In this topic, we will discover the areas of development children will progress through in the early years. The importance of positive and healthy brain development for babies and beyond and how educators play a vital role in guiding children to achieve their milestones.

By the end of this topic, you will understand:

- How development occurs – key concepts for growth and development (intro.)

- The influences and impacts on development (intro.)

- Brain development

- Areas of development

- The importance of learning and development in the early years

- Developmental milestones

- Child attachment.

Most people will probably agree that the way the human body works is quite amazing, and the way our brains develop is even more complex and intriguing. Did you know that "at birth a baby’s brain contains approximately as many neurons as there are stars in the Milky Way (approx. 100 billion) and is about 25% of its adult weight", (P.T Slee, M. Campbell and B. Spears, 2012).

The brain stem

There are many ways to ‘pull apart the brain’. If you think of the brain as a tree, the brain stem (at the back of the head near the neck, connecting to the spinal cord) is the first sprout. For this sprout to flourish and grow, it needs optimal conditions and support, such as safety, water and food – a healthy input. This begins before the baby is born and is affected by the mother and her input, whether physically or emotionally. Essentially, the baby and its brain are altered through the experiences of the mother. The brain stem supports all of our most basic, yet important elements, such as breathing, circulation, swallowing, body temperature, heartbeat and nervous system, so, for the brain to continue to grow, this part of the brain to be set up as a strong base, before sprouting more branches.

How does the information travel around the brain?

A neuron is essentially a nerve cell, a part of the primary function of the nervous system, to take in stimuli and information.

The synapse creates doorways to neurons, which are essentially pathways through the brain, when stimulated they open up new doorways in the brain, or sections of our growing tree.

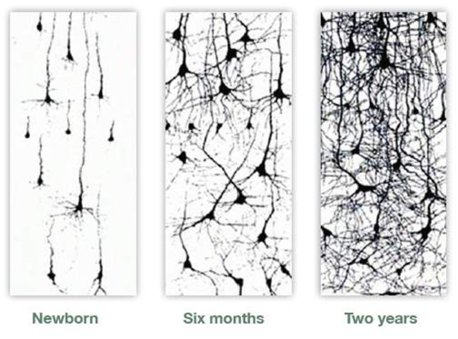

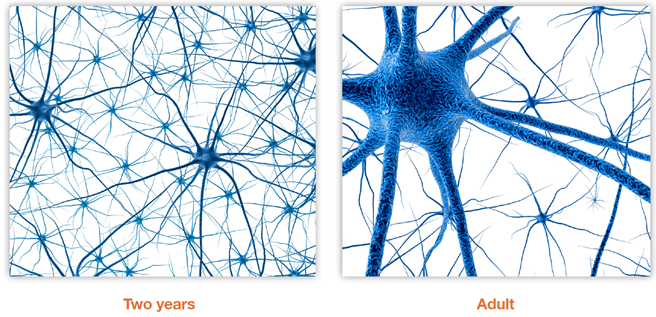

The dendrite is the receiver of information for the neuron, and if the signal is strong enough, the dendrite will send it through the axons – or the channels or tubes between neurons – and on to the next neuron. As we grow, neurons that are rarely stimulated are ‘pruned’, making way for new connections, with about 40% of all synapses pruned during childhood and adolescence.

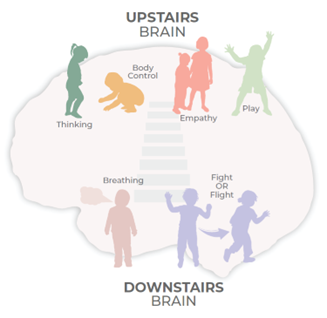

- Upstairs Brain

- Thinking

- Body Control

- Empathy

- Play

- Downstairs Brain

- Breathing

- Fight or Flight

700 new neural connections every second

During the first two years of a child's life, 700 new neural connections are formed every second. It is during the early years that a child's nervous system is most active in making new connections.

Watch

The following almost 2-minute video explains the main parts of neurons (including the dendrites, soma, axon hillock, axon, and axon terminals or synaptic boutons) and how a signal travels from the dendrites of a neuron, down the axon, and to the axon terminals to communicate with another neuron through the release of neurotransmitter and how the signal travels from the dendrite.

