In the final topic of learning content for Module 4 we will be looking very closely at the structure of animal bodies. This will provide a basic level of scientific knowledge to link with the content in Module 5 where we will look at common health issues of companion animals and how to treat them.

An animal body plan is the basic structure and pattern of how their internal organs and tissues are organised. Animal body plans are also HOW animals are classified under the Linnaean Taxonomy that we started this module with. In a way we are completing a full circle of learning, where we started with taxonomy, then moved onto specific physical features of species and breeds and will finish up with body plans.

The key parts of a body plan are:

- Symmetry

- Organisation of tissues and body cavities

Symmetry

If something is symmetrical it means that it if you drew a line through it each half would be a mirror-image of each other. Animals are either radially symmetrical or bilaterally symmetrical. Radial symmetry is found in animals like jellyfish or starfish. In the starfish image below, if you were to extend any of the blue lines fully across the animal, the starfish halves defined by any the lines would be mirror-images of each other. You could prove this by holding a small hand mirror against the screen of your device, cutting the starfish in half along the blue lines.

Bilateral symmetry is the most common type of symmetry in the Animal Kingdom. In the image of the fly below the blue line is dividing it along the sagittal plane, which is the only plane where there are symmetrical sides.

Animals can also be divided along the transverse or frontal places, but these are not symmetrical. See the image below of a human figure which shows all three planes.

All of the animals discussed in this programme have bilateral symmetry.

Features

Animals with bilateral symmetry have the following features:

- Have the ability to move under their own power (for example, via legs or wings).

- Have feeding, sensory and processing organs at the anterior (front) of their bodies (contained within the ‘head’).

- Have a ‘tail’ end of the body (posterior).

- Have dorsal (the back) and ventral (the front) sides of the body.

- Move towards items in their environment with the anterior end of the body leading.

Note

The concept of symmetry needs to be understood as something approximate rather than exact. For example, humans have external symmetry, but not internal symmetry. Your heart is on your left side only and your liver is mostly on your right side. One lung is bigger than the other.

This is the same for our companion animals as well.

All vertebrates, and therefore all animals in the Chordata phylum of Linnaean taxonomy, have bilateral symmetry. They also have the same basic body plan.

What is a Body Plan?

When scientists use the term ‘body plan’ they are often referring to the embryonic form of the animal. This is the basic first form of an animal inside its mother (dogs, cats, rabbits, rodents), or within an egg (birds). Adult animals that do not look similar to each other can have the same body plan: a parrot and a terrier do not look much like each other, yet early on in their life cycle a parrot embryo and a terrier embryo would be difficult to tell apart. Animals in the Chordata phylum have the following when they are in the embryo stage of their lifecycle:

- a notochord (the spine of the embryo, which becomes the rubber-like discs between the bones in the spine in the adult form)

- pharyngeal slits (which in fish turn into gills for filtering water, but develop into other body parts in land-based animals)

- a hollow dorsal nerve cord (which becomes the spinal cord and brain)

- an endostyle (which turns into the thyroid gland)

- a postanal tail (which becomes a tail in dogs, cats, rabbits and rodents, but is less important for birds and humans)

You can see the similarities between embryos in the image below, especially on the left-hand side.

How and why embryos go on to develop into parrots, terriers or any other animal is not part of the content for this programme. However, a basic understanding of body plans is useful background for understanding the health, nutritional needs and medical treatment options for companion animals. You may be involved in conversations with vets and vet nurses where they will use scientific terms, and knowledge of these terms will help you understand and participate more meaningfully in these types of conversation.

Let’s take a moment to check that you have understood these new terms by completing the activity below.

Activity

As an embryo develops different types of tissues are forming that will eventually become important structures/organs of the animal body. ‘Tissue’ means a group of cells in the body that work together to perform a specific function. The four types of tissue that we need to know are:

- Connective

- Epithelial

- Muscle

- Nervous

Connective Tissue

These kinds of tissue provide structure, support and protection for other tissues of the body. Some types of connective tissue also provide storage for fat cells or deliver nutrients and oxygen to cells and remove waste form them (blood cells).

