In this section, you will learn to:

- Monitor and review the counselling process in collaboration with the client.

- Proactively identify and work on any threats and disruptions to the counselling process in collaboration with the client.

- Acknowledge, value, and work with individual uncertainty in the counselling relationship.

- Appropriately manage legal and ethical issues throughout the counselling relationship.

Supplementary materials relevant to this section:

- Reading E: Managing Resistance

- Reading F: Moral Principles to Guide Decision Making

Once the counselling process is underway, it is important to monitor it to continue to ensure effective counselling practice. This involves seeking client feedback and addressing any issues that arise during the counselling process. While appropriate planning and preparation can help facilitate a smooth counselling relationship and process, it is rare for everything to go 100% according to plan. Counsellors need to continually monitor, review, and adapt their work with clients to ensure that it remains effective.

Counsellors cannot simply assume that the help they are offering their clients is meeting their needs perfectly. Regular monitoring and reviews are important and should involve checking that the client is satisfied with the counselling process and strategies used and that the counselling process is helping the client meet their needs/goals.

There are two main types of monitoring processes:

- Informal monitoring: This involves any informal discussions the counsellor has with the client regarding the counselling relationship and process.

- Formal monitoring: This involves any planned, formal processes of seeking feedback and reviewing the counselling process. Formal monitoring typically involves a structured method of asking questions in the form of an interview, questionnaire, or feedback form or using standardised measures or inventories to measure client progress in specific domains.

Counsellors typically use a combination of these monitoring processes, but they must always ensure they comply with their organisation’s policies and procedures for evaluation. For example, some organisations may require counsellors to conduct a brief review at the end of each session; others may require an evaluation after a set timeframe (such as every three to six weeks). As you should recall, counsellors must discuss monitoring processes with the client in the initial counselling session and agree on the processes that will be used. This should then be documented in the counselling plan.

The following transcript illustrates how a counsellor might conduct an informal check with a client to see if the strategies being used are helping the client:

| Counsellor: | How are things going for you and your wife now? |

| Client: | Better. Every time I start to get angry and think about criticising her, I can stop myself before I say anything. |

| Counsellor: | So the work we are doing is helping? |

| Client: | I think so. I’m beginning to be able to let go and let things be. I don’t get so angry anymore. I have stopped expecting her to be how I want her to be all the time. |

| Counsellor: | Has your wife noticed? |

| Client: | Yes. She wants me to have counselling forever. She says I’m much nicer to be around now. |

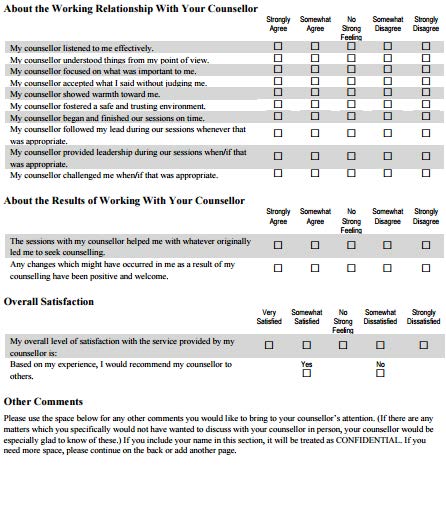

The following is an example of a Client-Counsellor Feedback form (pdf) from Counselling Resource (2003):

Generally, the feedback and monitoring process will focus on:

- A review of the progress that has been made towards the client’s goals

- Evaluation of and discussion about the effectiveness of specific techniques

- Evaluation of the counselling relationship (from the client’s perspective)

- Evaluation of the pace of the counselling progress

- Feedback from the client on what is working well for them and what is not

- Re-evaluation of the termination (final session) date if required.

Examples of common questions that counsellors ask their clients include:

- “Are you happy with the progress you are making in the sessions?”

- “Do you think you are closer to achieving the goals you have set for yourself?”

- “Are you comfortable with this style of counselling?”

- “Do you think we are going too fast/too slow with the counselling process?”

- “Are you comfortable with the pace of the sessions or would you like some changes?”

- “Are there any parts of our sessions that you are finding particularly useful?”

- “Is there any part of the counselling you are not enjoying?”

- “Are there any issues or concerns that you would like to address but that we haven’t talked about?”