Check your understanding

The limbic system

The limbic system is known as ‘the feeling brain’, this will develop next. It supports how we take in the world and ultimately, how we manage it. This is where we support by nurturing the child, creating certainty, safety, emotional support and stimulation. This area includes the body's regulator, nervous system, awareness, anxiety and aggression sector, learning and memory and also hormone communicators, so the child is pulling from this bank to know how to respond to certain situations and stimuli. It also includes the survival mechanism of flight, fight or freeze, informing the body to protect itself by whatever means.

The cerebral cortex

The cerebral cortex is known for its ‘executive function’, where higher action and learning occur. This is made up of four main parts, where we learn to plan and communicate, develop impulse and motor control, learn emotional regulation, and learn social adaptability.

Areas in the cerebral cortex support vision, visual processing, perception, hearing, and sensory processing information. This is also split into what is known as the left and right hemispheres of the brain.

Watch

The following 8-minute video explains through Dan Siegal’s hand model how our brain works. Dr. Daniel Siegel’s hand model of the brain allows us to picture our brain structure and understand why it’s difficult to control our reactions when we’re overwhelmed with strong emotions, especially stress.

Check your understanding

Impacts on brain development

So why is it so important for early childhood educators to know about the development of the brain? Because without the right support and environment, the brain may not develop to its full potential, impacting lifelong learning and development.

Studies have revealed that malnutrition in the early years of children’s lives may prevent them from developing the brain connections that are essential for learning throughout life, and evidence shows that harm early in life contributes directly to the inter-generational transmission of poverty and social disadvantage.

In the early years, children must be supported with a safe environment where they are fed, kept warm and have good medical care, without this support, the brain has been known to stagnate in survival mode. The physiology of the brain (the way it functions) needs to be settled in order for the brain and body to continue optimal development throughout their lives. The child needs to have secure attachments with primary carers and safe environments for exploration and learning.

Toxic stress

It is a normal part of development and life to have to deal with – and learn to deal with – stress. Throughout our lives, the body reacts to life-threatening stress situations by delving into the brain’s response sensors within the brain stem. It prepares our body for fight or flight by increasing our heart rate, blood pressure and cortisol (stress hormone), in preparation to run away or fight for our survival, which we need as humans. When stress happens frequently, is ongoing, or is extreme, this becomes a toxic stress, as the response system becomes constantly active, which is not healthy for development. The body becomes stuck in fight or flight mode, or most likely a state of hyper-vigilance, which is when the body is always prepared to have to survive through hyper-awareness or alertness. When this occurs, a child cannot focus on other areas of their life, settle the physiology of the body (effects of the nervous system) or develop further, as the body and brain begin to alter the biology of the person and the architecture of the brain – with lifelong consequences.

When children experience trauma, they can also go into a disassociated state of ‘freeze’, which can present as detached, uninterested or withdrawn.

However, if a child has a secure attachment figure and a safe nurturing home, and the intervention services and supports are sometimes required, they can often manage this toxic stress.

See the following image, pinpointing the differences in stress (Harvard University, 2020).

- Positive: Brief increases in heart rate, mild elevations in stress hormone levels.

- Tolerable: Serious, temporary stress responses, buffered by supportive relationships.

- Toxic: Prolonged activation of stress response systems in the absence of protective relationships.

Check your understanding

Read the following statements about stress and decide whether they are TRUE or FALSE:

Watch

The following video is part three of a three-part series titled "Three Core Concepts in Early Development" from the Centre and the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. The series depicts how advances in neuroscience, molecular biology, and genomics now give us a much better understanding of how early experiences are built into our bodies and brains, for better or for worse. Healthy development in the early years provides the building blocks for educational achievement, economic productivity, responsible citizenship, lifelong health, strong communities, and successful parenting of the next generation.

The following 2-minute explains how toxic stress impacts healthy development.

