In this topic we will cover the following:

- What is packaging?

- The packaging design process

- Packaging is a silent salesperson

- Meeting legal requirements

- Operational considerations

- Sustainability

- Structural design

- Packaging materials.

Packaging is the material that encloses and protects products for distribution, storage, sale, and use.

Packaging design includes strategic and creative work, graphics, colours, text, layout, physical structure, and material choice.

Products need packaging

Packaging protects products from theft or physical damages. Some packaging protects consumers from the product. Packaging also preserves and extends shelf-life by preventing contamination from microorganisms, air, and moisture.

More than just a box

Packaging sells and packaging communicates.

Packaging is a marketing tool that makes products visible and appealing. Effective packaging attracts attention and makes the product stand out from the competition. It draws consumers in with a compelling brand story and informs them of valuable information, influencing purchase decisions.

Make it easy

Packaging makes products easier and more convenient for consumers and retailers to handle. Consider ease of opening, closing, stacking, carrying, and recycling during packaging design.

What do I need to know?

Packaging communicates information such as how to use, transport, recycle, and dispose of the product and packaging. It tells the consumer regulatory and manufacturing information. Packaging informs the consumer about what (and how much) is inside.

What are you packaging?

Start the packaging design process by answering these three questions.

- What is the product?

- Who is buying the product?

- How are people buying the product?

What is the product?

An easy one to start. This question will help you determine logistical musts for your product packaging.

What are you selling and how big is it? What materials is it made of? Is delicate, fragile, or heavy?

Who is buying the product?

A product’s packaging should appeal to its ideal consumer. Personas can provide direction here.

- Is the product supposed to be used by men, women, or both?

- Is it for children or adults?

- Is it geared towards people who are environmentally conscious?

- Is it for those on a budget or with a high disposable income?

Products for older adults may need larger text. Items geared towards an affluent customer will need to consider materials that create a feeling of luxury. Environmentally conscious shoppers do not want to buy eco-friendly products packaged in plastic.

How are people buying the product?

You want to think about packaging differently depending on where it is sold and how it gets to the consumer. Packaging requirements for e-commerce are different than those for bricks and mortar stores.

How will the product ship to the retailer and be stored? A large supermarket or department store buys in bulk and will have different packaging requirements compared with a small boutique.

Start designing

Focus on the purpose, structure, and experience of the packaging.

Purpose

Identify the purpose of the packaging from a legal position, a marketing perspective, and an operational point of view. What information needs to be included?

Establish how you will protect the product.

Be realistic. Are there time, budget, or resource constraints?

Structure

How does the package open and is it intuitive?

Experience

Think about any unboxing video ever. From the first impression of the box that the product was shipped in, the consumer is having an emotional reaction. Are they excited to open it up?

What feelings do you want to evoke when consumers interact with the package? Consider layers, colours, material, and texture.

A product's packaging is an opportunity to present a brand's messages, convey important information about the product, entice the target audience with visuals, and meet any labelling requirements.

Marketing

What is the value proposition of the product? What will entice consumers to buy?

Packaging is an opportunity to market a product and brand. Include brand assets such as logos, slogans, colour palettes, and fonts. But packaging can go further.

Use your packaging to convey subtle messaging to build or capitalise on a brand, tell an emotive story, differentiate the product and brand from competitors, and add to an overall consumer experience.

Product

The product name and logo, if it has one, should be clear. The product branding is usually more prominent than the company logo.

Company brand

Company logos are important. They connect products to established brands and make them recognisable. A company’s logo should be visible, especially from the front.

Co-branding

Co-branding, or brand partnership, combines the brand awareness and market strength of two or more brands. If the product is a collaboration between two companies, how will you capitalise off both brands? Which brand is the headliner, and which is the support act?

Chocolate milk madness

When Lewis Road Creamery partnered with Whittaker’s to produce chocolate milk in 2014, it created a frenzy. Stores sold out within minutes and purchasing limits were put in place.

