Reading A: Heimlich Manoeuvre

Reading B: Boyle’s Law

Reading C: Upper Respiratory Tract Infections

Reading D: An overview and management of Osteoporosis

Reading E: Full Body Stretching Routine

Reading F: The Stroke Survivor

Reading G: Convulsions in Children

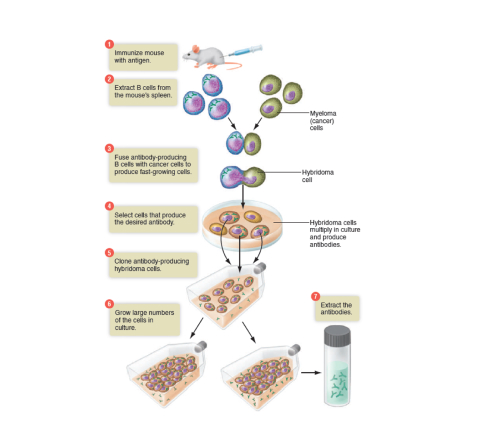

Reading H: Medical Assistance in the War Against Pathogens

Reading I: Cardiovascular Risk and Obesity

Reading J: Sleep Matters

Important note to students:

The Readings contained in this Readings are a collection of extracts from various books, articles and other publications. The Readings have been replicated exactly from their original source, meaning that any errors in the original document will be transferred into this Book of Readings. In addition, if a Reading originates from an American source, it will maintain its American spelling and terminology. IAH is committed to providing you with high quality study materials and trusts that you will find these Readings beneficial and enjoyable.

Habrat, D. (2022). How to do the Heimlich Manoeuvre in the conscious adult of child. Merck & Co.

The Heimlich manoeuvre (abdominal thrusts) is a rapid first-aid procedure to treat choking due to upper airway obstruction by a foreign object, typically food or a toy. Chest thrusts and back blows can also be used if needed.

Indications for a Heimlich Manoeuvre

- Choking due to severe upper airway obstruction due to a foreign object (signalled by inability to speak, cough, or breathe adequately)

The Heimlich and other manoeuvres should be used only when the airway obstruction is severe, and life is endangered. If the choking person can speak, cough forcefully, or breathe adequately, no intervention is required.

Contradictions to Heimlich Manoeuvre

Absolute contraindications

- Age < 1 year is a contraindication to the Heimlich manoeuvre

Relative contraindications

- Children < 20 kg (45 lb; typically, < 5 years) should receive only moderate pressure thrusts and back blows.

- Obese patients and women in late pregnancy should receive chest thrusts instead of abdominal thrusts.

Complications of Heimlich Manoeuvre

- Rib injury or fracture

- Internal organ injury

Additional considerations for Heimlich manoeuvre

- These rapid first aid procedures are done immediately wherever the person is choking.

- Use of significant, abrupt force is appropriate for these manoeuvres. However, clinical judgment is needed to avoid excessive forces that can cause injury.

- The Heimlich manoeuvre is well-known and widely used. However, chest thrusts and back blows may produce higher airway pressures. More than one manoeuvre may be used in succession if the initial manoeuvre fails to remove the obstructing object.

Relevant Anatomy for Heimlich Manoeuvre

- The epiglottis usually protects the airway from aspiration of foreign objects (e.g., food).

- Aspirated objects may be above or below the vocal cords.

Positioning for Heimlich Manoeuvre

- In general, the rescuer stands behind the choking person or kneels behind a child.

Step-by-Step Description of Heimlich Manoeuvre

Determine if there is severe airway obstruction

- Look for signs such as inability to speak, cough, or breathe adequately.

- Look for hands clutching the throat, which is the universal distress signal of severe airway obstruction.

- Ask: “Are you choking?”

- If the person can speak and breathe, encourage them to cough but do not initiate airway clearance manoeuvres; instead, arrange medical evaluation.

- If the choking person nods yes or cannot speak, cough, or breathe adequately, that suggests severe airway obstruction and the need for airway clearance manoeuvres.

Treat the choking conscious adult or child

- Stand directly behind the choking adult or kneel behind a child.

- Begin with abdominal thrusts for people who are not pregnant or obese; do chest thrusts for obese patients and women in late pregnancy.

- Alternate between sets of abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuverer), chest thrusts, and back blows as needed to relieve the obstruction.

- Continue until obstruction is removed or advanced airway management is available.

- If the person loses consciousness, start cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). After each set of chest compressions, look inside the patient's mouth before giving rescue breaths and remove any visible obstruction that can be reached. Do not do blind finger sweeps.

Abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuverer):

- Encircle the patient’s midsection with your arms.

- Clench one fist and place it midway between the umbilicus and xiphoid.

- Grab the fist with the other hand (see figure Abdominal thrusts with victim standing or sitting).

- Deliver a firm inward and upward thrust by pulling with both arms sharply backward and upward.

- Rapidly repeat the thrust 6 to 10 times as needed.

Abdominal thrusts with victim standing or sitting (conscious)

Chest thrusts:

- Encircle the patient’s midsection with your arms.

- Clench one fist and place it on the lower half of the sternum.

- Grab the fist with the other hand.

- Deliver a firm inward thrust by pulling both arms sharply backward.

- Rapidly repeat the thrust 6 to 10 times as needed.

Back blows:

- Wrap one arm around the waist to support the patient's upper body; small children can be laid across your legs.

- Lean the person forward at the waist, about 90 degrees if possible.

- Using the heel of your other hand, rapidly deliver 5 firm blows between the person's shoulder blades.

Aftercare for Heimlich Manoeuvre

- Patients with any symptoms remaining after foreign body removal should have a medical evaluation.

Warnings and Common Errors for Heimlich Manoeuvre

- These manoeuvres should not be done if the choking person can speak, cough forcefully, or breathe adequately.

- In obese patients and women in late pregnancy, chest thrusts are used instead of abdominal thrusts.

Tips and Tricks for Heimlich Manoeuvre

- The Heimlich maneuverer may induce vomiting. Although vomiting may assist in dislodging a tracheal foreign body, it does not necessarily mean that the airway has been cleared

Lehtinen, P., Martin, M., Seppa, M., & Toro, T. (2018). Breathing as a tool for self-regulation and self-reflection. Routledge Publishing.

Introduction

Psychophysical breathing exercises can also be used for problems with under arousal in depressed and exhausted people. Depression is not usually the main reason for seeking psychophysical breathing therapy but, in our experience, breathing therapy has reduced symptoms of depression. Williams, Teasdale, Segal, and Kabat-Zinn (2007) have also successfully applied psychophysical methods for the treatment of depression.

Observations concerning breathing and other physical sensations are important because they help to guide our activity and seeking of balance if we know how to utilise the information. We can observe which part of our body feels warm or tense and whether our breathing is calm, shallow, or vigorous. Such observations improve our self-knowledge and ability for self-reflection. Donald W. Winnicott (1951, 1987), an English paediatrician and psychoanalyst, has emphasised the significance of such experiences: a true experience of the self is based precisely on physical sensations, on the body being alive as experienced through heartbeat and breathing. Therefore, improving the ability to observe both physical sensations and changes in mood is pivotal in psychophysical breathing therapy. Participants pay attention to what is happening in their bodies and create space for experiences. Through self-compassion and reassurance, they learn not to let their sensations lead to impulsive panicking. Such a stance will help the person to simply wonder about his experiences instead of being frightened by them. Kabat-Zinn describes a similar way of working in his books (1994, 2013).

Stress

Positive Stress

Stress is a factor that triggers many disturbances. The creator of the stress concept, endocrinologist Hans Selye (1974), considers stress as the body’s general response to any challenge, whether positive or negative, physical or mental. Selye calls positive stress eustress (becoming more alert) and negative stress distress (becoming overwhelmed). Being positive, eustress is experienced as making the body and mind more alert. This makes our potential available for use; we want to push ourselves voluntarily, learn new things, and put everything we can into what we are doing. We learn such curiosity, enthusiasm, and seeking of challenges in interactions where our abilities and potential are recognised, and we are urged and encouraged to face new issues. We receive support in our learning as necessary, and later enjoy the feeling of succeeding on our own.

