Barkway, P. (2013). Behavioural change programs. In Psychology for health professionals (2nd ed.) (pp. 160-166). Elsevier.

Behavioural change programs aim to change behaviour, not attitudes, beliefs, motivation, personality or other unobserved characteristics of individuals. Behaviour may be defined as anything that a person does or says; that is, behaviour is any action or response to an environmental event that is observable and measurable. Behaviours can be overt (readily observed and counted) or covert (not readily observed but can still be counted and changed, such as thoughts and feelings using the principles described in this chapter). Regardless of the orientation of specific programs, all behavioural change programs operate on the following four tenets:

- Behaviour can be explained by the principles of learning and conditioning.

- The same laws of learning apply to all behaviour, both normal and abnormal.

- Abnormal behaviour is the normal response to abnormal learning conditions.

- Behaviour can be ‘unlearned’ and changed.

These four tenets underpin the four major theoretical models that have been derived from learning theory, namely, classical conditioning, operant conditioning, observational (imitation) learning and cognitive behaviourism (Beck 1976, Ellis 1984, Meichenbaum 1974).

Historically, behaviour therapy referred to the techniques based on classical conditioning, devised by Wolpe (1958) and Eysenck (1960) to treat anxiety; behaviour modification was used to describe programs based on the principles of operant conditioning devised by Skinner (1953) to create new behaviours in children who had an intellectual disability and patients experiencing psychotic symptoms.

In current practice, the terms behaviour therapy, behavioural change programs and behaviour modification are used interchangeably to describe therapeutic programs based on the principles of behavioural/learning theory. The term ‘behavioural change program’ will be used in this chapter. The following outlines the principles a clinical psychologist would use when designing a behavioural program.

Functional Analysis of Behaviour

The principles of operant conditioning (learning by reinforcement) describe the relationship between behaviour and environmental events, both antecedents and consequences that influence behaviour. This relationship referred to as a contingency, consists of three components:

- Antecedents (i.e. stimulus events that precede or trigger the target behaviour)

- Behaviours (i.e. responses, usually the identified problem behaviour)

- Consequences (outcomes of the behaviour, i.e. what actually happened immediately after the problem behaviour occurred).

Specifying these contingencies forms the basis of a functional analysis of behaviour. The aim of a functional analysis is to identify factors that influence the occurrence and maintenance of a particular (problem or desired) response. This process should not be confused with other explanatory models that may seek to explain behaviour in terms of a medical diagnosis or a personality trait. Behavioural change programs are more concerned with the nature of our interactions with the environment than with our nature per se.

Conducting a functional analysis of behaveour is the first step in designing a behavioural change program. It consists of the three components outlined below.

1. Selecting the Target Behaviour

The target behaviour must be specified in such a way that it can be readily observed and measured. The behaviour of interest may be a behavioural excess (e.g. tantrums, exceeding the speed limit, driving while intoxicated) or a behavioural deficit (e.g. an eight-year-old who cannot tie his shoelaces, an adult who does not complete recommended physiotherapy exercises, a well elderly person who does not perform self-care activities). For the examples given, it will be clear that behavioural deficits are of two types: behaviours that exist in the behavioural repertoire of the individual but which the individual does not perform, and behaviours that are not in the behavioural repertoire of the individual and must be developed. It is important to distinguish among these different groups of target behaviour as each requires the application of different behavioural change strategies.

Behaviour must never be viewed in isolation. The behavioural change agent considers the setting in which the behaviour occurs, the nature of the task and then characteristics of the client. Behaviour may be appropriate performed in one setting and not another. For example, it would be appropriate for a three-year-old child who has just learned to take his clothes off to do so in the bathroom in his home, but not in a busy shopping centre. A behavioural change program in this instance would aim to teach the child the appropriate setting for performing this newly acquired behaviour. Behaviour may also be considered problematic due to its rate, duration or intensity rather than the behaviour itself. For example, taking a shower is a common behaviour that may become problematic if the person spends one hour doing so or showers multiple times through the day. In this case, the behavioural change program would aim to reduce the amount of time spent in the shower or the frequency of showers.

