In this section you will learn to:

- Consider theories and models of grief and bereavement to enhance your understanding of grief and loss reactions and processes.

- Recognise and take into account individual, social, cultural, and spiritual factors that may influence the grieving process.

Grief theories provide a conceptual base for understanding grief and loss as a process involving many common characteristics and phases. Although you are not required to know the models and theories associated with the field of grief and loss in great depth, a general understanding of these will help you understand and anticipate the process that people may go through. This will help you to identify and normalise reactions to loss, and to identify where further help may be needed.

Stage and Phase-Based Models

Many theories of grief, and particularly bereavement, suggest that people go through stages or phases in their grieving process. Whilst the stages and phases are slightly different in each theoretical model, they are similar in proposing that people need to move through these stages or phases in order to reach some kind of recovery. These models are prone to create problems when an individual’s experience does not match with the suggested stages or phases of a given theory, and there is limited evidence that the models describe what most, let alone all, bereaved people will go through.

Attachment Theory and Grief

Attachment theory explores the nature of the connection or attachment between humans, particularly between primary caregivers and infants, and the consequences of separation. Bowlby hypothesised that the grief process reflects the disruption of attachment bonds – resulting in similar distress behaviours displayed by infants when they are separated from their primary caregiver such as crying, clinging, and anger designed to regain the connection (Pomeroy & Garcia, 2009). Bowlby’s observations of mourning were then expanded by others into phases of grieving: numbness; yearning and searching; disorganisation and despair; and reorganisation (Harris & Winokuer, 2016). The idea that attachment has a significant influence on grief has also been adopted by many others (e.g., Worden, 2009), but there is a lack of empirical evidence to support the attachment-based stage model of grief (Machin, 2014). Some research has also questioned the tenet that attachment style predicts adult adjustment more broadly (Lewis, Feiring, & Rosenthal, 2000).

Task-Oriented Models of Grief

Some more recent models of grief suggest that rather than fixed stages, the grieving process presents people who experience a loss with a series of tasks associated with ‘processing’ or ‘progressing through’ grief (McLeod & McLeod, 2011). Those who promote task models claim a distinction between them and stage models: namely that stage models describe grieving while task models describe processes in which bereaved people can actively engage. However, they share many of the characteristics (and criticisms) of stage models.

Rando’s ‘Six Rs’

Rando’s model of bereavement, also known as the ‘six Rs’, proposes that bereaved people’s processing of grief involves six tasks: recognising the loss; reacting to the separation; recollecting and re-experiencing the deceased and the relationship; relinquishing old attachments to the deceased and assumptive world; readjusting with adaptive movement into the new world; and reinvesting (McCoyd & Walter, 2016). As with stage theories, there are significant criticisms of task theories, including this one. These criticisms are very similar to those of stage models and include: that Rando claims her processes are universal (i.e., experienced by everyone who experiences loss and grief, regardless of individual and cultural circumstances); that Rando claims that bereaved people must move through these processes in order to heal; and that task model, in general, suffer from a lack of empirical support (i.e., they are not supported by research) (McCoyd & Walter, 2016; Ober, Granello, & Wheaton, 2012).

Worden’s Model

Worden (2009) identified four key tasks he believes to be required for a healthy grieving process:

Task 1: Acknowledging the reality of the loss. The mourner needs to cease denying that the death has occurred and come to believe that the loved person is truly dead and cannot return to life. The mourner needs to examine and assess the true nature of the loss and neither minimise nor exaggerate it.

Task 2: Processing the pain of grief. Sadness, despondency, anger, fatigue and distress are all normal responses to the death of a loved person; people should be encouraged to experience these feelings in appropriate and supported ways so that they do not carry them throughout their lives.

Task 3: Adjusting to a world in which the deceased person is missing. A full awareness of the loss of all the roles performed by the deceased in the life of the mourner may take some time to realise. Challenges to growth are presented to the mourner as he or she assumes new roles and begins to redefine himself or herself, often by learning new coping skills or by refocusing attention on other people and activities.

Task 4: Finding an enduring connection with the deceased in the midst of embarking on a new life. It is important for the bereaved individual to find an appropriate place for the deceased person to occupy in a spiritual or nontangible sense. This task involves creating and sustaining an appropriate relationship with the deceased based on an ongoing emotional connection and memory, so that person will never be wholly lost to them.

(Adapted from Harris & Winokuer, 2016, p. 34)

A strength of Worden’s approach is that it is an active model which encourages responding to each client’s individual presentation and can assist clients in identifying their own needs and goals, which is critical to providing support in the context of grief (Harris & Winokuer, 2016). Despite the tasks being numbered, Worden (2009) has stated that they should not be viewed as fixed or prescriptive, but that “tasks can be revisited and worked through again and again over time. Various tasks can also be worked on at the same time” (Worden, 2009, p. 53).