Characteristically for eustress, we experience the level of stress as appropriate, that is, not an excessive burden on the body or mind. Another characteristic of eustress is that we can utilise our resources to reduce stress. People experiencing positive stress are typically able to react rapidly to the stress and seek the necessary changes instead of pushing themselves and clenching their teeth to cope. These skills strengthen the ability to cope with stress, which will protect against negative stress. Excessive stress consumes our resources without resolving the stress-inducing situation. In real life, eustress and distress often vary and situations may involve both threatening and positive challenges. Our assessment of which type of stress we are experiencing depends on our previous experiences and our attitude to them.

Bodily stress can be triggered by many physical stimuli, such as heat, cold, pain, thirst, low blood sugar, or disease, as well as by mental stress. Triggers of mental stress, on the other hand, may be more difficult to define and there is no comprehensive description available, so far, for this complex psychobiological phenomenon. Nevertheless, many causes of mental stress are familiar to modern people: challenging relationships, excessive stimuli (noise, traffic, being bombarded with information from TV and information technology, background music), rush, time pressure, a competitive, performance-centred lifestyle, lack of sleep, etc. People often maintain stress by demanding a lot from themselves or by repeatedly putting the needs of others before their own. Stress thus means that we assess the demands on us and our resources and find them to be out of balance. Stress is a natural reaction to trying to cope with a physical or mental burden. The problem is that people will not always listen to the warning signs and try to cut down on stressors soon enough.

These traffic lights can be used to distinguish between positive stress and stress that is becoming negative:

Negative stress

or a while, stress may help us to cope with demands. However, if it becomes prolonged or if we need to face several stressors at the same time, the risk of various physical and mental diseases will increase. Anyone exposed to stressors for a long time is in a constant fight or flight state without the chance for recovery. In that case, stress-related cortisol secretion and long-term activation of the sympathetic nervous system increase. Constant secretion of stress hormones has detrimental, cumulative long-term effects on various organ systems. It weakens the immune system, increases blood coagulation, destroys neurons in the hippocampus, impairs glucose metabolism, affects the cardiovascular system, and disturbs mood, memory, and ageing of brain tissue.

The interaction between stress and disease works in two directions—stress contributes to the outbreak of many diseases, and disease causes stress, reduces available resources, and thus impairs stress tolerance (Korkeila, 2006; McEwen, 1998).The relation between breathing and stress also works in two directions. Increasing stress causes imbalanced breathing. In prolonged stress, overactivated breathing persists. We rarely come to think of how much stress imbalanced breathing causes. Constantly imbalanced breathing causes disturbances that are either biochemical in nature or result from respiratory mechanics. When a person receives training in breathing, she may be astonished at the difference made by her improved breathing pattern: she no longer feels tired but more alert and relaxed. Calming down of breathing thus notably promotes stress control, both by calming down the mind and by influencing physical stress responses.

Activation of rigid, persistently negative conditioned reactions is typical for prolonged stress. Such reactions may make a person continue working with clenched teeth and performing even after depleting his resources or, alternatively, may make him passive and inactive. Some people try to cope by performing and trying to keep everything firmly under their control. The problem is that one cannot control a living connection to oneself, others, and the rest of the world. Repeated experiences of not being able to influence stressors may also lead to learned helplessness (Seligman, 1991). In that case a person no longer tries to influence stressors even if he has the chance to do so. Learned helplessness has severe effects on the body. It has been found that what is destructive for the immune system is precisely a prolonged experience of lack of control, not the stress as such. The very thought of “You can always breathe” will protect us from stress and create an impression of being able to influence our situation. Stress may sometimes have insidious effects: it may gnaw at our immunity even if we do not realise, we are stressed. In addition, a pessimist’s way of life often involves neglecting oneself: it is no use taking care of yourself because things will turn out badly anyway. Learned helplessness will thus lead to increased malaise and stress. On the other hand, a small amount of pessimism (realism) is not detrimental and may even protect us from trouble.

Some individuals react to helplessness by attempting to replace it by aggressive fighting. In psychophysical breathing therapy we often see people finding it hard to set boundaries to protect themselves from excessive stress. In addition, they often have problems in expressing disagreement or anger. They may not dare at all to express feelings that they feel are forbidden, and may thus also avoid any use of physical strength associated with such feelings. Caution may become the pervasive hallmark of life. Alternatively, disappointment or disagreement may even be expressed too forcefully, violating other people’s boundaries. Psychophysical breathing therapy can be used to seek constructive solutions for difficulties in self-regulation and self-expression. Assertive expression taking one’s own rights and needs into account can be learned in interaction in an environment allowing feelings of being tired and limited.

Physical exercise, breathing, and recovery

Of the most common means of managing stress, exercise is considered a rather effective way of unloading its burden. It has extensive effects on mind and body and works rapidly—starting exercise may show as improved well-being within as little as a fortnight (Korkeila, 2006). However, one mustn’t overdo it. Excessive exercising may maintain stress instead of alleviating it. Overtraining in athletes may thus represent a combination of exhaustion and imbalanced breathing. Following exercise recommendations is not simple for all stressed people. For people tending to hyperventilate, physical exercise may be unpleasant because it increases symptoms related to imbalanced breathing and the resulting alkalinity of the blood.

Over breathing during exercise also increases muscle tension and the person’s condition will thus not improve because rest and recovery remain insufficient. He may need to learn to breathe calmly before starting to exercise. For many people unaware of their breathing problems and muscle tension, combining the mindset and methods of psychophysical breathing therapy with exercise instruction would thus serve to prevent problems and help them become more balanced. In sports medicine, attention has been directed to how nasal breathing may promote performance and health even during strenuous exertion (cf. page 29). For people exercising actively, breathing exercises may provide the chance to learn to stop and to acquire patience. Psychophysical breathing therapy will also provide competing athletes with the chance to balance stress and tension (Tuomola, 2012).A study by van Dixhoorn in patients with myocardial infarction (van Dixhoorn & Duivenvoorden, 1999) showed that physical performance as part of the patients’ rehabilitation improved when breathing therapy was added to the rehabilitation programme. A five-year follow-up also showed improvement in the patients’ cardiac health as measured by physiological parameters, and a decrease in the prevalence of cardiac diseases and in health care costs. In the Netherlands, breathing therapy has been adopted as a part of rehabilitation of patients with myocardial infarction.

Psychophysical breathing exercises could be utilised more in day care centres, at schools, and in physical exercise for children, as illustrated by the following examples:

In a day care centre, children were calmed down by using mental images while they were lying on a mattress. Another group of children learned to calm each other down by kneading each other’s backs with the palms of their hands. A teacher, who had worked with her breathing in her own therapy, said that she learned to calm down a restless secondary school class by her own breathing: “Previously I might have raised my voice, now I just breathe. I have found it to be much more effective than getting all worked up.

Getting support from one’s relatives is another important means of managing stress. Throughout life, intimacy, touching, calming down together, sharing, and putting things into perspective are among the most important means of restoring balance. In addition, various hobbies, such as singing, gardening, or taking part in cultural activities will help. One factor connecting all these is calming down of breathing. We may not be aware of it, but when we are feeling safe, calm, experiencing pleasure, touching, another person’s presence, warmth, having time for ourselves, easing up, our breathing gets deeper and calmer. Or on the conscious level: by breathing calmly we can find our way out of the cycle of stress.

Many helpers think it is their task to support people in achieving better stress tolerance and improved performance. In psychophysical breathing therapy, we think in the opposite way: we do not want to teach people to tolerate more stress but to lower their tolerance of stress by reacting to stressors more rapidly. It is not always about reducing the amount of what we do but learning calmer and less demanding attitudes. Self-compassion is the mental equivalent of soothing breathing.

