Video Topic introduction – Script

This short topic is designed to assist you with mastering your online research and report writing skills. By the end of this Level 5 Diploma, it is expected that you will be able to demonstrate a solid grasp of technical, operational, and theoretical knowledge within the field of sport and exercise science. While you will be taught a wealth of valuable content in both face-to-face and online classes, a big part of your development will come from learning to research independently.

The NZQA descriptors for Level 5 emphasize the ability to navigate complex information and apply it to practical situations. This topic will guide you in this learning process. You’ll be honing critical skills to distinguish high-quality information from unreliable sources and develop a clear understanding of how to use this information effectively in your reports and assessments.

This topic is all about taking control of your learning.

- You will improve your ability to find high-quality sources by learning how to use online databases to access reliable primary and secondary sources that will allow you to reach evidence-based conclusions.

- You will learn how to navigate scientific studies, developing strategies for reading and analysing scientific articles to pull out key findings.

- You will also learn how to use and reference the information you find appropriately in your reports (avoiding plagiarism).

These are essential skills not just for this module, but for your future career in the sport, recreation and exercise industry. Whether you’re investigating the impact of training programs, studying the physiology of athletes, or looking into new trends in exercise, the ability to find and use quality research is critical.

Even though this topic is theory-based, it’s packed with practical learning tasks that let you apply what you’ve learned. You won’t just be sitting back and reading—you’ll be actively working on research tasks, putting theory into action as you prepare for your assessments.

Your first opportunity to try out these new skills will come around quickly! You’ll soon be diving into Module 2 Assessment 3, where you’ll be asked to analyse the effects of exercise on physiological functions in sport, recreation, or exercise contexts. You’ll gather evidence from scientific articles, draw meaningful conclusions, and deepen your understanding of how exercise influences human physiology. This will be your opportunity to apply your new research skills.

We’ll kick things off by reviewing what you’ve covered in face-to-face lessons this week, and then move on to learning new research skills. By the end of this week’s online session, you’ll have chosen your topic for the report and started collecting evidence.

So, dive in, get curious, and enjoy this exciting journey into research!

It is important that when gathering information to use in an assessment report, that you only use information that is from reputable sources. A reputable source is one that has produced or reported evidence applying strict quality control measures.

In your face to face learning this week, you were introduced to different sources of information. You also applied some checking questions that can be used to assess the quality of article. Let’s see what you have been able to retain from that learning.

H5P here

When is it ok to use articles or opinion-based articles sourced through a normal Google search?

While the majority of information you source for your assessments should ideally come from primary sources, or high-quality secondary sources, there are times where using information from an interesting online article is ok too.

These types of articles can be useful in establishing a context in a report, or to draw the reader in. For example, in your face-to-face lesson you were introduced to a news article about red wine and how it might be able to replace exercise for cardiac health. While the information in the article was essentially rubbish, it did provide an interesting context for the discussion and learning that followed. It was also a more interesting way to start the learning, than simply talking about resveratrol and how rubbish the report is. I’m sure some of you wanted the claim the article was making to be true!

General online searches are a great way to find out what is being said about a given topic. They can be useful to use in a report’s introduction to create interest before you dive deeper to find the answer to the question your report is trying to uncover. Claims made in online articles that have no sources provided or clear evidence to back them up are fine to use but should be presented as “evidence”.

What about reputable organisations that write articles or recommendations (but don’t provide sources for their information)?

Let’s say the NZ Stroke Foundation released a set of recommendations for assisting a stroke victim to regain function in the year after a stroke, but there were no references given for the information provided. Can you trust the information? In short, yes.

Sometimes you simply need to make a judgement call on the reputability of the organisation. National organisations and Government organisations (like the Ministry of Health) are generally classed as trustworthy organisations.

If the articles they produce give an author, look them up to establish their level of expertise. You will often find these organisations have some of the brightest minds in areas related to the organisation working for them. However, often they don’t provide an author for the information.

These organisations should provide their sources, however, as long as you attribute the information you used to these organisations, that’s fine. It obviously wouldn’t hurt to add additional findings from other reputable sources to corroborate the findings.

Validity

When providing evidence in your academic reports, you may be asked to address the validity of the sources you have used. Regarding evidence, validity essentially is a measure of how well the study measured what they were trying to find out, and how usable the evidence is, and how it can be applied outside of the context of the study.

For example, a research experiment conducted on 6 people wouldn’t hold as much weight as one completed on 6,000 people. Similarly, if the subjects of a study were all of the same gender and age, can we apply the learnings from the study to other populations?

Scientific studies have to address the validity of their study in a section of their report. This section is usually called “limitations”. In this section, the authors are supposed to write about who the evidence applies to and who it doesn’t. They must also disclose any factors that may have influenced the results of the study. The authors must also disclose if there are any conflicts of interest that are related to the study. For example, an author may work for a company that may benefit from the study findings.

When you are addressing the validity of the sources you have collected evidence from, you should consider:

- The quality of the source – primary, secondary etc.

- The author/s of the article – level of expertise, experience etc.

- The reputability of the publication – peer reviewed journal, newspaper article, blog etc.

- The range of people included in the study (age, gender etc.), sample size and duration of the study.

- The methods used to produce results in the study.

- Any validity issues or conflicts of interest raised by the authors.

Knowledge Check

Answer the following questions to show you have taken on board the information covered above.

H5P here

The following task is a “choose your path” scenario designed to put your knowledge of information source selection to the test. See if you can get to the end of the task by choosing the right answer at each step. Be careful! If you give a wrong answer, you will be taken back to the start of the journey!

The point of conducting online research is to answer a question. In the case of assessments, the questions are dictated by the tasks. When assessment tasks call for evidence-based answers, you need to conduct your own research to search for evidence. To gather evidence from academic articles, you need to know how to read them!

You now know how to find high-quality articles to use in your assessment reports. Finding them is one thing, reading and understanding them is another! Often you are only after a small amount of information, but the article includes pages of dense academic writing. This section is designed to help you navigate these articles to find the information you need. There are a few different types of articles you may come across in your online research. Let’s start with the most common. Academic journal articles reporting the findings of a study or experiment.

Reading Academic Journal Articles

All journal articles that present a scientific study are formatted in the same way. Each article is broken into the following sections:

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Methods

- Results

- Discussion – including limitations

- Conclusions

Let’s take a brief look at each of these sections in turn. In the learning that follows, you will be introduced to the sections involved in an academic journal article. Each section introduced will include a reading task designed to get you familiar with the way in which these sections are presented. A critical skill in academic research is the ability to scan articles to find the critical information you need. This skill requires you to be able to filter through some of the higher-level academic writing to find the elements of the article that will be useful to include in your assessment (while still understanding the context of the article).

What follows is a series of these reading tasks where you will be asked to read sections of different academic articles to find specific information. Up first, the article abstract.

The Abstract

This one you have already come across. An abstract is provided at the very start of each academic journal article. It is a brief overview of all parts of the article. In it, you should be able to find out key information that will let you know if this is an article worth reading further, i.e., might it help you answer the question you need to answer for your assessment? A quick scan of an abstract should tell you what the purpose of the study was, how they conducted the study (and on who) and what the results of the study showed. It should finish by giving the author’s conclusions and/or recommendations based on the findings.

The passage below is an abstract taken from a journal article called “The Effect of Music on Anaerobic Exercise Performance” written by T. Attan (2013). The paragraphs in the abstract have been mixed up! Drag the paragraphs into the correct order, then read the abstract and answer the questions that follow.

