One method of pest control is a sticky trap, like this one.

Integrated pest management (IPM) is an ecosystem-based approach to managing pests that combines a variety of control methods, including cultural, biological, and chemical control, to minimise the impact of pests on crops, human health, and the environment. While the term “pest” is used in the title, in practice, IPM programmes may also include disease identification and control.

Take a stab at putting together the following sentence, which summarises the purpose of IPM. Be sure to click the 'see solution' button before moving on if you are incorrect.

These carrots have been damaged by carrot fly (Chamaepsila rosae). You'll need to make decisions based on the risk factors in your site.

IPM programmes are usually developed for specific crops and growing systems, but they may be designed for the whole growing area. IPM programmes rely on regular monitoring and decision-making based on factors such as pest thresholds, natural enemies, and weather conditions.

Talk to others in your area who grow the same plants and find out the most damaging pests and diseases. Alternatively, research this online. Remember to include “site:nz” in your searches to help make sure you’re looking at information specific to Aotearoa.

Let’s work through an example where we are considering growing carrots and don’t know any other gardeners.

- Online research about your specific plants: We might start by looking on Wikipedia or Shoot Gardening to see what they say are common pests and diseases that affect carrots.

Alternatively we could ask an artificial intelligence (AI) language model, like ChatGPT “What are the most damaging pests and diseases of carrots in New Zealand?”- Whichever approach you take, it’s a good idea to check the responses by copying the names of the pests or diseases and pasting them into a search engine with the words “New Zealand” or “site:.nz.” For instance “Is carrot fly (Chamaepsila rosae) a problem in New Zealand?”

- Whichever approach you take, it’s a good idea to check the responses by copying the names of the pests or diseases and pasting them into a search engine with the words “New Zealand” or “site:.nz.” For instance “Is carrot fly (Chamaepsila rosae) a problem in New Zealand?”

- Discover control measures: For each pest or disease that is said to be highly damaging to the plant, and is found in Aotearoa, learn about how it spreads and research effective ways to control it.

For pests, learn what it looks like in different lifecycle stages and during which stages damage occurs. For example, the Wikipedia page for carrot fly (Chamaepsila rosae) explains that the flies lay their eggs around developing carrots and when these hatch the larvae burrow into the roots.

It suggests the following controls:- Create a barrier around carrot crops at least 60cm tall, or cover the crop with a fine, lightweight mesh, also called a horticultural fleece or floating mesh.

- Plant companion crops that give off a strong odour, such as onions, chives, or garlic.

- Apply beneficial nematodes to the soil, such as Steinernema spp.

- However, when searched online, there don’t appear to be any species available to buy in Aotearoa that would specifically control carrot fly.

You may not immediately notice the pest, but you will likely notice the damage leafroller caterpillars (of the Tortricidae family) do to the leaves, which is less devastating than what it does to fruit.

Now that you know what is likely to be the problem pests and diseases of your crops, you need to be able to identify them.

Pest insects are just that, insects, so we can use some of the tools and sources we’ve already looked to, to help us identify them. We’ve also talked about some of the key identifying features, such as the head, thorax and abdomen, mouthparts, legs and wings.

Insect identification apps and websites

The following apps and websites may prove useful:

- iNaturalist (app and website) – We covered how to use this in Module 5. The process for posting an observation is the same as for animals.

- What is this bug? (shown below) A database developed by Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research which contains over 240 records related to insects in Aotearoa, including photos. Use the search filters on the right side to narrow down the results based on the number of legs it has, lifecycle stage, colour and so on.

- Interesting Insects and other Invertebrates contains information factsheets for over 150 different insects. It is provided by Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research and Rangahau Ahumāra Kai Plant & Food Research.

- For more detailed information the Entomological Society of New Zealand has a list of specific databases, such as one for ants and another for grasshoppers, on its Tools and Resources page. See the section titled Taxon Records, Synopses and Keys.

Disease identification

Sooty moulds, like the one infecting this leaf, form on exposed sap and honeydew (a sugar-rich syrup formed by aphids and scale insects as they feed on sap). The mould doesn’t enter the plant — it covers the leaf surface, blocking the light and reducing photosynthesis, which — as we have learned, is vital for plant growth. Image and text source: Marc Doyle Treework

Disease identification is far more difficult than identifying insects.

Mycologist, Jerry Cooper, recently commented on iNaturalist about the challenges of identifying pathogens. He notes that because the causal agents of disease are so small, its common to try to identify them based on the symptoms on the plant and this can lead to incorrect identification. He goes on to conclude:

Bottom line - identification of plant diseases through photos of symptoms alone is problematic. Get a microscope if you want to identify plant diseases with adequate certainty.

This is a logical statement when it comes to the scientific study of microorganisms, and it highlights the challenges of correct identification of diseases and their causal agents. However, from a practical point of view, gardeners need to make a best guess at what a particular disease or disorder may be, so they can research how best to control it.

