Readings in sections of the learning are associated with the units:

- Work with diverse people (CHCDIV001)

- Promote Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Cultural Safety (CHCDIV002)

Readings

- Reading A: Understanding and Applying Intercultural Communication in the Global Community

- Reading B: Cultural Diversity in Australia

- Reading C: Working with People from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Backgrounds

- Reading D: Communicating Effectively with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People

- Reading E: Why Cultural Safety Rather than Cultural Competency

- Reading F: White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack

- Reading G: Welcome to Country & Acknowledgement of Country

- Reading H: Working with Indigenous Children, Families, and Communities: Lessons from Practice

- Reading I: Creating Change Through Partnerships

- Reading J: Participatory Evaluation

All Case Histories in this text are presented as examples only and any comparison which might be made with persons either living or dead is purely coincidental.

McDaniel, E. R., & Samovar, L. A. (2015). Understanding and Applying Intercultural Communication in the Global Community: The Fundamentals. In L. A. Samovar, R. E., Porter, E. R., McDaniel, & C. S. Roy (Eds.) In Intercultural Communication: A Reader (14th ed.) (pp. 10-16).

What Culture Does

If we accept the idea that culture can be viewed as a set of social rules, its purpose becomes self-evident. Cultural rules provide a framework that gives meaning to events, objects, and people. The rules enable us to make sense of our surroundings and reduce uncertainty about the social environment. Recall the first time you were introduced to someone you were attracted to. You probably felt some level of nervousness because you wanted to make a positive impression. During the interaction you may have had a few thoughts about what to do and what not to do. Overall, you had a good idea of the proper courtesies, what to talk about, and generally how to behave. This is because you had learned the proper cultural rules of behavior by listening to and observing others. Now, take that same situation and imagine being introduced to a student from a different country, such as Jordan or Kenya. Would you know what to say and do? Would the cultural rules you had been learning since childhood be effective, or even appropriate, in this new social situation?

Culture also provides us with our identity, or sense of self. From childhood, we are inculcated with the idea of belonging to a variety of groups – family, community, church, sports teams, schools, and ethnicity – and these memberships form some of our different identities. Our cultural identity is derived from our “sense of belonging to a particular cultural or ethnic group” (Lustig & Koester, 2006, p. 3), which may be Chinese, Mexican American, African American, Greek, Egyptian, Jewish, or one or more of many, many other possibilities. Growing up, we learn the rules of social conduct appropriate to our specific cultural group, or groups in the case of multicultural families such as Vietnamese American, Italian American, or Russian American. Cultural identity can become especially prominent during interactions between people from different cultural groups, such as Pakistani Muslim and an Indian Hindu, who have been taught varied values, beliefs, and different sets of rules for social interaction. Thus, cultural identity can be a significant factor in the practice of intercultural communication.

Culture’s Components

While there are many explanations of what culture is and does, there is general agreement on what constitutes its major characteristics. An examination of these characteristics will provide increased understanding of this abstract, multifaceted concept and also offer insight into how communication is influenced by culture.

Culture is Learned

At birth, we have no knowledge of the many societal rules needed to function effectively in our culture, but we quickly begin to internalize this information. Through interactions, observations, and imitation, the proper ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving are communicated to us. Being taught to eat with a fork, a pair of chopsticks, or even one’s fingers is learning cultural behavior. Attending a Catholic mass on Sunday or praying at a Jewish Synagogue on Saturday is learning cultural behaviors and values. Celebrating Christmas, Kwanza, Ramadan, Yom Kippur is learning cultural traditions. Culture is also acquired from art, proverbs, folklore, history, religion, and a variety of other sources. This learning, often referred to an enculturation, is both conscious and subconscious and has the objective of teaching the individual how to function properly within a specific cultural environment.

Culture is Transmitted Intergenerationally

Spanish philosopher George Santayana wrote, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” He was certainly not referring to culture, which exists only if it is remembered and repeated by people. You learned your culture from family members, teachers, peers, books, personal observations, and a host of media sources. The appropriate way to act, what to say, and things to value were all communicated to the members of your generation by these many sources. You are also a source for passing these cultural expectations to succeeding generations, usually with little or no variation. Culture represents our link to the past and, through future generations, hope for the future. The critical factor in this equation is communication.

Culture Is Symbolic

Words, gestures, and images are merely symbols used to convey meaning. It is the ability to use these symbols that allows us to engage in the many forms of social intercourse used to construct and convey culture. Our symbol-making ability facilitates learning and enables transmission of meaning from one person to another, group to group, and generation to generation. In addition to transmission, the portability of symbols creates the ability to store information, which allows cultures to preserve what is considered important, and to create a history. The preservation of culture provides each new generation with a road map to follow and a reference library to consult when unknown situations are encountered. Succeeding generations may modify established behaviors or values, or construct new ones, but the accumulation of past traditions is what we know as culture.

Culture Is Dynamic

Despite its historical nature, culture is never static. Within a culture, new ideas, inventions, and exposure to other cultures create change. Discoveries such as the stirrup, gunpowder, the nautical compass, penicillin, and nuclear power are examples of culture’s susceptibility to innovation and new ideas. More recently, advances made by minority groups, the women’s movement, and gay rights advocates have significantly altered the fabric of contemporary U.S. society. Invention of the computer chip, the Internet, and the discovery of DNA have brought profound changes not only to U.S. culture but also to the rest of the world.

Diffusion, or cultural borrowing, is also a source of change. Think about how common pizza (Italian), sushi (Japanese), tacos (Mexican), and tandoori chicken and naan bread (India) are to the U.S. American diet. The Internet has accelerated cultural diffusion by making new knowledge and insights easily accessible. Immigrants bring their own cultural practices, traditions, and artifacts, some of which become incorporated into the culture of their new homeland, for example, Vietnamese noodle shops in the United States, Indian restaurants in England, or Japanese foods in Brazil.

Cultural calamity, such as war, political upheaval, or large-scale natural disasters, can cause change. U.S. intervention in Afghanistan is bringing greater equality to the women of that nation. For better or worse, the invasion of Iraq raised the influence of Shia and Kurdish cultural practices and lessened those of the Sunni. International emergency relief workers responding to the earthquake and tsunami disaster in Japan brought their own cultural practices to the situation, some of which no doubt became intermingled with the cultural practices of the local Japanese.

Immigration is a major source of cultural discussion. Many of the large U.S. urban centers now have areas unofficially, called Little Italy, Little Saigon, Little Tokyo, Korea Town, China Town, Little India, etc. These areas are usually home to restaurants, markets, and stores catering to a specific ethnic group. However, they also serve to introduce different cultural practices to other segments of the population.

Most of the changes, are often topical in nature, such as dress, food preference, modes of transportation, or housing. Values, ethics, morals, the importance of religion, or attitudes toward gender, age, and sexual orientation, which constitute the deep structures of culture, are far more resistant to major change and tend to endure from generation to generation.

Culture Is Ethnocentric

The strong sense of group identity, or attachment, produced by culture can also lead to ethnocentrism, the tendency to view one’s own culture as superior to others. Ethnocentrism can arise from enculturation. Being continually told that you live in the greatest country in the world or that the United States is “exceptional,” or that your way of life is better than those of other nations, or that your values are superior to those of other ethnic groups can lead to feelings of cultural superiority, especially among children. Ethnocentrism can also result from a lack of contact with other cultures. If exposed only to a U.S. cultural orientation, it is likely that you would develop the idea that your way of life was superior, and you would tend to view the rest of the world from that perspective.