Pain

Significance and alleviation of pain

The capacity to feel pain is a life-preserving ability that protects us from dangers. Everyone knows from experience what their reaction is to sudden pain: immediate inhalation followed by intensive exhalation. If this is not followed by action, over breathing may ensue. Modern analgesics have brought great pain relief. In acute pain, sufficient analgesic medication makes you feel better in many ways, promotes recovery by facilitating movement, and prevents the pain from becoming chronic. But in addition to medication, other means are needed if pain is severe and long lasting. Our most significant means of regulating pain is associated with an interactive relationship that is calming, nurturing, and comforting and allows us to soothe ourselves later on when experiencing pain. Acute, severe pain often involves imbalanced breathing, accelerated breathing or holding one’s breath, or both. In connection with a painful procedure, experienced nurses and doctors may tell the patient to “breathe calmly” or to “remember to breathe”. People often push against pain, trying to put it out of their minds. If you suffer from pain, people often say “forget it” or “ignore it”. Such phrases do contain a partial truth: directing your attention away from the pain will help you to cope somewhat. Denial, again, usually increases the experience of pain and resulting stress. Various types of relaxation, breathing, mindfulness, and mental training have been shown to be useful in the regulation of pain.

Over breathing is a useful impulse when you are in sudden pain. It will have been expedient in earlier stages of evolution, in particular since it speeds up the ability for fight or flight, as necessary. In addition, over breathing is associated with the alleviation of acute pain. In ritual ceremonies and in connection with torture, over breathing is often utilised to alleviate pain. Breathing therapy is naturally quite significant in the physiotherapy of patients who have been tortured (Hough, 1992). In an acute situation, over breathing acts similarly on both physical and mental pain, having an anaesthetic effect on both. However, if over breathing continues, pain will be experienced as more severe.

I underwent a painful procedure. I had not realised that it would feel so unpleasant and did not know I could prepare for it by taking preventive analgesic medication. In the actual situation, my breathing was first blocked for several seconds and then accelerated for a long time. I felt severe pain several hours after the procedure. A few years later the procedure was repeated. I then noticed the first changes in my breathing already when thinking about making the appointment. I took preventive analgesics for the procedure. In the waiting room I concentrated on soothing myself by breathing slowly. The procedure was painful, but this time pain didn’t take control over me because I breathed evenly, concentrating on long, calm exhalation. I was surprised to see the significance of breathing for pain control, even though I did have similar experience from giving birth. I just had not known how to adapt those skills to a different situation.

How pain becomes chronic, and the consequences

When pain is prolonged and becomes chronic, a series of mental and bodily conditioning reactions begin. These maintain a vicious circle of pain. Long-term pain may develop if the source of pain cannot be eliminated or because physical and emotional pain is processed in the same brain area and the source of pain is thus displaced (Eisenberger, 2012). Somatic pain may lead to mental pain, depression, or vice versa. Depression in connection with chronic pain may be due to losses associated with pain and impaired functional ability. The difficulty of constructive processing of the experienced loss leads to “displaced sorrow”, that is, depression.

If the pain signal is not eliminated, the person becomes sensitised and conditioned to it. The signal becomes more intense in order to make her eliminate the source of pain, for example by changing her behaviour. A “pain memory” is created, that is, pain is experienced even in the absence of the original stimulus (Eisenberger, 2012). In that case, neural pathways suppressing pain do not act normally. It has been found that people with such inaccurate pain often have disturbances in their attachment. They may not have been able to assimilate “the other” soothing their emotional and physical pain and may thus even later more easily be overwhelmed by an uncontrolled experience of pain.

The experience of pain activates unconscious internal interactive models. This is reflected in, for example, how we seek help and our attitudes to ourselves and our symptoms. We learn how to react to pain in interaction. We assimilate how our parents reacted when they themselves experienced pain or how they reacted to us when we hurt ourselves or fell ill. If we have become used to thinking primarily of others and putting our own needs second, we dare not ask for help in dealing with pain because we assume others will need help even more. The ability to reach the internal soothing other is central for regulating the experience of pain, keeping calm, and soothing and comforting oneself. Self-compassion is like a kind, internal caress to soothe the pain.

Breathing, posture, and pain

If a person breathes chronically with his upper chest, his posture will gradually change, his head and shoulders moving forward. Such a change in posture may occur for physical, ergonomic, or mental reasons, or all three simultaneously. Imbalanced breathing may be one reason for stress symptoms in people working with a poor posture on a computer. If the head is pushed forward and the auxiliary breathing muscles are subject to excessive strain, the posture will also disturb the dynamics of the muscles around the jaw joint. This will lead to occlusion problems and cause headaches (Bartley & Clifton-Smith, 2006; Hruska, 1997).

In a study with college students involving cell phone text messaging, Lin and Peper (2009) found that all twelve subjects showed significant increases in breathing and heart rate as well as in skin conductance when texting. Most of them also felt hand and neck pain. One wonders what their health will be like after fifty years! Changing of conditioned movement patterns and working positions will take time because a change also needs to take place in the person’s relationship to his body and body language. The relationship may have become very controlling and negative or passive and evasive of responsibility. If so, a change of position will require a therapeutic relationship, while ergonomic guidance alone, for example, will not be sufficient. For a permanent change, the patient needs encouragement to increase her ability to observe herself. She may then learn to become conscious of herself in relation to gravity and her vertical position and to breathe appropriately in various situations. The results are often good if the patient sees the need for change herself:

After the breathing school I felt the need to improve the quality of my life in other ways too. I took a course in Alexander technique and consequently lay down on the floor daily with a pile of books under my head. In addition, I started neck and shoulder exercise classes. After a few months, I had an X-ray of my neck taken because I knew there was some erosion there. I had indeed taken good care of my neck: there was a wedge-shaped opening visible between vertebrae that showed that my neck had been tilted forward and had now become straighter. It was now important to continue taking good care of the condition of my muscles. At about that time, I had a wonderful experience: I saw that the streets in my hometown were really beautiful. I had not noticed their impressive proportions. My new posture really felt good, and the change was not only physical. I still sometimes have neck pain but now it serves to remind me to hold my head up!

Pain and muscle tension

Little is known about long-term imbalanced breathing associated with prolonged pain and there have been few studies. Patients with chronic pain often breathe with their upper chest, using their auxiliary breathing muscles more. Auxiliary breathing muscles are mainly meant for short-term use for movement and maintenance of posture. Prolonged use leads to changes in the muscles, causing pain and reducing muscle strength. Breathing becomes shallow and focused on inhalation. Laboratory studies have shown that patients with chronic pain have a low exhaled air carbon dioxide content, that is, their bodies are in a state of physiological hyperventilation (see Wilhelm, Gevirtz, & Roth, 2001). In practice, we have found patients with chronic pain to have superficial, imbalanced breathing.

Many of our patients with breathing symptoms suffer from severe, vague pain in the upper body. They are often worried by the symptoms and associate them with cardiac symptoms. Health care professionals do not necessarily understand the origin of such pain, either. The pain may be dismissed as being due to tension, and its connection with imbalanced breathing may not be explored. In many cases, muscle pain in the upper body is due to long-term inappropriate use of auxiliary breathing muscles.

Muscle pain was not the first possibility to occur to me. Particularly as muscle pain is mainly considered to be due to stress or tension. This was quite intense chest pain. I asked my husband to press at the point of pain, and he had to press really hard. Gradually the pain subsided. The symptoms were often quite vague: once the right side of my face got sort of paralysed for a while. Now I know this was related to over breathing.

A classic test by Friedman from 1945 supports the connection between the use of breathing muscles and muscle pain. A tight bandage was placed around the abdomen and lower ribs of healthy subjects. They started experiencing shortness of breath and, in a couple of days, developed chest pain that grew worse on exertion. The pain stopped when the bandage was removed. Another group of subjects had chest pain to begin with but no cardiac disease. Bandages were placed around their chests so that they could not breathe heavily using their chest muscles. The pain subsided but recurred after removing the bandage when the subjects again started using their upper chest muscles instead of the diaphragm for breathing.