Sensitive and critical periods

A sensitive period may last for months or years and is the timeframe where a developing child is particularly responsive to experience or particularly hindered by their absence in relation to the development of the brain. As an example, during infancy this may include the impacts of attachment, sunlight, or even exposure to sensory information and play. A major element during these periods is the plasticity of the brain, where it can change, due to the experiences and influences it is presented with.

Critical periods are a class of sensitive period: that is, when elements of the nervous system require appropriate stimulation during a specific timeframe, in terms of behaviour, cognitive processing and psychological state and wellbeing.

How can educators support brain development?

Educators can support the development of the brain through creating a safe, nurturing and opportunistic environment, where children trust their educators and their environment, feeling safe to learn and explore developmentally safe experiences.

Watch

The following 4-minute video explains the child-version of Daniel Siegel’s hand model of the brain.

The first thing to consider is that development doesn’t occur in isolation; the understanding of the complex interconnection of social, psychological, environmental, and biological factors, including genetic factors that influence child and adolescent health. The use of our development is intertwined within itself, often requiring each to complete tasks, hence why holistic development is so relevant.

Development, although holistic, can be broken down into the following six areas:

- Physical (Motor) Development (Gross and fine)

- Sensorimotor Development

- Cognitive Development

- Emotional Development

- Language Development

- Social Development

Physical/motor development

Gross motor development

This is the development of the physical body, the bones, muscles, limbs and extremities. Gross motor development involves the large parts of the body such as legs, arms and chest.

This can be evident when you observe children rolling from front to back or back to front, standing, crawling, walking, running, skipping, or even demonstrating the flossing dance move.

Fine motor development

This is the development of the small bones and muscles that may be evident when using fingers, toes, tongue, lips or eyebrows. This may become apparent while drawing, manipulating objects such as playdough, using blocks, or even kissing.

Watch

In the following almost 4-minute video, a physiotherapist shows a few simple activities to improve children’s fine and gross motor development in children. The activities recommended can help to:

- improve static and dynamic balance

- strengthen fingers and hands as part of fine motor skills

- improve hand-eye coordination

Sensorimotor/sensory development

The development of our senses is an important part of physical development. This is the exploration of the senses, vision, hearing, smell, touch and taste. When children learn to use their senses from birth to explore their world, preparing the body and brain for learning. The use of the senses helps to fine-tune them and learn about themselves, their bodies and objects within their environment.

At about 5–6 months, babies begin to process visual information, as the vision transforms from black and white, depth perception/3D, to binocular (through both eyes), leading towards 20/20 vision between 6–8 years. Before this, babies use their sense of hearing and taste, primarily to understand what is happening around them, which is why you might see babies moving their heads towards noise, even in the dark, as they rely on sound.

Sensory development may include whacking at a bright object above them on a play mat, chewing on a mouthing toy, putting their fingers in their mouth, poking buttons, and squishing noisy or textured materials. As we grow older, this helps fine-tune skills for such play as playdough or even a game of freeze, where we need to use our hearing to focus our listening skills.

Sensory motor skills also include areas such as:

- Proprioception, which is our connection to our body (muscles and joints) and vestibular system and sense – this is awareness of our body in space (balance and head position). These both support spatial awareness.

- Laterality supports us to cross over our body (midline) and understand left and right. This is needed to complete such tasks as writing and reading.

- Centring, from top to the bottom across the midline. This coordinates the body’s action at the top and bottom of the body, in a fluid motion, such as when we walk.

Watch

The following 3-minute video describes the sensory development needs of different children, including those with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD):

Cognitive development

This is the development of thinking, reasoning and problem-solving skills, required to support us to learn how to tie our shoes, create a collage, complete a puzzle, organise ourselves, or manage how we will deal with an unexpected situation. We learn how to use different types of thinking, such as divergent, lateral, logical or abstract, to manage a problem. This is also the way that we process and organise the information we take in from our senses and the environment – a form of data collection and analyses if you like, with an internal board meeting to work out the ‘next steps’.

Did you know?

Play theory generally refers to cognitive development in younger children.Watch

The following 2-minute video demonstrates a popular game you can play with children to support memory, reasoning and problem-solving skills.