Lewis Road Creamery launched its chocolate milk producing the smallest batch they could – 1,000 litres – thinking they may not be able to sell it. Two weeks after launching they were producing 24,000 litres a week and still could not meet demand.

Lewis Road Creamery was a small company in 2014 but had a loyal following with deep emotional connections. Their branding and packaging are simple and sophisticated, attracting a higher price-point than competitors. The Whittaker’s brand, which was (and is) well established, trusted, and loved, was a logical partnership.

Imagery

Imagery includes photos of the product or ingredients, illustrations, or a combination of the two. Use imagery that connects your brand story and product to your target audience.

Colour

Colour is an excellent source of information. Colours can have dramatic and profound effects on consumers’ thoughts, feelings, and behaviours.

Consumers look for quick visual cues such as colour, to help purchasing decisions.

But which colours are right for your packaging? Colours may have specific meanings or associations in particular contexts. Always consider the context your packaging will be used in.

Buyer demographics to consider:

- Age

- Culture

- Gender identity

- Global location

Watch the video to explore colour and psychology in different cultures.

Creating your information architecture

You have beautiful photos of your product in action, a brilliant testimonial from a customer, a witty tagline that explains how awesome you are, and a great graphic showing customers how to use your product. But when a shopper looks at your packaging, they are probably only going to remember one thing. What do you want that to be?

Pick the one thing you want consumers to know about your product. Make it the centrepiece. Then add two or three things you want to highlight once they have picked up your product (or clicked on the link) that will close the deal.

There are some amazing and creative types of packaging on the market today. Check out thedieline.com and packagingoftheworld.com for packaging inspiration.

Packaging communicates information required by legal and industry regulations. Some products will also have legal requirements on packaging materials to ensure consumer safety. This is particularly important in the food, beverage, pharmaceutical, and cosmetics industries.

Labelling

Labelling requirements depend on the industry, product, and market. Always research labelling requirements early so you know what needs to be included on the packaging and how much space it will take up. Utilise all surfaces and use appropriate type sizes.

Food

Most food labels in New Zealand include;

- Date marking – use by, best before

- Name or description of the food

- Ingredients

- Nutrition information panel

- Directions for use and storage

- Warning and advisory statements such as allergy declarations

- Name and address of the company/manufacturer.

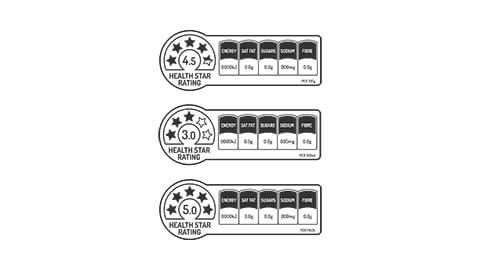

Food packaging may also include health star ratings, health and nutrition content claims, and certifications such as fair-trade and palm oil-free. While this may be included as a marketing tool, these claims are still subject to standards and rules.

Bookmark the Ministry of Primary Industries (MPI) requirements for labelling and composition and their guidelines: ‘A Guide to Retail Food Labelling’.

Cosmetics

Some cosmetics contain hazardous ingredients so it is important that packaging protects and informs consumers. Labels must include;

- Product name

- Hazards and safe use information

- Ingredients listed from highest concentration to lowest

- Manufacturer contact details

- Batch codes

- Disposal recommendations.

Certifications such as cruelty-free, vegan, and paraben-free could also apply.

For information on cosmetics labelling, refer to the Environmental Protection Authority.

Pharmaceuticals

Rules specify how to label the pharmaceutical name, dose, strength, concentration, how to administer, warnings, storage, and even colour. Assign space for dispensing (patient) labels, batch numbers, expiry dates and so on.

Detailed information for the pharmaceutical industry is available from Medsafe and PHARMAC.

What is it made of?

There can be legal requirements for packaging material. For example, any packaging component that may come into contact with food needs to be non-toxic. Depending on the product and industry, packaging may need to be developed in collaboration and signed off by toxicologists, food scientists, and packaging engineers.

Do not consume if...

