In this section you will learn about:

- The core legal and ethical responsibilities of an allied health assistant.

- Common practices used to ensure adherence to both legal and ethical requirements.

Supplementary materials relevant to this section:

- Reading D: A Quick Guide to Australian Discrimination Laws

- Reading E: Informed Consent

- Reading F: Statutory Schemes

- Reading G: Mandatory Reporting of Child Abuse and Neglect

- Reading H: WHS Code of Practice

In the previous section of this module, you learned about the key sources of information that guide allied health practice, including codes of ethics, practice standards, legislation, and organisational policies and procedures. In this section of the module you will learn more about the specific legal and ethical responsibilities of effective allied health practice and how allied health workers comply with these responsibilities.

Legal and ethical frameworks support safe, effective, and fair delivery of services. This means practicing in a way that acknowledges, respects, and protects the rights of clients. These rights include the right to:

- Have their individuality and beliefs respected

- Be fully informed of the service to be provided

- Autonomy (to make their own decisions)

- Confidentiality; protection of their information to the greatest extent permitted under law

- Professional and competent service.

- Receive treatment that is responsive to their individual needs.

- Make a complaint about their service.

Health administrators are responsible for protecting the rights of clients. The key responsibilities, adapted from AAPM's Code of Ethical Conduct include:

- Respecting the basic rights of clients: clients have a right to receive safe and ethical services, without discrimination.

- Respecting the client’s right to privacy and confidentiality: Clients deserve for their privacy, dignity, rights, and health to be respected and kept confidential.

- Prioritising client safety and well-being: Communication with clients should be presented in an open and effective way to promote health, well-being, and safety.

- Delivering a professional and competent service: Allied health assissants have a responsibility to deliver quality practise through continual professional development and relevant and appropriate skills and knowledge.

Some of these principles are supported by legislation; others are predominantly expressed in ethical codes and practice standards. The remainder of this section of the Study Guide will explore these key allied health assistant responsibilities, the legal and ethical requirements underlying them, and the common practices used by allied health assistants and allied health organisations to promote compliance.

A core responsibility is to respect the rights of clients. This includes providing respectful, non-judgmental, and non-discriminatory service to clients and promoting self-determination. These rights are protected by both legal and ethical frameworks as well as a range of typical organisational requirements. Professional standards also address these rights. For example, the AAPM Code of Ethical Conduct enforces the ethical principles of justice – that people should be treated equally, affording everyone their basic rights ¬– and fairness – to act impartially, regardless of personal emotions, interests to issues and outcomes that arise. Within these, AAPM outlines the below principles and corresponding guidance statements below:

| Ethical Principle |

|---|

|

Integrity: To be consistent in action, values, methods, measures, principles, expectation, and outcomes. Respect: To acknowledge that every human being, regardless of race, religion, gender, age, sexual and gender diversity, or other individual differences is entitled to unconditional respect and has a right to maximise his or her potential providing it does not infringe upon the rights of others. Dignity: To value the uniqueness of every individual and uphold the responsibility to provide services around each individual and their specific needs. |

| Guidance statements for practice |

|

To act with integrity is to: To act with respect is to: To act with dignity is to: |

Non-discriminatory practice is also required under legislation. There are a range of anti-discrimination laws in place that aim to protect people from certain kinds of discrimination in public life and from breaches of their human rights. As a health administrator, you need to be knowledgeable about this legislation and ensure that you comply with it. Ultimately, the Australian Human Rights Commission has statutory responsibilities under these laws and has the authority to investigate and resolve complaints related to human rights violations (which includes discrimination). The Commission can reprimand organisations, as well as report individual workers to their regulatory body if they find breaches. If the breach is serious, a worker can even lose their job and ability to work in the sector.

Read

D – A Quick Guide to Australian Discrimination Laws

Reading D provides a broad overview of anti-discrimination legislation in Australia, including laws that operate at a federal level and those at a state and territory level. As allied health assistants you must comply with both levels of laws.

Most allied health organisations also have specific policies and procedures, including those related to equal opportunity and discrimination within the workplace and client charters that set out how client rights will be protected while they engage in allied health services. Client charters typically outline what services the organisation provides, what clients should expect from their service, and the rights and responsibilities of both allied health workers and clients. Additionally, most organisations will have specific policies in place to assist health administrators in working with clients from diverse cultural backgrounds, including cultural protocols and procedures for the use of language and cultural interpreters.

Let’s look at an example of how a client’s rights can be violated below.

Case Study

Malik, a 38-year-old Pakistani immigrant from Melbourne, is seeking treatment from an allied health organisation that specialises in Psychology. He visits the clinic and is greeted by the health receptionist, Sarah, who becomes uncomfortable when Malik tells her that he is Muslim and has sought out treatment because he is having marital difficulties with his wife. Sarah assumes that Malik is oppressing his wife and does not want to work with him even though her organisation’s services are open to all. She tells Malik that he is not eligible for the organisation’s services and that she cannot help him.

In this case, Sarah is not only breaching the AAPM Code of Ethical Conduct she is also breaching international, commonwealth and state legislation related to discrimination – specifically the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Commonwealth), and the Equal Opportunity Act 2010 (Victoria).

Sarah is also breaching organisational policy, which states that client eligibility is not affected by religious affiliation. The consequences of these actions can include disciplinary action by the organisation and charges under the Acts outlined above.

Following organisational policies and procedures and relevant legal and ethical requirements is central to respecting the basic rights of clients. However, health administrators need to go further and maintain an awareness of their own values and how these values can impact upon their work with clients and their recording of information. In order to practice in a way that respects their client’s basic rights, it is crucial that health administrators do not impose their own values and beliefs onto clients. As such, they need to examine their own value system and consider how their personal beliefs may impact the client. While it is impossible to be value-free, health administrators should continuously engage in self-reflection and supervision to monitor for the impact of values and facilitate non-judgemental, non-discriminatory practice. In cases where health administrators hold particularly strong values, it is extremely important that they are aware of the potential impact of their personal values on the treatment process and documentation objectivity and monitor interactions carefully. Referral should be considered if a health administrator feels that their personal values may unduly influence the client’s treatment and negatively impact on a client’s autonomy and self-determination.

