Obesity is defined as a person having a body mass index (BMI) of over 30, or the equivalent for those younger than 18 (Ministry of Health NZ). From a global perspective, the World Health Organisation (WHO) describes the prevalence of obesity as an “epidemic of massive proportions”.

In this topic we will cover:

- an overview of New Zealand statistics

- factors that contribute to obesity

- current approaches for weight loss

- some great tips for motivating your clients to stick with their weight loss journey

- referrals.

New Zealand has the third-highest adult obesity rate in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), with rates increasing steadily over the last decade (MoH, 2020). All evidence points to the fact that unless a dramatic change in our eating and exercise habits occurs the levels of obesity in NZ will continue to rise. This is likely to have a crippling effect on the NZ health care system and overall economy.

Barton and Love (2021) produced a report that outlined the economic impact of excess weight in NZ. Here are the key finding of the report:

- Direct costs: The direct cost of health care related to obesity in NZ is approximately $2 billion per year (about 8% of total health care spending).

- Indirect and intangible costs: Include the costs of lost productivity and reduced labour output as a result of obesity and obesity related conditions. These costs are estimated at between $7 billion and $9 billion a year.

Overall, over $9 billion a year can be confidently attributed to excess weight. These costs equate to 2.8% of total GDP or around $1800 per NZ resident per year.

Obesity is also clearly linked to a number of additional health conditions that can impact a person’s quality and longevity of life. The most common conditions associated with obesity are included in the following table. Barton and Love (2021) were able to calculate the attributable cost of obesity to each of these conditions:

| Condition | Prevalence/Impact in NZ | Direct Costs (attributed to obesity) |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | 5% of NZ population (245,000) in 2021 | $870 million |

| Cardiovascular Disease | Nearly one in three deaths; 1 in 23 adults affected | $2.1 billion |

| Coronary Artery Disease | Around 177,000 affected in 2019/20 | $125 million |

| Hypertension | One in three adults affected | $274 million |

| Cancers | 3.6% of new cancer cases attributable to obesity | $93 million |

| Arthritis | Increased risk with higher BMI; $500 million attributed yearly | $500 million |

Please note: These figures may be subject to change over time.

Unless a systemic change in approach by New Zealanders is adopted soon, the cost of obesity will soar and place considerable stress on the NZ health system and economy.

The last NZ Health Survey conducted on behalf of the Ministry of Health was completed in 2020/21.

The key findings of this survey in relation to obesity rates of NZ were as follows:

- Around 1 in 3 adults (aged 15 years and over) were classified as obese (34.3%), up from 31.2% in 2019/20. Around 1 in 8 children (aged 2–14 years) were classified as obese (12.7%), up from 9.5% in 2019/20. Prior to this, the rate of obesity among children had been relatively stable

- There was a significant increase from 2019/20 to 2020/21 for women (31.9% to 35.9%), but not for men

- the prevalence of obesity among adults differed by ethnicity, with 71.3% of Pacific, 50.8% of Māori, 31.9% of European/Other and 18.5% of Asian adults obese. The prevalence of obesity among children also differed by ethnicity, with 35.3% of Pacific and 17.8% of Māori obese, followed by 6.6% of Asian and 10.3% of European/Other children

- Adults living in the most socioeconomically deprived areas were 1.6 times as likely to be obese as adults living in the least deprived areas. Children living in the most socioeconomically deprived areas were 2.5 times as likely to be obese as children living in the least deprived areas

(Ministry of Health NZ – Obesity Statistics, 2020/21)

Interestingly, while obesity rates have slowly but steadily increased over recent years, a 2021/2022 update of NZ Health Survey (2020/21) data indicates that obesity rates in NZ remained unchanged between 2021 and 2022. However, due to COVID, a widespread collection of BMI was not possible during this time period, so BMI data for this update were restricted to measures taken by GPs around the country and may not accurately reflect the true state of obesity in the wider population. Regardless, obesity remains an issue for a significant proportion of adults and children in our country.

This means that the future will also see an increased likelihood that you will have clients who exhibit higher BMIs. This topic is designed to help you be better prepared for this eventuality by covering the following areas of interest.

- Factors contributing to the obesity epidemic.

- Factors influencing metabolism.

- The science of fat loss.

- Diet and weight loss – What the research says.

- Exercise and weight loss – What the research says.

- Enhancing motivation and adherence to healthy eating practices.

- Fat loss supplements.

- Referral pathways for tricky clients.

Unpacking the complexity of weight gain

Weight gain arises from an imbalance between calories expended and consumed, a well-established principle in weight loss research. Maintaining a healthy body weight hinges on achieving energy balance, where energy intake matches requirements. While this is known, many struggle to implement it effectively. To combat obesity, it's crucial to not just recognise the calorie imbalance, but to understand why it's occurring. Addressing the underlying causes of excessive calorie consumption is key to making a meaningful impact on obesity outcomes.

Recent research suggests that while energy balance is pivotal, other factors influence it. This insight paints a more nuanced picture, emphasising that while the energy in versus energy out remains central to weight gain, various factors may predispose individuals to an energy imbalance.

Upadhyay et al (2017) performed a review of the literature focusing on the casual factors associated with obesity and concluded that obesity is a complex issue with an abundance of evidence-based literature that presents obesity as a complicated medical condition caused by an inter-play of multiple genetic, environmental, metabolic and behavioural factors. These authors categorise the plethora of casual factors related to obesity as follows.