Tamper evident packaging protects the consumer from contamination, alerting them to tampering. This is important in the food, beverage, pharmaceutical, and cosmetics industries in particular.

Tamper evident packaging:

- Uses at least one barrier to prevent unauthorised unwrapping.

- Makes it impossible to access the container without disturbing the barrier. If the barrier has been disturbed, it should be obvious.

- Barriers should be hard to duplicate.

- The packaging may include instructions for how to detect tampering and what to do such as “do not use if seal is broken.”

The next time you do a grocery shop, look at the packaging. How does the packaging protect against and communicate, evidence of tampering?

Labelling on packaging can be used to communicate important information for people in a warehouse, shipping company, retail, and end-users.

Communicate handling instructions

Does the product need to be kept within a specified temperature range? Stored upright? Is it fragile or heavy? Is it flammable?

Communicate care and handling information on the packaging by using recognisable symbols and words.

Stock management and purchasing

What you put on packaging helps stock management and purchasing. Without stock keeping units (SKU) and barcodes; managing inventory and processing a transaction would be time-consuming, impractical, and open to human error.

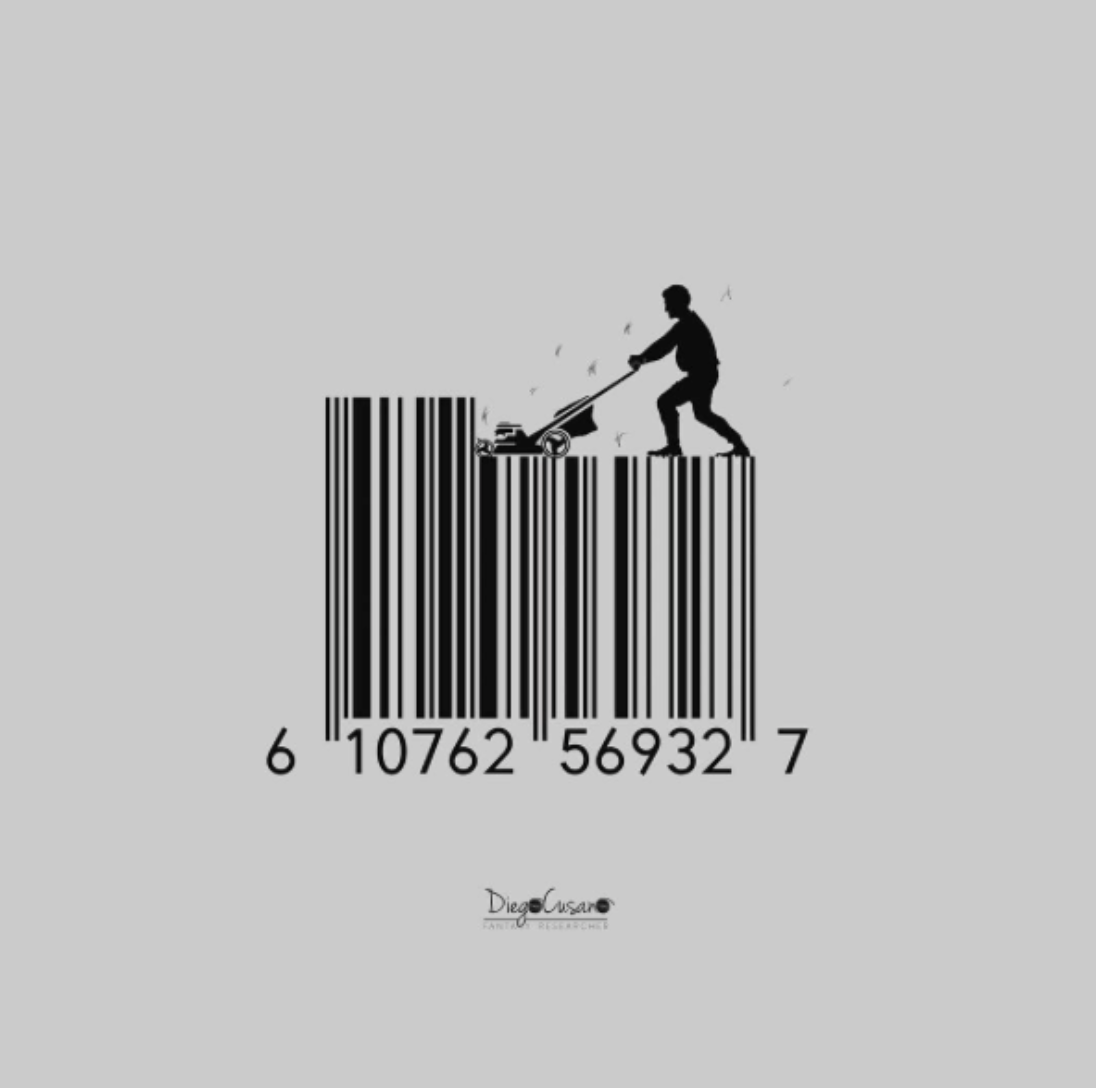

Barcodes

There is no doubt about it… barcodes can be boring! However, they are a crucial component of effective packaging, especially in an environment like a supermarket which deals with fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG).

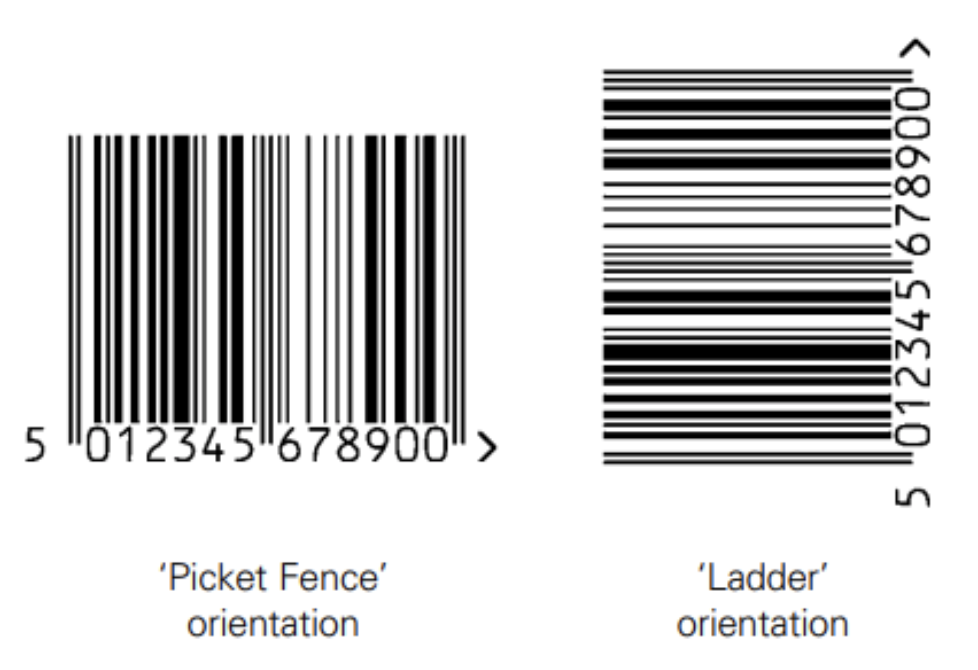

Most retail packaging will require an EAN-13 barcode. Barcodes placed in the correct locations and the right orientation make it faster for retail workers to scan items. Barcodes have specific size, orientation, and colour requirements.

Demystifying EAN-13

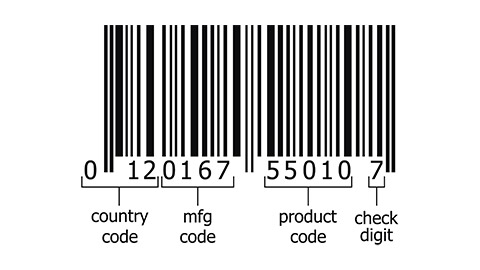

The standard used for retail barcodes across the world is the EAN-13 barcode. It consists of a series of black bars and white spaces with a string of 13 digits underneath. These digits are known as the “Global Trade Item Number” or GTIN.

