Reading A: AHANA’s Code of Conduct

Reading B: Allied Health Assistant Framework

Reading C: Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Reading D: A Quick Guide to Australian Discrimination Laws

Reading E: Informed Consent

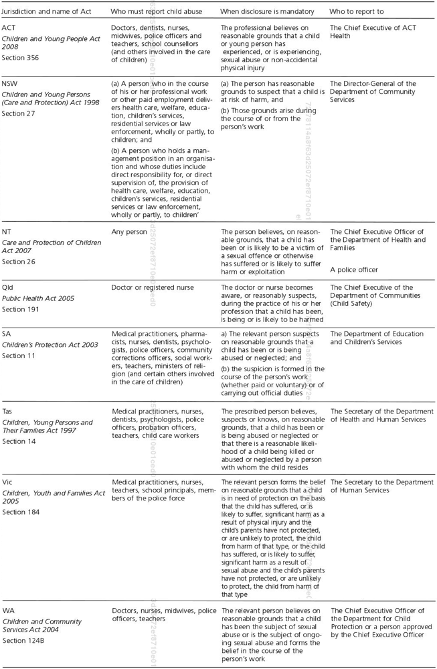

Reading F: Statutory Schemes

Reading G: Mandatory Reporting of Child Abuse and Neglect

Reading H: WHS Code of Practice

Reading I: Ethical Decision-Making in Confidentiality Dilemmas

Reading J: Protections at Work

Important note to students: The Readings contained in these Readings are a collection of extracts from various books, articles and other publications. The Readings have been replicated exactly from their original source, meaning that any errors in the original document will be transferred into these Readings. In addition, if a Reading originates from an American source, it will maintain its American spelling and terminology. IAH is committed to providing you with high quality study materials and trusts that you will find these Readings beneficial and enjoyable.

Allied Health Assistants’ National Association Ltd (AHANA) (2023). Code of Conduct for Allied Health Assistants.

As an Allied Health Assistant, you make a valuable and important contribution to the delivery of high-quality allied health treatment, care and support.

Following the guidance set out in this Code of Conduct (“Code”) will give you the reassurance that you are providing safe and compassionate care of a high standard, and the confidence to challenge or report others who are not. This Code also tells the public and people who use allied health services what they should expect from an Allied Health Assistant in Australia.

As an Allied Health Assistant you must:

- Provide services in a safe and ethical manner, with care and skill, making sure you are accountable and can answer for your actions or omissions.

- Promote and uphold the privacy, dignity, rights, health and wellbeing of people who use allied health services and their carers at all times.

- Work in collaboration with clients, carers and colleagues to ensure the delivery of high quality, safe and compassionate allied health services.

- Communicate in an open and effective way to promote the health, safety and wellbeing of clients and their carers.

- Strive to improve the quality of your practise through continuing professional development and keep your skills and knowledge up to date.

- Uphold and promote equality, diversity, inclusion and cultural safety, and strive to eliminate racism and other forms of discrimination in health and human services.

- Take all reasonable steps to prevent, challenge and report any form of violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation including sexual misconduct and financial exploitation.

Purpose

This Code is designed to protect the public by promoting best practice. Compliance with the Code will ensure that you are ‘working to standard’, providing high quality, compassionate allied health treatment, care and support. The Code describes the standards of conduct, behaviour and atitude that the public and people who use health and care services should expect. You are responsible for and have a duty of care to ensure that your conduct does not fall below the standards detailed in the Code. Nothing that you do, or omit to do, should harm the safety and wellbeing of people who use allied health services, and the public.

Scope

The standards set out in this Code apply to you if you are an AHANA:

- Practising Member; or

- Student Member.

How does the Code help me as an Allied Health Assistant?

The Code provides a set of clear standards, so you can:

- be sure of the standards you are expected to meet;

- know whether you are working to these standards, or if you need to change the way you are working;

- identify areas for continuing professional development; and

- fulfil the requirements of your role, behave correctly and do the right thing at all times.

This is essential to protect the people who use allied health services, the public and others from harm.

How does this Code help people who use allied health services and members of the public?

The Code helps the public and those who use allied health services to understand what standards they can expect of an Allied Health Assistant.

The Code aims to give people who use services provided by Practising Members and Student Members of AHANA the confidence that they will be treated with dignity, respect and compassion at all times.

How does this Code help my employer?

The Code helps employers to understand what standards they should expect of an Allied Health Assistant who is a member of AHANA. If there are people who do not meet these standards, it will help to identify them and their support and training needs.

Glossary

You can find a glossary of terms and key words (shown in bold throughout the Code) at the end of the document.

Acknowledgements

This Code of Conduct is based on and draws extensively from the Skills for Care & Skills for Health Code of Conduct for Healthcare Support Workers and Adult Social Care Workers in England (Skills for Care & Skills for Health, 2013) (the SCSH Code.)

This Code also incorporates provisions and definitions from the following Australian Codes of Conduct:

- National Code of Conduct for Healthcare Workers (COAG, 2015) which applies with some minor modifications in NSW (NSW Health, 2022); Queensland (Queensland Health, 2015), South Australia (SA HSCSS, 2019) and Victoria (Victorian Health, 2016);

- National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) Code of Conduct (NDIS, 2018);

- Victorian Disability Service Safeguards Code of Conduct (Victorian Dept of Health and Human Services, 2018);

- Ahpra and National Boards Code of Conduct. June 2022 (Ahpra, 2022) (the Ahpra Shared Code). These documents are also fully referenced at the end of the Code, following the Glossary.

PRINCIPLE 1: Provide services in a safe and ethical manner, with care and skill, making sure you are accountable and can answer for your actions or omissions

Guidance statements

As an Allied Health Assistant, you must:

- Act ethically, with integrity, honesty and transparency and never behave or present yourself in a way that calls into question your suitability to work as an Allied Health Assistant.

- Deliver services in a way that complies with Commonwealth, State and Territory laws and regulations, and any statutory or other codes of conduct that govern your work (e.g. the National Code of Conduct for Healthcare Workers, as implemented in some States, and other workplace and funding-related codes of conduct).

- Be honest with yourself and others about the services you can safely provide, recognise your abilities and the limitations of your competence and only carry out or delegate those tasks agreed in your job description and for which you are competent.

- Be able to justify and be accountable for your actions or your omissions.

- Ask your supervisor or employer for guidance if you do not feel able or adequately prepared to carry out any aspect of your work, or if you are unsure how to safely and effectively complete a task.

- Establish and maintain clear and appropriate professional boundaries in your relationships with clients, carers and colleagues at all times.

- Tell your supervisor or employer if you have a conflict of interest in relation to a client or their family, or any issues that might affect your ability to do your job competently and safely. If you have a conflict, or do not feel competent or able to carry out a role, you must report this.

- If the circumstances require you to provide services to a person you have or have had a personal relationship with, report the nature of this relationship to your employer or a senior member of the team so that the conflict may be managed in the best interests of the client.

- Work in ways that support government public health messaging and promote the health of the community, through infection prevention and control, health education and where relevant, health screening.

- Adopt standard precautions for the control of infection in the course of providing services. If you have been diagnosed with a medical condition that can be passed on to other people, follow the advice of a suitably trained registered health practitioner on how to modify your practise to avoid passing on the infection.

