In this section you will learn to:

- Identify, understand, and apply the legal frameworks in AOD practice

- Research and analyse the impacts of various AOD policies and frameworks on AOD practice

- Understand and apply the harm minimisation approach when working with AOD clients

- Understand and apply the ethical and legal considerations when working in AOD context

- Understand how personal values, beliefs, and attitudes may influence your work in the AOD field

Supplementary materials relevant to this section:

- Reading C: National Drug Strategy 2017-2026

- Reading D: The Nature of Addiction: The Strengths Perspective

- Reading E: The Social Determinants in the AOD Context

- Reading F: Australian Community Workers Ethics and Good Practice Guide

- Reading G: Ethics: Cultural Diversity

In the earlier sections of this module, you learned about the different models of why people use alcohol and other drugs for non-medical purposes, as well as why people develop addiction to substances. You also learned about the different drugs that are commonly used in Australia and the harms that they bring upon the individuals who uses AOD and their community.

As a helping professional, in addition to identifying and understanding your client’s substance use, it is also important to understand that different circumstances apply to different clients. In other words, you need to always be aware that there is no one specific intervention that fits every client. Therefore, before learning about the different treatment services for AOD clients, it is important that you thoroughly understand the frameworks that are used when working with AOD clients, and use it to guide you when formulating a treatment approach for your client. You will also need to be aware and consider some of the ethical and legal guidelines during this process.

In this section of the module, you will learn about the general framework used in Australia when working with AOD clients, including the ethical and legal considerations. You will also be introduced to the different services and intervention strategies available to AOD clients.

In the first section of this module, you learned about the different models used to understand the reasons for substance use behaviour and its maintenance. Now you will learn about the frameworks and approaches that are commonly used in Australia to develop the prevention and treatment strategies for AOD clients.

Public Health Model

Similar to the biopsychosocial model you learned earlier, public health model suggests that various factors should be addressed to gain a more comprehensive understanding of an individual’s non-medical drug use. It takes into account that different clients are in different circumstances and had different past experiences. This way, it assists a helping professional to develop appropriate and meaningful treatment approaches.

The public health model was first introduced in Australia in 1985 at the National Drug Summit and serves as a guideline for substance use treatment and prevention programs in Australia (YouthAOD Toolbox, n.d.). The key aspect of this model is that it acknowledges alcohol and other drugs can be both beneficial and hazardous. It also employs a system approach - drug use can occur for various reasons and along a spectrum between abstinence and non-medical drug use. It also emphasises that there are significant differences between different individuals in terms of their susceptibility to drug use, and that social and environmental factors are crucial in determining drug use patterns. On those basis, the public health model suggests that three main factors should be considered when evaluating substance use problem: individual, drug, and environment, see diagram below (adapted from YouthAOD Toolbox, n.d.):

Individual (the characteristic of the individual)

- Age

- Weight

- Mood

- Tolerance to drug or similar dug

- Experience of drug use

Environment (the environment in which drug use occurs)

- Social setting or solo use

- Cultural background

- Prescribed or illegally obtained

Drug (the characteristics of drug or drugs of choice)

- Type of drug

- Route of administration

- Mix of drugs used

- Purity

- Amount

In addition to understanding drug use pattern, these three factors are extremely useful in helping professionals to identify any potential harms that individuals may experience resulting from their drug use. Not only that, but the public health model can also help identify the most suitable interventions when it comes to reducing harm from AOD use (YouthAOD Toolbox, n.d.).

The public health model adopts the goal of harm minimisation, which acknowledges that drug use exists within our community, and it is unrealistic to eliminate it. Hence, the goal of harm minimisation approach is to reduce the harms from drug use. This can be achieved through the following intervention approaches (Department of Health, 2004a; ADF, 2020b):

- Primary prevention: Ensure the problem does not occur in the first place. The strategies aim to shift the focus “upstream” by assisting people to avoid, modify, or reduce drug use instead of reacting to a subsequent “downstream” problem that needs acute treatment.

This can be achieved through community development, drug education, and media-based strategies. For example, encouraging individuals to avoid early or alcohol and other drug use to reduce personal and social dysfunction. This is particularly useful, especially amongst the youths, to prevent future AOD use and its harm. - Secondary prevention: Identify the problem in its early stages and apply intervention to cease further progress of possible problematic drug use.

This can be achieved through screening and identifying risk factors and early warning signs. When potential substance use is detected early and appropriate treatment is administered, it can decrease the risk of the individual developing future AOD-related disorder or illness. - Tertiary prevention: This typically occurs when the harms or impacts identified are considered serious and can affect the different aspects of the individual’s life (e.g., health, finances, and relationships). These strategies focuses on treating existing conditions in an effective manner as well as preventing their reoccurrence. Tertiary prevention strategies also aim to reduce the harms inflicted upon those around the individual who uses drugs (e.g., family and friends, community).

This is usually achieved by treatment approaches such as counselling, pharmacological interventions, hospitalisation, and community-based treatments.

The National Drug Strategy

Since 1985, Australia was committed to adopting harm minimisation approaches as the underpinning principle relating to its national drug policies (i.e., The National Drug Strategy). The National Drug Strategy 2017-2026 (The Strategy) is a decade-long strategy aimed to provide a national framework for the AOD field. It identifies the national priorities relating to alcohol and other drugs, guides the government on partnering with service providers and the community, as well as outlining the national commitment to harm minimisation. The Strategy was developed through a national consultation process that included key informant interviews, online survey feedback, and stakeholder forums. Below is an extract of the Strategy’s aim:

To build safe, healthy and resilient Australian communities through preventing and minimising alcohol, tobacco and other drug-related health, social, cultural and economic harms among individuals, families and communities.

(The National Drug Strategy, 2017-2026, p. 1)

Find Out More

The National Drug Strategy is a national framework that acts as an overarching guide to reduce and prevent harms from drugs use. There are six sub-strategies under the National Drug Strategy and each of them focus on more specific issues and span across different time periods.

Find out more about the sub-strategies here: National Drug Strategy - Sub-strategies.

Harm Minimisation Approach

Based on the Public Health Model, harm minimisation recognises that drug use can occur across a continuum, from occasional or recreational use to dependent use. It also acknowledges that different harms are associated with different types of drugs and drug use patterns, and multifaceted response is needed to respond to these harms. Harm minimisation consists of three pillars: demand reduction, supply reduction, and harm reduction.

The Strategy also emphasises that interventions and strategies employed to prevent and minimise alcohol and other drug use should be evidence-based and balanced across three pillars. The relative impact of strategies based on harm minimisation can vary depending on the type of drugs, differences in legality and regulation, and prevalence of demand and usage behaviours. We will be looking at the three pillars in more details, however, please refer to Reading C to have a more comprehensive understanding of the harm minimisation approach, as well as examples of evidence-based and practice-informed approaches and strategies. This is important because as a helping professional, harm minimisation is the approach that underpins all your work in the sector.

Demand Reduction

Based on the models you learned, no one single factor can solely determine the reason for AOD use. The use can be determined by a range of factors including socialising, coping with stress from work, peer pressure, desire to enhance pleasurable experiences, and more. With that in mind, demand reduction strategies aim to influence these factors in hope to delay, prevent, or reduce the use of drugs. This can be achieved by the following:

- Prevent uptake and delay first use: By preventing the first use of drugs, the strategies will be able to reduce the harms on the individual who uses AOD, their family members, and their community. It will also help to reduce the social costs such as better use of health and law enforcement resources as well as to generate a healthier workforce by reducing drug-related problems at workplace.

