In this topic, we will explore effective infection prevention and control practices that support reduced risk of infection transmission between patients, healthcare workers and others in the healthcare environment. Employers and employee’s responsibility in infection control and prevention and strategies that can be implemented to prevent infections.

By the end of this topic, you will understand:

- The chain of infection and basis of infection

- Key modes of transmission, common infections in residential and home and community services environments

- Understand the risk of acquisition

- Identify key sources of infection

- Prevent the spread of infection

In all areas of health and community services work, you will need to understand the risk of infections and how they are transmitted to clients and workers. This is especially relevant since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. In all industries and across the whole Australian community, preventing and controlling infection is vital to the health and welfare of everyone. The clients you work with may have an increased vulnerability to infection, and you, as a worker, may also be at an increased risk of exposure to infections.

Definition of Infection

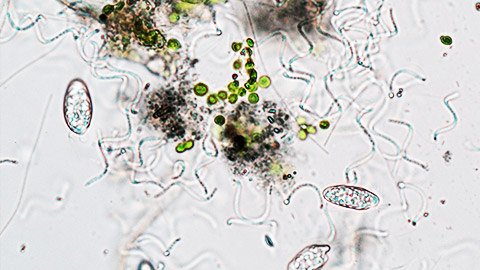

MedicineNet says that infection can be defined in medical terms as ‘the invasion and multiplication of microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses, and parasites that are not normally present within the body’. Infections can cause symptoms or not cause symptoms and can stay localised or spread throughout the body. Complying with infection control policies and procedures is an essential part of your job, and it is part of your duty of care towards your clients, colleagues and the community. You must have a good basic understanding of what infections are, how they are transmitted and what you can do to prevent and control their transmission.

The chain of infection

For an infection to occur, certain conditions must be in place. This is described as the chain of infection, and at any point in the chain, infection can be stopped by a link being broken.

The chain of infection comprises these six links:

- Infectious agent – the disease-causing pathogen.Infectious agents (pathogens) include not only bacteria but also viruses, fungi, and parasites. The degree of pathogens exposure depends on their number, their potency, their ability to enter and survive in the body, and the susceptibility of the host. For example, the smallpox virus is particularly virulent, infecting almost all people exposed. In contrast, the tuberculosis bacillus infects only a small number of people, usually people with weakened immune function, or those who are undernourished and living in crowded conditions.

- Reservoir – where the pathogen lives (e.g. in animals, medical equipment, water or people).A reservoir is any person, animal, arthropod, plant, soil or substance (or combination of these) in which an infectious agent normally lives and multiplies. The infectious agent depends on the reservoir for survival, where it can reproduce itself in such manner that it can be transmitted to a susceptible host. Animate reservoirs include people, insects, birds, and other animals. Inanimate reservoirs include soil, water, food, feces, intravenous fluid, and equipment.

- Portal of exit – the means by which the infectious agent leaves the reservoir (e.g. through sneezing, open wounds or aerosols). Portals of exit is the means by which a pathogen exits from a reservoir. For a human reservoir, the portal of exit can include blood, respiratory secretions, and anything exiting from the gastrointestinal or urinary tracts.

- Mode of transmission – how the infectious agent can be passed on (e.g. through inhalation or direct contact).Once a pathogen has exited the reservoir, it needs a mode of transmission to transfer itself into a host. This is accomplished by entering the host through a receptive portal of entry. The pathogen can be transmitted either directly or indirectly. Direct transmission requires close association with the infected host, but not necessarily physical contact. Indirect transmission requires a vector, such as an animal or insect Contact is the most frequent mode of transmission of health care associated infections and can be divided into: direct and indirect. Direct Contact(droplet and airborne): involves direct body surface to body surface contact and physical transfer of microorganism between an infected or colonized person to another person by touch. Transmission occurs when droplets containing microorganisms generated during coughing, sneezing and talking are propelled through the air. These microorganisms land on another person, entering that new person’s system through contact with his/her conjunctivae, nasal mucosa or mouth. These microorganisms are relatively large and travel only short distances (up to 6 feet/2 metres). Airbone transmission are also known as Aerosol transmission of infectious agents occurs either by: • Airborne droplet nuclei (small particles of 5 mm or smaller in size) • Dust particles containing infectious agents. Microoganisms carried in this manner remain suspended in the air for long periods of time and can be dispersed widely by air currents. Because of this, there is risk that all the air in a room may be contaminated This can occur from breathing, coughing, sneezing, or vocalization of an infected individual, but also during certain medical procedures (e.g., suctioning, bronchoscopy, dentistry, inhalation anesthesia. Indirect contact includes both vehicle-borne and vector borne contact. A vehicle is an inanimate go-between, an intermediary between the portal of exit from the reservoir and the portal of entry to the host. Inanimate objects such as cooking or eating utensils, handkerchiefs and tissues, soiled laundry, doorknobs and handles, and surgical instruments and dressings are common vehicles that can transmit infection. Blood, serum, plasma, water, food, and milk also serve as vehicles. For example, food can be contaminated by E.coli if food handlers do not practice appropriate handwashing techniques after using the bathroom. If the food is eaten by a susceptible host, such as a young child or a person with HIV/AIDS, the resulting infection can be life-threatening. Vector-borne contact is transmission by an animate intermediary, an animal, insect, or parasite that transports the pathogen from reservoir to host. Transmission takes place when the vector injects salivary fluid by biting the host, or deposits feces or eggs in a break in the skin. Mosquitoes are vectors for malaria and West Nile virus. Rodents can be vectors for hantavirus.