If we can’t use this, then simply pace the abstract text in an emphasis box and change the instructions above to “Read the abstract and answer the questions that follow” (then jump straight to the question set below).

H5P here

The Introduction

This segment of the article outlines the purpose of the current study (this may be given at the start or end of the introduction). It also gives some background or context to the study by introducing findings from previous (related) research. An introduction should also introduce any key concepts a reader should understand before reading the results of the current study. This may include specific terms of reference or abbreviations that will be used throughout the article.

Introductions can be quite lengthy, depending on the amount of previous research they decide to discuss. Often, because the authors of the current study are using multiple research sources, they will summarise the findings of multiple studies that found similar outcomes. They indicate the sources they have used by bracketing the numbers which correspond to the order in which the sources are presented in the post text referencing section, e.g., (3,4,11,13) is saying that the sources the information came from was from source number 3, 4, 11 and 13 in their reference list at the end of the article.

The key to reading an introduction is to develop the ability to skim read the text to understand what the context of the current research is (and what previous research has found). Let’s work on this skill now.

Below is an example of an Introduction from an article by Arnett (2001) entitled “The Effect of a Morning and Afternoon Practice Schedule on Morning and Afternoon Swim Performance”. Read the introduction and answer the questions that follow.

The Effect of a Morning and Afternoon Practice Schedule on Morning and Afternoon Swim Performance.

Mark .G. Arnett (2001).

Introduction

Maximal human effort is the goal of every athlete. However, the performance of physical tasks appears to vary with the time of day (2, 4, 10, 16, 17). The theoretical basis for the effect of the time of day on training centers in the circadian rhythms are demonstrated in many physiological variables, especially within the body-temperature curve (2, 17). Body temperature falls to a minimum around 0400 hours during sleep and begins to rise before waking. The rise usually continues until the peak of the rhythm is reached at around 1800 hours (2).

Self-rated perceived exertion (6) may be sensitive to circadian variability. Diurnal variation of the rate of perceived exertion (RPE) has been reported with minimal values occurring in the afternoon (8, 11). Hill et al. (9) also reported a diurnal variation of the RPE effect, however, minimal values occurred in the morning. Other investigators have indicated that RPE is resistant to circadian variability (14). The variability in RPE will have a direct impact on the capacity of the athlete to sustain maximal exertion.

Freestyle swim times of 100 and 400 m were observed to peak at 2200 hours in 4 men and 10 women competitive swimmers (mean age 14.7 years; 3). Performance showed a significant linear trend with the time of day in close, although not exact, association with the circadian rhythm in oral temperature. The steady improvement throughout the day was 3.5% for the 100-m and 2.5% for the 400-m swims. Rodahl et al. (15) found that 100-m swimming performance was better in 3 out of 4 strokes in the evening (1700 hours) compared with the morning (0700 hours). Participants included 10 men and 13 women swimmers who ranged in age from 11 to 23.

On the other hand, Conroy and O’Brien (7) reported no significant difference in 100-m swim times between morning (0700–0800 hours) and evening (1700–1900 hours) of the same day among Olympic and intercollegiate swimmers. In all 3 studies (3, 7, 15), the competitive swimmers habitually trained in the morning and in the evening. Although the swimmers had a morning and afternoon practice schedule, specific data regarding intensity, volume, and frequency were not reported. Furthermore, the investigators did not state whether practice and the swimming performance occurred at the same time of day.

It has been speculated that performance at a particular time of day will be greatest if the training has occurred at that time of day. Torii et al. (16) had participants train aerobically for 4 weeks either in the morning, afternoon, or evening. Pre- and post-testing was conducted in the afternoon at the same time of the day as the afternoon training sessions. The afternoon group was the only group to demonstrate a significant improvement in VO2max. It could be inferred from the results that VO2max improved when measured at the same time of day as the training.

Hill et al. (10) took this inference a step further and demonstrated that improvement in work capacity in high-intensity exercise occurred at the time of day of training (morning and afternoon). Nevertheless, in the Hill et al. (10) study, the afternoon group improvement was significantly greater than the morning group. However, neither Torii et al. (16) nor Hill et al. (10) used a morning and afternoon practice schedule.

Swim meets usually consist of preliminary heats in the morning and finals in the late afternoon. Therefore, swimmers must be able to exert maximal effort in the morning and late afternoon. The evidence to date indicates that there is temporal specificity when training; work capacity is at high intensity (10) and VO2max (16) demonstrate the greatest improvements in the afternoon. However, there is a lack of evidence regarding the effect of a morning and afternoon practice schedule on morning and afternoon maximal effort.

The development of data from this study will add significant information to the limited database on morning and afternoon maximal performance. The greater the understanding of the circadian rhythm, the better-informed coaches will be and the knowledge they apply to training programs. The purpose of the investigation was to examine the effect of a morning and afternoon practice schedule on morning and afternoon swim performance.

H5P here

Methods

This is where the experimental design for the study is detailed along with information on the subjects (if any) that participated in the study (age, gender, etc.) This section will outline the different groups or processes used during the study investigation, what the groups had to do, along with how frequently and how long they had to do it for. It will also outline any measures or measurement techniques used for collecting data during the study and discuss how the data was used.

Below is a link to an article by Correia et al (2020) entitled “The Effect of plyometric Training on Vertical Jump Performance in Young Basketball Athletes.” By clicking on the link, you will download a PDF of the full article on your computer. Navigate to the “Methods” section in the article. Keep this article open while you answer the questions below (look at a question then scan the article to find the answer).

Reading

Article Title: The effect of plyometric training on vertical jump performance in young basketball athletes

Read time: 3 minutes

Article Summary: This is a link to a full article that reports on an experiment where the authors looked at the effect of plyometric training on vertical jump in young basketballers.

Pre Read Question: Keep this article open while you answer the questions below (look at a question then scan the article to find the answer).

Source: Journal of Physical Education

H5P here

Results

This is where all results from the study are detailed. This section usually includes diagrams and graphs to illustrate the results. The results section is often quite detailed and complex, and data is typically presented without any context or discussion. While you are likely interested in the results of a study for your assessment, it is often better to read what the results mean from the perspective of the authors as this will include some context and discussion that will make the results easier to absorb and understand. This information can be found in the next section – Discussion.

Discussion

In this section the authors discuss the results and give some context to them in relation to the question the research was designed to answer. The authors may also compare their study’s findings, to the results of previous studies completed on the same (or similar) topics. This section often includes “practical applications” to let people know how the results of the study might be used by people in industry (i.e., what it might help them to do).

The discussion section from a study by Esmarck et al (2001) has been detailed below. This experiment was conducted to explore the effect of post exercise protein timing on muscle hypertrophy in elderly humans. In the study, 13 over 70 males did 12 weeks of resistance training. Half received a protein meal immediately after the exercise session, while the other half had the same meal 2 hours post exercise. The passage below discusses the results of the experiment.

Read the discussion passage from the study, then answer the questions that follow.’