Even by delaying first drug use, it can also reduce the longer-term health and social harms from using drugs. For example, the later an individual starts using drug, the lower the risks of harms from drugs, including risk of continued drug use. - Reduce harmful use: The pattern of drug use such as consumption volume, nature of drug and method of administering drugs can lead to harmful consumption of drugs. With effective demand reduction approaches, they can help to mitigate the harms from drugs use.

- Support people to recover from drug-related problems: A wide range of evidence-informed treatment options and support services should be made available and accessible to those who require assistance. For example, from peer-based community support to intensive specialist treatment services in hospital.

Integrated care is also very important - those working with AOD clients need to have a comprehensive understanding of their client’s problems and intervention needs. This includes any potential barriers to recovery such as mental health needs or legal considerations and ensure that the interventions are appropriately addressing the potential diverse needs of their clients.

Further, it is crucial to remember that these strategies need to be able to maintain long-term recovery, as sustainable long-term recovery is strongly associated with quality of life. For example, strategies to enhance social engagement and if needed, reintegration with community. These can be in the form of interventions or programs by social services and community groups working together to enhance accessibility and availability to housing and vocational support etc., to those who require these support.

Examples of demand reduction strategies include establishing price mechanisms for alcohol and tobacco to reduce availability and accessibility to these drugs and regulating restrictions on marketing such as advertising and promotion of alcohol and tobacco.

Supply Reduction

This pillar aims to restrict availability and access to drugs to prevent drug-related problems. Recall that drug experience and its effect can be determined by different factors such as the individual’s age, the method the drug is administered, the setting the drug was taken, etc. Hence, by imposing restrictions on who can use drugs, as well as when, how, and where can they use drugs, it can help to reduce the harm experienced by the individual and their community. In other words, supply reduction approaches prevent and reduce the production and supply of illegal drugs as well as regulate the availability of legitimate drugs. This can be achieved by the following:

- Control licit drug and precursor availability: The harm from legal drugs such as alcohol and tobacco can be reduced by regulating these products’ supply. This can be done by working with the related industry and keep communities informed to prevent substance use. It can also be achieved by enforcing existing regulations and when required, introduce and impose new restrictions or conditions on the use of these licit drugs. Additionally, by regulating the supply for these drugs, it can ensure that they are used legitimately, instead of illicit use.

This includes regulating precursors, which are chemical substances used as ingredients when manufacturing illicit drugs. For example, isosafrole is a precursor used to produce ecstasy; ephedrine is used to manufacture methamphetamine (Pricewaterhouse Coopers, 2016). Therefore, by regulating the supply of isosafrole, the availability of methamphetamine can be regulated as well. - Prevent and reduce illicit drug availability and accessibility: When the supply of illicit drugs, or legal drugs supplied illicitly are disrupted, there will be a reduction of use and in turn, a reduction of consequential harms. Do note that drugs supplied illicitly includes prohibited drugs such as heroin and cocaine, prescribed drugs that are used illicitly, as well as legal drugs that are supplied or manufactured illegally. For example, policing activities aimed at organised crimes or disrupting the distribution networks of illegal drug manufacturing facilities.

Examples of supply reduction strategies include imposing age restrictions to purchase certain drugs such as alcohol and tobacco, and border control of illicit supply of drugs.

Harm Reduction

Strategies based on harm reduction strategies identify specific risks that arise from drug use. Risks from drug use not only impact the individual, but also others around them such as family and friends, as well as the wider community. These strategies encourage safer drug use behaviours, reduce preventable risk factors, and reduce the health and social inequalities among specific populations. This can be achieved through the following:

- Reduce risk behaviours: In addition to the direct harms from drug use, there are also harms from risky behaviours associated with drug use. However, these risky behaviours can be reduced through positive influence from public policy and programs. When individuals perform safer behaviours during drug use, it can reduce harm not only to themselves, but also others around them. For example, laws about smoke-free area was able to reduce people’s exposure to second hand smoke, which in turns reduces the health harms from taking in second hand smoke.

- Safer settings: When a safer environment to use AOD is set up, the positive environmental change can reduce the harmful impacts of drug use. For example, providing access to safe disposal of needles and syringes can help reduce the risk of contracting infectious disease such as blood borne virus from used needles and syringes.

Examples of harm reduction strategies include providing safe transport and sobering up services and setting up “chill out spaces” at music events to provide a quiet and comfortable space for patrons to relax. These spaces can also act as a health information hub to educate patrons regarding substance use at events and how to care for friends who might be using substances (ADF, 2020a).

Even though harm minimisation approach has been guiding our national drug policies for decades, many in the community still have the misunderstanding that adopting this approach is equivalent to condoning drug use. However, this is not the case. We discussed earlier that The Strategy acknowledges drug use (both licit and illicit) exists in our community. Thus, instead of directly ceasing drug use, it is more effective and safer to reduce the harms from drug use through harm minimisation approaches to ensure the safety of our community. Note that these strategies do not necessarily reduce drug use.

To ensure all these strategies are delivered efficiently and have good efficacy in reducing harms from drug use, continual evaluation of these strategies are required. However, this is a complicated process as one strategy may have very different impacts on different population groups and potentially competing interests too. Therefore, it is important for these strategies to be evidence-informed (i.e., based on data and reports to evaluate efficacy of strategies) and sensitive to people from all walks of life and diverse backgrounds.

Read

Reading C: National Drug Strategy 2017-2026

Reading C provides you an understanding of the national framework on reducing the harms from drug use on individuals and their community. It includes the policy context of the development of the Strategy and the underpinning principles that the strategy was based upon.

You will also learn about the national priority areas of focus and how strategies are being implemented to highlight those priorities, as well as the governing bodies who are responsible of regulating and implementing these strategies.

As you complete this reading, reflect on the following questions:

- What are some of the strategies around you that you can identify which attempts to reduce harms from drug use?

- What are some ways that you can improve the strategies when working with your client?

- How can these strategies be implemented in your workplace?

- How can you integrate these guiding principles and priority areas of focus into your work?

Person-Centred Approach

This approach places the “person” (client/patient) at the centre of the treatment or service, and they are always treated as a person first. Your focus should always be on the person themselves and what they can do, and not the problem they are seeking help with or any disability issues that they may have. Your goal as a helping professional should also include supporting and enabling your client to build their life and learning how to exercise control over it. To do so, actively involve your client in decision-making processes such as deciding which intervention to implement or what kind of services they wish to employ; be flexible and patient with the services or support that your clients may require.

As a helping professional, you will need to learn to listen to and understand your client’s needs and place emphasis on what your client wishes to achieve. From there, you will develop an appropriate treatment plan that are specific to your client’s needs and goals post-treatment. For example, you need to take into consideration your client’s age, culture, social support system, beliefs, and any other needs. This is because not all of your clients come from the same background, and they most likely do not share the same experiences as each other (NSW Health, 2020).

Also, it is important that you always remind yourself that your goals for your client may not be the same as the outcome that they wish to achieve. In other words, you need to respect your client’s needs and not impose your personal expectations on them. You will learn more about personal values when working in AOD context in the later part of this Section.

Reflect

Before continuing, take a few minutes to read this factsheet about person-centred approach here: What is a person centred approach? It explains the differences between person-centred and system-centred services and a checklist that outlines the steps to ensure that health professionals are focusing on person-centred outcomes.