- Portal of entry – the means by which the infectious agent can enter a new host (e.g. through the respiratory tract or broken skin). Infectious agents get into the body through various portals of entry, including the mucous membranes, non-intact skin, and the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary tracts. Pathogens often enter the body of the host through the same route they exited the reservoir, e.g., airborne pathogens from one person’s sneeze can enter through the nose of another person.

- Susceptible host – a person who may be at risk of infection (in many cases, this can be any individual. Entry of the pathogen can take place in a future host (ie the person who is next exposed to the pathogen). The microorganism may spread to another person but does not develop into an infection if the person’s immune system can fight it off. They may however become a ‘carrier’ without symptoms, able to then be the next ‘mode of transmission’ to another ‘susceptible host’. Once the host is infected, he/she may become a reservoir for future transmission of the disease.

Watch the following videos for more information about how the chain of infection works.

Basis of infection

Pathogens are the basis of Infection. Infectious diseases are caused by harmful microorganisms called pathogens. Pathogens include viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites. There are also harmless microorganisms present in the environment and in our biological systems. For example, there are benign bacteria that live in our gut, which do not cause illness or disease. However, pathogens – the microorganisms that cause harm – are the basis of infectious disease. Pathogens may be transmitted by other people, animals or environmental sources, such as water. How a pathogen is transmitted depends on the pathogen. There are many different factors that affect the risk of acquiring infection. These factors include the characteristics of the person exposed to infection, such as their immune status, the type of infecting organism and features of the environment such as cleanliness and density of population, sources of infection and means of transmission.

There are reservoirs that also become the basis for spread of infection: Blood or bodily fluids- Some infections are spread when body fluids such as blood, saliva come into direct contact with an uninfected person through kissing, sexual contact or through a needlestick injury. For example contaminated substances can enter the body through break in skin which can infect the person. People who are actually ill People who are actually ill are infectious hence its called the Infectious period it is the time during which a person is contagious and able to transmit an infection to other people Food, water and soil-touching contaminated food or eating contaminated food – the pathogens in a person's faeces may be spread to food or other objects, if their hands are dirty Waste-Most of the waste materials contains blood, bodily fluids, and tissue of patients and these substances may contain infectious microorganisms that have the potential to transmit disease and thus require proper management and disposal. Patients with known infections are likely to generate waste containing a large amount of microorganisms for example the sputum of a patient with known TB, the syringe used on a patient with known HIV or viral hepatitis, a diaper with the stool of a baby admitted with diarrhea, are all examples of infectious waste with the potential to transmit disease. Penetrating injuries-Penetrating injury is an injury caused by a foreign object piercing the skin, which damages the underlying tissues and results in an open wound Skin penetrating injuries can introduce infectious agents directly into the blood stream, e.g. tetanus and blood borne viruses such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV. Infection through vectors(animal, insect or parasite)-Vector-borne diseases are infections transmitted by the bite of infected arthropod species, such as mosquitoes, ticks, triatomine bugs, sandflies, and blackflies. Arthropod vectors are cold-blooded (ectothermic) and thus especially sensitive to climatic factors. Examples of vector-borne diseases include Dengue fever, West Nile Virus, Lyme disease, and malaria.

Infecting microorganisms may be present:

- In carriers – Carriers are people who carry the infecting organism in their bodies, whether they are affected by symptoms of the disease or not. Some people carry the infecting organism but do not have the disease. For example, in the 19th century, a woman called ‘Typhoid Mary’ infected many people around her with typhoid and was found to be carrying the bacteria that caused typhoid although she had no symptoms herself.

- During the incubation phase – The incubation phase is the period of time after a person has been exposed to the source of infection and has acquired the infection but before any symptoms appear.

- In people who are acutely ill – Infections can be transmitted after the person acquires the infection, develops symptoms and becomes acutely ill. Infection prevention and control aims to limit or stop the spread of pathogens by either presenting a barrier to transmission, for example, by using PPE, or by killing the pathogen, for example, by using alcohol-based sanitisers and disinfectants.

For an overview of the basis of infection, pathogens and methods of preventing transmission, read: ‘Infectious Diseases: How Do You Break the Chain?’ from Ausmed.

Colonisation, Infection and Disease

‘Colonisation’ means that germs or pathogens are present in or on your body but they do not make you sick, so you have no symptoms of the disease and you do not feel ill.

‘Infection’ means that germs or pathogens are present in your body and they do make you sick, resulting in you showing symptoms, for example, a fever, a high white blood cell count, pus from a wound or inflammation. Because an infected person shows symptoms, it is more likely they will be tested and identified as being capable of transmitting the infection to others.

‘Disease’ means that the infection has resulted in damage to your body. A person typically develops disease after feeling ill from an infection for a period of time.

How to Tell Who Is Infected

Without testing a person for a specific infection, it is not possible to tell whether they are capable of transmitting the pathogen they carry to other people. This means that people who are colonised present a community and public health risk. People who have been colonised by a pathogen are said to be ‘incubating’ the disease, although not all of them will develop symptoms, feel ill or be affected by the disease. An infected person usually shows symptoms, so it is likely that a symptomatic person will be tested and identified as being capable of transmitting the infection to others. Infected people present risks to others and are very likely to show symptoms and be identified when they are acutely ill. Some people are said to be ‘carriers’ of a disease. This means that, although they are not affected themselves, they are capable of passing it on to others.

In health and community care work it is important to know whether or not a person is carrying an infection so that measures can be taken to prevent its spread to others, Resource especially when working in services for vulnerable groups.

