Reading A: ShapeManager’s Toolkit: The 13 Skills Managers Need to Succeed

Reading B: ShapeBudgeting Basics and Beyond (4th ed.)

Reading C: ShapeSeven Steps to a Successful Business Plan

Reading D: ShapeCoaching For Peak Employee Performance: A Practical Guide to Supporting Employee Development (2nd ed.)

Reading E: Management Accounting Best Practices: A Guide for the Professional Accountant

Reading F: Small Business for Dummies (4th ed.)

Reading G: Shape Australian GST Legislation with Overview (15th ed.)

Reading H: The Performance-Based Management Handbook

Reading I: Business Process Improvement Toolbox (2nd ed.)

Important note to students

The Readings contained in this Book of Readings are a collection of extracts from various books, articles and other publications. The Readings have been replicated exactly from their original source, meaning that any errors in the original document will be transferred into this Book of Readings. In addition, if a Reading originates from an American source, it will maintain its American spelling and terminology. The College is committed to providing you with high quality study materials and trusts that you will find these Readings beneficial and enjoyable.

Manager’s Toolkit: The 13 Skills Managers Need to Succeed

Harvard Business School

Boston, MA, 2004

PGS 219 – 242

What Is Budgeting?

Before you go on a trip, you fill your bag with the clothes, food, and money you’ll need. Budgeting is conceptually similar—planning your trip and ensuring that you’ll have sufficient resources to make it to your destination. An organization plans its journey toward strategic objectives in a similar fashion, and it prepares for the journey with an action plan called a budget. A budget can accomplish various tasks:

- Cover a short time span. For example, a start-up company develops a budget to ensure that it will have enough cash to cover operating expenses for twelve months or so.

- Take a long-term perspective. For example, a pharmaceutical firm builds a multiyear budget for developing a new product.

- Focus on required resources for a specific project. For example, if a manufacturing firm needs to install machinery to achieve production efficiencies, then its budget will anticipate the cost of the installation.

- Account for income as well as expenditures. For example, a retailer creates a profit plan based on an expected increase in sales.

So what is a budget? It is the translation of strategic plans into measurable quantities that express the expected resources required and anticipated returns over a certain period. A budget functions as an action plan. It may also present the estimated future financial statements of the organization. Finally, a budget is an adaptable tool for management to use to achieve its strategic goals.

Budget Functions

Budgets perform four basic functions, each critical to the success of a company in achieving its strategic objectives. These functions are planning, coordinating and communicating, monitoring progress, and evaluating performance.

Planning

Planning is a three-step process to ensure that the organization will have the resources available to achieve its goals:

- Choosing goals. The goals could be as comprehensive as the strategic mission of the organization. For example, as a manager at an Internet service provider (ISP), your goal could be “to be the most efficient provider of Internet services for our valued customers.” Or, as the general manager of a major-league baseball team, your goal could be specific and very focused: to increase revenues by 10 percent during the next quarter.

- Reviewing options and predicting results. Once the goals have been determined, the next step is to look at the options available for attaining the goals and predict what the most likely outcomes would be for each option. For example, if your goal as a manager at an ISP is to become the most efficient provider of Internet services, then you could opt to maintain state-of-the-art equipment at all times, train the most skilled repair teams in the field, or concentrate on providing the most timely customer service. Or, as a baseball team general manager planning to increase revenues by 10 percent, you could consider raising prices or expanding your marketing program. Thus, predicting the costs and benefits of each option is part of planning.

- Deciding on options. After an analysis of the potential costs and benefits of each option, the next step is to decide how to attain the desired goals. Choosing which options to implement establishes the direction the company will take. The budget reflects those decisions. As a manager at an ISP, for example, you may decide that, although the other two options are important, your focus should be on maintaining state-of-the-art equipment to provide the most efficient service for your customers. Or, as manager of the baseball team, you could decide that raising prices would most effectively bring in the specified increase in revenues.

Coordinating and Communicating

Coordination is the act of gathering the pieces together—the individual unit budgets or division budgets—and balancing and combining them to achieve the master budget that expresses the organization’s overall financial objectives and strategic goals. In many companies, this is quite a feat!

A master budget compiles the individual budgets from the functional areas of research and development, design, production, marketing, distribution, and customer service into one unit budget. Then the budgets from individual divisions, product lines, and subsidiaries are coordinated and integrated into a larger, cohesive result. Much like a composer weaving the music from many different instruments together to create a symphony, the master budget brings all the pieces together to achieve the organization’s overall strategic plan and company mission. Details of the master budget will be discussed later in this chapter.

To achieve this end, communication is essential. Upper management needs to communicate the company’s strategic objectives to all levels of the organization, and the individual planners need to communicate their particular needs, assumptions, expectations, and goals to those evaluating the departmental and functional budget pieces.

Additionally, the different groups within the company must always listen to one another. If one division is striving to achieve certain sales goals, then production must have that information to prepare for increased production capacity. If the company is introducing a new product, then the marketing department must be informed early in the planning process. The department will have to include in its budget the marketing efforts for the new product.

Monitoring Progress

Once the plan has been set in motion, the budget becomes a tool that managers can use to periodically monitor progress. They assess progress by comparing the actual results with the budget. This feedback, or monitoring and evaluation of progress, in turn allows for timely corrective action. If, on the one hand, the interim evaluation shows that the organization is right on target, with actual results matching the budget’s expected results, then no adjustment to the action plan is required. However, if you discover that the actual results differ from the expected results, then you must take corrective action. For example, if your baseball team’s goal is to increase revenues 10 percent by raising prices, but you find after one month that the fans are resistant to higher prices, then you might take corrective action by offering fans bonus packages to offset the negative impact of the higher prices.

The difference between the actual results and the results expected by the budget is called a variance. A variance can be favorable, when the actual results are better than expected, or unfavorable, when the actual results are worse than expected. For example, after the first month of the new baseball season, you evaluate how the ticket sales are proceeding (table 13-1).

Overall, unit tickets sales are lower than expected, but you observe that there is a favorable variance for the higher-priced infield box seats (ticket buyers don’t seem to mind the price hike for these seats).The biggest concern you have is the higher, unfavorable variance for the outfield grandstand seats. This is where you would concentrate your corrective action, because these fans seem to be responding to the higher prices by staying away. Thus, variance analysis can help you identify a problem early in the budget cycle and take the appropriate action.

TABLE 13-1: Ticket Sales Performance Report for April

| Average Tickets Sold per Game | |||

| Actual Results | Budgeted Amounts | Variance | |

| Infield Box | 2,500 | 2,000 | + 500; favorable |

| Grandstand | 6,850 | 7,000 | -150; unfavorable |

| Outfield Grandstand | 7,700 | 9,000 | - 1,300; unfavorable |

| Bleachers | 11,850 | 12,000 | - 150: unfavorable |

| Total | 28,900 | 30,000 | - 1,100; unfavorable |

Source: HMM Budgeting

Tip

Note here that we were strictly interested in units, not revenues. Managers could also conduct the budgeting exercise using revenues.

Evaluating Performance

Effective performance-evaluation systems contribute to the achievement of strategic goals, and budgets provide essential tools for measuring management performance. After all, a manager who makes basic planning and implementation decisions should be held accountable for the results. By comparing the actual results to the budget for a given period, an evaluator can determine the manager’s overall success in achieving his or her strategic goals. Performance evaluations serve a number of purposes:

- They motivate employees through reward systems based on performance.

- They provide the basis for compensation decisions, future assignments, and career advancement.

- They create a basis for future resource allocations.

Types of Budgets

The notion of the traditional budget has been under growing attack from those who believe that it no longer serves the needs of modern organizations. Critics complain that budgets are timed incorrectly (too long or too short), rely on inappropriate measures, and are either too simplistic (or too complex), too rigid in a changing business environment, or too unchallenging (for instance, the bar is deliberately set so that managers can hit their targets and collect their bonuses). Many budgets we’ll explore in this chapter were developed to address some of these difficult planning issues.

Short-Term Versus Long-Term Budgets

Budgets are typically developed to cover a one-year time span. But the period covered by a budget may vary according to the purpose of the budget, particularly as your company defines value creation. If an organization is concerned with the profitability of a product over its expected five-year life, then a five-year budget may be appropriate. If, on the other hand, a company is living hand-to-mouth, which is often the case with start-up companies, then a month-by-month budget that focuses on immediate cash flow might be more useful.

Fixed Versus Rolling Budgets

A fixed budget covers a specific time frame—usually one fiscal year. At the end of the year, a new budget is prepared for the following year. A fixed budget may be reviewed at regular intervals—perhaps quarterly—so that adjustments and corrections can be made if needed, but the basic budget remains the same throughout the period.

In an effort to address the problems of timeliness and rigidity in a fixed budget, some firms, particularly those in rapidly changing industries, have adopted a rolling budget. A rolling budget is a plan that is continually updated so that the time frame remains stable while the actual period covered by the budget changes. For example, as each month passes, the one-year rolling budget is extended by one month, so that there is always a one-year budget in place. The advantage of a rolling budget is that managers have to rethink the process and make changes each month or each period. The result is usually a more accurate, up-to-date budget incorporating the most current information.

The disadvantage of a rolling budget is that the planning process can become too time-consuming. Moreover, if a company reviews its budget on a regular basis (say, every quarter for a one-year budget), analyzes significant variances, and takes whatever corrective action is necessary, then the fixed budget truly isn’t as rigid as it seems.

Incremental Versus Zero-Based Budgeting

Incremental budgeting extrapolates from historical figures. Managers look at the previous period’s budget and actual results as well as expectations for the future in determining the budget for the next period.

For example, a marketing department’s budget would be based on the actual costs from the previous period but with increases for planned salary raises. The advantage of incremental budgeting is that history, experience, and future expectations are included in the development of the budget.

A disadvantage often cited by critics of the traditional budget is that managers may simply use the past period’s figures as a base and increase them by a set percentage for the following budget cycle rather than taking the time to evaluate the realities of the current and future marketplace. Managers can also develop a use-it-or-lose-it point of view, with which managers feel they must use all the budgeted expenditures by the end of the period so that the following period’s budget will not be reduced by the amount that would have been saved.

