In this section, you will learn to:

- Determine client suitability for acceptance and commitment therapy.

- Work with clients using an ACT approach.

- Document and monitor progress in ACT.

- Apply ACT to particular client issues.

Supplementary materials relevant to this section:

- Reading F: Case Conceptualisation Worksheet

- Reading G: Where Do I Start?

Now that you understand ACT's key concepts and techniques, let’s look at some key considerations in applying ACT within the counselling practice.

Before applying any specific counselling approach with a client, a counsellor must evaluate whether the approach suits the client and the client’s issue. ACT is a widely used approach that is effective for a wide range of clients and client issues, including common interpersonal issues, stress-related issues, anxiety-related problems, substance use problems, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorders, social phobia, chronic pain, stress, and health and disease management (Masuda & Rizvi, 2020; Harris, 2019). ACT has also been found to have a lower drop-out rate than other therapies and is rated highly by clients (Stoddard & Afari, 2014). Additionally, ACT has great flexibility and can be successfully delivered in brief formats, modified depending on the client’s needs, and used with couples and groups (Flaxman, Blacklege & Bond, 2011). Indeed, Harris (2019) advocates for ACT to be used with almost anyone, as the following extract illustrates:

Therapists often ask me, “Who is ACT suitable for?” My reply is, “Can you think of anyone it’s not suitable for?” Who wouldn’t benefit from being more psychologically present; more in touch with their values; more able to make room for the inevitable pain of life; more able to defuse from unhelpful thoughts, beliefs, and memories; more able to take effective action in the face of emotional discomfort; more able to engage fully in what they’re doing; and more able to appreciate each moment of their life, no matter how they’re feeling? Psychological flexibility brings all these benefits, and more. ACT therefore seems relevant to just about everyone.

(Harris, 2019, p. 36)

However, ACT may not be useful for every client. Due to the nature of the ACT therapeutic process, it might not be suitable for clients with deficits in their language abilities and cognitive functioning, such as people with severe autism, acquired brain injuries, or other disabilities (Harris, 2019). In addition, some clients may not want to work with an ACT approach – remember, as a counsellor, it is always important to explain your counselling approach to obtain your client’s informed consent. For example, clients who wish to engage in a long-term discussion of their past and problems might wish to engage in another counselling style. Additionally, concerning the six core therapeutic processes, Westrup (2014) warns counsellors about assisting clients in fostering behavioural abilities rather than teaching them concepts. If clients believe they will become psychologically flexible once they are able to do the six conditions, they will feel as though they have reached a destination rather than seeing the concepts as processes that should be constantly developed throughout the lifespan (Westrup, 2014).

3 Helpful Metaphors To Help Depressed Clients

In this video, Mike Tyrell share three powerful, hopeful metaphors you can use to help your depressed clients gain a fresh perspective on their experience.

Watch

In Section 1, you learned about the six core therapeutic processes and how counsellors can use them to increase a client’s psychological flexibility. However, a common question that is asked by those new to ACT is which process should a counsellor start with.

Whilst it may vary in different contexts, the first session will generally involve the counsellor building rapport with clients, obtaining their informed consent, taking a history, and working with clients to establish behavioural goals (Harris, 2019). As you have learned, a compassionate and respectful relationship with clients is vital for effectively implementing the ACT approach. Regarding history taking, ACT is interested in gathering history only where it’s directly relevant to the current issues to develop self-acceptance and self-compassion. Other information that an ACT practitioner will be interested in includes the client’s presenting complaints, values, current life context, psychological rigidity and flexibility, motivational factors, and resources they have (Harris, 2019). With the information gathered from clients, the counsellor can begin developing a case conceptualisation from an ACT perspective.

Read

Reading F - Case Conceptualisation Worksheet

Reading F contains a case conceptualisation worksheet freely available on the ACT Mindfully website. The worksheet outlines the information that an ACT practitioner may assess and record in the process of considering which core ACT processes, exercises, metaphors and techniques might be useful.