2. Identifying Current Contingencies

This process involves two steps. The first is identifying the stimulus event(s) (i.e. antecedents) that precede(s) an occurrence of the problem behaviour. This includes an assessment of the physical (where the behaviour occurs) and social (who is present) environment in which the behaviour occurs. Certain behaviours will frequently occur at a high rate in one setting and be absent or occur at a low rate in others. For example, parents may complain about their child throwing tantrums and being argumentative at home to the child’s teacher, who reports that the child is compliant and polite in the classroom. Alternatively, the teacher may notice that the child stays on task in some subjects and not in others or during the morning session but not during the afternoon. In the hospital setting, two nurses may discover that a particular patient rings the buzzer for nursing assistance twice as often for one nurse compared with another, or that a child with cerebral palsy is more likely to persist with his physiotherapy exercises when his mother is not in the treatment room. These observations provide important information about the stimulus events that may be controlling the target behaviour.

The second step requires identifying the consequences that follow the problem behaviour; that is, what happened after the behaviour was performed? To follow through with our examples above, did the parents respond to the child’s tantrum by giving the child what she wanted or did they ignore her tantruming behaviour? Did they engage in a verbal debate with the child when she talked back or did they calmly state their rule that talk backs would not be answered? In an aged care setting two nurses notice that an elderly resident rings the buzzer twice as often for one nurse compared with another – were there any differences in each of the two nurses’ responses to the buzzer ringing? A child does not cooperate with physiotherapy exercises when his mother is in the room – what was the mother doing in the treatment room during her child’s physiotherapy sessions? Answers to these questions are essential for effective behavioural management to occur.

3. Measuring and Recording Behaviour

There are five basic methods of measuring behaviour in healthcare settings:

- Narrative recording

- Counting or frequency data

- Timing or duration recording (temporal data)

- Checking or interval recording (categorycal data)

- Rating (Magnitude data).

Once you have specified the target behaviour and identified the setting in which this behaviour occurs, it is necessary to obtain a baseline of the frequency or length of its occurrence. The way you measure frequency or length depends on the nature of the target behaviour and what you wish to find out about the behaviour.