- Individual behaviours – Relating to food choices, total food intake and activity levels.

- Genetic factors – The presence of genes that predispose people to weight gain.

- Environmental factors – Sedentary jobs, family and cultural practices, income, availability of food etc.

- Metabolic factors – hormones and their effect on weight gain.

- Medications and conditions – That directly or indirectly lead to weight gain.

Please note: These fall outside of the scope of this module.

Let’s look at what the research has to say about each of these potential causes.

Individual behaviours

There is no question that in order to become overweight a person has consumed more calories than their body requires, but is this simply the result of poor nutritional choices on the part of the individual? The term “personal choice” implies human behaviour derives from conscious, volitional decisions and suggests that humans have “free will” to decide between alternative courses of action – independent of biological and environmental forces (Appelhans et al, 2011). However, people cannot be removed from their biological constraints, nor often their environment, so many argue that personal choice is undeniably linked to additional factors beyond an individual’s control.

The way that food is produced can also impact on an individual’s self-control. The human body is designed to provide self-regulation of hunger and satiety (fullness). This mechanism appears to be altered in obese populations. The palatability of our food supply has been greatly enhanced by the food industry through the inclusion of more sugar, fat, salt and flavourings. This means the “reward” stimulus for eating these types of foods (i.e. the experience of “pleasure”) has been significantly heightened which brings about a motivational drive to consume more of the same type of food.

There are also suggestions that the feelings of reward and motivation to eat these foods are grounded in the genetics and neurobiology of individuals, meaning that different people experience the reward of highly palatable foods in different ways (Appelhans et al, 2011).

The neuroprocessing of food reward has been traced to the mesolimbic system, the brains “reward” centre which also mediates the motivation to engage in sex, gambling and substance use (Berridge et al, 2010). Essentially, eating highly palatable food triggers a “reward circuit” that is primarily mediated by dopamine.

Watch the following video that explains this process.

Dopamine is not simply a “pleasure” producing hormone. Yes, it is released in response to tasty food being eaten, but it is also released in expectation of a pleasurable experience and as such can drive the motivation to consume highly palatable foods.

Rather than having a heightened experience of pleasure from eating highly palatable food, there is a hypothesis that obese populations have reduced pleasure signalling which leads to them over-consuming palatable foods in an attempt to create a heightened pleasure effect (Appelhans et al, 2011). The theory is that when the “reward” experience is dampened, individuals have stronger food cravings for sugar, salt and fatty foods as the brain attempts to seek “reward” (this has been shown by higher dopamine release in obese populations at the expectation of food intake). When this stronger drive to consume highly palatable foods is combined with easy access to such foods, individuals become highly vulnerable to becoming overweight and obese.

There is evidence that this “pull” towards highly palatable food that drives over-eating is independent of hunger or fullness signalling. In short, overweight individuals still choose to consume excessive amounts of food, it may just be that the motivation and drive to do so is stronger than in those of healthy body weight ranges.

Control of over-eating is thought to be the job of the pre-frontal cortex of the brain. The prefrontal lobe is located at the front of the brain, specifically in the frontal cortex. It is situated behind the forehead, and it is the largest of the four lobes in the human brain This area of the brain is thought to be critical for self-control, planning and goal-directed behaviours.

Multiple studies have noted that when self-control measures are required, this area of the brain is very active. Essentially, when subjects were placed in positions where self-control was necessary and a decision was required to inhibit impulses for the purpose of self-regulation, those who were able to exhibit self-control had more pre-frontal cortex activation than those who did not exhibit self-control. When the brains of obese populations were studied in this context, they exhibited the same lack of pre-frontal cortex activation as those suffering from ADHD and drug addiction (Appelhans et al, 2011).

In a study by Hare et al (2009), subjects were asked to choose between healthy and unhealthy foods. Those who consistently chose the healthier foods exhibited more pre-frontal cortex activation than those who chose the unhealthy foods. There is also evidence that activation of the pre-frontal cortex is more common in those of healthy body weights after they consume a meal, suggesting that their brains are recognising signals of satiety and exhibiting self-regulation. This post-meal pre-frontal cortex activation is associated with reduced body fat, decreased food cravings and greater success in weight loss. Obese populations did not exhibit the same level of pre-frontal cortex activation following a meal and reported continued food cravings despite having just eaten a meal that should satisfy (Gautier et al, 2012).

So, it would appear that there are a number of neurobiological differences between obese and non-obese populations that make self-control (when it comes to food intake) more difficult for some than others. The question that remains is, are some people pre-disposed to these neurobiological differences, or are they something that occurs when a person becomes obese? This is an area of constant debate. How can some people resist the temptation to consume highly palatable food while others can’t? We could also throw in another question here; why are some people driven to exercise, while others aren’t? Is this also the result of neurobiological differences?

The following short video introduces the potential role of genetics in obesity.

Please note: Take note of the reference to a hormone named Leptin.

Genetic factors associated with obesity

The genetic factors that may pre-dispose people to obesity have been a keen area of interest for obesity researchers for some time now. The notion that genetics may play a role in obesity comes from the simple fact that many of us are living in the same “obesogenic” environments with easy access to and exposure to constant marketing of unhealthy foods, yet some people become obese, and others don’t. This fact raises the question, are some people more susceptible to weight gain than others, when exposed to the same environment?