Then, read the following case study and consider the steps you would take as a helping professional to ensure that Jason is receiving person-centred care to achieve his desired goals.

Case Study

Jason is a 37 years old male who started consuming alcohol when he was 15 and at a house party with his friends. Over the years, he started to develop tolerance and dependency on alcohol, and even started to experiment with illicit drug use. He also picked up smoking two years ago and smoked an average of 20 cigarettes per day. However, recently, one of his friend passed away from a heroin overdose and Jason decided to seek help to decrease his alcohol intake and illicit drug use. Ultimately, his goal is to lead a drug-free life but admits that he still wishes to maintain his habit of smoking, because he claims that it helps him to sleep better at night.

No Wrong Door Approach

“No wrong door” approach is a guideline whereby no individuals seeking for help should be turned away or refused services. Regardless of which point the individual enter the treatment system, they should all receive adequate and appropriate treatment services. When the facility or provider is unable to deliver a required service or treatment, they should redirect or provide a referral for the individual to the appropriate facility or service provider. This ensures that no one is denied treatment when needed, including individuals who presents more than one condition (i.e., other than substance use problems).

Specifically, in AOD context, a handful of clients seeking for help with substance use problems will present more than one condition and with a dual diagnosis. Therefore, as a helping professional, you need to be prepared for working with clients with comorbid problems and potentially redirecting some individuals to more appropriate treatment or service providers (Department of Health, 2009).

In order to achieve this, treatment and service providers need to work together and have a very high level of coordination and clear communication, especially between AOD and mental health sectors. However, it is also acknowledged that there is a challenge as to which sector of the healthcare system should have the primary responsibility for individual clients with comorbid problems (Comorbidity Guidelines, n.d.). For example, a client may have a comorbid of depression and alcohol use problem – should a helping professional or a psychiatrist take on the primary responsibility of this case? Again, this emphasises the importance of communication between the different treatment providers so that the best treatment plan and approach can be made together with the client.

Guiding Principles of Recovery

Recovery can be defined as “the achievement of an optimal state of personal, social and emotional wellbeing, as defined by each individual, whilst living with or recovering from a mental health issue” (NDIA, 2021). Similar to harm reduction approaches, recovery-oriented approaches aim to improve the quality of life of individuals with substance use problems and want to change that. The difference between recovery-oriented approach and harm reduction approach is that the latter is focused on addressing the need of all individuals who use substance, regardless of whether they wish to change their use or their use does not pose a significant impact, such as recreational use.

As helping professionals, you will mostly be using this framework to work with your client in deciding the goals to be achieved from the treatment plan. This framework will also be underpinning the recovery journey of your client. The guiding principles of recovery are as follows (adapted from Stone et al., 2019):

- Hope: Individuals can and do overcome any challenges or barriers they face and be hopeful that a positive change can occur.

- Person-driven: Individuals are independent and their autonomy should be exercised to the greatest possible extent. Similar to person-centred approach, individuals should be given the control to identify their own goals and decide the treatment and services they wish to pursuit to assist with their recovery goals.

- Many pathways: Acknowledges that people have unique strengths, goals, needs, and backgrounds that influence their recovery needs. Therefore, recovery plans are highly individualised and no two plans are exactly the same. It also acknowledges that setback may occur during the recovery journey and is not a linear process of growth.

- Holistic: All aspects of an individual are included in their recovery – physical, mental, social, emotional, and community. For example, some aspects of an individual’s life to be addressed are employment, self-care, housing, and faith.

- Peer support: Mutual aid and mutual support groups can play a crucial role in an individual’s recovery and should not be neglected. Individuals will be able to share knowledge and skills and have the opportunity for social learning, which fosters a sense of belonging and positive group identity for individuals.

- Relational: One of the important factory in recovery is the presence and involvement of supportive people. The encouragement from supportive people enables the individual to move towards roles which provides greater fulfilment and empowerment.

- Culture: An individual’s values, traditions, and beliefs are crucial to determine their recovery journey. Again, this emphasises the importance of cultural competency when working with clients.

- Addresses trauma: Individuals with a lived experience of substance use typically have trauma history. Therefore, it is important that helping professionals are “trauma-informed” and make sure that they are able to deliver services to clients in a trustworthy and empowering manner. They need to ensure they do not risk re-traumatising vulnerable people.

- Strengths/responsibility: Individuals and their communities have the strengths and resources that can serve as the basis of recovery. Everyone has their own role and responsibility to play in recovery: individuals are responsible to practice self-care and recover; family and friends are responsible to support their loved ones; communities are responsible to provide resources and opportunities to individuals, such as being socially inclusive.

- Respect: Recovery is based on respect. Individuals in recovery are experiencing challenges and difficulties in terms of meeting their recovery goals. It is important that those around them learn to accept individuals do face barriers and try to eliminate discrimination and protect their rights. It is also vital for individuals to learn about self-acceptance and develop a positive and meaningful sense of self.

These ten guiding principles will be the foundation for building a recovery plan with your client. As helping professionals, it is important to always remember that no two clients will have the exact same recovery plan, and recovery means different things to different people. For example, one client may see recovery as being abstinence from alcohol but another may view recovery as building their social support system and establishing his social identity in his community. Therefore, it is extremely vital that you learn to respect and support individualised recovery choices and goals.

Health Promotion

In 1986, the first International Conference on Health Promotion was held in Ottawa, Canada, jointly organised by World Health Organisation, Health and Welfare Canada, and the Canadian Public Health Association. Many health workers, academics and representatives across different organisations globally attended the conference and drew up a charter to reflect their commitment to “Health to All”. The Ottawa Charter was presented in hope to achieve “Health for All” by the year 2000, to ensure that health is seen as a resource for everyday life, not just the objective of living. The three principles below form the foundations of health promotion (World Health Organization, n.d.):

- Advocate: Good health is an important dimension of quality of life. Different factors such as biological, cultural, political, and more can impact health either in a positive or negative way. Health promotions aim to advocate for health and make these factors favourable.

- Enable: Health promotion aims to provide equal opportunities and resources to every individual so they can achieve their fullest health potential. Individuals need to be able to exercise control over decisions that determine their health in order to achieve their fullest health potential.

- Mediate: Achieving health for all cannot be done by the health sector alone and required collaboration across all concerned parties such as governments, non-governmental organisation, the media, and more. Individuals can be involved as families and communities. Health professionals have the responsibility to mediate any differing or competing interests in society for the pursuit of health.

On that basis, in addition to receiving treatment and services related to substance use, helping professionals should also advocate for health promotion to assist individuals in their recovery journey. By enabling and empowering your client to learn to increase their control over making decisions that can improve their own health, it can help their wellbeing and reduce the harms and health risks associated with substance use. For example, you can help your client to acquire the knowledge and skills to make healthy choices such as what healthcare services they need, in addition to services related to substance use. Another example would be assisting your client with comorbid to seek help for their anxiety. Instead of directly referring them to a specific psychiatrist or counsellor, you can provide information of a few mental health professionals and resources about seeking help for anxiety. By assisting your client to obtain these information, you are enabling your client to make an informed decision about improving their mental health.