We’ll come back to disorders later in this module, but the following websites may be of use when it comes to identifying diseases, however, as noted they may not always lead to the correct diagnosis:

- Kings Plant Doctor: Can be filtered to only show diseases (including disorders).

- Palmers Pest and Disease Control: Take a look at the sections titled Common pests and diseases for vegetables and Common pests and diseases for fruit trees and ornamentals. Read the symptom and cause – there are at least four diseases listed.

- Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture Plant Doctor: An alphabetical listing of questions and answers, most provided by Andrew Maloy, from his Plant Doctor column in the Weekend Gardener. It covers all manner of plant health questions, including pests, diseases and disorders.

- Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) Diseases and Disorders: A UK-based database containing over 130 records about diseases and disorders. If using this as a research tool it is important to check if any disease you’re interested in is found in Aotearoa. You can do this by using Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research’s Biota website.

- Biota is a database of the names and classification of bacteria, fungi, land invertebrates and plants of Aotearoa.

Using the Biota database

If you want to check if a particular disease has been found in Aotearoa, you can use the Biota database.

Let’s see how to do this by using an example of broad beans (Vicia faba).

1. Research the characteristics you can see:

- You’ve found brown spots on the leaves of your broad beans.

- The spots are dark around the edge and lighter in the middle.

- You find a photo online that looks exactly like it. This webpage identifies the problem: broad bean chocolate spot.

There is a problem with your resource. Do you know what it is?

2. Confirm the suspected problem exists in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

The RHS website's focus is UK-based, so you’re not sure if this is truly what your plant has because you don’t know if broad bean chocolate spot is found in Aotearoa.

You copy the scientific name, Botrytis fabae, and go to the Biota website, paste it into the search box and press Enter. You click on the top record. The one that says “Botrytis fabae Sardiña 1929”.

Under the heading Biostatus, it indicates that this is present in New Zealand (under “Occurence” it says “Present” and under “Geo-region” it says “New Zealand”).

You scroll down the page and see under the Descriptions heading the following text: “It is recorded from Auckland, Hastings, and Nelson, where in wet seasons it can cause crop losses.”

So you’ve answered the question: does broad bean chocolate spot occur in Aotearoa? Answer: yes.

3. You can now research ways to control broad bean chocolate spot.

Found something new?

If you think you’ve found something new to Aotearoa, or you think this could be the first time a particular disease has been seen in your part of the country, report it to the Ministry of Primary Industries (MPI). The same goes for pests: Report a pest or disease.

As the old saying goes, “prevention is better than cure.” The same is true when dealing with pests, diseases and weeds in horticulture: prevention is better than control. In other words it's better to stop damage occurring than to take action after it does.

Some simple strategies to help keep them at bay are:

- Focus on plant health: Keep your plants healthy by ensuring they are getting the light, water and nutrients they need, and are protected from frosts, strong winds and salt spray, except where they are tolerant to these conditions. Take care to prevent damage when working with your plants. Damage caused during transplanting, pruning, harvesting, cultivation/weeding can make plants more susceptible to diseases.

- Create an ecosystem that supports healthy plants:

- Grow companion plants: You may grow these to attract allies that help keep pests away, to deter pests through their smell, or be delicious to them so they’ll eat the companion plants rather than your crops.

- Grow healthy soil: Add organic matter to increase soil biology, improve soil structure, increase water retention, and boost the amount of nutrients available to the plants.

- Attract allies: Create an environment for birds and bugs that eat pest insects, perhaps by building bird houses and bug hotels, and grow plants that flower at different times of the year to encourage insect pollinators.

- Plant disease-resistant plants: Where possible, opt for disease-resistant cultivars.

- Cover the ground:

- Tarp new garden beds: When planting out new garden beds, either tarp them for several weeks before planting to kill off the weeds, or

- Cover the ground with cardboard and/or mulch: (shown above). Make holes in the cardboard or pull back the mulch and plant into it. This will help keep weeds down for a few weeks to give the desirable plants a chance to grow without competition. Mulch has the advantage that it retains soil moisture.

- Add compost: Compost has been shown to be highly effective at suppressing plant diseases (Van Zwieten et al., 2007).

- Use row covers: For crops that are likely to be hit by pests, put row covers (horticultural mesh) on crops as soon as you plant them, to keep pests away.

- Make sure you get row covers with the correct size mesh for the pest you’re trying to prevent. If the holes are too large, the insects will still be able to get through.

- Remove covers when pollination is needed.

- Water roots not shoots: Wherever possible, water plants at the roots rather than on the leaves. This will help prevent diseases from growing on most leaves, stems, and fruit.

- Control humidity in greenhouses: If growing in a greenhouse, make use of the ventilation systems provided. This will help reduce the chance of diseases. You may wish to put mesh over the ventilation areas to allow air to move through the greenhouse but not allow pests to enter.

- Prevent frost on flowers and fruit: If frosts occur in your area at a time that could damage your crops – such as when they are flowering or in the process of setting fruit – take action to prevent this. This may involve:

- moving potted plants under cover

- covering plants with horticultural mesh.