This question has prompted many studies over the last two decades, many of which have utilised twins and adopted children to see if removing an individual from a particular environment influences their chance of obesity. Since 2007, progress in molecular technologies has allowed for genome scanning and has been successful in identifying more than 100 loci associated with common forms of obesity (Albuquerque et al, 2014). These authors conducted a review of studies related to genetic influences on obesity. Here are the key findings of their report:

- Parental obesity – when both parents are overweight a child has double the risk of developing obesity in childhood. However, to date, scientists have been unable to adequately separate the genetic aspects associated with this increase in obesity from environmental factors within the household.

- Long-term studies of twins and identical twins have shown that these individuals exhibit very high correlations in fat mass and distribution of fat mass over their lifespan (despite often living different lifestyles) suggesting that BMI is highly correlated with heredity.

- Studies using adopted children have found that the BMI of adopted children corresponds more closely with their biological parents than the families they were placed with suggesting a strong genetic influence on fat mass.

- The search for the suspected genotypes that influence obesity has been challenging as studies have not been consistent enough in their findings to make definitive links. It is also very difficult to completely remove environmental factors during studies, so elements of doubt always remain as to the level of effect that is due to genetics alone.

- While a number of genome differences are noted in obese populations, these are likely to be the result of becoming obese, rather than a cause of obesity.

- There is clear evidence of gene mutation that causes extreme obesity, but these are specific medical conditions affecting a very small percentage of obese populations who would exhibit extreme obesity from a young age and do not help explain the general obesity issue.

The authors of this review concluded that although most scientists and clinicians acknowledge that while genes contribute to obesity, there is still relatively little known about the direct effect of genetics on weight gain.

One genome that has received considerable attention in recent years is the Fat Mass and Obesity-Associated Gene (FTO gene). This gene was the first obesity risk gene identified. While its mechanism is not well understood, it appears to exert influence on the hypothalamus which houses the regulation of appetite and satiety. Several variants of the FTO gene are associated with increased BMI and obesity. These variants do not appear in everyone, for example, the A-allele variant (associated with obesity) only affects 42% of Caucasians, 54% of those of African descent and 16% of Asians.

People who carry the risk variants of FTO are more likely to overeat due to a lack of satiety, eat larger portions, prefer calorie-dense foods, eat again sooner after a meal and snack more frequently (Obesity and the FTO Gene, n.d.).

To summarise, while there is a strong belief that genes can play a role in susceptibility to obesity and a number of potential genomes have been identified, at this point less than 3% of inherited susceptibility to obesity is thought to be genetic (Albuquerque et al, 2014). This means that it is still difficult to explain the rapid spread of obesity worldwide based on genetics. Genes rarely have the ability to determine an individual’s anatomy, physiology and behaviour (Albuquerque et al, 2014). However, genes may influence mechanisms of energy homeostasis, causing a variation in body weight within any given environment.

It appears that genes may simply exert some influence on how much the environment impacts an individual, rather than be a direct cause of obesity. This essentially means we are all exposed to the same environmental factors, however, genetic factors may influence our ability to process, self-regulate and when necessary, avoid the temptations of our environment.

Environmental factors associated with obesity

Many authors suggest that the global rise in obesity is driven largely by environmental factors such as high food consumption, high intake and availability of sugary beverages, lower levels of activity (both at work and in our own time) and increased screen time rather than biological factors. There is an abundance of evidence to support this theory. Here are a few key areas of concern that the research has identified:

Family dynamic

Family dynamics are thought to play a large role in the weight status of individuals as family members are likely to have similar diets, screen time, sleep practices and physical activity behaviours. They also commonly exhibit the same perceptions and attitudes to diet and physical activity, resulting in similar outcomes in terms of BMI (Albuquerque et al, 2014). Sedentary lifestyles, reduced physical activity, reduced sleep and increased screen time have all been independently associated with increased weight gain (Yadav and Jawahar (2023). A study by Heinonen et al (2013) examined the effects of sedentary behaviours on obesity and found that for every additional hour of screen time viewed, subjects increased their waistlines by 1.8cm for women and 2cm for men.

Cooking skills and knowledge of nutritional principles are also reflective of the family environment. If a family has limited time, knowledge or willingness to cook their own meals, there becomes a reliance on processed food options. This may also offer one logical solution to the obesity crisis. A study by Arslan et al (2023) found that obese people showed more cognitive restraint, less emotional eating behaviours and improved their BMI as their food preparation and cooking skills improved.

Sleep has also been consistently found to impact on obesity levels. Attitudes to sleep are heavily influenced by the family dynamic. Less than 6 hours or greater than 8 hours of sleep a night is associated with weight gain. Sleep has also been extensively studied in children with findings that even 1 hour of reduced sleep over time correlates with higher levels of obesity (Yadav and Jawahar, 2023). Children from lower socioeconomic households report less sleep than those from higher-income households (most likely due to later bedtimes).

Socioeconomic status and food availability

Obesity prevalence is higher amongst lower socioeconomic groups in developed countries and is also highly correlated with the level of education of parents. Lower socioeconomic groups exhibit both lower levels of physical activity and higher obesity rates. Studies have shown a socioeconomic gradient in relation to childhood obesity with parental education levels one of the strongest predictors of childhood obesity, followed by parental occupation and income. (Albuquerque et al, 2014).