An ability to understand or accept different ways and customs can also provoke feelings of ethnocentrism. It is quite natural to feel at ease with people who are like you and adhere to the same social norms and protocols. You know what to expect, and it is usually easy to communicate. It is also normal to feel uneasy when confronted with new and different social values, beliefs, and behaviors. You do not know what to expect, and communication is probably difficult. However, to view or evaluate those differences negatively simply because they vary from your expectations is a product of ethnocentrism, and an ethnocentric disposition is detrimental to effective intercultural communication.

Integrating Communication and Culture

There are a number of culture related components important in the study of intercultural communication. These include (1) perception, (2) patterns of cognition, (3) verbal behaviors, (4) nonverbal behaviors, and (5) the influence of context. Although each of these components will be discussed separately you must keep in mind that in an intercultural setting, all become integrated and function at the same time.

Perception

Every day we encounter an overwhelming amount of varied stimuli that we must cognitively process and assign a meaning. This procedure of selecting, organizing and evaluating stimuli is referred to as perception. The volume of environmental stimuli is far too large for us to pay attention to everything, so we select only what is considered relevant or interesting. After determining what we will attend to, the next step is to organize the selected stimuli for evaluation. Just as in this book, the university library, media news outlets, or Internet web sites, information must be given a structure before it can be interpreted. The third step of perception then involves evaluating and assigning meaning to the stimuli.

A common assumption is that people conduct their lives in accordance with how they perceive the world, and these perceptions are strongly influenced by culture. In other words, we see, hear, feel, taste, and even smell the world through the criteria that culture has placed on our perceptions. Thus, one’s idea of beauty, attitude toward the elderly, concept of self in relation to others, and even what tastes good and bad are culturally influenced and can vary among social groups. For example, Vegemite is a yeast extract spread used on toast and sandwiches that is sometimes referred to as the “national food” of Australia. Yet, few people other than those from Australia or New Zealand like the taste, or even the smell, of this salty, dark paste spread.

As you would expect, perception is a critical aspect of intercultural communication, because people from dissimilar cultures frequently perceive the world differently. Thus, it is important to be aware of the relevant socio-cultural elements that have a significant and direct influence on the meanings we assign to stimuli. These elements represent our belief, value, and attitude systems and our worldview.

Beliefs, Values, and Attitudes

Beliefs

can be defined as individually held subjective ideas about the nature of an object or event. These subjective ideas are, in large part, a product of culture, and they directly influence our behaviors. Bull fighting is generally thought to be cruel and inhumane by most people in the United States but many people in the Spain and Mexico consider it part of their cultural heritage. Strict adherents of Judaism and Islam believe eating pork is forbidden, but in China, pork is staple. In religion, many people believe there is only one god but others pay homage to multiple deities.

Values

Represent those things we hold important in life, such are morality, ethics, and aesthetics. We use values to distinguish between the desirable and the undesirable. Each person has a set of unique personal values and a set of cultural values. The latter are a reflection of the rules a culture has established to reduce uncertainty, lessen the likelihood of conflict, help in decision making, and provide structure to social organization and interactions. Cultural values are a motivating force behind our behaviors. Someone from a culture that places a high value on harmonious social relations, such as Korea and Japan, will likely employ an indirect communication style. In contrast, a U.S. American can be expected to use a more direct style because frankness, honesty, and openness are valued.

Attitudes

Our beliefs and values push us to hold certain attitudes, which are learned tendencies to act or respond in a specific way to events, objects, people, or orientations. Because culturally instilled beliefs and values exert a strong influence on attitudes, people tend to embrace what is liked and avoid what is disliked. Someone from a culture that considers cows sacred will surely take a negative attitude toward your invitation to have an Arby’s roast beef sandwich for lunch.

Worldview

Although quite abstract, the concept of worldview is among the most important elements of the perceptual attributes influencing intercultural communication. Stated simply, worldview is what forms an individual’s orientation toward such philosophical concepts as God, the universe, nature, and the like. Normally, worldview is deeply imbedded in one’s psyche and usually operates on a subconscious level. This can be problematic in an intercultural situation, where conflicting worldviews can come into play. As an example, many Asian and Native North American cultures hold a worldview that people should have a harmonious, symbiotic relationship with nature. In contrast, Euro-Americans are instilled with the concept that people must conquer and mold nature to conform to personal needs and desires. Individuals from nations possessing these two contrasting worldviews could well encounter difficulties when working to develop an international environmental protection plan. The concept of democracy, with everyone having an equal voice in government, is an integral part of the U.S. worldview. Contrast this with Afghanistan and parts of Africa where the worldview holds that one’s tribe or clan takes precedence over the central government.

Cognitive Patterns

Another important consideration in intercultural communication is the influence of culture on cognitive thinking patterns, which include reasoning and approaches to problem solving. Culture often produces different ways of knowing and doing. Research by Nisbett (2003) has demonstrated that Westerners use a linear, cause-and-effect thinking process, which places considerable value on logical reasoning and rationality. Thus, problems can be best solved by a systematic, in-depth analysis of each component, progressing individually from the simple to the more difficult. In contrast, Nisbett’s research disclosed that Northeast Asians (Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans) employ a holistic thinking pattern. They see problems as much more complex and interrelated, requiring a greater understanding of, and emphasis on, the collective rather than focusing separately on individual parts.

A culture’s normative thought patterns will influence the way individuals communicate and interact with each other. However, what is common in one culture may be problematic in another culture. As an illustration, in Japanese-U.S. business negotiations, the Japanese have a tendency to reopen previously discussed issues that the U.S. side considers resolved. United States negotiators find this practice to be frustrating and time consuming, believing that once a point has been agreed upon, it is completed. From the Japanese holistic perspective, however, new topics can have an influence on previously discussed points (McDaniel, 2000). This example demonstrates the importance of understanding that variant patterns of cognition exist and the need to learn how to accommodate them in an intercultural communication encounter.

Nonverbal Behavior

Another critical factor in intercultural communication is nonverbal behavior, which includes gestures, facial expressions, eye contact and gaze, posture and movement, touch, dress, silence, the use of space and time, objects and artifacts, and paralanguage. These nonverbal activities are inextricably intertwined with verbal behaviors and often carry as much or more meaning than the actual spoken words. As with language, culture also directly influences the use of, and meanings assigned to, nonverbal behavior. In intercultural communication, inappropriate or misused nonverbal behaviors can easily lead to misunderstandings and sometimes result in insults. A comprehensive examination of all nonverbal behavior is beyond the scope of this chapter, but we will draw on a few culturespecific examples to demonstrate their importance in intercultural communication exchanges.

Nonverbal greeting behaviors show remarkable variance across cultures. In the United States, a firm handshake among men is the norm, but in some Middle Eastern cultures, a gentle grip is used. In Mexico, acquaintances will often embrace (abrazo) each other after shaking hands. Longtime Russian male friends may engage in a bear hug and kiss each other on both cheeks. People from Japan and India traditionally bow to greet each other. Japanese men will place their hands at the side of the body and bow from the waist, with the lower-ranking person bowing first and dipping lower that the other person. Indians will perform the namaste, which entails holding the hands together in a prayer-like fashion at mid-chest while slightly bowing the head and shoulders.

Eye contact is another important culturally influenced nonverbal communication behavior. For U.S. Americans, direct eye contact is an important part of making a good impression during an interview. However, in some cultures, direct eye contact is considered rude or threatening. Among some Native Americans, children are taught to show adults respect by avoiding eye contact. When giving a presentation in Japan, it is common to see people in the audience with their eyes shut, because this is thought to facilitate listening. (Try it – you may be surprised.) How a person dresses also sends a strong nonverbal message. What are your thoughts when you see an elderly woman wearing a hijab, a Jewish boy with yarmulke, or a young black man in a colourful dashiki?

