Design 'elements' are fundamental to all design. Designers use the elements to create images, convey mood, draw the eye in a particular direction, or evoke emotions. These elements include point, line, shape, texture, colour, space, pattern and many more.

The information below will cover 5 of these elements.

Point

A point is the simplest design element--typically a dot or a small object marking position. A single point can focus attention on a position, such as a location on a map. When multiple points are used, the brain creates connections between the points, forming lines or shapes.

Line

A line can be more than a continuous thin mark. A better definition for a 'line' is 'anything that connects 2 points'.

A line does not necessarily need to be continuous or solid, it can be anything that the eye can follow between points:

- several small objects arranged to form a line

- a ‘line of text’ is a line

- a small, consistent gap between 2 shapes could even form a line.

Lines are a powerful design element that can be used effectively for many different purposes. For example, lines can:

- direct a reader’s eye

- connect information

- separate information

- highlight information

- define forms (shapes or 3-dimensional objects)

- create a pattern or rhythm when repeated

- imply movement

- suggest moods and emotions

- create a sense of perspective/depth

- represent data (e.g. barcodes, graph lines).

Qualities of line

Lines don’t have to be consistent, continuous or straight. They can be applied in various formats to express different concepts, emotions, styles etc. For example:

- jagged, straight lines could be used to suggest energy, excitement, violence etc.

- smooth, flowing curves create a soft, gently flowing, tranquil feeling

- a dashed line might suggest that something should be cut out

- curvy lines have an organic, natural association

- fine, straight lines might suggest precision.

Always consider the possible associations when using lines, so you don’t confuse or mix emotions. For example, using jagged or vertical lines in the logo for an airline might, on a subliminal level, suggest turbulence and danger.

Shape

A shape does not necessarily have to be filled with a solid colour or defined by an outline. The distinct form of a shape can be defined in a variety of ways.

Different categories of shapes include:

- geometric: triangles, rectangles, circles, polygons etc.

- natural/realistic: closely representing any natural or manufactured forms

- stylised: based on natural or geometric forms but with modified attributes

- random: without any conscious reference to any natural or geometric forms.

Shape can be used as an influential element in design. It can:

- attract attention to your design or the elements within it

- make a design more interesting

- symbolise an idea

- tie elements together in a design

- guide the eye around a layout.

Information that surrounds us is almost always presented to us in rectangles as this is the most practical and economical shape to work with. Books, newspapers, magazines, television, computer screens, mobile devices, photos, billboards, calendars, menus, letters and envelopes are all usually a rectangular format. This can make rectangular-shaped information look rather monotonous.

If you are working within a rectangular format, think about the shapes of elements in your design. What can you do to make the content more attractive or usable?

Tips for incorporating shape into your design

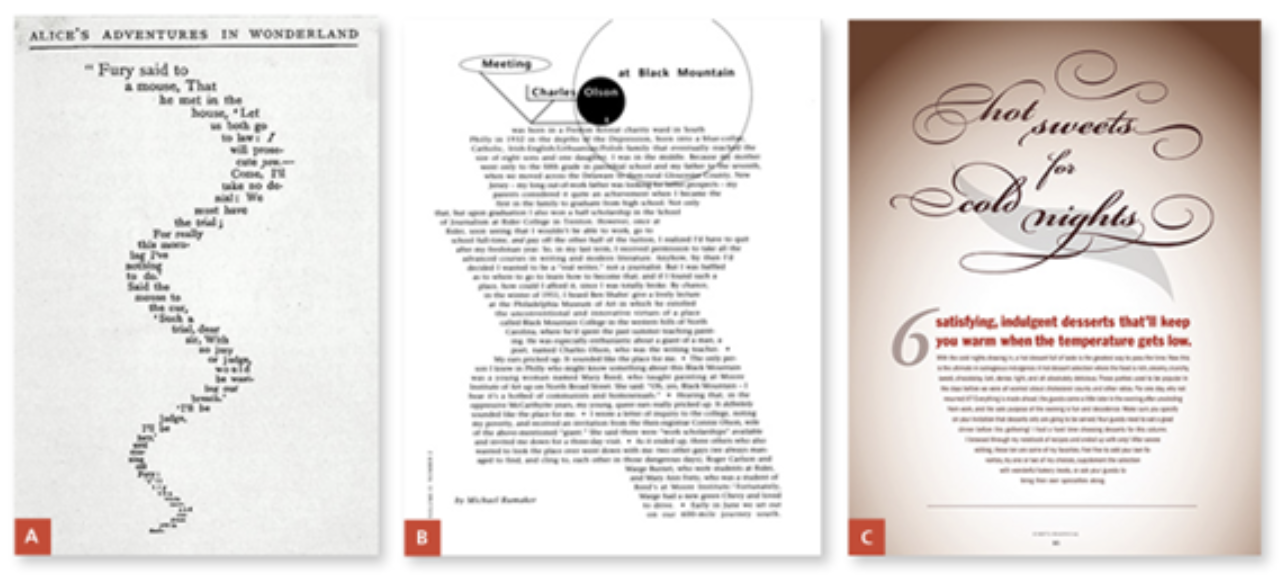

- Try flowing-text within a text box that is an interesting or relevant shape to the article. The use of the justify text alignment option will help the text to fill the shape precisely without a ragged edge. Keep to simple shapes to avoid text breaking up.

- Liven up a boring rectangular block of text by placing graphics inside or around the edges of the text frame with text wrapping applied to them.

- Create an attractive shaped negative space within rectangular media with the use of shaped borders.

- Clear-cut a subject in a photograph so that it is isolated from the photo’s rectangular background.