Parental education levels appear to influence the family’s knowledge and beliefs around nutrition, with higher education levels facilitate better understanding and utilisation of available nutrition information (Alder et al, 1994). Children from more educated parents are more likely to eat breakfast and fruit and vegetables; consume fewer snacks and are less likely to eat foods with high-energy content, such as sweetened beverages (Albuquerque et al, 2014).

Children living in more deprived areas tend to eat less fruit and vegetables, but more low-cost energy-dense foods like sugar and sweets, fats, processed meats, salty snacks and soft drinks compared with higher-income households. Lower-income household members also participate in less physical activity (Albuquerque et al, 2014). A meta-analysis by Wu et al (2015) showed that low socioeconomic position is associated with a 41% higher risk of childhood obesity in North America, Europe and Oceania. This is thought to be because families living in poverty have different priorities than those who are better off, with less importance placed on healthy eating and physical activity levels. Surveying has revealed that lower socioeconomic households value energy-dense food (over healthy food) and perceive many healthy food options as beyond their resources or too expensive to buy (Albuquerque et al, 2014).

Over the last decade there has been a growing prevalence of fast-food options in lower socioeconomic areas. Yadav and Jawahar (2023) report that there are up to 30% less supermarkets in low-income neighbourhoods, but statistically more fast-food options in these areas than higher income areas. This, combined with a higher tendency in lower socioeconomic populations to perceive fast food options as more affordable than healthy options means that the average BMI of those in lower socioeconomic areas has increased steadily.

A reliance on processed food

Food intakes that include large amounts of highly processed foods are associated with higher obesity levels. Consumption of highly processed foods has increased markedly over recent years. In the USA and UK, it is reported to make up nearly 60% of these nation’s diets. In Australia, it is more like 42% (Castles, n.d.). While we have limited recent data for NZ, a 2021 University of Otago study looked at the consumption of highly processed foods in NZ children at ages 12, 24 and 60 months and found that highly processed foods made up 45%, 42% and 51% of energy in diets of children at these ages (Castles, n.d.). This shows that our children are not off to a very good start with nutrition. But how does consuming highly processed food lead to obesity?

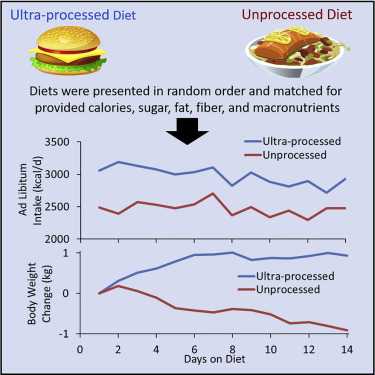

A study by Hall et al (2019) compared diets high in processed food to those low in processed food and found that even when keeping macronutrient content the same, meals that were ultra-processed resulted in greater food intake and weight gain over a two-week follow-up compared to consumption of non-processed foods. In the study, subjects of healthy body weights were split into two groups. One group were only allowed to consume foods of a processed nature and the other group largely ate unprocessed foods. The food options were calorie and macronutrient-matched, but subjects were instructed to consume as much or as little as they liked of the foods based on hunger and satiety. The processed food group consumed more daily calories over 2 weeks and as such gained an average of almost a kilogram of body weight. Conversely, those in the non-processed group, ate less calories daily and actually lost an average of almost a kilogram of body weight over the 2 weeks.

This strongly indicates that by simply eating a diet higher in processed foods, a person will likely eat more total calories and put themselves at a higher risk of weight gain.

Advertising

The marketing techniques employed by the food industries across multiple mediums are also thought to have contributed to the increase in fast food and highly processed foods. Adults appear to be less affected by marketing strategies, but experimental studies with children and adolescents have shown a greater increase in certain fast foods following advertising exposure. Food advertising is often aimed at children with the express intent of making them lifelong consumers (Boyland et al 2016).

A study by Watkins et al (2022) looked at how often NZ children were exposed to unhealthy food advertising every day. The study collected data by small cameras attached to 90 children that recorded what they saw. The cameras collected data every day for 4 consecutive days. The overall findings of the study were that children were exposed to an average of 554 brands in a 10-hour day. Food and beverage products made up 20% of these brands which equated to 68 junk food ads per day. 43% of the brand exposures happened at school, 30% at home and 12% in stores.

Work environment

In recent decades, the nature of work has changed due to globalisation and technological advances making sedentary work and non-standard patterns of work (i.e. shift work) increasingly common. Eng et al (2022) studied the effects of long working hours and sedentary work on NZ employees. The data was collected from over 1.5 million working NZ men and women between 30 and 64 years of age. The authors of this report suggested sedentary occupations (i.e. those that spent over 50% of the working day seated) were more common for females (41%) than males (33%). Approximately, 20% of both men and women also worked in a job that required some form of night shift. Both shift work and long periods spent seated (as in sedentary jobs) have been strongly associated with increased BMI. A clear association exists between work-related energy expenditure and weight gain. There is also a small correlation between long work hours (above 40 hours) and weight gain, with a higher risk associated with 55 hours a week or above (Virtanen et al, 2020).