Nonverbal facial and body expressions, like language, form a coding system for constructing and expressing meaning, and these expressions are culture bound. Through culture, we learn which nonverbal behavior is proper for different social interactions. But what is appropriate and polite in one culture may be disrespectful or even insulting in another culture. People engaging in intercultural communication, therefore, should try to maintain a continual awareness of how body behaviors may influence an interaction.

Contextual Influences

We have defined culture as a set of rules established and used by a group of people to conduct social interactions. These rules determine what is considered correct communicative behavior, including both verbal and nonverbal elements, for both physical and social (situational) contexts. For example, you would not normally attend a funeral wearing shorts and tennis shoes or talk on your cell phone during the service. Your culture has taught you that these behaviors are contextually inappropriate (i.e., disrespectful).

Context is also an important consideration in intercultural communication interactions, where the rules for specific situations usually vary. What is appropriate in one culture is not necessarily correct in another. As an example, among most White U.S. Americans, church services are relatively serious occasions, but among African American congregations, services are traditionally more demonstrative, energetic gatherings. In a restaurant in Germany, the atmosphere is usually somewhat subdued, with customers engaging in quiet conversation. In Spain, however, the conversation is much louder and more animated. In U.S. universities, students are expected to interactively engage the instructor, but in Japan the expectation is that the instructor will simply lecture, with very little or no interaction.

In these examples, we see the importance of having an awareness of the cultural rules governing the context of an intercultural communication exchange. Unless all parties in the exchange are sensitive to how culture affects the contextual aspects of communication, difficulties will most certainly arise and could negate effective interaction.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2017). Cultural diversity in Australia: 2016 Census data summary

What is Cultural Diversity?

Cultural diversity relates to a person’s country of birth, their ancestry, the country of birth of their parents, what languages they speak, whether they are of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent, and their religious affiliation. The Census collects information on many characteristics that highlight the rich cultural diversity of Australian society.

Country of Birth

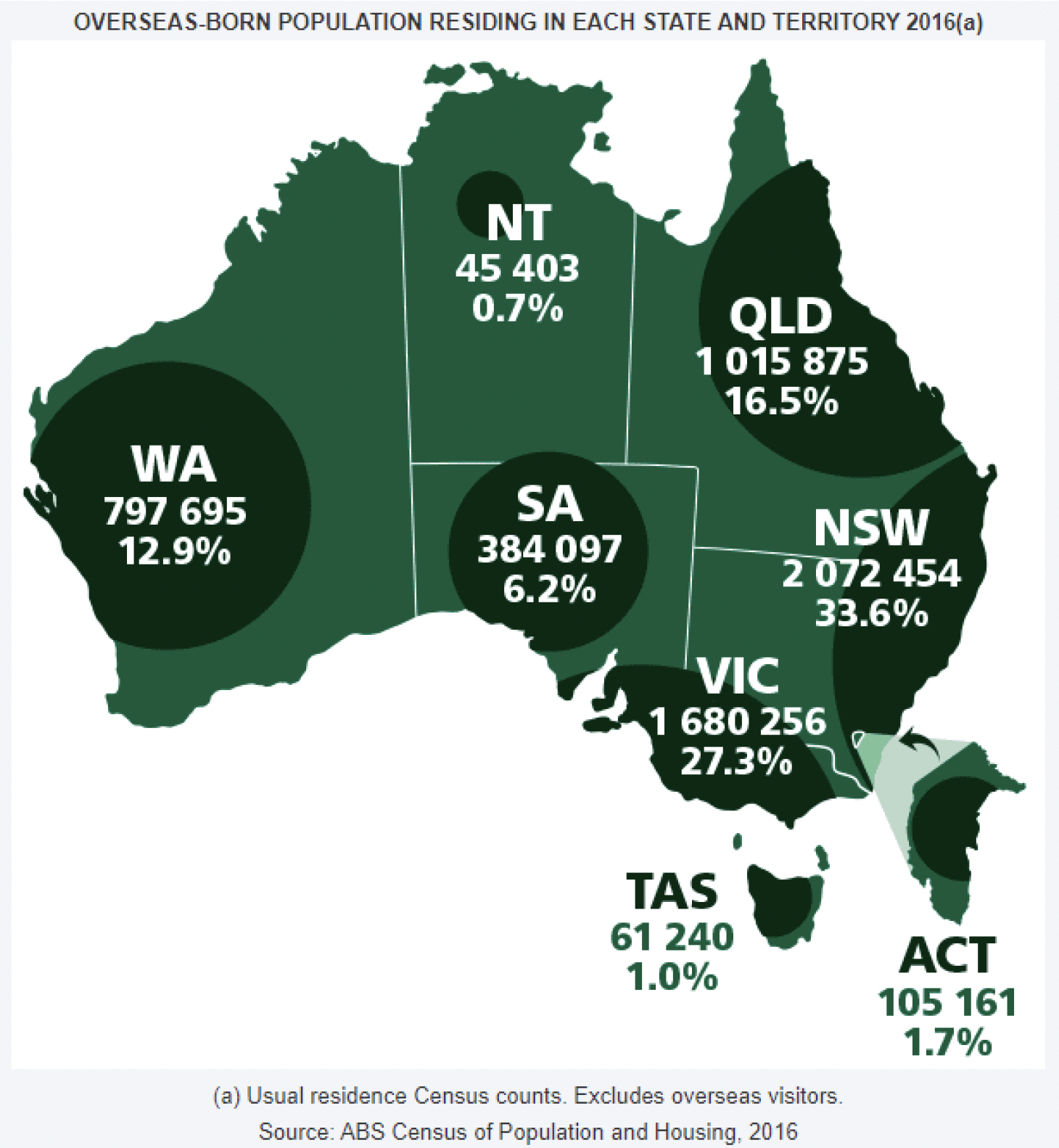

The 2016 Census shows that two thirds (67%) of the Australian population were born in Australia. Of the 6,163,667 overseas-born persons, nearly one in five (18%) had arrived since the start of 2012.

While England and New Zealand were still the next most common countries of birth after Australia, the proportion of those born overseas who were born in China and India has increased since 2011 (from 6.0% to 8.3%, and 5.6% to 7.4% respectively).

The Philippines has swapped places with Italy in the top 10 list, moving from number 8 to number 6.

Malaysia now appears in the top 10 countries of birth (replacing Scotland) and represents 0.6% of the Australian population.

| Top Five | 2011 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | % | ||

| 1 | Australia | 68.8 | 66.7 |

| 2 | England | 4.2 | 3.9 |

| 3 | New Zealand | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| 4 | China | 1.5 | 2.2 |

| 5 | India | 1.4 | 1.9 |

Ancestry

Ancestry is an indication of the cultural group that a person most closely identifies with.

Over 300 ancestries were separately identified in the 2016 Census. The most commonly reported ancestries were English (36%) and Australian (34%).

A further six of the leading ten ancestries reflected a European heritage. The two remaining ancestries in the top 10 were Chinese (5.6%) and Indian (4.6%).

Languages

In 2016, there were over 300 separately identified languages spoken in Australian homes. More than one-fifth (21%) of Australians spoke a language other than English at home.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

649 171 - 2.8% of the Australian population

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population has increased since 2011 from 2.5% to 2.8% of the Australian population. Further information on the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population is available in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Population data summary.