Watch the following short video: ‘Colonization Versus Infection: Why the Difference Is Important in Nursing Home Care’ by Infection Project

Fungi, Viruses, Bacteria and Bacterial Spores

Organisms and microorganisms can be either harmful or benign. Those that are harmful are called ‘pathogens’ and can cause infection and disease. The pathogens we will focus on in this resource are fungi, viruses, bacteria and bacterial spores.

Fungi

There are millions of different kinds of fungi, ranging from single-celled to complex organisms, so there is no definitive way of preventing fungal infections. However, fungal infections commonly affect the skin and are most commonly transmitted by contact.

This means basic precautions are relatively straightforward, including:

- Keeping skin clean and dry

- Changing clothing frequently (such as underwear, shoes and socks)

- Not sharing towels, bedlinen or clothing

Viruses

Viruses are microscopic parasites that are usually much smaller than a fungus or bacterium (‘bacterium’ is the single form of the word ‘bacteria’: one bacterium, many bacteria).Viruses are not able to thrive and reproduce outside of a host body. This means that, when a virus infects a cell, the cell usually dies and is replaced by a virus-infected cell, which then infects other cells. Viruses are considered to be ‘non-living’ life forms and are usually infectious agents. All of the planet’s life forms are susceptible to viruses.

Bacteria

Live Science defines bacteria as ‘microscopic, single celled organisms that thrive in diverse environments’. Live Science explains that bacteria can live in soil, the ocean and inside the human gut, and that humans’ relationship with bacteria is complex. Sometimes bacteria can be extremely useful to us, such as its use in making yogurt and ability to help with our digestion, but bacteria can also cause infections that lead to serious disease. Unlike viruses, bacteria are living cells and do not need a host organism to reproduce.

Bacterial Spores

Bacterial spores are dormant forms of bacteria that can survive harsh environmental conditions. The spores allow the bacteria to regenerate when conditions become less harsh. Bacterial spores are highly infectious. Once inside a host, the spores can germinate and become active, potentially resulting in the host becoming infected and developing a disease.

For a good discussion on how viruses spread, watch ‘What Is a Virus? How Do They Spread? How Do They Make Us Sick?’ from The Conversation.

The more often you are exposed to a source of infection and the fewer precautions you take, the more likely you are to become infected. The more pathogens and people within an environment, the more likely it is that infections will be transmitted. With life-threatening infections, the consequences of mass transmission can be catastrophic. This is what many are experiencing with COVID-19. Risks of acquiring an infection or disease depend on factors such as the frequency of exposure, modes of transmission, type of pathogen, proximity to infected people, environmental factors, precautions and preventive measures used, and the vulnerability or susceptibility of people exposed to the infection.

Key Modes of Transmission

Watch this video below on pathogens and transmission of disease.

There are several modes for the general transmission of pathogens.

The three key modes are:

- Direct contact

- Airborne

- Penetrating injuries

There are five main modes for transmission of microorganisms in animals and humans:

- Direct contact

- Fomites (materials or objects likely to carry infection)

- Aerosols (airborne transmission)

- Oral (transmission via ingestion)

- Vector borne (transmission via insects and other small organisms).

Some microorganisms can be transmitted by more than one route. Direct Contact ‘Direct contact’ means touching something or somebody infected with a pathogen. Washing or sanitising after you have contact with a contaminated object or person, or using a barrier such as wearing gloves, are the key ways to prevent transmission of infection through direct contact. A direct-contact infection can occur through a single instance of contact with a microscopic source of infection.

Airborne

‘Airborne transmission’ means that the pathogen is spread through either droplets or aerosols. Droplets are tiny drops of moisture or fluid that contain the pathogen, and aerosols are tiny particles suspended in the air.

Airborne transmission includes sneezing, coughing and any action that involves exhaling. With airborne transmission, the closer you are to the person and the longer the time you are near them, the more likely it is that transmission will occur. Nevertheless, infection can occur with just one sneeze or cough and with only passing or very brief exposure. Maintaining distance from other people and using barriers such as masks can prevent airborne transmission. Similarly, hygiene practices around coughing or sneezing, such as covering the mouth, disposing of tissues and washing hands after contact with potentially infectious surfaces and materials, can also prevent airborne transmissions.

Penetrating Injuries

Penetrating injuries occur when the skin is broken or penetrated. Cuts, grazes and stab injuries from sharp objects are referred to as ‘penetrating injuries’. Following procedures for the proper handling and disposing of sharp objects can help you prevent infection. Sharp objects can include hypodermic syringes, knives and scissors.

Factors That Increase Susceptibility to Infection

Several factors increase an individual’s susceptibility to infection, including:

- A compromised immune status

- A wound or medical device that penetrates the skin

- Medications

- Comorbidities

- Age

- Certain environmental factors A group of people who share one or more of these factors is classified as a ‘vulnerable group’.

- Immune Status Our immune system includes all the ways in which our body responds to and fights against infection. If any of the immune system’s components are damaged, weakened or not functioning correctly, the immune status of the person is said to be ‘compromised’, which means that it does not defend the person against infection as well as it should and the person will be more susceptible to infection. A person’s ‘immune status’ refers to how well their immune responses are working.

Watch the following videos on how infections are transmitted.

Watch, the following videos on how Pandemics spread.