Food delivery

Access to highly palatable food has never been easier in Western society. Nowadays, people need only reach for their smartphone and food can arrive at their door. Since COVID hit in 2019, NZ has seen a massive increase in the use of food delivery apps. Uber Eats alone has added more the $162 million to the NZ economy each year (Wynn, 2022). Kiwis appear to be willing to pay up to 25% more than if they had gone out to get the food themselves and around 25% of young people report being regular users of these food delivery apps. School drop-offs in Auckland at lunchtime became so frequent that school principals were forced to ban students from ordering food to school (Wynn, 2022).

The use of food delivery apps in the USA is an even bigger business showing growth of 23% in the last 4 years and returning $26.8 billion to the USA economy. While a wide range of foods including healthy options are freely available for consumers, the most frequently used platforms report that the most commonly ordered foods through the apps are cheeseburgers and fries, pizza, nachos, cheesecake, pork ribs and other calorie-dense options (Stephens et al, 2020),

Research into the negative health impacts that the use of these apps is having on people is limited at this point in time, however, the latest World Health Organisation European Obesity report has flagged food delivery apps as a likely contributor to the rising obesity problem as they encourage even more sedentary behaviours and play a significant role in increasing consumption of high fat and high sugar foods and drinks (Roxby, 2022).

Metabolic factors contributing to obesity

It’s not my fault, I have a slow metabolism

First, let’s clear up a common misconception regarding metabolism and becoming overweight. Overweight populations do not have a slow metabolism. In fact, the basal metabolic rate of overweight or obese people is usually higher (to accommodate for the extra fat tissue they must maintain, and the increased difficulty associated with performing normal bodily functions (Marcus, 2013). While there is a genetic variance in metabolic rate between individuals, the reality is, that weight gain is the result of consuming calorie amounts that are over and above the requirements of the body. Like the genetic influences discussed earlier, individual variances in metabolic rate may influence the likelihood of gaining weight, however, only if excessive calories are consumed on a chronic basis.

Hormones linked to obesity

Let’s turn our focus on the metabolic effects that obesity causes in the body (i.e., those that occur once a person becomes obese). The metabolic effects of obesity are often referred to collectively as “metabolic syndrome”. Metabolic syndrome refers mainly to alterations in the way that hormones are produced and recognised by the body. One of the main effects of metabolic syndrome is insulin resistance, which can culminate in impaired glucose tolerance, high cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes and premature heart disease (Singla et al, 2010). Insulin resistance is a term used to describe impaired glucose sensitivity. This occurs when the cells in your muscles, fat and liver don’t respond to insulin as they should. This means that insulin’s role in regulating blood sugar by facilitating the entry of glucose into cells is impaired, leading to high circulating blood glucose levels and a high risk of developing diabetes.

Obesity is characterised by an excess of adipose tissue or body fat. Adipose tissue is a major endocrine organ in the body that produces various hormones that regulate metabolism. An increase in fat cells leads to imbalances in the production of these hormones, which can have various metabolic effects (Singla et al, 2010). Of these hormones produced by adipose tissue, those that play an important role in body weight regulation are listed in the following table:

| Hormone | Function | Obesity Association |

|---|---|---|

| Leptin | Thought to play a major role in regulating appetite and desire to move. | Levels of leptin are elevated in obese populations. |

| Visfatin | Thought to act like insulin as a means of keeping blood glucose levels stable (may increase fat storage). | Levels of visfatin are increased in obese populations. |

| Apelin | A substance that is elevated in obese populations and appears to alter glucose and lipid use for energy. May be an insulin inhibitor that plays a role in insulin resistance. | Levels of apelin are elevated in obese populations. |

| Resistin | Provides resistance to insulin. It is a hormone released due to inflammation (in this case of fat cells). | Levels of resistin are increased in obese populations. |

| Adiponectin | This hormone aids insulin in glucose uptake and increases the use of fat as a fuel. | Levels of adiponectin are decreased in obese |

While the exact roles and effects of many of these hormones are still being investigated, the role of leptin in obesity has been extensively researched. Let’s move on to learning about the role of leptin in obesity and discuss the effects of obesity on the production and effectiveness of insulin.

Leptin

Leptin is a protein-derived hormone secreted from fat cells. Leptin is thought to have several roles including growth control, metabolic control, immune regulation, insulin sensitivity regulation, and reproduction, however, its most important influence is in body weight regulation.

Leptin is the chief regulator of the “brain-gut axis”, which provides a satiety (fullness) signal to the hypothalamus. When leptin is recognised by the hypothalamic leptin receptors, they suppress food intake and promote energy expenditure. Put simply, leptin is produced by the stored fat cells. The more fat cells you store, the more leptin your fat cells produce. This leptin travels in your bloodstream to the brain, where leptin receptors respond by reducing appetite and increasing the desire to engage in movement. In a well-functioning system, this should lead to the maintenance of a stable body weight. The image below helps explain how leptin works.

When food intake increases (or energy expenditure decreases) and a positive energy balance is present, we tend to store increased amounts of body fat. This fat tissue produces the hormone leptin. Leptin receptors in the hypothalamus recognise leptin and the brain establishes that we have enough fat stores, so reduces appetite and stimulates a desire to move more.

![[ADD IMAGE'S ALT TEXT]](/sites/default/files/Leptin.png)

Conversely, a body with very little body fat will produce very little leptin. The brain will recognise this lack of leptin and as a means of survival will increase appetite and decrease calorie expenditure in order to ensure the body has sufficient stores of fat for survival. Click through the following images to show how this mechanism is supposed to work.