- Never provide services under the influence of alcohol or unlawful drugs.

- Obtain and follow the advice of suitably trained registered health practitioner if you are taking prescribed medication or have an impairment or disorder that could compromise your ability to do your job safely and competently.

- Never participate in or promote sharp practices such as overservicing, high pressure sales tactics or inducements, or recommending or promoting services or appliances which are unnecessary or not beneficial to your clients.

- Never ask for or accept any loans, gifts, benefits or hospitality from anyone you are supporting or anyone close to them which may be seen to compromise your position.

- Take timely action in relation to any adverse event that occurs when you are providing services, including providing emergency assistance and complying with reporting requirements and post-event review and improvement processes.

- Report any actions or omissions by yourself or colleagues that you reasonably believe may compromise or have compromised the safety, treatment or care of clients. If necessary, use whistleblowing procedures to report any suspected wrongdoing.

PRINCIPLE 2: Promote and uphold the privacy, dignity, rights, health and wellbeing of people who use allied health services and their carers at all times

Guidance statements

As an Allied Health Assistant, you must:

- Always act in the best interests of clients.

- Treat your clients with respect and compassion and in manner that is culturally safe to their needs.

- Always put the needs, goals and aspirations of your clients first, helping them to be in control and to make decisions and choices about their treatment, care and support.

- Work in ways that promote independence and ability to self-care, assisting your clients to exercise their rights and make informed choices.

- Obtain valid consent before providing allied health treatment, care or support.Respect a person’s right to refuse to receive healthcare services, if they have the legal or cognitive capacity to do so, or their carer’s if the person does not

- Maintain the privacy and dignity of clients, their carers and others and treat all information about clients and their carers as confidential.

- Only discuss or disclose information about clients and their carers in accordance with Commonwealth, state and territory privacy laws and your employer’s privacy policies. Seek guidance from a senior member of staff regarding any confidentiality or privacy issues that you are concerned about and discuss issues about disclosure of personal information about the services provided with a senior member of staff, or the team.

- Be alert to any changes that could affect a client’s needs or progress and report your observations in line with your role description and your employer’s policies, procedures or protocols.

- Make sure that your actions or omissions do not harm an individual’s health or wellbeing.You must never abuse, neglect, harm or exploit clients, their carers or your colleagues.

- Take all reasonable steps to prevent or to challenge and report dangerous, abusive, discriminatory, exploitative or racist behaviour or practice.

- Take comments and complaints seriously, respond to them in line with your employer’s (and any other appropriate) complaints management protocol and inform a senior member of the team.

- Fully cooperate with any investigations by management or external funding or regulatory bodies concerning any incident of violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation, or of a complaint.

PRINCIPLE 3: Work in collaboration with clients, carers and colleagues to ensure the delivery of high quality, safe and compassionate allied health services

Guidance statements

As an Allied Health Assistant, you must:

- Understand and value your contribution and the vital part you play in your team.

- Recognise and respect the roles and expertise of your colleagues both in the team and from other agencies and disciplines, and work in partnership with them.

- Work openly and co-operatively with colleagues including those from other disciplines and agencies, and treat them with respect.

- Work openly and co-operatively with clients and their carers and treat them with respect.

- Honour your work commitments, agreements and arrangements and be reliable, dependable and trustworthy.

- Actively encourage the delivery of high-quality allied health treatment, care and support and the wise use of resources.

PRINCIPLE 4: Communicate in an open and effective way to promote the health, safety and wellbeing of clients and their carers

Guidance statements

As an Allied Health Assistant, you must:

- Communicate respectfully with clients and their carers in an open, accurate, straightforward and confidential way, and in a form, language and manner that enables people to understand the information and provide their decisions and preferences. Consider the age, maturity, culture, linguistic backgrounds and intellectual capacity of clients and carers when you do this.

- Communicate effectively and consult with your colleagues as appropriate.

- Explain and discuss the treatment, care or procedure you intend to carry out with your client (and/or their carer) and only continue if you receive a valid consent.

- Maintain clear and accurate records of the services you provide, including of consent.

- Immediately report to a senior member of the team any changes or concerns you have about a client’s condition.

- Recognise both the extent and the limits of your role, qualifications, knowledge and competence when communicating with clients, carers and colleagues.

- Never make inaccurate or unsubstantiated claims in connection with the services you provide or their benefits, including in advertising.

PRINCIPLE 5: Strive to improve the quality of your practise through continuing professional development and keep your skills and knowledge up to date

Guidance statements

As an Allied Health Assistant, you must:

- Ensure you are up to date and compliant with all statutory and mandatory training required for your role, in agreement with your supervisor or employer.

- Participate in continuing professional development to achieve and maintain the competence required for your role.

- Improve the quality and safety of the treatment, care or support you provide with the help of your supervisor (and a mentor if available), in accordance with your role description and your employer’s policies, procedures or protocols.

- Maintain an up-to-date record of your training and development.

- Contribute to the learning and development of others as appropriate.

- Refresh your skills and knowledge, or arrange to work under more close supervision or mentorship if possible, after returning from a long period of leave or absence from practise.

PRINCIPLE 6: Uphold and promote equality, diversity, inclusion and cultural safety, and strive to eliminate racism and other forms of discrimination in health and human services

Guidance statements

As an Allied Health Assistant, you must:

- Respect the individuality and diversity of clients, their carers and your colleagues.Respect their culture, faith, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, sexuality, age and disability status.

- Acknowledge the systemic racism, social, cultural, behavioural and economic factors that impact on the individual and community health of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people, and take steps to ensure your practise is culturally safe and responsive to their needs.

- Never discriminate or condone any discrimination or racism against clients, their carers or your colleagues.

- Promote equal opportunities and inclusion for clients and their carers.

- Report any concerns regarding individual or systemic discrimination or inequitable treatment to a senior member of the care team as soon as possible.

PRINCIPLE 7: Take all reasonable steps to prevent, challenge and report any form of violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation including sexual misconduct and financial exploitation

Guidance statements

As an Allied Health Assistant, you must:

- Never commit, participate in or condone any form of violence, abuse, harassment, neglect or exploitation of a client or their carer.

- Never commit or participate in any form of sexual misconduct or engage in any inappropriate personal relationship with a client.

- Take seriously and report all allegations of abuse made by a client, or their carer.

- Identify and report situations that could lead to violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation of a client.

- Report any incident of violence, exploitation, neglect or abuse of a client to your supervisor and other relevant authorities, including sexual misconduct or inappropriate personal relationships, as quickly as possible.

- Comply with relevant laws and fully cooperate with any investigation or inquiry by management or an external funding or regulatory body in relation to an incident of violence, abuse, neglect or exploitation.

Glossary of terms

ACCOUNTABLE: accountability is to be responsible for the decisions you make and answerable for your actions (SCSH Code: 11).

ADVERSE EVENT: any incident in which harm results to a person receiving health care; it includes an infection, a fall resulting in injury, or problem with medication or a medical device; some adverse events may be preventable (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2018).