We have successfully applied the phenomena described in the test in psychophysical breathing therapy. Placing bean bags of two or three kilograms on the chest helps to move breathing with auxiliary muscles downward. In many people, the weight and the resulting experience of body boundaries and of getting stronger increase the feeling of security. Work done by auxiliary breathing muscles between the ribs and in the neck area decreases. These effects together help increase the person’s awareness of the movement in diaphragmatic-abdominal breathing. Bean bags are frequently used in our groups, and the meaningful experience has motivated many of our patients and students to make bags for themselves to calm down their breathing at home. Their minds then also calm down. We think that the bean bag also acts as a transitional object activating and strengthening the ability to calm down and thus enhancing the feeling of security.

A therapist lent a patient who had suffered from anxiety since his childhood heavy bean bags to take home. After three months, the patient brought up the use of the bags. He said he had used them every night when going to bed. He said he fell asleep faster, slept more peacefully, had more peaceful and interesting dreams, and no longer had constant tension and pain in the neck and shoulder region, a heavy feeling in his chest or a lump in his throat. Meanwhile, of course, his situation had been discussed, too, but he himself felt that the use of the heavy bean bags had gradually changed his way of using his upper body muscles.

Muscle tension may have both physical and mental causes. The mental causes are discussed in many connections in this book. There may be many kinds of physical stressors: congenital ones as well as ones due to musculoskeletal disease, trauma, or ageing. Stressors may also be associated with overweight or strain on the body due to working positions, sports, or the use of mobile devices. Imbalanced breathing may persist, become conditioned, even if the original stressor no longer exists. Long-term use of auxiliary breathing muscles may also cause pain through blood vessel or nerve impingement. Chain reaction due to breathing predominantly with auxiliary breathing muscles in the long term

The first reaction is increased muscle tension: this affects muscles, muscle fasciae, tendons, cartilage, joints, and ligaments Muscle metabolism gradually changes: constant contraction of muscles and fasciae is associated with lack of oxygen, inflammation, or irritation Decreased flexibility of joints and ligaments further hinders breathing Movements change Trigger points are formed Nervous overreaction develops This leads to decreased elasticity of the lungs, which further hinders breathing This results in increased susceptibility to, for example, many musculoskeletal diseases.

Development of trigger or reflection points is one of the physiological phenomena related to inappropriate long-term use of auxiliary breathing muscles that probably explains many peculiar pain symptoms. Trigger points are defined areas in the tissue that can be stimulated to produce pain distant from the point of stimulation. Pain caused by trigger points due to overuse of auxiliary breathing muscles may occur extensively in the body. For example, pain due to tightness of muscles in the throat and neck region may be felt in the forehead, eye and ear regions, jaw joints, maxillary sinuses and teeth, as a lump in the throat, or even as tingling in the fingers.

Trigger points are a phenomenon known in medicine but in health care they are only rarely linked with respiratory problems through overuse of muscles. Chaitow, an osteopath (2002, pp. 99–104), Bartley, an ear, nose, and throat surgeon, and Clifton-Smith, a physical therapist (2006), regard trigger phenomena as very significant sequelae of prolonged imbalanced breathing. (See also Richter & Hebgen, 2008.)

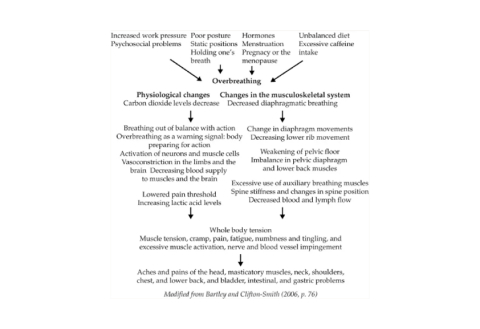

The following figure describes the complex connections between muscle pain and breathing.

Psychophysical treatment of muscle pain

Many professionals working with muscle problems, such as physiotherapists, osteopaths, and voice massage therapists, pay attention to breathing problems and deal with their consequences in muscles, muscle fasciae, and joints. Breathing exercises, relaxation, and muscle manipulation change muscle dynamics and normalise the function of pain pathways. For the effects of treatment to persist, it would be important for people with chronic symptoms to have the chance of participating in psychophysical breathing therapy. Patients with breathing problems may need breathing therapy, muscle and joint manipulation, psychotherapy, and medication. The combination of various types of treatment and the correct timing of each treatment are decisive for success.

In psychophysical breathing therapy, people are taught a new kind of approach to pain and tension: calm breathing will relieve the symptoms. Directing the attention to breathing may help the patient to concentrate on other things. The idea of an internal soothing caress will help to relieve the pain and muscle tension and comfort the pained mind. When the patient learns to breathe calmly despite the pain, the chances of recovery will be notably improved. He may learn to recognise and study pain, bodily tension, and restlessness through breathing. He learns to exist with the pain instead of avoiding it. He may also use other images to influence his experience, such as imagining that he is breathing into the pain and visualising the pain leaving the body as he exhales.

Thomas, M., & Bomar, P. A. (2022). Upper respiratory tract infection. StatPearls Publishing.

Introduction

A variety of viruses and bacteria can cause upper respiratory tract infections. These cause a variety of patient diseases including acute bronchitis, the common cold, influenza, and respiratory distress syndromes. Defining most of these patient diseases is difficult because the presentations connected with upper respiratory tract infections (URIs) commonly overlap and their causes are similar. Upper respiratory tract infections can be defined as self-limited irritation and swelling of the upper airways with associated cough with no proof of pneumonia, lacking a separate condition to account for the patient symptoms, or with no history of COPD/emphysema/chronic bronchitis. [1] Upper respiratory tract infections involve the nose, sinuses, pharynx, larynx, and the large airways.

Etiology

Common cold continues to be a large burden on society, economically and socially. The most common virus is rhinovirus. Other viruses include the influenza virus, adenovirus, enterovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus. Bacteria may cause roughly 15% of sudden onset pharyngitis presentations. The most common is S. pyogenes, a Group A streptococcus.

Risk factors for a URTI

- Close contact with children: both day-cares and schools increase the risk of URI.

- Medical disorder: People with asthma and allergic rhinitis are more likely to develop URI.

- Smoking is a common risk factor for URI.

- Immunocompromised individuals including those with cystic fibrosis, HIV, use of corticosteroids, transplantation, and post-splenectomy are at high risk for URI.

- Anatomical anomalies including facial dysmorphic changes or nasal polyposis also increase the risk of URI.

Epidemiology

Across the country, URIs are one of the top three diagnoses in the outpatient setting. Estimated annual costs for viral URI, not related to influenza, exceeds $22 billion. [2] Upper respiratory tract infections account for an estimated 10 million outpatient appointments a year. Relief of symptoms is the main reason for outpatient visits amongst adults during the initial couple weeks of sickness, and a majority of these appointments result with physicians needless writing of antibiotic prescriptions. Adults obtain a common cold around two to three times yearly whereas paediatrics can have up to eight cases yearly. Fall months see a peak in incidence of common cold caused by the rhinovirus. Upper respiratory tract infections are accountable for greater than 20 million missed days of school and greater than 20 million days of work lost, thus generating a large economic burden.

Pathophysiology

A URTI usually involves direct invasion of the upper airway mucosa by the organism. The organism is usually acquired by inhalation of infected droplets. Barriers that prevent the organism from attaching to the mucosa include:

- the hair lining that traps pathogen,

- the mucus which also traps organisms

- the angle between the pharynx and nose which prevents particles from falling into the airways and

- ciliated cells in the lower airways that transport the pathogens back to the pharynx.

The adenoids and tonsils also contain immunological cells that attack the pathogens.

Influenza

The incubation period for influenza is 1 to 4 days, and the time interval between symptom onset is estimated to be 3 to 4 days. Viral shedding can occur 1 day before the onset of symptoms. It is believed that influenza can be transferred among humans by direct contact, indirect contact, droplets, or aerosolization. Short distances (<1 meter) are generally required for contact and droplet transmission to occur between the source person and the susceptible individual. Airborne transmission may occur over longer distances (>1 m). Most evidence-based data suggest that direct contact and droplet transfer are the predominant modes of transmission for influenza.