Counsellors must reflect upon the information gathered from feedback, monitoring, and evaluation processes and adjust the counselling process as needed. This might involve changing the focus or pace of counselling, incorporating new goals into the counselling plan, or reviewing the date of the final counselling session.

high risk and sensitive phrases for progress notes

Although counsellor's should never try to hide critical information from therapy notes, there are many times when writing the details is unnecessary or even undesirable. In the following video, Dr. Maelisa McCaffrey provides counselors specific phrases to use for case notes when sensitive and high risk topics are addressed in a therapy session. As well as, how much detail you need to document and how to make these decisions ongoing.

watch

The monitoring and review process can sometimes reveal discrepancies between the counsellor's perception of the client's progress and the client's own perceptions. For example, clients may feel disappointed that they have not made as much progress as they would have liked. However, the counsellor may have identified changes that the client has not yet noticed themselves and might believe that counselling is progressing well. In such cases, it can be useful for the counsellor to share their perspective to help the client identify positive changes that have been made.

In cases where the counsellor and client agree that the client is not making the expected progress, it is important to explore this and identify why. Depending upon these reasons, it might be appropriate to modify the counselling approach/interventions, redevelop goals, or discuss referral options. If a counsellor is ever unsure of how to proceed with a client, it would be appropriate for them to consult their supervisor. Indeed, supervision is an important part of monitoring and review. As Geldard and Geldard (2009) state, all counsellors need to engage in supervision to help them effectively monitor, reflect, and review their progress with clients. The advice and feedback received in supervision can enable counsellors to gain objective insight into their performance and skills as well as learn additional skills that can be used to improve their practice with particular clients.

Ultimately, in cases where the client’s expectations are not being met in the sessions (e.g. if the client is not satisfied with their progress or not happy with the interventions being used), the counsellor should address the client's concerns and help the client to explore options (e.g., the use of interventions they would be more comfortable with or amendments that could be made to the counselling plan).

In some cases, the feedback and monitoring process can reveal that the client has unrealistic expectations about the counselling process that need to be addressed.

Anxiety and Progress Notes for Therapists

Dr. Maelisa McCaffrey reviews how anxiety in therapists can impact writing progress notes. She shares what leads to this common issue and provides one quick tip counsellors can use to improve their therapy case notes.

watch

Check your understanding of the content so far!

It is important to establish from the outset of counselling what the client’s expectations of counselling are and to ensure that their goals are realistically achievable. For example, clients often come to counselling hoping to receive advice and direction and may display resistance to working through their concerns from their own internal resources. It is important that clients are aware that counselling is a journey that requires them to engage in the process both cognitively and emotionally, albeit at a pace that they are comfortable with. Along the way, it may be necessary to address or revise client expectations of you, your time and resources, as well as the resources of your organisation.

The Working Relationship (Between Client And Therapist)

One of the most important concepts in Psychotherapy is trust, safety, security and understanding so the client feels able to peel back the layers. In this video topics such as silence in the therapy room, attunement and containment rhythm are discussed to see how you can work through the process of understanding, awareness and cure with the client.

watch

Some examples of client expectations that may need to be addressed include:

- A client expects you to decide for them or act on their behalf.

- A client expects to be "fixed" or "cured" in a designated number of sessions.

- A client demanding to see you more regularly even when you have a full client schedule and cannot accommodate this request and do not believe the client would benefit from additional sessions.

- A client demanding contact outside of their scheduled appointments.

- A client who has been referred for a particular number of sessions by their employer, GP, or case manager (who is arranging payment for services) and who wishes to continue counselling past the contracted sessions with no additional payment.

In some circumstances, it may be necessary to inform the client that their request cannot be fulfilled, using a gentle but firm manner, and clearly explain what is realistically possible. As much as you might want to try to accommodate all client requests, overstretching yourself to meet unrealistic expectations can lead to stress and eventually put you at risk of burnout. Bending the rules for a client and meeting their additional expectations even once can set a precedent for them to expect this from you in the future. It is important to ensure you always abide by your organisation’s policies and procedures. These protect the client, you, and your organisation.

Counsellor Video Case Study: Entering into a nonprofessional relationship with a client

This case involves a licensed marriage and family counsellor who entered into a nonprofessional relationship with a client, leading to both a malpractice lawsuit and a licensing board complaint.