Zero-based budgeting describes a method that begins each new budgeting cycle from a zero base, or from the ground up, as though the budget were being prepared for the first time. Each budget cycle starts with a critical review of every assumption and proposed expenditure. The advantage of zero-based budgeting is that it requires managers to perform a much more in-depth analysis of each line item—considering objectives, exploring alternatives, and justifying their requests. The disadvantage of zero-based budgeting is that although it is more analytic and thorough, developing the budget can be extremely time-consuming, so much so that it may even interfere with actuating that budget. Planning needs to precede, but never overwhelm, action.

Kaizen Budgeting

Kaizen is a Japanese term that stands for continuous improvement, and Kaizen budgeting attempts to incorporate continuous improvement into the budgeting process. Cost reduction is built into the budget on an incremental basis so that continual efforts are made to reduce costs over time. If the budgeted cost reductions are not achieved, then extra attention is given to that operating area. For example, a manufacturing plant may budget a continuous reduction in the cost of components, as shown below, putting pressure on suppliers to find further cost reductions.

| January–February | $100.00 |

| February–March | $99.50 |

| March–April | $99.00 |

This type of incremental budgeting is difficult to maintain because the rate of budgeted cost reduction declines over time, making it more difficult to achieve improvements after the “easy” changes have been achieved.

The Master Budget

The master budget is the heart and soul of the budgeting process. It brings all the pieces together, incorporating the operating budget and the financial budget of an organization into one comprehensive picture. In other words, the master budget summarizes all the individual financial projections within an organization for a given period.

For a typical for-profit organization, the operating budget consists of the budgets from each function—such as research and development, design, production, marketing, distribution, and customer service—and provides the budgeted income statement. The financial budget includes the capital budget, the cash budget, the budgeted balance sheet, and the budgeted cash flows. The master budget must integrate both the operating budget and the financial budget through an iterative process during which information flows back and forth from each element of the master budget (see figure 13-1).

Master budgeting goes hand-in-hand with strategic planning at the highest level. Using the organization’s strategic goals as its foundation, the budget-building process is both chronological and iterative, moving back and forth, testing assumptions and options.

Before preparing a master budget, senior managers must ask these three important questions:

- Do the tactical plans being considered support the larger and longer-term strategic goals of the organization?

- Does the organization have, or have access to, the required resources—that is, the cash it needs to fund the activities throughout the immediate budget period?

- Will the organization create enough value to attract adequate future resources—profit, loans, investors, etc.—to achieve its longer-term goals?

Setting Assumptions

The first step in developing a budget is establishing a set of assumptions about the future. The assumptions that managers make will be directly affected by the answers to questions such as these:

- What are sales and marketing’s expectations for unit sales and revenues from new and existing products?

- Are supplier prices anticipated to rise or fall?

- What will be the cost of the company’s health-care plan for the coming year?

- If the unemployment rate is expected to decline, will the company need to raise salaries to ensure an adequate work force in a tight labor market?

- What will competitors do to gain market share?

Assumptions should be sought from the sources that have the best information. For example, top management has a clear view of the strategic goals, and the finance group has records of past financial performance and future economic trends. Look to the human resource group for information on shifts in the labor market, and the sales representatives for the best information about sales prospects. Likewise, the purchasing department has the latest information about suppliers and price trends. Developing assumptions is a companywide endeavor in which communication and coordination play a key role.

Tips for setting assumptions

- Use historical data as a starting point. Even when times are changing quickly, information about past performance can establish a base from which to begin.

- Trust your own experience. Make educated guesses where necessary about what is likely to happen in the future.

- Listen to your intuition. Even though you can’t verify those gut feelings, you can take them into account.

- Conduct due diligence. Seek out the information you need. This may involve doing research, reading trade journals, collecting industry statistics, and so on. And don’t forget that the Internet is a growing information resource.

- Talk with and listen to knowledgeable people. Discuss your ideas with team members, colleagues, mentors. Seek out industry participants, suppliers, concerned community leaders, and experts in the field. Engage in discussions with competitors.

- Learn when to be a risk taker and when to be conservative. In a volatile market, conservative assumptions may be the safest.

- Test your assumptions. If possible, try out your assumptions in small experiments before you accept them.

Preparing the Operating Budget

An operating budget is nothing more than an agreed-upon pact between top management and other members of the management team. It is a target, not a forecast. It specifies revenues and costs for the coming period.

These are expressed in a statement that resembles the income (or profit and loss) statement that every company generates. The essential difference is that we are building the statement from expected versus actual quantities. In a nutshell, the operating budget is structured as follows:

Revenues – (Cost of Goods Sold + Sales, General, and Administrative Costs) = Operating Income

We have divided the operating budget process into five simple steps.

Step 1: Calculate Your Expected Revenues

For the first step in preparing an operating budget, managers must apply some assumptions to forecast revenue growth (or decline). For our hypothetical for-profit company, Amalgamated Hat Rack, the managers of the Moose Head division translate their assumptions about revenue growth based on past performance and future expectations of sales for their products during the fiscal year (table 13-2).

If they take an incremental-budgeting approach, the managers will use the prior year’s actual sales of $1,228,100 as the base for developing their projections for the next year. If, on the other hand, they follow the zero-based budgeting method, they will make their sales projections for each model from the ground up, using forecasted economic data, predicted consumer behavior, and other information. These will take recent experience with customer behavior, economic forecasts, and other information into account.

Establishing projected revenue figures can create internal tensions. If managers are evaluated and rewarded on their achieving budgeted revenue targets, then they may be tempted to develop conservative revenue targets that will be easy to reach. This budgetary slack, or padding, provides a hedge for managers, making it more likely that actual revenues will be higher than budgeted revenues. With such results, the managers appear very effective.

TABLE 13-2: Moose Head Division, Amalgamated Hat Rack, Year 1 Budget

| Prior Year's Year 1 Actual | Budgeted Amounts | Rate of Change | |

| Sales by Model | |||

| Moose Antler Deluxe | $201,000 | $205,000 | 2.0% |

| Moose Antler Standard | $358,000 | $381,000 | 6.4% |

| Standard upright | $515,500 | $556,000 | 7.9% |

| Electro-revolving | $72,400 | $60,250 | -16.8% |

| Hall/wall model | $81,200 | $80,000 | -1.5% |

| Total sales | $1,228,100 | $1,282,250 | 4.4% |

| Cost of Goods Sold | |||

| Direct labor | $92,325 | $96,500 | 4.5% |

| Factory overhead | $6,755 | $7,200 | 7.0% |

| Direct materials | $211,000 | $220,284 | 4.4% |

| Total cost of goods sold | $310,080 | $323,984 | 4.5% |

| Marketing and Administrative Costs | |||

| Sales salaries | $320,000 | $331,200 | 3.5% |

| Advertising expenses | $145,000 | $151,000 | 4.1% |

| Miscellaneous selling expenses | $4,200 | $3,900 | -7.1% |

| Administrative expenses | $92,000 | $94,500 | 2.7% |

| Total SG&A | $561,200 | $580,000 | 3.46% |

| Operating Income | $355,820 | $377,666 | 6.14% |

Source: HMM Budgeting

Production constraints (the availability of qualified people for service firms and production capacity for manufacturers) may affect the revenue budget. If, for example, sales demand is expected to exceed the company’s ability to manufacture and distribute, then the revenue budget must be adjusted to match the production constraints rather than the actual demands of the market. Otherwise, the budget must add funds for building the capacity needed to meet demand.

Step 2: Calculate the Expected Cost of Goods Sold

Once the revenue budget has been established, managers can then develop the budget for the cost of goods sold. The total number of units to be produced will form the basis for determining the direct costs, including labor and materials. In the same way, the Moose Head division calculates the indirect factory costs or overhead as part of the cost of goods sold budget. Remember here that sales are budgeted to rise 4.4 percent to $1,282,250.

STEP 3: CALCULATE THE EXPECTED OTHER COSTS

Other nonproduction costs include costs generated by research and development, product design, marketing, distribution, customer service, and administration. For the Moose Head division, only various sales-related and administrative expenses make up the other-costs budget.

STEP 4: CALCULATE THE EXPECTED OPERATING INCOME

Finally, you can calculate the budgeted income statement. The difference between expected sales and expected costs results in the expected operating income. The managers of the Moose Head division provide their expected income statement to the top management of Amalgamated Hat Rack so that top management, in turn, can determine how the Moose Head division’s budget fits with the company’s master budget and overall strategic goals.

STEP 5: DEVELOP ALTERNATIVE SCENARIOS

Testing different scenarios is the “what if ” iterative process of budgeting. How will a change in one area affect the expected outcome? What if we increase advertising? How much would that increase sales? What if the Moose Head employees decide to go on strike? How can we incorporate that risk into the budget?

For example, Amalgamated’s management may decide to shift its strategic emphasis from increasing profits to developing a new product line in the Moose Head division. Moose Head managers would then develop another set of budget figures indicating research and development costs that would reduce the current budgeted operating income. Alternatively, Moose Head managers could decide to accept bids from a new group of suppliers that would in turn reduce materials expenditures and increase the budgeted operating income.

Creating Financial Budgets

Once managers of operations have developed their operating budgets, or expected income statements, financial managers then plan for the capital required to support those operating budgets. You can’t anticipate a 10 percent increase in sales, for example, without creating a parallel plan for the extra working capital and other inputs that will be required if the anticipated increase is realized. Three other budgets are developed:

- A cash budget that includes estimated cash from operations as well as other sources of cash (accounts payable, borrowing, or equity).The cash budget predicts and plans for the level and timing of cash inflow and outflow.

- An operating asset investment plan that ensures that adequate capital will be available for assets such as inventory and accounts receivable.

- A capital investment plan that budgets for proposed investments in long-term productive assets such as property, plant, and equipment expenditures and extended R&D programs.

These financial plans support the strategic objectives of the organization, planning for both the near-term (cash budget) and the long-term (capital investment plan) financial needs. They are expressed in forecasted (or pro forma) balance sheet and cash flow statements to form a complete picture of the organization’s expected financial position during the budget period.