GS1 is a global organisation that provides companies with the tools necessary to uniquely identify the products they make and supply. GS1 provides companies with a GTIN prefix that includes a country code occupying the first three digits and a company/manufacturing code (usually four to six digits).

The last digit in a GTIN number is called a “check digit”. It is a hash, or calculated digit using all the preceding numbers. The check digit ensures that when a barcode is scanned, it is only successful if scanned correctly.

The remaining digits are used by companies to identify each of the unique products they make and supply.

The rules

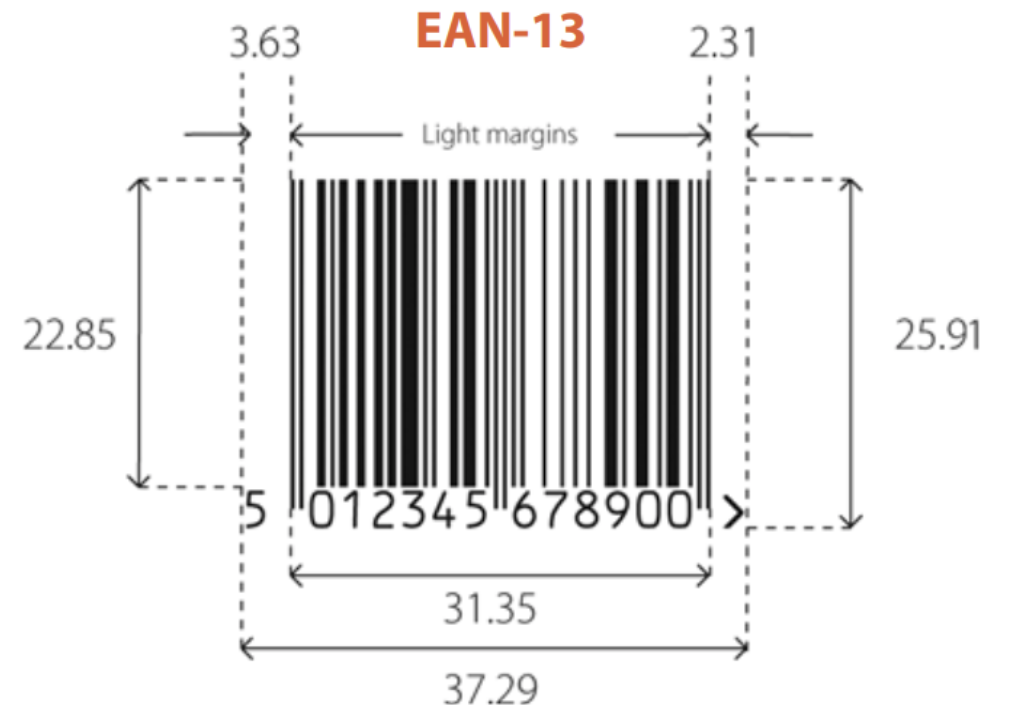

Standard dimensions

These are the standard dimensions for an EAN-13 barcode and are considered the 100% size. All measurements are in millimetres. For use in retail scanning, the barcode can be scaled between 80% and 200%.

'

Black on white

Scanners detect contrast between the bars and the background, so it is important that this contrast is significant. Bars must be dark on a pale background. Light bars on a dark background will not be registered by a scanner. Black on white is best. Colours must be pure or spot colours, not CMYK. You can use colours besides black on white, but only colour combinations that are picked up in high contrast under red light.

Do not truncate the bars

Shortening the bars to make a narrower looking barcode decreases its scalability, slowing down scan rate in supermarkets and other high volume retail environments.

Orientation

Barcodes printed on narrow curved surfaces like drinks cans, bottles can have issues scanning. Rotating the barcode so the go around the curve increases its scalability.

You can read more about barcode requirements in the ‘Bar coding basic user guide’ by GS1 New Zealand. This guide includes common problems to avoid.