Watch the video and then answer the question that follows.

watch

Even when the counsellor establishes a successful working alliance with the client, other factors may be present that can prohibit successful goal attainment and disrupt the counselling process. Many clients not only have to confront anxieties and fears as they address self-defeating behaviours, emotions, thoughts and attitudes, but they may also face additional barriers that can prevent them from achieving their goals. Some common barriers to the counselling process include:

The initial decision to meet with a counsellor is courageous. Many clients reach the counselling room physically. However, they may not be emotionally and mentally prepared for the process. One of the major barriers is the feeling of shame that clients carry, making it difficult for them to reveal and freely discuss the problems they are experiencing. They may even consider themselves as ‘faulty’ for needing help. Shame is often expressed by lowered eyes, minimal eye contact, stammering, voice fluctuations, squirming in their seat, and nervous laughter. A counsellor’s role is to help clients establish acceptance toward their problems and then help normalise their issues, assuring the client they are not ‘faulty’ or ‘different’ and that many people require assistance. Often, it may assist a client in gaining rapport and feel more comfortable if they are encouraged to talk about issues other than the primary issue first. As they gain further confidence and trust in the relationship, the client will often feel more at ease to broach the issues causing their ‘shame’.

Clients who have experienced painful events, such as the death of a loved one, divorce, abuse, and rejection, may not easily be able to reveal their innermost feelings to a stranger. When clients have been deeply hurt in past relationships, trusting a counsellor with intimate details of their experiences can be difficult. Counsellors need to tread carefully when clients show resistance to divulge information or emotions and pace the counselling conversations with due empathy and care, holding the client’s information with great sensitivity. This helps to build trust and rapport in the relationship, enabling the client to feel safe and gradually more comfortable sharing their concerns.

Uncertainty in the counselling process can arise for the client at any time. It is important for the counsellor to recognise any uncertainty as soon as possible and address it. A client may be uncertain about the counselling process, the counsellor, their need for counselling, their rate of progress, or about what they should expect from counselling. Clients experiencing uncertainty may also actively hold back from exploring certain issues, and counsellors must appreciate the client’s need to protect themselves in such instances. Examples of what a counsellor might say or ask a client experiencing uncertainty include,

“I can see that what I asked doesn’t feel right to you; can we stop for a moment and discuss it?” or “I think you’re absolutely right to stop here for now. It’s good to see you being careful of yourself and not just plunging into topics because I suggest them. I want you to keep telling me if anything like this seems uncomfortable or too hurtful.”

Additionally, rapport may seem difficult to establish or may begin to diminish at a certain point in the counselling process. The counsellor may feel that the client’s progress has stopped. A client who is uncertain about his or her progress may become frustrated with the counselling process and seem hostile. Uncertainty usually becomes apparent in a client’s non-verbal communication, even though the client may not verbally express it.

The following extract explores what is known as ‘client resistance’. Some counselling theorists see client resistance as an attempt on the client’s part to avoid making changes, while others view it as a natural response to feeling threatened when a client feels uncomfortable or uncertain about their own or the counsellor’s abilities. In both cases, resistance is something to be respected, understood, and explored.

Seemingly sensible exploration sometimes hits a stone wall of silence, protest, denial of relevance, or refusal to respond. Refusals to follow the clinician’s leads or suggestions are referred to as resistance. Resistance to clinician questions should not be seen as a negative trait of the client. Clinicians should appreciate the clients’ needs to protect themselves from questions that might create more distress or a threat to their sense of stability. Resistance may signal a need for caution.…

When the client balks at further elaboration, the clinician can simply reflect the resistance. Another response is to use the skill of examining the moment to explore why the person doesn’t want to continue on this topic.

(Murphy & Dillon, 2015, p. 206)

Counsellors must be patient with clients’ needs to safeguard themselves from going deeper into areas they are not yet ready for. Rather than feeling frustrated and taking the client’s resistance personally, the counsellor should reflect on it by asking a question like, “It looks like you are uncomfortable talking about this subject”. Another way a counsellor may ‘examine the moment’ could be to ask, “How does talking about this make you feel?”

Read

Reading E - Managing Resistance

Some clients find it particularly difficult to participate in counselling. It is important that counsellors learn to identify and work positively with resistance, without putting up further obstacles for clients to enter the process. Reading E provides some suggestions on understanding and managing client resistance from the early phase of counsellin

Why Am I Here?

This video provides an example of a counsellor dealing with a resistant client.

Watch the video and then answer the question that follows.