- Place images within interestingly shaped content boxes. Cropping a photo into a long, thin rectangular shape can also be an exciting variation to a standard (3:2 or 4:3) photograph format.

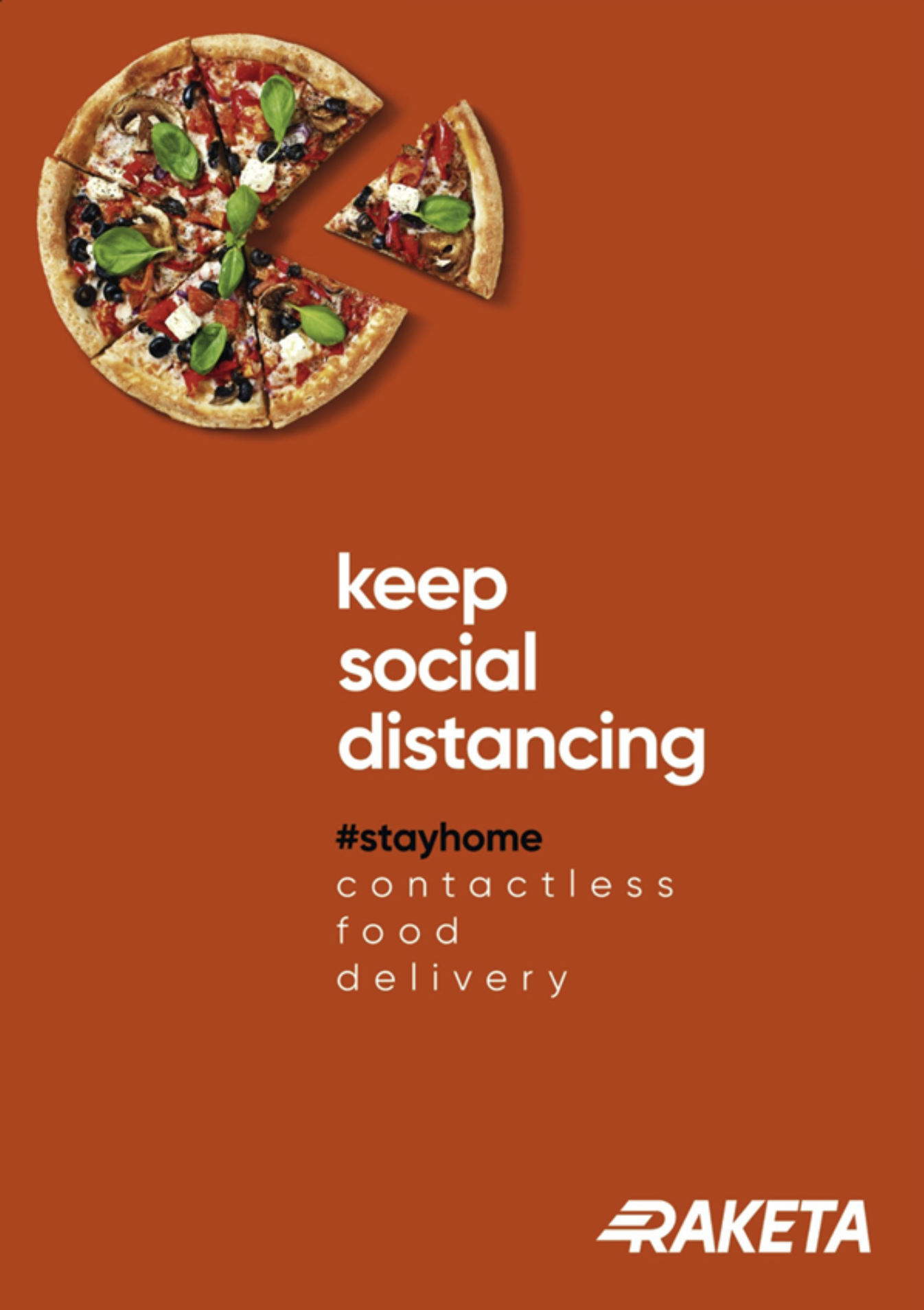

- Try dividing an image geometrically into segments and then move the pieces apart slightly or apply different effects to distinguish each segment.

- Using careful composition and arrangement of the subject when taking photos can make photos much more powerful. The eye responds particularly well to strong geometric relationships between objects in a photograph, even when they may not be so obvious.

Space

A common error when laying out a document is thinking that every space needs to be filled. You should be aiming to create space, not to fill it. A common phrase to sum this up is ‘less is more’.

Space is a vital element required to separate information in a layout. People can scan, absorb and process information more efficiently when it is presented clearly in separate chunks.

If the information is surrounded by clutter, the brain has to work harder to filter out the excess information to find out what is important.

A reader will be drawn subconsciously toward those elements in a layout that have plenty of space surrounding them.

The term ‘space’ does not necessarily mean an empty area of white space. It may be filled with a colour or a simple background texture.

If you give someone a page of text that fills an entire sheet of paper from edge to edge, they may agonise over having to read it. However, consider if you presented the same amount of text laid out over 2 pages. This would allow for generous margins, more space between lines of text, and allow room for pictures. The reader will find it easier to read the 2 pages than the single page with the same amount of text.

Texture

All surfaces have a specific visual appearance or a tactile quality. You are surrounded by many different textures in your everyday life.

Look at the following examples of textures that can be used throughout your designs.

- Natural: Surfaces that occur naturally (e.g. tree bark, leaves, rock, water ripples, sand, fingerprints, skin, fur).