Case conceptualisation helps a counsellor to better understand a client’s level of psychological inflexibility and which of the core therapeutic processes might be most important as a starting point. Of course, because all the therapeutic processes are interconnected, ultimately, the counsellor will work with the client on all of them.

Another important part of the initial session is to help clients develop behavioural goals. A counsellor may ask, “What will you do differently?”, “What will you start doing/stop doing?” or “What will you do more of or less of?” (Harris, 2019, p. 66). It is common for clients to come up with emotional instead of behavioural goals. For example, clients may want to recover from depression, feel better, or reduce anxiety, which are emotional goals rather than what they will do. In this case, ACT counsellors can help clients to reframe their goals into behavioural goals – learning a new skill. See the following example:

| Client: | I don’t want to do anything differently. I just want to stop feeling like this. I just want to get rid of these thoughts/feelings/emotions/memories. |

| Therapist: | So it seems like a big part of our work here will need to be about learning new skills to handle these difficult thoughts/feelings/emotions/memories more effectively. |

(Adapted from Harris, 2019, p. 67)

Harris (2019) also emphasises that it is important to set goals that are “living person’s” not “dead person’s goals” (p. 69). For example, “I want to stop using drugs” is a dead person’s goal because a dead person can do that more effectively than a living person. To help clients transform goals into a living person’s goals, you may ask questions like: “So if that happens, what would you do differently? What would you start or do more of? How would you behave differently with friends or family? If you weren’t using drugs, what would you be doing instead?” (p. 69).

Some counsellors can get a little overwhelmed by trying to keep each of the six core therapeutic processes in mind and deciding which to focus on at any given time. A more simplistic pathway that Harris (2019, pp. 83-84) proposes counsellors can take when engaging with new clients is to structure their approach around two key questions:

- What valued direction does the client want to move in?

- What is getting in the way?

The first path generally flows onto a values clarification exercise, followed by goal setting and committed action. This is also a useful starting point for clients unsure what they want from their lives. It is important to understand the difference between values and goals. Values are the direction clients want to move in, while goals are things they want to achieve or complete. For example, marriage is a goal and being loving is a value. Harris (2019) compares values to a compass that tells clients which direction to move in and keeps them on track, while goals are the markers along the way (e.g., the things that are achieved along the way).

The second path usually leads to using various ACT techniques to target the issues that are getting in the client’s way and helping clients to build skills to manage them. For instance:

- Target inflexible attention with contacting the present moment.

- Target fusion with defusion.

- Target experiential avoidance with acceptance.

- Target self-criticism, self-hatred, and self-neglect with self-compassion.

(Harris, 2019, p.84)

Once again, there is no specific way to implement ACT, and all six core processes will eventually be touched on throughout your work with the client. Ultimately, the counselling process, and the techniques, skills, and language used, support clients in developing their psychological flexibility – be present, open up, and do what matters.

Counselling Theory vs. Techniques

This video explains the difference between psychology, counselling theories and techniques.

Watch

Reflect

Take a few minutes to reflect upon each of the techniques you learned in this module's first section. Consider when you might choose to use each particular technique with a client.

Read

Reading G - Where Do I Start?

This reading outlines some considerations for structuring your ACT sessions with a client. Remember that these are no fixed sequences, and practitioners can work with any core processes at any point in a session. This reading is meant as a guide and one to be adapted for each client.

As with other approaches to counselling, ACT counsellors must keep records and document their work with clients. ACT counsellors should keep session notes about what was discussed, what was discovered about the client’s levels of psychological inflexibility, the client’s valued direction, and which therapeutic processes and techniques were used in any given session. Additionally, ACT counsellors should monitor their work with clients and seek to assess the client’s progress to determine if the current strategies are working or if changes need to be made.