WATCH

Reluctance and ambivalence: In your role as a counsellor, you may be required to work with clients who have come to counselling due to pressure from other people, such as their parents, their partner, their friends, or their employer. You may also need to work with involuntary clients who have been mandated to attend counselling, imposed upon them by a legal authority. These clients may attend counselling in an unmotivated, reluctant state. Involuntary clients are often known to reject the ‘notion’ that they have a problem or may state that circumstances or other people are at fault or are the cause of their issues. Even when they admit to having a problem, they may be uncertain or sceptical that counselling will be of any benefit.

On the other hand, ambivalent clients may begin the counselling process aware of compelling reasons to make the desired changes but may be unwilling to put in the work required to make those changes. It can sometimes be difficult for counsellors to encourage reluctant or ambivalent clients to take the steps required to arrive at their goals. It is, therefore, necessary to develop the required skills to uncover and tap into a client's motivation, assist them in acknowledging the need for change, and work with them to help overcome their reluctance or ambivalence.

Building Alliance With Defensive, Angry Clients

A strong therapeutic alliance is key to a successful outcome, regardless of your clinical approach. This role play focuses on the key factors to developing this crucial aspect of therapy with even the most difficult clients.

Watch the video and then answer the question that follows.

watch

Nelson-Jones (2013) offers the following suggestions for counsellors to address and manage client resistance and reluctance:

- Use active listening skills, being highly attentive to the client

- Join with clients and be on their side – clients will often respond if they feel that the counsellor is there to help them and is not the person who pressured them to attend counselling

- Give your client permission to discuss their reluctance and fears about the counselling process

- Invite cooperation and establish a good collaborative working relationship with your client

- Enlist client self-interest – assist clients in identifying reasons, benefits or gains for them to participate in counselling

- Reward and encourage silent or quiet clients for talking.

Counsellors must work to address such barriers when they present themselves in the counselling process. This often involves working with the client at a pace and in a manner that they are comfortable with. For example, trying to facilitate change too quickly with reluctant clients can lead to them entirely disengaging from the process. Remember, the client's experience of the counselling relationship is one of the central components of effective counselling practice, so it is important for counsellors to work with clients to identify and appropriately manage any threats and disruptions to the counselling relationship to ensure effective counselling practice.

Engaging Reluctant Clients in Therapy

The counsellor in this video discusses how to engage a reluctant client.

watch

Physical obstacles that effect the counselling relationship

Counsellors and counselling organisations need to be aware of these physical obstacles and work towards minimising their impact, ensuring accessibility, and providing suitable accommodations to ensure that counselling services are available to individuals regardless of physical limitations.

Ethical practice is also central to effective counselling practice. Throughout the counselling process, counsellors should monitor their work in order to ensure that they are acting in an ethically appropriate manner. This includes maintaining the limits and boundaries of the counselling relationship.

The following extract from the Australian Counselling Association Code of Ethics and Practice (2013) outlines essential practices to be followed by counsellors to maintain ethical boundaries with clients.

3.9 Boundaries

- With Clients

- Counsellors are responsible for setting and monitoring boundaries throughout the counselling sessions and will make explicit to clients that counselling is a formal and contracted relationship and nothing else.

- The counselling relationship must not be concurrent with a supervisory, training or other form of relationship (sexual or non-sexual).

- With Former Clients

- Counsellors remain accountable for relationships with former clients and must exercise caution over entering into friendships, business relationships, training, supervising and other relationships. Any changes in relationships must be discussed in counselling supervision. The decision about any change(s) in relationships with former clients should take into account whether the issues and power dynamics presented during the counselling relationship have been resolved. Section 3.9 (b) ii below is also of relevance here.

- Counsellors are prohibited from sexual activity with all current and former clients for a minimum of two years cessation of counselling.

(ACA, 2013, p.11)

A situation in which a counsellor is acting in their professional role with a client in addition to another role with the same person is known as a multiple or dual relationship. According to Corey, Corey, Corey and Callanan (2015), this can include more than one professional role (such as instructor or therapist) or the blending of a professional and non-professional role (such as counsellor and friend). Multiple or dual relationships can also include:

- Providing counselling to a relative or friend’s relative.

- Socialising with clients.

- Becoming emotionally or sexually involved with a client or former client.

- Combining roles of supervisor and counsellor/therapist.