- Man-made: Manufactured surfaces (e.g. fabric, paper, printed text, bricks, metal, plastic, tiles, glass).

- Imperfections: Added (random) textures (e.g. scratches, tears, cracks, rust, splotches, stains, effects of weather).

Many of these textures are 'tactile' (meaning that you can touch and feel them). Adding visual textures to elements in your designs adds a certain quality that will often make your work a lot more interesting than boring, flat, plain areas of colour.

The principles of design are rules a designer follows to create a compelling and attractive composition. Fundamental design principles can include emphasis, balance, alignment, contrast, repetition, proportion, movement and white space.

We will cover 9 of these principles in more depth.

Contrast

Contrast relates to the amount of visual difference between elements in a composition.

Too little contrast in a design can look dull and uninviting, and individual elements may be harder to distinguish.

Too much contrast can create a harsh, unnatural or chaotic appearance.

Aim to create an adequate amount of contrast to complement the brief’s requirements and each element in a design.

Text in a design usually requires strong contrast to ensure legibility. Be particularly careful when placing text on top of colour (mentioned in the Colour Theory topic above), texture or a background image, as it may require special treatment to provide adequate contrast. Try using stroked outlines, drop shadows or glows.

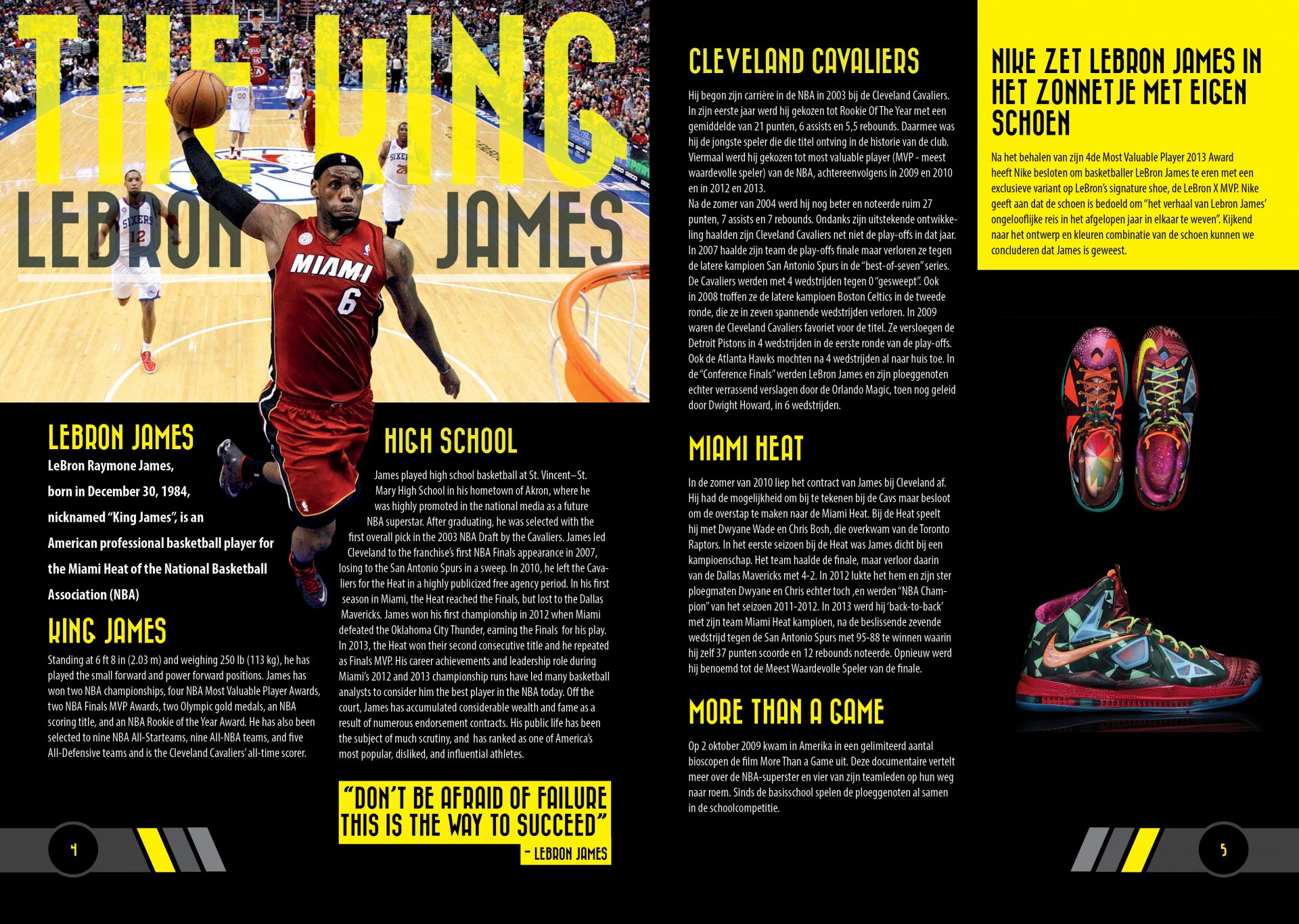

Headings and subheadings should have a stronger contrast than the body text to help structure a document.

You can use strong contrast selectively to emphasise or focus a viewer’s eye towards a particular element that you want to be noticed first.

Tonal contrast

Tonal contrast is the darkness or lightness of an area. Sharp changes between dark and light colours create dramatic contrast, while a transition using intermediate tones creates softness with less contrast.

Tones can be digitally manipulated in Adobe Photoshop with adjustment features such as Brightness/Contrast, Levels or Curves within an image.