In previous modules of your Diploma, you have learned how progress can be monitored, such as by asking clients about their perceptions of their progress and using client feedback forms. Similarly, ACT practitioners may review and monitor the counselling experience with clients in these ways, focusing on their psychological flexibility (instead of symptom reduction) and supporting the maintenance of valued-guided actions and skills. Other steps that an ACT practitioner may take to facilitate the helping process coming to an agreed end include:

- The therapist celebrates client’s successes, describing specific instances where the client demonstrated in-session skills and reported out-of-session use of skills.

- The therapist might share personally what was notable about this client’s journey in doing the work, moments where the therapist felt excited about changes the client was bravely making or a moment where something the client said in-session touched the therapist personally in an emotional way.

- The therapist might review objectives and agendas from previous sessions, outlining how the work of therapy has addressed these challenges uniquely. This is also an opportunity to consolidate learning by reorienting clients to processes, ways of thinking about problems and hopes, the functional perspective of behavior, and reinforcing a repertoire of using the processes out-of-session.

- Therapists may assess for issues of grief that may come up as termination approaches asking, “What has it meant to say goodbye for you in the past?” Depending on the client’s reactions to terminating therapy, it may be helpful to use relevant common core processes to address termination.

- In maintenance and in termination, therapists would be apt to ask, “What upcoming problems or future hurdles do you see yourself dealing with and how might you use what we’ve done here to make those situations more workable?” to prompt clients to anticipate future barriers and identify learned strategies for managing difficult or complex situations.

(Gordon, Borushok & Polk, 2017, p. 53)