Empowerment

A key element in health promotion is empowering your client to be actively involved in making their health-related decisions. Empowerment can be defined broadly as the level of choice, influence, and control that individuals can exercise over events in their lives. Similar to what you learned previously, you can empower your clients by ensuring they have sufficient knowledge, skills, and confidence to take control of making decisions in their lives in their recovery. It may seem tough and complicated to “empower” someone, but it can be developed by the following:

- Being non-judgmental and respectful

- Building a relationship and rapport such that your client feels comfortable to discuss their need and feelings

- Focusing on strengths and abilities

- Encouraging your client to be actively involved in decision making

- Respecting the decisions your client makes about their life and recovery

As helping professionals, you have to understand that empowerment is a key process in your client’s recovery. Individuals who seek help with substance use problems may sometimes feel that they have lost control over their life. Therefore, it is crucial that your role includes empowering your client to acknowledge that they can and do play an active role in making decisions related to their life in recovery. These decisions do not only include health-related decisions such as treatment options but also decisions such as employment and housing (NSW Health, 2020).

Not only that, empowerment also includes the intangibles such as feeling confident that they are able to succeed in recovery and that support is available for them when they face any barriers in recovery. You can also empower your client by helping them seek a sense of hope and optimism about the potential opportunities in life post-recovery. For example, you can encourage your client to think about their goals or dreams post-recovery and empower them to work towards it by being optimistic and hopeful that they can achieve it.

Reflect

Before continuing to the next part of this section, take some time to reflect what does the word “empowerment” means to you? Have you felt empowered before and how did that change you?

Are there any specific strategies or ways that you could think of to empower those around you? This can be your clients, your family and friends, or even people in your community.

Read

Reading D: The Nature of Addiction: The Strengths Perspective

Reading D provides an overview of the strengths-based approach which perceives that individuals who are struggling can rise above the challenges and difficulties. It is also considered as one of the dominant approach that is being used in the community work sector, particularly the AOD sector. It also provides an overview of the themes of recovery such as hope and choice.

As you complete this reading, reflect on the following questions:

- Do you think that strengths-based approach is more effective than the traditional approach when working with AOD clients? Why or why not?

- Which theme of recovery do you personally think is the most crucial one in helping AOD clients with their recovery?

- What are your views on the harm minimisation approach and total abstinence approach? Do you prefer one over the other? Why?

Impact of Different Contexts of AOD Sector

The AOD sector is an ever-changing field, and this can be influenced by various factors in different contexts. We will discuss briefly about the impacts of social, political, economic, and legal contexts of AOD sector.

Social Context

There are guidelines put in place that strongly encourage equitable and accessible AOD treatment services to all, however there are still unavoidable barriers and challenges that resulted in the inequitable access to these services. For example, a community centre in a rural area provides a free weekly self-help group program for individuals who wish to reduce alcohol consumption. However, an individual may have language barrier and without an interpreter there, cannot benefit from the service. Therefore, despite the best effort to make treatment services affordable and available, not everyone has the same level of access to them. Further, some in the society hold a more conservative view of AOD use and therefore has more negative views towards individuals who use AOD. As a result, individuals who use AOD may experience stigmatisation and become more apprehensive towards seeking help for AOD use. We will discuss more about stigmatisation in the later part of this section.

Political Context

In order to present more favourably to the people, governments often shape public policies based on the public’s opinion. As a result, some strategies or frameworks developed in the past may not be appropriate for the target population. For example, in recent years, the government has been adopting harm reduction measures to address the increase in AOD use, based on the people’s support of harm reduction measures. This is also reflected in the National Drug Strategy that prioritises harm reduction instead of a zero tolerance policy towards AOD (Matthew-Simmons, 2008).

Economic Context

A huge portion of the AOD sector relies on government’s funding to operate and provide services to individuals who use AOD. However, despite the substantial funding in AOD treatment services, those in the AOD sector often mention that the sector is under-resourced. This is mainly due to the largest portion of government funding for the AOD sector goes into law enforcement, and those in the field suggest that this should be reviewed such that more funding goes towards treatment services to reflect the three pillars of harm minimisation.

Not only that, despite the sector being heavily funded by the respective jurisdictions, there is a high demand for AOD treatment services which results in a long waiting list. This in turn acts as a barrier for individuals who requires AOD treatment and support, and they may continue their AOD use while waiting for appropriate care (Parliament of Australia, 2018).

Legal Context

As you learned earlier, The National Drug Strategy acts as a national guideline in terms of AOD related strategies to help reduce the impact of AOD use and its harm on individuals and their community. There are also different legislations put in place to help regulate the availability of AOD, such as strict border controls to prevent and disrupt the supply of illicit AOD from entering the country (Department of Health, 2017).

Read

Reading E: The Social Determinants in the AOD Context

Reading E provides an overview of the different social determinants that influence an individual’s access to healthcare, particularly access to AOD-related treatment and services.

As you complete this reading, reflect on the following questions:

- Which social determinant do you perceive as the toughest barrier to overcome?

- What are the prominent social determinants that pose as challenges/barriers in your community?

- Can you think of any way to improve the current situation in your community?

You should now have a better understanding of the approaches commonly used by helping professionals when working with clients with substance use problems. However, before moving on to learning about the different treatment options and interventions available to AOD clients, you will need to be aware of the ethical and legal considerations in the AOD field. Firstly, you will learn more about the AOD system in Australia.

Alcohol and Other Drugs System in Australia

The AOD system in Australia includes the government, non-government organisations (e.g., religious organisations and self-help groups), and private organisations (e.g., private hospitals and private treatment and service providers). All of them collaborate to provide the full spectrum of AOD services in Australia in the following six areas (adapted from NCETA, n.d.):

Policy

The National Drug Strategy, which you have learned earlier, is the overarching drug policy in Australia and The Health Council is responsible for this policy. In addition to that, each jurisdiction have their own strategies and action plans to address local AOD matters.

Development and Enforcement of Legislation

As mentioned, legislation surrounding AOD is developed at two levels: national and jurisdictional. Different parties such as national and local police, other law enforcement agencies, and regulatory bodies play a role in being responsible for the enforcement of these legislation.

For example, the Victoria State Government established The Severe Substance Dependence Treatment Act 2010 (SSDTA), whereby individuals with severe AOD dependence could be detained and treated in a treatment centre. This applies to individuals who are incapable of decision-making that relates to their AOD use, personal health, welfare, and safety due to AOD dependence (Health Victoria, n.d.).

Treatment Services

AOD services are provided by government, non-government, and private providers. Other than the government, non-government organisations also deliver AOD services that are funded by the government.

Prevention Programs

In Australia, many organisations including government, non-government, and community ones are involved in the prevention of AOD use and its harms. For example, at the national level, National Tobacco Campaign is a national campaign aimed to reduce smoking rates in Australia by discouraging the use of tobacco; at the jurisdictional level, Western Australia launched Drug Aware to prevent youths from using illicit drugs.

An example of community-based action is The Local Drug Action Team (LDAT) implemented by the Alcohol and Drug Foundation (ADF), an independent and not-for-profit organisation in Australia. It is funded by the Australian Government which aims to empower community organisations to work together to prevent and minimise the harm from AOD (ADF, n.d.).

Research

There are four research centres in Australia that receive funding from the Australian government to which conducts research to understand more about a broad range of AOD issues. These centres NCETA at Flinders University, NDRI at Curtin University, NDARC at University of New South Wales, and CYSAR at the University of Queensland.

Advocacy

Many organisations represent the need of those who are impacted by AOD use (including the individual and those around them) and AOD service providers. For example, the Australian Alcohol and other Drugs Council (ADCA) and Family Drug Support Australia. There are also jurisdictional peak body that represents the non-government AOD sector, such as Victorian Alcohol and Drug Association (VAADA).