ALLIED HEALTH ASSISTANT: An Allied Health Assistant is a healthcare worker who has demonstrated competencies to provide person-centred, evidence-informed therapy and support to individuals and groups, to help protect, restore and maintain optimal function, and promote independence and well-being. An Allied Health Assistant works:

- within a defined scope of practice and in a variety of settings, where they actively foster a safe and inclusive environment; and

- under the delegation and supervision of an Allied Health Professional. The level of supervision may be direct, indirect or remote and is dependent on the Allied Health Assistant’s demonstrated competencies, capabilities and experience (AHANA, 2022). CARERS: see ‘client’.

CLIENT: this Code uses ‘client’ to mean a person receiving allied health services from the Allied Health Assistant and/or their employing organisation; the term ‘client’ includes ‘patients’, ‘participants’, ‘consumers’, ‘service users’ and ‘service recipients’; depending on the context of practice, the term client may also extend to carers (family members, partners, guardians and other people authorised to make decisions for, or represent, the client) and to groups and/or communities as users of allied health services.

COLLABORATION: the action of working with someone to achieve a common goal (SCSH Code: 11).

COMPASSION: descriptions of compassionate care include: dignity and comfort; taking time and patience to listen, explain and communicate; demonstrating empathy, kindness and warmth; care centred around an individual person’s needs, involving people in the decisions about their healthcare, care and support (SCSH Code: 11). Compassionate means done or approached with compassion.

COMPETENCE: the knowledge, skills, attitudes and ability to practise safely and effectively without the need for close supervision (SCSH Code: 11). COMPETENT: having the necessary ability, knowledge, or skill to do something successfully (SCSH Code: 11). Competently means done with the necessary ability, knowledge, or skill to do something successfully. CONFLICT OF INTEREST: includes potential or actual conflict for example, when a worker or a provider is in a position to exploit their own professional or official capacity for personal or corporate benefit (NDIS Code of Conduct: 34).

CONTINUING PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT: this is the way in which a worker continues to learn and develop throughout their careers, keeping their skills and knowledge up to date and ensuring they can work safely and effectively (SCSH Code: 11).

CULTURAL SAFETY: the ongoing critical reflection of a worker’s knowledge, skills, attitudes, practising behaviours and power differentials in delivering safe, accessible and responsive healthcare free of racism; cultural safety is determined by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals, families and communities (adapted from the Ahpra Shared Code: 29). Culturally safe means practise or behaviour which is designed or intended to provide cultural safety.

DIGNITY: covers all aspects of daily life, including respect, privacy, autonomy and self-worth; while dignity may be difficult to define, what is clear is that people know when they have not been treated with dignity and respect. Dignity is about interpersonal behaviours as well as systems and processes (SCSH Code: 11).

DISCRIMINATION: discrimination occurs when a person, or a group of people, is treated less favourably than another person or group because of their background or certain personal characteristics (Ahpra Shared Code: 29); discrimination can be the result of prejudice, misconception and stereotyping. Whether this behaviour is intentional or unintentional does not excuse it. It is the perception of the person discriminated against that is important (SCSH Code: 11). Discriminate means to act unfavourably towards someone or a group of people because of their background or certain personal characteristics.

DIVERSITY: celebrating differences and valuing everyone; diversity encompasses visible and nonvisible individual differences and is about respecting those differences (SCSH Code: 11).

EFFECTIVE: to be successful in producing a desired or intended result (SCSH Code: 11).

EQUALITY: being equal in status, rights, and opportunities (SCSH Code: 11).

EXPLOITATION: every relationship between an Allied Health Assistant and a client is subject to an imbalance of power; an Allied Health Assistant engages in exploitation of a client if they use or rely on this power imbalance for personal gain or to cause harm or embarrassment to the client; exploitation may take many forms(physical, emotional, sexual and financial) and arises even where the benefit is initiated or offered unprompted by the client themselves.

INAPPROPRIATE PERSONAL RELATIONSHIP: means a relationship which crosses professional boundaries or could be viewed as exploitation. INCLUSION: ensuring that people are treated equally and fairly and are included as part of society (SCSH Code: 11).

MENTORSHIP: is a work-based method of training using existing experienced staff to transfer their skills informally or semi-formally to learners (SCSH Code: 11). A mentor is an experienced staff member providing mentorship.

OMISSION: to leave out or exclude, or fail to act when action is indicated or required (SCSH Code: 11).

POLICIES, PROCEDURES, PROTOCOLS: Materials provided to an employee by their employer that set out the expectations, requirements and procedures of the service or work seting; these policies and procedures may be less formally documented among individual employers and the self-employed.

POWER OF ATTORNEY: a legal document that gives a person, or trustee organisation the legal authority to act for another person, to manage their assets and make financial and legal decisions on their behalf.

PRACTISING MEMBER: a member of one of the AHANA classes of practising membership, i.e. Practising Member (Provisional), Practising Member (General) or Practising Member (Provisional).

PROFESSIONAL BOUNDARIES: the clear separation that should exist between professional conduct aimed at meeting the health, support and care needs of clients and your own personal views, feelings and relationships which are not relevant to the therapeutic relationship (adapted from Ahpra Shared Code section 4.9).

PROMOTE: to support or actively encourage (SCSH Code: 11).

RACISM: includes prejudice, discrimination or hatred directed at someone because of their colour, ethnicity or national origin (Ahpra Shared Code: 30).

RACIST BEHAVIOUR: is behaviour which is prejudicial or discriminatory toward or about someone because of their colour, ethnicity or national origin.

REGISTERED HEALTH PRACTITIONER: an individual who is registered under the Health Practitioner National Law Act 2009 (Cth) (as enacted by laws passed in each State and Territory) to practise a regulated health profession, other than as a student. Registered health practitioners are listed in the Register of Practitioners.

RESPECT: to have due regard for someone’s feelings, wishes, or rights (SCSH Code: 11) and to do something respectfully means to do it with respect.

SELF-CARE: this refers to the practices undertaken by people towards maintaining health and wellbeing and managing their own care needs. It has been defined as: “the actions people take for themselves, their children and their families to stay fit and maintain good physical and mental health; meet social and psychological needs; prevent illness or accidents; care for minor ailments and long term conditions; and maintain health and wellbeing after an acute illness or discharge from hospital.” (SCSH Code: 12).

SEXUAL MISCONDUCT: inappropriate behaviour that may include:

- asking the person on a date;

- touching any part of a person’s body in a sexual way;

- touching a person in a way they do not wish to be touched;

- displaying their genitals to the person;

- coercing, by pressuring or tricking, a person to engage in sexual behaviours or acts;

- making sexual or erotic comments to the person – in person or by text message, email or social media message (as well as writen comments, this includes images and audio);

- making sexually suggestive comments or jokes;

- intentionally staring at a person in a way that makes them feel uncomfortable;

- making comments about a person’s sexuality or appearance;

- making requests of a sexual nature, including to remove clothing, for sexually explicit photographs, videos or for sexual activities;

- showing the person pictures or videos of naked people, or people undertaking sexual activities; and

- ignoring or encouraging sexual behaviour between people with disability that is non-consensual or exploitative.

This list does not cover all situations and there may be other activities or behaviours that constitute sexual misconduct (NDIS Code of Conduct: pp. 35-36).

SHARP PRACTICES: business practices that may in a technical sense be legal but are unethical or dishonest (NDIS Code of Conduct: 37).

SYSTEMIC RACISM: is racism at a systemic level rather than an individual level. It occurs where the systems (e.g. societal, political, organisational, structural) in place lead to outcomes which are unfair or harmful to some people and/or provide others unfair advantages, based on their race.