The cells in connective tissue make fibres made of different types of protein. Collagen fibres provide strength, stopping the surrounding tissues from being stretched or torn. Elastin fibres help surrounding tissues to stretch and then return to the original shape. Examples include:

- Cartilage (mostly collagen fibres) found in joints between bones, ears, ends of noses, bird beaks, parts of the rib cage and separating the spinal bones.

- Bone (a mix of collagen and elastin fibres) found in the skeleton.

- Blood (plasma, red and white cells).

Epithelial Tissue

This kind of tissue is found on the outside of structures and organs or their inner linings and also forms the outer layer of the body itself. Its purpose is protection. Examples include:

- Skin

- Stomach lining (or the acid in stomach would burn through the other types of tissue)

- Inside intestines (to prevent waste from entering the body)

- The outer surface of blood vessels (blood is mostly liquid and needs to be contained)

Muscle Tissue

Muscle tissue helps animals to move. Movement could be things like running or jumping, but it could also be things like pumping or contracting and expanding (hearts and lungs). Muscles also provide protection for internal organs, stability for bones and help bodies release heat.

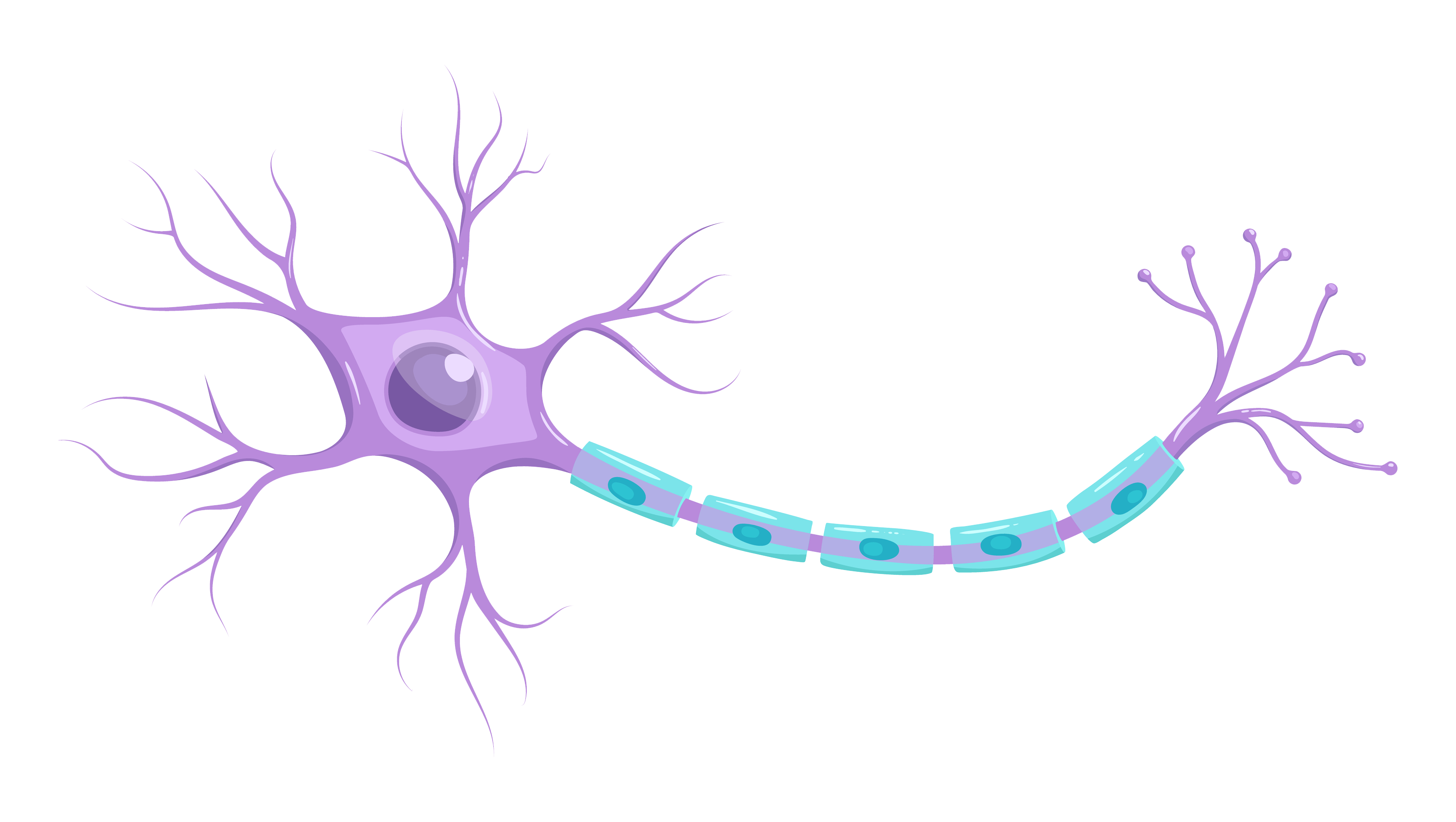

Nervous Tissue

Nervous tissue helps transmit information to and from the brain and other areas of the body via electrical impulses. The main type of nervous tissue is the neuron. In animals and birds the sciatic nerve, the longest nerve, stretches from the brain right down to the feet or claws.

Activity

Take a moment to review what we have just covered about Animal Primary Tissues by completing this multi-choice activity. Use the arrows to move through the questions.

Tissue differences in Companion Animals

Remember that our companion animals all have the same basic body plan. This means that in general the way their internal organs are laid out will all have a similar arrangement, and they will all have similar internal organs. There are some important differences: some of our companion animals have adaptions to the basic body plan that are related to helping them survive in the wild. We don’t need to cover all of the details of these adaptions in this programme although you will definitely study them if you decide to have a vet career. Here’s some useful points to note:

