, creating the ceiling over the walkway.

Size: height and spread

Spread is the term used to describe how wide a plant gets. The height and spread of a plant are key features as larger plants will have a more dominating presence than smaller ones.

As previously mentioned, it is best to draw plants at their 10 year size, or 80% of full size.

When writing plant size measurements, these are commonly written in metres with the height listed first and the spread listed second. For plants where either measurement is less than a metre, use decimals for both measurements. For example:

- 10x3m means a height of 10m and a spread of 3m, like the nikau palm (Rhopalostylis sapida)

- 0.8x2.0m for a plant that grows up to 80cm tall and has a spread of 2m, like the Japanese quince (Chaenomeles japonica).

Form

A plant’s form (also known as habit, or growth habit) refers to the overall shape or silhouette it creates when growing in its natural environment, without intervention.

However, as with the design element of form, plant forms are three dimensional and generally symmetrical. In other words, the silhouette a plant forms from one angle, is very similar as it looks from another angle.

Common tree forms

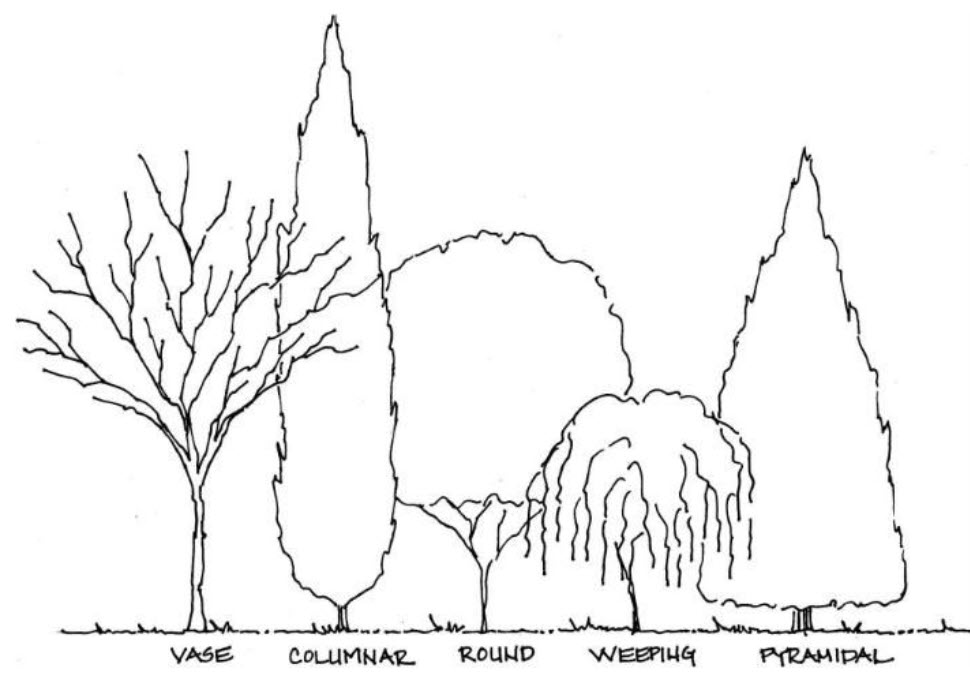

Five of the most common tree forms. Drawing by Gail Hansen (Hansen and Alvarez, no date).

- Vase: These trees have a broad, spreading canopy with an open centre, giving them a vase-like appearance. Examples of vase-shaped trees include crabapples, like the Adirondack crabapple (Malus ‘Adirondack’).

- Columnar: These plants have a narrow, upright growth habit and tend to be tall and narrow, with branches that are closely spaced together. An example of a columnar tree is the Italian cypress (Cupressus sempervirens).

- Round: These plants have a rounded or oval shape, with a broad crown and branches that extend outward from the trunk. Examples of rounded trees include oak trees (Quercus spp.) and most varieties of maple trees (Acer spp.).

- Weeping: These plants have drooping branches that give them a "weeping" appearance. Examples of weeping trees include the weeping willow (Salix babylonica), weeping cherry (Prunus pendula) and silver birch (Betula pendula).

- Pyramidal (also called conical): These plants have a triangular shape, with a single central leader and branches that gradually get shorter as they go up the trunk. Most pine trees have a conical form.

- Spreading: These plants have a wide, spreading growth habit and tend to be shorter and wider than other forms. Examples of spreading trees include some varieties of magnolia (Magnolia spp.).

- Multi-stemmed: These trees have multiple trunks or stems that grow from the same root system, giving them a bushy appearance. An example of a multi-stemmed tree is the pohutukawa (Metrosideros excelsa).