The first column shows a body with low body fat stores (empty adipose cells). This reduced leptin signalling leads to an increase in appetite leading us to eat.

The second column shows a body with full adipose cells, leading to increased leptin secretion and signalling. This results in a reduction in appetite leading to reduced calorie consumption.

It appears that this regulatory signalling system becomes faulty in obese populations. This has become known a “leptin resistance”. Leptin resistance is thought to be caused by either a defect in intra-cellular signalling associated with the leptin receptors or decreases in leptin transport from the blood to the brain (Gruzdeva et al, 2019).

It was initially thought that this faulty effect could be the result of a gene mutation, but this has been found to be extremely rare in humans and typically results in the development of morbid obesity directly after birth. Instead, the primary cause of leptin resistance is thought to be that excessive levels of leptin in the blood (due to large stores of body fat) reduce the amount of leptin that can cross the blood-brain barrier.

There is an additional theory that inflammation also plays a role in blocking the transport of leptin across the blood-brain barrier. As adipose cells enlarge, an inflammatory protein called C-Reactive Protein (CRP) is released. It is thought that CRP binds to leptin and prevents it from crossing the blood-brain barrier (Singla et al, 2010).

Essentially, this means that as more body fat is stored and an increase in leptin production occurs, less leptin appears to reach the brain where leptin receptors are located. This leads to the brain thinking that little leptin is in the blood and the subsequent increase in appetite and decrease in motivation to expend calories leads to a rapid increase in body fat stores. A brain receiving no leptin signals, believes that the body has little to no fuel reserves (body fat), so resorts to protective measures including a sharp increase in appetite and a slowing of the metabolism (to conserve energy). It is thought that this double effect leads to rapid weight gain.

The following is a great video that explains the effects of leptin resistance, the mechanism of insulin resistance, and how the food industry and environment we live in have led to the global obesity crisis.

To summarise, becoming obese triggers a number of alterations to hormone release and effectiveness which leads to disruption of the body’s normal weight management mechanisms. Many of these changes are driven by inflammation associated with the rapid increase in the size of adipose cells. These changes in hormone secretion lead to increased appetite, decreased motivation to move (and burn calories), and altered substrate use resulting in a propensity to store body fat rather than use it for energy. These things combined result in a cycle of fat storage that results in continuing weight gain. Add to this a food industry that promotes easily accessible, highly palatable foods and obesity becomes rife.

The great obesity debate

While the basic cause of obesity is undoubtedly an imbalance of calorie expenditure to calorie consumption, as we have already discussed, the factors that contribute to wide-spread obesity in a population are multidimensional. Jenkin et al (2011) believe the true explanations for the obesity epidemic in NZ are often convoluted by the input of various stakeholders which has led to a debate over the key casual factors. These debates are often played out in the media which cause confusion in the general public as a multitude of core reasons for obesity are discussed. They may also be the reason why progress in halting the increase in obesity is slow.

The competing interests of the food industry and their marketing teams, the public health sector, the exercise industry and political groups result in the blame for obesity being constantly shifted from one cause to another.

Jenkin et al (2011) performed an inquiry into the way the causes of obesity in NZ are framed by two of the main stakeholder groups involved in this debate: “Industry” - which included Food Manufacturers and Marketing Agencies; and the “Public Health Sector” - which included non-government organisations, professional associations and independent advisors. The inquiry collected the opinions of 17 major food companies and marketing agencies along with 14 public health organisatons. Here are the key findings of the report:

- Both groups described the key contributing factors to obesity as “complex”

- Industry referred to obesity as an “issue” or “concern” and labelled it a “health-threat/problem”. Public Health referred to obesity as an “epidemic” and recognised the wide-reaching costs associated with obesity across our economy.

- Both groups accepted that genetics were not responsible for increases in obesity.

- The industry group maintains that the main cause of obesity is freely chosen individual lifestyles characterised by over-consumption of food and lack of physical activity. They denied that advertising and the cost and availability of high-calorie, nutrient-poor food was the main issue and argued instead that poor attitudes to food, lack of motivation to change, lack of knowledge, poor willpower and denial of weight issues were the key factors.

- The Public Health disagreed strongly that increases in obesity were down to individual characteristics instead blaming an “obesogenic environment” where nutrient-poor energy-dense food was cheap, readily accessible and “shamelessly promoted”. They identified the key contributors as sugary drinks, highly processed foods and foods high in fat, sugar or both. Of course, the industry contests these suggestions and has drawn on evidence to refute these claims.

As you can see, the different agendas of these key players leads to an ultimately pointless debate that takes energy and focus away from a solution to the issue of obesity in NZ. This constant debate slows the potential for solutions and strategies to combat the issue. The industry group maintains that the “self-regulation” approach to food advertising is working and has described in detail its voluntary efforts that have already been employed to address obesity (for example, product ingredient changes, food labelling and sponsorship of education, community sport and physical activity events). The public health group disagrees labelling the approach as one where “the wolves are guarding the henhouse" and instead would like to see more regulations, restrictions or bans (across all advertising mediums) on the marketing of unhealthy foods.