STANDARD PRECAUTIONS: Work practices that constitute the first-line approach to infection prevention and control in the healthcare environment and recommended for the treatment and care of all patients, including hand hygiene, routine environmental cleaning, appropriate handling of waste and handling of linen. See The Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Infection in Healthcare (National Health & Medical Research Council, Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare 2019: 28-96).

TREATMENT, CARE AND SUPPORT: treatment, care and support enables people to develop or regain the skills or abilities to do everyday things like walk, eat, work, cook, play, see friends and access the community; it might include implementing a skill development, rehabilitation or other treatment program developed by one or more Allied Health Professionals, or providing practical information, support and referral to access community services (adapted from the SCSH Code: 12).

UPHOLD: to maintain a custom or practice (SCSH Code: 12).

VALID CONSENT: for consent to be valid, it must be given voluntarily by an appropriately informed person who has the capacity to consent to the intervention in question; this will be the client or patient, the person who uses allied health services or someone with parental responsibility for a person under the age of 18, someone authorised to do so under a Guardianship order or Power of Attorney or someone who has the authority to make treatment decisions as a court appointed person); agreement where the person does not know what the intervention entails is not ‘consent’ (adapted from the SCSH Code: 12).

WELLBEING: a person’s wellbeing may include their sense of hope, confidence, self-esteem, ability to communicate their wants and needs, ability to make contact with other people, ability to show warmth and affection, experience and showing of pleasure or enjoyment (SCSH Code: 12).

WHISTLEBLOWING: whistleblowing is when a worker reports suspected wrongdoing at work. Officially this is called ‘making a disclosure in the public interest’ and may sometimes be referred to as ‘escalating concerns’; you must report things that you feel are not right, are illegal or if anyone at work is neglecting their duties; this includes when someone’s health and safety is in danger; damage to the environment; a criminal offence; that the company is not obeying the law (like not having the right insurance); or covering up wrongdoing (SCSH Code: 12).

References

- AHANA. (2022). Membership by-law. Retrieved from htps://www.ahana.com.au/public/181/files/Governance%20Documentation/Membership% 20By-law%202022-01_4.pdf

- Ahpra. (2022). Code of Conduct. Retrieved from htps://www.ahpra.gov.au/Resources/Code-ofconduct/Shared-Code-of-conduct.aspx

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2018).

- Australia's health. COAG. (2015). A National Code of Conduct for Health care workers. Retrieved from htps://www.health.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/files/collections/factsheets/c/coa g-health-council_communique_national-code-of-conduct-for-health-care-workers.pdf

- NDIS. (2018). Code of Conduct. Retrieved from htps://www.ndiscommission.gov.au/about/ndiscode-conduct NSW Health. (2022). Public Health Regulation. Retrieved from htps://www.health.nsw.gov.au/phact/Pages/code-of-conduct.aspx

- Queensland Health. (2015). The National Code of Conduct for Health Care Workers. Retrieved from htps://www.health.qld.gov.au/system-governance/policies-standards/national-code-ofconduct

- SA HSCSS. (2019). Code of Conduct for Certain Health Care Workers. Retrieved from htps://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/clini cal+resources/education+and+training/system+improvement/unregistered+health+practitio ners#:~:text=Unregistered%20health%20practitioners%20must%20display,Services%20Comp l

- Skills for Care & Skills for Health. (2013). Code of Conduct for Healthcare Support Workers.

- Victorian Dept of Health and Human Services. (2018). Code of conduct for disability support workers. Retrieved from htps://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/code-conduct-disability-service-workers

- Victorian Health. (2016). Victorian Health Complaints Act. Retrieved from htps://hcc.vic.gov.au/providers/general-health-service-providers-code-conduct

Queensland Health Office of the Chief Allied Health Officer Clinical Excellence Queensland. (2022). Allied Health Assistant Framework.

Introduction

Context

Delegating clinical tasks to allied health assistants has been shown to be an effective strategy for the efficient and timely delivery of allied health services. Optimising the allied health workforce for best care and best value A 10-year Strategy 2019-2029 recommends that local and state-wide allied health workforce profiles are informed by healthcare priorities including the optimisation of allied health assistant roles.^1 The Allied Health Assistant Framework (the Framework) was originally developed in November 2015 as a governance document describing the effective employment and use of allied health assistants in the Queensland health workforce. The Framework has been revised in response to feedback received from allied health staff working within the Queensland public health system.

Purpose

The Framework can be used by hospital and health services (HHSs) to:

- support the development, implementation and evaluation of safe and effective delegation and optimise the effective use of the allied health assistant workforce in allied health services.

- assist allied health assistants, allied health professionals and service managers to understand the roles and scope of practice of the allied health assistant health workforce

Defining allied health assistants

An allied health assistant works under the delegation of an allied health professional to assist with therapeutic and program related tasks. Delegation is a defining feature and fundamental to the definition of an allied health assistant role and patient safety. While allied health assistants work within clearly defined parameters, the role is often flexible, involving a mix of direct patient care and indirect support activities. The mix of duties is determined by a range of factors including the model of care, the needs of the professional/s delegating work to the allied health assistant, and the types of services delivered by the allied health team.^2 For information on delegation practice, or how to determine the types of tasks to be undertaken by an allied health assistant, refer to the Delegation Framework Allied Health.

Allied health assistants may work in either a profession-specific (e.g. physiotherapy assistant, pharmacy assistant) or multidisciplinary capacity (e.g. rehabilitation assistant). Allied health assistants may provide support and mentoring to less experienced allied health assistants and may have a role in supervision.

Queensland Health employs allied health assistants in the Clinical Assistant (CA) stream as part of Health Practitioners and Dental Officers (Queensland Health) Award State 2015. Allied Health Assistant Framework - Office of the Chief Allied Health Officer Clinical Excellence Queensland Clinical assistants contribute to the provision of healthcare across the continuum of care by assisting with clinical and non-clinical task. They undertake delegated clinical tasks related to the direct examination and/or treatment of patients within their training, qualifications and competence. For a list of eligible roles refer to Health Practitioners and Dental Officers (Queensland Health) Certified Agreement (No.3) 2019, Schedule 5.

Allied health assistant positions are usually classified as either full scope (CA3) or advanced scope (CA4) level dependent on requirements of the role. There are also a small number of senior/co-ordinator allied health assistant (CA5 level) positions.

Definitions and abbreviations

The following definitions and abbreviations are used specific to allied health assistants and the intent of this framework:

- Clinical Task Instruction (CTI): describe the best practice process for undertaking a delegated or skill shared task. CTIs are used for training and competency assessment, monitoring, and governance of the delegated or skill shared task. CTIs should only be implemented in a local work unit that possesses a delegation or skill sharing framework that includes safety, governance, evaluation and monitoring systems that will support the delegation/skill sharing model in the team or organisation. For further information https://www.health.qld.gov.au/ahwac/html/clintaskinstructions.

- Competency: demonstrated capacity to apply a set of related knowledge, skills and abilities to successfully perform a task or skill needed to satisfy the special demands or requirements of a particular situation.^3

- Delegation: the process by which an allied health professional allocates clinical and health related tasks to an allied health assistant with the appropriate education, knowledge and skills to undertake the tasks. The allied health professional provides the delegation instruction for the task to the allied health assistant, who accepts and then performs the task with appropriate monitoring by the allied health professional and then provides feedback to the delegating allied health professional.