Emotional development

This is the development of emotional expression and regulation, a time to learn how to comprehend, embrace and manage our emotions. It is important for feelings and emotions to be acknowledged, as all emotions are relevant to the person. When we learn about our emotions, we can usually learn to understand the emotions and needs of others, developing such skills as empathy, care and compassion. While children are learning about their emotions, they are egocentric, which means that they do not understand the needs of others, only their own, this skill has not yet been developed.

When young children cannot share, or take an object from another child, it is because they are meeting their own needs, but cannot yet empathise with the needs of the other child.

Watch

The following 5-minute video explains egocentrism in early childhood. (The video stats at 0:20)

As a part of emotional development, children can also learn what affects their emotions or settles them as necessary, e.g. “I just need to have some quiet time and read a book”, “I need to go for a jump on the trampoline”, “I need to take three deep breaths”, “I need to find the right words for me to manage this situation”. As a part of supporting the mental health of children, finding strategies to support their emotions from a young age can have positive lifelong effects on the emotional development and long-term mental health of the child.

Important elements of emotional development also include supporting a child’s identity, self-concept and self-esteem. They help them understand who they are, where they come from and how they fit into their world – assisting a child to build a sense of self-worth.

Emotional development has a major impact on the formation of the rest of a child’s development, including creating and maintaining friendships and becoming resilient in challenging situations.

Check your understanding

Match each element to its description.

Language/communication development

This is the development of a child’s ability to communicate with both self and others in order to interact in their world. This separates us as humans from all other species. There are many theories on how language occurs, such as humans having an innate ability built into them from conception, whether modelling, reinforcement, experience, or self-taught.

Most do agree that, as humans, we are social beings and depend upon language as a means of communication for our survival.

Language development will incorporate both the receptive (understanding of language) and the expressive (the skills to communicate). There is both verbal and non-verbal communication that occurs throughout our lives that have cultural and linguistic differences. These tend to develop within similar patterns and trajectories, regardless of where a child is in the world.

- Verbal: Speech. This includes articulation – making sounds become words – it is the act of talking.

- Non-verbal: This includes body language or non-verbal cues, social conventions, visual communication, tactile communication, and using various forms of language to make meaning of what others say.

- Internal language: Such as ‘private speech’, is also incredibly important for children when developing thinking, reasoning, processing and verbal skills. As contrast to social speech, private speech is not addressed to others, but to one’s self, as a source of self-guidance, self-regulation, focus, planning, motivating and monitoring the performance of tasks. This is typically seen in children from two to seven years old, but we often see this throughout life.

Watch

In the following 1-minute video you can see a 4-and-a-half-year-old child, Roxanne, narrating what she is doing, which is typical of how she does anything that she is deeply engaged in. This is an example of Piaget's Egocentric Speech / Vygotsky's Private Speech.

Watch

In the following 22-minute Ted talk video Dr. Brenda Fitzgerald is leveraging the simple practice of talking to babies and toddlers to nourish their brains and set them up for better performance in school and life:

Activity

Try to hold your tongue while speaking a sentence.

This should help to remind you that children are learning not only what words mean, as well as their structure, but also how to manipulate and pronounce words that we take for granted. They are also learning how to manoeuvre their mouths, tongues and lips to support the sounds required to make such words.

Check your understanding

Social development

This is the development of learning how to interact with others. As mentioned in language development, humans are a social species and rely on this to survive, hence why the attachment of an infant is so incredibly important. In fact, many argue that it is the most important element of development.

Social interactions are a give-and-receive system, especially during infancy, this is where they learn how interactions work. You may see a parent responding to the ‘coos’ of their baby as if they have understood their words, and then the baby responds again, this is ‘serve and return’; a term focusing on reciprocal, attentive, well-regulated interactions. This is attuned to the needs of the child, highly supporting the development of the brain for optimal growth and development. Serve and return is a concept important to remember throughout childhood and life.

Watch

In the following 5-minute video, you can see a mother having a conversation with her 3-month old infant (serve and return). In the video, you’ll see how the mother maintains eye contact with her child: eye contact is important for brain development and for emotional connection.