The cash budget is particularly important for the firm’s financial managers since it indicates shortages or surpluses of cash in each period (usually months). No business can afford a shortfall of cash, as the company would be unable to pay bills as they come due. The cash budget shown in table 13-3 is one company’s simplified cash budget for a five-month period (January through May). Notice that it identifies all cash inflows and outflows for each month. The ending cash balance of a given month becomes the beginning balance for the next month. Thus, December’s $220 ending balance becomes January’s beginning cash balance. By adding the monthly surplus (or deficit) and the beginning cash balance, the budget finds the ending balance for the month. A glance across the bottom line indicates when the enterprise will encounter a cash shortfall, as happens here in April and becomes larger in May. Companies whose businesses are heavily seasonal—agricultural producers, garment makers, ski manufacturers, and so forth—routinely experience wide swings in ending cash balances.

TABLE 13-3: Simplified Cash Budget (in Thousands of Dollars)

| December | January | February | March | April | May | |

| Cash Inflows | ||||||

| Sales revenues | 1,100 | 875 | 600 | 500 | 600 | |

| Other revenues | 250 | 225 | 200 | 200 | 0 | |

| Interest income | 30 | 34 | 34 | |||

| Total inflows | 1,350 | 1,134 | 834 | 734 | 600 | |

| Cash Outflows | ||||||

| Purchases | 400 | 380 | 320 | 300 | 350 | |

| Salaries | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | 200 | |

| Hourly wages | 170 | 165 | 150 | 195 | 220 | |

| Health-care payments | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| Retirement contributions | 25 | 23 | 25 | 23 | 25 | |

| Interest payments | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | |

| Taxes | 305 | 295 | 270 | 260 | 240 | |

| Utilities | 20 | 18 | 15 | 20 | 25 | |

| Total outflows | 1,155 | 1,116 | 1,015 | 1,033 | 1,095 | |

| Cash Surplus or Deficit | 195 | 18 | (181) | (299) | (495) | |

| Beginning Balance | 220 | 415 | 433 | 252 | (47) | |

| Ending Balance | 220 | 415 | 433 | 252 | (47) | (542) |

During months of surplus, financial managers store cash in interest-bearing money market instruments such as short-term bank certificates of deposit (CDs), commercial paper, and U.S. Treasury bills.

As surpluses disappear, they convert those instruments back into cash and draw on lines of credit and short-term bank loans to eliminate any cash deficits. As you can see in table 13-3, managers must begin drawing on past surpluses in March. The surpluses have evaporated by April, forcing them to seek outside sources of cash. Seasonal and cyclical businesses use periods of heavy cash inflows to pay off their lines of credit and to build money market positions in anticipation of the next cash-consuming cycle.

Here are the steps to follow in building your own cash budget:

- Add receipts.–Determine the expected receipts—collections from customers and other sources—that will flow into the cash account each period. Cash collections may vary during the budget period. For example, many retail stores expect to receive most of their receipts during holiday seasons.

- Deduct disbursements.–Based on expected activity, calculate how much cash will be required to cover disbursements—cash payouts—during the period. Disbursements could include payment for materials, payroll, taxes due, and so on. Some of these expenditures may be evenly distributed throughout the budget period, but some, such as payroll and materials costs, may fluctuate as part of the production process.

- Calculate the cash surplus or deficiency.–To calculate the cash surplus or deficiency for a period, subtract the disbursements from the sum of the beginning cash balance and the receipts expected during that period.

- Add the beginning cash balance.–The beginning cash balance is the ending balance from the previous period. By adding them together, you have a new ending balance.

- Determine financing needed.–The ending balance will be positive or negative. A positive balance indicates that you have more than enough cash to cover operations during that period. A negative balance indicates that the company must develop a plan for financing the shortfall from other sources, such as a bank loan. Repayment of any such loan must be reflected among the cash outflows of subsequent budget periods.

The Human Side of Budgeting

To some degree, preparing a budget is a matter of crunching numbers, a process being left more and more to financial modeling software, computers, and technology. But behind those numbers are real people like you—people who make assumptions, people who think about future situations, people who understand the idiosyncrasies of customers and competitors. Ideally, everyone involved in the budget process has the same goal in mind—achieving the organization’s strategic objectives.

What some may see as a straightforward, even mechanical, process, however, is in reality complicated by genuine disagreements over assumptions about future trends and events, by conflicting needs, and by individual agendas that overshadow the larger corporate good. For this reason, the budget process can be defined as a series of negotiations between disparate interests. Top management wants the highest possible economic value in terms of profit. Middle management may have contrary needs, such as new equipment or new personnel. The human element is what can make the budget process so engaging and, at times, so frustrating.

Top-Down Versus Participatory Budgeting

Top-down budgeting describes the process whereby upper management sets budget goals—revenue, profit, and so on—and imposes these goals on the rest of the organization. Thus, for example, the CEO of Amalgamated Hat Rack gives Moose Head manager Claude Cervidés the goal of attaining an operating profit—or earnings before interest and taxes—of $400,000 for the upcoming fiscal year. It’s then up to Claude to shape his operating budget with $400,000 as the operating profit target.

Top-down budgeting has many advantages. Since senior management has a clearer concept of the organization’s strategic objectives, topdown budgeting ensures the following benefits for senior management:

- Budget goals that reflect management’s larger strategic objectives

- Better coordination of the budget requirements for all the elements of the organization

- The discouragement of “padding” managers’ unit budgets

- High goals that challenge managers to stretch

Top-down budgeting has two main disadvantages. First, upper management may be out of touch with the realities of the individual divisions’ production processes or markets. As a result, the goals they set may be inappropriate or unattainable. Second, middle managers may feel left out of the decision-making process and, consciously or unconsciously, may not fully participate in achieving the budgeted goals.

With participatory budgeting, the people responsible for achieving the budget goals are included in goal setting. Cervidés, for instance, would develop the budget for his own division, with the active participation of the heads of purchasing, human resources, production, marketing, and administration. Once his team had completed the budget, Cervidés would send it to Amalgamated Hat Rack’s senior management. After review and possible feedback to Cervidés, they would incorporate Moose Head’s budget, along with all the other budgets, into the master budget.

One advantage of participatory budgeting is that the people closest to the line activities—people who presumably have the best information—make the budget decisions. Also, participants in this type of budget process are more likely to make the extra effort to achieve the budgeted goals. The disadvantages of participatory budgeting are also twofold. First, the people closest to the line activities may not see the larger strategic picture. Second, if performance evaluations are tied to budget achievement, then the managers will have an incentive to pad their budgets either by underestimating revenues or by overestimating costs.

Tips for negotiating your team’s budget

Effective budgeting requires a certain organizational savvy. Here are some tips for dealing with organizational issues that surround the budgeting process:

- Understand your organization’s budgeting process. What guidelines must you follow? What is the timing of the budget process? How is the budget used in the organization?

- Communicate often with the controller or finance person in your department. Ask questions about points you don’t understand. Get that person’s advice about the assumptions your team is making.

- Know what real concerns are driving the people making the decisions about your budget. Be sure to address those concerns.

- Get buy-in from the decision makers. Spend time educating the finance person or decision maker about your area of the business. This will lay the groundwork for implementing changes later.

- Understand each line item in the budget you’re working on. If you don’t know what something means or where a number comes from, find out yourself. Walk the floor. Talk to people on the line.

- Have an ongoing discussion with your team throughout the budget period. The more you plan, the more you will be able to respond to unplanned contingencies.

- Avoid unpleasant surprises. As the numbers become available, compare actual figures to the budgeted amounts. If there is a significant or an unexpected variance, find out why. And be sure to notify the finance person who needs to know.

Iterative budgeting is an attempt to combine the best of both top-down and participatory budgeting. In the initial step, senior management provides the unit heads with a clear understanding of the organization’s strategic goals. The unit heads then work with their teams to develop operating budgets that incorporate both their own tactical goals and the organization’s larger strategic goals. After the unit heads send their budget proposals to upper management, upper management reviews the individual budgets and may ask for adjustments. And the negotiating process continues back and forth until a final master budget is achieved. The key to success in this and other budgeting processes is communication. Senior management has to communicate strategic goals in a way that makes sense. In turn, the unit heads communicate their resource needs and concerns when presenting budget proposals to management. All participants in the budget process have an obligation to listen to the various and sometimes conflicting positions.

Slack

Budgetary slack, or padding, occurs when managers believe they are going to be evaluated on their performance relative to the budget. To ensure that they will achieve their budgeted figures and be rewarded, they budget revenues conservatively or exaggerate anticipated costs, or do both. Both actions make the budget “game” easier to win. Budgetary slack also provides these managers with a hedge against unexpected problems, reducing the risk that they will fail to “make their numbers.” It’s an old game that managers at all levels learn to play. The big losers, of course, are the owners of the business.

What-If Scenarios and Sensitivity Analysis

Budgets are only as good as the future assumptions on which they are based. But assumptions are often wrong. We assume that customer A will purchase ten thousand units from us next year—and we have the sales agreement to back it up. But if customer A experiences a major business collapse, then that sales agreement isn’t worth much. We assume that our energy bills will increase at roughly the current rate of inflation. But guess what? A cold winter and huge demand for energy could push prices through the roof.

Sensitivity analysis is an approach to dealing with assumptions and alternative options. As a budgetary tool, this analysis can greatly enhance the value of budgets as instruments for planning, feedback, and course correction. A sensitivity analysis applies a what-if situation to the budget model to see the effect of the potential change on the original data. For example, what if the cost of materials rises 5 percent, or what if sales rise 10 percent? Software packages for financial planning are available and commonly used to perform these calculations, giving managers a powerful tool to estimate the costs and benefits of various options and possibilities.

For example, if the Moose Head division wanted to test its assumptions with what-if scenarios, it could determine the effect of some likely alternative scenarios (table 13-4).Given the results of these analyses, Claude Cervidés may decide to direct his efforts toward lowering materials costs to achieve the best bottom-line result.

Tips for Effective Budgeting

If you want to use budgeting as a planning and team-building tool, you need to develop a game plan. Even if you recently finished this year’s budget, it’s not too early to start thinking about next year. Here are a few points to keep in mind:

- If you’re a new manager, become familiar with your company’s budgeting process.

- Spend time learning and understanding company priorities, as well as helping your team understand them.