Religion

| Religous Affiliations Reported by the Australian Population, 2016 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Religous | Population ('000) | Population (%) | |

| Christian | 12 201.6 | 52.1 | |

| Other Religions | Islam | 604.2 | 2.6 |

| Buddhism | 563.7 | 2.4 | |

| Hinduism | 440.3 | 1.9 | |

| Sikhism | 125.9 | 0.5 | |

| Judaism | 91.0 | 0.4 | |

| Other | 95.7 | 0.4 | |

| Total | 1 920.8 | 8.2 | |

| No Religion a | 7 040.7 | 30.1 | |

| Australia b | 23 401.9 | 100.0 | |

a = No religion includes secular and other spiritual beliefs.

b = As religion was an optional question, the total for Australia will not equal the sum of the items above it.

In 2016, Christianity was the main religion reported in Australia (52%).

While the Islamic population made up only 2.6% of the total population, it was the second largest religion reported in the 2016 Census after Christianity. Islam was closely followed by Buddhism (2.4%).

The 'No Religion' count increased to almost a third of the Australian population between 2011 and 2016 (22% to 30%).

The Generations of Australians

In 2016, nearly half (49%) of Australians had either been born overseas (first generation Australian) or one or both parents had been born overseas (second generation Australian).

Where Migrants Live

For Australia's overseas-born population, New South Wales was still the most popular state or territory to live in 2016 (2,072,454 people or 34% of the overseas-born population).

Queensland Government (2010). Working with people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. (pp. 17-23).

There are no recipes or blueprints for working with people from specific cultural backgrounds (Diversity Training Manual, Immigrant Women’s Support Service, 2002: 120).

It is neither feasible nor appropriate to provide a prescriptive approach for working with people from specific ethnic, cultural or linguistic backgrounds. However based on the information and issues previously outlined in this paper, a number of effective approaches to practice are available for implementation by departmental officers, when intervening with children and families from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

Use appropriate terminology and avoid stereotyping

It is critical for staff working with children and families from a culture or ethnic group different from their own to recognise the uniqueness of all people and avoid stereotyping or making assumptions based on a person’s ethnicity, religion, culture or language. It is also important to be aware of the potential sensitivities around the use of some terminology.

Using terms such as “culturally and linguistically diverse”, “non-English speaking”, or “migrant” when referring to someone could be offensive as it may be taken to imply that the person is being categorised or is not part of the broader Australian community. For example, while it may be accurate to describe someone who has recently settled in Australia as a “migrant”, this would not be appropriate after a certain period of time unless the person chooses to self-identify in that way.

Develop cross-cultural competence

It would be wonderful if, with the wave of a magic wand, we could all possess the skills and attitudes that it takes to be cross-culturally effective. But, unfortunately, there are no shortcuts and there is no magic wand. Acquiring the skills is a lifelong process (Developing Cross-Cultural Competence, A Guide for Working with Children and Their Families, Lynch and Hanson, 2004: 73).

The term “cultural competence” is increasingly being used in relation to working effectively with people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. There are a number of different definitions provided for the term which typically include reference to organisational systems, policy and practice, as well as to individual workers.

The Standards for Cultural Competence in Social Work Practice published by the National Association of Social Workers (USA) state that:

“Cultural competence refers to the process by which individuals and systems respond respectfully and effectively to people of all cultures, languages, classes, race, ethnic backgrounds, religions, and other diversity factors in a manner that recognises, affirms, and values the worth of individuals, families, and communities and protects and preserves the dignity of each”.

While acknowledging both the individual and systemic/organisational context, this section focuses on the development of cultural competence at the individual level. Cultural competence at a personal level encompasses the worker’s attitudes, knowledge and skills, and requires an acceptance that long-term, ongoing and persistent development is required.

There are three key elements that are commonly identified in the development of cultural competence. These are:

- Developing cultural awareness, including self-awareness about one’s own culture

- Acquiring knowledge about other cultures

- Developing cross-cultural skills

Developing cultural awareness, including self-awareness

About one’s own culture, and associated values and assumptions on behaviour and interactions, is the first step towards developing cultural competence (Lynch and Hanson, 2004). This can often be difficult for people who belong to the dominant Anglo-Australian culture, as “culture” and “cultural diversity” are typically seen as pertaining to “others”. This process includes acknowledging any personal biases and stereotypes, recognising the influence of cultural norms and attitudes, and valuing cultural diversity and the validity of differing beliefs and values.

Acquiring knowledge about other cultures

Is another key element to developing cultural competence, and may be achieved by interacting with people from other cultural backgrounds in both professional and personal life, talking with service providers and community organisations who work with culturally diverse people, researching, watching films or documentaries or reading about other cultures and cultural diversity, and participating in workshops and seminars.

It is unrealistic to expect departmental officers to gain a thorough understanding about every cultural and ethnic group within Queensland. However, identifying the various cultural and ethnic communities that live in the area where you work and developing some understanding about their cultures is a useful starting point.

Developing cross-cultural skills

The third key element of cultural competency, includes:

- Effective cross-cultural communication

- Working with interpreters and translators

- Developing collaborative models with ethno-specific agencies and those working with people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds

- Establishing effective relationships with people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds

- Reflecting on and learning from each interaction with people from different cultures to inform future practice

- Monitoring access to services by people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds through data collection

- Identifying practices and systems that hinder cultural competency

- Identifying and implementing approaches that remove any barriers to working effectively with people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

As with the development of cultural knowledge, there are many ways in which these skills can be acquired. The development of cultural competence needs to be seen as an ongoing process, and every interaction with people from different cultures should be viewed as a learning experience.

Collect and record accurate information about cultural, linguistic and religious identity

How people identify themselves is a key to their self-image. For instance, a person born in Australia to Chinese parents may identify as Chinese, as Chinese Australian, or as Australian. It can lead to misunderstandings if practitioners assume rather than ask individuals how they identify themselves, and about the impact and influence of their cultural background on their life (from Diversity Training Manual, Immigrant Women’s Support Service, 2002: 118).

The identification and collection of accurate and complete information about the cultural, linguistic and religious backgrounds of children and families is critical to ensuring that the needs of the child can be appropriately met, as well as providing an important resource for service planning and for identifying any possible gaps in terms of access to child protection and family support services by parts of the community.

There are a number of provisions in the Child Protection Act 1999 about the need to take account of the ethnic, religious and cultural identity or values of the child. The timely collection of information is a prerequisite to ensuring that these provisions are met.

It is important not to make assumptions about a person’s cultural, linguistic or religious background and not to assume that a person’s country of birth is a reliable indicator of cultural identity. Give each individual the opportunity to self-identify this information by asking them to do so. If the person is unable to provide this information, for example due to a child’s young age, obtain the information from another reliable source, such as a parent.

At the same time, officers should be aware of potential difficulties that they may encounter when trying to collect this information. For example, some people may for various reasons be sensitive or suspicious about the purpose for collecting this information.

These cultural, linguistic and religious sensitivities may be able to be allayed by explaining that the information is being sought to ensure that the needs of the child and the child’s family can be appropriately responded to. Giving assurances about the department’s privacy and confidentiality policies may also assist.

The nature of information to be collected and recorded by departmental officers, when intervening with people from CALD backgrounds, is outlined in the Department of Communities, Child Safety Policy No. 458-2, Cultural Diversity Data Collection and Reporting.

Develop effective cross-cultural communication skills

Communication, both verbal and nonverbal, is critical to cross-cultural competence. Both sending messages and understanding messages that are received are pre-requisites to effective interpersonal interactions. Because language and culture are so inextricably bound, communicating with families from different cultural and/or sociocultural backgrounds is very complex (from Developing Cross-Cultural Competence, A Guide for Working with Children and Their Families, Lynch and Hanson, 2004: 61).