- For larger operations, such as commercial orchards and vineyards, this may include:

- using overhead fans or helicopters to circulate air to prevent it settling and forming frost

- running overhead irrigation to keep a constant stream of water or misting on the flowers or fruit so that frost cannot form.

The dreaded, and common, peach leaf curl disease (Taphrina deformans) will make your fruit rot before it ripens.

In integrated pest management (IPM), a control threshold is a point at which pest populations or damage reach a level that requires action to be taken to control them. It is the point at which the economic cost of controlling the pests is less than the cost of the damage they cause.

The control threshold varies depending on the specific pest or disease, crop, and location, as well as the economic value of the crop and the cost of control measures. Generally, the control threshold is determined through monitoring and scouting of the crop to assess pest populations, incidence of disease, and damage levels. Once the threshold is reached, a control strategy is implemented to reduce the pest or disease and prevent further damage to the crop.

Stop and think about it for a moment.

You now know what a control threshold is, and you have learned enough about growing techniques and practices that you may be able to summarise why we would use a control threshold. See if you complete this activity using what you already know about IPM.

What thresholds to use

In small growing operations, a threshold could be: “Control for cabbage white caterpillars when 20 cabbage whites (butterflies or caterpillars) are identified.”

If your IPM programme relies on “allies,” this is particularly true. If there isn’t enough food (pest insects) for your allies, they are unlikely to come to your garden so setting a threshold that is too low can prevent your control measure from working. (That said, it could still be a good idea to get out and hand pick any cabbage white caterpillars before they do too much damage.)

In the home or community garden or a small-scale horticulture operation, it may be more to do with the grower’s philosophy and how that relates to pests and disease, rather than a decision based on economics.

The following quote from the book The naturally bug-free garden: Controlling pest insects without chemicals (P96), by Anna Hess, says:

So you've boosted your beneficials and tried to outwit the bad bugs that remain, but your corn still has an occasional earworm, and your apples are adorned with spots. What can you do?

Eat the produce anyway! In Organic Orcharding, Gene Logsdon suggests that we lower our expectations for homegrown fruit before we resort to spraying. He figures that if a third of his apples are only fit to give to the hogs, that's okay – the fruits will be turned into bacon. Another third might need to be cut up for cooking into applesauce and baking into pies – who doesn't like apple pie? That leaves a third of his crop that is unblemished and beautiful, perfect for storing in a root cellar and nibbling on all winter.

In contrast to Logsdon’s realistic approach to blemishes, most Americans have grown up eating grocery-store produce, all of which was sprayed with something (be it organic or not) to keep pest damage to a minimum. Next, up to 20% of those fruits and vegetables were discarded for cosmetic reasons before the most beautiful specimens made their way to the supermarket.

If you’re comfortable that one third of your harvest may need to go straight into the compost, or be otherwise disposed of, and the other two thirds is edible, but what it looks like varies, great! This might mean that your control threshold is based on the amount of damage that your plants can sustain to remain healthy and still produce a decent crop.

Control thresholds vary based on the plants and the damage they may sustain.

| Although not typically grown as a crop, kawakawa (Piper excelsum) is a good example of a plant that can tolerate significant damage to its leaves without affecting its health. Researchers found that kawakawa – often found with holes in its leaves caused by the kawakawa looper moth (Cleora scriptaria) – can sustain the loss of 90% of its leaf area with very little impact on its health (Fox, 2021). |  |

An educated guess

You’ve already identified the most common and damaging pests and diseases for your main plant species and identified ways to prevent them from showing up in the first place. Now it's time to make a reasonable guess about how much of that pest or disease you’ll tolerate before you start to attack it.

This involves learning about how damaging each is and how quickly it can spread. For instance, we learned in Module 2 that fire blight (Erwinia amylovera) is highly contagious and hugely damaging – able to destroy entire orchards in a single growing season. Your control threshold for this is likely to be “as soon as any instance of fire blight is detected.”

Alternatively, where tomato/potato psyllids (Bactericera cockerelli) have been discovered you might decide not to treat them. Plants damaged by tomato/potato psyllids that carry the Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum bacteria may lead to decreased yield and discolouration of the potato tubers but doesn't make these unsafe to eat. You might decide to try to get rid of the psyllids after the growing season, so that next year’s crop doesn’t suffer the same fate.

You may want to look at the underside of leaves as part of your plant monitoring tasks. This plant has an aphid infestation.

Monitoring begins with knowing what your plants should look like during each season and lifecycle stage. Then it’s simply a case of careful observation on a regular basis.

Each day you work in your garden, start by “doing the rounds.” Take 5-10 minutes to walk around your garden looking carefully at the plants for any signs of pests, pest damage, disease, or disorder (decline in health).

You may find it useful to install traps to catch pest insects. We talk about this later in this module as a control strategy in its own right, but they also serve as a useful monitoring tool. However, the traps are specific to the species of pest insects you want to monitor.