- Cats have more muscle and less cartilage in their spines which makes them flexible.

- Rabbits have an extremely light bone structure which gives them speed and agility to escape from predators.

- Dogs have a high concentration of nerves in their noses to give them their excellent sense of smell.

- Coat colours, types and patterns in our 4-legged companion animals all relate to cells that are found in the epithelial tissues that provide physical features that can help keep them warm or cool depending on the climate.

- Birds have hollow bones to help them fly.

- Psittacine birds have nerve endings in their beaks which helps them identify and manipulate food and also helps the beak function as a kind of third limb.

- A combination of nerve, bone and cartilage in passerine bird legs helps them sleep without losing grip on their perches.

- Rat and mice whiskers have lots of nerve endings to help them navigate in the dark.

- Mice don’t have a collarbone which enables them to squeeze into tight places.

- Cartilage in rabbit ears helps with keeping the ears upright enough to hear for predators without being inflexible like bone is.

- Some dog breeds have very strong bones to be able to hunt animals that are much bigger than themselves – this reduces the risk of them dying while bringing the animal down.

Bioenergetics is the study of the balance of: energy generated by eating food; energy used to maintain the body processes that keep the animal alive; and energy lost due to things like heat and body waste.

You will notice that a lot of energy is lost as heat. This is important because releasing AND maintaining body heat is important for all of our companion animals.

All of our companion animals discussed in this programme are endothermic. In plain language we can use the word ‘warm-blooded’. The bodies of warm-blooded animals can automatically self-regulate between retaining enough heat to keep the body running versus losing enough heat so that the body is not damaged. This process is called thermoregulation (heat control) and is an example of homeostasis – which just means keeping something in a state of balance.

Fat, fur and feathers (epithelial tissues) play an important role here:

- They help trap enough heat to keep the animal warm,

- They allow enough heat to be released to ensure that the animal doesn’t overheat which would cause internal body damage.