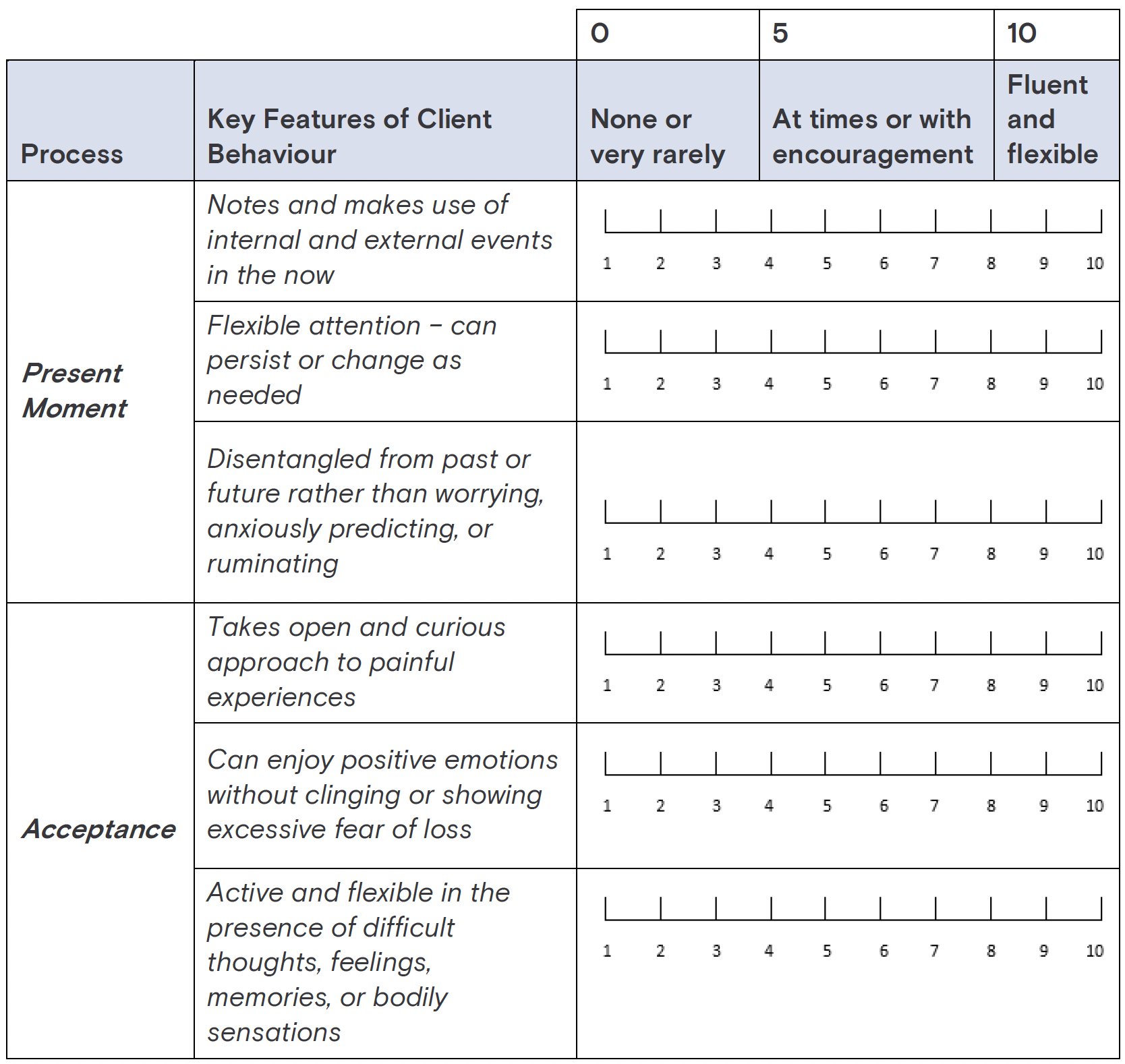

Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson (2012) have developed an additional way of monitoring the progress of a client’s psychological flexibility. They suggest using a Flexibility Rating Sheet that the counsellor can complete during or after a session with the client. This measure gives estimated scores to each of the processes of psychological flexibility and allows the counsellor to see if progress has been made in these areas. Hayes, Strosahl and Wilson (2012) recommend creating an average of the scores on the six processes to get an overall measure of psychological flexibility.

The following extract from a rating sheet is included here – a full version of the rating sheet would contain all six processes.

(Adapted from Hayes, Strosahl & Wilson, 2012)

It is also important for the counsellor to evaluate their role during the ACT process. This can be done through a self-evaluation, requesting feedback from the client, attending peer review with other counsellors to discuss their cases, and attending professional supervision.

Incorporating Progress Monitoring and Outcome Assessment in Counselling and Psychotherapy: A Primer

This video describes the major ideas and procedures of progress monitoring and outcome assessment.

watch

Reading through the following case study will help you better understand the processes and techniques of ACT.

Case Study

Social Anxiety

Paul is a 27-year-old man. He has been experiencing social anxiety since his teenage years, but currently, most anxiety centres around his job because he avoids social situations in his personal life. Paul works hard to suppress his anxiety at work, but in his last role, he was sometimes required to give presentations in front of large groups. He found this experience highly stressful; before one presentation, he even had a panic attack. As a result, Paul resigned from that position and took a much lower-paying back-office job where he doesn't have to interact with other people. Paul finds this job boring and wishes he didn’t have to give up his old role, which he found very interesting and rewarding (except when he had to give presentations).

Paul has decided to seek out counselling at the insistence of his mother. While Paul is open to the idea of seeking help, he does not see how he will ever be able to get rid of his anxious feelings.

After the standard contracting process, the counsellor begins by using the ACT in a nutshell metaphor to help introduce Paul to the concepts and processes of ACT. Paul is intrigued by these concepts. He likes the idea of changing his “relationship” to his anxiety, but he still doesn’t think that this will be able to “fix” him.

The counsellor talks Paul through the ‘Join the DOTS’ exercise, and Paul slowly starts realising that trying to control his anxiety is not working for him. The counsellor then gets Paul to act out the ‘Tug-of-War with a Monster’ exercise with him. The counsellor then ends the session with a simple mindfulness breathing exercise and asks Paul to practice the exercise over the next week.