To easily spot small insects, hold a sheet of clean white paper under the leaves of your plants and gently shake the plants. If insects fall down they’ll be much easier to spot and then identify.

Employ the use of natural pest controls and give a hungry ladybug (of the Coccinellidae family) a feed.

As already mentioned, prevention is better than control, but at some point you’ll probably find pests or diseases on your plants. If it's something you’ve developed an IPM plan for, follow the plan. When the threshold is met, take action. If it doesn’t look like one of the pests or diseases you’ve planned for, research it and decide whether or not you need to take action.

There are four main approaches to controlling pests, diseases (and weeds for that matter):

Biological control

Biological control of pests

Biological control of pests involves using natural predators or parasites to control the pest population. Examples include releasing ladybugs to control aphids (as shown above) or using nematodes to control soil-dwelling pests.

All successful long-term methods involve using predatory insects to kill the ones we don’t like.

Remember though that the reason you have a pest problem is because the animals that would normally take care of (kill) the pests find the location inhospitable. So if you plan on bringing allies in, such as predatory insects, you’ll need to make your garden a place they want to live. If not, as soon as you release them in your garden they will leave.

In organic growing, a rule of thumb is that if you see a bug you don’t like, plant more flowers, but there’s a little more to it.

Predatory insects need:

- shelter, and nesting spots

- food of a varied nature, and available at the times of year that you need them (ideally year-round)

- access to water in a form it can easily use.

You might like to also consider building or buying:

| Bug hotels | Build one like this from ThisNZLife,  |

Or this with help from Bunnings: |

|

| Birdhouses or nesting boxes | These structures invite birds to live in your garden.

|

Purchase either of these two kitsets from Kohab: |

|

| Bird feeders | This page by Forest & Bird Te Reo o Te Taiao gives information about the types of foods you should consider if trying to attract native birds (manu). For instance, you might try to attract korimako (bellbird), tauhou (waxeye, silvereye) and tūī by making nectar and fruit to attract them to your garden and hope they stick around to eat the insects. If you have fruit trees growing you might want to net some of these or opt not to attract these species. |

||

This short article by Kath Irvine, from Edible Backyard, gives some pointers on what insects need: A planting plan to entice the beneficial insects.

Calling for backup: Buying predatory insects and microorganisms

If you’re not having any luck attracting the right sort of allies to your garden, don’t despair, it is possible to buy predatory insects and microorganisms.

For instance:

- Plant-parasitic nematodes can be killed by predatory mites.

- Aphids can be controlled by predatory mites, beneficial nematodes, or Aphidius wasps.

- Thrips can be killed by predatory mites, beneficial nematodes, or Orous bugs.

For more information, check out the BioForce website.

Keep working to create an environment that they’ll like to live in, because whether you attract them or buy them, they’ll only stick around if they have what they need.

Biological control of diseases

Biological control of diseases is a process of applying another organism to prevent the causal agent from infecting plants. These organisms are called bioprotectants.

There is some scientific evidence to suggest that foliar application (spraying on leaves) of whey and milk may have beneficial effects on plant health and can be used to prevent plant diseases. For example, they have proven successful when trialled on grapevines, noting milk and whey protein may feed microbes on the grape and leaf surface which then compete for space and may even consume mildew spores.

Using milk or whey foliar sprays to prevent fungal diseases from occurring is a type of physical control.

▶The permaculture orchard (optional)

Using physical control methods

Watch Stefan talk about three different approaches to controlling pests and diseases in the orchard.

- Significantly decreasing the presence of fungal diseases by spraying the plants with whey foliar spray

- Controlling insect pests using sticky traps

- Controlling other insect pests using bottle traps.

| Heading | Physical control methods |

| Timestamp | 1:45:50 - 1:50:25 |

Cultural control

MoneyMaker variety of tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum) are known to be reliable and disease resistant, making them an ideal crop for cultural control.

Cultural control involves changing the environment to make it less favourable to the survival of pests, diseases and weeds. Examples include:

- Crop rotation: When growing annuals, don’t plant the same family in the same location the following year. For instance, don’t plant tomatoes in soil that was last used to grow potatoes. This will help prevent passing pests and diseases that attack that family, for example tomato/potato psyllids (Bactericera cockerelli), from one crop to the next.

- Planting pest-resistant varieties of crops: This can help to reduce pest populations and decrease the amount of damage caused by pests.

- Adjusting the timing of planting or harvesting: If cabbage white butterflies are a problem in your area, consider only planting brassicas in autumn, once the peak of the cabbage white population has passed.

- Modifying irrigation and fertilisation practices: This can help to create conditions that are less favourable to pest development and growth. For instance, watering the soil (rather than on the leaves) early in the morning deeply and infrequently keeps humidity down, and moisture and humidity are needed by insects to survive and reproduce.

Source: Tekura School ed., Cultural Control Diagram. Available behind a paywall. [Accessed 2 Aug. 2023]. With gratitude for the diagram, it has been redrawn.