- Make sure that any request for funds is in sync with the objectives set by senior management.

- Determine your unit’s cost per output, however defined.

- Ask for volunteers to research line items. This will make your job easier and give subordinates opportunities to learn about the budgeting process.

- If you need to reduce costs, identify the activities that add value for the customer and those that don’t. Analyze the cost of each, and begin by cutting non-value-added activities.

- Show how your budget request will generate income for the company. In other words, your budget should not be so much a request for funds as a proposal showing how you will help the company realize its goals.

TABLE 13-4: Moose Head Division, Amalgamated Hat Rack, Sensitivity Analysis of Several Options

| What-If Scenarios | Units Sold | Direct Materials Cost | Operating Income |

|---|---|---|---|

| Budget model | 21,400 | $214,000 | $383,950 |

| Scenario 1: increase unit sales 10% | 23,540 | $235,000 | $422,730 |

| Scenario 2: decrease unit sales 5% | 20,330 | $203,300 | $360,900 |

| Scenario 3: decrease materials cost 5% | 21,400 | $203,300 | $398,700 |

Source: HMM Budgeting

Summing Up

- The four basic functions of budgets are planning, coordinating and communicating, monitoring progress, and evaluating performance.

- Budgets help an organization move forward and keep on track. And they make the time and trouble associated with budgeting worthwhile.

- The master budget brings together operating and cash budgets and various financial projections into a comprehensive picture.

- What-if scenarios and sensitivity analysis can help budget makers predict the effects of specific changes in any important assumptions built in to the budget.

Budgeting Basics and Beyond (4th ed.)

Jae K Shim, Joel G Siegel and Allison Shim

John Wiley and Sons

Hoboken, NJ, 2011

PGS 95 – 118

Master Budget—Genesis of Financial Forecasting and Profit Planning

Overview

A comprehensive—master—budget is a formal statement of management's expectations regarding sales, expenses, volume, and other financial transactions for the coming period. It consists basically of a pro forma income statement, pro forma balance sheet, and cash budget.

At the beginning of the period, the budget is a plan or standard. At the end, it serves as a control device to help management measure its performance against the plan so that future performance may be improved.

With the aid of computer technology, budgeting can be used as an effective device for evaluation of what-if scenarios. Management can find the best course of action among various alternatives through simulation. If management does not like what it sees on the budgeted financial statements in terms of financial ratios such as liquidity, activity (turnover), leverage, profit margin, and market value ratios, it can always alter its contemplated decision and planning set.

The budget is classified broadly into two categories:

- Operating budget

- Financial budget

The operating budget consists of:

- Sales budget

- Production budget

- Direct materials budget

- Direct labor budget

- Factory overhead budget

- Selling and administrative expense budget

- Pro forma income statement

The financial budget consists of:

- Cash budget

- Pro forma balance sheet

The five major steps in preparing the budget are:

- Prepare a sales forecast.

- Determine expected production volume.

- Estimate manufacturing costs and operating expenses.

- Determine cash flow and other financial effects.

- Formulate projected financial statements.

Exhibit 6.1 presents a master budget.

COMPREHENSIVE SALES PLANNING

Chapter 5 gave an overview of a comprehensive profit plan. The initiating management decisions in developing the plan were the statements of broad objectives, specific goals, basic strategies, and planning premises. The sales planning process is a necessary part of profit planning and control because (1) it provides for the basic management decisions about marketing and (2), based on those decisions, it is an organized approach for developing a comprehensive sales plan. If the sales plan is not realistic, most if not all of the other parts of the overall profit plan also are not realistic. Therefore, if management believes that a realistic sales plan cannot be developed, there is little justification for profit planning and control. Despite the views of a particular management, such a conclusion may be an implicit admission of incompetence. Simply put, if it were really impossible to assess the future revenue potential of a business, there would be little incentive for investment in the business initially or for its continuation, except for purely speculative ventures that most managers and investors prefer to avoid.

The primary purposes of a sales plan are (1) to reduce uncertainty about the future revenues, (2) to incorporate management judgments and decisions into the planning process (e.g., in the marketing plans), (3) to provide necessary information for developing other elements of a comprehensive profit plan, and (4) to facilitate management's control of sales activities.

Sales Planning Compared with Forecasting

Sales planning and forecasting often are confused. Although related, they have distinctly different purposes. A forecast is not a plan; rather it is a statement and/or a quantified assessment of future conditions about a particular subject (e.g., sales revenue) based on one or more explicit assumptions. A forecast should always state the assumptions on which it is based. A forecast should be viewed as only one input into the development of a sales plan. The management of a company may accept, modify, or reject the forecast. In contrast, a sales plan incorporates management decisions that are based on the forecast, other inputs, and management judgments about such related items as sales volume, prices, sales effects, production, and financing.

Testing the Top Line

Most companies do not really manage top-line growth. They allocate resources to businesses they think will be most productive and hope the economy cooperates. But a growing number of companies are taking a less passive approach and studying revenue growth more carefully. They argue that quantifying the sources of revenue can yield a wealth of information, which results in more targeted and more effective decision making. With the right discipline and analysis, they say, growing revenues can be as straightforward as cutting costs. Some companies go so far as to link the two efforts. The idea is to bring the same systematic analysis to growing revenue that we have brought to cost cutting.

A sources-of-revenue statement (SRS) is useful in this effort. The information on revenue captured by traditional financial statements is woefully inadequate. Sorting revenues by geographic market, business unit, or product line tells the source of sales. But it does not explain the underlying reason for those sales.

The SRS model breaks revenue into five categories:

- Continuing sales to established customers (known as base retention)

- Sales won from the competition (share gain)

- New sales from expanding markets

- Moves into adjacent markets where core capabilities can be leveraged

- Entirely new lines of business unrelated to the core

To produce an SRS statement, five steps are required in addition to establishing total revenues for comparable periods, as is commonly done for purposes of completing an income statement:

- Determine revenue from the core business by establishing the revenue gain or loss from entry to or exit from adjacent markets and the revenue gain from new lines of business, and subtracting this from total revenue.

- Determine growth attributable to market positioning by estimating the market growth rate for the current period and multiplying this by the prior period's core revenue.

- Determine the revenue not attributable to market growth by subtracting the amount determined in Step 2 from that determined in Step 1.

- To calculate base retention revenue, estimate the customer churn rate, multiply it by the prior period's core revenue, and deduct this from the prior period's core revenue.

- To determine revenue from market-share gain, subtract retention revenue, growth attributable to market positioning, and growth from new lines of business and from adjacent markets from core revenue

Example 1

To illustrate how all these budgets are put together, we will focus on a manufacturing company called the Putnam Company, which produces and markets a single product. The budget process to be used in this chapter is often called functional budgeting because the focus is on preparing budgets by function, such as manufacturing, selling, and general and administrative support.

We will make these assumptions:

- The company uses a single material and one type of labor in the manufacture of the product.

- It prepares a master budget on a quarterly basis.

- Work-in-process inventories at the beginning and end of the year are negligible and are ignored.

- The company uses a single cost driver—direct labor hours (DLH)—as the allocation base for assigning all factory overhead costs to the product.

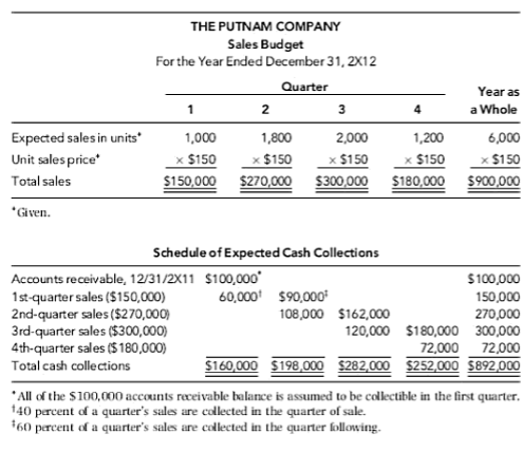

SALES BUDGET

The sales budget is the starting point in preparing the master budget, since estimated sales volume influences nearly all other items appearing throughout the master budget. The sales budget should show total sales in quantity and value. The expected total sales can be break-even or target income sales or projected sales. It may be analyzed further by product, by territory, by customer, and, of course, by seasonal pattern of expected sales.

Generally, the sales budget includes a computation of expected cash collections from credit sales, which will be used later for cash budgeting.

Schedule 1

MONTHLY CASH COLLECTIONS FROM CUSTOMERS

Frequently, there are time lags between monthly sales made on account and their related monthly cash collections. For example, in any month, credit sales are collected in this manner: 15 percent in month of sale, 60 percent in the following month, 24 percent in the month after, and the remaining 1 percent are uncollectible.

| April-Actual | May-Actual | June-Budgeted | July-Budgeted | |

| Credit sales | $320 | $200 | $300 | $280 |

The budgeted cash receipts for June and July are computed:

