There are a variety of models of human development that we can use to think about the different aspects of our own life or the development of a young person we are working with. These conceptual frameworks can help us think about the development of a young person as a ‘whole’ human being.

In this topic we will focus on three of the models commonly used in youth development and healthcare contexts in Aotearoa:

- Te Whare Tapa Whā

- Te Wheke

- The Circle of Courage

The first two models were developed by Māori academics and reflect a Māori perspective on health and well-being. Te Wheke builds on the concept of Te Whare Tapa Whā. The third model was originally developed to include North American indigenous philosophy but has been adapted for use in Aotearoa by placing it in a Māori context. The Circle of Courage can be adapted for any youth work development.

For youth work in a Māori context, this means using models that are ground in the three fundamental connections of whānau, whakapapa and whenua – as you will notice with the three models presented here. The metaphor often used is of weaving the threads of the relationships around young people with their whanau, whakapapa and whenua. It is important to always address these fundamentals when working with young people in Aotearoa.

Introducing Positive Youth Development in Aotearoa

Positive Youth Development in Aotearoa (PYDA) is a framework for youth development. It provides models and tools to implement the Government’s Youth Development Strategy Aotearoa (YDSA). The main outcomes for the PYDA framework are to develop the whole person and to develop connected communities. The three key approaches of PYDA, which you will learn more about later in your studies, are strength-based approaches, forming respectful relationships, and building ownership and empowerment.

For youth work in a Māori context, this means using models that are ground in the three fundamental connections of whānau, whakapapa and whenua – as you will notice with the three models presented here. The metaphor often used is of weaving the threads of the relationships around young people with their whanau, whakapapa and whenua. It is important to always address these fundamentals when working with young people in Aotearoa.

Te Whare Tapa Whā is a holistic model of health and well-being that was developed by Sir Mason Durie in 19841. The model depicts the overall health of a person as a wharenui (meeting house) with four walls representing four dimensions of the person’s well-being. If any one of these walls is missing, weakened or damaged, the person’s health suffers and they will become unwell unless that wall is restored.

- Taha Tinana is the person’s physical well-being. It includes physical fitness, good nutrition, healthy sleeping habits, and being free from illness.

- Taha Hinengaro is the person’s mental health and emotional well-being. It includes the person’s thoughts, feelings and attitudes, as well as how they react to challenging situations.

- Taha Wairua is the person’s spiritual well-being, which could be a person’s sense of their mauri (life force) or an expression of their religious faith. Taha wairua incorporates a person’s sense of where they have come from, where they are going and their connection to the universe.

- Taha Whānau refers to the person’s family and social bonds. Taha whānau is about the quality and quantity of relationships in the person’s life – who they care for and who they can count on for support during life’s challenges.

A later variation of this model includes a fifth dimension: Whenua. This is the person’s connection to the land under the wharenui and is the foundation that the four walls rest on. In this model, Whenua can refer to a person’s association with their natural environment – all the plants, animals, air, water and soil – as well as their connection to their tūpuna (ancestors). It’s also about a sense of belonging to the place you’re in, and the comfort that brings.

-

Taha Tinana

Physical wellbeing

-

Taha Hinengaro

Mental and emotional wellbeing

-

Taha Wairua

Spiritual wellbeing

-

Taha Whānau

Family and social wellbeing

-

Whenua

Connection to land and roots

The idea behind Te Whare Tapa Whā is that when someone is having trouble with one of these dimensions of their well-being, they can draw on the strength of the other three dimensions while they work on the area where they are feeling under pressure. This model presents these five dimensions as being equally important to the overall health and well-being of the individual.

Think back to a time when you were struggling or feeling challenged in one of these dimensions. Do you remember how you recovered from this difficult time? Do you feel like you drew support from one or more of the other dimensions to help you overcome your difficulties? Make some notes describing your experiences.

Explore further

This webpage explains how Te Whare Tapa Whā underpins Mental Health Awareness Week2.

This resource is focused on how to apply the concept to personal mental health. There are activity ideas to do with groups via links at the bottom of the page.