- Monitoring: the process of reviewing a task delegated by an allied health professional to an allied health assistant to ensure set standards or requirements are being met.^4 The focus of monitoring is on the client i.e. clinical safety and quality of care. Monitoring supports best practice by reviewing the delegated task against planned or anticipated outcomes.

- Supervision: is a formal working alliance between an allied health assistant and allied health professional, with the primary intention to ensure alignment of practice capabilities the supervisee.^5 Supervision may involve direct observation, discussions or other strategies to examine and enhance performance as part of learning and development. For the purpose of this framework supervision will primarily be between the allied health assistant and an allied health professional, but there may be a secondary supervision between the allied health assistant and an experienced allied health assistant.

The Framework

The Allied Health Assistant Framework, as described below, comprises of eight components. Key guidelines within each component aim to give a clear and consistent direction for health services employing and working with allied health assistants.

Component 1: Scope of Practice

- Allied health assistants working in the Queensland public health system will have an individual scope of practice that is informed by and reflected in their role description and service/team plans, procedures and related documentation.

- An allied health assistant’s scope of practice includes tasks that the individual has been trained in and is competent to safely perform and that awre within the scope of allied health assistant role.

- The scope of practice of allied health assistants will vary between settings and clinical areas and can change over time to reflect the evolving needs of the health services.

Component 2: Education, skills and competence

- The Certificate IV in Allied Health Assistance has been identified as the qualification best aligned to enable the full scope of practice for allied health assistants.

- Allied health assistants should be encouraged to progress to attainment of the competencies and skill sets requires for/or linked to the role.

- Some roles may have mandatory qualifications and/or skill sets that are determined by the requirements of the position.

Component 3: Governance

- Service managers, allied health professionals and allied health assistants will have a clear understanding of their responsibilities and accountabilities when implementing delegation.

- Operational and professional responsibilities for allied health assistant roles should be reflected within organisational structures and role descriptions for relevant team members.

- Allied health assistants working within the Queensland public health system will have a role description that reflects the role type and setting, organisational and professional structure and links directly to the clinical service and role supports.

Component 4: Delegation

- Service managers, allied health professionals and allied health assistants will have a clear understanding of the process for delegation within the local service setting, including the systems that support delegation and monitoring.

- Delegation practice and the systems and processes that support safe and effective delegation will be integrated into the team’s quality review cycle.

Competent 5: Continuing education and development

- Continuing education and development is important for allied health assistants to maintain and enhance their skills and knowledge.

- It is a shared responsibility between the individual and their employer, aimed at optimising performance and enhancing patient care.

- Continuing education and development is linked to supervision.

Component 6: Supervision

- Supervision will be provided to allied health assistants for the purpose of continuing education and development

- Allied health assistant positions will have one primary supervisor, who is an allied health professional, but an experiences allied health assistant can provide supervision in collaboration with the allied health professional.

- Supervision sessions will be documented.

- Supervision may be provided face-to-face or via telehealth.

Component 7: Integrating allied health assistants into allied health teams

- Delegation is supported by well-developed collaborative practice of a multidisciplinary team.

- Allied health assistants and allied health professionals in the team require orientation to how delegation is implemented and the role of the allied health assistant/s in the local tea.

Competent 8: Evaluation and sustainability

- Evaluation forms an integral part of delegated practice.

- Strategies for sustainability should be implemented to embed allied health assistants in the service team.

United Nations. (n.d.). Universal declaration of human rights. Retrieved June 2, 2023

Preamble

Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world,

Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people,

Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law,

Whereas it is essential to promote the development of friendly relations between nations,

Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom,

Whereas Member States have pledged themselves to achieve, in cooperation with the United Nations, the promotion of universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms,

Whereas a common understanding of these rights and freedoms is of the greatest importance for the full realization of this pledge,

Now, therefore,

The General Assembly,

Proclaims this Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction.

Article 1

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

Article 2

Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or international status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, non-self-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty.

Article 3

Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of person.

Article 4

No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.

Article 5

No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

Article 6

Everyone has the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law.

Article 7

All are equal before the law and are entitled without any discrimination to equal protection of the law. All are entitled to equal protection against any discrimination in violation of this Declaration and against any incitement to such discrimination.

Article 8

Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or by law.

Article 9

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile.

Article 10

Everyone is entitled in full equality to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal, in the determination of his rights and obligations and of any criminal charge against him.

Article 11

- Everyone charged with a penal offence has the right to be presumed innocent until proved guilty according to law in a public trial at which he has had all the guarantees necessary for his defence.

- No one shall be held guilty of any penal offence on account of any act or omission which did not constitute a penal offence, under national or international law, at the time when it was committed. Nor shall a heavier penalty be imposed than the one that was applicable at the time the penal offence was committed.

Article 12

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

Article 13

- Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each State.

- Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.

Article 14

- Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution.

- This right may not be invoked in the case of prosecutions genuinely arising from non-political crimes or from acts contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations.

Article 15

- Everyone has the right to a nationality.

- No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality.

Article 16

- Men and women of full age, without any limitation due to race, nationality or religion, have the right to marry and to found a family. They are entitled to equal rights as to marriage, during marriage and at its dissolution.

- Marriage shall be entered into only with the free and full consent of the intending spouses.

- The family is the natural and fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.

Article 17

- Everyone has the right to own property alone as well as in association with others.

- No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property.

Article 18

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.

Article 19

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

Article 20

- Everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association.

- No one may be compelled to belong to an association.

Article 21

- Everyone has the right to take part in the government of his country, directly or through freely chosen representatives.

- Everyone has the right to equal access to public service in his country.

- The will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.

Article 22

Everyone, as a member of society, has the right to social security and is entitled to realization, through national effort and international co-operation and in accordance with the organization and resources of each State, of the economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for his dignity and the free development of his personality.

Article 23

- Everyone has the right to work, to free choice of employment, to just and favourable conditions of work and to protection against unemployment.

- Everyone, without any discrimination, has the right to equal pay for equal work.

- Everyone who works has the right to just and favourable remuneration ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity, and supplemented, if necessary, by other means of social protection.

- Everyone has the right to form and to join trade unions for the protection of his interests.

Article 24

Everyone has the right to rest and leisure, including reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay.

Article 25

- Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control.

- Motherhood and childhood are entitled to special care and assistance. All children, whether born in or out of wedlock, shall enjoy the same social protection.

Article 26

- Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit.

- Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.

- Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children.

Article 27

- Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits.

- Everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author.

Article 28

Everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized.

Article 29

- Everyone has duties to the community in which alone the free and full development of his personality is possible.

- In the exercise of his rights and freedoms, everyone shall be subject only to such limitations as are determined by law solely for the purpose of securing due recognition and respect for the rights and freedoms of others and of meeting the just requirements of morality, public order and the general welfare in a democratic society.

- These rights and freedoms may in no case be exercised contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations.

Article 30

Nothing in this Declaration may be interpreted as implying for any State, group or person any right to engage in any activity or to perform any act aimed at the destruction of any of the rights and freedoms set forth herein.