Activity

Read the case study below and answer the questions that follow:

Mary and Sam Mary is in her 80s. She lives in her own home with her son Sam, who is in his 50s. Sam has spina bifida and uses a wheelchair. He has a colostomy and a shunt in his head to relieve a build-up of fluid. Mary has diabetes and has lost some of her eyesight. She has also been diagnosed with coronary heart disease and she has frequent urinary tract infections. Support workers come into their home each day to help with household chores and the cleaning and shopping. Sam has personal-care support workers who come in each morning to help him shower and dress. They also come each evening to help Sam prepare for bed. There is a visiting nurse who checks Sam’s colostomy, the opening in his spinal neural tube and his shunt. Mary and Sam are First Australians. They have a large extended family and are regularly in contact with them. There are usually several family members staying with Mary and Sam. The family members help with shopping, cleaning and cooking.

- How many risk factors can you identify that would make Mary and Sam more susceptible to infection?

- Identify the potential impact of each factor you have detected on Mary’s and Sam’s immune system.

- Identify the potential impact of each factor you have detected on Mary’s and Sam’s general, physical and mental health.

Some infections can be especially common—and dangerous—in residential settings where a number of people live and work together. They can be easily spread through performing close tasks like personal care. Older people and people with disabilities, especially those with chronic health conditions, can catch some infections more easily, and they can be more dangerous in these people, too.

Below is a table on most common types of infections in care homes.

Types of infection outbreaks

| Types of infection outbreaks | Most common causative infectious agents | Mode of transmission |

|---|---|---|

| Respiratory infection | Influenza virus (A or B) | Droplets and physical contact |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Airborne infection | |

| Skin and soft tissue infection | Streptococcus pyogenes | Droplets and physical contact |

| Staphylococcus aureus (sensitive or resistant) | Physical contact and airborne dissemination | |

| Sarcoptes scabei (the mite causing scables) | Physical contact | |

| UTI (with or without a urinary catheter)* |

Escherichia coli, many MDRO's |

Physical contact (transmission will have taken place sometime before the organism cause a UTI) |

| Gastrointestinal infections | Norovirus, Salmonella and other organisms causing food poisoning | Physical contact with contaminated items followed by ingestion** or direct ingestion of contaminated food |

| Clostridium difficile | Physical contact with contaminated items followed by ingestion | |

|

Key: MDRO = multidrug-resistant organism; MRSA = methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; UTI = urinary tract infection. |

||

Activity

Research one particular transmissible infection that might be commonly seen in a community services workplace. You might use one of the examples above, or another of your choosing. Find out:

- How is the infection carried from one person to another?

- How long does it usually take for a person to become ill after contact with the infection?

- How long is the person infectious for, and what are the critical times for when it can be passed on to others?

- What are the signs and symptoms of the condition?

- What precautions would help prevent the spread of the condition?

Watch the following video on common infections in aged care.

In all health and community services settings, using measures to prevent and control the spread of infection is essential. This is especially important in residential settings and remote communities. In residential settings, vulnerable clients are living together, and support workers are circulating among them, perhaps working across different sites, and in remote community settings, residents live in close contact with each other. Settings like these have the potential to become hot spots for infections unless prevention and control procedures are followed stringently.

What is prevention and control of infection?

It is important to understand the difference between the prevention and the control of infection:

- ‘Prevention’ means stopping an infection from being transmitted and stopping a disease from harming people.

- ‘Control’ means limiting or minimising the spread of infection and limiting the harm it does to people.

Infection prevention and infection control aim to minimise and prevent the spread of infection. Preventing, controlling and minimising infection are crucial actions in health and community services work, particularly in residential settings where a large number of people live and work together and are in close day-to-day contact with each other. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, society as a whole has become more aware of the need to have and follow effective infection control procedures. The need to protect yourself and others became a community responsibility from March 2020 in Australia because coronavirus affected everyone’s wellbeing. Measures like social distancing, separating vulnerable people from other groups, isolating infected or potentially infected people and adopting strict hygiene measures, such as frequent handwashing, were established as everyday occurrences.

The Australian Guidelines for the prevention and control of infection in healthcare is a nationally accepted approach to infection prevention and control. The guidelines focus on core principles of infection control and outline priority areas for health services. The routine work practises outlined in the Guidelines for Infection Control are designed to reduce the number of infectious agents in the work environment; prevent or reduce the likelihood of transmission of these infectious agents from one person or item/location to another; and guidelines to make areas as free as possible from infectious agents.

here is the link to the Australian Guidelines for infection control and prevention https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/infection-control-guidelines-feb2020.pdf

Common types of infectious risk in work environment and ways to prevent and reduce harm.

Risk of sustaining injury through sharps 1. If exposed to sharp injury ensure to disinfect and wash your hands 2. use personal protective equipment where appropriate use gloves, protective clothing, and other protective equipment when necessary 3. remove or isolate the hazard by using sharps disposal containers 4. handle needles and sharp objects safely 5. attend education and training on the correct use of medical devices incorporating sharps protection mechanisms including demonstrated competent use of the device

Risk of coming in contact with people who have an increased prevalence of having an infectious disease; 1. Thoroughly wash hands with water and soap for at least 15 seconds after visiting the toilet, before preparing food, and after touching clients or equipment. Dry hands with disposable paper towels 2. Cover any cuts or abrasions with a waterproof dressing to stop the spread of infection. 3. wear gloves when handling body fluids or equipment containing body fluids, when touching someone else's broken skin or mucus membrane, or performing any other invasive procedure. 4. Wash hands between each client and use fresh gloves for each client where necessary 5. don't share towels, clothing, razors, toothbrushes, shavers or other personal items.

working in an area in which a potentially infectious organism is endemic or where there is an outbreak of infection. 1. maintaining good hand hygiene and using hand disinfectant (hand sanitizer) 2. not touching face with your hands if there are higher chances of being exposed to the infection 3. having good cleaning routines in the workplace 4. equipping and organising the workplace to prevent infection 5. using safety gloves if the risk assessment shows it is necessary.

contact with animals that have an increased prevalence of having an infectious disease 1. Use appropriate insect repellent. 2. practise good hand hygiene. Thorough hand washing after handling any potential source of infection is also necessary. 3. use personal protective equipment (PPE) when needed. 4. Wear protective clothing and wearing gloves when handling animals or their tissues, taking care not to rub the face with contaminated hands or gloves. 5. Get vaccinated against tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBE).