When you are placing text over an image, consider the tone of the overall area. You may need to use white or light coloured text if the tonal area of the image is too dark.

Colour contrast

Careful application of colour can improve contrast. Remember, colours opposite each other on the colour wheel are complementary and have the most contrast.

(Consider revisiting the Colour Theory topic for advice on selecting colours.)

Size contrast

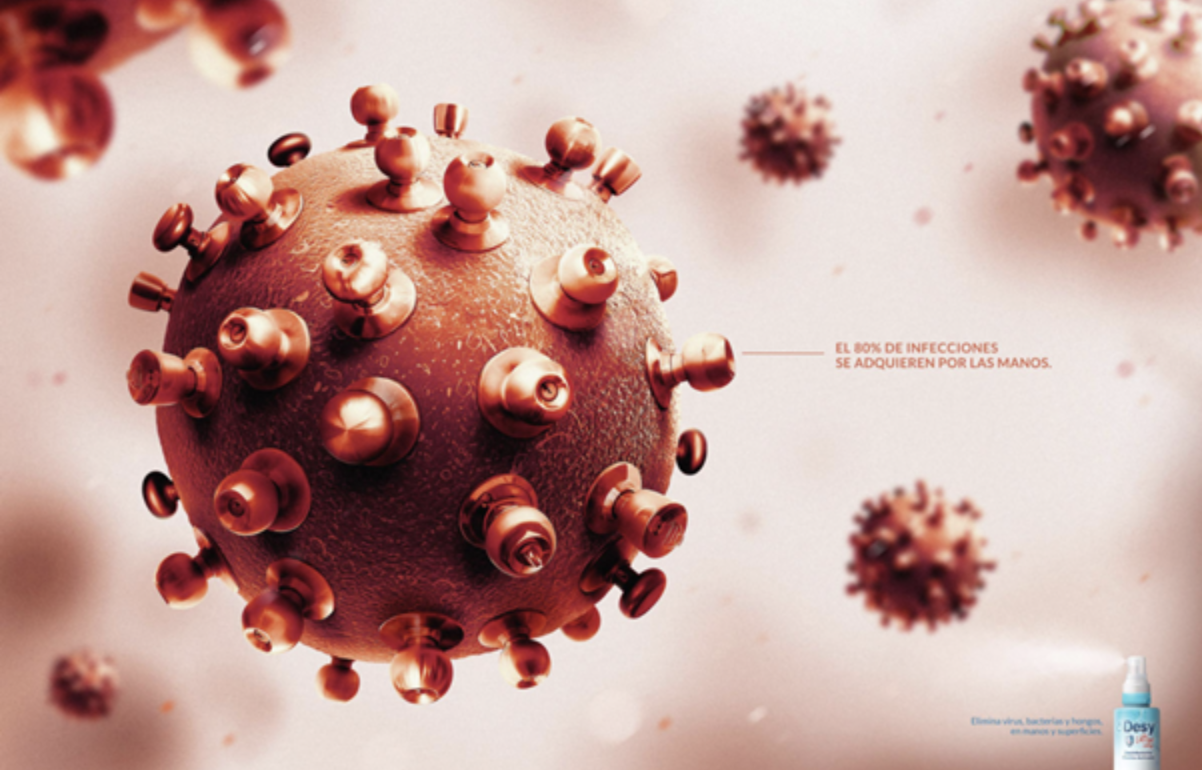

Differences in size create higher contrast between elements. This applies to the size and weight of text, the size of images and objects and the weight of strokes.

Style contrast

Use styles of typography, illustration and photography to emphasise contrast. Consider juxtaposing elements, highlighting their differences.