Does the child have your full attention? Are you actively listening to them? Are you taking the time to understand their needs and what they want to share? Prosocial skills include the development of caring behaviours, or those that will benefit others. You may see these through such demonstrations as empathy, sharing, kindness, helping, cooperating and putting your hand up to volunteer.

Social interactions vary through the development of children and begin with children ‘being’ together, which may not mean they are directly playing together, they may observe others and then eventually create cooperative relationships and friendships. Children learn most of their social skills through their environmental influences; those of the home, early childhood services, and schools. These may also be learnt through media exposure.

Children develop stages of play over time, starting by observing others play, displaying an interest in others and how they play, playing beside others, sharing materials with others and, eventually, interacting with others by playing the ‘same game’. They also will learn to play competitive play games. This will be discussed further in the next topic.

Watch

In the following 1-minute video, an educator explains how the educators in this centre purposefully create opportunities for peers to practise pro-social skills throughout the daily activities, which is important for children's social development.

When a baby makes eye contact with the primary caregiver, this is vital in early attachment and bonding. The special relationship it’s forming with the baby increases their sense of security and allows their brain to grow and develop on track. The more connected and attuned you are to the baby’s communication, the more you encourage their emotional development.

When a baby sees the primary caregiver’s eyes and face, they start to make connections between expressions and feelings (e.g. a smile means happiness). They learn how to respond and develop the ability to engage and relate to others, to regulate their own feelings, and communicate.

As the baby develops further and can follow your gaze, they will start to exchange information with you. This increases their ability to play and communicate, developing their language and vocabulary skills. This is seen when babies point to an object and their caregiver names it for them.1

Did you know?

- In the first few months of life, babies actually can’t see very well or long distances. This is why interacting with a baby when holding them close helps as they’re innately attuned to recognise the human face.

- Within the first 7 hours, newborns can have an intense interest in their mothers’ face, even mimicking facial expressions.

- Around 6 – 10 weeks babies will begin to direct their eyes intentionally, looking directly at you and holding your gaze with eyes widening.

- Usually, around 3 months of age, babies will follow movements if the primary caregiver is not too far away.

- It’s expected between 9 to 11 months, babies have developed the ability to follow eye gaze, showing they understand that eyes are meant for seeing and looking.

- At around 3 to 4 months of age, babies are able to smile deliberately at the primary caregiver when eye contact is made. This is called a social smile, and is them responding to another smile or trying to get that person to smile at them.

Note

If you feel that a baby is having a hard time making eye contact after 3 months of age, you could always refer the parents to a professional who will be able to evaluate the situation. A professional has the tools to check whether it is related to baby's eyesight, sensory processing capacities or other developmental issues.

NEVER DIAGNOSE A CHILD as this is a qualified health professional’s job and sharing assumptions with parents can cause unnecessary confusion.

Check your understanding

Biopsychosocial development

A term commonly used in health and also education to describe the interconnectedness between:

- The biology of a child (body make-up, genes, abilities, gender)

- Psychology of the child (personality, experiences, emotions, behaviours, memories, beliefs, cognitive/ emotional/social and intellectual capabilities)

- The social context of the child (supports, culture, family, education, social/economic status) and the impacts they have on children’s health, growth and development.

It is an important notion in understanding how the body is impacted, both negatively and positively, by these attributes as a whole. E.g. in recent times research has found that with ill children in hospitals it positively affected their health to have their family around them, and emotional support familiar to them. Previously, families were not allowed into hospitals with their sick children, as it was believed that a family could worsen the child’s ill health.

Watch

The following 2-minute trailer promotes a movie that simultaneously follows four babies around the world - from first breath to first steps. From Mongolia to Namibia to San Francisco to Tokyo, BABIES joyfully captures on film the earliest stages of the journey of humanity that are at once unique and universal to us all. The movie can be found on Netflix as well. You can find a few episodes of the ‘Babies’ 2004 documentary at the Additional Resources.