Common Cold

The pathogens are responsible for causing the common cold include rhinovirus, adenovirus, parainfluenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, enterovirus, and coronavirus. The rhinovirus, a species of the Enterovirus genus of the Picornaviridae family, is the most common cause of the common cold and causes up to 80% of all respiratory infections during peak seasons. Dozens of rhinovirus serotypes and frequent antigenic changes among them make identification, characterization, and eradication complex. After deposition in the anterior nasal mucosa, rhinovirus replication and infection are thought to begin upon mucociliary transport to the posterior nasopharynx and adenoids. As soon as 10 to 12 hours after inoculation, symptoms may begin. The mean duration of symptoms is 7 to 10 days, but symptoms can persist for as long as 3 weeks. Nasal mucosal infection and the host's subsequent inflammatory response cause vasodilation and increased vascular permeability. These events result in nasal obstruction and rhinorrhoea whereas cholinergic stimulation prompts mucus production and sneezing.

History and Physical

Acute upper respiratory tract infections include rhinitis, pharyngitis, tonsillitis, and laryngitis. Symptoms of URTIs commonly include:

- Cough

- Sore throat

- Runny nose

- Nasal congestion

- Headache

- Low-grade fever

- Facial pressure

- Sneezing

- Malaise

- Myalgias

The onset of symptoms usually begins one to three days after exposure and lasts 7–10 days, and can persist up to 3 weeks.

Evaluation

The presence of classical features for rhinovirus infection, coupled with the absence of signs of bacterial infection or serious respiratory illness, is sufficient to make the diagnosis of the common cold. The common cold is a clinical diagnosis, and diagnostic testing is not necessary. When testing for influenza, obtain specimens as close to symptom onset as possible. Nasal aspirates and swabs are the best specimens to obtain when testing infants and young children. For older children and adults, swabs and aspirates from the nasopharynx are preferred. Rapid strep swabs can be used to rule out bacterial pharyngitis, which could help decrease number of antibiotics being prescribed for these infections.

Treatment/Management

The goal of treatment for the common cold is symptom relief. Decongestants and combination antihistamine/decongestant medications can limit cough, congestion, and other symptoms in adults. Avoid cough preparations in children. H1-receptor antagonists may offer a modest reduction of rhinorrhoea and sneezing during the first 2 days of a cold in adults. First-generation antihistamines are sedating, so advise the patient about caution during their use. Topical and oral nasal decongestants (i.e., topical oxymetazoline, oral pseudoephedrine) have moderate benefit in adults and adolescents in reducing nasal airway resistance. Evidence-based data does not support the use of antibiotics in the treatment of the common cold because they do not improve symptoms or shorten the course of illness. There is also a lack of convincing evidence supporting the use of dextromethorphan for acute cough.

According to a Cochrane Review, vitamin C used as daily prophylaxis at doses of =0.2 grams or more had a "modest but consistent effect" on the duration and severity of common cold symptoms (8% and 13% decreases in duration for adults and children, respectively). When taken therapeutically after the onset of symptoms, however, high-dose vitamin C has not shown clear benefit in trials.

Early antiviral treatment for influenza infection shortens the duration of influenza symptoms, decreases the length of hospital stays, and reduces the risk of complications. Recommendations for the treatment of influenza are updated frequently by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention based on epidemiologic data and antiviral resistance patterns. Give antiviral therapy for influenza within 48 hours of symptom onset (or earlier), and do not delay treatment for laboratory confirmation if a rapid test is not available. Antiviral treatment can provide benefit even after 48 hours in pregnant and other high-risk patients.[12]

Vaccination is the most effective method of preventing influenza illness. Antiviral chemoprophylaxis is also helpful in preventing influenza (70% to 90% effective) and should be considered as an adjunct to vaccination in certain scenarios or when vaccination is unavailable or not possible. Generally, antiviral chemoprophylaxis is used during periods of influenza activity for (1) high-risk persons who cannot receive vaccination (due to contraindications) or in whom recent vaccination does not, or is not expected to, afford a sufficient immune response; (2) controlling outbreaks among high-risk persons in institutional settings; and (3) high-risk persons with influenza exposures. [13]

Go to:

Differential Diagnosis

- Common Cold

- Allergic rhinitis

- Sinusitis

- Tracheobronchitis

- Pneumonia

- Influenza

- Atypical Pneumonia

- Pertussis

- Epiglottitis

- Streptococcal Pharyngitis/Tonsillitis

- Infectious Mononucleosis

Go to:

Prognosis

URI are common during the winter season and for the most part, are benign, but they can seriously affect the quality of life for a few weeks. A few individuals may develop pneumonia, meningitis, sepsis, and bronchitis. Each year, there are isolated cases of death reported from a URI. Time off work and school is very common. In addition, patients spend billions of dollars on worthless remedies. There is little evidence that any treatment actually shortens the duration of a viral URI. Even the vaccine only works in 40-60% of individuals, at best.

Go to:

Complications

Complications of upper respiratory tract infections are relatively rare, except with influenza. Complications of influenza infection include primary influenza viral pneumonia; secondary bacterial pneumonia; sinusitis; otitis media; coinfection with bacterial agents; and exacerbation of preexisting medical conditions, particularly asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pneumonia is one of the most common complications of influenza illness in children and contributes significantly to morbidity and mortality.

Go to:

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Upper respiratory tract infections are one of the most common illnesses that healthcare workers will encounter in an outpatient setting. The infection may vary from the common cold to a life-threatening illness like acute epiglottitis. Because of the diverse causes and presentation, upper respiratory tract infections are best managed by an interprofessional team.

The key is to avoid over-prescribing of antibiotics but at the same time not missing a life-threatening infection. Nurse practitioners who see these patients should freely communicate with an infectious disease expert if there is any doubt about the severity of the infection. The pharmacist should educate the patient on URI and to refrain from overusing unproven products.

Similarly, the emergency department physician should not readily discharge patients home with antibiotics for the common cold. Overall, upper respiratory tract infections lead to very high disability for short periods. Absenteeism from work and schools is common; in addition, the symptoms can be annoying and extreme fatigue is the norm. Patients should be encouraged to drink ample fluids, rest, discontinue smoking and remain compliant with the prescribed medications.[14]

Nursing can monitor the patient's condition and symptoms, counsel on medication compliance, and report any concerns to the clinicians managing the case. Interprofessional cooperation is key to good outcomes. [Level 5]

Finally, clinicians should urge patients to get vaccinated before the flu season. While the vaccine may not decrease the duration of the infection, the symptoms are much less severe.

The outcomes in most patients are good, particularly with the interprofessional team approach. [Level 5]

Sozen, T., Ozisik, L., & Basaran, C. N. (2017). An overview and management of osteoporosis. European Journal of Rheumatology.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a disease that is characterized by low bone mass, deterioration of bone tissue, and disruption of bone microarchitecture: it can lead to compromised bone strength and an increase in the risk of fractures. Osteoporosis is the most common bone disease in humans, representing a major public health problem. It is more common in Caucasians, women, and older people. Osteoporosis is a risk factor for fracture just as hypertension is for stroke. Osteoporosis affects an enormous number of people, of both sexes and all races, and its prevalence will increase as the population ages. It is a silent disease until fractures occur, which causes important secondary health problems and even death. It was estimated that the number of patients worldwide with osteoporotic hip fractures is more than 200 million. It was reported that in both Europe and the United States, 30% women are osteoporotic, and it was estimated that 40% post-menopausal women and 30% men will experience an osteoporotic fracture in the rest of their lives.