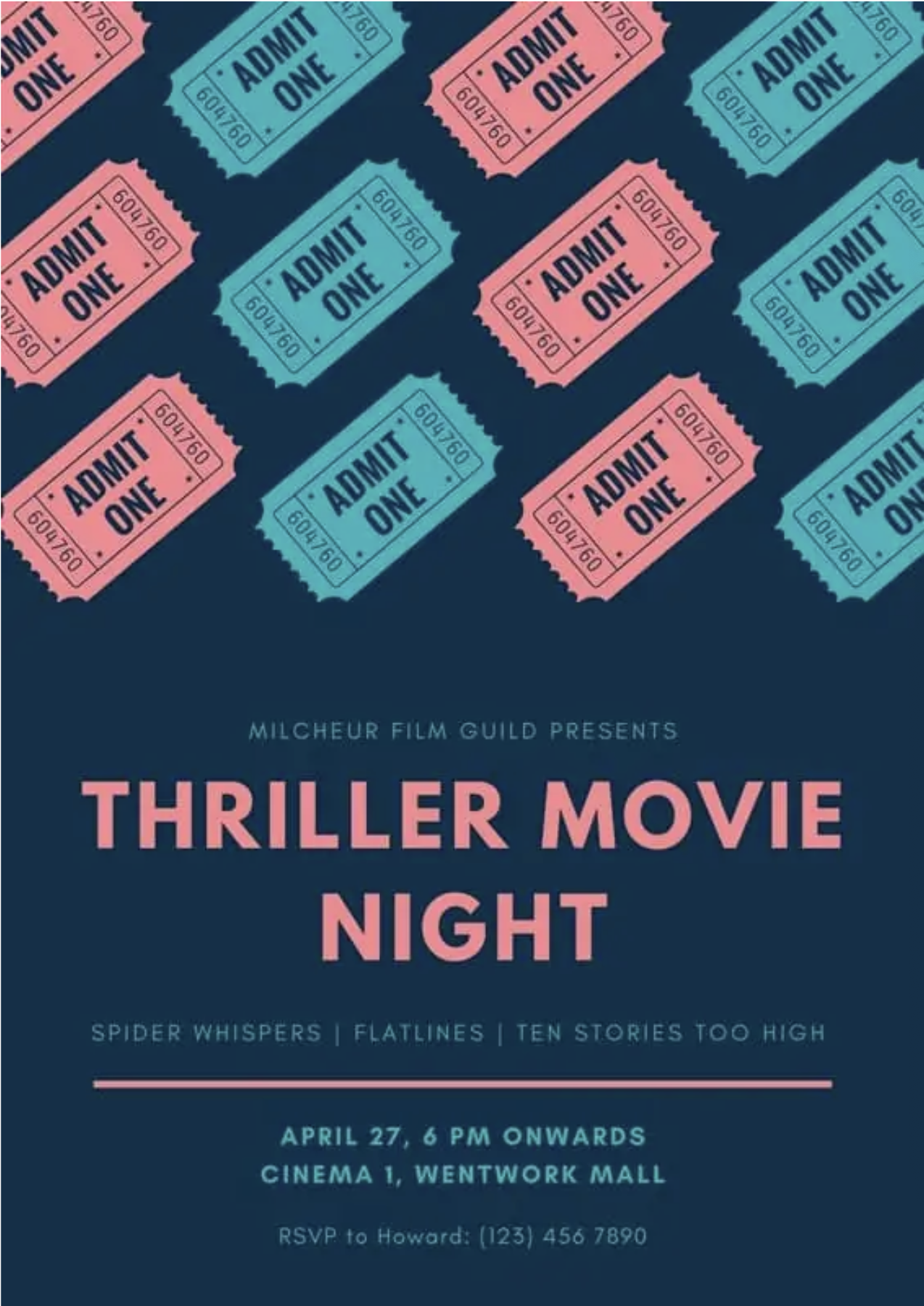

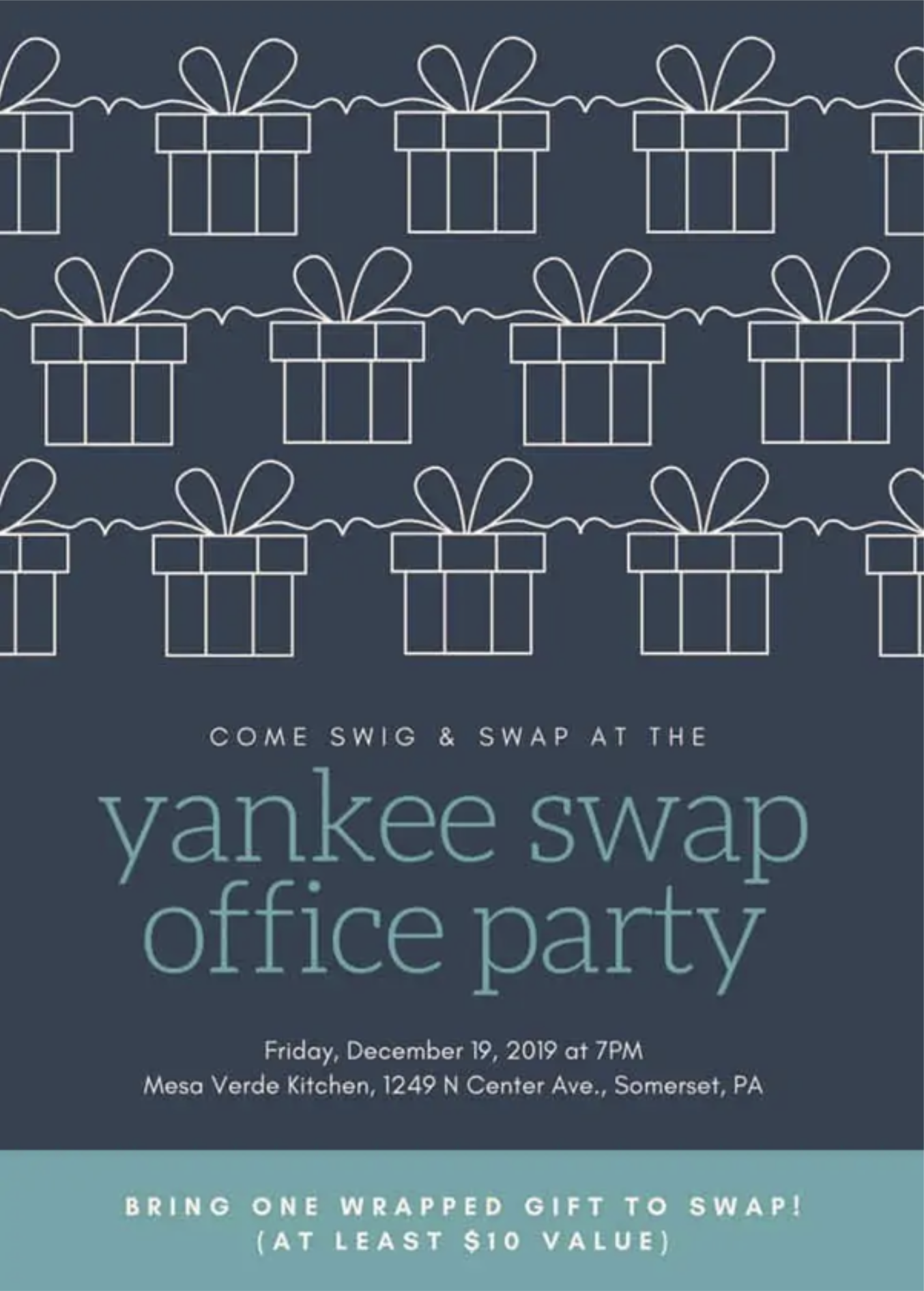

Repetition

Repeating design elements throughout a composition helps to improve the consistency and unity within the design.