Nonetheless, it is problematic and potentially harmful to insist that a task must be undertaken; you may have noticed in the extract above that the tasks specify things that Worden believes ‘need’ to be done. It is also perfectly understandable that people would assume that a numbered series of tasks, such as Worden’s, indicates that the tasks are discrete and sequential (with all the problems this entails). It is also problematic to assume that aspects of grieving are universal and, as mentioned in regard to Rando’s model, there is a general lack of research evidence to suggest that task models are accurate in their ideas about grief and how it should be addressed.

Contemporary Approaches to Loss and Grief

More recent approaches to loss and grief focus more on adjustment to and integrating loss, rather than on ‘recovery’ or ‘resolution’. There is the acknowledgement that, while grief may diminish over time, it may continue to have a presence in a person’s life, with the potential for reactivation at certain times (e.g. anniversaries, milestones) (Winokuer & Harris, 2012). For example, a girl whose mother dies when she is 8 years old may experience a resurgence of grief later in her life as she experiences her mother’s absence at significant life events such as marriage and having children herself. There is also an increasing acknowledgement that patterns of grieving vary widely according to individual, social, and cultural factors.

The Dual Process Model

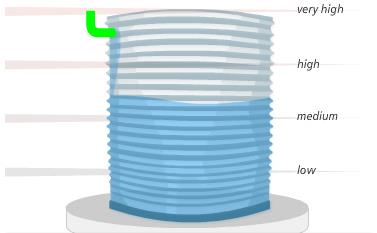

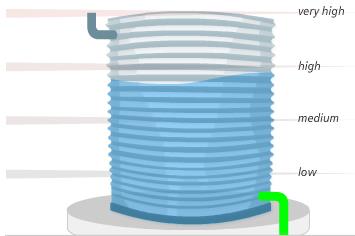

Developed from a cognitive stress perspective, the dual process model of grief describes the grief experience as a process of oscillation (i.e. movement) between two modes of functioning: loss orientation and restoration orientation.

Examination of the phenomena of bereavement suggests that people undertake in varying proportions (according to individual and cultural variations), what we call loss- and restoration-orientated coping. These refer to two categories of stressor, each of which requires coping efforts during bereavement. It is evident that coping does not occupy all of a bereaved person’s time: Coping is embedded in everyday life experience, which involves taking time off from grieving, as when watching an engrossing TV program, reading, talking with friends about some other topic, or sleeping.”

(Stroebe & Schut, 1999, p. 1999)

In the loss orientation, people may be immersed in the pain of separation, missing what has been lost, and coming to terms with the loss. At other times, in the restoration orientation mode, the person engages in day-to-day activities, general life tasks, the things that need to be done in the aftermath of the loss, problem-solving, making appropriate adjustments, and focusing on other aspects of life (Hall, 2011). This process is depicted by Machin (2009, p. 44):

The adaptive, regulatory function of oscillation in the model is important to note. The ‘break’ from the distressing, sometimes overwhelming nature of loss orientation is important for mental and physical health, and necessary for “optimal adjustment over time” (Stroebe & Schut, 1999, p. 216). Worden (2009) uses the notion of ‘dosing’ to describe how bereaved people may expose themselves to the amount of pain they are able to cope with before switching to restoration-orientation coping strategies.

The model suggests that the focus of coping with grief may “differ from one moment to another, from one individual to another, and from one cultural group to another” (Hall, 2001). The dual process model uses these differences in coping to account for the diversity in the grief experience across individuals.

Continuing Bonds

While classical grief theory based on psychodynamic principles suggested that ‘recovery’ from bereavement involved disengaging from or ‘letting go’ of a deceased individual, more recent theories and practices focus on maintaining a sense of continuity. This may be through memory and a “revised inner representation of the deceased (or person or thing which has been lost)” (Machin, 2009, p. 5). Pomeroy and Garcia provide an example of one way in which a widower continued the bond with his dead wife:

A 75-year-old gentleman loses his wife after 50 years of marriage and remarries 2 years later to a woman who was friends with his wife. He often stated that his new wife made him feel more connected to his former wife because they were friends and shared a common history.

(Pomeroy & Garcia, 2009, p. 6)

Many non-Western cultures show the significance of continued bonds through religious beliefs and rituals. For example, in Japanese culture, the maintenance of ties with the deceased is accepted and sustained by religious rituals.

The ancestor remains accessible, the mourner can talk to the ancestor, he can offer goodies such as food or even cigars. Altogether, the ancestor ‘remains with the bereaved’ (p. 181). This cultivation of continued contact with the deceased is facilitated by the presence in nearly all homes of an altar dedicated to the family ancestors. Offering food at the altar of a loved one would classified as pathological by most Westerners, who fear that the bereaved was fixated in the grief process and had failed to relinquish the tie to the deceased. However, in the Japanese, such practices are fully normal.