Osteoporosis is also an important health issue in Turkey, because the number of older people is increasing. The incidence rate for hip fracture increases exponentially with age in all countries as well as in Turkey, which is evident in the FRACTURK study. It was estimated that around the age of 50 years, the probability of having a hip fracture in the remaining lifetime was 3.5% in men and 14.6% in women. Bone tissue is continuously lost by resorption and rebuilt by formation; bone loss occurs if the resorption rate is more than the formation rate. The bone mass is modelled (grows and takes its final shape) from birth to adulthood: bone mass reaches its peak (referred to as peak bone mass (PBM)) at puberty; subsequently, the loss of bone mass starts. PBM is largely determined by genetic factors, health during growth, nutrition, endocrine status, gender, and physical activity. Bone remodelling, which involves the removal of older bone to replace with new bone, is used to repair microfractures and prevent them from becoming macro fractures, thereby assisting in maintaining a healthy skeleton. Menopause and advancing age cause an imbalance between resorption and formation rates (resorption becomes higher than absorption), thereby increasing the risk of fracture.

Certain factors that increase resorption more than formation also induce bone loss, revealing the microarchitecture. Individual trabecular plates of bone are lost, leaving an architecturally weakened structure with significantly reduced mass; this leads to an increased risk of fracture that is aggravated by other aging-associated declines in functioning. Increasing evidence suggests that rapid bone remodelling (as measured by biochemical markers of bone resorption or formation) increases bone fragility and risk of fracture. There are factors associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis-related fractures. These include general factors that relate to aging and sex steroid deficiency, as well as specific risk factors such as use of glucocorticoids (which cause decreased bone formation and bone loss), reduced bone quality, and disruption of microarchitectural integrity. Fractures result when weakened bone is overloaded, often by falls or certain daily chores.

Clinical Consequences

Clinical evaluation Osteoporosis has been mislabelled as a women’s disease by the public, but it affects men, too: young men are afflicted by it, which usually goes undiagnosed until a fracture brings the patient to a doctor. However, delayed interventions are usually unsuccessful. The diagnosis of osteoporosis is never taken as primary osteoporosis without ruling out the secondary causes. A good history and physical examination of the patient always reveal certain clues about the presence of another disease: certain special laboratory evaluations might be needed to rule out other responsible diseases.

Approach to a patient with osteoporosis

A detailed history and physical examination together with BMD assessment, vertebral imaging to diagnose vertebral fractures (when appropriate), and the WHO-defined 10-year estimated fracture probability test are utilized to establish an individual patient’s fracture risk (30). All postmenopausal women and men aged 50 years and above should be evaluated for osteoporosis risk in order to determine the need for BMD testing and/or vertebral imaging.

In general, the more the risk factors, larger is the risk of fracture. Osteoporosis is preventable and treatable, but because there are no warning signs prior to a fracture, many people are not being diagnosed in time to receive effective therapy during the early phase of this disease. Universal recommendations for all patients Several interventions, including an adequate intake of calcium and V-D, are fundamental aspects for any osteoporosis prevention or treatment program, including lifelong regular weight-bearing and muscle-strengthening exercises, cessation of tobacco use and excess alcohol intake, and treatment of risk factors for falling. In order to maintain serum calcium at a constant level, an external supply of adequate calcium is necessary; otherwise, low serum calcium levels promote bone resorption to bring the calcium levels to normal. Calcium requirements increase among older persons; thus, the older population is particularly susceptible to calcium deficiency. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommends a daily intake of 1000 mg/ day for men aged 50–70 years and 1200 mg of calcium for women aged over 50 years and men aged over 70 years. All calcium preparations are better absorbed when taken with food, particularly in the absence of the secretion of gastric acid. For optimal absorption, the amount of calcium should not exceed 500–600 mg per dose. Calcium carbonate is the least expensive and necessitates the use of the fewest number of tablets, but it may cause gastrointestinal (GI) complaints. Calcium citrate is more expensive, and a larger number of tablets are needed to achieve the desired dose; however, its absorption is not dependent on gastric acid, and it does not cause GI complaints. Some food products contain excess oxalate, which prevents absorption of calcium by binding with it. Intakes in excess of 1200-1500 mg/ day may increase the risk of developing kidney stones, cardiovascular diseases, and strokes. Vitamin D is necessary for calcium absorption, bone health, muscle performance, and balance. The IOM recommends a dose of 600 IU/ day until the age of 70 years in adults and 800 IU/day thereafter.

Chief dietary sources of V-D include V-D–fortified milk, juices and cereals, saltwater fish, and liver. Supplementation with V-D2 (ergocalciferol) or V-D3 (cholecalciferol) may be used. Many older patients are at a high risk for V-D deficiency, which include the following: patients with malabsorption issues (e.g., celiac disease) or other intestinal diseases (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, gastric bypass surgery); gastric acidity; pernicious anaemia; proton pump inhibitors; chronic renal or liver insufficiency; patients on medications that increase the breakdown of V-D (e.g., some anticonvulsive drugs); or glucocorticoids, which decrease calcium absorption; housebound and chronically ill patients; persons with limited sun exposure; individuals with very dark skin; and obese individuals. Serum 25 (OH) D levels should be measured in patients at the risk of V-D deficiency. V-D supplements should be recommended in amounts sufficient to bring the serum 25 (OH) D level to approximately 30 ng/mL (75 nmol/L). Many patients with osteoporosis will need more than the general recommendation of 800-1000 IU/day. The safe upper limit for V-D intake for the general adult population was increased to 4000 IU/day in 2010.

Alcohol

Excessive intake of alcohol has detrimental effects on bones, so it should be avoided. The mechanisms are multifactorial and include predisposition to falls, calcium deficiency, and chronic liver disease, which, in turn, results in predisposition toward V-D deficiency. Persons predisposed toward osteoporosis should be advised against consuming more than 7 drinks/ week, 1 drink being equivalent to 120 mL of wine, 30 mL of liquor, or 260 mL of beer. Caffeine: Patients should be advised to limit their caffeine intake to less than 1 to 2 servings (8 to 12 ounces in each serving) of caffeinated drinks per day. Some studies showed that there is a relationship between caffeine consumption and fracture risk.

Exercise

A regular weight-bearing exercise regimen (for example, walking 30-40 min per session) along with back and posture exercises for a few minutes on most days of the week should be advocated throughout life. Children and young adults who are active reach a higher peak bone mass than those who are not. Among older patients, these exercises help slow bone loss attributable to disuse, improve balance, and increase muscle strength, ultimately reducing the risk of falls. Patients should avoid forward flexion, side-bending exercises, or lifting heavy objects because pushing, pulling, lifting, and bending activities compress the spine, leading to fractures.

Conclusion

Osteoporosis is a common and silent disease until it is complicated by fractures that become common. It was estimated that 50% women and 20% of men over the age of 50 years will have an osteoporosis-related fracture in their remaining life. These fractures are responsible for lasting disability, impaired quality of life, and increased mortality, with enormous medical and heavy personnel burden on both the patient’s and nation’s economy. Osteoporosis can be diagnosed and prevented with effective treatments before fractures occur. Therefore, the prevention, detection, and treatment of osteoporosis should be a mandate of primary healthcare providers.

Healthline. (2020, September 18). How to do a full body stretching routine.

Professional sprinters sometimes spend an hour warming up for a race that lasts about 10 seconds. In fact, it’s common for many athletes to perform dynamic stretches in their warmup and static stretches in their cooldown to help keep their muscles healthy.

Even if you’re not an athlete, including stretches in your daily routine has many benefits. Not only can stretching help you avoid injuries, it may also help slow down age-related mobility loss and improve circulation. Let’s take a closer look at the numerous benefits of full-body stretching and how to build a stretching routine that targets all your major muscle groups.

What are the benefits of stretching?

Stretching regularly can have benefits for both your mental and physical health. Some of the key benefits include:

- Decreased injury risk: Regular stretching may help reduce your risk of joint and muscle injuries.

- Improved athletic performance: Focusing on dynamic stretches before exercising may improve your athletic performance by reducing joint restrictions, according to a 2018 scientific review.