Narrative Recording

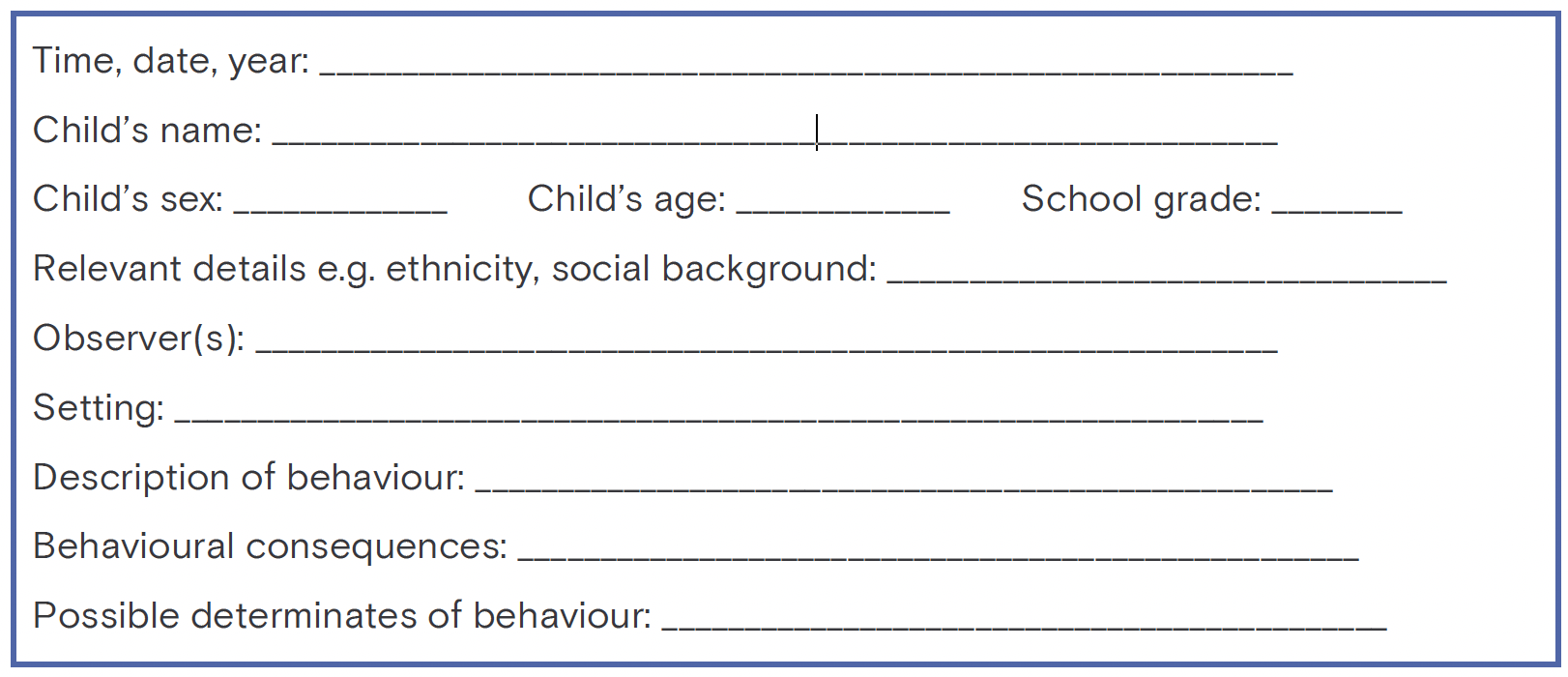

Narrative recording involves the observation and recording of behaviour in progress. It is often used in the early stages of the functional analysis of behaviour as a way of identifying possible antecedents and consequences of a given problem behaviour. Figure 7.1 provides an example of a narrative recording chart, for example, for a child with type 1 diabetes mellitus who refuses to take and record their blood sugar levels while at school.