Standard and Transmission Based Precautions

Infection prevention and control uses a risk management approach to minimise or prevent the transmission of infection. The two-tiered approach of standard and transmission-based precautions provides a high level of protection to patients, healthcare workers and other people in healthcare settings. Standard Precautions Standard precautions are those that must be used routinely to prevent and control the transmission of any infection. Standard precautions are the minimum that must be expected at all times.

Standard precautions include:

- Hand hygiene

- The use of PPE

- Environmental control

Transmission-Based Precautions

Additional precautions to standard measures are used when there is a specific threat, such as when there is the presence of a highly infectious or contagious condition that cannot be contained by standard precautions alone, for example, outbreaks of diseases like measles, chicken pox or the flu; and pandemics like COVID-19. Transmission-based precautions are used for patients who are known to be, or who may be, infected with highly transmissible infection-causing pathogens. The type of precautions put in place depend on the route of transmission.

Transmission-based precautions include wearing:

- Gloves

- A P2 respirator

- A surgical-style mask

Additional precautions do not replace standard precautions. Standard precautions must continue to be used alongside transmission-based precautions

Lets look at the standards and additional precautions in detail now.

Hand Hygiene

Hand hygiene is one of the first lines of defence for preventing and controlling the spread of infection. It is a standard precaution and should be used routinely in any situation that may present a risk of transmission. You can explore the following link for authoritative and more detailed instructions about hand hygiene: ‘Hand Hygiene’ from the Government of South Australia’s SA Health

Hand Hygiene includes the following:

Hand Care

It is important to keep your skin and fingernails intact and to avoid contaminating jewellery such as rings, watches and bracelets. The easiest way to do this is not to wear jewellery on your hands. Most hand hygiene policies and procedures prohibit the wearing of jewellery. Using hand creams to prevent chafing and cracking and keeping fingernails clean, trimmed and undamaged also contributes to hand hygiene. Hand hygiene and hand care should be carried out in relation to all activities involving client interactions, including ‘non-clinical moments’, which are times when activities not related to clinical care are being carried out.

Hand Washing

Use soap and water to wash your hands before you touch anything so that you do not contaminate anything in your surroundings. Also use soap and water to wash your hands after touching anything that might be contaminated. All workers in health and community work settings must follow this procedure, especially as part of preventing and controlling the spread of COVID-19. (Remember that you should do this at home as well as at work.) Before you wash your hands, take off your rings, jewellery and/or wristwatch and make sure that any cuts or abrasions on your hands are covered with waterproof dressings. Knowing When to Wash Your Hands Wash your hands with soap and water whenever they become or might become soiled, for example, after assisting a client with toileting, changing continence pads, cleaning up spills, handling contaminated materials such as dirty linen or clothing, wiping down surfaces or carrying out other cleaning tasks.

Watch this YouTube video by Johns Hopkins Medicine to see how to wash your hands thoroughly: ‘Hand-Washing Steps Using the WHO Technique’.

Using Hand Sanitisers

Rubbing your hands with alcohol-based hand sanitiser is a good alternative to washing your hands when soapand-water washing is not readily available. This applies to when your hands are visibly dirty and also when they are not visibly dirty. The Surgical Scrub Technique The surgical-scrub handwashing technique is used before undertaking any surgical procedure. In an aged care or disability work setting, this may include before administering first aid such as dressing a wound or changing a dressing.

Watch this video on using hand sanitisers effectively.

Click here for more information on Alcohol - Based Handrubs

Hand Hygiene technique includes: 1. Wet your hands with warm water. 2. Apply one dose of liquid soap and lather (wash) well for 15–20 seconds (or longer if the dirt is ingrained). 3. Rub hands together rapidly across all surfaces of your hands and wrists to help remove dirt and germs. 4. Don’t forget the backs of your hands, your wrists, between your fingers and under your fingernails. 5. If possible, remove rings and watches before you wash your hands, or ensure you move the rings to wash under them, as microorganisms can exist under them 6. Rinse well under running water and make sure all traces of soap are removed, as residues may cause irritation. 7. Pat your hands dry using paper towels (or single-use cloth towels). Make sure your hands are thoroughly dry. 8. Dry under any rings you wear, as they can be a source of future contamination if they remain moist. 9. Hot air driers can be used but, again, you should ensure your hands are thoroughly dry.