(Yamamoto, 1970, cited in Stroebe et al., 1996, p. 35)

Meaning Making

Significant loss, and particularly bereavement, can challenge our assumptions and beliefs about the world. Through loss, we may learn that not everyone is trustworthy – that some people harm others; that the world is not always a safe or predictable place; and that we have little ability to prevent many ‘bad things’ from happening to us (Winokuer & Harris, 2012). The reconstruction of one’s assumptive world, therefore, can be a central task for those who experience bereavement and other significant losses. It involves ‘relearning’ aspects of the self and the world (Attig, 1996). Such adjustments can include attempts to integrate the loss into the griever’s ‘personal narrative’, where the loss fits into “a meaningful plot structure” (Neimeyer, Prigerson & Davis, 2002, p.239). This, in turn, can involve the use of narratives and life stories or other activities such as those described below:

Bereavement specialists now view adaptive mourning as best facilitated through transforming losses to continuing bonds in spiritual connections, memories, deeds, and stories that are passed on across the generations (Neimeyer, 2001; Walsh & McGoldrick, 2004). Coming to terms with traumatic loss involves making meaning of the trauma experience, putting it in perspective, and weaving the experience of loss and recovery into the fabric of individual and collective identity and life passage.

(Walsh, 2007, p. 210)

Meaning-making can involve talking or not talking – it doesn’t have to be about story-telling, although that can be how it appears. People might make meaning out of creating artworks, committing to a particular practice or enacting a particular value, or working to support a particular cause, to take just a few examples of the many ways that meaning-making can be done.

Self-Reflection

Think about your own experience of the grieving process or the experience of a close friend or relative. Can you recognise some of the features of the grieving process described in the models above? Does a particular model seem to fit your experiences particularly well, or which help you understand your response to the loss? Are there models that you find particularly unhelpful in relation to your own experience? How might individual differences and variations in circumstance impact how useful a particular model is?

As you can see, approaches to grief have started to move away from stage, phase, and task-based models to focus on helping people integrate their memories and the importance of what has been lost into their present and future lives.

In a classic paper, Wortman and Silver (1989) reviewed the research literature on loss and grief, and came to the conclusion that there are no fixed and predictable patterns of coping with loss: there are major differences between people in terms of how severely they are affected, how long the grieving process takes, whether they go through stages of anger and depression, and so on. Wortman and Silver (1989) urge caution on the part of those working in the field of bereavement against allowing themselves to be caught up in prevailing ‘myths’ around the grieving process. The implication is that while theory and research on bereavement may be valuable as a means of sensitising practitioners to possible patterns of coping with loss, in the end the touchstone always needs to be the reality being experienced by the client themselves.

(McLeod & McLeod, 2011, p. 288)

There are various factors that help account for this diversity in how people grieve, from individual differences to the type of loss to the family and cultural environment the person is in. Having an appreciation and understanding of the impact and influence of these factors will help you to respond to specific client needs based on their individual situation.

Worden (2009) identifies seven factors that may be particularly important in gaining an understanding of a particular person’s grief experience after death. He refers to these as the ‘mediators of mourning’. Let’s explore each of these in turn.

1. Relationship with The Deceased

Relationships, including their meanings and consequences on an individual’s perception of themselves, strongly influence the nature of the grief response (Machin, 2009). How the person was related or connected to the deceased person will therefore influence how they might grieve. Generally, the closer the person was to the deceased, the more intense the bereavement. For example, the loss of a grandparent who lived in a different country will be mourned differently from the loss of a parent or sibling with whom a person is very close. However, it is important to acknowledge that even if the relationship bond is similar (i.e., children losing a parent), each person will experience this loss differently (Worden, 2009).

2. Nature of the Attachment

As you have already learned, some theorists have likened grief to the distress experienced by individuals who have been separated from their attachment object (i.e., person). Worden (2009) considered attachment to be critical in grief, and suggests that:

- The strength of attachment (he suggests that the grief response often increases in intensity in proportion to the intensity of the relationship with the deceased).

- The security of the attachment.

- The ambivalence in the relationship and/or conflict with the deceased. These factors may result in feelings of guilt or unresolved anger.

- Dependent relationships: Worden suggests that relationships that were ‘enmeshed’ and characterised by high dependency can affect an individual’s ability to adjust to a life without the deceased, particularly where that person carried out many of the day-to-day tasks such as paying bills, driving, and organising social activities.