In the first thousand days of life, a child will make the most rapid developmental changes of their whole life. These profoundly affect the brain's structure, which takes on the form it will need to enable further growth throughout the child’s life. The brain at this time experiences an explosion of electrical and chemical activity, as billions of cells are organising themselves into networks requiring trillions of synapses between them. During these early years, their experiences and interactions influence the way a child’s brain develops, along with factors such as nutrition, good health and clean water. This will set a baseline for future success in school, and the character of adolescence and adulthood.

Watch

The following 2-minute video published by UNICEF summarises the first thousand days of a human’s life:

Check your understanding

Watch

The following 17-minute Ted Talk video, recorded in Namibia, explains the importance of a strong start in human life and its impact on the rest of our lives.

Did you know?

- Optimal development in the first 1000 days supports lifelong health, wellbeing and opportunity.

- Critical development happens from conception to 2 years - the first 1000 days.

- Children's brains and bodies are shaped by early experiences and environments.

In the first 1000 days, children need:

- Opportunities to learn through play

- Nutritious food

- Loving, responsive relationships

- Safe communities

- Toxin-free environments

- Green spaces

- Secure housing

In order to create a form of benchmark for children’s development, we also understand that although individual, children travel through fairly typical trajectories of development or milestone achievements.

There are many changes that occur in the early years, and as educators it is important to understand typical developmental expectations of children, in order to plan appropriate learning experiences for the child, provide a safe environment and meet their routine care needs. Understanding milestone development may also help to support families around any developmental concerns that may be observed.

The Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority (ACECQA) provide a quality document, combining developmental milestones, the approved learning framework in Australia and the national quality standards for the use of early childhood professionals. Learning frameworks guide early childhood teachers and educators in the design, delivery and evaluation of quality learning and development.

Resource

- Read about the developmental milestones for your child’s age group on ACECQA’s Starting Blocks website

- Download this booklet published by ACECQA to see major developmental milestones and how they link to the EYLF Outcomes and National Quality Standards.

- The Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) is a population-based measure of how children have developed by the time they start school. It looks at five areas of early childhood development: physical health and wellbeing, social competence, emotional maturity, language and cognitive skills (school-based), and communication skills and general knowledge. It also provides data about developmentally vulnerable children across Australia.

- Other reliable sources regarding child development:

Check your understanding

In order to plan appropriate learning experiences for the child, provide a safe environment and meet their routine care needs.

Check your understanding

Three (3) children from 3 different parts of the world are all learning skills at the same time, here are their experiences. Read the scenario, then answer the questions that follow. Review ACECQA’s milestone booklet to answer the questions.

Johnny is 3.5 years old; he uses the playdough to manipulate and mould into balls with his hands. He takes a small dish from the centre of the table and places the balls into the dish, counting them as he goes. He turns to Teena, his peer, who is sitting across from him, “would you like some ice-cream? It’s a sundae”. She agrees and pretends to eat the ice-cream with her hands. “Oh no, I nearly forgot, here is your spoon”, he laughs, “you can’t eat it with your hands!”

Sami is 3 years old; he helps his father to dig a trench in the yard as the water has been flooding towards their home. He uses a small shovel to help dig but mostly he collects sticks and leaves, creating a house on the top of the mound. He finds a small stick and threads a large leaf through it, “look dad, it’s a flag, they are celebrating their country at their house”, he begins to sing the national anthem.

Orlando is 2 years old; he uses a stick man his mother made him with wool and sticks, placing it into a small shallow box he found. He uses his finger as another character and the two begin to speak inside the box, “I need to go to the toilet” the finger puppet says, “that good you go to the toilet” the stick man answers, “ok, but don’t go anywhere ok, maybe can do some dancing when I come out”, “ok!” the other one says. The finger puppet jumps out of the box and goes to the toilet, Orlando makes ‘wee’ sounds. The puppet jumps back into the box, “ok, I’m ready for dancing!” The stick man and the finger puppet dance together inside the box.

Question:

For each child, which areas of development are they using and building on in the scenarios?