Physical control

Netting is an effective way of keeping insect pests away from your crops. Make sure you choose netting that is fine enough to keep away the pests your research has indicated are active in your environment.

Regarding netting. Using the knowledge you already have, can you think of a problem that would occur with your crop yield if you left fine-mesh netting on your plants year-round? Consider the answer before selecting the (+) sign or label below.

If your crops rely on insects for pollination, you'll need to make sure you remove the nets when the flowers appear — otherwise, your netting will prevent those insects from getting to the flowers.

Physical control involves physically removing or excluding pests or diseases from the area. Examples include the use of traps, nets, barriers, and screens.

Screens, such as wind-break mesh, can prevent wind-blown weed seeds from reaching your garden. Building a frame around garden beds and covering it with chicken wire mesh keeps cats, dogs and birds out.

Another standard control method used in small-scale organic gardens is hand-picking. Hand-picking is what it sounds like. It’s picking insect pests, slugs and snails off plants and other areas of the garden and killing or removing them from the garden. While this sounds time-consuming, in her book The Naturally Bug-Free Garden, Anna Hess explains that it takes her less than 10 minutes a day, at least three days a week, to get rid of problem insects from her acre-plus garden.

She notes that being this efficient relies on careful observation; knowing where the insects are in the garden.

| Removing snails by torchlight is an effective way of helping your plants manage this common pest. |  |

| Using the cabbage white example, you can flick the yellow/white eggs off the bottom side of plant leaves onto the soil and handpick off any cabbage white caterpillars that emerge (the caterpillars themselves are green). |   |

Chemical control

Chemical control involves using pesticides to control the pest population and fungicides to control fungal diseases. Chemical control should be used as a last resort and should be used in combination with other control methods. When using pesticides and fungicides it is important to choose the least toxic option that will still be effective and to always follow all safety precautions.

Pesticides and fungicides may be:

- Certified Organic

- formed from organic compounds

- use synthetic active ingredients.

These are listed in order of preference when low-impact kaupapa (principles) are important.

That said, note an 'organic' tag doesn't mean it is safe to consume or work with.

Harrisons, Pest and Disease Control in FruitSome pesticides [and fungicides] are toxic – both chemical and natural organic [varieties]. Being natural organic doesn’t necessarily make it safe.

WARNING: If you intend to use agrichemical sprays to control pests, diseases, or weeds it’s important that you understand how to transport, mix, apply, and dispose of the agrichemicals.

The New Zealand Agrichemical Education Trust operates Growsafe – a range of training and certification options that cover the legal requirements, and practical skills for agrichemical use.

While there isn’t a requirement to be Growsafe certified to use agrichemicals in your home garden, most employers will require this. Additionally, certain agrichemicals can only be bought and used by a Certified Handler.

Even if you don’t need to be certified, it's really important that you know the basics. Growsafe provides free access to many of their online courses.

You can find these at: https://learn.growsafe.co.nz/

You’ll need to create a user account. Once you’ve done this, we suggest you enrol in the course called Basic: Pre-course learning.

WARNING: As well as knowing how to use the agrichemicals, you’ll need to know how to select the right one(s). In Aotearoa, the Novachem Agrichemical Manual contains information about which agrichemicals to use for pests, diseases, and weeds, and on what plants these can be used.

▶Market Gardener's Toolkit (optional)

Integrated pest management in the organic market garden

Watch this useful summary of the information we’ve covered in this topic so far, using real-life examples from the organic market garden.