Discussion

The major finding of the present study is that the timing of protein intake after resistance training bouts in elderly males is of importance for the development of hypertrophy in skeletal muscle. Thus, over a 12-week resistance training period, the cross-sectional area of the quadriceps femoris and mean fibre area increased by 7 and 22 %, respectively, when protein was ingested immediately after exercise, whereas no significant changes were observed when protein was supplemented 2 h postexercise. The degree of hypertrophy found in the group who immediately ingested protein was similar to the findings of other studies investigating the effects of resistance training in the elderly where no specific dietary restrictions were reported (Frontera et al. 1988; Brown et al. 1990; Fiatarone et al. 1990; Welle et al. 1996). In addition to the difference in hypertrophy development between the two groups, it is interesting to note the absence of any detectable hypertrophy in the 2-hour delayed group despite 12 weeks of resistance exercise identical to the immediate protein ingested group. This points to the importance of the early timing of protein intake in recovery from resistance exercise in terms of the amount of net protein synthesis in skeletal muscle.

Such a hypothesis somewhat resembles the findings of the importance of early carbohydrate intake for the magnitude of glycogen resynthesis after exercise-induced depletion of muscle glycogen (Ivy et al. 1988).

The increase in mean fibre area was more pronounced (22 %) than the cross-sectional area (CSA) of the whole muscle (7 %). This is in accordance with the findings of other groups (Frontera et al. 1988) and reflects a reduction in the relative amount of non-muscular tissue (fat and connective tissue) which mediates the CSA that takes place in response to training. This is supported by findings in resistance-trained fragile elderly women, where a 10 % increase in CSA of quadriceps was measured when corrected for fat and connective tissue versus only a 5 % increase when not corrected for this (Harridge et al. 1999).

The mean fibre area of type 1 muscle fibres was found to be larger than in type 2 fibres when baseline levels were tested. This is in agreement with previous observations in the elderly (Lexell et al. 1983; Aniansson et al. 1992). However, with the training type 2 fibres increased in size significantly more than type 1 fibres. These changes with resistance exercise are similar to findings in both young (Andersen & Aagaard, 2000) and elderly individuals (Charette et al. 1991) and could indicate that training induces a larger increment in stress of the type 2 fibres than type 1 fibres compared to normal daily living (Henneman et al. 1965). Further, it was only the area of type 2a fibres that increased significantly. In addition, lean body mass increased more in the immediate protein ingested group than in the 2-hour delayed ingestion group, in agreement with a larger net muscle protein synthesis in the immediate ingestion group over the 12-week period of resistance training compared to the delayed ingestion group.

No significant differences were observed between groups for any anthropometrical, dietary, muscle or strength parameter before training (see Table 1). Hence, both groups fulfilled the recommended daily allowance for energy and protein intake and also met the more extensive protein recommendations for the elderly (0.9 g kg−1 day−1; Campbell et al. 1994).

The difference in hypertrophy between the two groups suggests that the isolated act of contraction is counteracted by other factors, e.g. delayed food intake. In line with this, Tipton et al. (1999) have shown that postexercise net muscle protein balance is negative when individuals are maintained in the postabsorptive state during recovery, whereas if they ingest protein and achieve hyperaminoacidaemia the protein balance becomes positive. Finally, we are confident that both groups trained properly as the training sessions were always supervised and loads adjusted at every third training session. This is supported by the increased training strength (5 RM), which was observed for both groups.

Although not directly measured in this study we do believe that the protein intake highly stimulated muscle protein synthesis, since in a recent study by Rasmussen et al. (2000) protein synthesis was elevated 3.5 times above pre-intake values when a supplement of only 6 g amino acid with 35 g carbohydrate was ingested, whereas we gave 10 g protein together with 7 g carbohydrate. Moreover, since amino acid delivery is dependent on blood flow (Biolo et al. 1995), the intracellular amino acid availability in the exercised muscle may have been larger in the immediate ingestion group than in the delayed ingestion group as blood flow was still elevated in this group, but not so in the delayed ingestion group.

Altogether, our findings suggest that the first 2 hours of recovery after resistance exercise are important for the net protein synthesis during a strength-training programme evaluated over a period of time, and to optimise the protein synthesis the intramuscular concentration of free amino acids is critical if it is not to be a limiting factor.

In the present study muscle fibre hypertrophy was more pronounced in the immediate ingestion group than in delayed ingestion group despite identical rises in plasma insulin after the intake of a supplement containing protein and carbohydrate. However, it may be speculated whether the insulin sensitivity of protein turnover is markedly higher immediately after exercise than 2 h later. This has, however, to our knowledge not been studied in humans.

Finally, we cannot exclude the possibility that our finding of a difference in hypertrophy between the groups is a result of the relatively low number of subjects. However, no subjects were systematic outliers and, furthermore, all subjects in the immediate ingestion group had a larger increase in the relative change of the CSA of the quadriceps than any subject in the delayed ingestion group. Additionally, theoretically it cannot be ruled out that exercise-induced changes in tissue and serum levels of anabolic hormones such as growth hormone, cortisol or insulin-like growth factor 1, which were not measured in the present study, could contribute to the difference between the results of the groups.

H5P here

Information relating to limitations may be a section on its own or could be included in the discussion section of an article (as it was in the article above). This is where the authors raise any concerns around the way the experiment was conducted, (the methodology) or the subjects used in the study that may have influenced the results. The authors also have to state any conflicts of interest that may cause bias towards finding a particular result. For example, if a hydration study was funded by Gatorade and concluded that Gatorade was the best sports drink for replacing electrolytes, this would be a conflict of interest.

Conclusion

This is where the authors sum up their findings and make suggestions for further areas of study. This is where the answer to your question will likely be found. The conclusion will provide one of these two common scenarios:

- A clear result from the study that answers the research question being asked with clear recommendations for how that information might be used, i.e., the results of the study suggest, or appear to suggest that…

- An unclear finding, or one of limited significance with a suggestion that further study is required in this area.

Here is an example of a conclusion statement. It is the conclusion from the experiment on protein ingestion timing on hypertrophy in elderly subjects. The authors are pretty confident in their findings!

In conclusion, this study investigated the importance of the timing of protein intake after each exercise bout over 12 weeks of resistance training on morphological and strength characteristics of skeletal muscle in elderly individuals. Based on the findings in the present study it appears that the timing of protein intake after strength training bouts can be important for protein synthesis and hypertrophy of skeletal muscle in elderly individuals. The present findings support the hypothesis that early intake of protein after resistance exercise enhances total muscle mass as well as hypertrophy of single muscle fibres in elderly humans.

Recap of learning

The following task is designed to check your understanding of how to navigate a journal article to find specific pieces of information related to a study. Each flash card in the task below will ask a question. The answer to each question is one of the article sections we have discussed above. Type the article section you believe answers the question into the space provided on the flashcard. Note: you only need to type one of the following words (without “the” in front of it).

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Methods

- Discussion

- Limitations

- Conclusion

H5P here

Time to put it all together and have a crack at a full academic article. Below is a link to an article published in the Journal of Physiology. This article is also related to protein ingestion post exercise but has a slightly different focus. This experiment by Areta et al (2013) wanted to know if the manner in which protein was ingested following resistance training impacted on muscle fibre protein synthesis (growth).

Click on the link and download the article onto your computer. Have the article open in another window. Rather than read the article in full. Begin reading the question below then navigating to the appropriate section of the article and skim read until you find the information you are looking for. Type the answer into the passage when you find it.

Reading

Article Title: Timing and distribution of protein ingestion during prolonged recovery from resistance exercise alters myofibrillar protein synthesis

Read time: 10 minutes

Article Summary: This is a link to a full article that reports on an experiment where the authors looked at how different protein consumption practices post resistance training affected muscle fibre growth.

Pre Read Question: Keep this article open while you answer the question below (look at a question then navigate to the section of the article to find the answer. Once you have the answer, write it in the space provided in the question below.