- Improved circulation: A 2015 study of 16 men found that a 4-week static stretching program improved their blood vessel function.

- Increased range of motion: A 2019 study of 24 young adults found that both static and dynamic stretching can improve your range of motion.

- Less pain: A 2015 study on 88 university students found that an 8-week stretching and strengthening routine was able to significantly reduce pain caused by poor posture.

- Relaxation: Many people find that stretching with deep and slow breathing helps promote feelings of relaxation.

When to stretch

There are many ways to stretch, and some types of stretches are better at certain times. Two common types of stretches include:

- Dynamic stretches: Dynamic stretching involves actively moving a joint or muscle through its full range of motion. This helps get your muscles warmed up and ready for exercise. Examples of dynamic stretches include arm circles and leg swings.

- Static stretches: Static stretching involves stretches that you hold in place for at least 15 seconds or longer without moving. This helps your muscles loosen up, especially after exercise.

Before exercise

Warm muscles tend to perform better than cold muscles. It’s important to include stretching in your warmup routine so you can get your muscles ready for the upcoming activity.

Although it’s still a topic of debate, there’s evidence that static stretching before exercise can reduce power and strength output in athletes.

If you’re training for a power or speed-based sport, you may want to avoid static stretching in your warmup and opt for dynamic stretching instead.

After exercise

Including static stretching after your workout may help reduce muscle soreness Trusted Source caused by strenuous exercise. It’s a good idea to stretch all parts of your body, with an emphasis on the muscles you used during your workout.

After sitting and before bed

Static stretching activates your parasympathetic nervous system, according to a 2014 study of 20 young adult males.

Your parasympathetic nervous system is responsible for your body’s rest and digestive functions. This may be why many people find stretching before bed helps them relax and de-stress at the end of the day. Stretching after a period of prolonged inactivity can help increase blood flow to your muscles and reduce stiffness. This is why it feels good — and is beneficial — to stretch after waking up or after sitting for a long period of time.

How to do a full-body stretching routine

When putting together a full-body stretching routine, aim to include at least one stretch for each major muscle group in your body.

You may find that certain muscles feel particularly stiff and need extra attention. For example, people who sit a lot often have tight muscles in their neck, hips, legs, and upper back.

To target particularly stiff areas, you can:

- perform multiple stretches for that muscle group

- hold the stretch longer

- perform the stretch more than once

Calf stretch

- Muscles stretched: calves

- When to perform: after running or any time you have tight calves

- Safety tip: Stop immediately if you feel pain in your Achilles tendon, where your calf attaches to your ankle.

How to do this stretch:

- Stand with your hands against the back of a chair or on a wall.

- Stagger your feet, one in front of the other. Keep your back leg straight, your front knee slightly bent, and both feet flat on the ground.

- Keeping your back knee straight and back your foot flat on the ground, bend your front knee to lean toward the chair or wall. Do this until you feel a gentle stretch in the calf of your back leg.

- Hold the stretch for about 30 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

Leg swings

- Muscles stretched: hips, inner thigh, glutes

- When to perform: before a workout

- Safety tip: Start with smaller swings and make each swing bigger as your muscles loosen.

How to do this stretch:

- Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart.

- Balancing on your left leg, swing your right leg back and forth in front of your body, only going as far as is comfortable.

- Perform 20 reps.

- Repeat on the other side.

Hamstring stretch

- Muscles stretched: hamstring, lower back

- When to perform: after your workout, before bed, or when your hamstrings are tight

- Safety tip: If you can’t touch your toes, try resting your hands on the ground or on your leg instead.

How to do this stretch:

- Sit on a soft surface, with one leg straight out in front of you. Place your opposite foot against the inner thigh of your straight leg.

- While keeping your back straight, lean forward and reach for your toes.

- When you feel a stretch in the back of your extended leg, hold for 30 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

Standing quadriceps stretch

- Muscles stretched: quadriceps

- When to perform: after running or whenever your thighs feel tight.

- Safety tip: Aim for a gentle stretch; overstretching can cause your muscles to become tighter.

How to do this stretch:

- Stand upright and pull your right foot to your butt, holding it there with your right hand.

- Keep your knee pointing downward and your pelvis tucked under your hips throughout the stretch.

- Hold for 30 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

Glute stretch

- Muscles stretched: glutes, hips

- When to perform: after running or before bed

- Safety tip: Stop if you feel pain in your knees, hips, or anywhere else.

How to do this stretch:

- Lie on your back with your legs up and your knees bent at a 90-degree angle.

- Cross your left ankle over your right knee.

- Grab your right leg (either over or behind your knee) and pull it toward your face until you feel a stretch in your opposite hip.

- Hold for 30 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

Upper back stretch

- Muscles stretched: back, shoulders, neck

- When to perform: after prolonged sitting or whenever your back is stiff

- Safety tip: Try to stretch both sides equally. Don’t force the stretch beyond what’s comfortable.

How to do this stretch:

- Sit in a chair with your back straight, core engaged, and ankles in line with your knees.

- Twist your body to the right by pushing against the right side of the chair with your left hand.

- Hold for 30 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

Chest stretch

- Muscles stretched: chest, biceps, shoulders

- When to perform: after long periods of sitting

- Safety tip: Stop immediately if you feel discomfort in your shoulder.

How to do this stretch:

- Stand in an open doorway and place your forearms vertically on the doorframe.

- Lean forward until you feel a stretch through your chest.

- Hold the stretch for 30 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

Neck circles

- Muscles stretched: neck

- When to perform: after sitting or whenever your neck feels tight

- Safety tip: It’s normal to have one side that feels tighter than the other. Try holding the stretch longer on the side that feels tighter.

How to do this stretch:

- Drop your chin toward your chest.

- Tilt your head to the left until you feel a stretch along the right side of your neck.

- Hold for 30 to 60 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

The bottom line

Stretching regularly can:

- improve your range of motion

- reduce your risk of injury

- improve circulation

- boost athletic performance

If you’re looking to create a full-body stretching routine, try to choose at least one stretch that targets each major muscle group.

The stretches covered in this article are a good start, but there are many other stretches you can add to your routine. If you have an injury or want to know what kinds of stretches may work best for you, be sure to talk with a certified personal trainer or physical therapist.

McCann, A. (2006). Stroke survivor: A personal guide to coping and recovery. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

A physiological warning of stroke – transient ischaemic attack

The most common warning sign of stroke is the transient ischaemic attack (TIA). A TIA is often referred to as a ‘mini-stroke’, and is a short period of disturbance of body function, lasting for less than 24 hours, resulting from a temporary reduction in blood supply to part of the brain. Depending on the area of the brain affected by a TIA, the sufferer can have a temporary loss of limb sensation or strength, a loss of vision, or even a loss of consciousness. A TIA commonly lasts between two and 15 minutes, and having been rapid in its onset leaves no persistent neurological deficit. However, TIAs must always be taken seriously no matter how quickly they pass, as they are a clear warning that a life-threatening stroke may occur soon.

TIAs should always be investigated, the cause should be found and, if possible, treated. Without treatment, about one in four people who have had a TIA will have a stroke within the next few years. It is therefore quite clear that each and every TIA should be taken seriously, by both the individual concerned and those members of the medical profession he or she presents to. It is not too late to seek medical attention or advice even when the symptoms have gone away.

The important emphasis in terms of identifying the cause of a stroke is that, if at all possible, it should be done before the stroke happens, in a proactive, preventative way, and not afterwards in a reactive, rehabilitative way. However, until the general population take some responsibility for themselves, scientists are still trying to develop and improve risk-score methods to predict, and aim to prevent, a stroke. The Oxford Stroke Prevention Research Unit has identified four factors that could predict the future risk of a stroke if an individual suffers and reports a TIA. These are:

- The Age of the individual

- The Blood pressure of the individual

- The Clinical features (i.e., the symptoms) the individual presents

- The Duration of the TIA.