3. How the Person Died

Factors such as physical proximity, levels of violence or trauma, suddenness, multiple losses, whether the death was preventable, or if there is any social stigma associated with it, can all pose significant challenges for the bereaved (Worden, 2009). Walsh explores some particular aspects of death that may create particular challenges or distress in its aftermath:

Situations of traumatic death and loss

The meaning and impact of traumatic deaths are influenced by a number of variables in the loss situation that require careful assessment and attention.

Violent death. A violent death is devastating for loved ones and for those who witnessed it or narrowly survived. Preoccupation with causal accusations, guilt, or wishes for retaliation is common. A senseless tragedy, loss of innocent lives, and deliberate acts of violence are especially hard to bear.

Untimely death. Untimely losses are the hardest to bear. The death of a child or young spouse seems unjust and robs future hopes and dreams. The loss of parents with young children requires reorganization of the family system.

Sudden death. Sudden losses shatter a sense of normalcy and predictability. Shock, intense emotions, disorganization, and confusion are common in the immediate aftermath. Loved ones, unable even to say their goodbyes, may need help with painful regrets.

Prolonged suffering. Prolonged physical or emotional suffering before death (e.g., with assault, torture, or lack of medical care) increases family agony, as well as anger or remorse.

Ambiguous loss. Unclarity about the fate of a missing loved one can immobilize families who may be torn apart, hoping for the best yet fearing the worst (Boss, 1999). Mourning may be blocked until remains or personal effects are recovered. Families may need help in pressing for information and in resuming lives in the face of lingering uncertainty.

Unacknowledged, stigmatized losses. Mourning is complicated when losses or their causes are disenfranchised (Doka, 2002), hidden because of social stigma (e.g., HIV/AIDS) or collaboration with the enemy. Secrecy, misinformation, and estrangement impede family and social support.

Pile-up effects. Families can be overwhelmed by the emotional, relational, and functional impact of multiple deaths, prolonged or recurrent trauma, and other losses (homes, jobs, communities) and disruptive transitions (separations, migration).

Past traumatic experience. Past trauma or losses, reactivated in life-threatening or loss situations, intensify the impact and complicate recovery.

(Walsh, 2007, p. 209)

There is also evidence that deaths resulting from suicide pose significant additional challenges for those bereaved by them (Worden, 2009).

4. Historical Antecedents

It is important to remember client's come to with varied histories and experiences, all of which influence their current situation. This is no different when it comes to grief and loss. A person’s experience of loss may be shaped by the previous losses they have experienced, how they have grieved these losses, and their mental health history, for example (Worden, 2009). As you should recall from section one, cumulative grief results when a person suffers several losses over a period of time. This can mean that adjusting to additional losses may be more challenging. Cumulative losses can also result in an accumulation of stress, which can increase vulnerability to further mental health issues.

Some types of loss and trauma can also have impacts across generations. This is particularly relevant for Indigenous communities who have experienced historical loss and trauma through colonisation and displacement. Many Indigenous people have suffered the loss of their lands, cultures, languages, and families – as well as experiencing other traumas – which have impacted them personally and as a community (Calvary Health Care).

5. Personality Variables

We started exploring the highly variable and diverse nature of grief responses in the previous section of this Study Guide. While a large part of this variation can be explained by individual circumstances in combination with cultural and social context (which you will be learning about shortly), psychological variables such as personality, coping methods, attachment style, beliefs, and values also influence the grief experience.

A person’s personality and habits may influence their grief responses. For example, an introverted person who is not typically emotionally demonstrative is unlikely to suddenly become highly expressive after experiencing a significant loss (Winokuer & Harris, 2012). Their learned and habitual ways of coping and other personal factors can also have an influence. This is one of the reasons why theories of grief that propose particular experiences and processes as part of the grief response are so problematic: they do not take into account the ways that people vary in their experiences, expressions, and ways of coping.

Coping Styles

Coping refers to our efforts to adjust to the demands of a situation, and includes both behaviour and cognition (i.e., ways of thinking) (Humphrey & Zimpfer, 2008). Significant loss events such as bereavement represent situations that place demands on people, and to which they must adjust, so coping strategies are an important consideration in situations of loss and grief. Bereaved people’s typical ways of coping with stressful situations are likely to have an influence on how they respond to loss (Winokuer & Harris, 2012).

According to Worden (2009), coping strategies include:

- Problem-solving coping. An instrumental coping mechanism that aims to locate the source of the problem and determine solutions. People vary in their ability to problem-solve (and, of course, some situations are more or less amenable to problem-solving).

- Active emotional coping. This type of coping involves strategies such as humour, reframing, the ability to identify something positive in a situation, expression of emotion, and the ability to accept support.

- Avoidant emotional coping. These strategies include blame (of self or others) and other strategies such as distraction, denial, and social withdrawal; as you might imagine, this type of coping can become unhelpful if maintained for long periods of time. Using substances such as drugs, alcohol, or food to manage intense distress also falls into this category.