Find Out More

Are you aware that each State and Territory has their own local campaign against AOD use and its harm? For example, Victorian government has developed “Get Ready Program” which is an evidence-based education program for Year 7 – 9 students in school.

Take some time and find out about what campaigns or programs that are implemented in your jurisdiction.

Codes of Ethics, Codes of Conduct, and Codes of Practice

After learning about the AOD system in Australia, you will now learn about the guidelines to adhere to when practicing as a helping professional. These guidelines can include the codes of ethics, codes of conducts, and sometimes, codes of practice. Different sets of standards and guidelines are developed by and for different professions to follow. These guidelines typically act as a benchmark for experienced community workers, but also as a guide for those new to the field.

| Codes of Ethics | Codes of Conduct | Codes of Practice | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose | Guiding workers to meet a standard of expected ethical behavior and acts as a guideline for workers when faced with ethical judgements and how to behave appropriately according to the specific situation. |

Guiding workers to behave and practice in a certain standard. Typically underpinned by codes of ethics. |

Similar to codes of conduct. Guiding workers to practice in line with expected standard of good practice. Typically underpinned by codes of ethics. |

| Focuses on | Ethical values and principles that the peak body, regulatory body, or organisation believes in and committed to follow. | Ethical behaviours and specific behaviours | Standard of good organizational and operational practices |

| Governs | Making decisions that requires ethical judgement. | Regulations about behavior. | Operational practices |

When clients are seeking treatment or support services, they are often in a very vulnerable position. Thus, it is very important that helping professionals are aware of their responsibilities towards their clients and their well-being. With these guidelines in place, helping professional can understand what is expected from them when working with clients as well as ensuring that their clients are receiving appropriate services and not taken advantage of.

To re-emphasise, while there is no current standardised codes of conduct or codes of practice for helping professionals in Australia, other guidelines can still serve as a foundation to guide your practice as a helping professional. This is because inherently, all these guidelines serves the same purpose – to ensure community workers uphold the appropriate ethical values so that the best possible standards of services are delivered to those who seek it.

Read

Reading F: Australian Community Workers Ethics and Good Practice Guide

As a helping professional, regardless of your position title, be it as a social worker or a mental health nurse, you are regarded as a community worker.

Mentioned earlier in this Section, as a helping professional you will be working with people who are the most vulnerable and marginalised in the community. Therefore, it is imperative that you have a good understanding of what is expected from you as a community worker and how to conduct your work accordingly.

Reading F is the Australian Community Workers Ethics and Good Practice Guide developed by the Australian Community Workers Association (ACWA) for community workers. Therefore, read through this set of guidelines and reflect on the following questions:

- Are there any ethical principles that stand out to you? Why?

- Do you think it is necessary to have these guidelines to keep professions in check? Why or why not?

- Is there any expected values or practices that you think may impose an ethical dilemma on yourself? If so, how would you resolve that?

Even though there are different guidelines available, they all have the similar central theme and are heavily emphasised not just for those working in the AOD sectors, but across all community workers. Therefore, we will have look at these specific guidelines in details.

Informed Consent

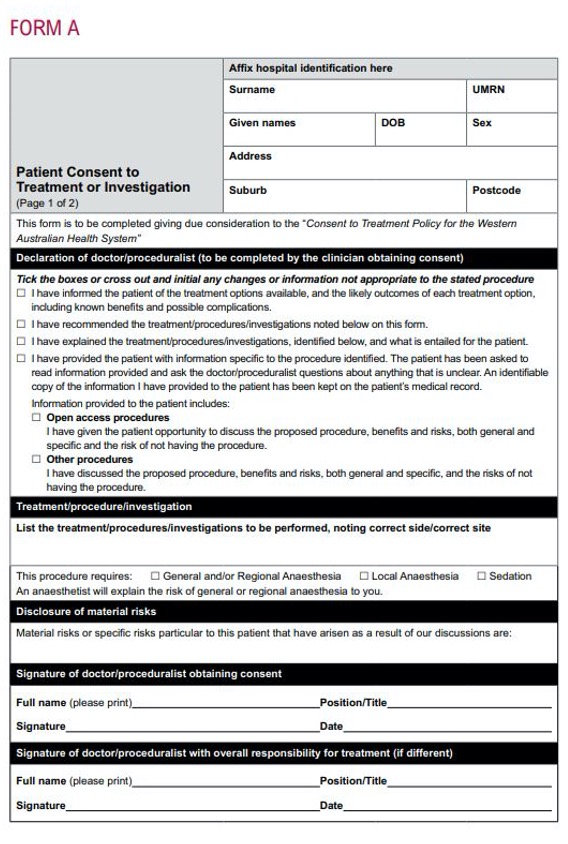

Obtaining informed consent from client is the first important step of establishing a professional relationship with your client. Informed consent involves your client or patient making a voluntary decision about their treatment plan or service, after getting informed by you with the full information about the treatment they may be receiving. This typically includes understanding the potential risks, complications, and benefits that may arise from the treatment. You must also inform your clients of any alternative treatment options and the consequences of these treatments or not receiving treatment. This is followed by a process of communication and shared decision-making between you and your client. This is typically obtained through writing and in the form of an informed consent document (see below an example of a generic informed consent form from Western Australia Department of Health, 2020):

Although the consent form shown above is a generic one used across different health practitioners, the statements are similar to what you will provide to your client. In addition to the signed consent form, a valid informed consent requires your client to fully comprehend the information provided by you and has an opportunity to clarify any information that they find confusing. In some situations, your client may require an interpreter if they find it challenging to understand the information they were given with or to communicate their concerns with you. And of course, any informed consent obtained has to be voluntary and not provided under circumstances of coercion or influence. Read the extract below about the challenge that you may face when it comes to how you release information to your client.

Most professionals agree that it is crucial to provide clients with information about the therapeutic relationship, but the manner in which this is done in practice varies considerably among therapists. It is a mistake to overwhelm clients with too much detailed information at once, but it is also a mistake to withhold important information that clients need if they are to make wise choices about their therapy.

(Corey et al., 2019, p 153.)

Therefore, you have to be careful and conscious when sharing information with your client such that they are equipped with sufficient information but not too overwhelmed with new knowledge. Encourage your client to seek clarification or ask you questions regarding what you informed them to make sure that you client is able to make a genuine informed decision and thus providing a valid informed consent. It is also extremely important to remember that you have to obtain a valid informed consent from your client before providing further services. If you fail to do so, you may be in a legal violation such as a criminal charge of assault or civil action (Queensland Health, 2017).

Case Study

Joshua

At the first counselling session, Joshua, an AOD case worker, did not provide sufficient information to his client about his treatment options. Joshua suggested the client to participate in community-based programs such as weekly-based support groups. However, Joshua failed to explain to the client that there are alternative treatment options available such as counselling sessions. He also did not notice that the client was having some difficulty trying to comprehend how the program works.

After finished explaining, Joshua asked that the client sign the informed consent form without making sure the client fully understood what was mentioned and did not provide an opportunity for the client to seek clarification. The client felt overwhelmed and pressured but just signed off the form without asking any questions.

Take some time to reflect the following questions:

- What are some of the legal and ethical violations that Joshua may have violated?

- What would you do if you were in Joshua’s position?

Privacy and Confidentiality

You should recall that it is extremely important to protect your client’s privacy by ensuring all information your client disclosed are well-protected. There are legislations put in place that protect your client’s confidentiality and privacy, and as a helping professional, you may be facing legal consequences if these are violated. Confidentiality is typically referred to how information obtained in a professional relationship can be treated. It can also be defined as “the right of a client to ensure all of the information relating to their health care is not shared with other parties without their permission” (Crane, 2012, p. 43).