Australian Human Rights Commission. (2014.). A quick guide to Australian discrimination laws.

Over the past 30 years the Commonwealth Government and the state and territory governments have introduced laws to help protect people from discrimination and harassment. The following laws operate at a federal level and the Australian Human Rights Commission has statutory responsibilities under them:

- Age Discrimination Act 2004

- Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986

- Disability Discrimination Act 1992

- Racial Discrimination Act 1975

- Sex Discrimination Act 1984.

The following laws operate at a state and territory level, with state and territory equal opportunity and antidiscrimination agencies having statutory responsibilities under them:

- Australian Capital Territory – Discrimination Act 1991

- New South Wales – Anti-Discrimination Act 1977

- Northern Territory – Anti-Discrimination Act 1996

- Queensland – Anti-Discrimination Act 1991

- South Australia – Equal Opportunity Act 1984

- Tasmania – Anti-Discrimination Act 1998

- Victoria – Equal Opportunity Act 2010

- Western Australia – Equal Opportunity Act 1984.

Commonwealth laws and the state/territory laws generally overlap and prohibit the same type of discrimination. As both state/territory laws and Commonwealth laws apply, you must comply with both. Unfortunately, the laws apply in slightly different ways and there are some gaps in the protection that is offered between different states and territories and at a Commonwealth level. To work out your obligations you will need to check the Commonwealth legislation and the state or territory legislation in each state in which you operate.

You will also need to check the exemptions and exceptions in both the Commonwealth and state/territory legislation as an exemption or exception under one Act will not mean you are exempt under the other.

For example, see the attached schedule of coverage.

See the tables below for detailed information on each federal, state and territory Act.

Further information

Australian Human Rights Commission

Level 3, 175 Pitt Street

SYDNEY NSW 2000

GPO Box 5218

SYDNEY NSW 2001

Telephone: (02) 9284 9600

National Information Service: 1300 656 419

TTY: 1800 620 241

Email: infoservice@humanrights.gov.au

Website: www.humanrights.gov.au/employers

These documents provide general information only on the subject matter covered. It is not intended, nor should it be relied on, as a substitute for legal or other professional advice. If required, it is recommended that the reader obtain independent legal advice. The information contained in these documents may be amended from time to time.

Revised November 2014.

Federal Laws

| Legislation and grounds of discrimination | Areas covered |

|---|---|

|

Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 Discrimination on the basis of race, colour, sex, religion, political opinion, national extraction, social origin, age, medical record, criminal record, marital or relationship status, impairment, mental, intellectual or psychiatric disability, physical disability, nationality, sexual orientation, and trade union activity. Also covers discrimination on the basis of the imputation of one of the above grounds. |

Discrimination in employment or occupation. |

|

Age Discrimination Act 2004 Discrimination on the basis of age – protects both younger and older Australians. Also includes discrimination on the basis of age-specific characteristics or characteristics that are generally imputed to a person of a particular age. |

Discrimination in employment, education, access to premises, provision of goods, services and facilities, accommodation, disposal of land, administration of Commonwealth laws and programs, and requests for information. |

|

Disability Discrimination Act 1992 Discrimination on the basis of physical, intellectual, psychiatric, sensory, neurological or learning disability, physical disfigurement, disorder, illness or disease that affects thought processes, perception of reality, emotions or judgement, or results in disturbed behaviour, and presence in body of organisms causing or capable of causing disease or illness (eg, HIV virus). Also covers discrimination involving harassment in employment, education or the provision of goods and services. |

Discrimination in employment, education, access to premises, provision of goods, services and facilities, accommodation, disposal of land, activities of clubs, sport, and administration of Commonwealth laws and programs. |

|

Racial Discrimination Act 1975 Discrimination on the basis of race, colour, descent or national or ethnic origin and in some circumstances, immigrant status. Racial hatred, defined as a public act/s likely to offend, insult, humiliate or intimidate on the basis of race, is also prohibited under this Act unless an exemption applies. |

Discrimination in all areas of public life including employment, provision of goods and services, right to join trade unions, access to places and facilities, land, housing and other accommodation, and advertisements. |

|

Sex Discrimination Act 1984 Discrimination on the basis of sex, marital or relationship status, pregnancy or potential pregnancy, breastfeeding, family responsibilities, sexual orientation, gender identity, and intersex status. Sexual harassment is also prohibited under this Act. |

Discrimination in employment, including discrimination against commission agents and contract workers, partnerships, qualifying bodies, registered organisations, employment agencies, education, provision of goods, services and facilities, accommodation, disposal of land, clubs, administration of Commonwealth laws and programs, and superannuation. |

|

Fair Work Act 2009 Discrimination on the basis of race, colour, sex, sexual orientation, age, physical or mental disability, marital status, family or carer responsibilities, pregnancy, religion, political opinion, national extraction, and social origin. |

Discrimination, via adverse action, in employment including dismissing an employee, not giving an employee legal entitlements such as pay or leave, changing an employee’s job to their disadvantage, treating an employee differently than others, not hiring someone, or offering a potential employee different (and unfair) terms and conditions for the job compared to other employees. |

State and Territory Laws

| Legislation and grounds of discrimination | Areas covered |

|---|---|

|

Australian Capital Territory: Discrimination Act 1991 (ACT) Discrimination on the basis of sex, sexuality, gender identity, relationship status, status as a parent or carer, pregnancy, breastfeeding, race, religious or political conviction, disability, including aid of assistance animal, industrial activity, age, profession, trade, occupation or calling, spent conviction, and association (as a relative or otherwise) with a person who has one of the above attributes. Sexual harassment and vilification on the basis of race, sexuality, gender identity or HIV/AIDS status are also prohibited under this Act. |

Discrimination in employment, including discrimination against commission agents and contract workers, partnerships, professional or trade organisations, qualifying bodies, employment agencies, education, access to premises, provision of goods, services or facilities, accommodation, clubs, and requests for information. |

|

New South Wales: Anti-Discrimination Act 1977 (NSW) Discrimination on the basis of race, including colour, nationality, descent and ethnic, ethno-religious or national origin, sex, including pregnancy and breastfeeding, marital or domestic status, disability, homosexuality, age, transgender status, and carer responsibilities. Sexual harassment and vilification on the basis of race, homosexuality, transgender status or HIV/AIDS status are also prohibited under this Act. |

Discrimination in employment, including discrimination against commission agents and contract workers, partnerships, industrial organisations, qualifying bodies, employment agencies, education, provision of goods and services, accommodation, and registered clubs. |

|

Northern Territory: Anti-Discrimination Act 1996 (NT) Discrimination on the basis of race, sex, sexuality, age, marital status, pregnancy, parenthood, breastfeeding, impairment, trade union or employer association activity, religious belief or activity, irrelevant criminal record, political opinion, affiliation or activity, irrelevant medical record, and association with person with an above attribute. Sexual harassment is also prohibited under this Act. |

Discrimination in education, work, accommodation, provision of goods, services and facilities, clubs, insurance, and superannuation. |

|

Queensland: Anti-Discrimination Act 1991 (QLD) Discrimination on the basis of sex, relationship status, pregnancy, parental status, breastfeeding, race, age, impairment, religious belief or religious activity, political belief or activity, trade union activity, lawful sexual activity, gender identity, sexuality, family responsibilities, and association with or in relation to a person who has any of the above attributes. Sexual harassment and vilification on the basis of race, religion, sexuality or gender identity are also prohibited under this Act. |