The example below shows a person with a problem-solving coping style adopting an avoidant emotional coping style when faced with the loss of his wife.

Case Study

Roger, a retiree with mobility limitations, had built a comfortable life for his family. When his wife was diagnosed with cancer, Roger became her primary caregiver, using his organisation skills to manage her treatment and comfort. Six months after her passing, Roger began to feel deep sadness and withdrawal. To avoid his grief, he isolated himself from friends and family, focusing entirely on activities and routines that distracted him. This coping strategy left him struggling to process his emotions and adjust to life without his wife.

Self-Reflection

Take a few moments to reflect upon each of the above-mentioned coping strategies. Why do you think that avoidant emotional coping would be less effective than active emotional coping or problem-solving coping?

Worden (2009) suggests that avoidant emotional coping may be the least effective coping strategy in the context of grief and loss. However, what appears to be avoidant coping can be useful at times, at least temporarily, and in some cases is not actually avoidant at all. For example, Worden also discusses the case of a bereaved man who spent significant amounts of time alone; while others were worried that this meant he was withdrawing and not ‘dealing’ with the loss, this was actually a healthy and helpful strategy for him. He was “doing his grieving … in his own way” (p. 102).

The Stress-Vulnerability Model

The stress-vulnerability model theorises that the effects of challenging events are determined by the interaction between a person’s vulnerability (the things about their genetic make-up and prior experience that mean they are more or less vulnerable to the effects of stressors); the stressors that they are exposed to; and their resources, including protective factors against the effects of stress, such as supports and coping strategies. According to the model, this interaction determines whether a breakdown of normal functioning and various risks (such as mental health risks) may occur. This model can be explored using the ‘water tank metaphor’:

Water tank metaphor

The water tank represents our genetic makeup, which is predetermined. Some people are born with bigger tanks than others and they therefore have the capacity to hold more water and greater influxes before overflowing.

The inflow pipe represents the external stressors (risk factors) that are often beyond our control. For example, rain often falls heavily and gutters fill quickly during a storm. This is equivalent to being overwhelmed by stressors – lots of stress all at once. At other times rain is minimal – not much stress. At other times rain may be regular and predictable – chronic but manageable stress.

The outflow pipe represents personal (protective) factors such as habits and learnt coping strategies, or external protective factors like social support and employment. People with good coping strategies or strong external supports can control their outflow effectively to manage the water level in the tank, even when the inflow is rapid and unpredictable. Others, particularly those with smaller tanks, might not be able to control their outflow and water levels will rise and cause overflow.

(MHPOD, n.d.)

Grief and loss present significant stressors and, interacting with the vulnerability of the person and the resources available to them (helpful coping strategies, social supports, financial resources, etc.), may lead to well-being issues. The stress-vulnerability model can be used to help understand the range of factors that may impact an individual, consider the multiple stressors they face, and identify what strategies may be helpful (including specialist referrals).

Case Study

Mary a support worker, supports two clients who recently lost their husbands in workplace accidents.

Aishah, 68, lives with a physical disability and limited mobility. She moved from Malaysia two years ago with her husband, who was her main support and caregiver. Now, with no family nearby and limited local connections beyond her cultural community, she faces both physical and emotional challenges, alongside a family history of depression.

Layla, 74, has mild cognitive impairment but remains active in her long-time community. She has strong family and friendship networks and regularly attends a seniors’ exercise group. This loss marks her first major bereavement experience, though she’s never experienced mental health issues.

Self-Reflection

These two clients may cope very differently with their husbands’ deaths. How might their different circumstances influence the impacts their losses have on them and the resources available to them?

Now draw your own ‘water tank’ and fill in your current stressors and protective factors such as employment and social support. What helps you prevent overflow? What could you do to enhance your protective factors (that is, to make your outflow pipe bigger)?

As you can see, when considering grief experiences, it is important to take into account the various stressors and protective factors that apply to clients. Interventions may then be suggested to reduce some of the stressors and enhance coping and protective factors. Social support is a key protective factor which we will be discussing in more depth in the next section of this Study Guide.

Grieving Styles

Although there are many commonalities in the grief experience, people also grieve in very different ways. Doka and Martin describe three main patterns of grieving or ‘grieving styles’, which Winokuer and Harris (2012) place on a continuum as depicted below:

| Intuitive grievers | Blended grievers | Instrumental grievers |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

People are often expected to grieve differently according to their gender, with women associated with intuitive grieving and men with instrumental grieving styles. Winokuer and Harris (2012) point out that “if people do not express grief in a way that is expected by others, their experience may be labelled ‘problematic’ or even ‘pathological’” (p. 88). It is important to identify and respect an individual’s unique style of grieving and develop interventions that meet that person’s particular need, putting aside their own assumptions about how people or particular groups of people ‘should’ or ‘usually’ grieve.