- physical/ fine motor development (i.e. manipulating playdough)

- cognitive development (i.e. counting, pretend play)

- social/emotional development (i.e. playing with a peer)

- language development (i.e. having a conversation with a peer)

Sami:

- physical/ gross motor development (i.e. digging a trench)

- social/emotional development (i.e. helping his father)

- cognitive development (i.e. creates a flag, sings anthem)

Orlando:

- language development (i.e. creating a dialogue for puppets)

- cognitive development (i.e. pretend play)

When we discussed the early development of the brain and ‘serve and return’ in previous readings, remember that these are both important elements to consider when discussing attachment. Attachment is the bond that an infant creates with another, usually the parent and usually first, the mother. This attachment is based on their emotional regulation needs and also a child’s feeling of safety, protection and care; organising the motivational, emotional, cognitive and memory processes according to the responses in meeting their needs. As an example, if an infant communicates (using infant cues such as crying), will someone respond and meet their needs? How are they made to feel safe and secure?

The quality of the attachment will impact a person’s mental health, future relationships and typically, all areas of development.

Watch

The following almost 3-minute video demonstrates the ‘still face experiment’. The video powerfully illustrates the importance of responsive interactions between mother/primary caregiver and child.

According to the Gottman Institute’s article, when we “still face” children by ignoring their expressions of emotion, they may experience a loss of agency for example. Show your child respect and understanding in moments when they feel misunderstood, upset, or frustrated. Validate their emotions and guide them with trust and affection. Children’s mastery of understanding and regulating their emotions will help them to succeed in life. Dr. Gottman calls this being an “Emotion Coach.”

The five (5) essential steps of emotion coaching are as follows:

- Be aware of the child’s emotion

- Recognize the child’s expression of emotion as an opportunity for intimacy and teaching

- Listen with empathy and validate the child’s feelings

- Help the child learn to label their emotions with words

- Set limits when you are helping a child to solve problems or deal with upsetting situations appropriately

Much like turning towards within a partnership, you can recognize the bids of children and respond to them to create and secure emotional connections. This means being interested in what they are saying or doing and listening to understand. Validate their feelings and emotions. Ask questions. Be the support they need.

Attachment theory

Attachment theory was coined by a theorist named John Bowlby (1969) and his student Mary Ainsworth (1989). They, along with other developmental theorists, developed linking behaviours and processes to attachment theory, including:

- Proximity seeking – when one yearns to be close to the attachment figure

- Distress when separated – when a child become visually upset when separated from the attachment figure

- Happiness at reunion – when the infant is visually pleased and excited by the return of the attachment figure

- Grief/sadness at loss – when an infant is upset and visually sad by the absence of the attachment figure

- Secure base – when the child feels confident to explore their world when their attachment figure is near, and can return to them as their ‘base’ as needed

- Confidence at the attachment’s commitment to the relationship – when the child acknowledges the attachment, and paired trust has been developed in line with their care and support

- Capacity for mutual enjoyment – when the infant and attachment share in joyous pursuits and interactions, such as peek-a-boo

- Preferred attachments and secondary attachments – children develop a preference for a particular attachment figure, but can also have a secondary attachment, which may include parent, grandparent, educator or other frequent caregivers.

The stages of attachment were henceforth moulded into four (4) stages.

- First stage (birth to five or six months): The infant in this stage is particularly responsive to the mother, as a preference; however, typically the child will be responsive to all responsive and caring carers who meet their needs

- Second stage (5–11 months): The baby shows a definite preference towards main carers and attachment figures

- Third stage (11–18 months): This stage is termed the separation anxiety stage, as the baby demonstrates distress when separated from main attachment figures, resisting the care or attention from unfamiliar people, if it means being separated from attachments

- Fourth stage (18–24 months): This is termed stranger anxiety. Young children in this stage will demonstrate a fear or extreme caution to strangers and unfamiliar people, often clinging to attachments or familiar people.

Types of attachment

Ainsworth identified three (3) main types of attachment and, later, a fourth style was added.

These types are:

- secure

- insecure (broken down into mistrust and avoidant)

- resistant/ambivalent, and

- disorganised.