Five precautions you need to take when there is break in skin or skin conditions: 1) cover visible skin lesions (eg. cuts, abrasions, and/or infections) on exposed parts of your body with an adhesive water-resistant dressing. Change the covering regularly or when the dressing becomes soiled 2) Taking proper hand care is important as a means of preventing rashes and lesions, because intact skin is a natural defence against infection 3) before using hand cream under gloves, check the label to see whether it is oilbased or aqueous. 4) Use Aqueous-based hand creams and Oil-based preparations should be avoided as they may cause latex gloves to deteriorate 5) wear gloves whenever the skin of the hand is grazed, torn, cracked or broken (wearing gloves does not eliminate the need for hand washing

How do you identify circumstances when hand hygiene is required to be followed: 1. immediately before attending to any client 2. before putting on and after removing gloves 3. after contact with blood or other body substances 4. after contact with used instruments, jewellery and surfaces contaminated with (or which may have been contaminated with) blood and body substances 5. before contact with instruments that penetrate the skin 6. after other activities which may cause contamination of the hands and forearms, eg. smoking, eating, using the toilet, touching part of your body whilst performing a procedure 7. before a skin penetration procedure is undertaken, and whenever an operator leaves the procedure area and then returns to resume the procedure 8. whenever hands are visibly soiled 9. in any other circumstances when infection risks are apparent

How to identify correct Hand Hygiene Product

1.relative efficacy of antiseptic agents and consideration for selection of products for hygienic hand antisepsis and surgical hand preparation; 2.dermal tolerance and skin reactions; 3.product cost 4.aesthetic preferences of Health care workers and patients such as fragrance, colour, texture, “stickiness”, and ease of use; 5.practical considerations such as availability, convenience and functioning of dispenser, and ability to prevent contamination; 6.time for drying (consider that different products are associated with different drying times; products that require longer drying times may affect hand hygiene best practice)

Things to remember five 5 clinical moments of when and why hand hygiene should be performed

Moment When? Why? Before touching a patient-Clean your hands before touching a patient when approaching him/ her.To protect the patient against harmful germs carried on your hands. Before clean/aseptic procedure-Clean your hands immediately before performing a clean/aseptic procedure.To protect the patient against harmful germs, including the patient's own, from entering his/her body. After body fluid exposure risk- Clean your hands immediately after an exposure risk to body fluids (and after glove removal). To protect yourself and the health-care environment from harmful patient germs. After touching a patient-Clean your hands after touching a patient and her/his immediate surroundings, when leaving the patient’s side. To protect yourself and the health-care environment from harmful patient germs. After touching patient surroundings-Clean your hands after touching any object or furniture in the patient’s immediate surroundings, when leaving – even if the patient has not been touched. To protect yourself and the health-care environment from harmful patient germs.

The Surgical Scrub Technique

The surgical-scrub handwashing technique is used before undertaking any surgical procedure. In an aged care or disability work setting, this may include before administering first aid such as dressing a wound or changing a dressing.

Watch the following video for instructions on how to do a surgical scrub: ‘How to Wash Your Hands for Surgery’ by Surgical Tech Tips

Hand-hygiene case study

Read the following case study and answer the questions at the end.

Tabitha is a support worker in a disability service that provides in-home support for people with disabilities. Tabitha has several clients who have limited mobility and high support needs. Two of these clients live in a purpose-built residence, and the third lives with his family. Tabitha visits these clients daily to assist with dressing, bathing, toileting, food preparation and mealtimes. She has a 40-minute drive between the two residences and is often late and running short on time. Within the purpose-built residence there are hand sanitisers near the front door and in the laundry, the kitchen and each bathroom and bedroom. There are also soap dispensers in the laundry and next to each sink and bathroom basin, and posters hang around the residence reminding everyone to wash or sanitise their hands. In the third client’s family home, there is one handsanitiser dispenser in the client’s bedroom and hand soaps in the bathroom. Yesterday Tabitha had to clean up a spill of urine in the home-based client’s bathroom. She cleaned it with a mop and water but could not find any disinfectant or floor detergent. Tabitha was in a hurry, so she asked the client’s mother to follow up by washing the whole floor later. Tabitha then visited the group home, where she assisted one of the clients to dress a small cut with Band-Aids. She then prepared the evening meal.

- In which of these environments is infection more likely to be transmitted? Why?

- At which points should Tabitha have washed her hands with soap and water? Why?

- At which points should Tabitha have used sanitiser to clean her hands? Why?

- At which point was Tabitha most likely to transmit an infection? Why?

Respiratory Hygiene

Many pathogens are carried in the droplets we expel when we cough or sneeze, and others are carried as airborne particles. Mucus can also carry pathogens. Respiratory hygiene and etiquette means covering your mouth and turning away from other people when you cough or sneeze. It is a precaution we should use routinely to prevent spreading infection as well as to be polite. If you do not have a tissue, you can cough or sneeze into your elbow. Avoid touching your mouth and face after you cough or sneeze. You should also use disposable tissues rather than cloth handkerchiefs and wash your hands or use hand sanitiser as soon as possible after you cough or sneeze.

To learn more about cough etiquette: visit ‘Questions and Answers: Cough Etiquette’ from the Government of South Australia’s SA Health

Personal Protective Equipment

Protective equipment is clothing or equipment designed to protect the wearer from the risk of injury or illness. It can include protective hearing devices (e.g. ear muffs and ear plugs), hand protection (e.g. gloves), respiratory protective equipment (e.g. masks), and eye and face protection (e.g. safety glasses and face shields).

In health and community work, the PPE most often used is face masks, gloves, waterproof aprons or gowns, and sometimes face or eye shields. Awareness of the use of PPE in healthcare and allied settings has increased since the COVID-19 pandemic began, but gloves and aprons, especially in residential settings in aged care and disability sectors, have always been used.

The aim of PPE is to present a barrier to the transmission of infection. To achieve this, PPE must be used correctly. You must always follow the relevant guidelines for any protective equipment. You will need to regularly check media sources and announcements relating to updates and developments for health measures for the general community and for your community care sector.