Getting creative

While there are requirements and restrictions to consider when using barcodes, you can still get a little creative with them. You can add flourishes and embellishments to the top and bottom or add illustrative elements.

Sustainability and environmental responsibility are important considerations for all businesses. With global awareness of the impact of human-driven climate change, it is increasingly important for companies to strive for sustainable alternatives to traditional practices.

It is important to think of the full packaging lifecycle – From creation all the way through to how the consumer will dispose of it.

Waste hierarchy

The waste hierarchy is a framework for establishing the order of preference for different waste management options. These are commonly referred to as the three R’s. First reduce waste. If there is waste that cannot be reduced, reuse it. Finally, any remaining waste should be recycled.

There is a growing trend to add refuse as the first step, meaning if a product has excess packaging, consumers will refuse to buy it!

- Refuse

- Reduce

- Reuse

- Recycle

- Rot

Reduce

Eliminating unnecessary packaging prevents waste from entering landfill. Consider how much packaging is actually necessary to protect the product, convey information, and establish a presence on the shelf.

New Zealand banned the use of most single-use plastic bags in July 2019. Consumers and retailers needed to adapt, and bringing your own bags became more prevalent. In the twelve months following the ban, more than a billion bags were kept out of landfills ('Extraordinary effort from Kiwis sees plastic bags cut by a billion, one year on from ban – Ministry for the Environment’ 2020).

Reuse

Once a consumer has the product at home, does the packaging have a useful life beyond its original function? Can it be refilled or put to another use? Does it continue to protect the product after purchase?

Using durable materials like glass, increases the likelihood the packaging will be reused if the size and shape is useful. Using durable materials when it is likely the packaging will be disposed of is less environmentally friendly.

Recycle

What remains of a product's packaging after it has been reduced and reused, needs to either be disposed of, or preferably recycled. Paper, cardboard, glass, tin, steel, and aluminium can all be recycled. Some, but not all, plastics can be recycled. But consider the energy and resources required to create the packaging and recycle it.

Sustainability as a selling point

Eco-conscious consumers make purchasing decisions not just on the product, but also the packaging (or lack of).

The following video shows how Feed My Furbaby built sustainability into their award-winning packaging design. Watch the video and note how sustainability and good design was built into every packaging level.

Creating a circular economy

There is a growing movement to create a circular economy with consumers sending used packaging back to the retailer or manufacturer. This packaging is then either sanitised and reused or recycled into another product.

The following video shows how Woop considers sustainability in their packaging and participates in the circular economy movement.

Local examples of returning packaging to the retailer or manufacturer include Woop’s Back to Base programme, Aleph Beauty’s Re Aleph programme, Emma Lewisham’s Beauty Circle, and CaliWoods’ Cali Blade Take Back Program.

Once you have figured out the purpose and what needs to go on the packaging, you need to consider the structure of the package. How does it open? How will the product stay safe and look great?

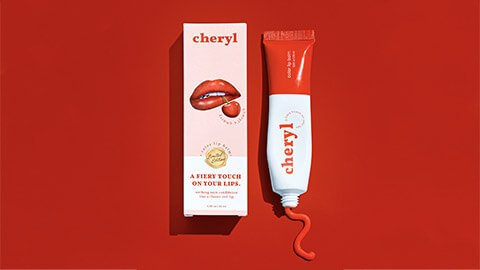

Three levels of packaging

Primary packaging

Packaging that is in direct contact with the product. Its purpose is to protect, contain, and preserve the product as well as inform the consumer. The consumer engages with the primary packaging long after the secondary and tertiary packaging has been disposed of. Therefore, most of your budget should be spent on this packaging.

Secondary packaging

Used for stock keeping (SKU), branding displays, may include tamper evident packaging, and makes stacking and display easier. This is often the type of packaging seen on the shop floor.

In the following image, the box on the left is secondary packaging and the tube on the right is primary packaging.

Tertiary packaging

Used for bulk or transit packaging and will often contain multiple units. Tertiary packaging traditionally was used behind-the-scenes in the warehouse or backroom and not seen by the consumer. However, with more consumers shopping online, and receiving their packages via courier in tertiary packaging, this level is becoming important in the consumer experience.