REFLECT

Why do you think it is so important for health administrators to avoid imposing their own values onto clients? What negative impacts do you think it could have on a client and the if a health administrator imposed their own values onto the client?

Clients have a legal and ethical right to have their private information kept confidential and allied health assistants have a responsibility to protect this right. With few exceptions, the client’s identity, the fact that they are receiving treatment (or another helping service), and everything discussed between a health administrator and their client is confidential, even if it does not seem like important or particularly sensitive information:

Confidentiality …. encompasses not only the words spoken between professionals and their clients, but also all records related to those interactions, and the identity of the clients. A professional is obligated not to disclose even the names of clients without their permission… … professionals are expected to provide an…environment in which client words cannot be overheard, their records are kept secure from unauthorised people, and their presence at the office is protected to the fullest extent possible.

(Welfel, 2016, p. 112)

Read

F – Statutory Schemes

In Reading F, you will find an overview of practitioners’ responsibilities with respect to privacy and confidentiality laws.

Health administrators (and allied health organisations) are also required to protect client privacy. The concept of privacy is broader in scope than confidentiality and relates to the ownership of information, as well as the gathering and storing of this information (Kämpf, McSherry, Ogloff, & Rothschild, 2009). Maintaining client privacy and confidentiality is a fundamental ethical principle supported in the AHANA Code of Conduct, as highlighted in the following extract:

| Ethical Principle | |

|---|---|

| Privacy and confidentiality: To value the privacy of individuals as an inherent right and acknowledge the right to privacy by maintaining confidentiality of information shared by patients and other stakeholders. (AAPM, 2023, p.13) |

|

| Guidance statements for practice | |

|

To respect privacy and confidentiality is to: • Respect and maintain the confidentiality of information acquired in the course of their professional duties and ensure policies are in place to prevent disclosure of such information, except when authorised or legally required to do so. |

|

There are also a number of laws that protect client privacy and confidentiality as well as detail exceptional circumstances when confidentiality should be breached. Some of the most important provisions can be found in privacy legislation, mental health acts, and mandatory reporting legislation (Kämpf et al., 2009). Let’s explore each of these now.

The Privacy Act 1988 (Commonwealth)

This piece of federal legislation regulates how personal information is managed. The Privacy Act includes thirteen Australian Privacy Principles (APPs), which apply to many private sector organisations as well as most government agencies and other bodies. The APPs provide specific rules to protect health information with disclosure (revealing information) prohibited “beyond its primary purpose” (i.e., diagnosis and treatment; Kämpf et al., 2009, p. 76). Disclosure is permissible only under specific circumstances, such as:

- If it is directly related to the primary purpose and within the client’s or patient’s reasonable expectations.

- If the client or patient consents to it.

- If disclosure is required or authorised by law.

All states and territories have enacted specific health records and information privacy legislation and you should ensure you are familiar with the legislation relating to your own jurisdiction. General information on state-based requirements can be found in Reading F. However, information can become out-dated very quickly, and it is your responsibility to keep your knowledge of relevant legislation and regulations current.

Mental Health Legislation

Each piece of mental health legislation incorporates specific provisions that generally protect confidentiality in mental health settings. Although these acts may differ in some respects, they aim to protect information that clients may divulge to mental health professionals. These acts do allow for the disclosure of information in specific circumstances, such as:

- With the client’s consent.

- When the disclosure is required or authorised by the mental health legislation or other legal provisions.

- To nominated carers or guardians in certain circumstances.

- For the purpose of criminal investigations or criminal proceedings.

- For statistical analysis and research purposes, provided that there is compliance with further requirements (e.g., that the information is de-identified).

And even where mental health provisions do not apply, common law does. Ultimately, workers may be sued through civil law courts for compensation if a client believes that their confidentiality has been improperly breached (Kämpf et al., 2009).

Mandatory Reporting

Australian legislation mandates sharing otherwise confidential information in limited circumstances. One of these situations is where child abuse is suspected or confirmed. While mandatory reporting legislation does differ between jurisdictions, a child’s right to safety is considered paramount in all states and territories, and allied health assistants have a legal and ethical obligation to act where they have reason to believe a child has been abused, is being abused, or is at risk of abuse. There are penalties for nondisclosure where a mandatory reporter has reason to suspect abuse but fails to report this information. However, even if an allied health assistant works in a role or state in which they are not a mandatory reporter, they still have ethical obligations relating to child protection issues.

Read

G – Mandatory Reporting of Child Abuse and Neglect

Reading G provides an overview on Australian mandatory reporting laws – which vary slightly between each state and territory – and provides answers to some common questions asked about mandatory reporting.

Let’s look at an example of a medical receptionist dealing with the need to break client confidentiality due to mandatory reporting.

Case Study

Tim is a medical receptionist working alongside an Occupational Therapist who is providing treatment to a young child called Nathan. Before one of their sessions, Renee, Nathan’s mother, tells Tim that she is really struggling to control her son’s temper tantrums and that, even though she knows it is wrong, she slaps or punches him when he is having a tantrum. Tim works in the Northern Territory and, as such, is a mandatory reporter. His organisation’s policies and procedures also require him to make reports in situations of child abuse, and he is a member of the AAPM. Tim reports the information Renee disclosed to the Occupational Therapist he works with.

At the beginning of the treatment relationship Tim and the Occupational Therapist discussed the limits of confidentiality with Renee, and she signed a contract that noted the limits of confidentiality.

Tim and the Occupational Therapist address the need to report this matter with Renee. The Occupational Therapist says, “Renee, as we talked about at beginning of our treatment, there are some situations that I am legally and ethically required to report – and one of those situations is when I think a child is being harmed. What this means is that I will need to make a report in relation to what you have just told me. We can still work together and get you the assistance that you need to help manage Nathan’s behaviour. Do you have any questions?” Tim and the Occupational Therapist then follow their organisation’s policies and procedures, discussing the situation with the manager, and making a report to the child welfare authority.