An understanding of some general principles and guidelines for effective cross-cultural communication can assist staff to be more effective when communicating with children and families from a cultural background different from their own. Lynch and Hanson (2004: 34) identify the importance of understanding that there are cultural differences in non-verbal communication, and of acknowledging cultural differences rather than minimising them in relation to cross-cultural communication.

Non-verbal communication can vary significantly across different cultures, and may sometimes even have an opposite meaning. For example, maintaining eye contact is valued during interpersonal interactions in most Anglo-based cultures, and is seen as conveying trustworthiness and sincerity. However, in a number of cultures, making eye contact with someone in authority is seen as a sign of disrespect, and in some cultures eye contact between strangers may be considered shameful. Similarly, smiling or laughing in some cultures may be used when describing an event that is confusing, embarrassing or even sad.

There are also cultural differences relating to physical proximity and social distance; touching and other physical contact; physical postures and gestures. Nodding a head is generally taken as a sign of understanding or agreement in mainstream Anglo-based cultures, however in some other cultures it may only signal an acknowledgment that you are speaking without implying either understanding or agreement. While it is not reasonable to expect anyone to know the range of non-verbal communication patterns across cultures, it is important to be aware of the potential for misunderstanding in these areas.

In some cultures there is a strong imperative to avoiding a display of disagreement and conflict. Individuals may appear to agree to a plan of action to avoid what they experience as an embarrassing or challenging situation, with no real capacity or intention to comply with the plan.

Acknowledging and respecting cultural differences rather than minimising them is important for effective cross-cultural communication, with the following characteristics being identified as common to effective cross-cultural communicators (Lynch and Hanson 2004):

- Having respect for people from other cultures

- Making continued and sincere attempts to understand the world from others’ points of view

- Being open to new learning

- Being flexible

- Having a sense of humour

- Tolerating ambiguity well

- Approaching others with a desire to learn.

Some other practical guidelines include:

- Use an accredited professional interpreter when a person is unable to communicate effectively in English (see below)

- Check and use correct pronunciation of names and the correct or preferred way of addressing a person (for example, formally or informally)

- Use plain English and clear enunciation

- Use concrete instead of abstract language and avoid the use of idioms, irony, sarcasm, slang and jargon

- Be patient, receptive and listen carefully to everything that is said

- Avoid any tendency to equate the person’s level of language skill or accent with level of intelligence or credibility

- Ask open-ended questions and be aware that the repeated “yes” answers may mean different things in different cultural contexts

- Make sure that the other person understands what you have said and that you understand what they have said. This can be done by asking the person to tell you what they have understood you have said and by paraphrasing back to them what you understand they have said.

Finally, it is useful to reflect on each cross-cultural interaction to identify those things that went well and areas that could be improved.

Utilise interpreters

The Queensland Government recognises that a significant number of people do not speak English at all or well enough to communicate adequately with officers of Queensland Government agencies… agencies should provide an interpreter in situations where a non-English speaking client has difficulty communicating in English (from Queensland Government Language Services Policy, 2004: 8).

Interpreters should be engaged in any situation where a child or family member has difficulty communicating in English. Wherever possible, a professional, qualified interpreter who has been accredited by the National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters (NAATI) should be used. They operate under a code of ethics and have been trained in areas such as maintaining confidentiality and accuracy.

As noted previously, children sometimes become proficient in English more quickly than their parents. However, as noted in the Queensland Government Language Services Policy, “Children and young relatives are not appropriate interpreters in any context.” (from Queensland Government Language Services Policy, 2004: 10). Similarly, the use of other family members or friends of the family as interpreters is also problematic and needs to be avoided. Some of the problems with using family members or friends as interpreters include the potential for embarrassment for all parties, and the increased risk of miscommunication and lack of privacy.

The need for an interpreter may not always be obvious, as some people may be able to converse at a basic level in English but not necessarily fully understand the language used by professionals. If there is any doubt about the person’s ability to fully comprehend what is being communicated, an interpreter should be used.

When engaging an interpreter it is important to confirm the language and dialect needs of the client, any gender preferences that they might have in relation to the interpreter and the preferred interpreting mode. Interpreting services may be available both on-site and through telephone interpreting.

Telephone interpreting has the benefits of being more readily available in regional areas and offering access to interpreters in a greater range of languages through a national network. On the other hand, on-site interpreting has the benefit of allowing for visual and non-verbal cues which can facilitate the communication, as well as the possibility of continuity as the same interpreter can be requested and used.

Another critical consideration when engaging an interpreter is to check that the interpreter is acceptable to the child and parents. In some circumstances, especially in smaller or emerging communities in which there are a limited number of accredited interpreters, the interpreter may be known to the child or family which could significantly inhibit or otherwise compromise the interaction.

Some suggested guidelines for staff when working with interpreters that are referred to in the literature include:

- Brief the interpreter beforehand wherever possible, explaining the purpose of the interview or meeting

- Allow for the extra time that is likely to be needed when using an interpreter

- Introduce yourself and the interpreter to the client and explain clearly who you are and what your role is

- Speak directly to the client rather than addressing the client through the interpreter and look at the client when speaking and listening to them

- Maintain control of the interview

- Pause often to allow the interpreter to speak

- Speak clearly and somewhat more slowly but not loudly

- Avoid using slang or technical jargon

- Make sure that the interpreter understands any difficult concepts that you are trying to convey

- Periodically check on the client’s understanding of what has been said by asking them, through the interpreter, to repeat in their own words what has been communicated

- Summarise what has been agreed during the meeting and check if the client has any questions

- Debrief the interpreter if necessary after the interview once the client has left.

Information about translating and interpreting services is available through the Multicultural Affairs Queensland website.

Establish links with service providers and ethnic community organisations

The insufficient partnership between the child safety services, community service providers in child safety and CALD communities was highlighted as a barrier to a better understanding of child safety legislation (from Changing the Wheels: Child Safety Concerns in Queensland, 2005:23).

There are a number of ethnic community organisations and service providers with strong links to people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds throughout Queensland. Establishing links with these services can assist departmental staff to develop their knowledge about working with diversity, as well as the particular needs of children and families. Establishing such links could lead to useful opportunities for working collaboratively to support children at risk and families, and facilitate appropriate referrals to relevant services. Bicultural support workers who can assist both families and departmental staff in their interactions may also be available.

When responding to specific child protection cases, ensure that the child and family’s privacy are protected and that informed consent is given for the involvement of an ethnic community organisation or service provider in each case.

For information about ethnic community organisations and service providers, refer to the Queensland Multicultural Resource Directory, available through the Multicultural Affairs Queensland website.

Queensland Health. (2015). Communicating effectively with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

This information sheet provides a general guide for communicating effectively with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Further information for communicating in the clinical context can be found in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Patient Care Guidelines.

Demonstrating Understanding

The negative impacts of racial and economic disadvantage and a series of past government policies, including segregation, displacement and separation of families has contributed to the mistrust held by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people towards government services and systems.

In today's Western dominant society, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people continue to be a marginalised and socially disadvantaged minority group. Compared to other Australians, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience significantly varied outcomes related to health, education, employment and housing. Discrimination, racism and lack of cultural understanding mean that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people still experience inequality and social injustice.

People's cultural beliefs, values and world-views influence thinking, behaviours and interactions with others. It is important to reflect without judgement before, during and after interacting with people whose beliefs, values, world-views and experiences are different to your own.

Personal Communication

Rapport

In many traditional cultures, a high sense of value is placed on building and maintaining relationships. Taking a 'person before business' approach will help form this relationship and build rapport.

- Introduce yourself in a warm and friendly way.

- Ask where people are you from, share stories about yourself or find other topics of common interest.

Language

Many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people do not speak English as their first language. Some also speak English in different dialects such as Kriol, Aboriginal English and Torres Strait Creole.