Source: The Journal of Physiology

Scan the relevant section of the article to find the answers that will complete the following passage of writing.

Could it be possible for a secondary source to be an even better source of information that a primary source?

Actually, yes!

Remember, most experimental studies have their limitations. For example, the two protein articles we have used in our online learning today were both small studies (13 and 24 subjects respectively). The first study was conducted on older people and the 2nd was on young healthy males, so quite a limited age range. If only someone who was an expert in the subject had read all the available articles, screened them for quality, and then written some conclusions considering all the available evidence.

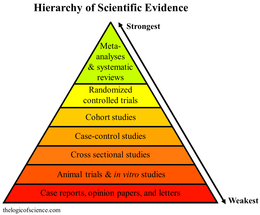

Wait….in many cases they have! Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are considered more reliable and valid than independent singular experiments.

Systematic Reviews

A systematic review aims to answer a research question by identifying, critically appraising and synthesising relevant primary evidence. A systematic review has 4 main objectives:

- It surveys articles from the available evidence in your chosen area of study, applying a strict list of criteria to ensure only the most robust and valid studies are included.

- It collates the findings of the remaining studies into a summary.

- It critically analyses the information gathered by identifying gaps in current knowledge; by showing limitations of theories and points of view; and by formulating areas for further research and reviewing areas of controversy

- It attempts to answer the research question and present the literature in an organised way.

Meta-Analyses

Similar to systematic reviews, meta-analyses assess previous research, but they focus more on the quality of data obtained from research. A meta-analysis takes the results of a number of studies trying to answer the same research question. They apply statistical processing formulae to determine the effect size across the studies (taking into account the strengths and weaknesses of each study included). This is useful in subjects where a lot of conflicting evidence exists. It takes the subjective elements of studies out of play by focusing only on what the data says.

Meta-analyses can be stand-alone articles or can be conducted as part of a systematic review.

How do you find and use them?

This short video explains how you can find systemic reviews and meta-analyses using Google Scholar and the differences in structure (sections) between these documents and the articles you have already practiced with.

Video Title: Systematic Review and Meta Analyses

Watch Time: 13:30

Video Summary: This short video explains how you can find systemic reviews and meta-analyses using Google Scholar and the differences in structure (sections) between these documents and the articles you have already practiced with.

Source: YouTube

Now that you have the knowledge to locate high quality information sources (and read them), you are ready to be introduced to the first assessment that you will use these skills for. While we have a number of key skills still to learn, we will introduce them as they are needed to complete tasks in the assessment. You are now able to choose a subject to research and source high quality evidence from academic articles. Once you have found suitable articles, we will learn:

- How to use the information you find in online sources in your report; and

- How to reference the information you use in your report.

Assessment 3 is a written case study report that requires you to conduct online research (using the techniques we have just learned) to locate and analyse three high-quality sources of information that will help you to answer a specific research question.

Your research question must examine the effect of exercise on a particular function within the body. This is as simple as choosing a type of exercise you are interested in and then finding evidence for how it affects a particular system of the body (and its function).

There are obvious topics like the effect of a particular resistance training mode on muscle fibres, or the effect of a cardio training mode on the heart, through to less obvious topics like the effect of an exercise mode on the brain, digestive system or specific hormones. More on this shortly.

Assessment 3 – Task overview

While you will get a full explanation (including guides and tips) for each task and sub-task of this assessment, it doesn’t hurt to have an overall idea of what is expected from you for this assessment. The three tasks that make up this assessment are briefly described below.

Task 1 - (Select a Research Question and Perform Online Research)

In this task, you must decide on a research question, then locate evidence from THREE high-quality sources of information that will help you determine the effect of exercise on a particular physiological function in the body. This will involve using the skills you have learned in this week’s online lessons to locate scientific journal articles and determine if they are appropriate to use in your assessment.

Task 2 – (Written summary of findings)

This task makes up the main body of your report. You must provide a written summary that integrates the evidence collected from your three sources of information in relation to the effect that exercise has on your chosen physiological function. This is where you bring the evidence you have collected in your online research together to give a clear picture of how the mode of exercise affects the system (or function) you have chosen. This task is written up using a structure similar to the articles you will source including an introduction, summary of findings, limitations statement and conclusion.

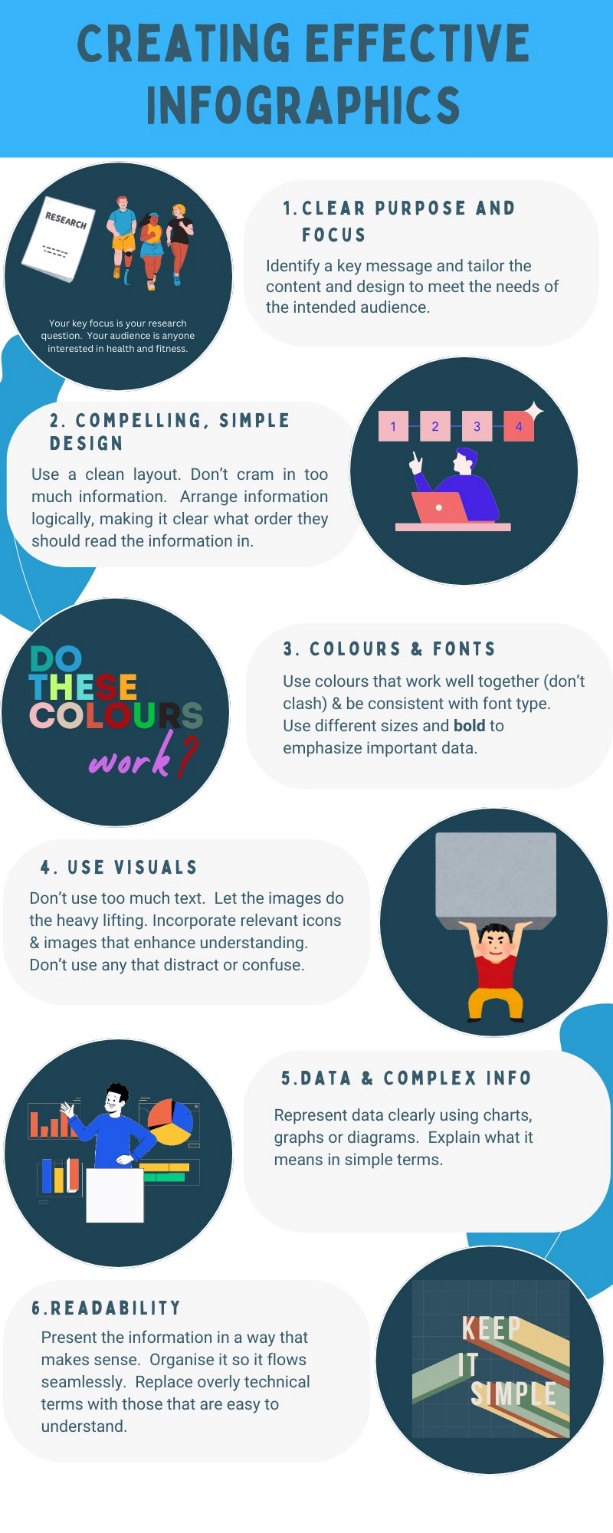

Task 3 – (infographic/poster)

The final task is to turn the information you have produced into an engaging and informative infographic that presents the evidence of your research into the effect of exercise on a particular physiological function (in language that the general public will understand).

Ready to make a start?