If you are ever required to make a report concerning child abuse or child protection concerns, it will be vital to follow your organisation’s policies and procedures. This will generally include discussing your concerns with a manager or internal supervisor before making a report and using a specific organisational form or process to make the report. In some organisations it may only be within a supervisor’s level of responsibility to make a report to the relevant child protection authority, in which case you will be required to provide your supervisor with all of the relevant information. You will also need to document that you have made such a report (to your supervisor and/or the child welfare authority), as well as the reasons why you have done so. If you fail to keep adequate records, your decision may be challenged: your employment may be terminated, and you may face other professional and even legal sanctions.

All child welfare records and reports must be written in a clear, objective, and non-judgemental way. Some tips on appropriate reporting are included in the following extract:

- Relay information that describes exactly what happened as simple statements of fact.

- Be specific instead of vague or general.

- Be explicit in expressing yourself.

- Identify your sources.

- Be specific about dates and times.

- Be specific about the other person’s statements, writing exactly what they said, rather than your interpretation.

- Use moderate and graduated evaluative language instead of intense or emotional evaluative language.

- Use modality to show caution about your views or to allow room for others to disagree.

- Use objective and inclusive language.

- Include subjective evidence given to you by the person but make sure you identify the source.

(Adapted from Network of Community Activities, 2015)

It is also important to limit the reporting to child welfare authorities to only the information relevant to the child protection issue – such reports should not include information that is not relevant to the child safety risk. For example, it would be inappropriate to include information about children who are not being harmed or at risk of harm; to make comments about the personalities or habits of the people involved (unless there are habits directly relevant to the harm, such as current substance use); or your own judgments.

Let’s return to the case study above and imagine that Tim reports to the allied health professional, in this case an Occupational Therapist. Both the medical receptionist and the Occupational Therapist are mandatory reporters so the report should come from the both of them, either together or separately. In the report/s it was noted that Renee had disclosed that she had smoked marijuana prior to her children being born; that she has asthma and needs to take preventative medication daily; or that she regularly runs late for appointments. This would be disclosing information that is not relevant to the child safety risk. In such a case, while his sharing of child risk-related information was justified, he would have breached his client’s right to confidentiality in sharing the other information about her.

Protecting and Sharing Information

As a health administrator, it is vital that you respect any specific workplace requirements regarding records management and record keeping in addition to legislative requirements in your state or territory. AAPM’s Code of Ethical Conduct refers to record keeping within their ethical principle of honesty, as shown below:

| Ethical Principles |

| Honesty: To be truthful, trustworthy, straightforward, fair, and sincere in all professional and business relationships. (AAPM, 2023, p.11) |

| Guidance Statements for Practice |

| To act with honesty is to: • Recognise that honesty forms the foundation of trust, which is essential in all their professional relations. • Adhere to the highest standards of accuracy and transparency in their communications. • Comply with all relevant privacy laws and laws regarding the management of health records in the protection of personal information received from clients in a healthcare practice. • Ensure that their employees and associates also comply with this provision and monitor employee activities to ensure privacy and confidentiality standards are maintained. (AAPM, 2023, p.11) |

There are several responsibilities that a health administrator has with regards to record management.

Firstly, no unauthorised personnel should have access to a client’s information. This includes other allied health professionals that are not authorised to access this information. If a request is made for client records, this will need to be confirmed with the client/they will have provided informed consent to do so. Whenever a health administrator is required to breach a client’s confidentiality, they must follow their organisation’s policies and procedures. These often call for the health administrator to discuss the reasons for the breach with the client unless they believe such a discussion could have the potential to harm the client or a third party. Ultimately, if a health administrator is unsure about what to do in a particular situation, they should seek out the advice of their supervisor.

