Principles of animation

When we consider a new project, we really study it…not just the surface idea, but everything about it.Walt Disney

Animation is everywhere and though people seem to enjoy the feel and emotion it attracts, they do not realise the work it entails and how animators can creatively achieve this by breathing life onto a blank canvas.

'Animation' can be defined as 'the rapid display of a sequence of images to create an illusion of movement'. The most common method of presenting animation is as a motion picture or video.

Everyone is exposed to animation through multiple avenues: entertainment, education, advertisement, scientific models and studies, creative arts, gaming and so much more.

Think of your favourite animated movie. How do the creators of the movie make us believe that the objects and characters they have created are alive?

Simple. It comes down to the 12 principles of animation that were first introduced by Disney animators, Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas, in their book, The Illusion of Life: Disney Animation, which was originally released in 1981.

Upon retirement, Frank and Ollie began to piece together a book about their experience as animators for the Walt Disney Studio. They provide guidelines for animating an action or shot, as well as a set of principles to follow when attempting to bring drawings to life.

The principles form the basis of all animation work. While created for hand-drawn animation, they still also apply to digital animation today.

They are relevant for many different fields, with the most obvious use being for animating a character design.

We will be focusing on the following 6 principles in this topic, and will explore the remaining 6 later on.

'Timing' within animation refers to the number of frames for any action used by the animator. This helps create the illusion that an action is abiding by the laws of physics. By adjusting the timing of a scene, animators can make that scene look either slower and smoother (with more frames) or faster and crisper (with fewer frames).

If you have many drawings that are very close together, the action of the drawing will be very slow. On the other hand, if you have fewer drawings further apart, the action of your character will be fast.

Timing is an important principle in animation as it provides meaning to movement. The speed of an action will define how the audience interprets the emotion behind the action. It plays an essential role when illustrating the emotional state of the character. The animator can establish this through varying the movements to show the character's mood, emotion, personality and reaction.

'Ease in/ease out' is also known as 'slow in/slow out'. This is used when the animator creates any action that needs time to speed up and slow down.

Consider a car, for example, it does not start and stop at the same speed. You will need to create and animate the car to gradually accelerate to reach the speed you want as well as slow down to the halt.

This is one of the most important principles designed to add realism to the movement of characters, otherwise movements will look mechanical and robotic.

To achieve life-like motion, animators will draw more frames at the start of the action, less frames in the middle, and more frames again at the end of the action to create the slow-in/slow-out effect.

These effects also focus on the feeling of the animation. Think about the way it feels to be on a rollercoaster: as the ride reaches the crest of a hill, the cars slow down for effect before dropping into the next plunge.

- Ease in/slow in: used at the start, it is slowed down by having more frames closer together.

- Ease out/slow out: used at the end, it is slowed down by having more frames closer together.

'Squash' is what happens at the time of impact; while 'stretch' occurs before and after the impact.

It can also be used as a quick movement to get the character from one position to another, helping you to create a sense of volume to your object or character (as well as providing the sense of a cartoon-like appeal).

The general rule is that: the FASTER and LONGER the fall, the BIGGER the squash and stretch.

Squash and stretch can act as a tool to emphasise speed, momentum, weight and mass. The more squash and stretch, the softer the object. The less squash and stretch, the stiffer the object.

You can also use squash and stretch to exaggerate facial expressions in a character to give interest to regular emotions that can sometimes be boring and uninteresting. An example may include a character being anxious by biting their nails furiously and looking anxiously with their eyes to the left and right. In an everyday situation that does not happen when we are feeling anxious, however, this technique is used to engage the audience.

Most things flow in a natural and circular curve motion, unless you are a robot, of course. Using the principle of arcs helps animators achieve a natural movement and direction for characters and objects. Consider when a head turns or an arm moves, rarely will they thrust straight in and straight out. Natural movement will often have a slight curve to it.

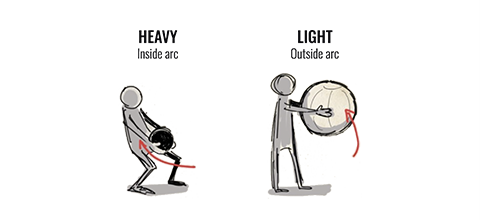

A great example is a character lifting an object--you can usually determine whether the object is light or heavy depending on the character's body language. When lifting a lighter object, the animator will have the object sit outwards of the character's body. The heavier the object becomes, you may place it closer to the lifter's body and create an arc to show the impact.

This way, the audience gets a sense of the object/action simply by recognising its arc (as illustrated below).

Watch the following video to see how the principle of arcs is effectively used in animation.

Anticipation is the lead-up to an action, taking the audience through a planned sequence of actions that will lead them clearly from one activity to the next.

This usually occurs in three parts:

This supports the audience to become prepared for the next movement as they expect it before it occurs (yes, think: anticipation).

This is achieved by preceding each major action with a specific movement. It can be as small as a change of facial expression or as big as a physical action. Consider a character running and slipping on a banana peel--it is through anticipation that the audience will be able to see the character running, as well as anticipate the slip.

Another example is a ball falling off a ledge. If the audience did not witness the ball rolling, they would not be able to anticipate that it would fall; therefore making this movement feel unrealistic.

If we do not have anticipation, the audience will not process what is going on and the action will be complete before they even realise it.

Anticipation is important to animators as it provides their animation with a sense of realism, as well as helping the audience to predict what is to come. This is needed when evoking emotion, as well as telling a story.

How many anticipated moments do you experience when you watch the following clips?

Animators use 2 main approaches to draw out key poses that they would like their character to take.

Using the approach 'straight ahead', the animator will begin with the first drawing, continue to the next, progressing in chronological order--hence the name 'straight ahead'.

However, when using 'pose-to-pose' animation the animator will draw out the key poses in an animated scene--the beginning and end--and once those are complete, the animator will go back to fill in the in-between drawings.

Animators can use whichever technique suits them, or they may alternate between both, depending on the scene or animated action shot.

Pose-to-pose is usually more effective when creating action scenes, as having created the first and last shots, the animator then works backward. This method gives them the control to decide where the character will end up, ensuring consistency size, position etc. If they were to make a mistake, they can work within the middle shots without impacting the whole animation. However, if they choose to use the straight-ahead technique, they may be forced to change the whole drawing.

Straight ahead, on the other hand, is more effective for unpredictable animation--think of fires, water, clouds and explosions. This is due to their nature of being natural and unconfined.