Logos, typefaces and colours are examples of elements that should be repeated when designing a cohesive identity for a brand.

Finding a consistent and relatable graphic indicating the start or end of an article in a magazine or website is another example of effective repetition.

Warning: Be careful not to overdo it. Too much repetition can become monotonous!

You can use repetition to create elements in a design by combining elements into patterns or textures.

Alignment

Alignment is about connections. Assets you place should have a visual connection to something else in a composition. Alignment is one way to organise assets visually. Assets in your design can be aligned in a variety of ways, depending on your design requirements.

We often associate alignment with text. Text is often more legible when left-aligned because it creates a consistent starting point for each line of type. We see left-aligned text in books, magazines and on the web.

Other elements in a composition can also be aligned to the left, helping to connect them visually.

Centring elements can help with symmetry. However, components that do not conform to the alignment can look out of place. Greeting cards and wedding invitations commonly use centred text. Centring creates inconsistent start and endpoints and can make reading a more extended section of text more difficult. For these reasons, centred text should be used sparingly.

A connection can be made both horizontally and vertically, and the choice of alignment will depend on other design decisions and principles.

To ensure that alignment is precise, you can use tabs, guides, grids and alignment features available in all the Adobe software components.

If you are designing on paper, use a pencil and ruler to lay down some temporary guidelines.

Proximity

Closely related design elements should be grouped near each other. This is to establish clear visual units and relationships. Avoid scattering related elements around a layout unless they are visually connected by some other means.

Aspects of proximity you may have unconsciously recognised include:

- captions should be placed near the graphic they relate to

- subheadings should be spaced closer to the paragraph they relate to than the previous unrelated paragraph

- elements within a logo should be close together so they form a single compact unit.

Proximity is about creating and reinforcing the relationships between elements. The closer together they are, the stronger their relationship. (Note the proximity of the caption next to the dog's attempted catch in the image above.)

Balance and symmetry

We naturally prefer things to balance and can subconsciously feel uncomfortable or tense if something is out of balance. This applies to the layout of elements in a design.

Balance is achieved by careful placement of elements next to each other and with the weight of each component distributed evenly. The components' size, shape, colour and tone determine their weight in a layout.

Symmetrical balance

Symmetrical balance is achieved when elements are placed evenly about a central axis of a composition to create a mirror image of the elements’ overall shapes and spacing.

This formal, symmetrical balance is straightforward to achieve and is a good choice if you want your design to imply dignity, strength and dependability.

However, it can also be considered boring, old fashioned and predictable.

Asymmetrical balance

Asymmetrical balance can create more dynamic layouts.

However, it is not as simple to achieve.

Considering the effective ‘weight’ of elements–solid filled or coloured features will have more effective weight. Smaller unfilled or greyscale objects have less.

Use multiple, or more, minor details to balance a more significant single element (see the image below).

Note: Images generally have more weight than a similar-sized block of text.

Radial balance

With radial balance, elements radiate out from a centre point in a circular arrangement. Components can be evenly spaced and sized for a more formal symmetrical radial balance or be asymmetrically arranged for less formal results.

Hierarchy

Hierarchy in a composition is achieved when there is a clear order of importance. You can create a hierarchy by distinguishing elements using contrast, size, shape, style, colour, movement, or a numbered sequence.

In documents containing text, hierarchy is created using styles for headings, subheadings and body text.

On a poster, the main graphic might be used to attract the initial attention of a passer-by who will then see the title text, followed by the smaller details.

Larger documents might be broken up into chapters and sections. Large technical documents often have each heading, subheading, or paragraph(s) numbered sequentially (e.g. 2.39) for quick cross-referencing.

Movement

Movement can be used to convey energy, even with a static page.

Angling text forward, using lines and applying motion blur are all ways to show movement in a static document. Consider the path the viewer’s eye will follow. Does the movement match the motion?

Depth

On a 2-dimensional surface, the illusion of depth and distance between elements can be simulated and manipulated in a variety of ways.