Some general tips to overcome language barriers may include:

- Avoid using complex words and jargon.

- Explain why you need to ask any questions.

- Always check you understood the meaning of words the person has used and vice versa.

- Use diagrams, models, dvds and images to explain concepts, instructions and terms.

- Be cautious about using traditional languages or creole words unless you have excellent understanding.

- If required, seek help from local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff.

Time

In Western culture, emphasis is placed on time to meet deadlines and schedules. Time is perceived differently in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, as more value is placed on family responsibilities and community relationships.

- Consider allocating flexible consultation times.

- Take the time to explain and do not rush the person.

Non-Verbal Communication

Some non-verbal communication cues (hand gestures, facial expressions etc.) used by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have different meanings in the Western context. Be mindful that your own non-verbal communication will be observed and interpreted. For example, feelings of annoyance may be reflected by your body language and are likely to be noticed.

Personal Space

Be conscious about the distance to which you are standing near a person. Standing too close to a person that you are unfamiliar with, or of the opposite gender, can make a person feel uncomfortable or threatened.

Touch

Always seek permission and explain to the person reasons why you need to touch them. Establish rapport first to make person feel comfortable.

Silence

In Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, extended periods of silence during conversations are considered the ‘norm’ and are valued. Silent pauses are used to listen, show respect or consensus. The positive use of silence should not be misinterpreted as lack of understanding, agreement or urgent concerns. Observe both the silence and body language to gauge when it is appropriate to start speaking. Be respectful and provide the person with adequate time. Seek clarification that what was asked or discussed was understood.

Eye Contact

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, avoidance of eye contact is customarily a gesture of respect. In Western society averting gaze can be viewed as being dishonest, rude or showing lack of interest. Some (but not all) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people may therefore be uncomfortable with direct eye contact, especially if unfamiliar. To make direct eye contact can be viewed as being rude, disrespectful or even aggressive. To convey polite respect, the appropriate approach would be to avert or lower your eyes in conversation.

- Observe the other person's body language.

- Follow the other person's lead and modify eye contact accordingly.

- Avoid cross-gender eye contact unless the person initiates it and is comfortable.

Titles

In Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, the terms ‘Aunty’ or ‘Uncle’ are used to show respect for someone older than you. This person does not have to be a blood relative or necessarily an Elder.

- Only address people with these titles if approval is given and/or a positive relationship exists.

Shame

‘Shame’ (deeply felt feelings of being ashamed or embarrassed) for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people may result from sharing private or personal information, cultural beliefs and from breaches of confidentiality.

- Take a discrete approach and avoid discussions in open or public spaces.

- Build trust and rapport to help people feel safe and comfortable with you and in their surroundings.

- Ensure confidentiality and consider Men’s and Women’s Business.

Listening

Explaining may take time because of narrative communication style or due to linguistic differences. The person may be struggling to communicate what they are trying to get across.

- Avoid selective hearing and ensure you are ‘actively’ listening.

- Paraphrase by summarising and repeating what the person said. This will help with clarification and signal you have been listening.

- Show empathy, be attentive and avoid continually interrupting or speaking over the person.

Questioning

In Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, indirect questioning is the approach most preferred. Direct questioning may lead to misunderstandings, discourage participation and make it difficult to obtain important information, particularly when a person is communicating in non-Standard English.

- Use indirect, 'round about' approaches (e.g. frame a question as a statement then allow time for the answer to be given).

- Clarify if the person understood the meanings of your words or questions and that you understood their answers.

- Avoid compound questions (e.g. "how often do you visit your GP and what are the reasons that you don’t?").

- Use plain words (e.g. say ‘start’ rather than ‘commence’).

- Do not ask the person to continually repeat themselves

- Avoid using hypothetical examples.

‘Yes’

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a tendency to agree with the questions even when they do not understand or agree, and may answer questions the way they think others want. People may say "yes" to questions to end the conversation so they can leave, to deal with other priorities, or because they simply feel uncomfortable.

- Take the time to build rapport to make the person feel comfortable.

- Explain at the beginning how long the appointment will take and give the person the opportunity to ask questions.

- If a person repeatedly says ‘yes’ immediately after a question, ask with respect what they understood from the questions and/or to explain reasons for their decision.

Clear instructions

It is critical to provide clear and full explanations so that the person fully understands your instructions. For example, to simply say “take until finished” - this may be misunderstood as “take until you feel better” rather than “take until all the tablets are finished”.

Provide options and ownership

When people are given choices and ownership over managing their health, the likelihood of medical compliance is increased.

- Provide options for care; for example, explain how some medications can be taken orally or by injection.

- Ensure that any options are practical and realistic.

- Do not make promises that you cannot deliver as this may create mistrust.

Making decisions

Due to family kinship structures and relationships, decision-making usually involves input by other family members.

- Check with the person if their decisions requires consultation with family.

- Allow time for information to be clearly understood.

- Be respectful if you are asked to leave the room or the meeting for matters to be discussed in private by the family

Communication assistance and cultural support

Build relationships within the local community and learn suitable and generally accepted words. Your local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander staff may be able to assist with cultural knowledge and interpreting information. They may also advise you of the best ways of distributing information through the community.

Curtis, E., Jones, R., Tipene-Leach, D., Walker, C., Loring, B., Paine, S. & Reid, P. (2019). Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18(174).

Introduction

Internationally, Indigenous and minoritorised ethnic groups experience inequities in their exposure to the determinants of health, access to and through healthcare and receipt of high quality healthcare [1]. The role of health providers and health systems in creating and maintaining these inequities is increasingly under investigation [2]. As such, the cultural competency and cultural safety of healthcare providers are now key areas of concern and issues around how to define these terms have become paramount, particularly within a Aotearoa New Zealand (NZ) context [3]. This article explores international literature to clarify the concepts of cultural competency and cultural safety in order to better inform both local and international contexts.

In NZ, Māori experience significant inequities in health compared to the non-Indigenous population. In 2010–2012, Māori life expectancy at birth was 7.3 years less than non-Māori [4] and Māori have on average the poorest health status of any ethnic group in NZ [5, 6]. Although Māori experience a high level of health care need, Māori receive less access to, and poorer care throughout, the full spectrum of health care services from preventative to tertiary care [7, 8]. This is reflected in lower levels of investigations, interventions, and medicines prescriptions when adjusted for need [8, 9]. Māori are consistently and significantly less likely to: get understandable answers to important questions asked of health professionals; have health conditions explained in understandable terms; or feel listened to by doctors or nurses [10]. The disturbing health and social context for Māori and significant inequities across multiple health and social indicators described above provide the ‘needs-based’ rationale for addressing Māori health inequities [8]. There are equally important ‘rights-based’ imperatives for addressing Indigenous health and health equity [11], that are reinforced by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples [12] and Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Treaty of Waitangi) in NZ.

There are multiple and complex factors that drive Indigenous and ethnic health inequities including a violent colonial history that resulted in decimation of the Māori population and the appropriation of Māori wealth and power, which in turn has led to Māori now having differential exposure to the determinants of health [13] [14] and inequities in access to health services and the quality of the care received. Framing ethnic health inequities as being predominantly driven by genetic, cultural or biological differences provides a limited platform for in-depth understanding [15, 16]. In addition, whilst socio-economic deprivation is associated with poorer health outcomes, inequities remain even after adjusting for socio-economic deprivation or position [17]. Health professionals and health care organisations are important contributors to racial and ethnic inequities in health care [2, 13]. The therapeutic relationship between a health provider and a patient is especially vulnerable to the influence of intentional or unintentional bias [18, 19] leading to the “paradox of well-intentioned physicians providing inequitable care [20]. Equitable care is further compromised by poor communication, a lack of partnership via participatory or shared decision-making, a lack of respect, familiarity or affiliation and an overall lack of trust [18]. Healthcare organisations can influence the structure of the healthcare environment to be less likely to facilitate implicit (and explicit) bias for health providers. Importantly, it is not lack of awareness about ‘the culture of other groups’ that is driving health care inequities - inequities are primarily due to unequal power relationships, unfair distribution of the social determinants of health, marginalisation, biases, unexamined privilege, and institutional racism [13]. Health professional education and health institutions therefore need to address these factors through health professional education and training, organisational policies and practices, as well as broader systemic and structural reform.