Watch the video to see examples of primary, secondary, and tertiary packaging that make their way to the consumer.

Form

Common types of packaging include boxes, bags, gusseted pouches, and sleeves.

Boxes

Boxes come in a range of formats and sizes, with different closure systems. Boxes can either be rigid, holding their shape or folded flat making them easier and more economical to transport when empty.

Most retail boxes for fast-moving consumer goods are printed flat, die cut, and folded. Some boxes are designed to be glued closed while others use flaps and tabbed closures making it possible to seal and reseal.

Bags

Made from paper or plastic, flexible bags or pouches come in a range of sizes and formats. Bags are often printed on rolled stock and sealed during the filling process.

Pillow pouches are heat-sealed at the back, top, and bottom. They are often used for chips, pasta, and snack foods.

Gusseted pouches

Gusseted pouches can be heat sealed and folded to create a flat bottom. This means they can stand on their own. The top of a gusseted pouch can be heat sealed or folded and glued. You often see coffee sold in gusset bags.

Variations of the gusseted bag are used for wet products. The standard milk carton is a variation on the gusseted bag.

Sleeves

Sleeves can be used to package pre-prepared trays, hold sets of products together, and make it easier to present irregularly shaped products.

Common packaging materials include plastic, glass, steel, aluminium, paper, cardboard, and wood. When you are deciding which material to use, think about the environmental impact, cost, durability, and how well it protects and encloses the product.

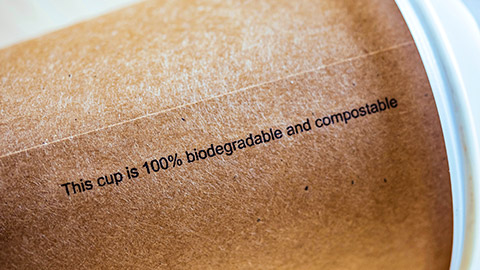

Decoding recyclable, renewable, and compostable

To limit environmental impact, consider whether packaging material is recyclable, renewable, compostable, or degradable.

Recyclable

These materials can be used again following chemical treatment. Common recyclable materials include paper, cardboard, glass, and aluminium.

Some plastics are recyclable, but the extent depends on the region. A symbol on plastics consisting of a number and code, helps consumers identify if something can be recycled. Only plastics 1 and 2 are recyclable in all areas of New Zealand, except for the Chatham Islands which only accepts plastics 1 (WasteMINZ 2020).

Renewable

These materials are bio-based and naturally renewed. Bio-plastic made with sugarcane is an example of a renewable material.

Compostable

These materials can break down without leaving toxic remains within roughly 90 days. The term “degradable” can be misleading to consumers as it implies the same as compostable however, there is no specified time.

Which material to use?

Evaluate the benefits and disadvantages as they relate to packaging a specific product.

Plastic

Flexible, light, and durable. Plastic can be food safe and used at a variety of temperatures. Visually it allows a variety of designs including transparent or opaque. However, it is challenging to recycle correctly.

Glass

Glass is non-porous and non-toxic making it perfect for food and beverage packaging. Glass preserves flavour and freshness, as well as being aesthetically pleasing. It is 100% recyclable provided it is washed out and not contaminated.

The downsides of glass are that it requires a considerable amount of heat and energy to manufacture and is breakable. Secondary and tertiary packaging needs to be considered to protect the primary packaging.

Aluminium

Aluminum is resistant to corrosion, lightweight, recyclable, and offers great protection from light, oils, and oxygen. It is often used in food and pharmaceutical packaging due to being non-toxic, hygienic, and to extend shelf life.

Metallized PET is plastic with a thin layer of metal, typically aluminium. It uses fewer materials than straight aluminium but cannot be recycled without separating the plastic from the metal, which is often impractical.