| Heading | Chapter 9: Insects |

| Timestamp | 0:56:50 – 1:03:25 |

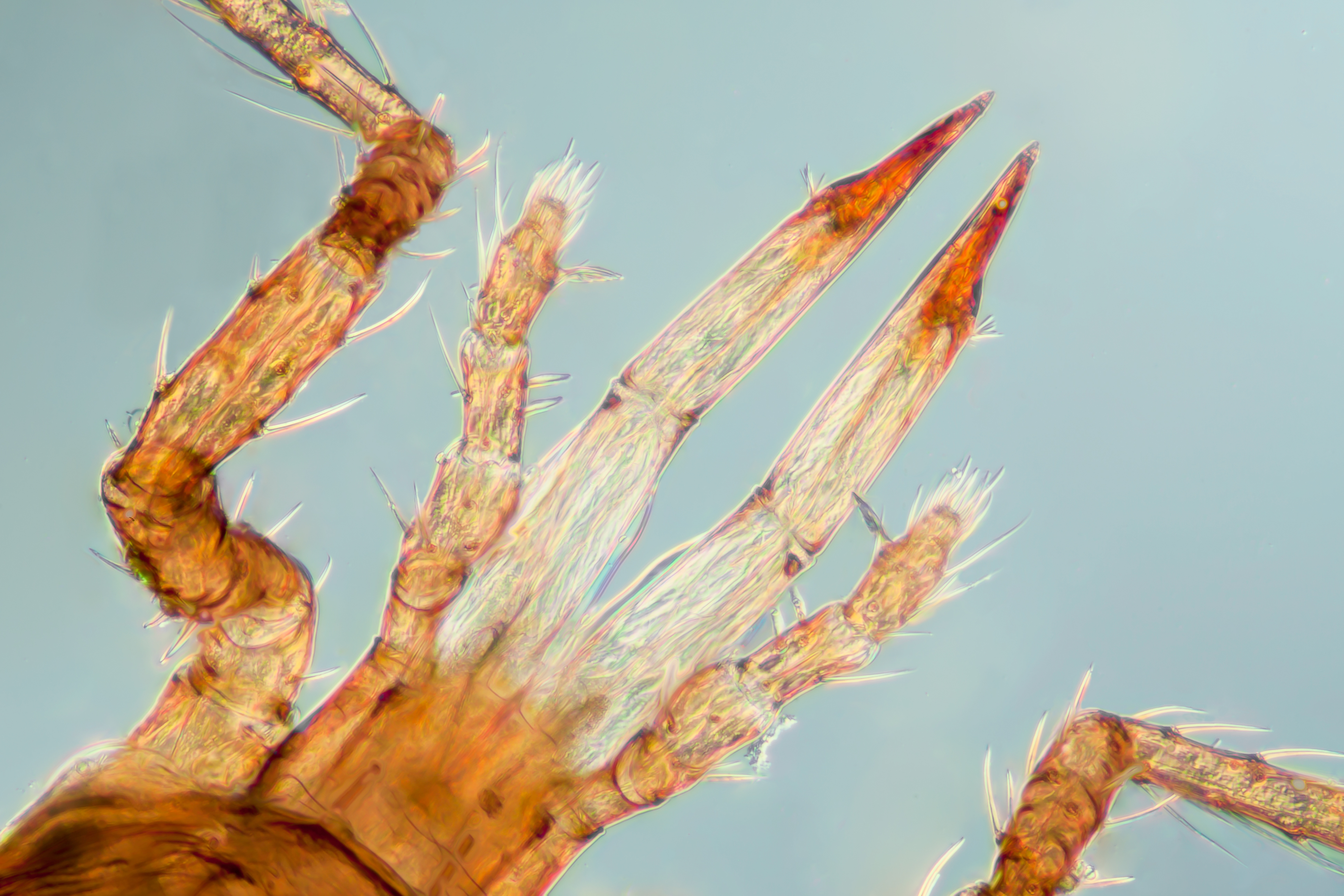

This may look scary, but it's something you may want to introduce to your soil. This is an extreme close-up of the mouthparts of Stratiolaelaps scimitus — a small soil mite that kills other pest insects.

Consumer New Zealand has produced this helpful report about approaches to gardening without insecticides, which provides a good summary of this topic. It also gives some specific examples of prevention and control strategies.

Let’s take a look at some IPM approaches that we may choose to use on a few of the pests and diseases we’re familiar with, based on information searches and conversations with experts. References are provided to show the types of sources that were used to compile this information.

The carrot rust fly adult. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Using a selection of the following IPM control options could be an effective way to control carrot rust fly (Chamaepsila rosae):

- Biological controls

Using natural predators or parasites to control the pest population:- Reference: (personal communication with staff from Bioforce Limited).

- Introduce Hyper-Mite™ (Stratiolaelaps scimitus) a soil-dwelling predatory mite that feeds on carrot rust fly.

- Introduce predatory nematodes: Nemastar (Steinernema carpocapsae) or Nemaplus (Steinernema feltiae).

- Hyper-Mites have been found to be more effective at controlling carrot rust fly, especially those grown over winter, but nematodes offer the benefit of being able to be held in the fridge for several weeks to give growers flexibility around when they release them.

- Reference: (personal communication with staff from Bioforce Limited).

- Cultural controls

Changing the environment to make it less favourable to the pest survival:- Reference: Carrot rust fly.

- “Keep the area free of weeds.”

- “Companion planting can also be effective, so plant onions nearby to help deter adult flies.”

- Reference: RNZIH - Plant Doctor - Carrot rust fly.

- “Rotate crops - don't plant parsnips, carrots, celery or parsley in the same soil year after year. Allow a break of at least one season, preferably two.”

- “Don't leave old, damaged plants of the carrot family in the soil - remove them as soon as practicable. And get rid of any carrot-related weeds like wild carrot, fennel and hemlock.”

- Reference: Gardening without insecticides.

- “Put lawn clippings around the plants – this confuses the flies' sense of smell and stops them landing to lay eggs.”

- “Push earth up around plants to make it harder for larvae to get to the roots.”

- “Thin when plants are small, so you don't damage the roots left in the ground. Flies use their sense of smell to find targets, so disturbing the plants will attract them.”

- “The Egmont Gold variety of carrot tolerates carrot rust fly better than others.”

- Reference: Carrot rust fly.

- Physical controls

Physically removing or excluding pests:- Reference: Gardening without insecticides.