Attachment Style

You should recall the concepts of secure and insecure attachment styles from earlier in your studies. Parkes investigated the association between attachment style and bereavement outcomes and believed that individuals who had experienced secure attachment with their parents as children experienced less distress as a result of bereavement than those who had experienced insecure relationships, while those who learned to avoid attachments had difficulty expressing their feelings during bereavement (Worden, 2009). According to this model, people with secure attachment styles tend to be able to process the pain of separation and move on to develop healthy continuing bonds with the deceased loved one. Although these individuals do experience separation distress and consequent searching and pining behaviours, they are not overwhelmed by the loss. Conversely, insecure attachment styles (particularly anxious/preoccupied and anxious/ambivalent styles) are associated with difficulties in adjusting to the loss of an attachment figure, resulting in some cases in the development of complex grief (Worden, 2009).

Spirituality

As we have already discussed, spiritual practices and religious rituals are an important part of how many people make sense of and respond to loss. Spiritual questioning and quests for meaning are common components of bereavement reactions. When clients are experiencing a spiritual crisis or challenge as a result of loss, they may find it more difficult to cope with the loss and grief they are experiencing (Worden, 2009). On the other hand, clients may also draw on mental resources from their spiritual perspective or belief system to help them cope with the loss. In general, having a professional responsibility to respect and help clients work through things within the context of the client’s own spiritual framework (or lack thereof).

6. Social Mediators

So far, we have explored the influence of relationship factors, the circumstances surrounding the loss, and individual characteristics that influence the grieving process. However, people exist within a sociocultural context. As such, understanding the cultural and social factors at play is crucial in support people who are grieving.

Cultural Influences

We all belong to various cultural and social groups which are made up of smaller subcultures. These cultural groups play a large part in both what we consider to be a loss and how we grieve them. These provide us with particular rituals and behavioural guidelines for some losses, while often failing to recognise others. Every culture has norms, values, and beliefs that are considered acceptable within it, but what has considered an acceptable reaction or emotional response to death varies widely between different cultures. For example, some cultures frown upon public displays of emotion, especially negative emotions such as sadness and anger, and behaviours such as crying and sobbing. Others consider public displays of grief important and necessary. In some countries where funerals are loud and expressive affairs, while in others are quieter. And, as we have already discussed, people who grieve in ways that are not expected or considered ‘normal’ or acceptable within a given culture may experience judgement, social avoidance, or worry that they are not behaving properly.

After our previous discussions, it won’t surprise you to learn that culture can have a significant effect on the recognition of and reactions to loss, affecting:

- What a community considers to be a loss

- What life events, circumstances and relationships exist that may introduce loss into people’s lives?

- Explanations as to the cause of the loss and beliefs as to the reasons for the loss.

- How intensely the loss has a right to be grieved.

- How does the loss compare to other losses and others who experience loss?

- Who is allowed to feel distressed about the loss?

- Who is affected?

- Those who have the power to affect the loss or the grieving of it.

- The structure of the social network around the griever.

- Beliefs about how such losses can be avoided or prevented.

- The practices by which the loss will be recognised within the cultural group and the expected reactions to such practices.

- The time span offered for grieving.

- The acceptable emotions and forms of emotional expression associated with the loss.

- The meaning of the loss in the life of the group.

- The manner and interpretation of the loss into the future.

(Murray, 2016, p. 82-83)

Support workers need to consider factors such as family background, cultural practices, socio-economic status, gender, spirituality, and other cultural influences when supporting someone experiencing grief. Without cultural awareness, misunderstandings can arise, leading to misinterpretation or “labelling” of grief responses. Klass (2003) offers examples, like an Egyptian mother mourning for years or a Balinese man laughing during grief, which may be misunderstood without cultural context.

It’s essential not to assume based solely on cultural identity. For example, an Aboriginal client may draw more on their Christian faith than traditional beliefs. Understanding diverse groups and individual perspectives supports effective care.

So while it is important to understand the common cultural practices that may influence a person’s grief experience, it is important to also take into account individual differences, and avoid assumptions and stereotyping. Building your understanding of diverse groups and cultures is important and helpful, but understanding also comes from exploring the individual’s own experience:

[T]aking a deeply respectful stance of ‘not knowing’ but ‘wanting to know’. Learning how to ask people what they may need within their culture, and learning how they understand and experience the loss, are keys to dealing effectively with cultural differences.

(Murray, 2016, p. 83)

Self-Reflection

Think about the way that losses are talked about in your own family, friendship groups, and the broader community. What mourning rituals are carried out? How are funerals conducted? Are there any other practices associated with loss? What are the expectations for emotional expression or other behaviours? What losses are well recognised, and which are not?