- Having a business relationship with a client.

- Borrowing or loaning money to/from a client.

Maintaining appropriate boundaries in a counselling relationship is important and helps remove the potential for inappropriate action. As Geldard and Geldard (2009) state, it is “unhelpful and damaging to the client when the client-counsellor relationship is allowed to extend beyond the limits of the counselling situation…the counsellor’s ability to attend to the client’s needs is seriously diminished” (p. 354). Counsellors must be aware of the danger signals that indicate a relationship with a client is becoming too close or a strong dependency is developing. Once identified, the counsellor should either discuss this with the client and take appropriate steps to re-establish the boundaries of the relationship or seek advice from their supervisor when unsure about the best way to address the issue.

While boundary issues can be fairly easy to identify and address, there is a range of other ethical practice issues that can be more difficult to manage. Throughout the counselling process, counsellors may come across a range of ethical dilemmas that they will need to manage appropriately. An ethical dilemma is a complex situation that involves conflict between two ethical principles where a choice needs to be made. For example, imagine a counsellor working in a rural community who has a client come to counselling with a problem they have no knowledge or experience with. To take on this client would be to ignore the principle of competence; however, denying the client would potentially mean they would not receive counselling help at all. This would conflict with the counsellor's commitment to the well-being of clients. This constitutes an ethical dilemma for the counsellor.

Check your understanding of the content so far!

So, how should counsellors decide how to proceed in the face of ethical dilemmas? One way of appropriately managing ethical dilemmas is to consider their ethical codes of conduct and use a step-by-step ethical decision-making model. One commonly used ethical decision-making model was proposed by Corey, Corey, Corey and Callanan (2015). It states that counsellors should complete the following steps:

- Identify the problem or dilemma.

- Does the situation truly involve an ethical situation or is it more likely a legal, clinical, professional, or moral problem?

- What is the crux of the dilemma? Who is involved? What are the stakes? What insight does the client have regarding the dilemma? How is the client affected by the various aspects of the problem? What are your insights about the problem?

- Identify the potential issues involved.

- List and describe the critical issues and discard the irrelevant ones.

- Evaluate the rights, responsibilities, and welfare of all affected by the situation.

- Identify and evaluate the relevant ethical principles.

- Review the relevant ethics codes.

- Ask yourself whether the standards or principles of your professional organization offer a possible solution to the problem – seek guidance from your professional organisation.

- Consider whether your own values and ethics are consistent with, or in conflict with, the relevant codes – do you have rationale to support your position?

- Know the applicable laws and regulations.

- Keep up to date on relevant state and federal laws that might apply to ethical dilemmas.

- Understand the current rules and regulations of the agency or organization where you work.

- Obtain consultation.

- Consult your supervisor.

- If there is a legal question, seek legal counsel.

- If the ethical dilemma involves working with a client from a different culture, consult a person who has expertise in this culture.

- If a clinical issue is involved, seek consultation from a professional with appropriate clinical expertise.

- Are there factors you are not considering? Have you thoroughly examined all of the ethical, clinical, and legal issues involved in the case?

- Consider possible and probable courses of action.

- Brainstorm to identify multiple options for dealing with the situation.

- Consider the ethical and legal implications of the possible solutions you have identified.

- What do you think is likely to happen if you implement each option?

- Enumerate the consequences of various decisions.

- Consider the implications of each course of action for the client, for others who are related to the client, and for you as a counselor.

- Examine the possible outcomes of various actions, considering the potential risks and benefits of each action.

- Choose what appears to be the best course of action.

- Carefully consider the information you have received from various sources.

- How does your action fit with the code of ethics of your profession?

- To what degree does the action taken consider the cultural values and experiences of the client?

(Adapted from Corey, Corey, Corey and Callanan, 2015)

Read

Reading F - Moral Principles to Guide Decision Making

Reading F explores fundamental principles guiding helping professionals’ ethical decision-making, including autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence, justice, fidelity, and veracity. You will also read more about the ethical decision-making model.

In the process of making ethical decisions, it is also important to involve the client when possible. Because you are making decisions about what is best for their well-being, it is best practice to discuss the nature of the ethical dilemma with them. Consulting fully and appropriately with the client is an essential step in ethical decision-making. When we collaborate with clients and solicit their perspectives, they are not only empowered, but it also increases the chance of arriving at the best resolution for any ethical questions that arise.