The following is a summary of PPE used in aged care and disability work settings by support workers:

Equipment Rules for Use:

Gloves

Use gloves whenever you are handling or touching potentially infected surfaces, materials, objects or people, especially if handling blood or body fluids and as part of transmission-based precautions. Change your gloves in between contact with different people and during contact with the same person if there is a risk of cross contamination between parts of the body (e.g. after changing a dressing). Wash or sanitise your hands before and after you use gloves.

There are four general categories of gloves:

1. Work gloves (leather, metal, canvas

2. Fabric and coated gloves (cotton/other fabric, cotton-coated with plastic)

3. Chemical-resistant/liquid-resistant gloves (butyl rubber, natural latex, neoprene, nitrile rubber)

4. Insulating rubber (for electrical protective work)

Gloves are divided into three Grades:

1. Minimal risk: These are commonly known as disposable gloves they are simple and designed for hygiene, comfort or to protect against risks, the effects of which are easily reversible or have no consequence to the health of the user.

2. Medium risk: These gloves protect against risks which can result in permanent adverse health effects. These protective gloves are tested according to the Australian standards by an accredited laboratory. The range of protective gloves in this category is extremely wide. These protective gloves often consist of multi-layer structure, of different materials, sometimes very sophisticated, to meet all work-related requirements. These protective gloves protect against cuts, abrasion, burns, chemicals, infectious agents, radioactive contamination.

3. These gloves are of very complex design to protect against irreversible damages to health. These gloves must not only have passed the test of the 2nd category, but has also to be subjected to a product quality assurance system. These protective gloves are very specific, e.g. for fire fighters, founders, butchers, electricians or employees of the chemical industry. They protect against burns due to flames or splashes of molten metal, deep cuts, electrical high tension, burns and poisoning by chemicals.

TECHNIQUE TO APPLY,FIT and REMOVE GLOVES

1. Thoroughly wash hands.

2. Select the appropriately sized gloves.

3. Hold with one hand and Insert the other. When the base of your thumb reaches the cuff of the glove, begin to spread fingers and insert hand into a glove.

4. Pull glove cuff towards wrist to cover as much skin as possible and secure glove.

5. Check to make sure there are no holes or tears.

6. Repeat steps 3-5 for your other hand.

Remove gloves

- Outside of gloves are contaminated? If your hands get contaminated during glove removal, immediately wash your hands or use an alcohol-based hand sanitiser

- Using a gloved hand, grasp the palm area of the other gloved hand and peel off first glove

- Hold removed glove in gloved hand

- Slide fingers of ungloved hand under remaining glove at wrist and peel off second glove over first glove

- Discard gloves in a waste container

- Gloves NEVER replace hand hygiene.

- DO NOT wash and re-use gloves.

- Change and discard single-use gloves: – After each contact – After each task – Before starting another task

Protective eye wear and face shields

Protective glasses and face shields can be used as part of PPE in healthcare and community services settings. Follow appropriate guidelines on the correct use of protective glasses, and ensure that you wash your hands after removing them from your face

Goggles with a manufacturer’s anti-fog coating provide reliable, practical eye protection from splashes, sprays, and respiratory droplets from multiple angles. Newer styles of goggles fit adequately over prescription glasses with minimal gaps (to be efficacious, goggles must fit snugly, particularly from the corners of the eye across the brow). Other types of protective eyewear include safety glasses with side-shield protection, which are widely used in dentistry and other specialties that use operating microscopes. While effective as eye protection, goggles and safety glasses do not provide splash or spray protection to other parts of the face. Personal eyeglasses and contact lenses are not considered adequate eye protection

Technique to Apply, Fit and remove eyewear

- Check if safety glasses comply with the ANSI Z87.1 eye protection standard.

- Ensure that there are no cracks or deformities on the lenses.

- Ensure the strap is in good working condition and is firmly sealed to the cheek and forehead.

- Clean and disinfect after use.

- REMOVE: Outside of goggles or face shield are contaminated!

- If your hands get contaminated during goggle or face shield removal, immediately wash your hands or use an alcohol-based hand sanitiser

- Remove goggles or face shield from the back by lifting head band and without touching the front of the goggles or face shield

- If the item is reusable, place in designated receptacle for reprocessing. Otherwise, discard in a waste container

- This equipment must be worn when there is potential for splashing or spraying of blood and other body substances.

- This equipment may be re-usable or single use.

Note: Your own prescription spectacles are not protective eye wear.

Masks

In the context of COVID-19 and similar airborne infections, non-medical-grade face masks can prevent an infected person from spreading the infection. They may also provide a degree of protection for the wearer against contracting an infection. Medical-grade face masks are designed to protect wearers against acquiring an infection as well as preventing the spread of infection. It is important to use face masks correctly. If you touch your mask once, it has potentially become infected and you risk spreading the infection as well as contracting it yourself. Always wash your hands after removing and disposing of a face mask.

Technique to fit, apply and remove masks

1. Wash or sanitize hands before wearing the mask

2. Check the mask for damages

3. Ensure the colored-side faces outwards

4. Cover the mouth, nose, and chin and adjust accordingly without leaving gaps on the side

5. Ensure you can breathe properly while wearing a mask

6. Avoid touching the mask while using it

7. Wash or sanitize hands before removing the mask

8. Remove the mask by the strap behind the ears

9. Wash the mask preferably with soap and hot water at least once a day

10. Dispose of the mask properly after use Removing Mask Front of mask/respirator is contaminated — DO NOT TOUCH!

•If your hands get contaminated during mask/respirator removal, immediately wash your hands or use an alcohol-based hand sanitiser

•Grasp bottom ties or elastics of the mask/respirator, then the ones at the top, and remove without touching the front

•Discard in a waste container

- Masks must be fitted and worn correctly to cover your nose and mouth.