- “Put a polythene "fence" (800mm high) around the crop. This stops flies from finding egg-laying sites near the ground.”

- Reference: Carrot rust fly.

- “Use bug netting to keep adult flies away from crops.”

- “Use bug netting to keep adult flies away from crops.”

- Reference: Gardening without insecticides.

- Chemical controls – using pesticides to control the pest population:

- Reference: RNZIH - Plant Doctor.

- “As a last resort you could apply Diazinon granules to the soil when you sow the carrot seeds, follow the label recommendations.”

- Reference: RNZIH - Plant Doctor.

Using a selection of the following IPM control options could be an effective way to control root mealybugs (Rhizoecus spp.):

- Biological controls

Using natural predators or parasites to control the pest population:- Reference: (personal communication with staff from Bioforce Limited)

- Introduce Hyper-Mite™ (Stratiolaelaps scimitus) a soil-dwelling predatory mite that feeds on root mealybugs amongst other insect pests in soil and growing media.

- Introduce Hyper-Mite™ (Stratiolaelaps scimitus) a soil-dwelling predatory mite that feeds on root mealybugs amongst other insect pests in soil and growing media.

- Reference: (personal communication with staff from Bioforce Limited)

- Cultural controls

Changing the environment to make it less favourable to the pest survival:- Reference: personal communication with knowledgeable grower.

- Grow a greater variety of plants and avoid bulk planting.

- Break up susceptible plants by inter-planting other species.

- Remove the affected plant and soil around it and fully remove or put in a hot compost. This will be enough to kill the bugs assuming they can’t get out.

- Remove surrounding susceptible plants.

- Drench affected crops and soils with a 3% hydrogen peroxide drench or carefully apply a neem oil and horticultural soap blend drench (about 25ml neem, 1 teaspoon of soap and 2 litres of water).

- Reference: Book - The New Zealand Plant Doctor: Answers to your gardening problems, Maloy, A. (2009, p. 42).

- “Root mealybugs tend to prefer open, well-drained soils and don’t like too much moisture, so keeping your vegetable garden well-watered will help deter them.”

- “Cultivating the soil regularly by hoeing, forking and digging will physically damage them and bury them too deep to survive.”

- Reference: personal communication with knowledgeable grower.

- Physical controls

Physically removing or excluding pests:- Reference: personal communication with knowledgeable grower.

- Sterilise nursery equipment so they are not spread by potting mix and pots.

- Sterilise nursery equipment so they are not spread by potting mix and pots.

- Reference: personal communication with knowledgeable grower.

- Chemical controls

Using pesticides to control the pest population:- Reference: RNZIH - Plant Doctor.

- “Treat your garden soil by drenching it with Yates Orthene, which is available from garden centres. Make up the solution in a bucket and pour it over the ground. Leave for 6-12 hours, then drench the affected area with water to wash away any excess Orthene”.

- Reference: Book - The New Zealand Plant Doctor: Answers to your gardening problems, Maloy, A. (2009, p. 42).

- Note that "drenching soil with insecticides is not recommended for vegetable garden soil as there is a risk of contaminating the vegetables (as well damage done to worms and other soil organisms)."

- Reference: RNZIH - Plant Doctor.

King SeedsMarigolds are highly successful in keeping nearby plants healthy by keeping Nematodes under control.

Using a selection of the following IPM control options could be an effective way to control plant-parasitic nematodes:

- Biological controls

Using natural predators or parasites to control microorganisms:- Reference: (personal communication with staff from Bioforce Limited).

- Introduce Hyper-Mite™ (Stratiolaelaps scimitus) a soil-dwelling predatory mite that feeds on plant-parasitic nematodes amongst other insect pests in soil and growing media.

- Introduce Hyper-Mite™ (Stratiolaelaps scimitus) a soil-dwelling predatory mite that feeds on plant-parasitic nematodes amongst other insect pests in soil and growing media.

- Reference: (personal communication with staff from Bioforce Limited).

- Cultural controls

Changing the environment to make it less favourable to the pest's survival:- Reference: Nematode management guidelines.

- Select plants that are less susceptible to nematodes.

- Rotate crops: “Growing a crop on which the nematode pest can’t reproduce is a good way to control some nematodes”.

- Solarise soil: “You can use solarization to temporarily reduce nematode populations in the top [30cm] of soil, which allows the production of shallow-rooted annual crops and helps young woody plants become established before nematode populations increase. However, solarization won’t provide long-term protection for fruit trees, vines, and woody ornamental plants. For effective solarization, moisten the soil, then cover it with a clear, plastic tarp. Leave the tarp in place for 4 to 6 weeks during the hottest part of summer. Root knot nematodes, including eggs, die when soil temperature exceeds [52°C] for 30 minutes or [54°C] for 5 minutes”.

- Reference: personal communication with knowledgeable grower

Remove affected leaves, and if significantly affected, remove affected plants where possible.

- Reference: Nematode management guidelines.