For example, as health service providers, you have the obligation to adhere to the Privacy Act 1988, which puts out a set of guidelines on how you, as a helping professional, can collect, use, and disclose your client’s health information. Health information can include family history, details of major issues, future treatment action plans and arrangements for next meeting. Further, you also have to ensure that your client’s personal details are also kept private and confidential.

Find Out More

As a helping professional, you will definitely handle sensitive health and personal information about your clients. You have to be very cautious on how you handle these information.

Before continuing to the next part, take some time to read this guide to health privacy developed by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner: Guide to Health Privacy. After reading the guide, think about how this Act protects your client and how it may make them feel safer to seek professional help relating to their AOD use. Imagine if you are the client, do you feel safer?

Of course, the ideal situation would be that your client consents to disclosing information they shared to others, such as discussing issues with family and friends. However, this is not always the case. Under certain circumstances, you are required to disclose your client’s information despite having the obligations to maintain their privacy and confidentiality. These typically falls under one of the following situations and mostly occur when you have a legitimate concern for your client’s or someone else’s safety (adapted from Stone et al., 2019):

- disclosure of client’s information during supervision or case management

- client threatening to harm themselves or others

- disclosure of a serious major crime, e.g., murder or terrorism

- child involved being at risk of abuse (mandatory reporting)

- court orders – a subpoena for client’s records

In order for your client to fully comprehend when you can and cannot maintain confidentiality, you have to inform your client before any information is shared by them, i.e., ensure your client understands there is no absolute confidentiality before proceeding further. Extra steps can also be taken such as constantly making sure you do not breach confidentiality during sessions with your clients.

Mandatory Reporting

As helping professionals , there will be times that you come across clients or their family members whom you suspect are involved in child abuse or neglect. In these situations, you have the legal obligation to report these incidents to government child protection services.

Although all jurisdictions have introduced mandatory reporting laws, there are differences that exist in the laws across all jurisdictions – mainly who has to report (e.g., dentists, teachers) and what types of neglect and abuse (e.g., sexual abuse, emotional abuse) have to be reported. However, all jurisdictions have legislations that protect the reporter’s identity from disclosure. In other words, when you make a report of suspected child neglect or abuse, your identity will not be disclosed and you are not liable for any civil, criminal, or administrative proceedings.

Reflect

Before continuing to the next part, take some time to read the case study below:

On Ren’s second visit he brings his 1-year-old daughter Leia, as his child care arrangements fell through. Leia is in a soiled nappy and pyjamas, her hair is matted and face dirty. You notice bruises on her arms and legs. When you mention this, Ren explains that she is a very active kid who loves climbing. Though Leia cries throughout the appointment, Ren doesn’t pick her up. Ren has a new roommate, Tahlea, who he sometimes drinks and smokes weed with. He says that he often feels overwhelmed by having to care for Leia all on his own, and that he sometimes leaves her at home with Tahlea to go to the pub. He typically drinks 6–8 cans of Jack Daniels and Coke a night, which he says make him feel calmer (Adapted from AIFS, n.d.).

Now, reflect on these questions:

- As a helping professional, how would you respond to this situation?

- Taking into consideration whichever jurisdiction you’re in now, what action can you take?

Find Out More

Different jurisdictions have different legislations on mandatory reporting. As a helping professional, you are very likely to come across children or young people at work. Therefore, it is important that you familiarise yourselves with the legislation in your jurisdiction.

The Australian Institute of Family Studies (2020) has put together a resource sheet about mandatory reporting laws. They also set out the different mandatory requirements for all jurisdictions and the relevant laws. Visit the website here: Mandatory reporting of child abuse and neglect and take some time to find out more about the legislation in your jurisdiction.

Stigmas Related to AOD Use

As helping professionals, your client may be in a very vulnerable state when seeking help and therefore value their privacy. If your client’s information is shared with someone else without their consent, especially those pertaining to their AOD treatments, they may receive stigmas from society. In turn, this may negatively affect their treatment progress and/or well-being, and may result in your client not seeking for help such as ceasing any ongoing treatments.

Stigma is the process whereby an individual or a group are viewed in a negative light because of a specific characteristic they possess or the way they behave. According to social norms, these characteristics and behaviours are generally not “normal” and not accepted by the general society (ADF, 2020). When people are stigmatised, they are usually stereotyped and socially excluded, and they may receive unequal treatment across different aspects of their life. Research has shown that when people are stigmatised, they tend to be more stressed and may leave any treatment and support services that they have been receiving (Lancaster et al., 2017). Therefore, it is important to ensure that any information shared by your client are safe and secured, such that they do not face any stigmas from their communities and the society for receiving AOD-related treatment and support. This can also help to make sure that your client do not cease seeking for help due to stigmatisation and prevent further deterioration of their circumstances.

Records Management

You would need to record and keep case notes for each session you had with your client. Recall that case notes typically record all discussions, interactions, observations, and actions relating to your client. It can also include any discussion or interaction with other persons or services involved in the provision of support, such as referral information, telephone, and email correspondence (AASW, 2015). This information is usually kept for seven years, though it may vary according to your organisation’s policies. You need to be familiar with how you or your organisation manage clients’ records, as they are considered legal documents and they are part of your responsibility to your client. In other words, it is your responsibility to familiarise yourselves with how case notes and client records are stored and who has access to these documents. Similar to what you learned about confidentiality, nobody outside the limits of confidentiality (e.g., legal obligation) should have access to clients’ records, unless your client provides consent (Stone et al., 2019).

Records act as evidence of client engagement and their treatment progress. It also holds you, the helping professional, accountable for the choice of any treatment or services and the rationale behind the choice. In addition to that, records are kept to assist you in organising your thoughts and feelings when interacting with clients. Hence, it should be written immediately or within two working days after client contact to prevent any misinformation. However, by keeping records, it increases the risk of breaching confidentiality. For example, case may get misplaced or lost when transporting them between sites. Further, recording case notes may make trust-building with your client difficult. As helping professionals, your clients may be vulnerable to legal prosecutions due to illicit substance use. They may have the fear that any information disclosed to you may be recorded and used against them in the future by law enforcements (Bond, 2015).

In short, there are pros and cons of keeping case notes and clients’ records. Therefore, you should always inform your client that you will take down case notes, the purpose of doing so, and how these records are being used. You should also ensure that your client fully understands where this information is stored and who can access them.

Children in the Workplace

There are two general circumstances that you will have interactions will children or youths: your client is under 18-years-old, or your client involves a child’s presence during session.

Working with Clients under 18-years-old

It is often challenging and tricky to work with clients who are underage (typically under 18 years-old), especially when it concerns their ability to provide informed consent to treatment and support services. The client’s young age can also influence and complicate how the limits of confidentiality are set. These are usually determined on a case-by-case basis and guided by Gillick Competence. Gillick Competence, sometimes known as the Fraser Guidelines, is a checklist commonly used in UK to determine the capacity of a young person in certain situations. Australia also follows this ruling, which recognises young people as an individual and that they have the right to provide informed consent as long as they are proven to have the maturity to do so. Thus, it is important that as a helping professional, you respect and acknowledge the autonomy of young people (Crane, 2012).