- Do not touch your mask while wearing it.

- Remove the mask if it is moist or soiled.

- DO NOT wear your mask around your neck.

Gowns and plastic aprons

Gowns and waterproof aprons can be used to protect a worker’s clothes from spills and splashes. They can also be used when a worker is in areas that may be contaminated or is dealing with contaminated materials. Soft shoe coverings can be worn to reduce the spread of contamination and infection. Depending on the work setting, these kinds of PPE may be disposable (single use) or washable and re-usable.

Technique to fit, apply and remove gowns

1.Ensure the gown is sized properly, and large enough to allow unrestricted freedom of movement.

2.Tie the gown securely but in a manner that it can be easily untied when you begin the doffing process Leave some length of the tie so that it can be pulled and untied without much effort.

3.Ensure cuffs of the inner gloves are tucked under the sleeve of the gown. Removing gowns Gown front and sleeves and the outside of gloves are contaminated!

• If your hands get contaminated during gown or glove removal, immediately wash your hands or use an alcohol-based hand sanitiser

• Grasp the gown in the front and pull away from your body so that the ties break, touching outside of gown only with gloved hands

• While removing the gown, fold or roll the gown inside-out into a bundle

• As you are removing the gown, peel off your gloves at the same time, only touching the inside of the gloves and gown with your bare hands. Place the gown and gloves into a waste container

- Wear gowns and plastic aprons to protect clothing and skin from contamination.

Here are the methods to prevent contamination while applying, wearing and removing PPE.

1. Keep hands away from face and PPE being worn.

2. Change gloves when torn or heavily contaminated.

3. Limit surfaces touched in the patient environment.

4. Regularly perform hand hygiene.

5. Always clean hands after removing gloves.

What to do when disposing off used PPE

1. Follow strict organisational guidelines on disposing off contaminated PPE after use. This document will provide guidance on the use of PPE and organisations approved methods and instructions to remove, dispose off PPE safely.

2. Use a closed-lid waste bin According to the World Health Organization (WHO), PPE needs to be disposed of in a closed-lid waste bin rather than a regular bin precisely because it can be infectious or hazardous waste.

3. use dedicated waste bins for contaminated PPE Read organisations signage for disposal of clinical waste such as PPE. Most organisations will have clearly marked bins to know where to dispose of their PPE and prevent them from disposing of their mask or gloves in a regular bin, which could lead to others coming into contact (knowingly or unknowingly) with potentially infectious waste.

4. Removing PPE correctly Before the PPE is even put into the bin, you should know how to safely and hygienically remove PPE. The best prevention is awareness. Read signage carefully and many organisations now have signage in various languages around the workplace to ensure that you have clear, written instructions at your disposal. 5. Prevent overflowing of disposals If you see an overflowing bin immediately advise the supervisor or cleaning staff for it to be cleaned. Most organisations now have bins which are touch-free so using those are better as manually opening a bin could lead to the user touching a potentially contaminated surface and preventing others from coming into close contact with used PPE.

6. Disinfect units Finally, increased surface hygiene is part of every organisations response plan. This includes regularly and safely cleaning PPE disposal bins using disinfectants to kill any potential germs. Whoever is cleaning the PPE disposal bins should wear adequate PPE to avoid the possibility of being contaminated.

COVID-19 Precautions

COVID-19 precautions are an example of additional transmission-based precautions, meaning they are precautions that must be used in addition to standard precautions. There are variances in how different states and territories across Australia have implemented COVID-19 precautions, and you will need to seek specific guidelines and information on transmission-based precautions for your location.

You can check the guidelines for preventing and controlling the spread of infection:

- From your state/territory’s health authority

- From the Australian Government Department of Health

- For your community care sector

- For your organisation’s policies and procedures

Visit the following links for more information about the use of PPE in aged care settings (note that the same principles for PPE use in aged care apply to other settings):

- ‘Personal Protective Equipment for the Health Workforce During COVID-19’ from the Australian Government Department of Health

- ‘COVID-19 and What You Need to Know About Protective Equipment’ from Talking Aged Care

Watch the following video for more information about the use of PPE in aged care settings: ‘Coronavirus (COVID-19) wearing personal protective equipment in aged care video’ from the Australian Government Department of Health

What is Asepsis and its key principles in infection control

Asepsis is a set of practices that protect patients from healthcare-associated infections and protects healthcare workers from contact with blood, body fluid and body tissue.

Aseptic technique, when performed correctly it help minimise contamination and spread of infection. Its key principles includes:

1. Minimizing the amount of microorganisms and dust in the environment through general cleanliness of rooms, air and equipment.

2. Reduction of bacteria at the point of entry (skin or mucosa of patients) of the host through the use of antiseptics

3. Reduction of bacteria on the care provider especially the hands through hand washing, gowning and wearing sterile gloves.

4. Prevention of re-contamination of sterilized or disinfected instruments by avoiding contact between sterile and non-sterile items • Reducing predisposition of host to infection by: • minimizing tissue injury and ischaemia including excessive use of diathermy and sutures that are too tight • reducing presence of blood clots • shortening duration of retention of catheters / drains Following aseptic technique helps prevent the spread of pathogens that cause infection. sterile gloves sterile gowns, masks for the patient provide necessary barriers to protect the patient from the transfer of pathogens from a healthcare worker, from the environment, or from both.

Lets do a quick knowledge check by completing the quiz below, before you proceed further