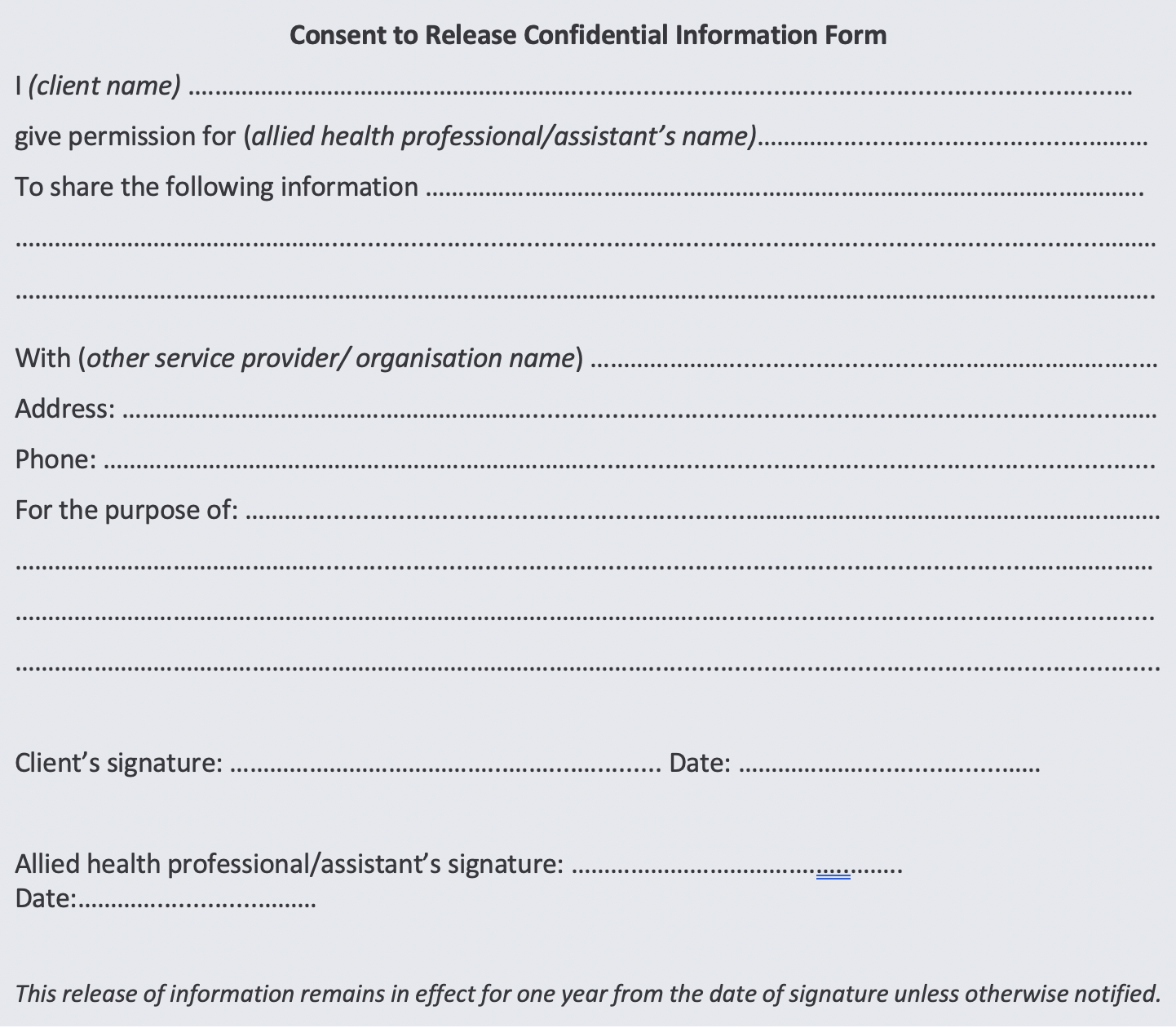

Due to the important nature of client confidentiality, allied health organisations typically require clients to sign a release of confidential information form as part of the referral process. This documents the client’s consent for the health administrator to release their information. An example of a consent to release information form has been provided on the next page.

Information might be shared for a number of reasons, with client consent. For example, health administrators often need to make referrals, may engage in collaborative work, and may need to act as advocacy or liaison, if required. In such cases, it is important to continue protecting client privacy and confidentiality. The only information shared should be that which is client has consented to, and which is relevant to the purpose of the information sharing.

When client information is being provided to authorised personnel, this should be done in a safe and secure manner. Physical copies, if mailed, should be transported in a sealed envelope, and electronic copies, should be transferred using a secured connection where no unauthorised third party could intercept the information.

In addition to legal and ethical protections for client privacy and confidentiality (other than in exceptional circumstances), most allied health and human services organisations develop policies and procedures to assist workers to meet their responsibilities. For example, organisations will have policies and procedures for the collection and storage of information, record keeping, referral, information sharing, and how to handle disclosures of abuse or other risks. These policies and procedures are designed to comply with legal and ethical requirements. An organisation’s record keeping procedures, for example, might include the following:

- Hard copy client files are to be kept in a locked filing cabinet.

- Electronic files are maintained on a protected intranet and client records can only be accessed by the individual allocated to that client, their supervisor, and specific members of senior management.

- Electronic files can only be accessed by user passwords and no files are accessible to people who are not staff of the organisation.

- Where there has been no activity on a client file for 90 days, that file is electronically closed and archived; any hard copy documents are placed in secure storage.

- Clients may request access to information contained on their file and/or a letter or report based on information in the file.

- Other people/services may not access information on a client file unless client consent is obtained in writing for the release of that information.

- Only aggregate (de-identified) data is provided to external agencies (e.g., funding bodies).

Expanding on the above procedures, health administrator’s also have a responsibility to ensure records are not left unattended in places where other clients may be able to access it, such as reception or waiting areas. If stored electronically, data needs to be properly backed up and password protected. Health administrators should ensure unauthorised individuals cannot compromise client privacy by never leaving a compute unattended if unlocked.

Lastly, according to the Health Records and Information Privacy Act 2022 (Cth), health service providers need to retain client information for seven years from the last rendered service (Information and Privacy Commission NSW, 2022). This is the minimum retention period; your workplace should have a record management/and retention policy that provides specific guidelines regarding how long to retain patient information/records for your workplace.

REFLECT

Take a few minutes to reflect on the common policies and procedures that you have learned about so far throughout your Certificate. Can you identify specific policies, procedures, or provisions that are designed to help protect client privacy and confidentiality?

Health administrators are responsible for providing services that are safe, meet practice standards, and act in the client’s best interests. This encompasses a range of legal and ethical considerations related to duty of care. Many of the legal and ethical responsibilities we have already discussed in this section of the module also relate to duty of care considerations.

In basic terms, duty of care means that allied health assistants have a responsibility to take reasonable steps to avoid clients coming to harm either through their actions or lack of actions. As mentioned in Section 1, there is no direct legislation outlining what constitutes “duty of care” in an allied health role. If an allied health assistant is accused of failing in their duty of care to a particular client (i.e., if they are sued for negligence) then the case will be decided in the courts based upon legal precedents, community expectations, and common professional practices. Allied health assistants can protect themselves by remaining up to date with relevant legislation, following standard practices, confirming their practices with more experienced colleagues, allied health professionals, supervisors, and complying with the appropriate codes of conduct. One specific area of allied health practice that allied health assistants must be particularly mindful of is maintaining open and effective communication.

Practitioner-Client Boundaries

An important component of client well-being involves the principle of ‘do no harm’. The practitioner-client relationship holds the potential for exploitation. Allied health assistants have an ethical responsibility to maintain appropriate professional boundaries and avoid any client exploitation. This is highlighted in the AAPM Code of Ethical Conduct:

| Ethical Principle |

|---|

|

Good faith: To exercise his or her responsibilities reasonably and not arbitrarily or for some irrelevant purpose, having regard to the legitimate interests of other affected parties. Empowerment: To facilitate autonomy, independence, and self determination in people and communities by providing appropriate resources and support. Communication: To value communicating with individuals in ways that are meaningful to them and enables them to understand and clarify the issues at stake. (AAPM, 2023, p. 13) |

| Guidance statements for practice |

|

To act in good faith is to: • Act with honesty and impartiality when providing service or advice to others (AAPM, 2023, p. 12) To act with empowerment is to: • Presume that individuals are competent in assessing and acting on their interests. To uphold ethical communication is to: • Communicate truthfully, concisely, and responsibly with others. (AAPM, 2023, p. 13) |

There are a range of behaviours that have the potential to blur the professional boundaries of the practitioner relationship. These are often thought of as ethical dilemmas and , though they are more likely to occur in professions such as counseling, are still important dilemmas to consider for any helping profession. Should these ethical dilemmas occur, allied health assistants are required to fully evaluate the potential impact of their actions before deciding how to proceed.