Counting

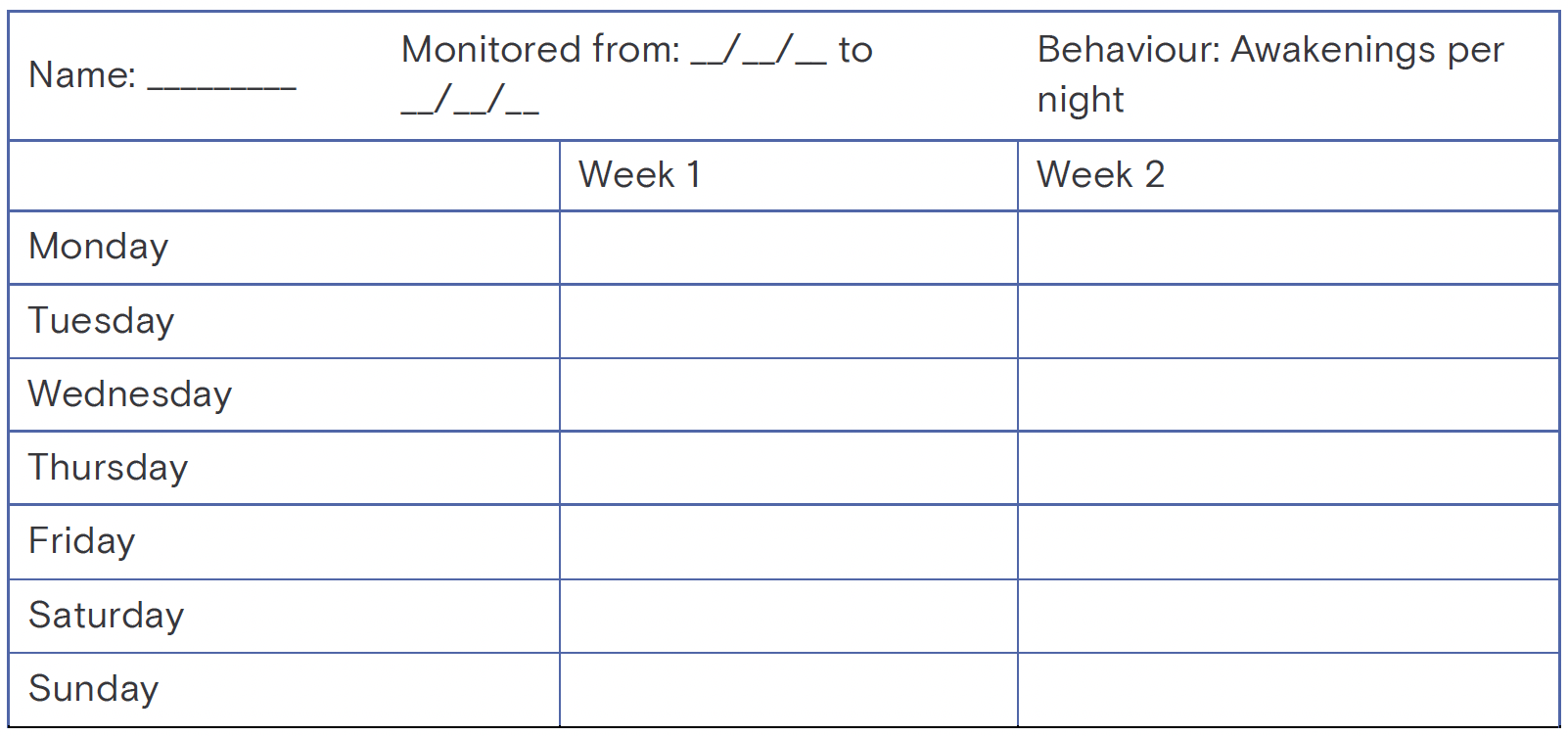

Counting is the method of choice if the target behaviour is discrete (i.e. an observer can identify the beginning and end of each instance of behaviour). Behaviours such as head banging, exercising and incontinence are examples of discrete, countable behaviours. Simple tally sheets or frequency counters can be used to record countable behaviours. One can also count the number of tasks complete or the percentage of items correct. These are examples of counts of the product or outcome of behaviour. They do not require continuous observation of the behaviour per se. Figure 7.2 provides an example of a recording chart for counting responses. In this case, the number of times the person awoke in the night is recorded.

Timing (duration)