Now that you have practiced finding and reading quality academic articles you are ready to make a start on the first task of Assessment 3.

Create a new copy of the Level 5 written report template document you were introduced to in Module 1. Complete the title page (this assessment is Module 2 – Assessment 3). Create a sub-heading for task 1.

Task 1

Task 1 of your assessment is completed in two parts:

The first step is to choose a research question. To keep your interest levels high, it helps to choose a question that you actually want to know the answer to. Here are the criteria you must adhere to in selecting your research question.

1.1 Decide on a research question you are interested in finding out the answer to. This question must be related to an acute or chronic effect that exercise has on a physiological function in the body. Your research question must:

- Be clear and concise

- Include one form of exercise or physical activity

- Include one physiological function performed by the body

To help you understand what it is you have to do to successfully complete each task, we will use a series of exemplar answers. The research question we will use to do this is:

“Can doing regular resistance training alone cause positive changes in cardiovascular health?”

This question is clear and concise. The form of exercise chosen is resistance training. The physiological function chosen is the function of the cardiovascular system.

Your Turn!

The table below provides a range of exercise/activity modes along with a list of potential systems you could choose to base your research report on. Time to choose a research question. Once you have decided on a question, it is important to check the question with your tutor in your next face to face lesson (so that no one else chooses it first).

| Potential Exercise /Activity Lists | Potential Physiological Systems or Functions |

|---|---|

|

|

The second part of task 1 involves getting online and searching for high quality information sources that will assist you in answering your research question. Here are the task criteria for the selection of your sources.

Task 1.2 (a)

Locate THREE high-quality information sources that will help you answer your research questions. These information sources must:

- be primary or high-quality secondary sources of information only.

- include one systematic review or meta-analysis (if available).

- be full text (not abstracts)

- be closely related to the research question.

- be published post the year 2000.

Search Wording

Getting the wording right for your search on Google Scholar can save you some time. Many of the types of articles you will be looking for start with the wording “The Effect of…..”.

This is a good place to start with the wording of your search. For example, if you were interested in how tendons are affected by ultra-endurance training, your search wording would be “The effect of ultra-endurance training on tendons”.

Remember, by adding the words “systematic review” or “meta-analysis” at the end of your search wording, Google Scholar will try to include these in the results.

An initial search will let you know if your chosen topic has enough recent research to use to complete the assessment tasks. If your initial search doesn’t yield the types of articles you are looking for, try adjusting your search wording. If that also fails to yield results, consider changing the topic slightly.

Selecting Articles

The first step in selecting an article for your assessment is to read the abstract. Find out who the study was conducted on (sample size), what the methods used were and read the findings (conclusions). If the article looks like it will be helpful in answering your research question, copy the link and paste it in your assessment report template (for easy access later). Continue with this process until you have 4-5 good article options for your assessment. You can then spend a little time reading the key parts of each article to see what additional information you can find related to your question. During this process, it should be clear which THREE articles are the best fit for your needs.

When deciding between two articles consider things like:

- How recently the article was published

- The number of participants used, or studies reviewed in the article

- The specific measures used in the article (and how well they relate to your research question).

Time to get started! Decide on a research question, then complete your online search for three quality articles (including a systematic review or meta-analysis) before continuing with your online learning for the rest of this week. Your tutor will want to know your research question and see what articles you have sourced in the final face to face class of the week.

Task 1.2(b)

The final part of task 2 requires you to write a brief description of each of the articles you have chosen to use in your assessment. Here is a breakdown of the task.

1.2 Provide a brief description of each information source you have found that covers the following:

- The title of the article along with the author/s, date and publication source.

- The type of article it is along with details of the methodology used.

- The reason you have selected this article (i.e., how it relates to your research question).

Each description must be at least 100 words.

Exemplar answer

Throughout this assessment process you will be shown an exemplar answer for each task that will provide you with clear expectations of the type of answer you need to produce to achieve the task.

Here is a reminder of the research question associated with the exemplar answer:

“Can doing regular resistance training alone cause positive changes in cardiovascular health?”

Here is an example task 1.2 answer:

The first article I have chosen to include is a systematic review and meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine. It is written by Ashton et al (2018) and is entitled “Effects of short-term, medium-term and long-term resistance exercise training on cardiometabolic health outcomes in adults: systematic review with meta-analysis”. This review provides an overview of the findings of 173 different randomised controlled trials that looked at the effects of resistance training programs of over 2 weeks duration on cardiometabolic function in non-athletic populations over the age of 18. I chose this article because it includes the findings of a wide range of studies including subjects of both genders, so should give some pretty conclusive evidence of the effect of resistance training across the adult population. While the focus of this article is on cardio-metabolic effects, I will focus only on the cardiovascular functions as these are the focus of my research question.

The second article I have chosen to include is a randomised controlled experiment by Yu et al (2016) who studied the effects of a 10-week resistance training program on the cardiovascular health of non-obese adolescents. The article entitled “Effects of resistance training on cardiovascular health in non-obese active adolescents” was published in the World Journal of Clinical Pediatrics. In the study, 28 active boys and girls were placed into either a resistance training or control group. Those in the resistance training group did a 10-week supervised resistance training program. The groups were pre and post tested on a range of cardiovascular measures to see if the exercise had any positive effect on the cardiovascular system. I chose this article because it focuses on the adolescent population (which is a group not included in the systematic review above). The information from this article will allow me to apply my findings to a wider range of the population.

The final article I chose to include is entitled “Effects of Resistance Training on Arterial Stiffness in Persons at Risk for Cardiovascular Disease”. This was a meta-analysis focusing on the findings of 12 high quality studies including over 650 participants written by Evans et al (2018) and published in the Sports Medicine Journal. The average age of participants in these studies was over 60. This was the case because this group is particularly at risk of arterial stiffness. I chose this article because it focuses on the older population and those at risk of cardiovascular disease. I wanted to know if resistance training was beneficial (pr risky) for this population. It also increases the population range that my findings can include.

The remainder of your online learning and SDL time for this week is to be used to complete task one of Assessment 3.

The focus of your online learning and SDL this week is to prepare you for completion of task 2 of assessment 3. The skills you will need to learn to complete this task successfully are:

- How to use information sourced from scientific articles in your assessment report. This includes knowing how to paraphrase and re-phrase the information you want to use into your own words.

- How to integrate the information from multiple sources to form a cohesive discussion.

- How to reference the information you use (in-text) using the approved APA 7th edition reference style.

- How to use an online citation generator to create a post-text reference list using the approved APA 7th edition reference style.

- How to structure a summary of research in your assessment report.

Re-wording or Paraphrasing

So, you have found some great information that will help you to answer your research question. Copy, paste, done right? Unfortunately, that approach simply won’t cut it in Level 5. You need to re-word any information that you decide to include in your assessment reports. By what does re-word actually mean?

Re-wording or paraphrasing is when you take the meaning from what you have read in an external source, then frame it in your own words rather than using the exact wording used by the source document. It is essentially taking the “gist” of what the original source said but saying it in a slightly different way.

How to do it:

- Read the entire passage. Consider what parts you want to use (i.e., which parts actually answer the question asked in the assessment task). Think about what those passages are saying. Then write that in your own words.

- The key to making this authentic, is to write in your “own words”. This may require you to simplify words used from the original passage.

Here is a simple example of paraphrasing in action.

Original text

"Effects of High-Intensity Interval Training on Cardiovascular Function and VO₂ max in Athletes" by Billings et al (2016).