Examples of these include accepting a client’s invitation to an event such as a graduation, accepting a gift from a client, or attending the same social, cultural, or religious events as a client. Allied health workers are required to fully consider the potential repercussions of such behaviours and act appropriately because these ‘boundary crossings’ can lead to more serious boundary violations such as engaging in complex dual relationships (Corey, Corey, & Callinan, 2011). Typical indicators of potential boundary violations are listed below:

- Developing strong feelings for the client.

- Spending more time with this client than others.

- Engaging with a client socially outside of the service.

- Receiving calls at home from the client.

- Receiving gifts.

- Doing things for a client rather than enabling the client to do it for themselves.

- Believing only they can offer the right services to the client.

- Physically touching the client.

Whilst in isolation none of these behaviours may indicate a potential boundary violation is happening, they could be indicators of a potential problem.

(Community Door, n.d.a)

Once professional boundaries have been crossed, there is then a higher potential to become over-involved with the client and potentially violate the client’s rights. Therefore, if an allied health assistant finds themselves in a position in which they have not maintained appropriate boundaries, they have an ethical requirement to take appropriate actions. This usually involves consulting with their supervisor to determine the most appropriate course of action to reinstate professional boundaries or to make other appropriate changes for the client, such as assigning a different allied health assistant to their care

Other important aspects of promoting client safety and well-being involve providing Informed Consent and complying with workplace health and safety requirements.

Informed Consent

Informed consent involves two core components. The first involves providing the client with the information he or she needs to make a reasoned decision about whether to engage in the services being offered (e.g., what service provision will involve as well as its risks and potential benefits). The second is free consent – this agreement needs to be given freely and without coercion (Welfel, 2016). Informed consent means that clients have the opportunity to decline treatment or service once they have had an opportunity to find out about the risks and benefits of particular options. As an allied health assistant, delivering informed consent will likely fall within the responsibilities of the allied health professional you are assisting. However, it is an important ethical consideration to be aware of.

Informed consent ensures that clients are fully informed about the benefits and risks of recommended interventions before they are implemented, and are made aware of optional approaches to those being offered in the moment. A key purpose of informed consent is to protect the right of clients to self-determination. It provides an opportunity for clients to raise questions about the clinician, the work, and potential outcomes. In most circumstances, clients have the right to refuse or terminate clinical work. Informed consent serves a number of functions. It empowers people by providing them with information that enables them to make wise decisions. It encourages conversation about realistic goals and objectives, and ways to meet them so that clients know what to expect. Informed consent not only protects the client; it may also protect clinicians from lawsuits on the part of disgruntled clients who feel harmed or misinformed by their provider.

(Murphy & Dillon, 2015, p. 55)

Read

E – Informed Consent

Reading E focuses on clients’ right to give informed consent within helping contexts. Particularly you will learn about the legal aspects as well as how to educate clients about informed consent. This reading is written with the therapeutic relationship within a counselling context in mind; however, the information is relevant to any helping profession and will help you consolidate the information on this topic.

The fundamental ethical principle underlying informed consent is that of respect for client autonomy. By engaging in informed consent processes with each client, allied health assistants confirm the client’s right to manage their own lives and choose their own care (Welfel, 2016). The AAPM (2023) Code of Ethical Conduct requires that clients be given adequate information to make informed choices about entering and continuing the practitioner-client relationship:

| Guidance statements |

|---|

|

• Provide comprehensive information that others need to know in order to make informed decisions. |

According to common law, adults (i.e., those over 18) can consent to and refuse treatments and interventions. Younger people also have some rights when it comes to accessing or refusing services, although these situations are more complex (see A note on working with children, below). Informed consent is also protected by state and territory legislation, in the form of specific mental health acts (e.g., Mental Health Act 2015 (ACT)). These acts set out the rights of people with mental health issues regarding their care, including issues of consent and guidelines for when involuntary treatment may be enforced (although allied health assistants are not among those who can make involuntary treatment decisions or be involved in involuntary treatment provision). It is important to be aware of this act as, though allied health assistants may not work exclusively within mental health, there may be times when the mental health of clients is a consideration and, therefore, the Mental Health Act 205 will be a valuable resource.

If consent is not established, there may be professional and legal consequences for anyone who provides a service You must always gain informed consent before providing a service. Of course, this is not just a legal obligation: providing clients with sufficient information to make an informed decision and obtaining consent prior to starting treatment is essential to ethical practice, too.

Allied health organisations generally develop policies around formal written agreements/forms to assist in the process of obtaining informed consent. Allied health organisations will use a Services Agreement of some kind. Of course, allied health assistants do not just provide clients with a written contract – they also have a detailed conversation with each client, including confirming the client’s understanding. This means making sure that the client is informed about their own rights and responsibilities, the allied health assistant’s role and responsibilities, the process of treatment, and other levels of engagement, prior to the commencement of treatment. These conversations should:

- Provide the client with information about the services offered.

- Explain any specific approaches that the allied health professional uses.

- Provide an overview of what the client can expect to occur during treatment.

- Ensure that the client is familiar with organisational requirements such as payment sched-ules, cancellation policies, and termination procedures.

- Discuss the treatment process and the number of sessions suggested/required.

- Outline confidentiality and the limits to confidentiality. This includes ensuring the client is aware of circumstances in which you may be required to break confidentiality, such as:

- If I consider you to be at risk of seriously harming yourself or someone else.

- If your records have been requested by a court of law

- If another party or agency has requested your information, and you have agreed and provided your written consent to this

- Outline record keeping procedures and how clients can access their own information.

- Ensure that the client knows that they can withdraw their consent at any time and have the right to refuse to engage with any strategy or technique the allied health assistant or allied health professional uses or suggests.