Simply speaking, by translating these facts to create an ABCD score, the high-risk individuals, who may need emergency treatment, can be identified. The majority of TIAs are the result of arterial or cardiac thromboses, but they may equally be associated with high blood pressure, smoking, obesity, high cholesterol levels, or a combination of all of these.

he onset of stroke. The primary identifying feature of stroke is its acute and sudden onset. In other words, the symptoms of stroke happen immediately. In rare cases, these symptoms of a stroke can be difficult to attribute to a stroke with any certainty, even for doctors. However, this is not usually the case, and a failure to identify the symptoms of a stroke in another is really the result of poor education or ignorance caused by complacency. In a 1996 Gallup survey conducted for the National Stroke Association, 17 per cent of adults over age 50 were unable to name a single stroke symptom. Unfortunately, such a lack of awareness can spell disaster. The stroke victim may suffer significant brain damage when people nearby fail to recognise the symptoms of a stroke.

As I have discussed, each part of the brain has more than one specific function and each part of the brain can be subject to a stroke. As a result, the general and most common symptoms of stroke include:

- numbness or weakness in the face, arms or legs (especially on one side of the body)

- confusion, difficulty speaking or understanding speech

- vision disturbances in one or both eyes

- dizziness

- some trouble walking

- a loss of balance or co-ordination

- a severe headache with no known cause.

While the symptoms may be inconsistent, depending on the area of the brain affected by the interruption in normal blood flow, there can be no doubt of the following – the longer blood flow is cut off to the brain, the greater the potential for permanent damage to the brain. Within a few minutes of the onset of a stroke, the area of the brain affected is damaged, some of it beyond repair.

Any observer can recognise a possible stroke by asking the following three simple questions of the person suffering:

- Can you raise your arms and keep them up?

- Can you smile?

- Can you repeat a simple sentence?

If the answer to one or more of these questions is ‘no’, then immediate medical attention should be sought. If the individual in distress has in fact had a stroke, the full and lasting effects, as I have said, will be dependent upon the area of the brain affected and the speed with which medical attention is given.

Why stroke occurs

I have mentioned previously that a stroke occurs when a blood clot blocks a blood vessel or artery, or when a blood vessel breaks, interrupting blood flow to an area of the brain. It most often occurs when the carotid arteries become blocked, and the brain does not get enough oxygen. The physical damage depends upon which blood vessel is damaged and whether the damage was due to blockage or haemorrhage.

Stroke caused by a blockage or clot – ischemia

In everyday life, blood clotting is most beneficial. When an individual bleeds from a wound, blood clots work to slow and eventually stop the bleeding. In the case of a stroke, however, blood clots are dangerous because they can block arteries and cut off blood flow. Ischaemic strokes can happen as the result of unhealthy blood vessels, which are clogged with a build-up of fatty deposits and cholesterol. This condition is known as ‘atherosclerosis’. The body regards atherosclerosis as multiple, tiny and repeated injuries to the blood vessel wall. It then reacts to these injuries just as if it was bleeding from a wound, and it responds by forming clots. Atherosclerosis is often associated with stroke and the supply of blood to the brain, and is the progressive narrowing and hardening of arteries over time. It is known to occur with ageing, but other factors include high cholesterol, high blood pressure, smoking, diabetes and a family history of atherosclerotic disease. Other causes of ischaemic stroke include use of street drugs, traumatic injury to the blood vessels of the neck, or disorders of blood clotting.

Approximately 80 per cent of all strokes are ischaemic. Due to the contributory factors of ischaemic stroke mentioned above, many people who suffer them are older (60 or more years old), and the risk of ischaemic stroke increases with age. As I clarified earlier, an ischaemic stroke can occur in two ways, and will then often be classified as an ‘embolic’ or a ‘thrombotic’ stroke.

Embolic stroke

With an embolic stroke, a blood clot forms somewhere in the body and then moves. This kind of blockage causing a stroke is called a ‘cerebral embolism’. While it may form in the arteries of the chest and neck, a part may break off before travelling through the bloodstream to the brain. Alternatively, it may possibly form in the heart, but again a part may break off and travel to the brain.

Once in the brain, the clot eventually travels through the system until it reaches a blood vessel small enough to block its passage. When it can travel no further, the clot lodges there blocking the blood vessel and causing a stroke.

Thrombotic stroke

In the case of a thrombotic stroke, blood flow is impaired because of a blockage that has built up in one or more of the arteries supplying blood to the brain, most often in the large arteries, such as the carotid artery or middle cerebral artery. A significant number of strokes are caused by blockages and narrowing of the carotid arteries and carotid artery disease increases the risk for stroke in three ways:

- through fatty deposits (cholesterol or plaque) building up and severely narrowing the carotid arteries

- by a blood clot becoming stuck in a carotid artery, which has already been narrowed by plaque

- by plaque breaking off from the carotid arteries and in so doing blocking one of the smaller arteries in the brain (cerebral artery).

Generally speaking, if a carotid artery is blocked then a cerebral stroke will result. If a vertebral artery is blocked, then a cerebellar or brainstem stroke will result. The process leading to this blockage is what is known as thrombosis, and there are two types of thrombosis which can cause a stroke – large vessel thrombosis and small vessel disease. Large vessel thrombosis is the most common, and probably the most understood type of thrombotic stroke. Most large vessel thrombosis is caused by a combination of long-term atherosclerosis, followed by a rapid blood clot formation. It is common that thrombotic stroke patients are also likely to have coronary artery disease, and actually a heart attack is a frequent cause of death in patients who have suffered this type of stroke.

Small vessel disease (also called lacunar infarction) occurs when the blood flow is blocked to a very small, but often a deep, penetrating, arterial vessel. Very little is known about the causes of small vessel disease, but it seems to be very closely linked to hypertension.

Stroke caused by bleeding – haemorrhage

In the case of a haemorrhagic stroke, which accounts for the remaining 20 per cent of strokes after ischaemic strokes, it is, as I have already said, the breakage of a blood vessel in the brain that leads to bleeding. The bleeding then irritates the brain tissue and causes swelling (known as cerebral oedema). The surrounding tissues of the brain resist the bleeding, which can be contained by forming a mass (haematoma). Both swelling and haematoma will compress and displace normal brain tissue causing damage. Haemorrhages can be caused by a number of disorders, which affect the blood vessels, including long-standing hypertension (high blood pressure), high cholesterol and cerebral aneurysms (see Glossary). A cerebral aneurysm, usually present at birth, can develop over a number of years and may not cause a detectable problem until it breaks. As I clarified earlier, there are two categories of stroke caused by haemorrhage – subarachnoid and intracerebral.

In a subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH), an aneurysm bursts in a large artery on or near the thin, delicate membrane surrounding the brain. Blood then spills into the area around the brain causing a stroke. This tends to be managed very differently from other strokes. Bleeding may recur within weeks and there is a far greater chance that surgery will be needed to repair the artery. In the case of an intracerebral haemorrhage, bleeding occurs from vessels within the brain itself. As I stated earlier, hypertension is the primary cause of this type of haemorrhage.

After a Stroke - The effects of stroke

Trying to summarise all the possible effects of a stroke under one heading is close to an impossible task. There are simply too many individual factors, which vary from individual to individual, to take into account. In my opinion, the important issues regarding the effects of a stroke become really evident with the answers to these questions:

- Why…has a stroke occurred?

- How…could an individual be affected?

- Who…is available to support recovery?

- What…can be implemented to aid with recovery, or improve the quality of life for all those affected?

The Why? has been discussed above. The How? is discussed below. The Who? and What? are both considered in later chapters.

The specific abilities that will be lost or affected by stroke depend on:

- the extent of the brain damage

- where in the brain the stroke occurred.

In order to begin to appreciate how an individual can be affected having survived a stroke, I think that our knowledge of how the brain works should be applied. Therefore, I have decided to include an overview of the most common effects first by hemisphere, and then by individual sections of the brain.

Hemisphere strokes

Possible effects of a right-sided stroke:

- Movement and mobility: left hemiplegia (see Glossary), and some spatial and perceptual problems