The food industry argues that the main issue is a lack of physical activity rather than overeating, the exercise industry believes a combination of excess food and lack of activity causes, while public health groups believe obesity is due to ubiquitous marketing and availability of low-cost, energy-dense/nutrient food. Those with political affiliations argue that social inequity is the root cause.

In truth, all of these factors contribute to the obesity crisis we find ourselves faced with in this country, but a lack of cohesion between stakeholders and the constant debate leads many New Zealanders to place the blame for their increasing waistlines on factors outside of their control.

To summarise, the factors contributing to widespread weight gain are absolutely multi-faceted, but the over-riding fact remains. The reason people are becoming overweight is because they consume too many calories. This is most likely due to the result of personal choice and living in an obesogenic environment. The extent to which individuals are affected is also influenced by genetic factors and hormonal alterations. Regardless, we have an obesity issue in this country, and it appears that it will get worse before it gets better. Personal trainers will continue to play a key role in disseminating quality advice to overweight clients and in enabling clients to achieve their weight loss goals through a structured programme of exercise and healthy eating practices.

When you lose fat, where does it go?

While the answer is somewhat complex and involves high-level math and science, this question is answered beautifully (and simply) in this great video.

Note: While this video is 20 minutes long, it is definitely worth it!

Try it out

Let’s turn our focus to what research suggests regarding the best way to assist our weight-loss clients in achieving a healthy body weight (and maintaining it).

Let’s discuss some commonly used and researched approaches for weight loss.

If the root cause of obesity is consuming an excess of calories over time, then the solution for obesity (and a return to a healthy body weight) is pretty obvious. Create a calorie deficit.

There are two primary ways in which you can create a calorie deficit:

- Consume less calories

- Expend more calories

Research has found a few proven methods in relation to helping people create a calorie deficit and achieve meaningful and sustainable weight loss. There are a number of weight loss strategies that can be employed to lose weight that have been backed up by research. The most common of these include:

- Nutrition advice.

- Calorie restriction diets.

- Exercise approaches alone.

- Calorie restriction diets and exercise.

- Very low-calorie approaches.

- Meal replacement approaches.

- Prescribed obesity medications (outside the scope of this module).

- Obesity surgeries (outside the scope of this module).

There is plenty of evidence to suggest that a number of these approaches can lead to meaningful weight loss. Franz et al (2007) performed the largest systemic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials that had a minimum 1-year follow-up (to date). The review included 80 clinical intervention studies and articles including over 26,000 participants.

- 51 of studies included a “diet alone” weight loss strategy

- 17 included diet and exercise strategies

- 7 studies used meal replacement interventions

- 11 studies used very low-calorie diets

- 20 studies included a weight loss medication intervention (Orlisatat and Sibutramine)

- 28 studies included a “nutrition advice only” intervention

- 2 studies included exercise-only interventions.

Here are the key findings of the review:

- All weight loss interventions that included a reduced calorie diet and/or weight loss medication resulted in weight loss during the first 6 months.

- After 6 months, weight loss plateaus were evident but none of the groups experienced a complete regression to baseline weights at the one-year mark.

- Those in the “nutritional advice only” or “exercise only” interventions experienced minimal weight loss across all time points.

- Those who were in diet-only groups experienced a mean weight loss of 4.9% at 6 months, 4.4% at 12 months, 4.4% at 24 months and 3% at 48 months.

- When exercise interventions were added to diet interventions mean weight loss was increased to 7.9kg at 6 months, with 4kg of weight loss maintained at 48-months.

- Stricter calorie restriction through the use of meal replacement shakes resulted in 8.6kg weight loss at 6 months and 6.7kg loss maintained at 12 months. Very low-calorie diet subjects lost 17,9kg at 6 months followed by rapid regain (10.9kg at 12-months, 5.5kg at 36 months).

- Exercise alone groups experienced only 2.4kg of weight loss at 6 months reducing to 1kg at 12 months.

The results are shown in visual form below:

In summary, all of the subjects lost weight in these clinical trials, showing that initial weight loss is possible using a variety of approaches. What is also clear from the data is that neither nutrition advice nor exercise approaches alone are effective means of achieving weight loss. The addition of exercise to reduced calorie diets results in better initial weight loss outcomes but it appears obesity medications can achieve much the same results. Very restrictive diets lead to the most significant initial weight loss.

It should also be noted that Interventions and follow-up in these studies were provided by registered dietitians in 51 studies, by behavioural specialists in 17 studies, and in three studies by nurses or physicians. Support was also available to the subjects when needed in the form of behavioural therapists, exercise physiologists, and physicians throughout the trials. This level of support is often absent for individuals attempting weight loss on their own.

What is also apparent from the data is that there is a general trend towards regaining lost weight, the longer the trials continued. Also of note is that 31% of the participants of these studies dropped out with the most common reason given being that the intervention was too hard to adhere to. This means that the majority of data used in this review was from those who completed the trials. If the data of the 31% of the subjects who failed to complete the trials was added, the authors suggest that the longer-term follow-up weight loss data would likely show even less of a weight loss outcome at 12, 24 and 48 months.

Therefore, while a range of weight loss approaches work in the short term, it appears that a return towards baseline weight appears to occur in most instances.

Diet only approaches

The term “diet” (in reference to weight loss) is a practice by which calories are often severely restricted to achieve a substantial daily calorie deficit. Diets (by design) are goal-orientated, and as such they end at some point. This means that while all calorie restriction diets work in the short term, research suggests almost none work long-term, as when people end reduced calorie approaches the weight piles back on.