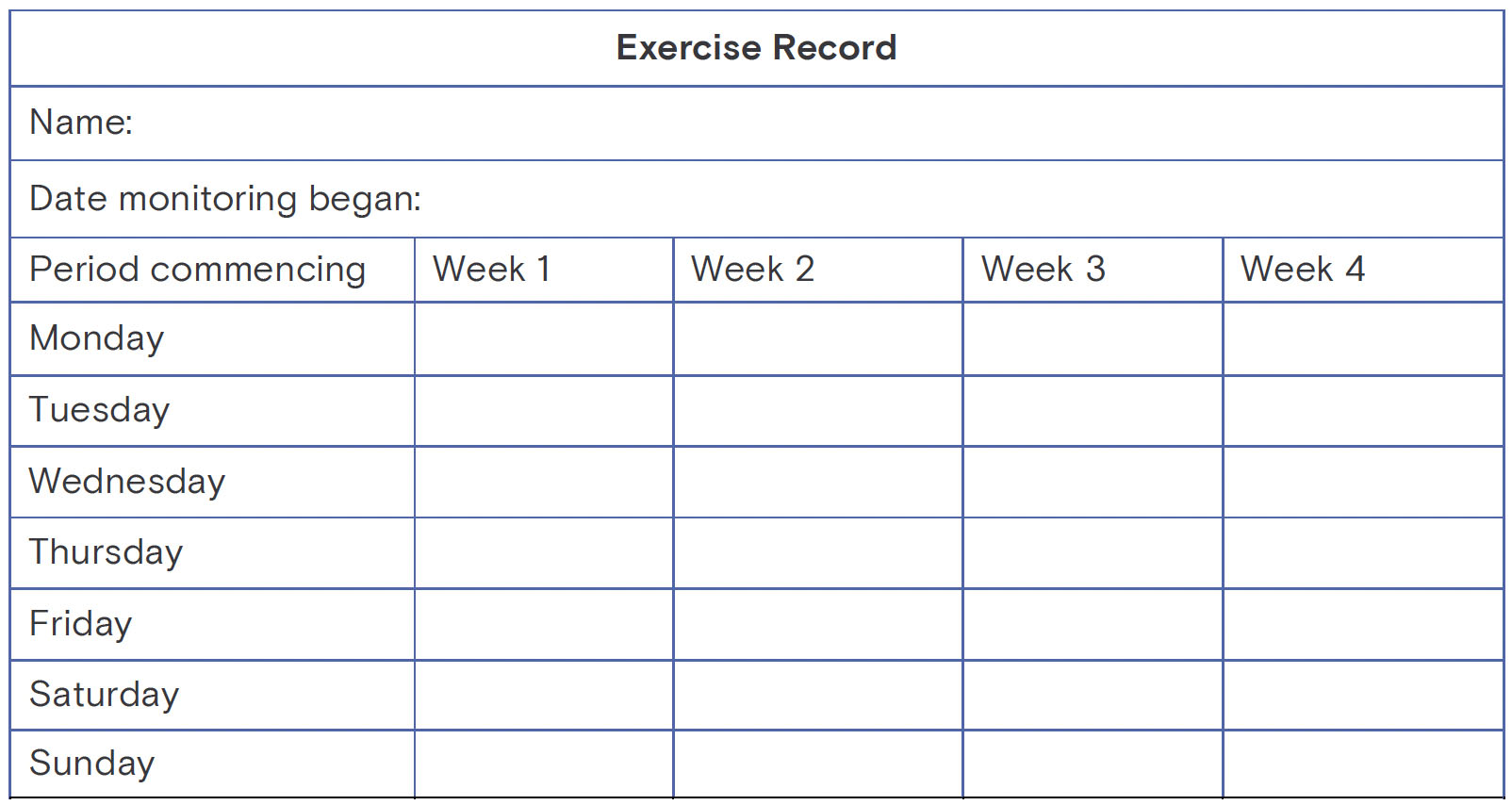

When a behaviour becomes a problem because of the length of time it takes to complete the task, or when you are interested in increasing the duration of a particular behaviour, you may choose to collect temporal data. Examples of behaviours for which temporal data are appropriate are length of time it takes for a doctor to perform a given task such as a surgical procedure, the length of time it takes for a hospitalised patient to shower in the morning or the amount of time a person spends in the gym practising physiotherapy exercises. Figure 7.3 provides an example of a chart for timing the duration of a target behaviour, in this case performing rehabilitation exercises in the gym over a four-week period.