Obtaining a client’s informed consent is an important legal and ethical step and it should be given due attention. As Welfel (2016) outlines, informed consent is not:

- Just some forms to be signed by the client at the initial session.

- Merely a brief discussion about the limits of confidentiality and nothing else.

- A risk management strategy undertaken primarily to protect allied health assistants and professionals from legal liability.

Obtaining informed consent is an important process that allied health assistants need to take time with. It is also important to understand that it is an ongoing process. Often clients will not readily understand all aspects of an initial informed consent discussion or will not recall initial discussions later in treatment; therefore, allied health assistant’s should revisit informed consent when seeking to implement new interventions later in the treatment process (Welfel, 2016). To see one-way things can go wrong, let’s look at an example of how a client’s right to informed consent can be violated.

Case Study

Adam attends an optometrist clinic to get an eye test done as a part of an investigation into frequent headaches. Adam has avoided getting his eyes tested for years due to a phobia of objects going near to or into his eyeballs. He tells the medical administration officer completing his intake of his phobia, and the medical administration officer says the optometrist will be doing standard testing to check his eyesight but does not tell Adam much more than that. Adam trusts that the medical administration officer knows what he is doing and consents to the treatment. Adam is then asked to sit down in a chair facing a machine where the optometrist performs a “puffer rest”; which is where puffs of air are blown across the surface of his eye. Adam is inadequately prepared for the treatment and suffers from a panic attack as a result.

In this scenario, although the medical administration officer has obtained Adam’s consent, it has not been informed consent (i.e., he has not been adequately informed about the proposed test and its possible benefits and risks). The medical administration officer could potentially be liable for damages if Adam decides to pursue legal action.

Reflect

What do you think the health administration should have done in the above situation in order to obtain Adam’s informed consent?

A Note on Working with Children

There are special considerations involved in working with children. The first involves parental consent. In Australia, guidelines regarding whether minors can consent to a service without parental knowledge and consent are not clearly defined and, when they are, ages of consent can vary across jurisdictions. But as ever, there are fundamental rights (the child’s) and ethical responsibilities (the health administrators/professional’s) here, too:

- Children should always be made aware what treatment will involve, as well as the limits of confidentiality and the allied health worker’s duty of care.

- The issue of the sharing of information with parents should be discussed and agreed to before treatment begins.

- Allied health workers must discuss all aspects of contracting – and conducting treatment itself – in a manner and language suitable to the child’s level of development and use multiple strategies to assess the child’s understanding. It cannot be assumed, for example, that a child client will understand terms like ‘confidentiality’, ‘privacy’, ‘contracting’, ‘allied health’, ‘service’, ‘duty of care’, and so on.

- Organisations that involve any degree of work with children should have specific policies and procedures in place to protect child welfare and enhance child wellbeing, by which their workers must abide.

Important note: Working with children is a specialised area requiring specific skills and also invokes a range of further legal and ethical responsibilities. While we provide basic information about working with children and young people in this course, students who want to work with children will need to undertake further study to gain competence in this area. Supervision with a practitioner experienced in working with children is also necessary.

Workplace Health and Safety

Workplace health and safety (WHS) is a vital consideration for any workplace, and all organisations should have comprehensive WHS policies and procedures; allied health assistants are required to comply with all relevant laws, regulations, policies, and procedures.

Read

H – WHS Code of Practice

Reading H provides a valuable overview of WHS considerations published by Workplace Health and Safety Queensland.

Each state/territory has its own body administering work health and safety – these are the best source of information on WHS requirements for your own jurisdiction:

| WHS Legislation – State/Territory | |

|---|---|

| Australian Capital Territory | www.worksafe.act.gov.au |

| New South Wales | www.safework.nsw.gov.au |

| Northern Territory | www.worksafe.nt.gov.au |

| Queensland | www.worksafe.qld.gov.au |

| South Australia | www.safework.sa.gov.au |

| Tasmania | www.worksafe.tas.gov.au |

| Victoria | www.worksafe.vic.gov.au |

| Western Australia | www.commerce.wa.gov.au/Worksafe |

While there are a wide range of WHS requirements, they all relate to the need to provide a safe working environment for staff, clients, and anyone else who may be present.

Allied health organisations typically develop specific WHS policies and procedures in order to ensure their own legislative compliance and allied health assistants are required to comply with these. Every-one in a workplace is responsible for minimising risks and engaging in safe work practices. While employers are responsible for developing policies and procedures that comply with relevant WHS legislation, workers and clients are responsible for following the policies and procedures related to work health and safety in their organisation. Workers, including allied health assistant’s, must be familiar with all WHS policies and procedures and seek clarification from their supervisor if they are unclear about anything. Ultimately, all allied health assistant’s must comply with their requirements under these policies and procedures and that they engage in appropriate hazard identification and management processes. Hazards are things that have the potential to cause harm.

While hazards will vary from workplace to workplace, in a health care context, some core WHS responsibilities include:

- Checking that walkways and access points are clear of hazards such as power cords, furniture, and other items.

- Ensuring that the chairs in the treatment room are supportive and strong.

- Making sure that the treatment room is well lit and ventilated.

- Maintaining familiarity with emergency procedures, including regularly practicing evacuation drills.

- Complying with policies and procedures related to personal safety and risk management.

Health administrators may be required to complete WHS checklists or other processes to check for hazards, document identified hazards, and take appropriate steps to control them. In addition, allied health assistants may be required to engage in consultation processes and contribute to the development of effective WHS policies and procedures within the workplace.

Specific WHS-related policies and procedures relate to the presence of children in the workplace. Children might come into the workplace as clients, the children of clients, or even the children of employees. Risk assessment and management procedures should account for the possible presence of children in the workplace. Ultimately, the environment should be scanned for potential hazards to children and these should be eliminated or appropriate controls put in place. An additional consideration relates to the supervision of children. Children should not be left unsupervised. This can become problematic if a client presents for treatment with their children with the intention of leaving their children in the waiting room during the scheduled session. In such cases, the allied health assistant or professional should discuss the potential safety issues with the client and reschedule the appointment for a time when the client can obtain supervision for their children.