| For June: | ||

| From April sales | $320 × 0.24 | $76.80 |

| From May sales | $200 × 0.6 | $120.00 |

| From June sales | $300 × 0.15 | $45.00 |

| Total budgeted collections in June | $241.80 | |

| For July: | ||

| From May sales | $200 × 0.24 | $48.00 |

| From June sales | $300 × 0.6 | $180.00 |

| From July sales | $280 × 0.15 | $42.00 |

| Total budgeted collections in July | $270.00 | |

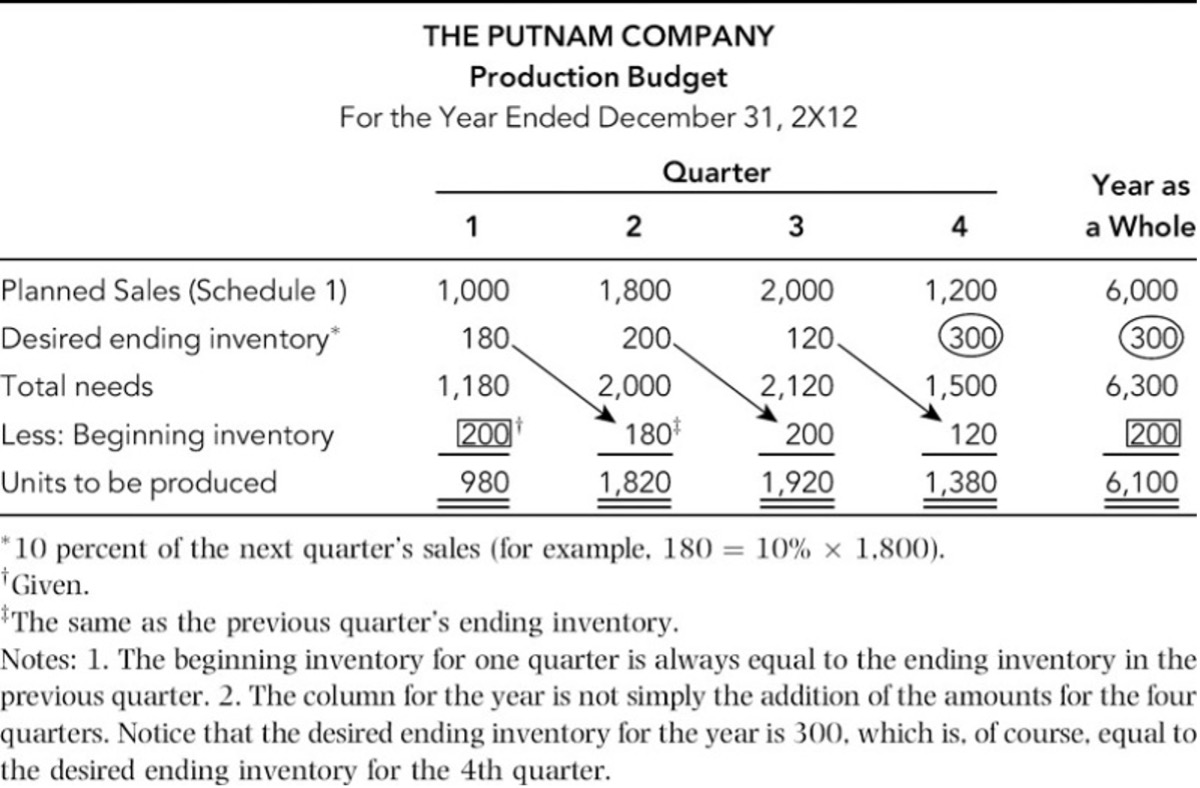

PRODUCTION BUDGET

After sales are budgeted, the production budget can be determined. The production budget is a statement of the output by product and is generally expressed in units. It should take into account the sales budget, plant capacity, whether stocks are to be increased or decreased, and outside purchases.

The number of units expected to be manufactured to meet budgeted sales and inventory requirements is set forth in the production budget. In the just-in-time (JIT) firm, there are no inventory requirements, since a customer triggers production. Note that the production budget is expressed in terms of units. At this juncture, we do not know how much they will cost.

Expected production volume = Planning sales + Desired ending inventory – Beginning inventory

The production budget is illustrated in Schedule 2.

Schedule 2

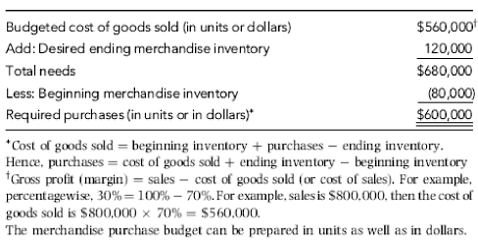

INVENTORY PURCHASES, MERCHANDISING FIRM

Putnam Company is a manufacturing firm, so it prepares a production budget, as shown in Schedule 2. If the company were a merchandising (retailing or wholesaling) firm, then instead of a production budget, it would develop a merchandise purchase budget showing the amount of goods to be purchased from its suppliers during the period. The merchandise purchases budget is in the same basic format as the production budget, except that it shows goods to be purchased rather than goods to be produced:

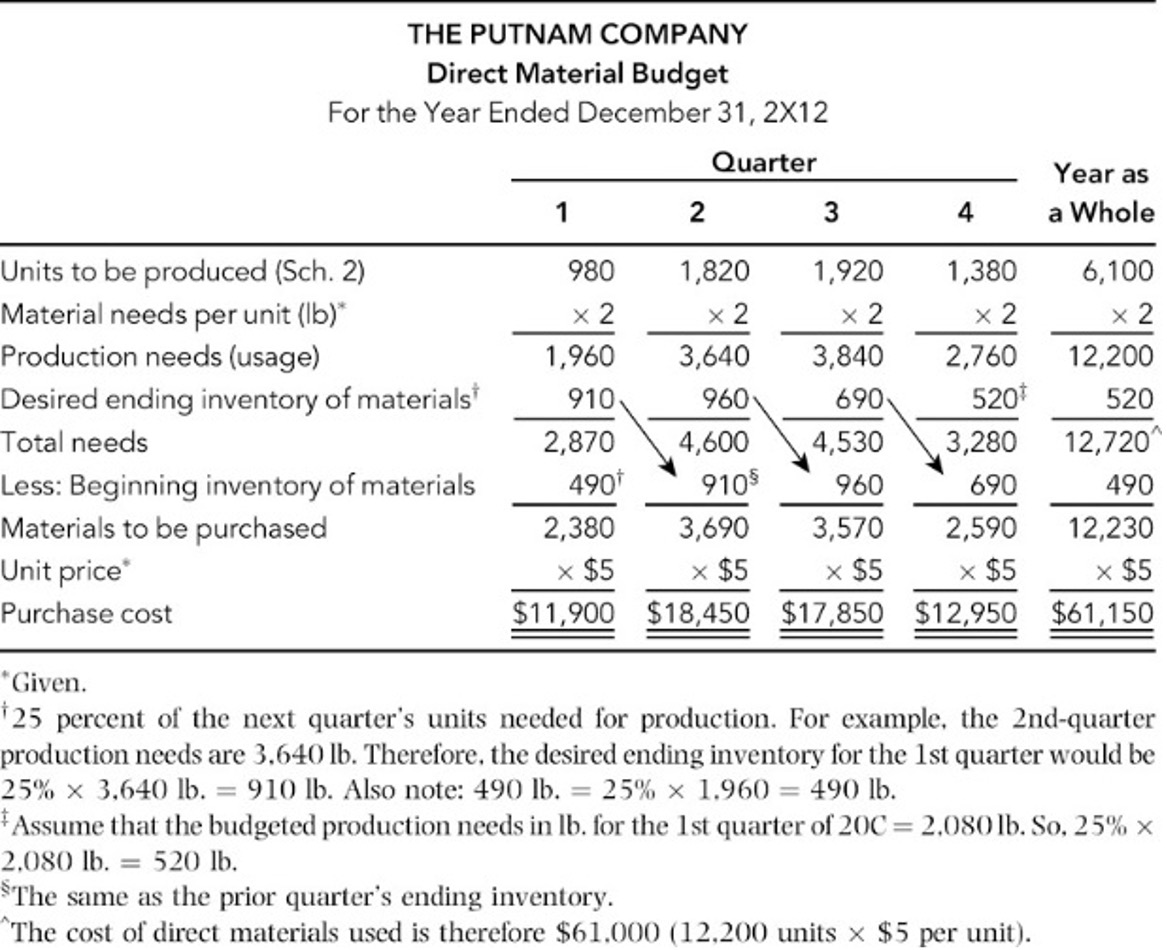

DIRECT MATERIAL BUDGET

When the level of production has been computed, a direct material budget should be constructed to show how much material will be required for production and how much material must be purchased to meet this production requirement. It also tells the cost of direct materials to be purchased, which is needed later for a cash budgeting purpose.

The purchase will depend on both expected use of materials in production and the materials inventory needs of the firm. The formula for computation of the purchase is:

Purchase in units = Direct materials needed for production + Desired material inventory units – Beginning inventory units

The desired ending inventory is determined by the firm's inventory policy. The direct material budget is usually accompanied by a computation of expected cash payments for materials.

Schedule 3

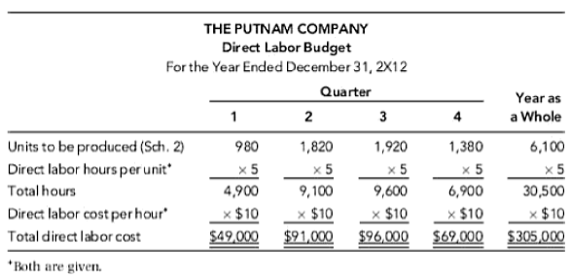

DIRECT LABOR BUDGET

Schedule 4

FACTORY OVERHEAD BUDGET

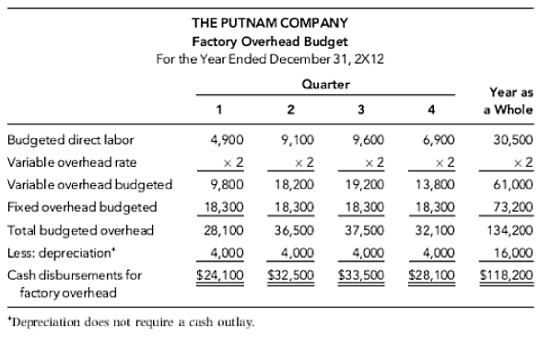

The factory overhead budget should provide a schedule of all manufacturing costs other than direct materials and direct labor, namely, indirect manufacturing costs.

Unlike direct materials and direct labor, there is no readily identifiable input-output relationship for overhead items. Recall, however, factory overhead consists of two types of costs: variable and fixed. Past experience can be used as a guide. To illustrate the factory overhead budget, we will assume that:

- Total factory overhead budgeted = $18,300 fixed (per quarter), plus $2 per hour of direct labor. This is one example of a cost-volume (or flexible budget) formula (Y = a + bX), developed via the least-squares method with a high R2.

- Depreciation expenses are $4,000 each quarter. Note that depreciation does not entail a cash outlay and therefore must be deducted from the total factory overhead in computing cash disbursement for factory overhead.

- Overhead costs involving cash outlays are paid for in the quarter incurred.

Schedule 5

To illustrate the factory overhead budget, we will assume that:

- Total factory overhead budgeted = $18,300 fixed (per quarter), plus $2 per hour of direct labor. This is one example of a cost-volume (or flexible budget) formula (Y = a + bX), developed via the least-squares method with a high R2.