High-intensity interval training (HIIT) is an effective modality to enhance maximal oxygen uptake (VO₂max) and improve cardiovascular function. Our study observed that repeated short bursts of near-maximal effort followed by periods of low-intensity recovery increase both stroke volume and cardiac output in all study participants to some degree, but that this improvement was more pronounced in trained individuals. These improvements can be attributed to enhancements in myocardial thickness and contractility and increased peripheral oxygen extraction, resulting in greater delivery and utilization of oxygen by working muscles during exercise.

Paraphrased Text

HIIT is a great way to improve how well your heart and lungs work. This type of workout involves short bursts of very hard exercise followed by easier recovery periods. A study by Billings et al (2016) showed that doing HIIT regularly helped the heart muscle strength allowing it to pump more blood with each beat (stroke volume) and increase the total amount of blood the heart could pump to the working muscles (cardiac output) during exercise. Additionally, the ability of the muscles to use oxygen also appeared to increase. While these effects were observed in all subjects within the study, they were most noticeable in trained athletes.

As you can see, the paraphrased version captures the gist of the original paragraph but cuts out a lot of the unnecessary words like myocardial, contractility, peripheral, extraction and utilization, and replaces them with easier to understand terms that mean the same thing.

Key Messages for Paraphrasing

- Understand the original text: Before paraphrasing, make sure you grasp the meaning of the original passage.

- Use different words and structure: Change the sentence structure and replace technical terms with simpler alternatives where possible.

- Keep the original meaning: Ensure your paraphrase conveys the same key information as the original passage without altering its meaning.

Ready to have a go?

Read the passage of text below (taken from a scientific article). Try to understand the meaning of what the passage of writing is conveying, then attempt to paraphrase the text in your own words using the tool below the text.

Original Text – (excerpt from “Rest Interval Between Sets in Strength Training” by Salles et al (2009)).

When training for muscular strength with loads lighter than 90% of 1RM for multiple sets, 3- to 5-minute rest intervals are necessary to maintain the number of repetitions performed per set within the prescribed zone without great reductions in training intensity. On the other hand, contrary to what was observed in most of the experiments concerning muscular strength, some evidence suggests that 1-minute rest intervals allowed for sufficient recovery during repeated 1RM attempts; however, from a psychological and physiological standpoint, the inclusion of 3- to 5-minute rest intervals might be safer and more reliable. The acute expression of muscular power was best maintained when including 3- or 5-minute rest intervals versus 1-minute rest intervals between sets. When the training goal is muscular hypertrophy, the combination of moderate-intensity sets with short intervals of 30–60 seconds might be the best alternative, due to higher acute increases of growth hormone, which can contribute to the hypertrophic effect. Finally, similar to hypertrophy training, extremely short intervals (e.g. 20 seconds to a minute) between sets allowed for greater muscular endurance development. It is worth noting that, for any intensity or goal in strength training, the rest interval between sets may vary between practitioners of different ages, when the sets are not performed to concentric failure, according to the exercise and/or according to the athlete’s level of conditioning.

H5P Essay

Integrating information from multiple sources into one discussion

Integrating information from multiple sources in a report involves taking the key findings from various studies (or pieces of research) and weaving them into a cohesive discussion rather than presenting each source separately. This approach helps to create a well-rounded, comprehensive discussion of a topic, allowing you to compare, contrast, and draw conclusions from the research as a whole. Instead of summarising each article independently, integration focuses on connecting ideas and showing how the different studies relate to each other.

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to do this, followed by an example to illustrate how this works:

H5P here

Here is an example of integrating sources of information

I have located three articles to help me answer the following research question:

“How does high-intensity interval training (HIIT) affect VO₂max and cardiovascular function compared to continuous moderate-intensity training (CMIT)?”

I have read the articles and noted the key findings from each study. Here are the main details:

Source 1 Summary: A 2017 study by Jones et al. found that HIIT led to a 15% increase in VO₂max over 8 weeks, significantly greater than the 10% increase seen with CMIT. The researchers attributed the improvement to the higher intensity of exercise during the short bursts in HIIT.

Source 2 Summary: Smith and colleagues (2018) found that the HIIT participants showed a 12% increase in VO₂max over 6 weeks. However, the study noted that while cardiovascular efficiency improved more with HIIT, CMIT resulted in better long-term endurance adaptations.

Source 3 Summary: A review by Taylor et al. (2020) compared several studies on HIIT and CMIT. They concluded that HIIT generally produced faster gains in VO₂max but warned that the sustainability of these gains over long periods without continued training remains unclear, especially compared to the more gradual improvements seen with CMIT.

An integrated discussion

High-intensity interval training (HIIT) appears to be superior for short-term improvements in VO₂max compared to continuous moderate-intensity training (CMIT). Jones et al. (2017) reported a 15% increase in VO₂max in their HIIT group over an 8-week training period, while Smith et al. (2018) found similar results, with a 12% increase over 6 weeks. Both studies suggested that the high-intensity nature of HIIT was likely to be the key reason behind these adaptations. However, Smith et al. also noted that while HIIT enhances cardiovascular efficiency more effectively, CMIT appears to promote better endurance over time.

Taylor et al.'s (2020) review supports these findings but adds another consideration. While HIIT may lead to faster improvements in VO₂max, its long-term remains unclear. The review suggests that people who engage in CMIT experience more gradual improvements that are sustained over longer periods, potentially making it a better option for long-term cardiovascular health.

In summary, HIIT appears to be a highly effective tool for achieving rapid VO₂max improvements, but CMIT may offer more sustainable cardiovascular benefits in the long run. This suggests that the choice between HIIT and CMIT approaches could depend on the main goal of the training program, i.e. quick increase in fitness for a specific event, or long-term endurance improvement.

Tip

Key Tips for Integrating Information from Different Sources

- Focus on Themes, Not Sources: Organise your report by common themes (e.g., short-term vs long-term effects), rather than discussing each source in isolation.

- Be Critical: Don't just report what the studies say—analyse why the results might differ and what they mean in relation to your research question.

- Use In-Text Citations: Always cite the studies appropriately, but make sure the citations flow within your discussion of the themes or findings, not just as a list of summaries (we will be working on this soon).

By following this approach, you can integrate research from multiple sources into a cohesive, analytical report that demonstrates a deeper understanding of the topic.

Referencing

You now know how to find information and how to use it in your report, but even if you paraphrase information in your report, you still have to say where it came from. Learning how to reference properly is a skill that will assist you throughout your tertiary studies (and potentially in the workplace).

In this section of learning you will learn how to reference the sources you use in your report (in-text) using APA 7th edition referencing style. Note: we will cover post-text referencing when we have written the main discussion in our report. For now, just make sure you have copied the links to the full articles you have used and pasted these at the bottom of your assessment report document

In-text Referencing

During a written report, it should be easy for the reader to determine your own thoughts from the information you sourced from an article. Any information that hasn’t come from your own head needs to be referenced. An evidence-based report should be a mixture of your own thoughts and information taken from appropriate sources. This is where referencing comes in.

This is where you attribute a source to the information you used at the time of writing it. These references will be seen throughout your report. For in-text references we use an abbreviated form of the source. Typically, this involves giving just the lead author’s last name and the year of the publication. In some instances, it can involve using the article’s title instead.

In-text Referencing – The Rules

- If an article has only one author and the data of publication is given, reference using the author’s last surname and the date (in brackets) – e.g., Wilson (2008).