WHS considerations are important and allied health assistant’s have a legal and ethical requirement to comply with all relevant procedures and requirements to promote workplace safety. Failure to take appropriate actions can leave the allied health assistant and their organisation open to civil and even criminal charges. This is why appropriate WHS documentation is also important. Allied health assistant’s must follow their organisation’s policies and procedures and complete any required documentation in relation to WHS issues (e.g., workplace checklists and critical incident reports). Critical incident reports are used to document any events or situations in which there is a risk of or actual serious harm, injury, or death to clients, workers, or others. Because of the serious nature of these situations, it is important for there to be specific policies and procedures in place for workers to follow. The extract below details one organisation’s policy and procedure for critical incidents.

| Critical Incident Report | |

|---|---|

| Policy |

Critical incidents involving services, employees or clients will be reported in accordance with procedures to ensure they are efficiently and effectively managed. This policy recognises the importance of the health, safety and well-being of clients, staff, volunteers and the public. A standard system of reporting critical incidents will enhance quality service provision and minimise the risk of harm to clients, staff, volunteers and the public. |

| Procedure |

All critical incidents must be recorded on the organisation’s Critical Incident Report and include the following actions: At the time of the incident:

Immediately after the incident:

Following the incident:

(Adapted from Community Door, n.d.a) |

In the event that an health administrator is involved in a critical incident they will be required to follow their own organisation’s policies and procedures, but this will usually involve documenting the incident in a critical incident report. Let’s have a look at an example of what that might involve.

Case Study

Hannah works at a radiologist as a health administrator. One day she is speaking with a woman at the front desk who came to have a scan following an injury. The woman appears to have a large bruise on her left arm. During their conversation, a man, the client’s partner, storms into the radiology clinic and threatens Hannah and the client with a knife. Hannah has been trained in de-escalation techniques and manages to convince the client’s partner to leave, but both she and the client are left badly shaken, and she remains concerned for her client’s safety.

Hannah knows that she needs to contact the police as per the organisation’s procedures. She also needs to arrange for a debriefing session with her supervisor and complete a critical incident report.

The critical incident report that Hannah completes is shown below.

Critical Incident Report

Date of incident: 19/11/20XX

Time of incident: 10.35pm

Location (include address where applicable): Bayside Radiology

Name of person completing form: Hannah Wilson

Position of person completing form: Medical Administrator

Contact no: 09 8765 4321

Employees/Volunteers/Management Committee members involved in incident:

1. Name: Hannah Wilson

Age: 32

Clients or community members involved in incident:

1. Name: Alesha Connor

Age: 26

Description of incident and background (relevant Information leading up to the incident, circumstances, whether the incident was witnessed and other relevant issues):

Alesha walked into the radiology clinic to undergo a scan for an injury on her arm. She has had an AVO (Apprehended Violence Order) against her partner, Ricky Marshall, since 02/11/20XX, which was shared after the incident. On the date above, Ricky entered the radiology clinic and threatened both the health administrator and Alesha with a knife for approximately 10 minutes. He subsequently left through the premises exit. The incident was not witnessed by anyone else.

Who was informed of the incident (Manager, Queensland Police, Fire Brigade)?

- Manager

- Queensland police

- __________________________________

- __________________________________

- __________________________________

Actions taken to date: (including date and time of contact that Manager and other agencies were informed, as well details of support provided):

- Police informed on 19/11/20XX at 10.55pm

- Manager informed on 19/11/20XX at 10.50pm

- Medical Administrator debriefing with manager on 19/11/201X at 11pm

- Client was provided with resources for reporting and dealing with Domestic Violence, and provided with Helpline details on 9/11/20XX at 3pm

Follow up action planned:

- __________________________________

- __________________________________

- __________________________________

- __________________________________

Critical incident report form authorised by:

H Wilson

(Signature of Employee)

Date: 19/11/20XX

Jane Thompson

(Signature of Manager)

Date: 19/11/20XX

Such reports are important because they document actions taken and are also used by management to review and improve organisational policies and procedures, to promote the continued safety of workers and clients.

Another key responsibility for a health administrator is delivering competent service. The AAPM Code of Ethical Conduct mentions several important factors that contribute to competent service delivery for health administrators.

| Ethical Conduct |

|---|

| • The sense of wholeness accompanying integrity communicates an impression of trustworthiness to others, facilitating professional relationships. • Competence in providing care, not simply the awareness or acknowledgement that are is needed, becomes an imperative. • Members of AAPM aim to facilitate autonomy, independence and self-determination in people and communities by providing appropriate resources and support in relation to their professional undertakings. • Consult other members, particularly senior and more experienced Practice Managers regarding potential conflicts of interest. (AAPM, 2023, pp. 4-14) |

While there is no specific legislation outlining legal requirements for competency, failure to provide competent service can leave a health administrator open to civil claims of negligence. Competency is defined by Queensland Health (2022), as “demonstrated capacity to apply a set of related knowledge, skills, and abilities to successfully perform a task or skill needed to satisfy the special demands or requirements of a particular situation”. To be considered competent, health administrators must meet mandatory qualification requirements (such as this Certificate) and follow relevant practice standards.

Given this, it is important for health administrators to understand the scope of practice and practice standards for health administrators (or similar roles). MAT (n.d.) enforces that it is vital for health administrator’s/medical receptionists to know what their job entails and follow procedures.

The most relevant practice standards regarding competency arise in the induction and training phase of health administrator’s role and when issues, questions, or ethical dilemmas arise (ethical dilemmas will be covered in more detail in section 3). Regarding induction and training, once you begin your work in the industry it is natural to have doubts and questions. Most workplaces will perform induction and training programs in order to help new staff become familiar with the workplace, software, duties, expectations, and standards of work, as well as relevant legislations and requirements specific to that workplace and the role. After formal induction, there are several places a new health administrator can go to for advice and answers. Position descriptions are documents that outline the specific details of the role, including tasks, responsibilities, and level of authority. Workplace policies are statements that provide clear statements of how the practice or allied health organisation conducts services. Performance reviews can also be beneficial; as is referring to relevant personnel such as co-workers, supervisors, and other health administrators. Furthermore, training may be provided throughout employment. This is often referred to as professional development and is an integral aspect of allied health professions.