In the next session, the counsellor reviews the worksheet with Paul and identifies that Paul is still struggling with the processes of defusion and acceptance. The counsellor decides to take Paul through the ‘The Struggle Switch’ exercise, and they spend the rest of the session debriefing on this exercise and working with ‘The Struggle Switch’. Paul opens up about how he has always struggled to control his anxiety, and the counsellor and Paul discuss how Paul can open up and accept his feelings without struggle. The counsellor concludes the session by asking Paul to continue to practice some mindfulness exercises and also complete the ‘Getting Hooked’ worksheet.

In the next session, the counsellor reviews the worksheet with Paul and conducts a thorough debriefing on Paul’s experiences and what he has learned. The counsellor then takes Paul through the observe, breathe, expand, allow, objectify, normalise, show self-compassion, and expand awareness mindfulness exercise. At the end of this exercise, the counsellor debriefs Paul, and they discuss what Paul has learned from the exercise. This leads to the counsellor using the ‘Continuous You’ exercise to help Paul begin to embrace self-as-context. At the end of the session, the counsellor asks Paul to practice some mindfulness techniques throughout the week.

In the next session, the counsellor begins by promoting Paul’s contact with the present-moment experience by having Paul complete the ‘Mindfully Eating a Raisin’ technique. During the debriefing of this exercise, the counsellor and Paul discuss all the things that Paul is missing out on in life by trying to control his anxiety and not being fully in contact with the present moment. Paul tells the counsellor that he enjoys the mindfulness techniques and is applying the concepts of letting his anxiety and other thought processes come and go without trying to control them. Paul tells the counsellor that he thinks that he is ready to look for a more fulfilling job. This leads the counsellor to complete the values clarification exercise ‘Imagine your Eightieth Birthday’. The counsellor concludes the session by asking Paul to complete the ‘The Life Compass’ worksheet.

At the beginning of the next session, the counsellor reviews Paul’s worksheet, and they debrief on what Paul has learned about himself from doing it. Together, the counsellor helps Paul develop goals that reflect his values and the direction he wants to travel in. This then leads to a discussion of potential barriers, and the counsellor takes Paul through the HARD acronyms and concludes the session by asking Paul to complete an action plan.

The remaining sessions focus on continuing to help Paul develop his psychological flexibility through ACT techniques and using some more specific behavioural techniques to help him develop skills that relate to his goals.Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Cognitive Defusion

Case Study examples

After watching the following videos, answer the questions that follow.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Cognitive Defusion

Watch

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Control & Acceptance

Watch

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): Psychological Flexibility

Watch

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): Mindfulness

Watch

In this module section, you have learned how ACT concepts and techniques can be applied in counselling practice. However, it is essential to remember that ACT is a specialist approach. Students interested in ACT are encouraged to seek further training and skill development to broaden their understanding and enhance their practice capabilities.

- Flaxman, P. E., Blackledge, J. T., & Bond, F. W. (2011). Acceptance and commitment therapy. Routledge.

- Gordon, T., Borushok, J., & Polk, K. (2017). Case conceptualization with ACT. In The ACT approach: A comprehensive guide for acceptance and commitment therapy, (pp. 35-53). PESI.

- Harris, R. (2019). ACT made simple: A quick start guide to ACT basics and beyond (2nd ed.). New Harbinger Publications.

- Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Masuda, A., & Rizvi, S. L. (2020). Chapter 6: Third-wave cognitive-behaviorally based therapies. In S. B. Messer & N. J. Kaslow (Eds.) Essential psychotherapies: Theory and practice (4th ed.) (pp. 183-217). The Guildford Press.

- Stoddard, J. A., & Afari, N. (2014). The big book of ACT metaphors: A practitioner’s guide to experiential exercises & metaphors in acceptance & commitment therapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

- Westrup, D. (2014). Advanced acceptance and commitment therapy: The experienced practitioner’s guide to optimizing delivery. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.