- Depreciation expenses are $4,000 each quarter.

- Overhead costs involving cash outlays are paid for in the quarter incurred.

Schedule 5

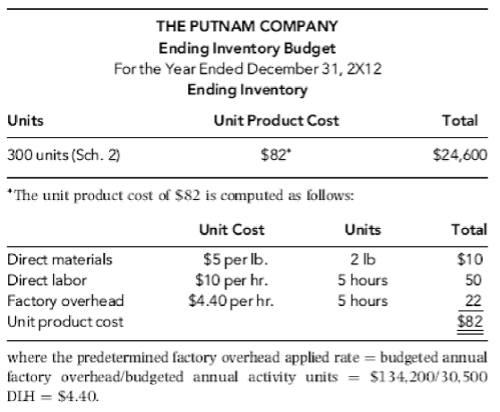

ENDING FINISHED GOODS INVENTORY BUDGET

The ending finished goods inventory budget provides us with the information required for the construction of budgeted financial statements. After completing Schedules 1 through 5, sufficient data will have been generated to compute the per-unit manufacturing cost of finished product. This computation is required for two reasons: (1) to help compute the cost of goods sold on the budgeted income statement and (2) to give the dollar value of the ending finished goods inventory to appear on the budgeted balance sheet. The unit manufacturing cost and the dollar value of the desired ending inventory are shown in Schedule 6.

Schedule 6

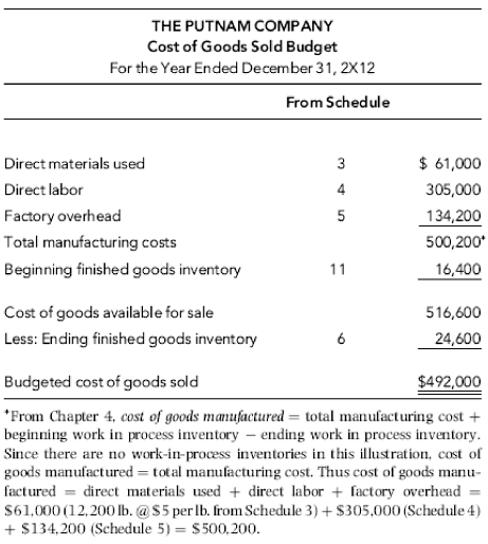

THE COST OF GOODS SOLD BUDGET

Assuming that the beginning finished goods inventory is valued at $26,400 (Schedule 11), the budgeted cost of goods sold schedule can be prepared using Schedules 3, 4, 5, and 6. The cost of goods sold schedule (Schedule 7) will be used as an input for the budgeted income statement.

Schedule 7

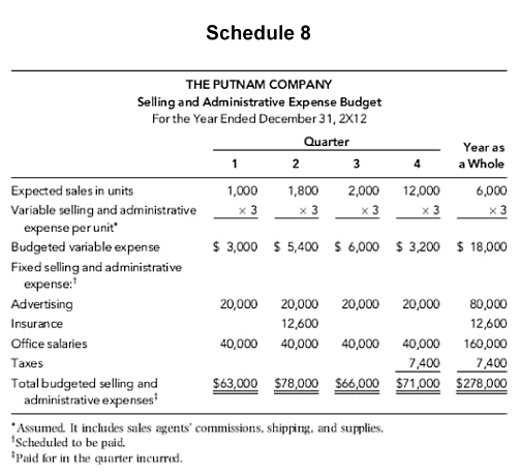

SELLING AND ADMINISTRATIVE EXPENSE BUDGET

The selling and administrative expense budget lists the operating expenses involved in selling the products and in managing the business. Just as in the case of the factory overhead budget, selling and administrative expenses can be broken down into variable and fixed components. Such items as sales commissions, freight, and supplies vary with sales activity. Just as in the case of the factory overhead budget, this budget can be developed using the cost-volume (flexible budget) formula in the form of Y = a + bX. If the number of expense items is very large, separate budgets may be needed for the selling and administrative functions. The selling and administrative expense budget is illustrated in Schedule 8.

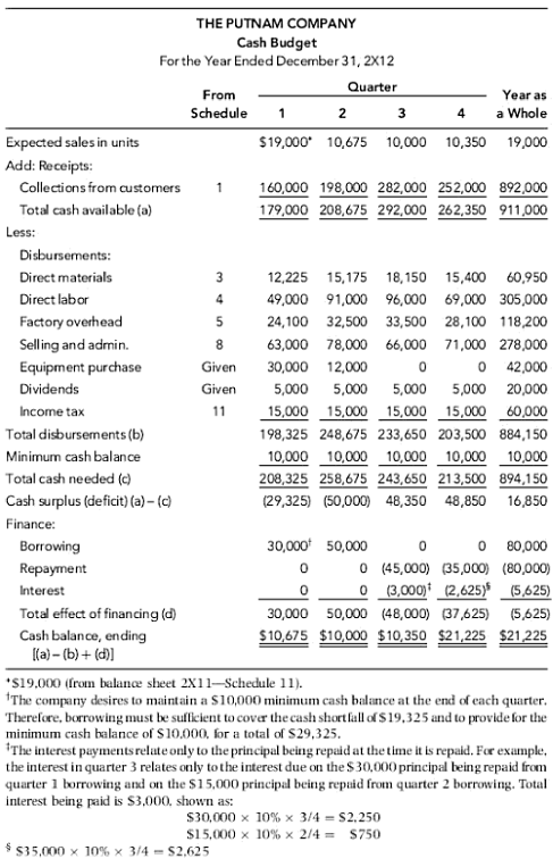

CASH BUDGET

The cash budget is prepared for the purpose of cash planning and control. It presents the expected cash inflow and outflow for a designated time period. The cash budget helps management keep cash balances in reasonable relationship to its needs. It aids in avoiding unnecessary idle cash and possible cash shortages. The cash budget consists typically of five major sections:

- The cash receipts section, which is cash collections from customers and other cash receipts, such as royalty income and investment income.

- The cash disbursements section, which comprises all cash payments made by purpose.

- The cash surplus or deficit section, which simply shows the difference between the total cash available and the total cash needed, including a minimum cash balance if required. If there is surplus cash, loans may be repaid or temporary investments made.

- The financing section, which provides a detailed account of the borrowings, repayments, and interest payments expected during the budgeting period.

- The investments section, which encompasses investment of excess cash and liquidation of investment of surplus cash.

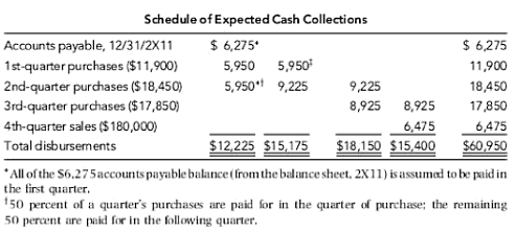

Schedule 9

To illustrate the cash budget, we make these assumptions:

- Putnam Company has an open line of credit with its bank, which can be used as needed to bolster the cash position.

- The company desires to maintain a $10,000 minimum cash balance at the end of each quarter. Therefore, borrowing must be sufficient to cover the cash shortfall and to provide for the minimum cash balance of $10,000.

- All borrowings and repayments must be in multiples of $1,000 amounts, and interest is 10 percent per annum.

- Interest is computed and paid on the principal as the principal is repaid.

- All borrowings take place at the beginning of a quarter, and all repayments are made at the end of a quarter.

- No investment option is allowed in this example. The loan is self-liquidating in the sense that the borrowed money is used to obtain resources that are combined for sale, and the proceeds from sales are used to pay back the loan.

Note

To be useful for cash planning and control, the cash budget must be prepared on a monthly basis.

Also note,

Schedule 9

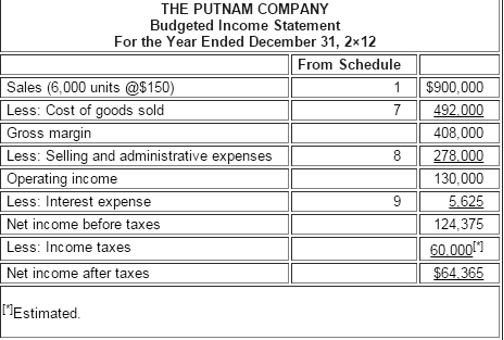

BUDGETED INCOME STATEMENT

The budgeted income statement summarizes the various component projections of revenue and expenses for the budgeting period. However, for control purposes, the budget can be divided into quarters or even months, depending on the need. The budgeted income statement is illustrated in Schedule 10

Schedule 10

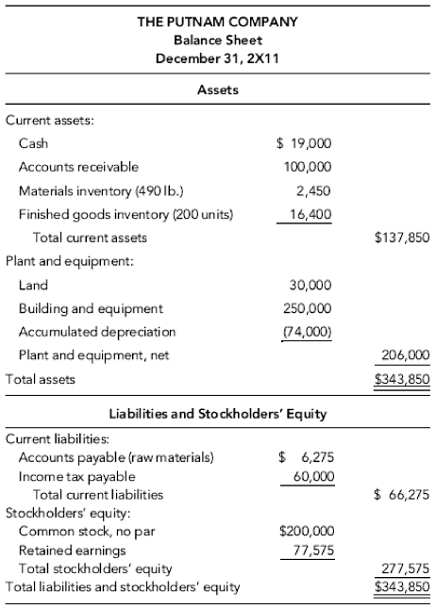

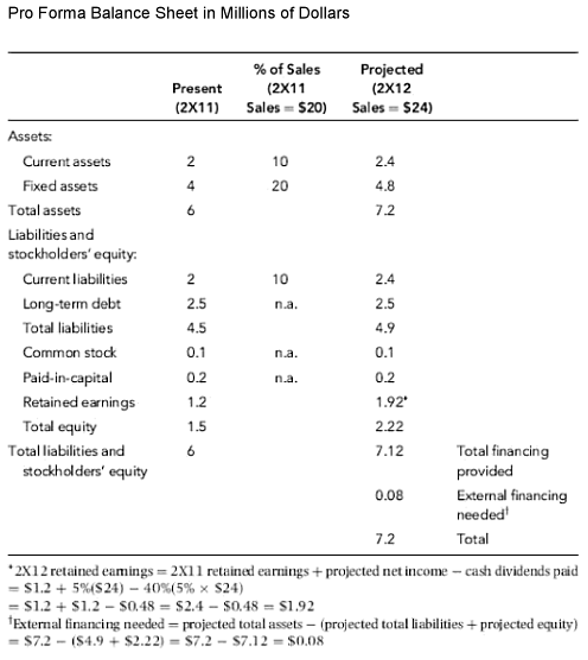

BUDGETED BALANCE SHEET

The budgeted balance sheet is developed by beginning with the balance sheet for the year just ended and adjusting it, using all the activities that are expected to take place during the budgeting period. Some of the reasons the budgeted balance sheet must be prepared are:

- It could disclose some unfavorable financial conditions that management might want to avoid.