As a general guideline, Queensland Health (2019) suggested the following when assessing young people’s capacity to give informed consent, or make informed decisions about their treatment or support services:

A child of 15 years or above would normally be expected to have sufficient maturity, intelligence and understanding to fully understand the proposed treatment in order that they are able to provide valid and informed consent. Assessing capacity is a matter for professional judgement. Judgement about a child’s competence involves consideration of:

- the age, attitude and maturity of the child or young person, including their physical and emotional development

- the child or young person’s level of intelligence and education

- the child or young person’s social circumstances and social history

- the nature of the child or young person’s condition

- the complexity of the proposed healthcare, including the need for follow up or supervision after the healthcare

- the seriousness of the risks associated with the healthcare

- the consequences if the child or young person does not have the healthcare

(Queensland Health, 2019)

It is also worth remembering that when your client (under 18 years old) is deemed Gillick Competent (i.e., have the capacity and maturity to consent), you should afford them the same confidentiality privilege as you would with an adult client. Youths who are underage may have strong intentions to seek help with their AOD use problem or to seek support about their peer’s AOD use. However, they tend to be concerned about confidentiality issues, especially whether their parents will be informed about their circumstances, and thus refusing to seek help (English & Ford, 2007, as cited in Crane, 2012).

However, if your underage client is deemed to be not Gillick competent, you would most likely need to establish parental consent before commencing work with the child. With that said, your organisation may have their own guidelines regarding parental consent, so always check with your organisation before making any decision.

Also, each jurisdiction has their own legislation that requires individuals who wish to commence child-related work (including both paid and unpaid work) to undergo a screening for criminal offences. Most jurisdictions require a Working With Children Check (WWCC) which is a more thorough and targeted check than a police check, and aims to assess the risk level an individual poses to children’s safety (Douglas, 2018). Sometimes, a WWCC is also known as other names in some jurisdictions, such as Blue Card in Queensland and Ochre Card in Northern Territory.

Find out more about the WWCC system in your respective jurisdictions in the link below, and make sure you keep yourself updated with the relevant requirements:

- Overview of the WWCC System and what the check comprises of in each jurisdiction and each jurisdiction’s legislations for child-related work: Pre-employment screening: Working with children checks and police checks.

- WWCC System and the requirements in each jurisdiction, e.g., what records are checked, who is required to undergo screening: Part B: State and territory requirements.

In addition to the framework developed by respective jurisdictions, some organisations have their own policies regarding working with children. Therefore, it is also your responsibility as a helping professional to check with your organisation regarding these policies, and to adhere to them.

Work Role Boundaries

We understand that it may be challenging or confusing to maintain professional boundaries with their clients. Especially in this field, your client will most likely share many private and personal situations with you. But you have to be careful, as sometimes, helping professionals may become over-involved in their client’s lives and this is dangerous as they may potentially develop a personal relationship with their clients. Further, some helping professionals entered the field with lived experience of AOD use and/or their impacts and thus use their background to help inform clients’ treatments and support. However, this may also pose as a challenge for them to draw a clear line between professional and personal boundaries.

As a helping professional, you have to remember that while maintaining your client’s wellbeing is your responsibility, you need to be careful to not overstep the professional boundary. Below are the summarised key challenges that you may face as a helping professional (adapted from Crane, 2012):

- Dual Relationship: Other than your professional relationship, you may have some other form of relationship(s) that has different obligations with your clients. For example, you and your client may be attending the same religious worship place, or play in the same basketball team, or even have a personal friendship. Even though it is encouraged that you should avoid any dual relationships with your client, it cannot be avoided under certain circumstances. In these instances, you need to manage these relationships and clearly distinguish them according to the context (e.g., social vs. professional).

- Conflicts of Interest: This can arise easily when a dual relationship is involved between you and your client. Conflict of interest occurs when the decisions you make and how you behave are influenced by your own interest, rather than your client’s interest. However, it is acknowledged that there are times you may be faced with a dilemma about whether you should act in your client’s interest or the public’s interest. For example, your client may be smoking tobacco to help relieve severe stress but it affects their family members who has to take in the second-hand smoke. How would you respond to that?

- Boundary Violations: It is a serious matter when a helping professional oversteps the professional boundary and engage in a non-professional relationship with their clients. For example, an AOD counsellor Jeremy found out that his client owns a restaurant and he frequents it with his friends. Subsequently, he became close friends with this client and crossed the professional boundary. When this happens, Jeremy may not put his client’s interest first and this neglects and violates the client’s rights. This is also important for helping professionals with personal AOD history – they should not be over concerned with their client’s progress outside of their professional capabilities and context.

- Role Approximation: When starting a professional relationship with your client, they may approximate this new relationship to an existing template based on their past experiences or similar relationships with others. It is quite common that clients are unable to understand the professional boundaries that you put in place. This is especially common among youths, whereby the equality and respect shown to them as a helping profesisonal may be regarded as you being a personal friend to them. You have to learn to navigate this ethical consideration by drawing and negotiating boundaries to your clients, and ensure that they fully understand it and not view it as you being “rude” or “cold” to them.

Other than the key challenges listed above, if you are working in a small or rural community, you will most likely have multiple relationships with your clients. Barnett (2017, as cited in Corey et al., 2019, p. 286) mentioned that the goal for rural community workers are “not to avoid all multiple roles and relationships but to manage these relationships in an ethical and thoughtful manner.” Indeed, this is one of the realities, or rather, challenges that you have to face as a helping professional in a small community. You have to learn how to navigate these boundaries in a delicate way, such that you are able to provide professional help to your client while still practicing according to the ethical guidelines.

For example, the shopkeeper at the town’s only bookstore that you frequent is one of your clients. You have no way to avoid your encounter with the client as it is the only bookstore that is within reach. What would you do in this situation? One way to tackle this is during the initial session, you need to let your clients know the likelihood of encountering you outside of sessions. You should also discuss with your client how they would like you to manage interactions outside of sessions. See below an extract from Corey et al. (2019) on how a rural counsellor handled multiple relationships:

I discussed with my clients the unique variables pertaining to confidentiality in a small community. I informed them that I would not discuss professional concerns with them should we meet at the grocery store or the post office, and I respected their preferences regarding interactions away from the office. Knowing that I would not talk with anyone about who my clients were, even when I might be directly asked. Another example of protecting my clients’ privacy pertained to a manner of depositing checks at the local bank. Because the bank employees knew my profession, it would have been easy for them to identify my clients. Again, I talked with my clients about their preferences. If they had any discomfort about my depositing their checks in the local bank, I arranged to have them deposited elsewhere.

(Corey et al., 2019, p. 271)

Managing and Clarifying Boundaries with Clients

As mentioned, it is challenging and complicated to effectively manage a professional boundary with your client. To do so, you really have to be very clear and explicitly inform your client during the first session. Failure to do so may further complicate the professional boundary; when you inform or enforce the boundaries in later sessions, you may risk destroying the client’s trust and hurt the therapeutic relationship built. As a result, the client may feel violated and betrayed and may even cease any future sessions with you. Here are some strategies that you could adapt and use to manage and clarify boundaries with your clients (adapted from Crane, 2012):

- Explicitly stating the professional boundaries of the relationship during initial session, such as clarity about your role, approved and appropriate modes and times of contact, clearly explain the difference between being “friendly” and being a friend, explain appropriate and inappropriate behaviour with examples.

- Explore and discuss client’s conceptualisation of boundaries when they seek for your personal information.

- Decline to respond to client’s comments or behaviours that may be intentionally seeking a response inconsistent with the professional relationship. For example, your client wants to seek affirmation from you about certain types of AOD use.