- Physical controls

Physically removing or excluding pests:- Reference: Nematode management guidelines.

- “Nematodes usually are introduced into new areas with infested soil or plants. Prevent nematodes from entering your garden by using only nematode-free plants purchased from reliable nurseries. To prevent the spread of nematodes, avoid moving plants and soil from infested parts of the garden”.

- “Nematodes usually are introduced into new areas with infested soil or plants. Prevent nematodes from entering your garden by using only nematode-free plants purchased from reliable nurseries. To prevent the spread of nematodes, avoid moving plants and soil from infested parts of the garden”.

- Reference: Nematode management guidelines.

- Chemical controls

Using pesticides to control the pest population:- Reference: UGA.edu.

- Nematicides (chemicals that kill nematodes): “Soil fumigants alone or in combination with nonfumigant nematicides can provide vegetable growers effective and reliable control options for plant-parasitic nematodes… but environmental concerns may restrict the broad usage of these products”.

- Reference: UGA.edu.

These branches leaves and pear fruits have been affected by orange rusty spots and horn-shaped growths with spores of the fungus Gymnosporangium sabinae.

RHS.org.ukIn some cases no control is required. For example, many rusts of trees develop too late in the summer to have a significant effect on vigour, even though the whole tree may appear yellow or orange in late summer due to the huge number of rust pustules on the leaves

Where it causes issues to plant health, using a selection of the following IPM control options could be an effective way to control rust:

- Biological controls

Applying another organism to prevent the causal agent from infecting plants- Currently there are none in New Zealand that we could find.

- Currently there are none in New Zealand that we could find.

- Cultural controls

Changing the environment to make it less favourable to the pest survival:- Reference: RHS.org Rust Diseases.

- “Resistant cultivars are available for some plants and crops, but this resistance is occasionally overcome by genetic changes within the rust fungus”.

- “Provide conditions that encourage strong growth but avoid an excess of nitrogen fertiliser as this results in soft, lush growth that is easily colonised by rust”.

- “The best time to water is in the morning, watering into the soil (not onto the plants) as this will help prevent the spread of the spores”.

- Reference: RHS.org Rust Diseases.

- Physical controls

Physically removing or excluding pests:- Reference: RHS.org Rust Diseases.

- “The development of the disease can sometimes be slowed by picking off affected leaves as soon as they are seen, provided that this involves just a small number of leaves. Removing leaves in large numbers is likely to do more harm than good”.

- “Remove all infected plant material from the plant and the ground and dispose of in the rubbish. Don’t put this in your compost as the spores will remain ready to infect again”.

- Reference: RHS.org Rust Diseases.

- Chemical controls

Using pesticides to control the pest population:- Reference: RHS.org Rust Diseases.

- Spray throughout the growing season with a copper spray. Some copper sprays are certified for organic use. “Spraying 4 times a year with a copper spray is often allowed under organic certification”.

- Reference: The New Zealand Plant Doctor: Answers to your gardening problems, Maloy, A. (2009).

- Spray with sulphur “which gives a reasonable control of rust diseases on most plants. Ideally, start spraying early in the season before the disease becomes established”.

- Reference: RHS.org Rust Diseases.

The most effective way to control pests and diseases is to know what to expect and make a plan.

The common starling (Sturnus vulgaris, pictured above) is feasting on ripe fruit, which is not at all desirable. NZ Birds tells us that:

NZ BirdsStarlings are considered both noxious and useful on the New Zealand agricultural scene. Orchardists consider it to be a pest but in pastoral areas, this species is beneficial as it preys upon grass grub (Costelytra zealandica), and other pests.

As the grower, how might you manage that? Where would you start to determine what the risks are to your crops? Would you lean towards drawing the birds in or keeping them away? To answer these questions, you'll want to do some research and then make a plan.

As mentioned in Module 1, if you’re relatively new to gardening, start with a small number of crops, perhaps up to five. This comes in handy when it's time to develop your integrated pest management plan because you only need to develop control strategies for the pests and diseases most likely to attack those plants.

How detailed your plan is will depend on what you’re using it for. If your plan is for a community garden, or commercial growing operation where multiple people are involved, you’ll want the plan to be relatively detailed. If it’s for your home garden, you might keep it quite brief.

Consider covering the following in your plan, to a greater or lesser degree:

- the name of the pest or disease

- when it's most likely to occur

- which lifecycle stage(s) cause the damage (in other words, what to look out for)

- how to monitor for it

- the preventative actions you’ll take

- the control threshold

- what to do once the threshold has been exceeded.

Activity – Planning and resourcing

Refine with experience

Growing plants is an exercise in learning by doing. Don’t worry too much about trying to be right the first time. Instead, keep good records and learn from your experiences. It's a good idea to review and update your IPM plans at the end of each growing season, taking into account what worked well and what didn’t. Use the documents you created above dynamically and keep them updated as you monitor and take action to suppress or remove pests and diseases so you can use them each year to build on.