An integral part of recognising and working through an ethical concern is to discuss your beliefs and values, motivations, feelings, and actions with a supervisor or a colleague. When faced with an ethical dilemma, it is also important to thoroughly document your decision-making process so that it is clear to yourself and anyone else involved why you took a specific course of action or crossed what is usually an ethical boundary in the counselling relationship.

Reflect

Take a moment to reflect upon the ethical dilemma introduced previously (i.e., working as a counsellor in a rural town and meeting a potential client you do not have the competence to see). What would you do? Read through the ethical decision-making steps and see if you can come to a decision.

Professional Codes and Ethics and Practice will provide invaluable guidance in dealing with ethical issues and dilemmas. Your supervisor will also be an excellent source of guidance and advice. We recommend you access and become familiar with the Australian Counselling Association’s Code of Ethics and Practice and refer to it regularly throughout your Diploma. It can be downloaded from the ACA’s website.

In addition to becoming familiar with the Code of Ethics and Practice, all counsellors need to know the full range of legal and ethical considerations involved in the counselling relationship. You have been introduced to these concepts earlier in your Diploma, and you will also learn more about them in CHCLEG001 Work legally and ethically. However, the following table has also been included to overview these considerations briefly.

| Human rights | Every individual has basic human rights that must be respected. In the counselling context, counsellors should respect a client’s human rights, such as the right to individuality, their own values and beliefs, and freedom of choice. |

|---|---|

| Discrimination | Discrimination occurs when an individual is treated differently, in a way that is not helpful, based on a characteristic about them (e.g., gender, disability, race, age or sexual preferences). |

| Duty of care | This term refers to a counsellor’s responsibility to protect the well-being of both clients and others who may be severely impacted by a client’s actions. |

| Practitioner/client boundaries | Counsellors are responsible for maintaining appropriate boundaries with a client (i.e., limiting the client-counsellor relationship to a professional contract/agreement only). |

| Privacy | Clients have a right to privacy. Counsellors should take appropriate actions to protect client privacy (e.g., ensuring sessions are not overheard, recorded or observed without the client's consent) and protect the client’s personal information and session notes. |

| Confidentiality | Counsellors must keep what clients tell them during sessions secret and private (except in cases where duty of care and other limitations apply). |

| Disclosure | This is a term used to refer to the information that a client reveals during counselling sessions. |

| Rights and responsibilities of workers, employers and clients | Clients and employers have their own responsibilities and rights. As a counsellor, you must be aware of the organisational responsibilities that may apply in your workplace. |

| Work role boundaries | The counsellor’s role has specific boundaries. Counsellors cannot be ‘everything to everyone’. Counsellors should acknowledge the limitations of the counsellor role and not act outside their role boundaries (this includes making appropriate referrals to a more specialised service if appropriate). |

| Work Health and Safety (WHS) | Counsellors are responsible for ensuring that the work environment is safe for themselves, other workers, and clients. |

Ensuring that counselling practice conforms to all legal and ethical requirements should form part of the monitoring process. After all, if legal and ethical boundaries are being breached, the counselling work is unlikely to be effective.

Check your understanding of the content so far!

Counsellors have a responsibility to monitor the ongoing counselling relationship and process. In this module section, you learned about several key considerations involved in monitoring and ensuring the ongoing effectiveness of counselling. Part of the monitoring process also involves assessing if it is time to bring the counselling relationship to an end. You will learn more about the ending process in the next section of this module.

- Australian Counselling Association (2013). Code of ethics and practice of the Association of Counsellors in Australia. Retrieved from https://www.theaca.net.au/documents/ACA%20Code%20of%20Ethics%20and%20Practice%20Ver%2010.pdf

- Corey, G. Corey, M. S., Corey, C., & Callanan, P. (2015). Issues and ethics in the helping professions (9th ed.). Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.

- Counselling Resource (2003). Client-counsellor feedback form. Retrieved from http://counsellingresource.com/lib/wp-content/managed-media/feedbackform.pdf

- Geldard, D., & Geldard, K. (2012). Basic personal counselling (7th ed.). Frenchs Forest, NSW: Pearson Australia.

- Murphy, B.C. & Dillon, C. (2015) Interviewing in action. (5th ed.). Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.

- Nelson-Jones, R. (2013). Introduction to counselling skills (4th ed.). London, UK: Sage Publications.