Social Expectations

The expectations on people, from their families, friendship and peer groups, ethnic and faith communities, and broader societies also impact on the experience and expression of loss and grief. Pomeroy and Garcia discuss some of the ways that social expectations within Western culture can impact experiences of bereavement:

Due to the superficial coverage of these issues and the lack of accurate information that is disseminated about death and bereavement, many bereaved individuals find themselves feeling inadequate in how they are managing the death. Statements such as, “I don’t know why I’m having such a hard time” and “I know I should be over it by now” are indicators that societal expectations may be playing a role in the mourner’s attempts to cope with the loss. Although there are differences among cultures, some of the dominant society’s expectations suggest the following:

- One should “get over the loss and move on with life” as quickly as possible.

- A person should not talk about his/her grief in social situations.

- Grief is depressing and thus, should be avoided.

- Something is ‘wrong’ with a person who cannot mask his/her emotional response to loss.

- Distractions from the grief experience are helpful.

- There is a prescribed script of emotions that everyone should follow when experiencing grief.

- Grief should be a time-limited experience with a definite endpoint.”

(Pomeroy & Garcia, 2009, p. 12)

Such social rules can cause a great deal of difficulty for people who do not grieve in the socially expected or sanctioned way. Rather than risk isolation or rejection at this particularly vulnerable time, grieving individuals may try to conform to expectations by putting a ‘public façade’ which does not reflect their inner experience.

Case Study

Liam, a 63-year-old with limited mobility, recently lost his wife, Helen, after her three-year struggle with cancer. Married for 40 years, they shared a close partnership, and Helen had helped him manage many tasks affected by his disability. Now, Liam faces not only his grief but also societal expectations that may influence how he expresses it—especially as an older man who’s traditionally been seen as independent. Friends and family expect him to adjust quickly, but without Helen, his social support feels diminished.

In her absence, Liam also finds it challenging to adjust to shifting social roles, like relying on aged care services and support workers for help. Previously known for his active role in his community, Liam now struggles with isolation, as his friends may not understand his need for deeper support or his struggle to find a new identity without Helen by his side.

This highlights a few other social factors that we need to consider: social support and social roles. Worden (2009) cites research showing that high levels of perceived emotional and social support, both from within the family and in the community, are associated with reduced stress in the context of bereavement; conversely, those who experience complications in grieving often have inadequate or problematic support systems. It is important to note that the availability of social support has not been shown to accelerate the grieving process, but may “soften the blow” (Worden, 2009, p. 74). In addition, involvement in a wide range of social roles (e.g., family member; friend; employee; volunteer; member of community, religious, political, or activity group) has been found to enhance adjustment to loss (Worden, 2009).

Disenfranchised Grief

A key consequence of social and cultural factors is that particular loss experiences may not be recognised or validated. Disenfranchised grief refers to grief that people experience when they incur a loss that is not or cannot be openly acknowledged, publicly mourned, or socially supported. According to Doka (2009), there are several different ways by which grief may be disenfranchised and thus excluded from social support. Examples include where:

- The lost relationship was not considered valid, socially acceptable, or important within a family, community, or broader society (e.g., partner loss in same-sex couples, miscarriage).

- The loss itself is not recognised or viewed as significant (e.g., pet loss).

- The grieving person is exempted from rituals that might give meaning to the loss or is not seen as capable of grieving (e.g., children, or individuals with intellectual disabilities).

- Some aspects of the death or loss are stigmatising, embarrassing, or socially unacceptable (e.g., deaths from AIDS and suicide).

- The grief response or behaviour of the individual falls outside of social norms (e.g., highly expressive grief responses, few outward responses, talking to the deceased loved one).

One woman I was seeing had been having a long-term relationship with a married man, and although his wife knew about it, this woman had chosen not to tell her own friends or family. They believed he was just a friend. When he became ill and died, she was naturally grief-stricken. But there was a lot of confusion from others about why she was so distressed and needed a lot of time off work for example, because people weren’t aware of their relationship.

(Calvary Health Care, n.d.)

The implications for disenfranchised grief can include a lack of social acknowledgement of the loss, a social stigma applied to the bereaved person, and avoidance or lack of support.

Implications for Support Workers

For support workers, this scenario highlights the need for sensitivity to both practical and emotional aspects of grief, especially when societal expectations may discourage a client like Liam from expressing vulnerability. Support workers should recognise the role changes and reduced social support that may impact his well-being. Providing holistic care means not only assisting with daily tasks but also encouraging him to engage with social networks and offering opportunities to build new social roles that can aid in his adjustment and emotional healing.