- It serves as a final check on the mathematical accuracy of all the other schedules.

- It helps management perform a variety of ratio calculations.

- It highlights future resources and obligations.

We can construct the budgeted balance sheet by using:

- The December 2×11 balance sheet (Schedule 11)

- The cash budget (Schedule 9)

- The budgeted income statement (Schedule 10)

Putnam's budgeted balance sheet for December 31, 2×12, is presented next. Supporting calculations of the individual statement accounts are also provided.

Schedule 11

To illustrate, we will use this balance sheet for the year 2×11.

Schedule 11

SOME FINANCIAL CALCULATIONS

To see what kind of financial condition the Putnam Company is expected to be in for the budgeting year, a sample of financial ratio calculations is in order. (Assume 2×11 after-tax net income was $45,000.)

| Current Ratio | 2X11 | 2X12 |

|---|---|---|

| (Current Assets / Current Liabilities) | $137,850/$66,275 = 2.08 | $156,425/$66,475 = 2.35 |

| Return on Total Assets | ||

| (Net Income after Taxes / Total Assets) | $45,000/$343,850 = 13.08% | $64,375/$388,425 = 16.57% |

Sample calculations indicate that the Putnam Company is expected to have better liquidity as measured by the current ratio. Overall performance will be improved as measured by return on total assets. This could be an indication that the contemplated plan may work out well.

USING AN ELECTRONIC SPREADSHEET TO DEVELOP A BUDGET PLAN

Schedules 1 to 11 showed a detailed procedure for formulating a master budget. In practice, a common shortcut uses computer technology. With a spreadsheet program, managers will be able to develop a master budget and evaluate various what-if scenarios.

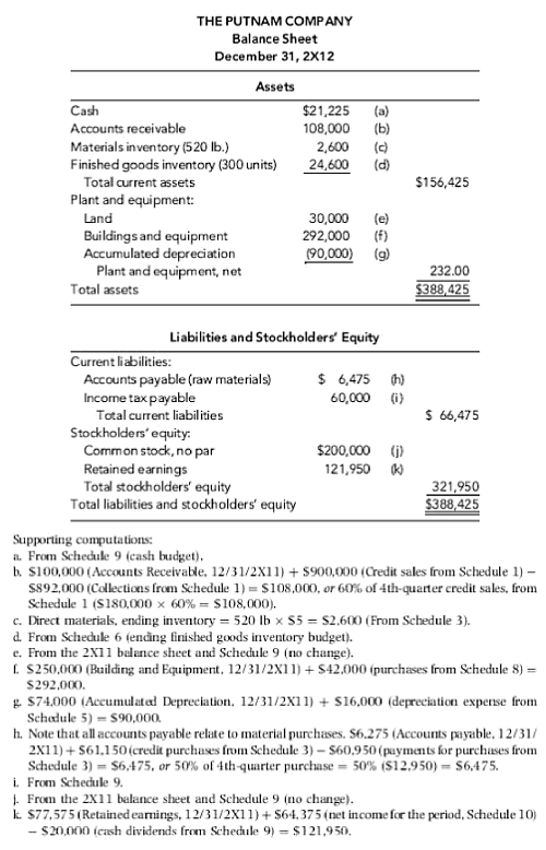

FINANCIAL FORECASTING: THE PERCENT-OF-SALES METHOD

Financial forecasting, an essential element of planning, is the basis for budgeting activities. It is also needed when estimating future financing requirements. The company may look either internally or externally for financing. Internal financing refers to cash flow generated by the company's normal operating activities. External financing refers to capital provided by parties external to the company. You need to analyze how to estimate external financing requirements. Basically, forecasts of future sales and related expenses provide the firm with the information to project future external financing needs.

The four basic steps in projecting financing needs are:

- Project the firm's sales. The sales forecast is the initial most important step. Most other forecasts (budgets) follow the sales forecast.

- Project additional variables such as expenses.

- Estimate the level of investment in current and fixed assets required to support the projected sales.

- Calculate the firm's financing needs.

The most widely used method for projecting the company's financing needs is the percent-of-sales method. This method involves estimating the various expenses, assets, and liabilities for a future period as a percent of the sales forecast and then using these percentages, together with the projected sales, to construct forecasted balance sheets. The following example illustrates how to develop a pro forma balance sheet and determine the amount of external financing needed.

Example 2

Assume that sales for 2×11 = $20, projected sales for 2×12 = $24, net income = 5 percent of sales, and the dividend payout ratio = 40 percent. Schedule 11 illustrates the method, step by step. All dollar amounts are in millions.

The steps for the computations are outlined as follows:

Step 1. Express those balance sheet items that vary directly with sales as a percentage of sales. Any item such as long-term debt that does not vary directly with sales is designated n.a. (not applicable).

Step 2. Multiply these percentages by the 2×12 projected sales = $24 to obtain the projected amounts as shown in the last column.

Step 3. Simply insert figures for long-term debt, common stock, and paid-in-capital from the 2×11 balance sheet.

Step 4. Compute 2×12 retained earnings as shown in (b).

Step 5. Sum the asset accounts, obtaining total projected assets of $7.20, and also add the projected liabilities and equity to obtain $7.12, the total financing provided. Since liabilities and equity must total $7.20, but only $7.12 is projected, we have a shortfall of $0.08 "external financing needed."

The major advantage of the percent-of-sales method of financial forecasting is that it is simple and inexpensive to use. One important assumption behind the use of the method is that the firm is operating at full capacity. This means that the company does not have sufficient productive capacity to absorb a projected increase in sales and thus requires additional investment in assets. Therefore, the method must be used with extreme caution if excess capacity exists in certain asset accounts.

To obtain a more precise projection of the firm's future financing needs, however, the preparation of a cash budget (to be discussed in detail in Chapter 17) is required.

Schedule 12

SUMMARY

Forecasting is an essential element of planning and budgeting. Forecasts of future sales and their related expenses provide managers with information needed to plan other activities of the business.

This chapter has emphasized budgets. The process involves developing a sales forecast and, based on its magnitude, generating those budgets needed by a specific firm. Once developed, the budgeting system provides nonfinancial management with a means of controlling their activities and of monitoring actual performance and comparing it with budget goals.

Budgeting can be done easily with the aid of electronic spreadsheet software. Many specialized application programs are available.

Seven Steps to a Successful Business Plan

Al Coke

AMACOM

New York, NY, 2002

PGS 297 – 304

Contingency Planning: How to Prepare for the Unexpected

Contingency planning is the fifth of the five types of business plans (see Figure 11-1). While it is very important, it is also one of the most neglected elements of a business plan. Because so much energy is put into the basic strategic and operational plans, planning teams seldom give attention to a portion of the total plan that could put a company out of business. This chapter presents two types of contingency planning. The first is long-term, true contingency planning that is designed to counter deviations from your business plans when your assumptions fail. The second is more common and comes quickly to mind. This is disaster planning or crisis management planning, both of which are in vogue with cur-rent business and social trends.

For those planners who would tend to stop reading at this point, let me emphasize again the need to be prepared for the future. No one can predict the future but we can be prepared for it. General Norman Schwarzkopf had this to say about prediction: "The future is not always easy to predict and our record regarding where we will fight future wars is not the best. If someone had asked me on the day I graduated from West Point, in June 1956, where I would fight for my country during my years of service, I'm not sure what I would have said. But I'm damn sure I would not have not said Vietnam, Grenada, and Iraq."' Like all thinking executives, the general didn't sit around unprepared. Over a long and successful career he perfected his skills as a leader, a manager, and a warrior. When the day came for his country to call upon his services he was prepared. His execution of Desert Storm places him in the history books with five-star col-leagues such as "Black Jack" Pershing, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Douglas MacArthur.

Contingency Planning: Preparing for an Unpredictable Future

Contingency planning is being prepared. It is actually that simple. Philip Crosby said it with a little more eloquence: "The centurions will have to learn how to manage so that they can deal with what-ever happens, and at the same time, anticipate what is coming. They will have to be in a permanent situation of awareness in order to tell the difference between fads and reality." One of the earlier strategic planning gurus, George Steiner, also uses a simple but elegant explanation. He defines contingency planning as ". . . preparations to take specific actions when an event or condition not planned for in the formal planning process actually does not take place."' If we listen to Steiner, anything that falls outside the conditions or goals of your strategic and operational plans should be considered a condition for contingency planning.

This business planning model goes one step further. Contingency planning is not outside your planning process. It is a critical component found inside the planning process to position your plan in case of deviation. "The fundamental purpose of contingency planning is to place managers in a better position to deal with unexpected developments than if they had not made such preparations."' Without this preparation managers are always in a reactive mode.