Secure attachment (trust)

When a child is securely attached it means that they trust that their needs will be met. They are more open to those who are less familiar, though this may still take time, using the secure base concept as mentioned above, to return to the attachment when uncertain. They are able to express their needs and have expectations that their communication will lead to the desired result. It is essential for children to develop a secure attachment in order to feel supported and safe to explore their world and develop social relationships in life.

A secure attachment can also be a precursor to the emotional development and mental health of the child throughout life.

Insecure attachment (mistrust)

When a child is insecurely attached, they are less likely to express their needs, feeling uncertain that they will be met. This may form a dysregulation from being uncertain of how to respond to this emotionally, it may result in overexaggerated outbursts or diminished demonstrations of communicating needs to carer. This is when a child is either not responded to or not responded to in a supportive, caring manner, which may be inconsistent, harsh or negative.

This usually leaves a child confused and unsure about how to express their needs and whether their carer is trustworthy, resulting in high levels of separation anxiety, emotionally unsettled children, anxious, detached or clingy.

Watch

The following 7-minute video explains the importance of secure attachments in childhood:

Check your understanding

Read the following statements and decide whether they are TRUE or FALSE:

The terms of attachment have altered over the years, but typically include:

- Insecure avoidant: The child does not orientate, or rely, on the attachment figure for support, the child may be prematurely independent from the attachment figure and doesn’t seek their support. The attachment may be physically and emotionally unavailable to the child, without supporting and assisting their needs.

- Resistant/ambivalent: The child displays confused expectations or reactions to the attachment, they may appear overly clingy, but then react by rejecting or expressing anger towards the attachment at the time of interaction, especially if they have displayed what the child sees as an untrusting behaviour e.g. leaving the room and then returning. The child does not develop a sense of trust or security in the attachment figure, therefore finds managing their emotions difficult and confusing. The child due to inconsistent or nonresponsive caregiving is often difficult to calm and soothe when frustrated, afraid, angry or upset.

- Disorganised: This is often a style seen in vulnerable children who may have experienced abuse, witnessed abuse or domestic violence. It is a momentarily action of confusion as to how to respond in anxiety-provoking stations. They may become disconnected from the emotions of others, or even their own, responding to situations in a variety of disconnected ways, such as controlling, detaching, becoming distant, and they also struggle with resilience. The disorganised internal conflict is that, they want to be loved and belong, but also fear and mistrust close attachments, acting to ‘survive’.

Watch

The following 10-minute video explains how the connections from childhood impact the attachments in our adult life:

Use the following questions to check your knowledge. You can check the correct answer by clicking on the 'Answer' button:

- What are the potential impacts or influences on child development?

- Heredity

- Gender

- Physical attitudes

- Personality and temperament.

- Environment: geographic locations and the home environment

- Culture, religion and ethnicity

- Relationships and attachment

- Safety

- Nutrition

- Health and wellbeing

- Economics

- Politics and government

- How does child development occur?

Holistically, as an interconnection of social, psychological, environmental, and biological factors, including genetic factors that influence child and adolescent health and development. It also occurs both via cephalocaudal (head to toe) or proximodistal (from the centre, out) patterns.

- What is toxic stress?

When stress happens frequently, is ongoing, or is extreme, this becomes toxic stress, as the response system becomes constantly active, which is not healthy for development. The body becomes stuck in fight or flight mode, or most likely a state of hyper-vigilance, which is when the body is always prepared to have to survive through hyper-awareness or alertness.

- What are the major factors for brain development?

- A safe environment, where they are fed, kept warm and have good medical care

- Secure attachments with primary carers

- Safe environments for exploration and learning

- What are the concepts of motor development?

- Gross

- Fine

- Sensory

- What is the best attachment outcome according to attachment theory?

Secure attachment

- What is a critical period?

Critical periods are a class of sensitive period: that is, when elements of the nervous system require appropriate stimulation during a specific timeframe, in terms of behaviour, cognitive processing and psychological state and wellbeing.

- What is a sensitive period?

A sensitive period may last for months or years and is the timeframe where a developing child is particularly responsive to experience or particularly hindered by their absence in relation to the development of the brain.

- What is plasticity of the brain?

Plasticity is where a change to the brain and thinking can occur due to the experiences and influences it is presented with.