Discrimination in work and work-related areas (paid and unpaid), education, provision of goods and services, superannuation and insurance, disposal of land, accommodation; club membership and affairs, administration of state laws and programs, local government, qualifications, industrial, trade, professional or business organisation membership, and existing partnership and in pre-partnership. |

|

South Australia: Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (SA) Discrimination on the basis of sex, breastfeeding, including bottle feeding, chosen gender, sexuality, marital or domestic partnership status, pregnancy, race, age, disability, including aid of assistance animal, association with a child, caring responsibilities, religious appearance or dress, and spouse or partner’s identity. Sexual harassment is also prohibited under this Act. |

Discrimination in employment, partnerships, clubs and associations, qualifying bodies, education, provision of goods and services, accommodation, sale of land, advertising (including employment agencies), conferral of qualifications, and superannuation. |

|

Tasmania: Anti-Discrimination Act 1998 (TAS) Discrimination on the basis of age, breastfeeding, disability, family responsibilities, gender, gender identity, intersex status, industrial activity, irrelevant criminal record, irrelevant medical record, lawful sexual activity, marital status, relationship status, parental status, political activity, political belief or affiliation, pregnancy, race, religious activity, religious belief or affiliation, sexual orientation, and association with a person who has, or is believed to have, any of these attributes. Sexual harassment and the incitement of hatred on the basis of race, disability, sexual orientation, lawful sexual activity, or religious belief, affiliation or activity are also prohibited under this Act. |

Discrimination in employment (paid and unpaid), education and training, provision of facilities, goods and services, accommodation, membership and activities of clubs, administration of any law of the State or any State program, and awards, enterprise agreements and industrial agreements. |

|

Victoria: Equal Opportunity Act 2010 (VIC) Discrimination on the basis of age, breastfeeding, disability, employment activity, gender identity, industrial activity, lawful sexual activity, marital status, parental status or status as a carer, physical features, political belief or activity, pregnancy, race (including colour, nationality, ethnicity and ethnic origin), religious belief or activity, sex, sexual orientation, and personal association with someone who has, or is assumed to have, any of these personal characteristics. Sexual harassment is also prohibited under this Act. Victoria: Racial and Religious Tolerance Act 2001 (VIC) Vilification on the basis of race or religion is prohibited under this Act. |

Discrimination in employment, partnerships, firms, qualifying bodies, industrial organisations, education, provision of goods and services, disposal of land, accommodation (including alteration of accommodation), clubs, sport, and local government. |

|

Western Australia: Equal Opportunity Act 1984 (WA) Discrimination on the basis of sex, sexual orientation (including by association), marital status, pregnancy, breastfeeding, race, religious or political conviction, age (including by association), impairment (including by association), family responsibility or family status, gender history, and publication of relevant details on Fines Enforcement Registrar’s website. Sexual harassment and racial harassment are also prohibited under this Act. Western Australia: Spent Convictions Act 1988 (WA) Discrimination on the basis of having a spent conviction is prohibited under this Act. |

Discrimination in employment, including against applicants, commission agents and contract workers, partnerships, professional or trade organisations, qualifying bodies, employment agencies, application forms, advertisements, education, access to places and vehicles, provision of goods, services and facilities, accommodation, clubs, and land. |

Corey, G., Corey, M., & Callanan, P. (2011.). The client’s right to give informed consent. In Issues and ethics in the helping profession (8th ed.), (pp. 160-162). Cengage Learning.

The first step in protecting the rights of clients is the informed consent document. Informed consent involves the right of clients to be informed about their therapy and make autonomous decisions pertaining to it. Informed consent is a shared decision-making process in which a practitioner provides adequate information so that a potential client can make an informed decision about participating in the professional relationship (Barnett, Wise, et al., 2007). One benefit of informed consent is that it increases the chances that clients will become involved, educated, and willing participants in their therapy. Mental health professionals are required by their ethics codes to disclose to clients the risks, benefits and alternatives to proposed treatment. The intent of an informed consent document is to define boundaries and clarify the nature of the basic counseling relationship between the counselor and the client. Although informed consent has both legal and ethical dimensions, it is best viewed “as an integral aspect of the psychotherapy process that is essential for its success” (Snyder & Barnett, 2006, p. 40). Informed consent for treatment is a powerful clinical, legal, and ethical tool (Wheeler & Bertram, 2008).

Informed consent entails a balance between telling clients too much and telling them too little. Most professionals agree that it is crucial to provide clients with information about the therapeutic relationship, but the manner in which this is done in practice varies considerably among therapists. It is a mistake to overwhelm clients with too much detailed information at once, but it is also a mistake to withhold important information that clients need if they are to make wise choices about their therapy. Studies of practitioners’ informed practices have found considerable variability in the breadth and depth of the informed consent given to clients (Barnett, Wise, et al., 2007).

Professionals have a responsibility to their clients to make reasonable disclosure of all significant facts, the nature of the procedure, and some of the more probable consequences and difficulties. Clients have the right to have treatment explained to them. The process of therapy is not so mysterious that it cannot be explained in a way that clients can comprehend how it works. For instance, most residential addictions treatment programs require that patients accept the existence of a power higher than themselves. This “higher power” is defined by the patient, not by the treatment program. Before patients agree to entering treatment, they have a right to know this requirement. It is important that clients give their consent with understanding. It is the responsibility of professionals to assess the client’s level of understanding and to promote the client’s free choice. Professionals need to avoid subtly coercing clients to cooperate with a therapy program to which they are not freely consenting.

Legal Aspects of Informed Consent

Generally, informed consent requires that the client understands the information presented, gives consent voluntarily, and is competent to give consent to treatment (Barnett, Wise, et al., 2007; Wheeler & Bertram, 2008). Therapists must give clients information in a clear way and check to see that they understand it. Disclosures should be given in plain language in a culturally sensitive manner and must be understandable to clients, including minors and people with impaired cognitive functioning (Goodwin, 2009a). To give valid consent, it is necessary for clients to have adequate information about both the therapy procedures and the possible consequences.

Educating Clients About Informed Consent

A good foundation for a therapeutic alliance is for therapists to employ an educative approach, encouraging clients’ questions about assessment or treatment and offering useful feedback as the treatment process progresses. Here are some questions therapists and clients could address at the outset of the therapeutic relationship:

- What are the goals of the therapeutic endeavour?

- What services will the counselor provide?

- What is expected of the client?

- What are the risks and benefits of therapy?

- What are the qualifications of the provider of services?

- What are the financial considerations?

- To what extent can the duration of therapy be predicted?

- What are the limitations of confidentiality?

- What information about the counselor’s values should be provided in the informed consent document so that clients can choose whether they want to enter a professional relationship with this counselor?

- In what situations does the practitioner have mandatory reporting requirements?

- If the person is referred for an assessment or for therapy from the court or from an employer, who is the client?