Checking

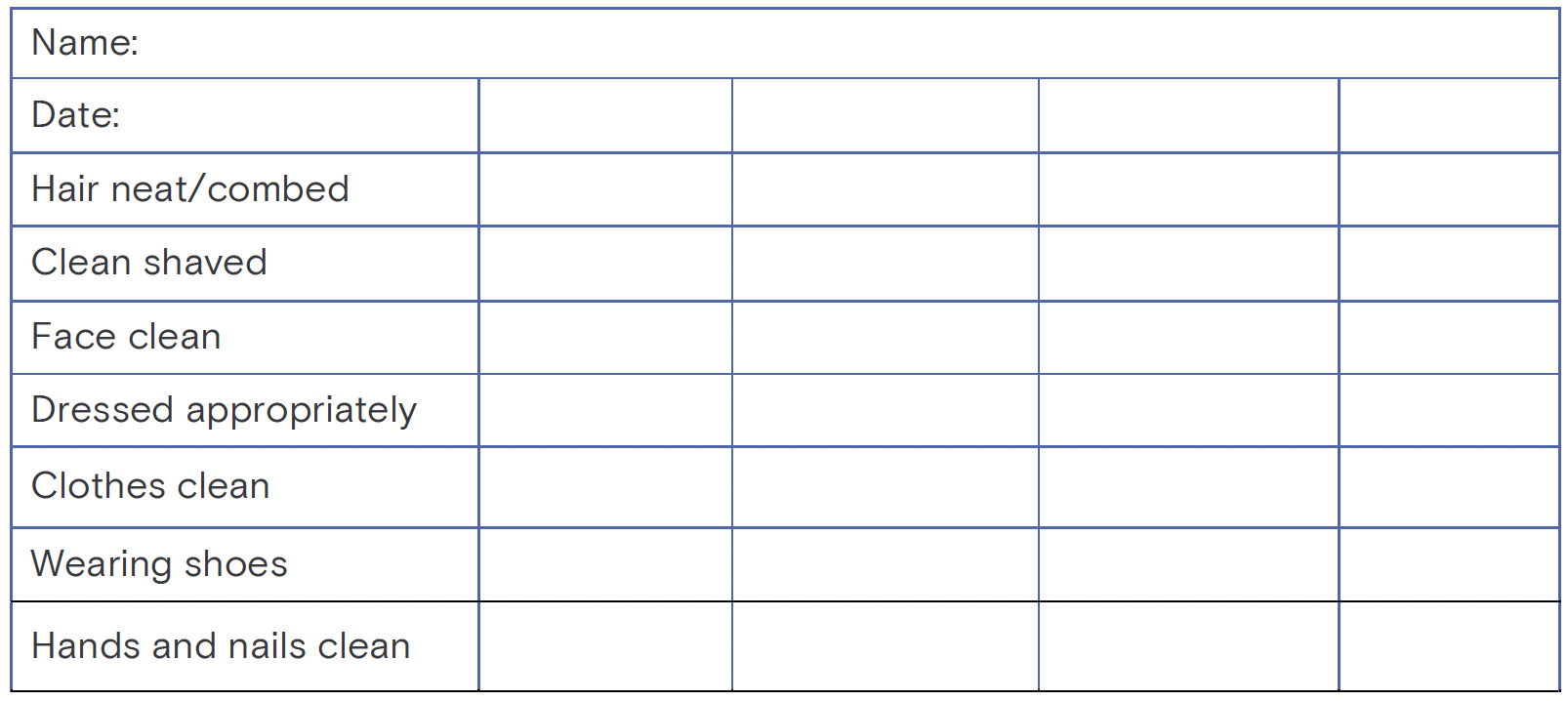

Checking or interval recording is used when you want to know whether an individual performs a specified task or not. In such cases your code requires a simple yes-no response. By checking on groups of related behaviours, you can quickly build up a picture of the individual’s current level of functioning. For example, you may wish to increase the self-care behaviours of a patient with advanced dementia. When he arrives at breakfast each morning, you can check whether he has combed his hair, shaved, dressed in day clothes (as opposed to pyjamas) and is wearing shoes. After you obtain a baseline following several days of checking, you will be ready to design a behavioural change program to address any outstanding deficits in self-care. Figure 7.4 is an example of a checklist, for example, for assessing how well a person with dementia manages their personal hygiene and grooming.