Eliminating Indigenous and ethnic health inequities requires addressing the social determinants of health inequities including institutional racism, in addition to ensuring a health care system that delivers appropriate and equitable care. There is growing recognition of the importance of cultural competency and cultural safety at both individual health practitioner and organisational levels to achieve equitable health care delivery. Some jurisdictions have included cultural competency in health professional licensing legislation [21], health professional accreditation standards, and pre-service and in-service training programmes [22,23,24,25]. However, there are mixed definitions and understandings of cultural competency and cultural safety, and how best to achieve them. This article reviews how concepts of cultural competency and cultural safety (and related terms such as cultural sensitivity, cultural humility etc) have been interpreted. The unintended consequences of a narrow or limited understanding of cultural competency are discussed, along with recommendations for why broader conceptualisation of these terms is needed to achieve health equity. A move to cultural safety is recommended, with a rationale for why this approach is necessary. We propose a definition for cultural safety and clarify the essential principles of this approach in healthcare organisations and workforce development.

Methods and Positioning

This review was originally conducted to inform the Medical Council of New Zealand, in reviewing and updating its approach to cultural competency requirements for medical practitioners in New Zealand Aotearoa. The review and its recommendations are based on the following methods:

- An international literature review on cultural competency and cultural safety.

- A review of cultural competency legislation, statements and initiatives in NZ, including of the Medical Council of New Zealand (MCNZ).

- Inputs from a national Symposium on Cultural Competence and Māori Health, convened for this purpose by the MCNZ and Te Ohu Rata o Aotearoa – Māori Medical Practitioners Association (Te ORA) [26].

- Consultation with Māori medical practitioners (through Te ORA).

The authors reflect expertise that includes Te ORA membership, membership of the Australasian Leaders in Indigenous Medical Education (LIME) (a network to ensure the quality and effectiveness of teaching and learning of Indigenous health in medical education), medical educationalist expertise and Indigenous medical practitioner and public health medicine expertise across Australia and NZ. This experience has been at the forefront of the development of cultural competency and cultural safety approaches within NZ. The analysis has been informed by the framework of van Ryn and colleagues [27] which frames health provider behaviour within a broader context of societal racism. They note the importance of shifting “the framing of the problem, from ‘the impact of patient race’ to the more accurate ‘impact of racism’….on clinician cognitions, behaviour, and clinical decision making” [27].

This review and analysis has been conducted from an Indigenous research positioning that draws from Kaupapa Māori theoretical and research approaches. Therefore, the positioning used to undertake this work aligns to effective Kaupapa Māori research practice that has been described by Curtis (2016) as: transformative; beneficial to Māori; under Māori control; informed by Māori knowledge; aligned with a structural determinants approach to critique issues of power, privilege and racism and promote social justice; non-victim-blaming and rejecting of cultural-deficit theories; emancipatory and supportive of decolonisation; accepting of diverse Māori realities and rejecting of cultural essentialism; an exemplar of excellence; and free to dream [28].

The literature review searched international journal databases and the grey literature. No year limits were applied to the original searching. Databases searched included: Medline, Psychinfo, Cochrane SR, ERIC, CINAHL, Scopus, Proquest, Google Scholar, EbscoHost and grey literature. Search terms included MeSH terms of cultural competence (key words: cultural safety, cultural awareness, cultural competence, cultural diversity, cultural understanding, knowledge, expertise, skill, responsiveness, respect, transcultural, multicultural, cross-cultur*); education (key words: Educat*, Traini*, Program*, Curricul*, Profession*, Course*, Intervention, Session, Workshop, Skill*, Instruc*, program evaluation); Health Provider (key words: provider, practitioner, health professional, physician, doctor, clinician, primary health care, health personnel, health provider, nurse); Health Services Indigenous (key words: health services Indigenous, ethnic* Minorit*, Indigenous people*, native people). A total of 51 articles were identified via the search above and an additional 8 articles were identified via the authors’ opportunistic searching. A total of 59 articles published between 1989 and 2018 were used to inform this review. Articles reviewed were sourced from the USA, Canada, Australia, NZ, Taiwan and Sweden (Additional file 1 Table S1).

In addition to clarifying concepts of cultural competence and cultural safety, a clearer understanding is required of how best to train and monitor for cultural safety within health workforce contexts. An assessment of the availability and effectiveness of tools and strategies to enhance cultural safety is beyond the scope of this review, but is the subject of a subsequent review in process.

Reviewing Cultural Competency

Cultural competency is a broad concept that has various definitions drawing from multiple frameworks. Overall, this concept has varying interpretations within and between countries (see Table 1 for specific examples). Introduced in the 1980s, cultural competency has been described as a recognised approach to improving the provision of healthcare to ethnic minority groups with the aim of reducing ethnic health disparities [31].

Table 1 Definitions and Concepts of Related Terms

| Terms | Definition/ Concept Examples | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Culture | The integrated pattern of human behaviour that includes thoughts, communications, actions, customs, beliefs, values, and institutions of a racial, ethnic, religious, or social group. | [29] |

| The accumulated socially acquired result of shared geography, time, ideas and human experience. Culture may or may not involve kinship, but meanings and understandings are collectively held by group members. Culture is dynamic and mobile and changes according to time, individuals and groups. | [30] | |

| There is a tendency within healthcare to equate culture with essentialized notions of race and ethnicity, which can lead to practices that separate culture from its social, economic and political context. Narrow conceptualizations of culture and identity may limit the effectiveness of particular approaches, and a focus on specific cultural information may inadvertently promote stereotyping. | [31] | |

| Cultural Awareness | a beginning step towards understanding that there is difference. Many people undergo courses designed to sensitise them to formal ritual rather than the emotional, social, economic and political context in which people exist | [30] |

| [is] concerned with having knowledge about cultural but, more specifically, ethnic diversity. | [32] | |

| an individual’s awareness of her/his own views such as ethnocentric, biased and prejudiced beliefs towards other cultures (p. e120) | [33] | |

| essentially the basic acknowledgment of differences between cultures | [34] | |

| recognizing that there are differences between cultures | [35] | |

| Cultural Sensitivity | alerts students to the legitimacy of difference and begins a process of self-exploration as the powerful bearers of their own life experience and realities and the impact this may have on others. | [30 |

| building on the awareness of difference through cultural acceptance, respect and understanding | [36] | |

| builds on cultural awareness’ acknowledgment of difference with the addition of the requirement of respecting other cultures | [34] | |

| where students start to analyse their own realities and the impact that this may have on others. | [35] | |

| Cultural Humility | incorporates a lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique, to redressing the power imbalances in the patient-physician dynamic, and to developing mutually beneficial and non-paternalistic clinical and advocacy partnerships with communities on behalf of individuals and defined populations. | [37] |

| entails valuing life-long learning and critical self-reflection, along with a respectful and inquisitive approach whereby practitioners are expected to seek knowledge from their clients regarding their cultural and structural influences rather than assuming understanding or expertise about a culture outside of their own | [38] | |