7. Concurrent Stressors

Other factors that affect the grieving process include the changes, challenges, and crises that arise before, at the same time as, and following the loss (Worden, 2009). Changes and challenges occur for everyone, but multiple concurrent changes and stressors can be associated with greater difficulties after loss (think about the impacts of loss discussed in section one, including personal, social, and financial effects).

The stress vulnerability model (which we discussed earlier) can help identify the multiple stressors that clients may be experiencing as well as the stress incurred by a loss itself. This, combined with the person’s coping ability, vulnerabilities, and resources can help assess which clients are likely to be at higher risk of complex grief reactions and mental health issues.

In this section, you have learned about the theories and models that have been developed in attempts to understand and describe the grieving process and ways of supporting people after loss. As such, it is important to recognise and understand the factors that influence a particular person’s grief experience, particularly the individual factors and the sociocultural context in which the loss occurs. All of these factors will influence the support process and whether or not support is helpful. We turn our attention to providing loss and grief support next.

- Attig, T. (1996). How we grieve: Relearning the world. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Calvary Health Care. (n.d.) Bereavement across cultures: A resource for health professionals. Retrieved from https://www.caresearch.com.au/caresearch/Portals/0/Documents/PROFESSIONAL-GROUPS/Calvary_A5_real.pdf

- Doka, K. (2009). Disenfranchised grief. In Encyclopedia of death and the human experience (pp.379-381). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Hall, C. (2011). Beyond Kübler-Ross: Recent developments in our understanding of grief and bereavement. InPsych, 33(6). Retrieved from https://www.psychology.org.au/publications/inpsych/2011/december/hall/

- Harris, D. L. & Winokuer, H. R. (2016). Principles and practice of grief counseling. (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

- Humphrey, G. M & Zimpfer, D. G. (2008). Counselling for grief and bereavement. (2nd ed.). London, UK: Sage

- Klass, D. (2003). Grief and mourning in cross-cultural perspective. In The Macmillan encyclopedia of death and dying (pp. 382–389). New York, NY: Thompson.

- Korff, J. (2019). Mourning an Aboriginal death. Retrieved from https://www.creativespirits.info/aboriginalculture/people/mourning-an-aboriginal-death

- Kübler-Ross, E. (1969). On death and dying: What the dying have to teach doctors, nurses, clergy and their own families. New York, NY: Scribner.

- Lawton, S., & Lawton, K. (2012). Bereavement and primary care. In P. Wimpenny (Ed.), Grief, loss and bereavement (pp111-120). Oxon, UK: Routledge.

- Lewis, M., Feiring, C., & Rosenthal, S. (2000). Attachment over time. Child Development, 71(3), 707-720.

- Machin, L. (2009). Working with loss and grief: A new model for practitioners. London, UK: Sage

- Machin, L. (2014). Working with loss and grief: A theoretical and practical approach (2nd ed.). London, UK: Sage.

- McCoyd, J. M. L., & Walter, C. A. (2016). Grief and loss across the lifespan: A biopsychosocial perspective (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer.

- McLeod, K. & McLeod, J. (2011). Counselling skills: A practical guide for counsellors and helping professionals. (2nd ed.) New York, NY: Open University Press.

- MHPOD (n.d). The stress vulnerability model. Retrieved from http://www.mhpod.gov.au

- Murray, J. (2016). Understanding loss: A guide for caring for those facing adversity. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Neimeyer, R. A., Prigerson, H., & Davies, B. (2002). Mourning and meaning. American Behavioral Scientist, 46, 235–251.

- Neimeyer, R. A., Burke, L. A., Mackay, M. M., & van Dyke Stringer, J. G. (2010). Grief therapy and the reconstruction of meaning: From principles to practice. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 40, 73-83.

- Ober, A. M., Granello, D. H., & Wheaton, J. E. (2012). Grief counseling: An investigation of counselors’ training, experience, and competencies. Journal of Counseling & Development, 90(2), 150-159. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-6676.2012.00020.x

- Pomeroy, E., & Garcia, R. (2009). The grief assessment and intervention workbook: A strengths perspective. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole Cengage Learning.

- Stroebe, M., Gergen, M., Gergen, K., & Stroebe, W. (1996). Broken hearts of broken bonds? In D. Klass, P. R. Silverman & S. Nickman, S. (eds.). Continuing bonds: New understandings of grief. (pp. 31-43). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies, 23(3), 197-224.

- Walsh, F. (2007). Traumatic loss and major disasters: Strengthening family and community resilience. Family Process, 46, 207-227.

- Winokuer, H. R. & Harris, D. L. (2012). Principles and practice of grief counseling. New York, NY: Springer.

- Worden, J. W. (2009). Grief counseling and grief therapy. A handbook for the mental health practitioner. New York, NY: Springer Publication Company.