- If an article has two author’s names and the date of publication is given, reference using the surname of both authors (in the order they appear on the article) and the date (in brackets)- e.g., Wilson & Burrows (2008).

- If an article has more than two author’s names and the date of publication is given, reference using only the first author’s surname followed by the term “et al.” (which means “and colleagues”) and the date (in brackets) – e.g., Wilson et al. (2008).

- If no author’s name is given but the date of publication is, use the title of the article and the date (in brackets) – e.g., How to Reference (1998).

- If no date is given, use the initials (n.d.) to indicate “no date” – e.g. Wilson (n.d.), or How to Reference (n.d.)

Let’s Practice!

Each of the following cards will show a cropped image from a publication. Use the information above to type in the correct reference that you would use (in text) if you used information from this article in your assessment report.

Hints before you start the task:

- Use “&” instead of and between two authors names.

- There is a full-stop (.) after the words et al.

- There is a full-stop after the “d” in n.d.

- There is a space between the name (or title) and the date.

You may want to increase the zoom on your internet browser in order to see the information on the images a little clearer.

There are two ways to use in-text references:

- You can use the reference at the start of a new sentence:

A study by Wilson et al. (1998) found that regular cardiovascular training on machines at the gym produced the same cardiovascular benefits but failed to produce the same level of stress relief as performing cardio exercise in the outdoors.

The Effect of Exercise Location on Stress Relief (1998) suggested that those who performed their regular cardiovascular training on machines at the gym produced the same cardiovascular benefits, but failed to report the same level of stress relief as those who performed their cardio exercise in the outdoors.

Note: The date is bracketed after the authors name or article title. If no date the letters n.d. would be placed in the brackets. - You can use the reference at the end of a sentence in which the main ideas came from the source.

Participants who complete their cardiovascular training on machines at the gym may produce the same cardiovascular benefits as those who train outside, but they may not gain the stress relief benefits to the same degree as those who performed their cardio exercise in the outdoors (Wilson et al., 1998).

Those who perform their regular cardiovascular training on machines at the gym may produce the same cardiovascular benefits but fail to report the same level of stress relief as those who perform their cardio exercise in the outdoors (The Effect of Exercise Location on Stress Relief, 1998).

Note: The name, title and date are all placed within brackets with a comma separating them.

Time to make a start on task 2 of your assessment.

Task 2 is a written summary of your findings from the three articles you have chosen to discuss to help answer your research question. This is where you get to put your paraphrasing skills to the test. There is a specific structure you must follow when producing this written summary. Here is an overview of the task:

Task 2 – Written Summary of Findings

Provide a summary of information that will help answer your research question by analysing and integrating the evidence found within the three sources of information you have located. Your written summary should be written in your own words and be organized into the following sections:

- Introduction

- A summary of findings

- Reliability and limitations statement

- Conclusion

- Reference List

In this learning segment, we will go through each section of the written summary in turn. You will be given step-by step instructions on how to complete each section of the task and be shown an exemplar answer to help you understand what is required.

The remainder of your online learning and SDL for the week will be used to complete this task. Later in the week, your tutor will put aside some time in class to see how you are progressing.

Task 2 - Sections

Complete each section in your assessment document as you are introduced to them. The exemplar answers you will be shown relate to the research question:

“Does doing regular resistance training alone cause positive changes in cardiovascular health?”

The Introduction

Your introduction must include the following information:

- Your research question

- Some context (background) as to why you have chosen this topic (e.g., personal interest, involvement in the form of exercise, something you have wondered or wanted to try).

It should be approximately 100 words in length.

Exemplar answer:

My research question asks, “Does doing regular resistance training alone cause positive changes in cardiovascular health?”. I am interested in this topic because I have been doing resistance training for a few years now, but I don’t do any cardio. My heart rate definitely goes up during my weights workouts, so I would like to know if I can get any cardiovascular benefit from only doing resistance training, or whether I need to do cardio to get any positive effects. I am also interested to know if doing resistance training is beneficial for the cardiovascular system of older people, or whether it increases their risk of a cardiovascular event.

The exemplar answer above states the research question and gives clear reasoning for why the author has chosen to research this topic.

Your turn!

Complete the introduction to your Task 2 summary of findings now in your assessment report document. Remember to give this section a heading (Task 2) and each section you write a sub-heading, e.g., “Introduction”.

When you have finished your introduction, continue to the next section of learning (The Summary of Findings).

Summary of Findings

This section should be an integrated analysis of the evidence from your three chosen sources of information (i.e., what were the articles able to contribute to answering your research question, including any relevant facts and figures).

This is where you put your paraphrasing skills to the test! This answer should connect the evidence from the three sources of information (where possible) rather than simply discuss the findings of each in isolation.

Here is a reminder of the key steps you should take when completing this section:

Step 1 - Read and Understand Each Source

Start by thoroughly reading and understanding each of the three studies. Make a note of the main findings, methodologies, and any conclusions that are directly relevant to your research question.

The best way to start may be to write a short summary of each article including:

- The purpose of the study

- The methods used

- The main findings and conclusions.

Note: These summaries should not end up in your final assessment report, they should only be used to help you complete the paraphrasing you need to do in this section.

Here is an example of a brief article summary you could replicate for each of your articles:

Effects of short-term, medium-term and long-term resistance exercise training on cardiometabolic health outcomes in adults: systematic review with meta-analysis. Ashton et al (2018).

Article purpose: This review examined the effects of resistance training programs of different length on cardiovascular and metabolic function in non-athletic adults over 18 years of age (including older adults).

Methods: the authors reviewed 173 studies that looked at the effects of resistance training on measures of blood pressure, heart rate, blood glucose control and insulin levels.

Main findings: Resistance training appears to be effective for improving cardiometabolic health in healthy adults and also those with higher cardiometabolic risk. Resistance training improved both systolic and diastolic blood pressure (to almost the same degree as seen with cardio training). This was also seen in older population. Blood vessel (endothelial) function improved with resistance training (more ability to dilate). This was most noticeable in training programs that went for at least 7 weeks. Blood improvements included lowering of bad cholesterol, fasting blood sugar and insulin levels. They also suggested that people over 41 showed improved VO2 Max after regular resistance training.

Open a new word document and complete a short summary for each of your articles now. Once you have done this, move onto step 2 of the process.

Step 2 - Identify Common Themes

Look for any patterns, similarities, or differences from the brief summaries you have created. For example, do they all support the same conclusion? Do one or more have conflicting results? Think about what factors might explain these differences (e.g., different methodologies, sample sizes, or populations).

Step 3 - Group Related Information

Organise the information by theme or topic rather than by source. This could be based on the aspects of the physiological function being studied. For example, if all the studies related to heart function, they may all discuss the effect of exercise in blood pressure. You could then pool the findings about that one sub-topic in one sentence or paragraph.

Step 4 - Weave it together

Write a summary that weaves together findings from all the sources. You report should refer to each of the studies, but the focus should be on what the studies together say about the topic, not just reporting each study individually.

Step 5 - Highlight Agreements and Differences

If the studies largely agree on certain points, emphasise those shared conclusions. If they disagree, explain why the results might differ (different research methods, sample sizes, or populations). This helps to create a balanced and critical analysis of the evidence.

Below is an example answer. Note how this summary is organised by topic, rather than by article. It begins with findings on blood pressure, then moves to improved endothelial function and finally blood and VO2 max improvements. The first paragraph also shows an example of two articles not quite agreeing and provides a possible explanation for these differences.