It is common for roles to transform and transition as practices/organisations grow and health administrators need to be able to react to changes in each relevant field. Self-monitoring will be vital to ensure competence. MAT (n.d.) defines this process as ‘self-evaluation’, and highlights the importance of remaining flexible, open to feedback, vigilant with identifying any potential gaps in performance and expectations, and of consulting with supervisor/s to arrange training, either internally or externally, to promote skill development. All these self-development activities are considered Professional Development – which is an industry standard way for workers to improve their skills and keep up to date with industry standards and practices. As mentioned above, many allied health organisations provide ‘in house’ training to refresh skills, up-skill, or help understand changes in practice (e.g., the provision of a new service type or a change in procedure). Formal training may also occur in the form of courses, workshops, and seminars.

MAT (n.d.) outlines that if a health administrator/medical receptionist is unsure what their role entails or needs advice regarding work instructions that they should consider the following steps:

• Seek regular support and supervision from your supervisor through supervisory sessions and bring any situations to the attention of your team leader

• Seek advice from work colleagues through consultation and staff meetings

• Seek to have your position description clarified and/or have it include reference to professional standards or legislative provisions.

• Seek to have your competencies assessed and/or recognised

• Ensure that all major work activities are accurately documented/recorded

(MAT, n.d., p. 3)

Complaints Management

Another organisational consideration regarding delivering competent service involves appropriate complaints management. Allied health organisations should have policies and procedures in place for receiving and responding to client complaints. Clients have the right to make a complaint and health administrators (and their employers) are required to take these seriously and make appropriate changes where warranted. Following appropriate processes and making improvements in response to such complaints are also critical to promoting professional practice.

Health administrators can take steps to reduce the number of complaints by being open and honest regarding wait times and delays. MAT (n.d.) also suggests that health administrators can reduce the risk of escalation to complaints by remembering the three “A’s”: agree, apologise, and acknowledge.

It is important to understand that clients are also able to make a complaint to the Australian Association of Practice Management (AAPM), the Office of the Health Ombudsman, or other relevant reporting body for allied health, if they believe that a health administrator or professional has breached any specific clause/s of the Code of Ethical Conduct. If a health administrator has been found to be in breach, the AAPM can impose different sanctions depending upon the seriousness of the breach. These sanctions range from the introduction of probationary requirements and additional supervision through to the termination of membership with the AAPM.

Included in the AAPM Code of Ethical Conduct (Reading A) is the Rules and Procedures for managing complaints through AAPM (Appendix A). Through these procedures, AAPM aims to:

1. deliver an effective complaint handling system founded on the principles of fairness, accessibility, responsiveness, and efficiency.

2. ensure individuals who make a complaint are respected and aware of the process of consideration of their complaint and the outcome.

3. provide transparency around AAPM’s process for receiving, handling, and investigating complaints.

4. enable AAPM to apply lessons learnt from complaints received for continuous improvement.

(AAPM, 2023, p. 14)

Anyone who has concerns about health administrators should be directed to this code and be encouraged to read through the relevant information before contacting AAPM.

As you can see, compliance with the full range of legal and ethical requirements of allied health practice is a serious issue and one that allied health assistants must take seriously. In this section of the Study Guide you learned about a number of key allied health assistant responsibilities and the specific legal and ethical requirements underpinning these. It is important for allied health assistants to keep these legal and ethical requirements in mind in order to help develop effective practice. In the next section we will consider meeting your legal and ethical responsibilities under particular, challenging circumstances.

-

Allied Health Professionals Australia. (2023). Privacy. https://ahpa.com.au/privacy/#:~:text=AHPA%20will%20keep%20your%20personal,on%20our%20interaction%20with%20you.Australian Association of Practice Management Ltd (AAPM). (2022). Code of Ethical Conduct. 2nd Ed. https://www.aapm.org.au/Portals/1/AAPM%20Code%20of%20Ethical%20Conduct_FINAL_12OCT22.pdf

Community Door. (n.d.a) Professional boundaries. Retrieved from http://etraining.communitydoor.org.au/mod/page/view.php?id=56

Community Door. (n.d.b) Critical incident report. Retrieved from http://communitydoor.org.au/organisational-resources/administration/policies-procedures-and-templates/people-working-in-the

Corey, G., Corey, M., & Callanan, P. (2011). Issues and ethics in the helping professions. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning.

Information and Privacy Commission NSW. (2022, November). Fact sheet: A guide to retention and storage of health information in NSW for private health service providers. https://www.ipc.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-11/Fact_Sheet_A_guide_to_retention_and_storage_of_health_information_in_NSW_for_private_health_service_providers_November_2022.pdf

Kämpf, A., McSherry, B., Ogloff, J., & Rothschild, A. (2009). Confidentiality for mental health professionals: A guide to ethical and legal principles. Bowen Hills, QLD: Australian Academic Press.

Medical Administration Training (MAT). (n.d.). Roles and Responsibilities. https://mathealthclinic.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/roles-and-responsibilities-of-a-med-recept.pdf

Murphy, B. & Dillon, C. (2015). Interviewing in action in a multicultural world. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.

Network of Community Activities. (2015). Non-judgement report writing: Child protection. http://networkofcommunityactivities.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/non_judgemental_report_writing.pdf

The Compliance and Ethics Blog. (2019). [Image of cartoon outlines and corresponding relevant text relating to work safety]. https://www.complianceandethics.org/the-occupational-health-and-safety-rights-of-workers/

Training.com.au. (2020). [Image of a young man with a collared, buttoned up shirt assisting an elderly lady; both are smiling]. https://www.training.com.au/ed/6-pathways-into-community-services-career/

Welfel, E. R. (2016). Ethics in counseling and psychotherapy: standards, research and emerging issues (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Workplace Health and Safety Queensland. (2021). How to manage work health and safety risks – Code of practice (pp. 5-25). https://www.worksafe.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0022/72634/how-to-manage-work-health-and-safety-risks-cop-2021.pdf