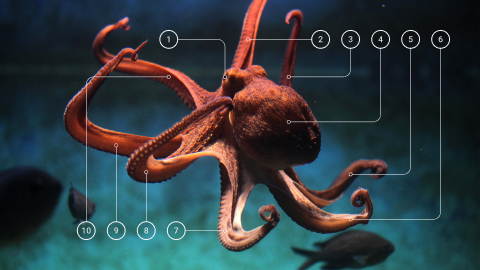

Te Wheke (octopus) is a model developed by Rose Pere in 1991 for considering family health through a Māori lens3. The head or body of the octopus represents te whānau (the family), while its eyes represent wairoa, which is total well-being for the family as a whole and any individual within that whānau unit. The eight arms or tentacles of the octopus represent different but interconnected dimensions of health.

- Wairoa (total well-being)

- Wairuatanga is the person’s spirituality

- Hinengaro is the person’s mind. This is about their cognitive development

- Te Whānau (the family)

- Taha tinana is the person’s physical wellbeing

- Whanaungatanga is about the relationships between the family and members of their extended family

- Mauri is the life force in people and objects

- Mana ake is the unique identity of individuals and the family

- Hā a koro ma, a kui ma is the breath of life from one’s forbearers or the person’s connection to their ancestors

- Whatumanawa is the open and healthy expression of emotion

According to this model, each of the eight arms can be extended to find and gather what is needed for the whole whānau to survive. Sometimes the arms of an octopus will become intertwined with each other, which represents the way these eight dimensions of well-being are interconnected and do not always have clear boundaries between them.

Think about how the model of Te Wheke could be used to view the overall well-being of a family unit. Can you think of other ways in which these eight dimensions of family health could be compared to the arms of an octopus?

The Circle of Courage is another model of youth development, which was developed in 1990 by Larry Brendtro, Martin Brokenleg and Steve Van Bockern at Augustana University in South Dakota4. It is based on the four principles of belonging, mastery, independence and generosity, which all children strive for and require as part of their growth. These four principles are depicted as points around a medicine wheel, which is a symbol occasionally used to convey North American indigenous concepts.

This model of the Circle of Courage has been modified and used all over the world. Here in Aotearoa, the four principles have been adapted to fit a Māori worldview as follows:

Similar to the way that belonging to a community or tribe is a significant part of indigenous North American cultures, a person’s place in their whānau or hapū is a central aspect of Te Ao Māori (Māori worldview). These familial connections and social relationships help provide a network of support and respect for young people.

Being able to prove one’s abilities and achievements is as important for young people as it is for adults. Having the ability – and the opportunity – to learn from those who are more experienced, overcome challenges and attain mastery of skills that are valued by the young person is a crucial part of their development.

Part of the transition to adulthood is having more autonomy, as well as the discipline and responsibility necessary for success. This principle is about giving the young person the opportunity to make their own decisions so they might develop the maturity to own their decisions.

This principle focuses on nurturing generosity as an important personal quality. A young person who demonstrates altruism and unselfishness cannot help but make positive contributions to the lives of those around them.

If you would like to see an image of this adapted model, you can view an example developed by Te Ora Hou Ōtautahi

Think about how you could apply the Circle of Courage to how you work with young people.

Make some notes for each of the four principles.

You might feel that some of these principles are more straightforward to apply in your workplace than others – for instance, nurturing Pukengatanga might be an obvious part of your role but you might need to think a bit harder about how you model or encourage Atawhai. You could write about how you think you currently incorporate this principle in the way you deal with young people currently, or describe how you could introduce the principle into your work practice.

Compare the three models of youth development that you have just learned about and answer the following questions.

- What is a theme, principle or concept that all three of these models have in common?

- In your opinion, is there an important idea that one of the models focuses on that is not covered by the other models? What is this idea and which model do you think addresses it the best?

Are you confident you have a good understanding of the three models of youth development we have covered in this topic?

- Which of these models do you find the most compelling or interesting?

- Make a list of some of the ways that having a broad understanding of models of youth development, or being really familiar with one model in particular, could help you within your context and the work you do with young people.

- Are there any models of youth development you know that should be included in this topic? You may be familiar with another model that is cited or used in your workplace.

You are now ready to complete Task 2 of Assessment 1.1.