This answer is also where you show your ability to use in-text referencing.

Exemplar:

From the research I have sourced, it appears that multiple positive benefits can be gained from doing regular resistance training (even if that’s all you do). A review by Ashton et al. (2018) reported a positive effect on both systolic and diastolic blood pressure in adults. They suggested that these benefits were about the same as you would get from doing aerobic exercise which was interesting. They also found that a positive effect on blood pressure was also seen in healthy older populations. While Evans et al. (2018) agreed that resistance training may be a suitable exercise choice for older populations (and even those with increased arterial stiffness), they only reported small improvements in blood pressure in the older populations in the studies they reviewed. They did note that resistance training didn’t increase blood pressure to dangerous levels during exercise and resulted in other favourable long-term benefits leading to a reduction in CVD risk. This review looked at the effect of resistance training on older populations with increased CVD risk, so it’s likely the intensities of the programs these subjects performed was lower than in the studies that used healthy populations. This might explain the less significant effect on blood pressure reported in this review. Evans et al. (2018) also talked about another meta-analysis that did show that resistance training leads to more significant reductions in blood pressure in older people. Younger populations in a Yu et al. (2016) experiment didn’t show any significant change in blood pressure from doing weight training (although they were healthy teens with normal blood pressure at the start of the trial). Interestingly, their sleeping systolic blood pressure did reduce after the 10-week resistance training program.

Other improvements from regular resistance training in adult populations included improved endothelial function (the cells that allow for the opening and closing of blood vessels). This effect was seen most in resistance programs that went beyond 7 weeks duration and the most noticeable effect was an increased ability to dilate blood vessels (which can reduce stress on the heart and within the CV system as a whole). This effect was also seen in adolescent populations (Ashton et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2016). The authors of both these studies agreed that this change came about because resistance training elevates blood flow for short periods of time under much higher pressure that sustained periods of moderate intensity exercise. This was thought to place more stress on endothelial cells, leading to their increased function.

Ashton et al (2018) also reported favourable changes to the blood from regular resistance training including reductions in bad cholesterol (LDL cholesterol), fasting blood sugar levels and insulin. Increased levels of these are all factors involved in increased CVD risk.

Finally, it appears that those over the age of 41 (along with older adults with elevated risk of CVD) can show significant increases in VO2 max from regular weight training (Ashton et al., 2018; Evans et al, 2018).

Your turn!

Complete your “summary of findings” section now in your assessment report document. Remember to give this sub-section e.g., “Summary of Findings”. This answer should be a minimum of 400 words.

When you have finished writing this section, continue to the next section of learning.

Reliability and limitations statement

In this short section, you will provide a brief discussion on the reliability of the information sources you have used for this report along with any limitations you believe relate to the findings you have collected (i.e., can the information you have found be related to any age, gender, or training experience?). You may also be able to find a limitations section within (or after) each article’s discussion section which may help you complete this answer. This is your own thoughts on the subject of article reliability, but you should still identify the article you are talking about by using in-text referencing.

Here is an example answer:

I believe all three articles used were good sources. They all came from well-known peer-reviewed journals meaning they would have had checks to ensure they are a high-quality source. There were a few limitations to do with the articles. The Yu et al. (2016) article had a fairly small number of subjects (38), and they were all fit and active students involved in other sports. This means the other sports may have contributed to the results making it hard to know if the results were due to the resistance training. The Ashton et al. (2018) article said that the subjects of the trials in their systematic review had far more males than females which could make it hard to relate the results to women with confidence. The Evans et al. (2018) article suggested that there was “considerable variation” in the volume and intensity of the exercise programs across the trials in their report, which could make it difficult to know which of the training programs were most effective.

Your turn!

Complete your “Reliability and Limitations” section now in your assessment report document. Remember to give this sub-section e.g., “Reliability and Limitations”. This answer only needs to be approximately 100 words.

When you have finished writing this section, continue to the next section of learning.

Conclusion

In this section, you attempt to answer your research question using the evidence you have collected. As part of this answer, you might suggest who could benefit from the information you have found. Conclusions are not sections in which you introduce new information, they are simply a place to weigh up the information you have found in your articles and give your informed opinion on your best answer to the question you have asked.

An example answer is given below:

The evidence provided by my three research sources shows that there are some good cardiovascular benefits you can get from just doing resistance training. The main one seems to be better endothelial function (dilation) of the blood vessels which can reduce stress on the heart. This effect was seen in all population groups from adolescent through to older age. Adult populations also seem to be able to reduce their resting blood pressure. This may also be true for older populations and even those with higher risk of CVD seem to be able to participate in resistance training (while not making their blood pressure any worse). Those over the age of 41 and older populations with elevated CVD risk appear to be able to get decent increases in VO2 Max from weight training with a low chance of having cardiovascular issues during the training. This could be a great outcome if the ability to perform other forms of exercise is limited due to a lack of mobility. Finally, blood markers that relate to CVD can be reduced in adults through regular resistance training. These improvements include reductions in bad cholesterol, fasting blood sugar and insulin levels. Overall, it would seem that resistance training is a safe and effective exercise option to improve these measures of cardiovascular health for teenagers through to elderly.

Your turn!

Complete your “Conclusion” section now in your assessment report document. Remember to give this sub-section e.g., “Conclusion”. This answer only needs to be approximately 150 words.

When you have finished writing this section, continue to the final section of learning related to this task.

Reference List

Now that you have completed your summary of findings, the final sub-task you need to complete for task 2 is your post-text reference list. While the use of an author’s name (or article title) and date is enough for in-text referencing, when writing a research-based report, you also need to provide a full reference for each external source of information used. A full post-text reference needs to include the following:

- All authors surnames and Initials (if available)

- The date of publication (if available)

- The title of the article

- The publisher or website domain of the article

- A website link to where the article was retrieved from

This used to be a time intensive process. Luckily online citation tools have been developed to make this process far simpler and more efficient.

Now that you have used some external sources in your report, it is a good time to learn how to use one of these free citation generators to produce your post text reference list. All you need is the URL link you have copied for each of the external sources you used.

This short video shows you how to produce your post-text reference list using a free citation generator called Scribbr. Use the information in the video to follow along and produce your own reference list (for the articles you have used in your report). Place this list of sources under your conclusion section with a sub-title “References”.

Video Title: Post text referencing with a citation generator

Watch Time: 13:31

Video Summary: This short video shows you how to produce your post-text reference list using a free citation generator called Scribbr

Post Watch Task: Use the information in the video to follow along and produce your own reference list (for the articles you have used in your report). Place this list of sources under your conclusion section with a sub-title “References”.

Source: YouTube (Authors own)

Assessment 2 brings together all the learning we have covered over the last couple of weeks. It is an open book written & practical assessment that will be completed in 2 parts. The assessment will be completed over a one-week period. All class, online and SDL study time for this subject from today until the end of next week will be devoted to completing this assessment.

The two tasks that make up this assessment are outlined below:

- Task 1 - (Written answers): Identify and describe appropriate rehabilitation or injury prevention strategies for a given case study client.

- Task 2 – (Written answers and practical demonstration): Apply common rehabilitation or injury rehabilitation strategies to target musculoskeletal issues in a case study client.

Case Study Clients

The entire assessment revolves around identifying, explaining and demonstrating appropriate injury rehabilitation or prevention techniques for a case study client and the musculoskeletal issues they present with. You tutor will allocate you one of 6 case study clients that you will base your assessment answers on.