A basic part of the informed consent process involves giving clients an opportunity to raise questions and to explore their expectations of counseling. We recommend viewing clients as partners with their therapists in the sense that they are involved as fully as possible in each aspect of their therapy. Practitioners cannot assume that clients clearly understand what they are told initially about the therapeutic process. Furthermore, informed consent is not easily completed within the initial session by asking clients to sign forms. The Canadian Code of Ethics for Psychologists (CPA, 2000) states that informed consent involves a process of reaching an agreement to work collaboratively rather than simply having a consent form signed (Section 1.17).

Informed consent is a collaborative process that helps to establish and enhance the therapeutic relationship (Snyder & Barnett, 2006). The more clients know about how therapy works, including the roles of both client and therapist, the more clients will benefit from the therapeutic experience. Educating clients about the therapeutic process is an ongoing endeavour. Informed consent is not a single event; rather, it is best viewed as a process that continues for the duration of the professional relationship as issues and questions arise (Barnett, Wise, et al., 2007; Barnett & Johnson, 2010; Goodwin, 2009a; Snyder and Barnett, 2006; Wheeler and Bertram, 2008).

The informed consent process is a way of engaging the full participation of the client; it is a means of empowering the client, giving it clinical as well as ethical significance. Especially in the case of clients who have been victimized, issues of power and control can be central in the therapy process. The process of informing clients about therapy increases the chances that the client-therapist relationship will become a collaborative partnership.

Practitioners are ethically bound to offer the best quality of service available, and clients have a right to know that managed care programs, with their focus on constant containment, may have adverse effects on the quality of care available. Clinicians are expected to provide prospective clients with clear information about the benefits to which they are entitled and the limits of treatment.

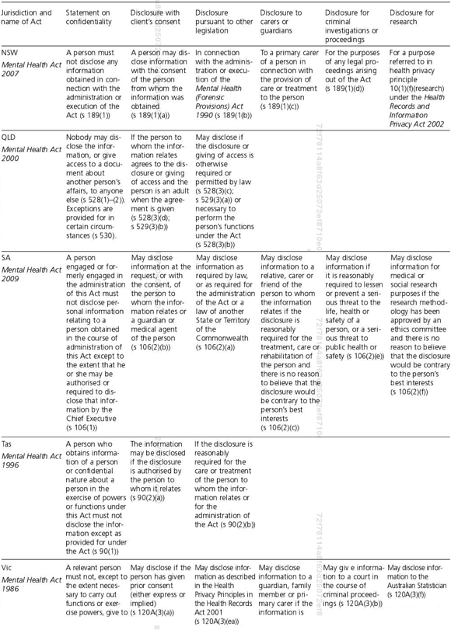

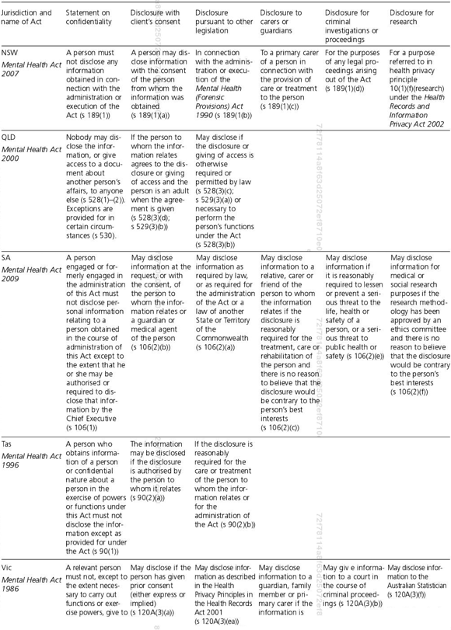

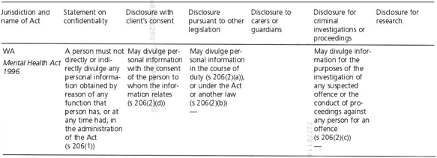

Kampf, A., McSherry, B., Rothschild, A., & Ogloff, J. (2010). Statutory schemes. In Confidentiality for mental health professionals (pp. 75-92). Australian Academic Press.

One of the most complex aspects of the law on confidentiality is trying to understand the variety of legislative provisions dealing with confidential information and its interplay with the common law. It is important to differentiate between the statutory schemes within Commonwealth legislation and the states’ and territories’ legislation that relate to private or confidential information. Confidentiality provisions and provisions for the disclosure of certain information can be found in legislation relating to mental health care; court proceedings; criminal investigations; the use, collection and storage of health information; guardianship; and other areas. The following broad overview of legislative requirements will focus on provisions that specifically address health information or provisions that are particularly relevant to mental health care settings. The overview will include a list of some of the relevant provisions on matters of confidentiality within federal, state and territory legislation. Although this list is not exhaustive, it provides a reference point for understanding the scope of current provisions. If there is some doubt as to which statutory provisions apply to a practical dilemma, it is important and helpful to seek professional advice from indemnity insurers and legal counsel to assist in decision-making.

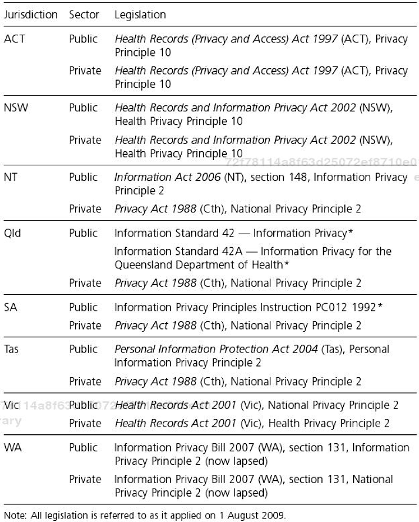

Privacy and Health Records Legislation

The Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) evolved in response to international law developments concerning the protection of privacy. In particular, privacy issues are addressed in:

- the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/ccpr.htm);

- the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Privacy Guidelines (available at http://www.oecd.org/); and

- the Council of Europe’s Convention for the Protection of Individuals with Regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data (http://epic.org/privacy/intl/coeconvention/).

An investigation into Australia’s privacy protection scheme suggested that improvements were necessary in order to comply with international standards (Law Reform Commission, 1983). In response to that finding, privacy legislation was enacted.

The Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) establishes a legal obligation for employees to keep health records confidential. It also distinguishes between two sets of principles: the Information Privacy Principles (IPP) and the National Privacy Principles (NPP). The IPP apply to federal and Australian Capital Territory government agencies, while the NPP apply to parts of the private sector and individuals. The fact that the Privacy Act establishes these two distinctive schemes to handle health information in the private and public sectors can be confusing and has attracted criticism (Office of the Privacy Commissioner, 2005, 64ff).

As the NPP provide specific rules to protect sensitive health information, this type of information is subject to stronger protection than other private information. Principle 2 of the NPP generally prohibits disclosure of personal health information beyond its primary purpose. The primary purpose is typically the diagnosis and treatment of the client or patient. But disclosure is permissible in the following circumstances:

- if it is directly related to the primary purpose and within the client’s or patient’s reasonable expectations;

- if the client or patient consents to it; or

- if disclosure is required or authorised by law.

Sensitive health information may also be disclosed in order to lessen or prevent either a serious and imminent threat to an individual’s life, health or safety, or a serious threat to public health or safety. It should be noted, however, that the NPP do not impose a duty to disclose information. Note 2 in the NPP Schedule 3.2.1 explicitly states that ‘an organisation is always entitled not to disclose personal information in the absence of a legal obligation to disclose it’.