Rating

Rating is a method of assessing the quality of a response and, as such, requires a subjective judgment on the part of the observer. You may wish to assess the intelligibility of the speech of a person who is dysarthric. One quick measure of intelligibility is to ask the nursing staff and family to rate the person on a five-point scale ranging from 1 = very difficult to understand to 5 = very easy to understand.

In summary, a functional analysis of behaviour can identify the antecedents (what triggers the behaviour) and the consequences (outcomes of the behaviour).

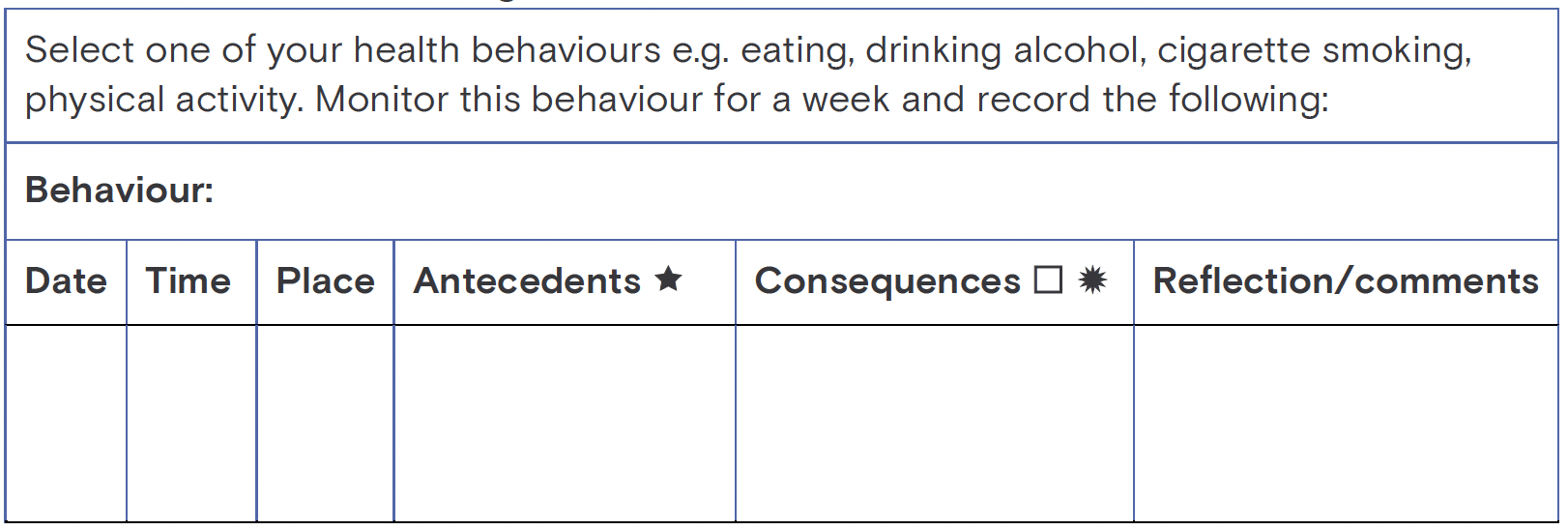

Consider one of your own health behaviours from a behavioural/learning perspective and monitor this for one week using the ‘Health behaviour monitoring exercise’ in Figure 7.5.

Figure 7.1 Narrative recording sheet for assessing a child’s problematic behaviour

Figure 7.2 Counting chart for (self) monitoring sleep disturbance over a two-week period

Figure 7.3 Chart for recording the amount of time spent in the gym over a four-week period

Assessment of Self-Care Behaviour

✓ - Satisfactory

X - Not present or unsatisfactory

N/A - Not applicable

Figure 7.4 Checklist for assessing self-care behaviour

Health Behaviour Monitoring Exercise

★ Antecedents: Where are you? Who else was present? What were your preceding thought or feelings? What events preceded/coincided with the behaviour?

Consequences: What was the outcome? What were your subsequent thought or feelings?

Figure 7.5 Health behaviour monitoring exercise