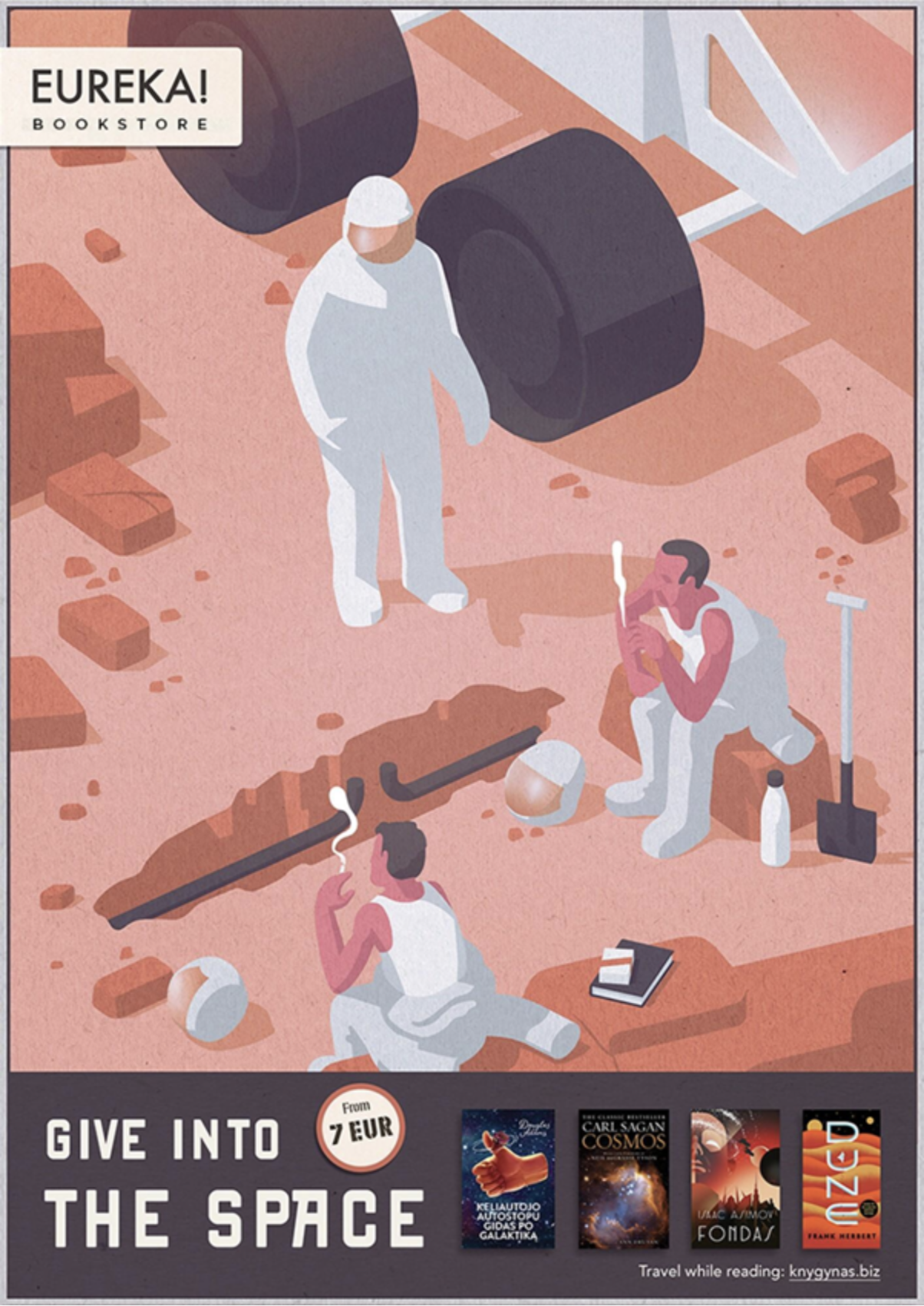

We can imply objects and elements have a 3-dimensional form and volume by projecting isometric (30°/60°) or oblique (45°) faces.

Longer projected faces imply taller or larger objects.

Photographing objects from an angle helps to convey their volume.

Perspective

The further away an object is in our vision, the smaller it appears. We can use this principle with one, two or three vanishing points.

One-point perspective

Used when viewing something face-on. A single vanishing point with and all parallel lines converge at this point. Elements get smaller as they get closer to the vanishing point.

Two-point perspective

Two vanishing points are used and lines on each facing side of an object go towards a different vanishing point.

Three-point perspective

This is the most true-to-life method of drawing perspective. It uses a third vanishing point for converging vertical lines. It only really becomes useful for a very tall object, such as a skyscraper. It is difficult to apply and is primarily used in illustration and drawing.

Lighting, shading and shadows

Brighter objects or elements tend to feel closer. Using gradients and shading on components can help to imply they have a 3-dimensional form.

We expect physical objects to cast shadows, and the qualities of a shadow tell us how big and how close to a surface an object is. Drop shadows, if applied effectively, can provide depth to an otherwise flat design.

Part A: Find design elements and principles

It is important to be able to recognise elements and principles of design in the world around us. Identifying elements and principles will help us better understand how to use them in our own design.

Your task is to capture an existing design then identify and describe the use of one element and one principle in an existing piece of design.

You could choose to search online (the websites listed below have great examples):

- adsoftheworld.com – Advertising examples

- thedieline.com – Packaging design

- behance.com – Designer portfolios

- impawards.com – Movie posters.

You could also choose to find examples in your area. Posters, magazines, billboards books, and architecture are all good places to look for design elements and principles.

Use canva.com or Adobe software to create a single-page presentation that identifies one element and one principle, and describes their use.

Share your presentation in the forum.