Common shrub, perennial, and groundcover forms

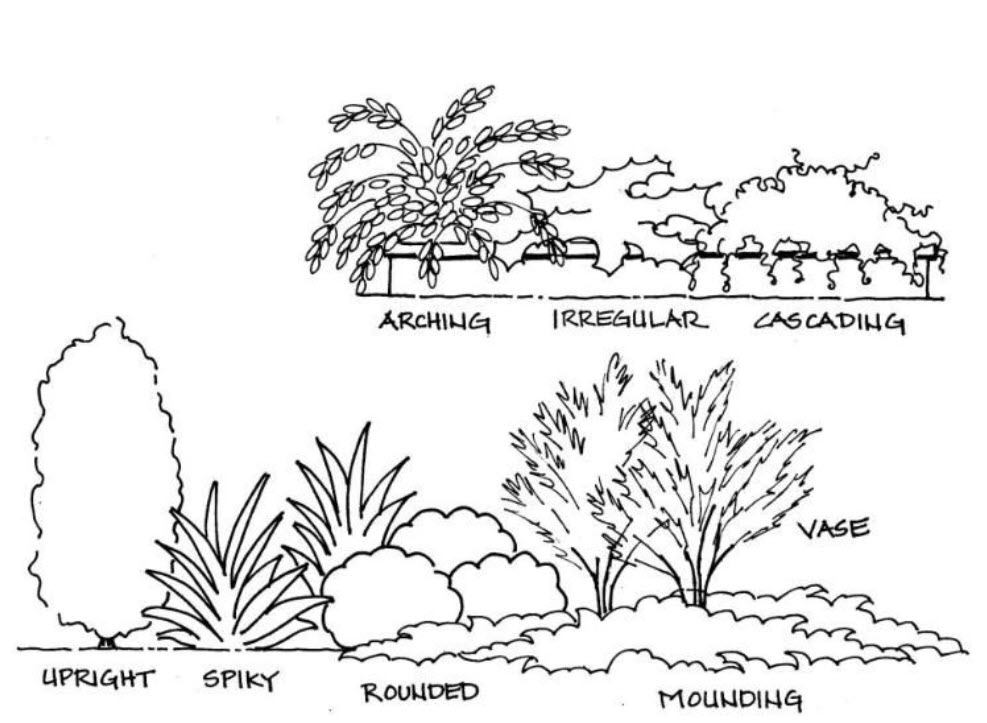

Common shrub and perennial forms. Drawing by Gail Hansen (Hansen and Alvarez, no date).

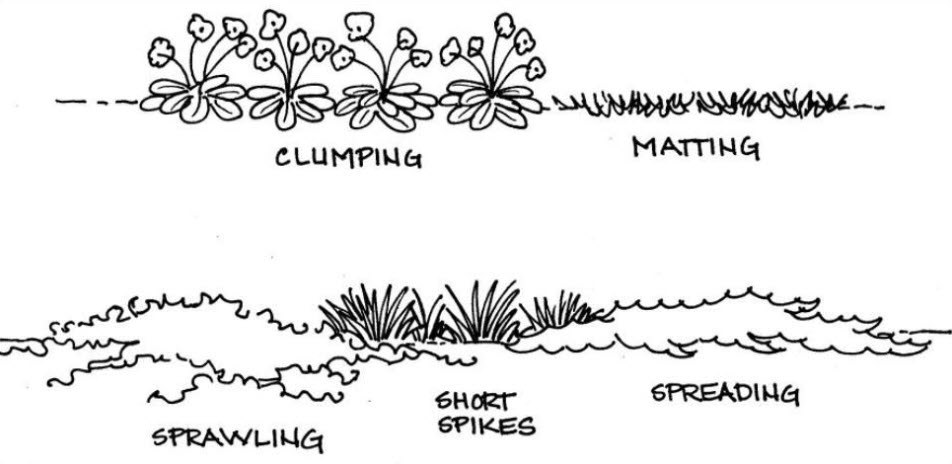

Common groundcover forms. Drawing by Gail Hansen (Hansen and Alvarez, no date).

For simplicity, we can group shrub, perennial, and groundcover forms into three main form types:

- Upright (sometimes called erect, vertical, or clumping): These plants have a vertical growth habit. Rudbeckia (Rudbeckia spp.) is an example of upright annuals. An example of an upright groundcover is the bush lily (Clivia miniata). Upright includes:

- the upright, spikey, vase, clumping, and short spike forms shown in the drawings above.

- Round (sometimes called mounded): These annuals have a mounded or rounded growth habit, with branches that extend out in all directions from the centre of the plant. Hostas (Hosta spp.) are an example of perennials that have a round form. Round includes:

- the rounded and arching forms shown in the drawing above.