The Five Key Terms Used in Contingency Planning

Early in this chapter we need to sort definitions to ensure we are not talking at cross-purposes with definitions. There are a number of terms to be used when writing about activities that cause deviation from the plan. Some of them and their definitions are: [see table below]

The Two Common Ways That Plans Run Amiss

This business planning cycle and model uses contingency planning as the overall umbrella term to describe what has to be done. The range of contingency situations you'll face can be broken down into two categories, each of which seems to be connected to the time period involved. Trend deviation is connected to the strategic portion of your business plan whereas the crisis element seems to be connected to the tactical or operational plan because of its short-term orientation. A full range of the model is shown in Figure 11-2.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Contingency Planning | The overall activity that looks at the complete situation and plans accordingly. |

| Contingency Plan | The documentation of contingency planning, it is the hard copy of your thinking and intentions. |

| Crisis Management | Actions you take to manage the total environment when facing a disruptive situation. |

| Crisis Intervention | Actions taken to correct a developing situation. As the name implies, there must be an entry into the process of the situation. |

| Disaster Plan | A step-by-step plan of action available for immediate implementation in times of crisis or disaster. |

Trend Deviation: When You Miss the Mark

One type of deviation is experienced when the results of your planning are not developing as you expected. Bluntly speaking, you are missing the mark. You may not be hitting your sale goals because of internal company behavior; maybe management is not performing. Another reason could be due to outside influences. Still a third rea-son is that the market is moving in a different direction from what you assumed, expected, or planned for. In any case your plan is in trouble.

Crises: Circumstances beyond Your Control

A second major type of deviation is the abrupt or sudden disruption of your plan because of circumstances or events usually beyond your control. These crises are usually related to natural disasters and catastrophic events. These situations are usually the ones that come to mind when we think of disruptions and dangers to order and stability.

The Nine Critical Components of a Successful Contingency Plan

Certain considerations are important when facing a deviation from plan over a longer period of time; others become especially important when in a crisis mode. These nine components must be reviewed in a contingency situation no matter what triggered the requirement. In developing your contingency reactions, ask the following questions:

- Facilities. Will you have enough physical support? Are your warehouses and offices located in the right places?

- People. Will you have enough people with the right core competencies to carry on the work? What will be the burnout time for people who must work around the clock?

- Information. Do you have enough facts to make decisions? How risky is it to initiate actions on what information is available? Are you able to get the information you need?

- Time. How fast must you react to the situation before it gets even worse?

- Image. What must you do to protect the public perception of your company during the situation?

- Technology. Can you leverage technology as a replacement for time or people?

- Tools and Equipment. What special tools are needed to carry out your mission? Is any special equipment needed? Where and when will the tools and equipment be needed?

- Leadership and Managership. What leadership and managership behaviors are needed to instil the confidence of the public in your company?

- Assumptions. What assumptions have failed, requiring you to take action? What is the antidote for these best guesses you have made about your business?

The Two Tough Questions for Targeting Potential Problems

When preparing a contingency plan the management team must consider all possibilities and potential target areas, then cut the list down to what is reasonable, realistic, and practical. To start the review, the team asks itself two very hard questions:

- What is the one thing that could put us out of business? Every organization has a weak spot or area of potential danger. Look for the one thing considered the most dangerous to your operation. Account for this happening in your contingency plan. If you work in the software business, a new code or program could put you out of business.

- What is the one thing that could seriously damage our business? There are other events that will not bankrupt you but can nonetheless do enormous damage to your ability to conduct business. Each of these must be accounted for in your contingency planning. Write specific situations and actions for these variations. An example might be when funding for a project is not approved by the board of directors.

A good technique is to conduct a think tank or "blue sky" session to get the management team to examine the problem. A week-end retreat in a nice creative environment would be a way to get the creative juices flowing and out-of-the-box thinking to occur. Think how powerful a two-question agenda could be for the participants.

Coaching For Peak Employee Performance:

A Practical Guide to Supporting Employee Development (2nd ed.)

Bill Foster and Karen R. Seeker

Richard Chang and Associates

San Francisco, CA, 2004

PGS 37 – 43

Overview

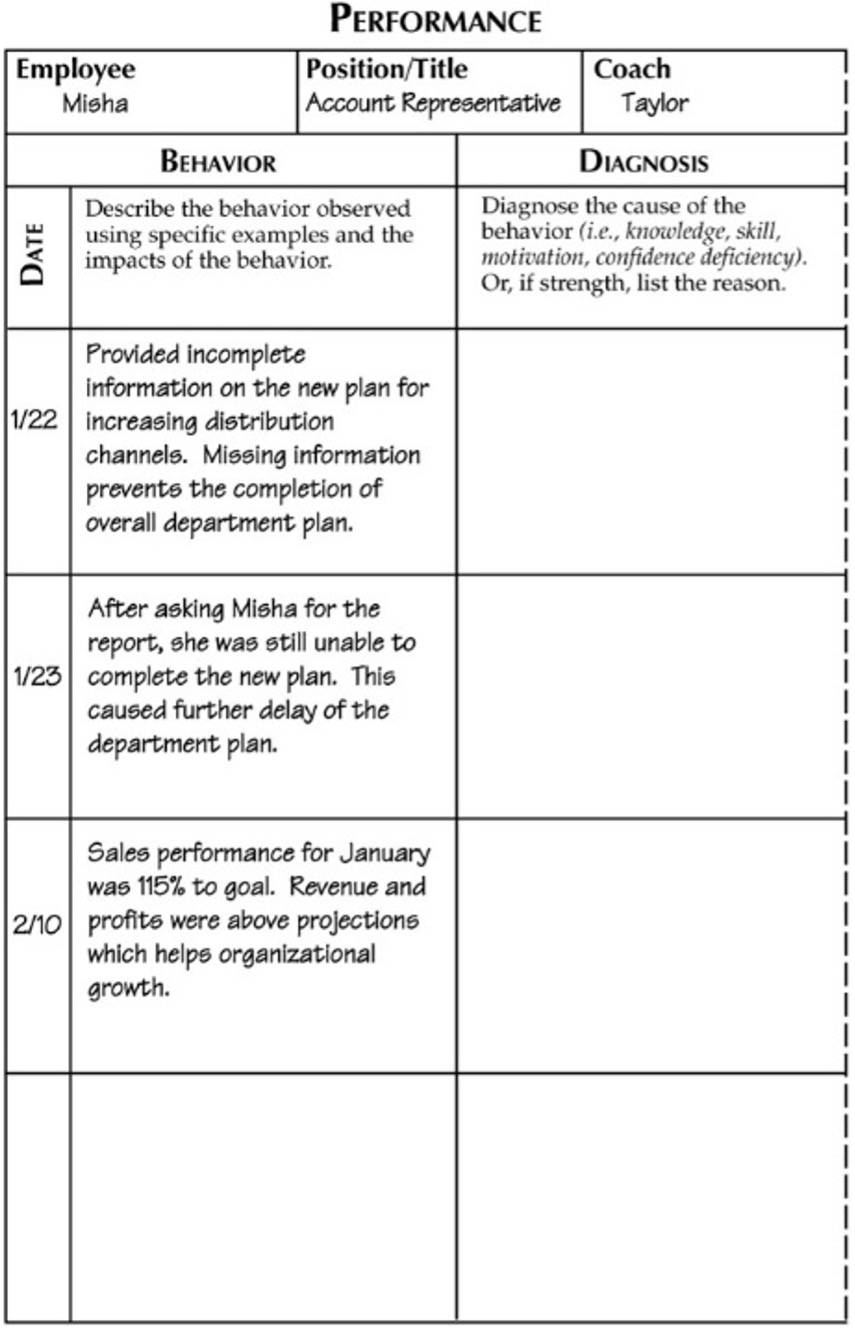

Monitoring your team members' performance is usually the first step in your job as coach. And, it's definitely an important step. You need to observe behaviors before you can diagnose your employees' performance improvement requirements. Think of it in medical terms. Every doctor needs to know a patient's symptoms before she can diagnose an illness.

If you've done your documentation work, you will have documented several specific behaviors for your team members. Those specific behaviors should indicate performance toward their individual objectives. The next questions to ask yourself are:

- Do the behaviors I've listed suggest that this team member can accomplish the performance objective?

- Or, do the behaviors listed suggest that this person needs direction or support from me, the coach?

How you answer determines what you will do next.

Recognizing Behaviors as Deficiencies

If you wish to be an effective coach, you must develop the ability to determine if your employees are demonstrating the capability of achieving their objectives and carrying out their responsibilities. You have to be both observant and insightful. If your team members are struggling, you must be able to provide the appropriate level and type of support they need. Remember, this is the primary function of the coach—to help your team win. You're only as strong as your weakest link.

Before you can offer the appropriate direction or support, you must first understand and diagnose the type of problem each employee is facing. If a team member is not performing as well as needed, any number of reasons may be responsible. For instance, the team member may not:

- Understand how to find the information he needs

- Have the competence to complete the task

- Have access to a complete set of directions

- Want to do the assignment in the way it was designed

- Believe the task is valued in the organization

- Have the ability to complete the assignment

In each of these situations, the reason for the employee not performing differs. Reasons for (or causes of) poor performance are sometimes referred to as "deficiencies." Deficiencies usually tend to fall into one or more of four categories:

- Lack of knowledge

- Lack of skill

- Lack of motivation

- Lack of confidence

In addition, your employees may be restricted by other types of deficiencies which contribute to poor performance, but which cannot be resolved through coaching. Examples include:

- Lack of technology

- Lack of policies/procedures

- Lack of vision/strategic intent of the organization

- Lack of tools

In these instances, you can request additional resources or recommend that upper management provide more guidance. However, in the categories of knowledge, skills, motivation, and confidence, it's up to you to provide specific coaching expertise that will help your team members reach peak performance. It is your job as coach to determine which category best applies and to what extent the employee is demonstrating deficient (or outstanding) behaviors related to the category.

A correct diagnosis is critical. For example, say that you have scheduled one team member to mentor another because you believe that person doesn't understand how to use the computer software. In reality, however, the team member is not producing the document needed because she is being asked by your boss to produce viewgraphs for his speech instead. In this case, your diagnosis is incorrect, and the mentoring time you've scheduled could very well be a waste of time.

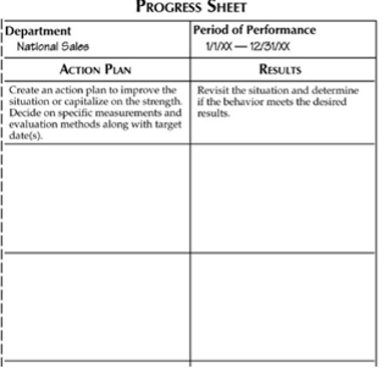

Take a look at the following Performance Progress Sheet that was introduced in the previous chapter [see figure on following page]. If you have completed the monitoring step, you should have documented one or several behaviors by now.