Breed types that are ‘hairless’ need human attention to keep the balance between maintaining and releasing body heat, especially in colder climates.

The science of animal bioenergetics allows animal nutritionists to calculate how much food each type of animal needs at different life stages and levels of activity. Getting the right amount of food is key to keeping animals happy and healthy.

Animal nutritionists will work out how much energy the animal uses over a specific time to find its base metabolic rate or BMR. This is measured in either calories or kilojoules, the same as for humans.

It may surprise you that smaller animals need more food and that larger animals need less food than body size alone would suggest. This is because of energy loss through heat (look at the diagram above again). To help understand this we also need to talk about surface area to mass. Let’s take a mouse and a Great Dane dog. The proportion for each animal of inside (body organs, etc.) and outside (skin surface) is like this:

- A mouse has more skin on the outside compared to the amount of body tissue on the inside.

- A dog has more body tissue on the inside than it does compared to the skin on the outside.

Therefore, a mouse will lose more heat because it has a greater area of skin to body mass and will need to eat more to make up for energy lost as heat. A dog will retain more energy than a mouse because it loses less heat in the process of converting food to energy. Mice can die easily from cold, while dogs need to reduce their body heat by doing things like panting.

Other things that must be taken into account include how active the animal is: which includes its natural behaviors, the type of food it gets its energy from, how much exercise it gets and how healthy or old it is. Usually animal nutritionists will work out an average BMR for each animal and recommend a daily food intake based on that. Caregivers of animals would then need to make adjustments for individual animals based on activity, age and health.

In the wild some animals will go into a state called torpor, where the metabolic rate of the animal slows down. This lowers both body temperature and level of activity and its purpose is to help animals survive extreme hot or cold weather or times when food is not easily available. Some animals do this only over winter (hibernation in bears for example), but other animals, especially those that live in hot climates, may go into torpor on a daily basis.

Pet rats and mice may go into torpor if their living conditions are cold, or if they are not getting enough food to meet their BMR. If this happens, the best thing you can do is to provide them with warmer living conditions and/or more food. Remember, torpor is for survival, and can therefore cause your animal stress if it happens unnecessarily.

Activity

Review the vocabulary we have just covered by dragging the words to match their explanations.

We’ve covered a lot of content which will help you in your future career in the animal care industry. The key takeaways from this module can easily be summed up as follows:

- The form of animal (its physical body) relates directly to how it lives and keeps itself alive (functions).

- Breeding by humans has caused changes to some of the forms and functions: either for the pleasure of appearance or for usefulness to humans.

- If we understand why an animal looks and acts the way it does, we can take better care of it when we keep it as a companion.

Another way of summarising is shown in the following activity.

Activity

Click on the Turn button to display an explanation for each concept. Use the arrow keys to navigate between slides.

Assessment Tips

You are now ready to start on the assessment for this module: 04A1. This assessment has a different layout than previous assessments. Instead of case studies and short answer questions, the main part of the assessment requires you to make information leaflets in a style suitable for giving to new owners of pets. The purpose of the information leaflets is to help owners understand their new family members and provide them with tips on how to care for them. A good grasp of the three bullet points/flow chart in the summary above will help you to write an informative leaflet and demonstrate how much knowledge you have taken in about animal form and function.

As with all of the assessments in this programme, you should write this in your own words to demonstrate how well you have understood and remembered the learning content.

The case study below will help you understand what is required in the assessment.

Case Study

Information Pack Leaflet for a Pure-bred Peruvian Guinea Pig

Emily has been asked to research and type up information about a pure-breed female Guinea pig that they have available for adoption at the SPCA. She’s made it sound as interesting and personable as possible so that Ellie (the adoption name that Emily has given the Guinea pig) and her new owners bond well with each other. She runs it past her supervisor first before putting the final copy in Ellie’s adoption folder. Her supervisor is very pleased with how well Emily has put the information together.