| defined as having an interpersonal stance that is other-oriented rather than self-focused, characterized by respect and lack of superiority toward an individual’s cultural background and experience. | [39] | |

| does not have an endpoint or goal; there is no objective of mastering another culture. Rather it is a continual process of self-reflection and self-critique that overtly addresses power inequities between providers and clients. Attaining cultural humility becomes not a goal but an active process, an ongoing way of being in the world and being in relationships with others and self. | [40] | |

| Cultural Security | it legitimises and values cultural differences to ensure no harm is caused and ultimately links understandings and actions | [41] |

| seeks to create interactions between health workers and health service users that do ‘not compromise the legitimate cultural rights, views, values and expectations of Aboriginal people’ | [42] | |

| Cultural Respect | The ‘Cultural Respect Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health 2004–2009’ identifies the goal of cultural respect as ‘uphold[ing] the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to maintain, protect and develop their culture and achieve equitable health outcomes | [42] |

| The model entails four basic elements highlighting the importance of ‘Knowledge and Awareness’ that informs ‘Skilled Practice and Behaviours’ as well as the development of ‘Strong Relationships’ between (health) institutions, individuals and communities in order to achieve an ‘Equity of Outcomes’ | [43] | |

| Cultural Adaptation | all modifications made to standard service methods in order to make services more acceptable, relevant, useful, and/or effective for diverse populations | [44] |

| Transcultural Competence | the ability to interact with clientele who come from a range of different cultural backgrounds | [43] |

| Transcultural Effectiveness | ability of organisations and systems ‘to acknowledge and respond to unique and diverse perspectives and support non- discriminatory practice’ (p. S51). These authors maintain, furthermore, that transculturally competent practitioners should recognise organisational and systemic obstacles and actively seek ways to modify them | [43] |

| Transcultural Nursing | Leininger (1994) defined transcultural nursing as being a subfield of nursing, focusing on comparative study and analysis of different cultures and is the basis on which the theory of culture care diversity and universality was formed. The goal of transcultural nurses being to “identify, test, understand and use a body of transcultural nursing knowledge and practices which is culturally derived in order to provide culturally specific nursing care to people” | [45] |

| Culturally Unsafe | “any actions that diminish, demean or disempower the cultural identity and well-being of an individual’ | [46, 47] |

| any action that diminishes, demeans, or disempowers the cultural identity and well-being of an individual | [48] | |

| Cultural Destructiveness | attitudes, policies, and practices that are destructive to cultures and consequently to the individuals within the culture such as cultural genocide | [29] |

| Cultural Incapacity | system or agencies that lack the capacity to help minority clients or communities due to extreme bias, paternalism and a belief in the racial superiority of the dominant group | [29] |

| Cultural Blindness | system or agencies that function with the belief that colour or culture make no difference and that all people are the same | [29] |

| Cultural Pre-competence | an agency that realises its weaknesses in serving minorities and attempts to improve some aspect of their services to a specific population | [29] |

| Cultural Proficiency | agencies that hold culture in high esteem, who seek to add to the knowledge base of culturally competent practice by conducting research and developing new therapeutic approaches based on culture | [29] |

One of the earliest [49] and most commonly cited definitions of cultural competency is sourced from a 1989 report authored by Cross and colleagues in the United States of America [29] (p.13):

Cultural competence is a set of congruent behaviours, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals and enable that system, agency, or those professionals to work effectively in cross-cultural situations.

Cross et al. [29] contextualized cultural competency as part of a continuum ranging from the most negative end of cultural destructiveness (e.g. attitudes, policies, and practices that are destructive to cultures and consequently to the individuals within the culture such as cultural genocide) to the most positive end of cultural proficiency (e.g. agencies that hold culture in high esteem, who seek to add to the knowledge base of culturally competent practice by conducting research and developing new therapeutic approaches based on culture). Other points along this continuum include: cultural incapacity, cultural blindness and cultural pre-competence (Table 1).

By the time that cultural competency became to be better understood in the late 1990s, there had been substantial growth in the number of definitions, conceptual frameworks and related terms [31, 50,51,52]. Table 1 provides a summary of the multiple, interchangeable, terms such as: cultural awareness; cultural sensitivity; cultural humility; cultural security; cultural respect; cultural adaptation; and transcultural competence or effectiveness. Unfortunately, this rapid growth in terminology and theoretical positioning(s), further confused by variations in policy uptake across the health sector, reduced the potential for a common, shared understanding of what cultural competency represents and therefore what interventions are required. Table 2 outlines the various definitions of cultural competency from the literature.

Table 2 Key Definitions and Concepts of Cultural Competency

| Terms | Definition/ Concept Examples | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural Competency | a set of congruent behaviours, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals and enable that system, agency, or those professionals to work effectively in cross-cultural situations. | [29] |

| acknowledges and incorporates - at all levels - the importance of culture, the assessment of cross-cultural relations, vigilance towards the dynamics that result from cultural differences, the expansion of cultural knowledge, and the adaptation of services to meet culturally-unique needs. | [29] | |

| a culturally competent counsellor must acquire ‘awareness, knowledge, and skills needed to function effectively in a pluralistic democratic society’, i.e., develop the ‘ability to communicate, interact, negotiate, and intervene on behalf of clients from diverse backgrounds | [43] | |

| the ability of individuals to establish effective interpersonal and working relationships that supersede cultural differences by recognizing the importance of social and cultural influences on patients, considering how these factors interact, and devising interventions that take these issues into account | [53] | |

| the ability of systems to provide care to patients with diverse values, beliefs and behaviours, including tailoring delivery to meet patients’ social, cultural, and linguistic needs | [54] | |

| a more comprehensive, skill-based concept that purposefully involves the system in addition to the patients and has been conceived of as an on-going quality improvement process, relevant across individual, organisational, systemic and professional levels | [50] | |

| a complex know-act grounded in critical reflection and action, which the health care professional draws upon to provide culturally safe, congruent, and effective care in partnership with individuals, families, and communities living health experiences, and which takes into account the social and political dimensions of care | [33] | |

| the ability to work and communicate effectively and appropriately with people from culturally different backgrounds. While appropriateness implies not violating the valued rules, effectiveness means achieving the valued goals and outcomes in intercultural interactions | [51] | |

| the ability to acknowledge, appreciate, and respect the values, preferences, and expressed needs of clients. Cultural competence is also the ability to resolve differences and identify solutions that reduce interference from various cultural factors…This article defines cultural competency as encompassing open-mindedness and a respect for people, families, and societies of various cultural backgrounds. Being able to translate this cultural knowledge and these skills into practice may help enhance the cultural appropriateness of healthcare. | [56] | |

| the development of a skill set for more effective provider-patient communication. They stressed the importance of providers’ understanding the relationship between cultural beliefs and behaviour and developing skills to improve quality of care to diverse populations. Several informants expressed concern about the persistence of stereotypic teaching strategies (such as treating Hispanics one way and African Americans another). They mentioned additional components that were underemphasized such as empathy, exploring socioeconomic issues, and addressing bias in the clinical encounter | [57] | |

| Social workers describe cultural competence as a continual process of striving to become increasingly self-aware, to value diversity, and to become knowledgeable about cultural strengths | [58] | |

| frequently approached in ways which limit its goals to knowledge of characteristics, cultural beliefs, and practices of different non-majority groups, and skills and attitudes of empathy and compassion in interviewing and communicating with non-majority groups. Achieving cultural competence is thus often viewed as a static outcome: One is “competent” in interacting with patients from diverse backgrounds much in the same way as one is competent in performing a physical exam or reading an EKG. | [23] | |

|