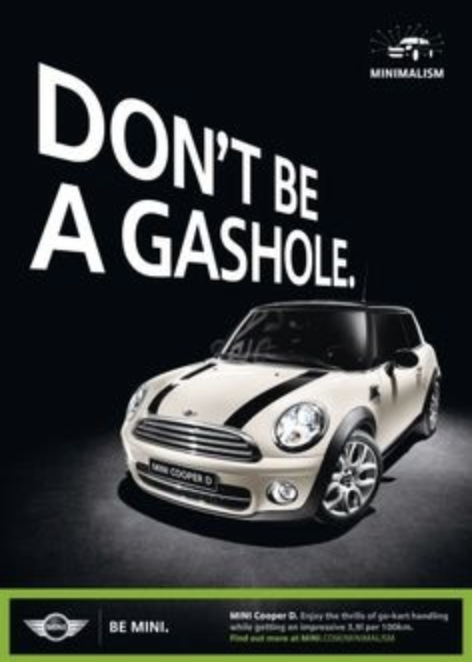

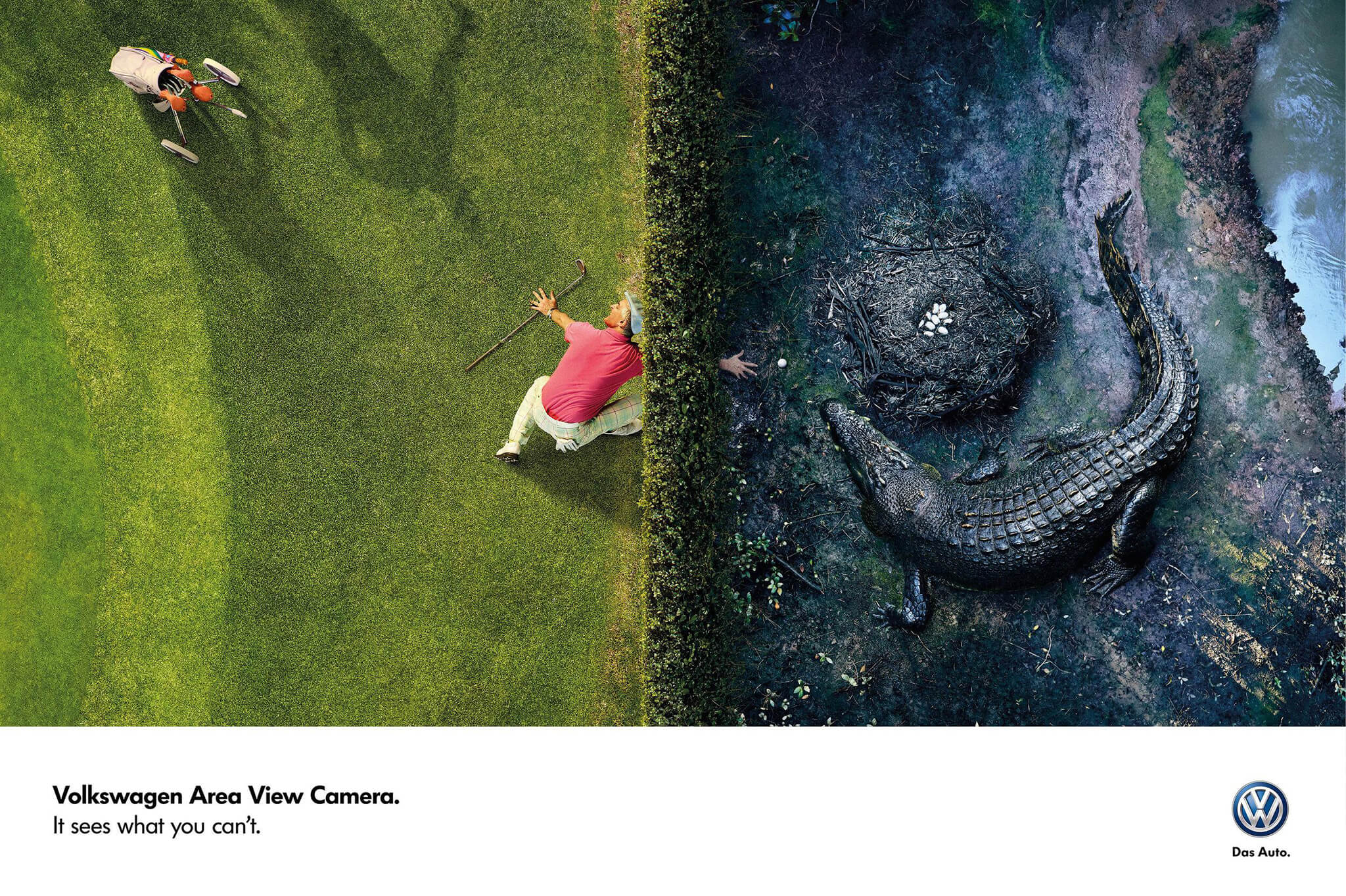

Have a look at the following example:

Space

This Volkswagen ad uses space to create a focal point in the centre of the composition. The use of space between the golfer in the centre and his playing partner (implied by the shadow at the top) helps to convey he is the one in danger.

Contrast

The contrast in colour, tone and imagery between the left and right sides of the image, helps to emphasise the danger. The use of a complementary coloured shirt on the golfer helps build the contrast.

Part B: Use design elements and principles

This activity is similar to Part A, except this time you are to create a composition that exemplifies one element and one principle of design.

You can create any composition you like. This could include:

- a poster

- an artwork

- a photographic composition.

Using Canva.com or Adobe software again, create a single-page presentation of your composition that identifies one element and one principle, and describes their use.

Get creative! Share your presentation in the forum.

Have a look at the following example:

This composition uses line and repetition.

Lines are created by following the point where the pillars meet the wall and the curved arches. The lines converge at the centre of the image, giving a strong one-point perspective.

The repeating pattern of pillars and curved arches guide the viewer toward the centre of the image.

In this topic, we covered design elements that are fundamental to all design. These elements help create images that convey mood, draw the eye in a particular direction, or evoke emotions. Design elements include point, line, shape, texture, colour, space, pattern, and many more.

The principles of design are rules a designer follows to create a compelling and attractive composition. Fundamental design principles can include emphasis, balance, alignment, contrast, repetition, proportion, movement, and white space.

Additional resources

Here are some links to help you learn more about this topic.

It is expected that you should complete 12 hours (FT) or 6 hours (PT) of student-directed learning each week. These resources will make up part of your own student-directed learning hours.

Elements of Design

Principles of Design

Passion Projects

Passion projects are small projects that are outside of class and closely relate to your own interests. Throughout the year, students are encouraged to take on passion projects to develop further their abilities. Lacking ideas? Check the lists below: