Reading A: Making the decision in delegating and identifying tasks

Reading B: Patient-clinician communication in hospitals

Reading C: Heimlich Manoeuvre

Reading D: An overview and management of Osteoporosis

Reading E: Full Body Stretching Routine

Reading F: The Stroke Survivor

Reading G: Medical Assistance in the War Against Pathogens

Reading H: Convulsions in Children

Reading I: Population based screening framework

Important note to students

The Readings contained in this section of Readings are a collection of extracts from various books, articles and other publications. The Readings have been replicated exactly from their original source, meaning that any errors in the original document will be transferred into this Book of Readings. In addition, if a Reading originates from an American source, it will maintain its American spelling and terminology. AIPC is committed to providing you with high quality study materials and trusts that you will find these Readings beneficial and enjoyable.

Victorian State Government. (n.d.). Supervision and delegation framework for allied health assistants and the support workforce in disability.

Allied health professionals have a key role in determining whether an allied health task could be performed by an allied health assistant or disability support worker. When making this decision, the allied health professional must determine if there are mechanisms in place so that allied health assistant or disability support workers are appropriately trained, supervised and monitored to implement the task. The type, modes, frequency, and worker involved in performing and supervising the task, will often depend on a range of factors, including the nature of the delegated task, the client support needs and goals, the setting/environment, and the knowledge and skill level of the allied health assistant or disability support worker

| Decision Making Steps for Task Delegation | |

|---|---|

| Is the activity suitable to be delegated or allocated? | |

| Risk Estimation | |

Global risk

|

Disability support worker or allied health assistant level of training, skills and capability

|

| Consider the consequences of inaction | |

| Delegate or allocate task | Don't delegate or allocate task |

| Mitigate risks i.e. training, specifying environment, selecting component of task to perform, providing facilitatory aids such as video instruction |

|

| Communicate risks and mitigation i.e. document in care plans, inform line manager of risk mitigation strategies, identify triggers for review |

|

Note: The table is a framework to assist and support the allied health professional's clinical judgement.

As a part of this decision making, risks and risk mitigation strategies associated with the safe and effective performance of the task should be considered, developed, and clearly communicated to the client, line manager, organisation and allied health assistant or disability support worker. Figure 3.4 provides a flowchart to support allied health professionals to determine whether a task should be delegated to an allied health assistant or disability support worker. Figures 3.5 and 3.6 expand on the flowchart to provide a decision support framework for allied health professionals when determining the risk and nature of risk of tasks that could be delegated or identified and allocated to an allied health assistant or disability support worker. These figures can also be used to highlight risks that require the development and communication of risk mitigation strategies before delegation or identification and allocation.

A useful resource to support the decision making, Allied health professional considerations for delegation, is available at Appendix A with a word version on the department’s website at https://www.health.vic.gov.au/allied-health-workforce/allied-health-assistant-workforce

The allied health professional, when exercising their clinical judgement on the estimation of risk, should consider broader ‘global’ risk as well as the training, skills and capability of the allied health assistant or disability support worker. Global risk includes complexity of the task, environmental issues and client needs. Consideration should include the following:

- Nature of the delegated task, including:

- The complexity associated with undertaking the task.

- Characteristics of the client, including:

- The client’s support needs

- The client’s goals

- The potential impact of the task on the client – improving or declining function/status or stable function/ status.

- Characteristics related to the setting/ environment, including:

- Organisational support for allied health assistant and disability support worker performing allied health tasks

- Communication links between allied health professional, allied health assistant or disability support worker and line manager c. The setting (for example, community setting, residential service or home environment).

- The likelihood and potential consequence of injury or adverse outcome to the client, allied health assistant, disability support worker or another person.

- Once a judgement has been made around the global risk, consider how the current allied health assistant or disability support worker level of training, skills and capability impacts on this risk. Consideration should include the following:

- Qualifications and training received by the allied health assistant or disability support worker:

- a. Type of training received and evidence of skill acquisition

- b. Currency of training.

- Allied health assistant or disability support worker skills related to the task and the client:

- Familiarity with client

- Experience in conducting task

- Recentness of task performance.

- Capability and performance of the allied health assistant or disability support worker:

- Problem-solving skills and complexity of information processing

- Teamwork and communication skills, accountability for performance and values.

| Global Risk Tool | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk | Low |

|||

| Task | Simple, routine task | Simple, non- routine task | Complex, routine task | Complex, non-routine task |

| Client support needs and goals | Goals related to assistance with ADLs and/ or social and community participation - no change expected | Goals related to assistance with ADLs and/or social and community participation - monitoring for and preventing decline | Goals related to capacity building - small to medium change expected | Goals related to capacity building - substantial change expected |

| Low intensity of support need | Medium intensity of support need | High intensity of support need | ||

| Environmental support for worker delivering the task | Strong and clear communication links between coordinator, line manager, allied health professional and disability support worker | Strong communication links between coordinator, line manager, allied health professional and disability support worker | Inconsistent communication links between coordinator, line manager, allied health professional and disability support worker | |

| Regular staff and stable location | Regular staff and unstable location (i.e. respite) | Irregular staff and stable location | Irregular staff and unstable location | |

| Established organisational support | Variable organisational support | Irregular organisational support | ||

| Outcome consequence | Rare occurrence; Minimal consequence | Likely occurrence; Minimal consequence | Rare occurrence; Major consequence | Likely occurrence; Major consequence |

Legend:

|

||||

Note: This table is a decision support tool to assist and support the allied health professional's judgement in regard to risk.

| Assessment Tool - Allied Health Assistant or Disability Support Worker Level of Training, Skills and Capability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk | Low |

|||

| Training | Training with assessment received: task and client specific | Training received: task and client specific | Training received: task specific | Limited training |

| Recent training and/or skill review | Past training | Limited training | ||

| Skills for the task and client | Recent experience in conducting task | Past experience in carrying out task | Experience in carrying out similar tasks | No prior experience |

| Familiar with client | Unfamiliar with client | |||

| Task frequently conducted | Task occasionally conducted | Task not previously conducted | ||

| Capability and performance | Strong problem solving and complex information processing | Good problem solving and complex information processing | Developing problem solving and complex information processing | Basic problem solving and complex information processing |

| Strong team work, communication, accountability and values | Good team work, communication, accountability and values | Developing team work, communication, accountability and values | Basic team work, communication, accountability and values | |

Note: This table is a decision support tool to assist and support the allied health professional's judgement in regard to risk.

Consequences of inaction

The allied health professional should consider the potential outcome for the client if a task is not allocated or delegated to an allied health assistant or disability support worker. This may be in relation to available funding for allied health tasks, client’s request, goals and needs. However, all tasks delegated or allocated should have risk and risk mitigation plans, whether informal or formal, with clear and accessible communication and documentation. Where the decision is made not to proceed, it is necessary to clearly document this. If delegation of tasks is deemed best practice, however environmental factors prevent this, based on the decision-making factors involved, recommendations for resolution should be provided to the client, decision maker, support coordinator, line manager or through NDIS planning processes. Dignity of risk recognises that people should be able to do something that involves a level of risk, ensuring that they are empowered to make their own choices, understand, and live with the consequences.

Case Study: Shared decision making

Greg really enjoys pizza; however, he often coughs when trying to eat it. Greg has requested a speech pathologist to review his swallowing ability. The speech pathologist assesses Greg’s swallowing and identifies a risk that Greg will choke if he continues to eat pizza. Therefore, the speech pathologist recommends Greg doesn’t eat pizza. Considering the risks outlined by the speech pathologist, Greg decides he would still like to eat pizza. The speech pathologist, using risk mitigation tools and clinical judgment, informs Greg of the risks associated with eating pizza and possible risk minimisation strategies. The speech pathologist, in consultation with Greg, develops a risk management plan, including a list of strategies to reduce the risk of aspirating and what to do if this occurred. Greg approves the risk plan. He is able to make an informed decision and, with the speech pathologist’s support, decides to only eat pizza at the times he is most alert and is sitting well supported in his wheelchair. Greg has previously been assessed as competent to make this decision by his general practitioner. This discussion, the Greg’s informed decision and the risk mitigation strategies are documented.

Australian Commission. (2016). Patient-clinician communication in hospitals: Communicating for safety at transitions of care. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/Information-sheet-for-healthcare-providers-Improving-patient-clinician-communication.pdf

Why is this important?

Effective communication and the accurate transfer of information between you and the person in your care are essential to ensuring safe patient care.

Communication errors are a major contributing factor in hospital sentinel events.1 At transitions of care there is an increased risk of communication errors occurring. This can lead to poor health outcomes, distress, or inappropriate patient care.2, 3 Effective patient-clinician communication is a core clinical skill. How you communicate with a patient can profoundly impact their care experience and how they manage their health when they leave your care.4, 5 This information sheet outlines strategies and actions that you may find helpful when communicating with patients at transitions of care

Inpatient care transitions are about involving the patient from day one, being open and transparent, setting goals, reality checks about where we've got to, and having a key 'go to' person so there's always someone the patient can interact with in terms of the evolution of their discharge plan. It's the go-to backwards and forwards.

-Gerontologist-

What is my role?

You play an important role in determining whether effective communication with the person you are caring for takes place. When a person seeks treatment or care, it can be a daunting and stressful experience, regardless of their knowledge or familiarity with the health system. This anxiety can increase when a person’s care is transferred or there is a change in their care, and they are unsure or do not understand what is happening or going to happen next. Open, honest, respectful and tailored communication can help you reduce their anxiety. By effectively communicating with patients, families and their carers you can build a shared understanding about goals, expectations and preferences.

Patient participation as a continuum - a person’s willingness to participate in communication about their care can vary.

At one end there is the activated patient who plays a key role in communication processes and assumes responsibility for initiating contact and communication with their healthcare providers. At the other end there is the passive patient, who chooses to have their healthcare providers lead all aspects of the interaction and communication. To respect a person’s choice, it is important to recognise that willingness and ability to participate is influenced by a range of factors and may change throughout the episode of care. A key element of ensuring that you meet a patient’s needs is to regularly review and check-in with them, or their family and carer, about whether they would like to participate in communication. Consideration of health literacy, language barriers and culture will be important

| What Are the Essential Elements of Effective Patient-Clinician Communication? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Element | Purpose | Outcome |

| Fostering relationships |

|

|

| Two-way exchange of information |

|

|

| Conveying empathy |

|

|

| Engaging patients in decision- making and care planning |

|

|

| Managing uncertainty and complexity |

|

|

What can I do?

Actions and strategies that may help you improve patient-clinician communication are provided for three key transition points:

- when you first engage with a patient

- when you are transferring care to another provider

- when you discharge a patient.

It is recognised that these transitions do not occur in isolation of one another, and that some strategies and actions will be relevant at all transition points. Coordination and communication between you, the patient, their family and carer, and other healthcare providers across all these points is essential to ensuring safe, continuous care.

When you first engage with a patient: Why is this important?

To ensure you have all the relevant information you need to help inform your clinical assessment, and that decisions about care are appropriate and reflect the patient’s needs and preferences.

Strategies and actions to engage with a patient include:

- Introducing yourself in a personal manner.

- Determining if the patient needs assistance to communicate. Consider their health literacy, language barriers and cultural and religious background.

- Taking steps to overcome any communication barriers, including having an interpreter or family member present; avoiding jargon or complex medical terms; and using language that the patient can understand.

- Directing your communications to the patient, even if there is an interpreter, family member or carer present.

- Asking the patient if they have any concerns about sharing their information with their family or carer.

- Inviting the patient to participate in their care, let them know they are welcome to ask questions or raise concerns.

- Asking the patient if they have an advanced care plan in place.

- Discussing with the patient their goals of care, including what is realistic and possible, and how this will be incorporated into their care plan.

- Taking into consideration family and carer concerns and their provision of information.

- Documenting patient preferences, expectations and goals of care in their care plan.

When you are transferring care to another provider: Why is this important?

To ensure that any information transferred is up to date, accurate and reflects the patient’s needs and preferences. It can also help you address any concerns and manage any uncertainty or distress they may have about changes to their care. Strategies and actions to engage with a patient include:

- Requesting permission from the patient before doing anything to or for them.

- Describing the roles of each person in the care team.

- Letting the patient know who is responsible for their care at any point in time, and keeping them informed about their care plan.

- Inviting the patient to participate in their transition of care; let them know they are welcome to ask questions or raise concerns.

- When possible, and if they choose to, involving the patient’s family and carer in transition communications and communication about their care.

- Letting the patient know about any expected transitions of care, why they are happening and approximate timeframes (e.g., shift changes, moving wards, or going for a test or procedure).

- Re-checking the patient’s needs, preferences and goals and allow them time to tell you of any changes, concerns, or questions about their care.

- Acknowledging their pain, discomfort, or distress, when appropriate.

- Notifying the family and carer of any moves and/or changes to the patient’s care or health status.

When you discharge a patient: Why is this important?

To ensure that the patient, and their family and carer, understands how to manage their care when they leave and any next steps they need to take.

Strategies and actions to engage with a patient include:

- Providing the patient (and their family and carer, if they choose) with a discharge summary and explain the key elements of the summary. This includes: - their role in looking after their health once they leave - their treatment plan and current medicine list - any follow-up plans for outstanding tests and/or appointments - what they may need to discuss with their GP - if they are being transferred to another service, what to expect at the next site of care - warning symptoms or signs to look out for, and the name and phone number of who to contact if this occurs.

- Checking the patient understands and encouraging them to ask questions or raise concerns (e.g. you could ask them to repeat instructions).

- Checking the patient’s willingness and ability to follow the plan.

- Encouraging the patient, their family and carer to provide feedback about their care experience.

- Completing a post discharge follow-up phone call, where appropriate

Examples of other strategies and tools

TOP 5

A communication tool that focuses on clinician-carer communication. Developed in conjunction with carers by the Central Coast Local Health District and implemented in selected hospitals across NSW by the Clinical Excellence Commission.

Clinical staff engage in a structured process to communicate with carers. The purpose is to gain and record up to five important non-clinical tips and management strategies for personalising care.

Talk to the carer

Obtain the information

Personalise the care

5 non-clinical tips and management strategies for personalising care developed by clinical staff and carers.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ): Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program.

Includes a patient and family engagement module. The AHRQ in the United States has made available their Comprehensive Unit-based Safety Program, which includes a patient and family engagement module.

The module focuses on making sure patients and family members understand what is happening during the patient’s hospital stay, can become active participants in their care and are prepared for discharge.

AIDET A tool used to assist with patient-clinician communication.

This tool has been used across a number of different clinical settings.

Acknowledge: Greet patients through eye contact, smile and a hello. Make them feel important.

Introduce yourself by name and your position. Describe what you are going to do and your part in the process. Listen to the patient’s responses.

Duration: Estimate the time to complete the procedure, any waiting that may be involved and update the patient if the timing changes.

Explain: what you are going to do to or for the patient. Ask if the patient has any concerns or questions before progressing.

Thank you: Thank the patient for their cooperation / involvement.

Habrat, D. (2022). How to do the Heimlich Manoeuvre in the conscious adult of child. Merck & Co.

The Heimlich manoeuvre (abdominal thrusts) is a rapid first-aid procedure to treat choking due to upper airway obstruction by a foreign object, typically food or a toy. Chest thrusts and back blows can also be used if needed.

Indications for a Heimlich Manoeuvre

- Choking due to severe upper airway obstruction due to a foreign object (signalled by inability to speak, cough, or breathe adequately)

The Heimlich and other manoeuvres should be used only when the airway obstruction is severe, and life is endangered. If the choking person can speak, cough forcefully, or breathe adequately, no intervention is required.

Contradictions to Heimlich Manoeuvre

Absolute contraindications

- Age < 1 year is a contraindication to the Heimlich manoeuvre

Relative contraindications

- Children < 20 kg (45 lb; typically, < 5 years) should receive only moderate pressure thrusts and back blows.

- Obese patients and women in late pregnancy should receive chest thrusts instead of abdominal thrusts.

Complications of Heimlich Manoeuvre

- Rib injury or fracture

- Internal organ injury

Additional considerations for Heimlich manoeuvre

- These rapid first aid procedures are done immediately wherever the person is choking.

- Use of significant, abrupt force is appropriate for these manoeuvres. However, clinical judgment is needed to avoid excessive forces that can cause injury.

- The Heimlich manoeuvre is well-known and widely used. However, chest thrusts and back blows may produce higher airway pressures. More than one manoeuvre may be used in succession if the initial manoeuvre fails to remove the obstructing object.

Relevant Anatomy for Heimlich Manoeuvre

- The epiglottis usually protects the airway from aspiration of foreign objects (e.g., food).

- Aspirated objects may be above or below the vocal cords.

Positioning for Heimlich Manoeuvre

- In general, the rescuer stands behind the choking person or kneels behind a child.

Step-by-Step Description of Heimlich Manoeuvre

Determine if there is severe airway obstruction

- Look for signs such as inability to speak, cough, or breathe adequately.

- Look for hands clutching the throat, which is the universal distress signal of severe airway obstruction.

- Ask: “Are you choking?”

- If the person can speak and breathe, encourage them to cough but do not initiate airway clearance manoeuvres; instead, arrange medical evaluation.

- If the choking person nods yes or cannot speak, cough, or breathe adequately, that suggests severe airway obstruction and the need for airway clearance manoeuvres.

Treat the choking conscious adult or child

- Stand directly behind the choking adult or kneel behind a child.

- Begin with abdominal thrusts for people who are not pregnant or obese; do chest thrusts for obese patients and women in late pregnancy.

- Alternate between sets of abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuverer), chest thrusts, and back blows as needed to relieve the obstruction.

- Continue until obstruction is removed or advanced airway management is available.

- If the person loses consciousness, start cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). After each set of chest compressions, look inside the patient's mouth before giving rescue breaths and remove any visible obstruction that can be reached. Do not do blind finger sweeps.

Abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuverer):

- Encircle the patient’s midsection with your arms.

- Clench one fist and place it midway between the umbilicus and xiphoid.

- Grab the fist with the other hand (see figure Abdominal thrusts with victim standing or sitting).

- Deliver a firm inward and upward thrust by pulling with both arms sharply backward and upward.

- Rapidly repeat the thrust 6 to 10 times as needed.

Abdominal thrusts with victim standing or sitting (conscious)

Chest thrusts:

- Encircle the patient’s midsection with your arms.

- Clench one fist and place it on the lower half of the sternum.

- Grab the fist with the other hand.

- Deliver a firm inward thrust by pulling both arms sharply backward.

- Rapidly repeat the thrust 6 to 10 times as needed.

Back blows:

- Wrap one arm around the waist to support the patient's upper body; small children can be laid across your legs.

- Lean the person forward at the waist, about 90 degrees if possible.

- Using the heel of your other hand, rapidly deliver 5 firm blows between the person's shoulder blades.

Aftercare for Heimlich Manoeuvre

- Patients with any symptoms remaining after foreign body removal should have a medical evaluation.

Warnings and Common Errors for Heimlich Manoeuvre

- These manoeuvres should not be done if the choking person can speak, cough forcefully, or breathe adequately.

- In obese patients and women in late pregnancy, chest thrusts are used instead of abdominal thrusts.

Tips and Tricks for Heimlich Manoeuvre

- The Heimlich maneuverer may induce vomiting. Although vomiting may assist in dislodging a tracheal foreign body, it does not necessarily mean that the airway has been cleared

Sozen, T., Ozisik, L., & Basaran, C. N. (2017). An overview and management of osteoporosis. European Journal of Rheumatology.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a disease that is characterized by low bone mass, deterioration of bone tissue, and disruption of bone microarchitecture: it can lead to compromised bone strength and an increase in the risk of fractures. Osteoporosis is the most common bone disease in humans, representing a major public health problem. It is more common in Caucasians, women, and older people. Osteoporosis is a risk factor for fracture just as hypertension is for stroke. Osteoporosis affects an enormous number of people, of both sexes and all races, and its prevalence will increase as the population ages. It is a silent disease until fractures occur, which causes important secondary health problems and even death. It was estimated that the number of patients worldwide with osteoporotic hip fractures is more than 200 million. It was reported that in both Europe and the United States, 30% women are osteoporotic, and it was estimated that 40% post-menopausal women and 30% men will experience an osteoporotic fracture in the rest of their lives.

Osteoporosis is also an important health issue in Turkey, because the number of older people is increasing. The incidence rate for hip fracture increases exponentially with age in all countries as well as in Turkey, which is evident in the FRACTURK study. It was estimated that around the age of 50 years, the probability of having a hip fracture in the remaining lifetime was 3.5% in men and 14.6% in women. Bone tissue is continuously lost by resorption and rebuilt by formation; bone loss occurs if the resorption rate is more than the formation rate. The bone mass is modelled (grows and takes its final shape) from birth to adulthood: bone mass reaches its peak (referred to as peak bone mass (PBM)) at puberty; subsequently, the loss of bone mass starts. PBM is largely determined by genetic factors, health during growth, nutrition, endocrine status, gender, and physical activity. Bone remodelling, which involves the removal of older bone to replace with new bone, is used to repair microfractures and prevent them from becoming macro fractures, thereby assisting in maintaining a healthy skeleton. Menopause and advancing age cause an imbalance between resorption and formation rates (resorption becomes higher than absorption), thereby increasing the risk of fracture.

Certain factors that increase resorption more than formation also induce bone loss, revealing the microarchitecture. Individual trabecular plates of bone are lost, leaving an architecturally weakened structure with significantly reduced mass; this leads to an increased risk of fracture that is aggravated by other aging-associated declines in functioning. Increasing evidence suggests that rapid bone remodelling (as measured by biochemical markers of bone resorption or formation) increases bone fragility and risk of fracture. There are factors associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis-related fractures. These include general factors that relate to aging and sex steroid deficiency, as well as specific risk factors such as use of glucocorticoids (which cause decreased bone formation and bone loss), reduced bone quality, and disruption of microarchitectural integrity. Fractures result when weakened bone is overloaded, often by falls or certain daily chores.

Clinical Consequences

Clinical evaluation Osteoporosis has been mislabelled as a women’s disease by the public, but it affects men, too: young men are afflicted by it, which usually goes undiagnosed until a fracture brings the patient to a doctor. However, delayed interventions are usually unsuccessful. The diagnosis of osteoporosis is never taken as primary osteoporosis without ruling out the secondary causes. A good history and physical examination of the patient always reveal certain clues about the presence of another disease: certain special laboratory evaluations might be needed to rule out other responsible diseases.

Approach to a patient with osteoporosis

A detailed history and physical examination together with BMD assessment, vertebral imaging to diagnose vertebral fractures (when appropriate), and the WHO-defined 10-year estimated fracture probability test are utilized to establish an individual patient’s fracture risk (30). All postmenopausal women and men aged 50 years and above should be evaluated for osteoporosis risk in order to determine the need for BMD testing and/or vertebral imaging.

In general, the more the risk factors, larger is the risk of fracture. Osteoporosis is preventable and treatable, but because there are no warning signs prior to a fracture, many people are not being diagnosed in time to receive effective therapy during the early phase of this disease. Universal recommendations for all patients Several interventions, including an adequate intake of calcium and V-D, are fundamental aspects for any osteoporosis prevention or treatment program, including lifelong regular weight-bearing and muscle-strengthening exercises, cessation of tobacco use and excess alcohol intake, and treatment of risk factors for falling. In order to maintain serum calcium at a constant level, an external supply of adequate calcium is necessary; otherwise, low serum calcium levels promote bone resorption to bring the calcium levels to normal. Calcium requirements increase among older persons; thus, the older population is particularly susceptible to calcium deficiency. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) recommends a daily intake of 1000 mg/ day for men aged 50–70 years and 1200 mg of calcium for women aged over 50 years and men aged over 70 years. All calcium preparations are better absorbed when taken with food, particularly in the absence of the secretion of gastric acid. For optimal absorption, the amount of calcium should not exceed 500–600 mg per dose. Calcium carbonate is the least expensive and necessitates the use of the fewest number of tablets, but it may cause gastrointestinal (GI) complaints. Calcium citrate is more expensive, and a larger number of tablets are needed to achieve the desired dose; however, its absorption is not dependent on gastric acid, and it does not cause GI complaints. Some food products contain excess oxalate, which prevents absorption of calcium by binding with it. Intakes in excess of 1200-1500 mg/ day may increase the risk of developing kidney stones, cardiovascular diseases, and strokes. Vitamin D is necessary for calcium absorption, bone health, muscle performance, and balance. The IOM recommends a dose of 600 IU/ day until the age of 70 years in adults and 800 IU/day thereafter.

Chief dietary sources of V-D include V-D–fortified milk, juices and cereals, saltwater fish, and liver. Supplementation with V-D2 (ergocalciferol) or V-D3 (cholecalciferol) may be used. Many older patients are at a high risk for V-D deficiency, which include the following: patients with malabsorption issues (e.g., celiac disease) or other intestinal diseases (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, gastric bypass surgery); gastric acidity; pernicious anaemia; proton pump inhibitors; chronic renal or liver insufficiency; patients on medications that increase the breakdown of V-D (e.g., some anticonvulsive drugs); or glucocorticoids, which decrease calcium absorption; housebound and chronically ill patients; persons with limited sun exposure; individuals with very dark skin; and obese individuals. Serum 25 (OH) D levels should be measured in patients at the risk of V-D deficiency. V-D supplements should be recommended in amounts sufficient to bring the serum 25 (OH) D level to approximately 30 ng/mL (75 nmol/L). Many patients with osteoporosis will need more than the general recommendation of 800-1000 IU/day. The safe upper limit for V-D intake for the general adult population was increased to 4000 IU/day in 2010.

Alcohol

Excessive intake of alcohol has detrimental effects on bones, so it should be avoided. The mechanisms are multifactorial and include predisposition to falls, calcium deficiency, and chronic liver disease, which, in turn, results in predisposition toward V-D deficiency. Persons predisposed toward osteoporosis should be advised against consuming more than 7 drinks/ week, 1 drink being equivalent to 120 mL of wine, 30 mL of liquor, or 260 mL of beer. Caffeine: Patients should be advised to limit their caffeine intake to less than 1 to 2 servings (8 to 12 ounces in each serving) of caffeinated drinks per day. Some studies showed that there is a relationship between caffeine consumption and fracture risk.

Exercise

A regular weight-bearing exercise regimen (for example, walking 30-40 min per session) along with back and posture exercises for a few minutes on most days of the week should be advocated throughout life. Children and young adults who are active reach a higher peak bone mass than those who are not. Among older patients, these exercises help slow bone loss attributable to disuse, improve balance, and increase muscle strength, ultimately reducing the risk of falls. Patients should avoid forward flexion, side-bending exercises, or lifting heavy objects because pushing, pulling, lifting, and bending activities compress the spine, leading to fractures.

Conclusion

Osteoporosis is a common and silent disease until it is complicated by fractures that become common. It was estimated that 50% women and 20% of men over the age of 50 years will have an osteoporosis-related fracture in their remaining life. These fractures are responsible for lasting disability, impaired quality of life, and increased mortality, with enormous medical and heavy personnel burden on both the patient’s and nation’s economy. Osteoporosis can be diagnosed and prevented with effective treatments before fractures occur. Therefore, the prevention, detection, and treatment of osteoporosis should be a mandate of primary healthcare providers.

Healthline. (2020, September 18). How to do a full body stretching routine. https://www.healthline.com/health/full-body-stretch

Professional sprinters sometimes spend an hour warming up for a race that lasts about 10 seconds. In fact, it’s common for many athletes to perform dynamic stretches in their warmup and static stretches in their cooldown to help keep their muscles healthy.

Even if you’re not an athlete, including stretches in your daily routine has many benefits. Not only can stretching help you avoid injuries, it may also help slow down age-related mobility loss and improve circulation. Let’s take a closer look at the numerous benefits of full-body stretching and how to build a stretching routine that targets all your major muscle groups.

What are the benefits of stretching?

Stretching regularly can have benefits for both your mental and physical health. Some of the key benefits include:

- Decreased injury risk. Regular stretching may help reduce your risk of joint and muscle injuries.

- Improved athletic performance. Focusing on dynamic stretches before exercising may improve your athletic performance by reducing joint restrictions, according to a 2018 scientific review.

- Improved circulation. A 2015 study of 16 men found that a 4-week static stretching program improved their blood vessel function.

- Increased range of motion. A 2019 study of 24 young adults found that both static and dynamic stretching can improve your range of motion.

- Less pain. A 2015 study on 88 university students found that an 8-week stretching and strengthening routine was able to significantly reduce pain caused by poor posture.

- Relaxation. Many people find that stretching with deep and slow breathing helps promote feelings of relaxation.

When to stretch

There are many ways to stretch, and some types of stretches are better at certain times. Two common types of stretches include:

- Dynamic stretches. Dynamic stretching involves actively moving a joint or muscle through its full range of motion. This helps get your muscles warmed up and ready for exercise. Examples of dynamic stretches include arm circles and leg swings.

- Static stretches. Static stretching involves stretches that you hold in place for at least 15 seconds or longer without moving. This helps your muscles loosen up, especially after exercise.

Before exercise

Warm muscles tend to perform better than cold muscles. It’s important to include stretching in your warmup routine so you can get your muscles ready for the upcoming activity.

Although it’s still a topic of debate, there’s evidence that static stretching before exercise can reduce power and strength output in athletes.

If you’re training for a power or speed-based sport, you may want to avoid static stretching in your warmup and opt for dynamic stretching instead.

After exercise

Including static stretching after your workout may help reduce muscle soreness Trusted Source caused by strenuous exercise. It’s a good idea to stretch all parts of your body, with an emphasis on the muscles you used during your workout.

After sitting and before bed

Static stretching activates your parasympathetic nervous system, according to a 2014 study of 20 young adult males.

Your parasympathetic nervous system is responsible for your body’s rest and digestive functions. This may be why many people find stretching before bed helps them relax and de-stress at the end of the day. Stretching after a period of prolonged inactivity can help increase blood flow to your muscles and reduce stiffness. This is why it feels good — and is beneficial — to stretch after waking up or after sitting for a long period of time.

How to do a full-body stretching routine

When putting together a full-body stretching routine, aim to include at least one stretch for each major muscle group in your body.

You may find that certain muscles feel particularly stiff and need extra attention. For example, people who sit a lot often have tight muscles in their neck, hips, legs, and upper back.

To target particularly stiff areas, you can:

- perform multiple stretches for that muscle group

- hold the stretch longer

- perform the stretch more than once

Calf stretch

- Muscles stretched: calves

- When to perform: after running or any time you have tight calves

- Safety tip: Stop immediately if you feel pain in your Achilles tendon, where your calf attaches to your ankle.

How to do this stretch:

- Stand with your hands against the back of a chair or on a wall.

- Stagger your feet, one in front of the other. Keep your back leg straight, your front knee slightly bent, and both feet flat on the ground.

- Keeping your back knee straight and back your foot flat on the ground, bend your front knee to lean toward the chair or wall. Do this until you feel a gentle stretch in the calf of your back leg.

- Hold the stretch for about 30 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

Leg swings

- Muscles stretched: hips, inner thigh, glutes

- When to perform: before a workout

- Safety tip: Start with smaller swings and make each swing bigger as your muscles loosen.

How to do this stretch:

- Stand with your feet shoulder-width apart.

- Balancing on your left leg, swing your right leg back and forth in front of your body, only going as far as is comfortable.

- Perform 20 reps.

- Repeat on the other side.

Hamstring stretch

- Muscles stretched: hamstring, lower back

- When to perform: after your workout, before bed, or when your hamstrings are tight

- Safety tip: If you can’t touch your toes, try resting your hands on the ground or on your leg instead.

How to do this stretch:

- Sit on a soft surface, with one leg straight out in front of you. Place your opposite foot against the inner thigh of your straight leg.

- While keeping your back straight, lean forward and reach for your toes.

- When you feel a stretch in the back of your extended leg, hold for 30 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

Standing quadriceps stretch

- Muscles stretched: quadriceps

- When to perform after running or whenever your thighs feel tight

- Safety tip: Aim for a gentle stretch; overstretching can cause your muscles to become tighter.

How to do this stretch:

- Stand upright and pull your right foot to your butt, holding it there with your right hand.

- Keep your knee pointing downward and your pelvis tucked under your hips throughout the stretch.

- Hold for 30 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

Glute stretch

- Muscles stretched: glutes, hips

- When to perform: after running or before bed

- Safety tip: Stop if you feel pain in your knees, hips, or anywhere else.

How to do this stretch:

- Lie on your back with your legs up and your knees bent at a 90-degree angle.

- Cross your left ankle over your right knee.

- Grab your right leg (either over or behind your knee) and pull it toward your face until you feel a stretch in your opposite hip.

- Hold for 30 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

Upper back stretch

- Muscles stretched: back, shoulders, neck

- When to perform: after prolonged sitting or whenever your back is stiff

- Safety tip: Try to stretch both sides equally. Don’t force the stretch beyond what’s comfortable.

How to do this stretch:

- Sit in a chair with your back straight, core engaged, and ankles in line with your knees.

- Twist your body to the right by pushing against the right side of the chair with your left hand.

- Hold for 30 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

Chest stretch

- Muscles stretched: chest, biceps, shoulders

- When to perform: after long periods of sitting

- Safety tip: Stop immediately if you feel discomfort in your shoulder.

How to do this stretch:

- Stand in an open doorway and place your forearms vertically on the doorframe.

- Lean forward until you feel a stretch through your chest.

- Hold the stretch for 30 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

Neck circles

- Muscles stretched: neck

- When to perform after sitting or whenever your neck feels tight

- Safety tip: It’s normal to have one side that feels tighter than the other. Try holding the stretch longer on the side that feels tighter.

How to do this stretch:

- Drop your chin toward your chest.

- Tilt your head to the left until you feel a stretch along the right side of your neck.

- Hold for 30 to 60 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

The bottom line

Stretching regularly can:

- improve your range of motion

- reduce your risk of injury

- improve circulation

- boost athletic performance

If you’re looking to create a full body stretching routine, try to choose at least one stretch that targets each major muscle group.

The stretches covered in this article are a good start, but there are many other stretches you can add to your routine. If you have an injury or want to know what kinds of stretches may work best for you, be sure to talk with a certified personal trainer or physical therapist.

McCann, A. (2006). Stroke survivor: A personal guide to coping and recovery. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

A physiological warning of stroke – transient ischaemic attack

The most common warning sign of stroke is the transient ischaemic attack (TIA). A TIA is often referred to as a ‘mini-stroke’, and is a short period of disturbance of body function, lasting for less than 24 hours, resulting from a temporary reduction in blood supply to part of the brain. Depending on the area of the brain affected by a TIA, the sufferer can have a temporary loss of limb sensation or strength, a loss of vision, or even a loss of consciousness. A TIA commonly lasts between two and 15 minutes, and having been rapid in its onset leaves no persistent neurological deficit. However, TIAs must always be taken seriously no matter how quickly they pass, as they are a clear warning that a life-threatening stroke may occur soon.

TIAs should always be investigated, the cause should be found and, if possible, treated. Without treatment, about one in four people who have had a TIA will have a stroke within the next few years. It is therefore quite clear that each and every TIA should be taken seriously, by both the individual concerned and those members of the medical profession he or she presents to. It is not too late to seek medical attention or advice even when the symptoms have gone away.

The important emphasis in terms of identifying the cause of a stroke is that, if at all possible, it should be done before the stroke happens, in a proactive, preventative way, and not afterwards in a reactive, rehabilitative way. However, until the general population take some responsibility for themselves, scientists are still trying to develop and improve risk-score methods to predict, and aim to prevent, a stroke. The Oxford Stroke Prevention Research Unit has identified four factors that could predict the future risk of a stroke if an individual suffers and reports a TIA. These are:

- The Age of the individual

- The Blood pressure of the individual

- The Clinical features (i.e., the symptoms) the individual presents

- The Duration of the TIA.

Simply speaking, by translating these facts to create an ABCD score, the high-risk individuals, who may need emergency treatment, can be identified. The majority of TIAs are the result of arterial or cardiac thromboses, but they may equally be associated with high blood pressure, smoking, obesity, high cholesterol levels, or a combination of all of these.

The onset of stroke. The primary identifying feature of stroke is its acute and sudden onset. In other words, the symptoms of stroke happen immediately. In rare cases, these symptoms of a stroke can be difficult to attribute to a stroke with any certainty, even for doctors. However, this is not usually the case, and a failure to identify the symptoms of a stroke in another is really the result of poor education or ignorance caused by complacency. In a 1996 Gallup survey conducted for the National Stroke Association, 17 per cent of adults over age 50 were unable to name a single stroke symptom. Unfortunately, such a lack of awareness can spell disaster. The stroke victim may suffer significant brain damage when people nearby fail to recognise the symptoms of a stroke.

As I have discussed, each part of the brain has more than one specific function and each part of the brain can be subject to a stroke. As a result, the general and most common symptoms of stroke include:

- numbness or weakness in the face, arms or legs (especially on one side of the body)

- confusion, difficulty speaking or understanding speech

- vision disturbances in one or both eyes

- dizziness

- some trouble walking

- a loss of balance or co-ordination

- a severe headache with no known cause.

While the symptoms may be inconsistent, depending on the area of the brain affected by the interruption in normal blood flow, there can be no doubt of the following – the longer blood flow is cut off to the brain, the greater the potential for permanent damage to the brain. Within a few minutes of the onset of a stroke, the area of the brain affected is damaged, some of it beyond repair.

Any observer can recognise a possible stroke by asking the following three simple questions of the person suffering:

- Can you raise your arms and keep them up?

- Can you smile?

- Can you repeat a simple sentence?

If the answer to one or more of these questions is ‘no’, then immediate medical attention should be sought. If the individual in distress has in fact had a stroke, the full and lasting effects, as I have said, will be dependent upon the area of the brain affected and the speed with which medical attention is given.

Why stroke occurs

I have mentioned previously that a stroke occurs when a blood clot blocks a blood vessel or artery, or when a blood vessel breaks, interrupting blood flow to an area of the brain. It most often occurs when the carotid arteries become blocked, and the brain does not get enough oxygen. The physical damage depends upon which blood vessel is damaged and whether the damage was due to blockage or haemorrhage.

Stroke caused by a blockage or clot – ischemia

In everyday life, blood clotting is most beneficial. When an individual bleeds from a wound, blood clots work to slow and eventually stop the bleeding. In the case of a stroke, however, blood clots are dangerous because they can block arteries and cut off blood flow. Ischaemic strokes can happen as the result of unhealthy blood vessels, which are clogged with a build-up of fatty deposits and cholesterol. This condition is known as ‘atherosclerosis’. The body regards atherosclerosis as multiple, tiny and repeated injuries to the blood vessel wall. It then reacts to these injuries just as if it was bleeding from a wound, and it responds by forming clots. Atherosclerosis is often associated with stroke and the supply of blood to the brain, and is the progressive narrowing and hardening of arteries over time. It is known to occur with ageing, but other factors include high cholesterol, high blood pressure, smoking, diabetes and a family history of atherosclerotic disease. Other causes of ischaemic stroke include use of street drugs, traumatic injury to the blood vessels of the neck, or disorders of blood clotting.

Approximately 80 per cent of all strokes are ischaemic. Due to the contributory factors of ischaemic stroke mentioned above, many people who suffer them are older (60 or more years old), and the risk of ischaemic stroke increases with age. As I clarified earlier, an ischaemic stroke can occur in two ways, and will then often be classified as an ‘embolic’ or a ‘thrombotic’ stroke.

Embolic stroke

With an embolic stroke, a blood clot forms somewhere in the body and then moves. This kind of blockage causing a stroke is called a ‘cerebral embolism’. While it may form in the arteries of the chest and neck, a part may break off before travelling through the bloodstream to the brain. Alternatively, it may possibly form in the heart, but again a part may break off and travel to the brain.

Once in the brain, the clot eventually travels through the system until it reaches a blood vessel small enough to block its passage. When it can travel no further, the clot lodges there blocking the blood vessel and causing a stroke.

Thrombotic stroke

In the case of a thrombotic stroke, blood flow is impaired because of a blockage that has built up in one or more of the arteries supplying blood to the brain, most often in the large arteries, such as the carotid artery or middle cerebral artery. A significant number of strokes are caused by blockages and narrowing of the carotid arteries and carotid artery disease increases the risk for stroke in three ways:

- through fatty deposits (cholesterol or plaque) building up and severely narrowing the carotid arteries

- by a blood clot becoming stuck in a carotid artery, which has already been narrowed by plaque

- by plaque breaking off from the carotid arteries and in so doing blocking one of the smaller arteries in the brain (cerebral artery).

Generally speaking, if a carotid artery is blocked then a cerebral stroke will result. If a vertebral artery is blocked, then a cerebellar or brainstem stroke will result. The process leading to this blockage is what is known as thrombosis, and there are two types of thrombosis which can cause a stroke – large vessel thrombosis and small vessel disease. Large vessel thrombosis is the most common, and probably the most understood type of thrombotic stroke. Most large vessel thrombosis is caused by a combination of long-term atherosclerosis, followed by a rapid blood clot formation. It is common that thrombotic stroke patients are also likely to have coronary artery disease, and actually a heart attack is a frequent cause of death in patients who have suffered this type of stroke.

Small vessel disease (also called lacunar infarction) occurs when the blood flow is blocked to a very small, but often a deep, penetrating, arterial vessel. Very little is known about the causes of small vessel disease, but it seems to be very closely linked to hypertension.

Stroke caused by bleeding – haemorrhage

In the case of a haemorrhagic stroke, which accounts for the remaining 20 per cent of strokes after ischaemic strokes, it is, as I have already said, the breakage of a blood vessel in the brain that leads to bleeding. The bleeding then irritates the brain tissue and causes swelling (known as cerebral oedema). The surrounding tissues of the brain resist the bleeding, which can be contained by forming a mass (haematoma). Both swelling and haematoma will compress and displace normal brain tissue causing damage. Haemorrhages can be caused by a number of disorders, which affect the blood vessels, including long-standing hypertension (high blood pressure), high cholesterol and cerebral aneurysms (see Glossary). A cerebral aneurysm, usually present at birth, can develop over a number of years and may not cause a detectable problem until it breaks. As I clarified earlier, there are two categories of stroke caused by haemorrhage – subarachnoid and intracerebral.

In a subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH), an aneurysm bursts in a large artery on or near the thin, delicate membrane surrounding the brain. Blood then spills into the area around the brain causing a stroke. This tends to be managed very differently from other strokes. Bleeding may recur within weeks and there is a far greater chance that surgery will be needed to repair the artery. In the case of an intracerebral haemorrhage, bleeding occurs from vessels within the brain itself. As I stated earlier, hypertension is the primary cause of this type of haemorrhage.

After a Stroke - The effects of stroke

Trying to summarise all the possible effects of a stroke under one heading is close to an impossible task. There are simply too many individual factors, which vary from individual to individual, to take into account. In my opinion, the important issues regarding the effects of a stroke become really evident with the answers to these questions:

- Why…has a stroke occurred?

- How…could an individual be affected?

- Who…is available to support recovery?

- What…can be implemented to aid with recovery, or improve the quality of life for all those affected?

The Why? has been discussed above. The How? is discussed below. The Who? and What? are both considered in later chapters.

The specific abilities that will be lost or affected by stroke depend on:

- the extent of the brain damage

- where in the brain the stroke occurred.

In order to begin to appreciate how an individual can be affected having survived a stroke, I think that our knowledge of how the brain works should be applied. Therefore, I have decided to include an overview of the most common effects first by hemisphere, and then by individual sections of the brain.

Hemisphere strokes

Possible effects of a right-sided stroke:

- Movement and mobility: left hemiplegia (see Glossary), and some spatial and perceptual problems. •Vision: inability to see the left visual field of each eye.

- One-sided neglect: ignoring objects or individuals to the left.

- Behaviour: judgement difficulties. This is often displayed through impulsive behaviour, where the individual may ignore any disability and try to complete the same tasks as before the stroke. It can also extend to ‘inappropriate’ behaviour.

- Memory: short-term memory loss.

- Emotional health: depression.

In addition, persistent talking may be the result of right lobe damage.

- Possible effects of a left-sided stroke:

- Movement and mobility: right hemiplegia (see Glossary).

- Vision: inability to see the right visual field of each eye.

- Language: if the part known as Wernicke’s area is affected this may result in problems with understanding language; and if the part known as Broca’s area (situated close by) is affected, this may result in problems with speech.

- Behaviour: judgement difficulties, but in contrast to a right-sided stroke, the individual may require frequent instruction and feedback, thereby becoming slower and more cautious.

- Memory: increased problems with learning new tasks. In addition, paying attention, conceptualising and generalising may be difficult.

- Emotional health: depression.

Prognosis following stroke

A lack of understanding, or an inaccurate diagnosis of the underlying cause of a physical problem, can lead to inadequate and sometimes non-existent treatment options in the case of a stroke. That said, this certainly did not happen in my case, even though I presented one of the rarer cases. While recovery after stroke can be slow, difficult and sometimes only partial, I repeat that it is very clear that there is a need for immediate medical attention if a stroke is suspected. Even a small stroke (in terms of how it is displayed on a brain scan) can result in a major loss of function if it happens in one of the more ‘vital’ parts of the brain. Often patients with relatively mild symptoms actually delay calling for the doctor, or going to the hospital, and so miss the opportunity to have early treatment, which may have proved to be very effective!

Following a stroke, there is usually an area around the most severely damaged part of the brain that is only partly affected. When brain cells in the infarct die, they release chemicals that set off a chain reaction called the ‘ischaemic cascade’. This chain reaction endangers brain cells in a larger, surrounding area of brain tissue for which the blood supply is compromised but not completely cut off. Without prompt medical treatment this larger area of brain cells will also die.

Due to the rapid pace of the ischaemic cascade, the time for interventional treatment is limited to about six hours. Any longer than this and the re-establishment of blood flow and the administration of chemical treatment may not only fail to help, but may also cause further damage. Unfortunately, around 42 per cent of stroke patients wait as much as 24 hours before presenting themselves for medical treatment, which is at least 18 hours too late! In terms of a thrombotic stroke, such a delay results in a missed opportunity to effectively treat the damage caused.

When a stroke has been confirmed, the aim of initial treatment and care is to minimise the area of permanent damage and protect the penumbra, so that all subsequent treatment and care may include encouraging the healthy part of the brain to take over from the damaged cells. As I have said previously, damaged nerve tissue is not thought to regenerate, but in terms of damage to the brain (including damage as the result of stroke) there seems to be a flexible system that can allow a range of recovery in function. The medical profession does not fully understand how this happens, but it may be due in part to the interconnectedness of the nerve cells within the brain and central nervous system. It seems that a damaged brain is sometimes able to reorganise itself and may recover some function, as long as there is some continued sensory input. This development of nerve pathways is called ‘neuroplasticity’. For example, if the stroke was caused by a blocked artery, and we know from the study of the blood supply to the brain that there is some overlap between the areas of the brain supplied by the arteries, then some parts of the area affected may still survive (albeit with less blood).

There are a variety of issues, including age, gender differences, and function, which affect neuroplasticity. For example, it seems that the younger brain recovers more readily than the older brain; and women may be more successful than men in combating language problems associated with left-sided stroke. One reason for this could be that a greater proportion of women seem to have language abilities in both hemispheres.

However, the rate of potential and actual progress following a stroke is also uncertain. A few days after the stroke most people have a fast period of recovery, which then begins to slow down. However, other stroke survivors make little progress for many weeks and then suddenly display signs of improvement. In terms of the limbs, movement in the leg may start recovery before the arm. Similarly, swallowing difficulties may significantly improve within a month while speech difficulties may not begin to improve for some time, and yet then continue to improve after many other functions have stopped improving. Regarding speech, an important factor appears to be the degree to which a person made use of language before the stroke. What is important for all stroke survivors, however, is that there is evidence that recovery in function can still occur two years after the stroke.

I will obviously urge anyone to seek medical advice if their lifestyle leaves them susceptible to having a stroke. I found it hard enough to cope with having had a stroke and I did not have any clearly identifiable health risk factors. Had I been at obvious risk and done nothing, I think that I would have found coming to terms with the experience and the long road to recovery almost unbearable.

Nevertheless, I recognise that some delay in seeking medical advice is certainly understandable. Some people may dismiss their symptoms as too minor to warrant taking up a doctor’s time. On reflection, I fell into this category, despite the strange onset of a headache one night. It seems that men, in particular, subconsciously believe that if they ignore a health problem it will just go away! Other people may not go to the doctor for a very different reason. They might just be too scared of what they may find out about themselves if they visit a doctor. Unfortunately, in the case of the latter, it is possible that this itself will lead to further anxiety, which may cause them to increase their susceptibility to the factors that are the very ones of concern – for example, smoking, drinking or overeating.

Clearly, easy access to lifestyle-changing health information that reaches far beyond stroke, perhaps information like that contained in Chapter 10 ‘A Toolkit for Recovery and Prevention’, is vital. However, in terms of stroke specifically, society will benefit from a greater number of people developing a greater awareness of the risk factors, symptoms and need for action relating to stroke. The current outlook for developed societies is not very good because, as a whole, we are failing to recognise the rapid downturn in the general health of the population and are failing to address the consequences of rapidly moving towards an ageing population.

Johnson, M. (2017). Human biology: Concepts and current issues (8th Ed). Pearson.

Our natural defense against pathogens are remarkable. Nevertheless, we humans have taken matters into our own hands by developing the science of medicine. We have weaponry to help us combat pathogens. Important milestones in human health include the development of active and passive methods of immunization, which help the body resist specific pathogens; the production of monoclonal antibodies; and the discovery of antibiotics.

Active immunization: an effective weapon against pathogens

It is said that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, and this is certainly true when dealing with pathogens. The best weapon against a known pathogen is to give the body a laboratory-prepared dose of that particular pathogen’s antigen in advance so that the immune system will mount a primary immune response against it. Then, if exposed to the pathogen in the environment, the body is already primed with the appropriate antibodies and memory cells. The immune system can react swiftly with a secondary response, effectively shielding you from the danger of the disease and discomfort of its symptoms. The process of activating the body’s immune system in advance is called active immunization. This involves administering an antigen-containing preparation called a vaccine. Most vaccines are produced from dead or weakened pathogens. An example is the oral polio vaccine (the Sabin vaccine), made from weakened poliovirus. Other vaccines are made from organisms that have been genetically altered to produce a particular antigen. Of course, vaccines created from dead or weakened pathogens have their limitations. First, there are issues of safety, time, and expense. Living but weakened pathogens generally make better vaccines because they elicit a greater immune response. However, a vaccine that contains weakened pathogens has a slight potential to cause disease itself. This has happened, although rarely, with the polio vaccine. It takes a great deal of time, money, and research to verify the safety and effectiveness of a vaccine. Second, a vaccine confers immunity against only one pathogen, so a different vaccine is needed for every virus. This is why doctors may recommend getting a flu vaccine each time a new flu strain appears (nearly every year). Third, vaccines are not particularly effective after a pathogen has struck; that is, they do not cure an already existing disease. Nonetheless, vaccines are an effective supplement to our natural defense mechanisms. Active immunization generally produces long-lived immunity that can protect us for many years. The widespread practice of vaccination has greatly reduced many diseases such as polio, measles, and whooping cough. In the United States, immunization of adults has lagged behind that of children. It’s estimated that more than 50,000 Americans die each year from infections, including pneumonia, hepatitis, and influenza, that could have been prevented with timely vaccines. In many countries, vaccines are too costly and difficult to administer: Generally, they must be injected by a health care worker with some basic level of training. To get around this problem, some researchers are developing potatoes or bananas that are genetically modified to produce vaccines against diseases such as hepatitis B, measles, and the diarrhea-causing Norwalk virus. An oral vaccine against Norwalk virus has already undergone limited testing in humans.

Passive immunization can help against existing or anticipated infections to fight an existing or even anticipated infection, a person can be given antibodies prepared in advance from a human or animal donor with immunity to that illness. Usually this takes the form of a gamma globulin shot (serum containing primarily IgG antibodies). The procedure is called passive immunization. In essence, the patient is given the antibodies that his/her own immune system might produce if there were enough time. Passive immunization has the advantage of being somewhat effective against an existing infection. It can be administered to prevent illness in someone who has been unexpectedly exposed to a pathogen, and it confers at least some short-term immunity. However, protection is not as long-lasting as active immunization following vaccine administration because the administered antibodies disappear from the circulation quickly. Passive immunization also can’t confer long-term immunity against a second exposure, because the person’s own B cells aren’t activated and so memory cells for the pathogen do not develop. Passive immunization has been used effectively against certain common viral infections, including those that cause hepatitis B and measles, bacterial infections such as tetanus, and Rh incompatibility. Passive immunization of the fetus and newborn also occurs naturally across the placenta and through breast-feeding.

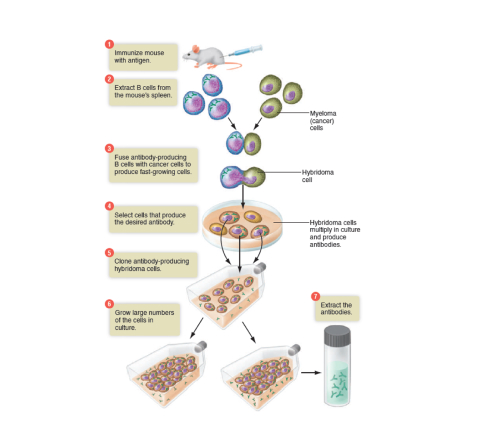

Monoclonal antibodies: Laboratory – created for commercial use

An antibody preparation used to confer passive immunity in a patient is actually a mixture of many different antibody molecules, because a single pathogen can have many different antigens on its surface. Monoclonal antibodies, on the other hand, are antibodies produced in the laboratory from cloned descendants of a single hybrid B cell. As such, monoclonal antibodies are relatively pure preparations of antibodies specific for a single antigen. Monoclonal antibodies are proving useful in research, testing, and cancer treatments because they are pure, and they can be produced cheaply in large quantities.

The image below summarizes a technique for preparing monoclonal antibodies using mice. 1 Typically, after a mouse has been immunized with a specific antigen to stimulate B cell production, 2 B cells are removed from the mouse’s spleen. 3 The B cells are fused with myeloma (cancer) cells to create hybridoma (hybrid cancer) cells that have desirable traits of both parent cells: They each produce a specific antibody, and they proliferate with cancer-like rapidity. As these hybridoma cells grow in culture, 4 those that produce the desired antibody are separated out and 5 cloned, 6 producing millions of copies. 7 The antibodies they produce are harvested and processed to create preparations of pure monoclonal antibodies. (The term monoclonal means these antibody molecules derive from a group of cells cloned from a single cell.) Monoclonal antibodies have a number of commercial applications, including home pregnancy tests, screening for prostate cancer, and diagnostic testing for hepatitis, influenza, and HIV/AIDS. Monoclonal antibody tests tend to be more specific and more rapid than conventional diagnostic tests. In the future, it may be possible to use monoclonal antibodies to deliver anticancer drugs directly to cancer cells. The first step would be to bond an anticancer drug to monoclonal antibodies prepared against the cancer. Upon injection into the patient, the antibodies would deliver the drug directly to the cancer cells, sparing nearby healthy tissue.

Antibiotics combat bacteria

Literally, antibiotic means “against life.” Antibiotics kill bacteria or inhibit their growth. The first antibiotics were derived from extracts of moulds and fungi, but today most antibiotics are synthesized by pharmaceutical companies. There are hundreds of antibiotics in use today, and they work in dozens of ways. In general, they take advantage of the following differences between bacteria and human cells:

- bacteria have a thick cell wall, human cells do not;

- bacterial DNA is not safely enclosed in a nucleus, human

- DNA is; bacterial ribosomes are smaller than human ribosomes; and

- bacterial rate of protein synthesis is very rapid as they grow and divide. Consider two examples of how antibiotics work:

Penicillin focuses on the difference in cell walls and blocks the synthesis of bacterial cell walls, and streptomycin inhibits bacterial protein synthesis by altering the shape of the smaller bacterial ribosomes.

Some antibiotics combat only certain types of bacteria. Others, called broad-spectrum antibiotics, are effective against several groups of bacteria. By definition, however, antibiotics are ineffective against viruses. Recall that viruses do not reproduce on their own; they replicate only when they are inside living cells. Using antibiotics to fight viral infections such as colds or the flu is wasted effort and contributes to the growing health problem of bacterial resistance to antibiotics.

Better Health Victoria, (2021, September 13). Fever – febrile convulsions. https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/fever-febrile-convulsions

What is a febrile convulsion?

A febrile convulsion is a fit or seizure that occurs in children when they have a high fever. This can happen in children aged 6 months to 6 years.

The fit can last a few seconds or up to 15 minutes and is followed by drowsiness. Most fits last less than 2 to 3 minutes. One in every 20 children will have one or more febrile convulsion. A febrile convulsion is not epilepsy and does not cause brain damage. Around 30% of babies and children who have had one febrile convulsion will have another. There is no way to predict who will be affected or when this will happen.

Symptoms of febrile convulsions

The symptoms of febrile convulsions include:

- loss of consciousness (black out)

- twitching or jerking of arms and legs

- breathing difficulty

- foaming at the mouth

- going pale or bluish in skin colour

- eye rolling, so only the whites of their eyes are visible

- your child may take 10 to 15 minutes to wake up properly afterwards. They may be irritable during this time and appear not to recognise you.

Reassurance for parents about febrile convulsions

The signs and symptoms of a febrile convulsion can be very frightening to parents. Important things to remember include:

Children suffer no pain or discomfort during a fit.

- A febrile convulsion is not epilepsy. No regular drugs are needed.

- A short-lived fit will not cause brain damage. Even a long fit almost never causes harm. Children who have had a febrile convulsion grow up healthy.

- If you have concerns or questions, contact your doctor. In an emergency, take your child to the nearest hospital emergency department.

- There is a medication called Midazolam that is sometimes recommended for children who have a history of febrile convulsions lasting longer than 5 minutes. Most children do not require this medication. If you would like more information about this treatment, you should talk with your doctor.

Causes of febrile convulsions

Febrile convulsions only happen when there is a rise in body temperature. The fever is usually due to a viral illness or, sometimes, a bacterial infection. The growing brain of a child is more sensitive to fever than an adult brain. Febrile convulsions tend to run in families, although the reason for this is unknown.

Treatment for a fever

Fever is a normal response to infection and is usually harmless. If your child has a fever, suggestions include:

- Keep them cool by not overdressing them or having their room too hot.

- Give them plenty to drink. It is best to give small, frequent drinks of water.

- Give liquid paracetamol or ibuprofen if your child has pain or is miserable. Check the label for how much to give and how often. Paracetamol does not protect against febrile convulsions.

First aid for febrile convulsions

If your child experiences a fit, suggestions include:

- Try to stay calm and don't panic.

- Make sure your child is safe by placing them on the floor. Remove any object that they could knock themselves against.

- Don't force anything into your child's mouth.

- Don't shake or slap your child.

- Don't restrain your child.

- Once the convulsion has stopped, roll your child onto their side, also known as the recovery position. If there is food in their mouth, turn their head to the side, and do not try to remove it.

- Note the times that the fit started and stopped to tell the doctor.

- Have your child checked by your doctor or nearest hospital emergency department as soon as possible after the fit stops.

Call an ambulance if the fit lasts longer than 5 minutes, as medications may be needed to stop the fit.