- Horizontal (sometimes called creeping or spreading): These plants have a low growth habit that is wider that it is tall. Creeping thyme (Thymus serpyllum) is an example of a horizontal groundcover. Horizontal includes:

- the irregular, cascading, mounding, matting, sprawling, and spreading forms in the drawings above.

Climbers or vines are generally said to have a climbing habit, or form. An example is kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa).

Plant form as a design tool

Plants create three-dimensional forms that can create the walls of a garden room, screening, or separation of spaces. Plant form one way of achieving the design element of form.

Plants forms can also:

- convey a sense of energy

- draw the eye in a particular direction.

Plants that have an upright form, like columnar, conical, vase-shaped, and multi-stemmed trees, draw the eye upwards and create a feeling of high energy. On the other hand, plants that have a weeping shape draw the eye down.

Weeping, rounded, spreading, and horizontal forms give off a more subdued energy.

Vertical forms have a higher visual weight, meaning they are more dominant, so the eye is drawn to them.

Knowing this means we know the type of plant forms that will best suit different areas of our garden. For instance, we might choose to plant vase-shaped trees, and upright shrubs, perennials and groundcovers in the gardens that wrap around a large lawn intended for the kids to play on. Likewise, for the gardens that enclose a small pergola for reading and meditation, weeping, rounded, or spreading trees with rounded and horizontal shrubs, perennials and groundcovers would be more appropriate.

Activity: Impact of plant form

|

|

| The image on the left shows upright plants and a vase shaped tree which gives a sense of high energy and desire to be active. In the right hand image, if you look to the back of the site you’ll find weeping trees and rounded and horizontal planting which creates a feeling of relaxation. | |

Design elements

You will recall that the design principles are the overarching rules or guidelines to follow, and the design elements are the components of the design that are used to stick to the ‘rules.’ We’ve already talked about five design elements – line, shape, form, space, and rhythm – but there are two more: texture and colour.

We’ll introduce texture and colour as they relate to plants, but these design elements also apply to hard landscaping.

Texture

Texture refers to the smoothness of a surface or object. In our case we are most concerned with the leaves, or foliage, of the plant.

Texture size

Where the leaves are very small, we say the plant has a fine texture. Where they are very large, we say it has a coarse texture. Where the leaves are in between fine and coarse we simply talk about the plant having a medium texture.

Coarse texture plants have a high visual weight and a stronger energy.

Texture is relative, meaning that in a garden that uses only plants with large leaves there will still be texture variation. The plants with smallest leaves will be treated as fine texture and the ones with the largest leaves will be treated as coarse texture. Those in the middle will be treated as medium texture.

This greenwall shows a range of textures. From the large leaves at the far right and the branched leaves at the bottom left (coarse), to the small leaflets of the ferns (fine), to much of the rest, which can be thought of as medium texture.

Texture shape

When people talk about plant texture, most likely they’ll be referring to texture size, but the shape of the foliage is important too. We call this texture shape.

We are only interested in specifying texture shape when it is different to what is normal, in other words, if it needs to be particularly round or linear (straight).

Texture as a design element

We can use texture to trick the eye. If you want to make a space feel larger, use fine texture plants at the back, medium in the middle and coarse texture plants at the front. This makes the plants at the back feel further away. For a space that you want to feel smaller and more intimate, use the opposite: fine plants in the front and coarse plants at the back.

Texture relates to hard landscaping materials too. For example, you may choose to use aggregate that is coarse, medium, or fine on a pathway.

Natural stone or urbanite paving will add texture to the garden too. Whether we treat it as coarse, medium, or fine will depend on the size of the units used and the spacing between as well as the size of plant foliage in the garden.

In this garden the coarse texture is provided by the rocks with the plants categorised as either fine or, in the case of the large glossy leaves, medium texture.

Colour

“Color is the characteristic that most people notice first in a landscape, and it is also the characteristic by which most people select plants. However, designs based on color often fail because color is fleeting” (Hansen and Alvarez, no date). A better approach is to select plants firstly for their size, form, and texture and choose colour last. This will ensure that the garden looks good year-round.