- When faced with any concerns, speak to someone appropriate such as a professional supervisor or a respected peer.

Limitations to Your Professional Role

It is extremely important that you remember you should not assume the responsibilities of other health professional treatments or services. You should only accept the responsibilities that are within the bounds of your specific training, for example, as a helping professional, you do not provide counselling services to your clients unless you have undergo specific training and permission to do so. When your client requires services that are not within your capability, refer them to the appropriate services. Therefore, you need to have the ability to assess which services are suitable and accessible for your client, if required. To do so, you would need to keep yourself updated with the relevant treatment and support services available in your local area (Crane, 2012).

Reflect

As a helping professional, it is common that you constantly face dilemmas, especially when navigating between your personal and professional life. Before continuing to the next part, take some time to read the scenario below:

Once I was at a big concert at the local pub and one of my clients rocked up with some mates for a drink as well. We’ve spotted each other and had a brief chat, and then I’ve wished them well and politely excused myself back to my friends. But then I’ve been in a conflicted situation. My friends asked me who the young person was, but I want to preserve their confidentiality so I’m cagey about the answer, which makes them suspicious. Do I just stay and keep drinking with my mates? Or do I have to ease off and have a quiet night because I don’t want to be seen to be drinking too much in front of the client? Or do I ask that we move somewhere else? (Adapted from Crane, 2012)

Now, take some time to reflect on these questions:

- What would you do if you’re the helping professional in the case study?

- Would you modify how you manage the different boundaries? If so, how?

Human Rights

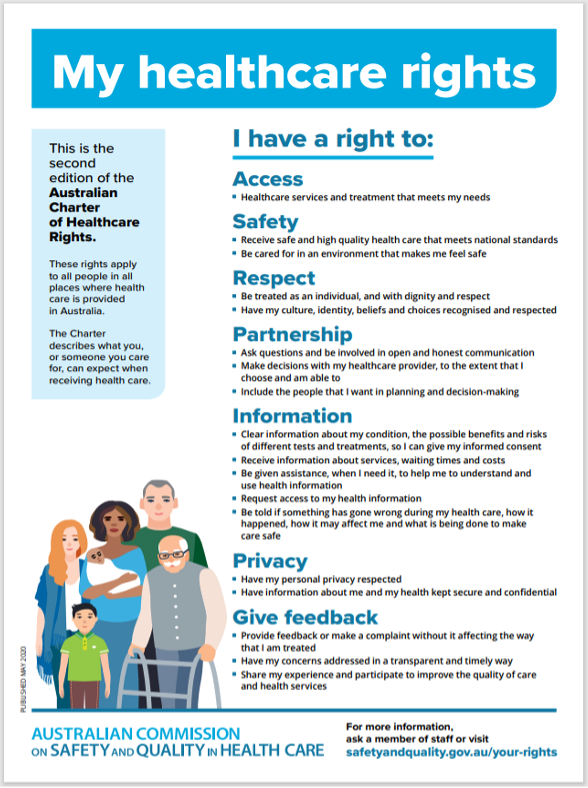

Human rights can be defined in different ways. One of the simple definition is that human rights recognise and respect individual’s dignity and can be in the form of moral and legal guidelines that promote and protect an adequate standard of living (AHRC, n.d.). These rights are laid out in various international agreements or treaties between governments to provide an agreed set of human rights standards. Methods are put in place to monitor how these treaties are being implemented.

Within Australia, human rights legislations are also put in place to respect and protect individuals of their rights and from any form of discrimination. For example, you learned about the Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 that protects our basic human rights. However, often individuals with AOD use problems tend to be denied some or all of their basic human rights. Typically, this is due to the social stigmatisation that individuals who are associated with AOD use should not be given the basic human rights as they are often incapable of thinking or feeling properly or the society perceive that these individual do not deserve to have basic human rights (QMHC, 2018).

“They assume that we’re all low lives, dole bludgers…A lot of people here, including myself, we’re very switched on. We’ve done apprenticeships, we’ve got certificates and degrees… it’s just that we’ve been stuck at a certain point in our life.”

The judgement does come in, when you really need that help. So you get knocked back a few times, and that’s what makes you go back out using.”

“One time I went into hospital for something. One of the doctors said, ‘She’s a bloody drug user. No use keeping her in hospital…”

“The first thing the ambulance driver did was tell the doctors it’s just alcohol withdrawal and I got told to leave… I had a temperature of 41.9… [it’s] because I’m homeless and alcoholic.”

(QMHC, 2018, p. 3)

The extract above are taken from interviews with individuals from a research by the Queensland Mental Health Commission (2018). It showed that there was and still is, a lot of stigmatisation and discrimination around AOD related issues. The surprising part was that these negative views not only came from the society, but also specifically those working in healthcare. Therefore, as helping professionals, it is extremely important that you can be empathetic and not judge your clients on their AOD related problem, and not deny your client any treatments or support services. When they experience these stigmatisation or discrimination, they may be reluctant to seek for help related to their AOD use problem, as shown in the extract above. Ultimately, this may lead to a vicious cycle whereby they develop a further dependence on problematic AOD use, which could bring more harms from AOD use (QMHC, 2018).

In addition to discrimination due to history of their AOD use, they may have also experienced discrimination previously. Similarly, you have to be understanding about their history and provide equal opportunities and resources to all clients without bias. In addition to helping professionals ethical values, there are also various anti-discrimination laws out in place to protect people’s rights. In other words, it is unlawful to treat someone else differently, or rather, discriminate an individual based on their protected attributes. These include age, disability, sex, and other personal attributes (Attorney-General’s Department, n.d.).

Remember, your clients are in very vulnerable states and as helping professionals, you should display a non-discriminatory and non-judgemental attitude and respect your client’s rights when they seek for help.

Duty of Care

You might have heard of duty of care if you have been working in healthcare-related fields. The principle of duty of care mentions that as a helping professional, you have “an obligation to avoid acts or omissions, which could be reasonably foreseen to injure or harm other people. This means that you must anticipate risks for your clients and take care to prevent them coming to harm” (Department of Health, 2004b).

In other words, if an individual, which in most cases, your client, relies on you be to be careful within reason, then you owe them a duty of care. You have to be aware of the nature of care you are providing in which your client may be relying on. If you fail to perform your duty of care (can involve doing something or failure to do something) and it leads to injury or harm on your client or a third party, you can be held responsible for it. In these circumstances, harms can be either physical or emotional.

Due to the nature of the AOD field, duty of care is extremely important and relevant to your role. This is because there will be times whereby your clients are under AOD influence and may inflict harm on themselves and others. Therefore, as a helping professional, you need to have the ability to ensure the safety of your client as well as the safety of others, including your personal safety (Crane, 2012).

Reflect

Read the case study below (adapted from Department of Health, 2004):

You are a helping profesisonal at an accommodation service and Paulo, one of your residents, arrives one night after curfew and demands to be let in. You notice that he is clearly under AOD influence but you are aware that he will not go away because he has nowhere else to go and you feel reluctant to call the police because of his history. You decide to let Paulo in to make sure he is safe but he quickly becomes more and more aggressive. He starts to get loud and wakes the other residents, and he also verbally abuses one of the residents. A while later he reveals that he has a weapon and he threatens to harm himself and take you all with him.

If you are in Paulo’s position, what actions will you take? Would you have done something differently at the start? Also, keep in mind that you have responsibilities not only to Paulo but also other residents, and yourself. So how would you prioritise the safety of everyone present?