Paper and cardboard

Inexpensive, flexible, recyclable, renewable, and light. Corrugated cardboard is strong and used for shipping and storage. It is easy to print branding and design elements directly onto the material. It is likely that at least one level of your packaging will be composed of paper and/or cardboard.

Fast moving consumer goods

FMCG (fast-moving consumer goods) are products that are sold quickly and at relatively low cost. Examples include non-durable goods such as soft drinks, toiletries, packaged food, snacks, and confectionery.

Consumers have more options today than ever before. The FMCG market is competitive, and it can be challenging to get consumers to notice a new brand or product. Consumers scan the shelves and quickly decide what products to pick up and which ones to ignore.

Good packaging design helps brands and products to stand out from the competition. Packaging could be just a simple bottle with label attached to multiple layers of boxes and inner packaging.

Packaging analysis

Complete this activity at your local supermarket (for example Countdown, Four Square, New World, or Pak’n’Save). Let the manager know that you are conducting research for a student project. Ask if it is okay to photograph products.

If you cannot physically visit a supermarket or spend sufficient time in a supermarket, complete this activity via Countdown, New World, or Pak’n’Save’s online shopping websites.

Your task

For this task, you are asked to take photos of effective packaging design and analyse the packaging. Along with your photos ensure that you:

- Record the brand and product name.

- Take a photo that shows the product and the competitor’s product.

- Document what you find on Canva or a similar tool.

(You are not required to purchase any products.)

Analysis

Identify a product that stands out from the rest. Answer the following questions to guide your analysis.

- Where is the product positioned in relation to eye level in the supermarket?

- Is it a convenient shape and easy to hold?

- How is it distinctive from the competing products?

- How is it similar to competing products?

- How is it stacked on the shelf?

- Is the product recognisable from all sides?

- What benefits are being offered?

- What is the message being communicated?

- What kind of imagery has been used? Photography, illustration, or a mix?

- Is the imagery literal, abstract, or telling a story?

- What substrate has been used? ie: cardboard, plastic, foil etc

- Who is the target consumer?

- What is the hierarchy of information? Are the most important elements bigger and brighter?

- Do you think the packaging and its design are effective? Why?

Share your analysis in the forum.

Packaging encloses and protects products for distribution, storage, sale, and use. Packaging is a marketing tool enabling products to stand out from the competition and influence consumer decisions. Packaging makes is easier for consumers and retailers to handle and is an important communication tool.

Research your product before designing the packaging. What is the product? Who is buying it? And how are they buying it? When you design packaging think about the purpose, structure (how does it open?), and experience you want the consumer to have when they interact with the packaging.

Labelling and package design is important for marketing, legal requirements, and operational considerations.

- For marketing, consider the product and company branding, co-branding opportunities, imagery, and colour. Apply information architecture so key messages are not competing with one another.

- To meet legal requirements packaging has specific requirements based on product, industry, and market. Examples of legal requirements include nutrition information panels, date markings, and batch codes. The use of non-toxic materials and tamper evident packaging may also apply.

- Operational requirements include handling instructions and barcodes.

There are three levels of packaging – Primary, secondary, and tertiary. Consider form and material when designing the structure of your packaging.

Excess packaging annoys consumers and wastes resources, contributing to climate change and landfill. Assess sustainability over the whole lifecycle of packaging - From the resources used to create the packaging through to how the consumer will dispose of it. Apply the 3 Rs in order of the waste hierarchy:

- Reduce

- Reuse

- Recycle

Consider creating a circular economy where consumers can return clean, empty packaging to the retailer or manufacturer.

Additional resources

Here are some links to help you learn more about this topic.

It is expected that you should complete 12 hours (FT) or 6 hours (PT) of student-directed learning each week. These resources will make up part of your own student-directed learning hours.

Inspiration

- Packaging of the World

- Aztec chocolate packaging

- Ugandan soft drink

- Trident (chewing gum) from Portugal

- Philippine rice

- Steve Simpson artist

- 20 Creative Packaging Designs that are not afraid to get personal

Regulations

- Package design legal requirements

- Australia's 'Made in Australia' labels

- A short history of packaging

Sustainability