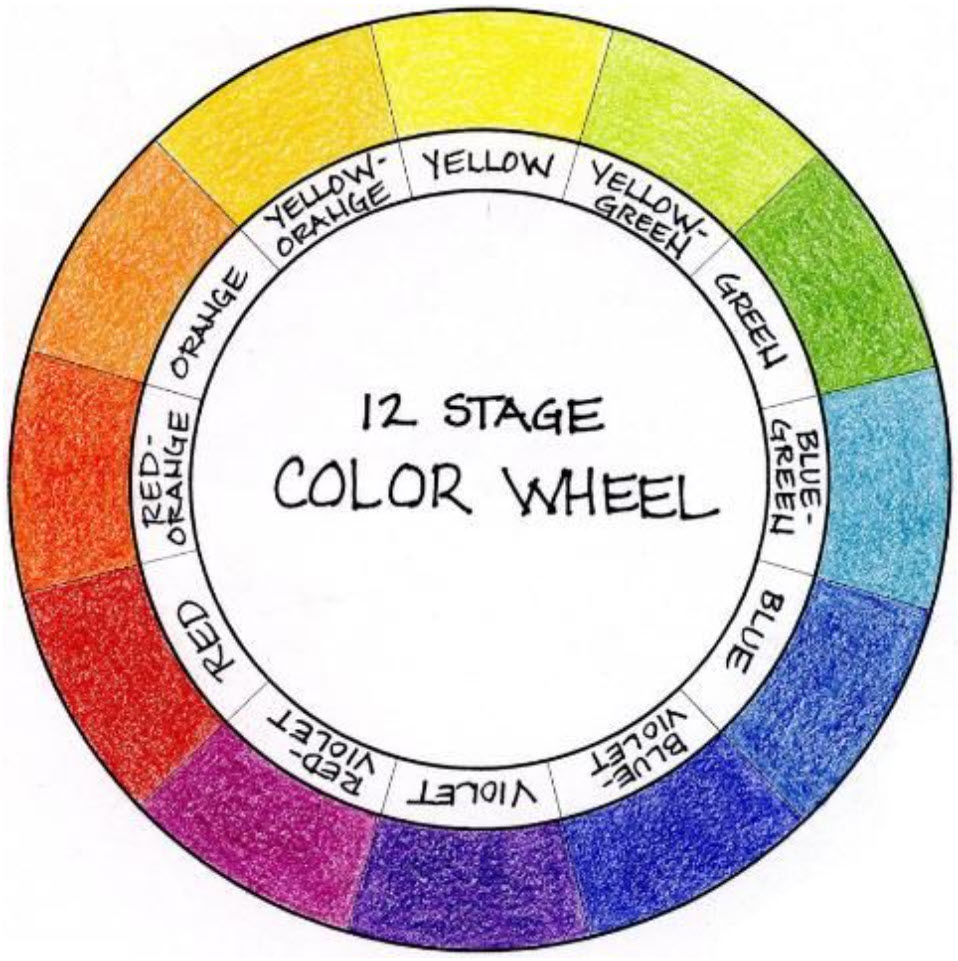

That is not to say that colour isn’t important. It is. Like with all other aspects of garden design, we want our colour selections to meet the principles of unity and simplicity, by settling on a colour theme. To do this well, we need a basic understanding of colour theory.

Read: Color in the landscape: Finding inspiration for a color theme (5 minutes)

This article provides a quick overview of colour schemes for garden design, the properties of different colours and key considerations when choosing a colour scheme.

Read the article down to and including the section called Things to consider when choosing color.

Pre-Read Question: Has your client told you what colours they want to see in their garden? Have you thought about how you will incorporate these into the design?

Color in the landscape: Finding inspiration for a color theme

(Source: University of Florida)

Post Read Task: Which of the colour schemes described in this article seems most appropriate for the garden you are designing?

If you’re interested in seeing what some of these colour schemes look like, have a look at this blog post by landscape designer Sue Gaviller: Colouring Your Garden – Part 9: Colour Schemes. Sue covers a larger range of colour themes, but we recommend focusing on the first three (monochromatic, complementary, and analogous) and using one of those methods for your garden design.

Colour as a design element

Where colour is being used, the brightest brights and darkest darks have the greatest colour weight so these should be used for when you want to draw people’s attention. The same is true for hard landscaping elements. You might, for instance, decide that a gate or archway needs colour in order for it to become a bold focal point. The colour you choose should link to your chosen plant colour scheme.

When choosing plants for their colour, consider:

- As a general rule, gardens should be 90% foliage (generally green) and only 10% other colours, by way of flowers and fruit. Too much colour will overwhelm the viewer.

- Cool colours make a space feel larger and warm colours make the space feel smaller.

- White flowers are often added to other colour schemes as somewhat of a blending colour.

- Not all plants will flower, bear fruit, or put on a colourful foliage display at the same time as each other. However, sticking with a colour scheme will mean that whatever time of year they do, the garden will feel unified.

We’ll talk more about how to arrange plants based on the different colour schemes later in this module.

Activity: Plant characteristics

Check your understanding of colour schemes by completing this quiz. You might like to refer to this 12-stage colour wheel by Gail Hansen.

A note about the colour white — white is generally not mentioned in colour scheme names, but could be described as an addition, such as: “Blue, blue-violet, violet, red-violet analogous with white.”

In this topic we’ve:

- looked at what plants actually need for healthy growth

- introduce a range of plant features that we can use to help us choose plants that complement each other.

In the next topic we’ll learn how best to arrange plants to look good in the garden.