Here is what the research has to say about calorie-restrictive dieting as a long-term approach to weight loss:

- In 2002, 231 million Europeans attempted a diet through an organised weight loss management group. Almost all reported initial weight loss but only 1% kept the weight off after an additional 12 months (Kravitz, 2009).

- Dieting leads to unfavourable eating habits in the long term. A history of dieting is often associated with rigid control of diet, followed by disinhibited eating patterns (Gallant et al, 2012). This means people swing between severe calorie restriction and uncontrolled binging. These authors concluded that dieting damaged the chances of maintaining a healthy weight. Alonso et al (2015) also suggest that dieting leads to neurological mechanisms that cause dieters to become overly responsive to food, increasing temptations. This results in food having increased reward value making it harder to resist.

- A meta-analysis of 29 long-term weight loss studies reported that more than half of the lost weight was regained within two years, and by five years more than 80% of the lost weight was regained (Loveman et al, 2011). The National Eating Disorders Association of America (2005) suggests that weight regain is even higher with 95% of all dieters regaining their lost weight and more within 1-5 years.

- Tomiyama et al (2013) reviewed 22 research articles examining the long-term effects of dieting completed between 1993 and 2013. To be included in the review, studies needed to have a minimum follow-up period of 2 years. The average amount of weight loss maintained by participants from baseline to 2-year follow-up was only 0.94kg. Dieters showed non-significant improvements in blood pressure, blood glucose and blood lipid levels compared to control groups but none of these correlated with weight changes.

This is just a selection of findings from a vast number of studies and reviews that have looked at dieting as a form of weight loss. The same themes come through time and time again. Rigid dieting results in meaningful initial weight loss, but very few people are able to maintain this approach for long periods of time, resulting in the regain of at least some, if not all of the weight lost within the next few years. There are a number of suggestions for why this happens:

- A body will not simply put up with ongoing calorie restriction forever. It will more likely adapt. When you begin restricting the number of calories a body usually receives, the body adapts to run on fewer calories by slowing down metabolism and attempting to store the calories it receives. This appears to be a built-in biological mechanism that exists to allow us to survive in times of food scarcity (Mattson et al, 2019). This causes people to regain most of the weight they lost.

- Benton and Young (2017) suggest that hormonal mechanisms that stimulate appetite remain raised even a year after dieting has been maintained. Given that most diet approaches end well before this time period, the same drivers that led to over-consumption in the first place will still be present at the end of the diet period.

- Jean and Malkova (2016) reviewed the available research around appetite signals in obesity and concluded that diet-induced weight loss results in long-term changes in appetite gut hormones that appear to favour increased appetite and weight regain.

- The National Weight Control Registry at the University of Colorado has tracked over 10,000 people over at least 5 years on their weight loss journey. Those who supplied data to the registry reported that weight maintenance became easier after 2 years of adherence to a calorie-deficit diet and that the chances of long-term weight loss management increased after 2-5 years on a calorie-deficit diet. This time period appears to be well outside of the time an average dieter is prepared to subsist on a calorie deficit for.

Add to these findings the fact that those obese individuals who start dieting are still bound by potential genetic, hormonal and environmental and social factors that have contributed to their weight gain and it is easy to see why weight loss is a very difficult undertaking to be successful in long term.

This was evidenced by the systemic review and meta-analysis by Franz et al (2007) discussed earlier where 31% of the subjects withdrew from the various studies by the end of the 1-year follow-up citing that the approaches were too difficult to adhere to. Franz et al (2007) also report that community-run weight management programs tend to experience higher dropout rates than clinical trials (like the one’s involved in their review).

It appears that even commercial weight loss approaches fail to produce meaningful weight loss outcomes. McEvedy et al (2017) reviewed 25 trials and reviews of meal replacement, calorie-counting and pre-packaged meal programmes run by commercial organisations (e.g. Jenny Craig) and concluded that these programmes frequently fail to produce clinically meaningful weight loss and have high dropout rates suggesting many consumers find the dietary changes unsustainable.

However, there is no getting away from the fact that in order to lose weight, individuals must achieve a chronic calorie deficit. There are a number of ways to achieve this (e.g. diet, exercise, or both). According to Johnston et al (2014) who conducted a meta-analysis on a number of diet approaches for weight loss, calorie restriction is the primary driver of weight loss, followed by macro-nutrient composition. However, as previously discussed, diet interventions that create a substantial energy deficit are likely to be countered by physiological or biological adaptations that resist weight loss. The first and most obvious question in relation to this is, how much of a calorie deficit do we need to create?

Most low-calorie diets suggest consumption of 1000-1500 calories per day, with many studies and weight loss societies recommending a 500-750 calorie deficit in their guidelines for weight loss (Kim, 2021). Very low-calorie diets of less than 800 calories per day have also been used in trials but are not recommended for routine weight management despite showing evidence of effectiveness. The reality is, there is no recommended calorie deficit for enhancing the chances of long-term weight loss maintenance as there are many and varied factors associated with long-term outcomes. The ideal calorie deficit for an individual is one that they can adhere to for the foreseeable future and that satisfies their basic health requirements. That said, the majority of the literature points towards a deficit of at least 500 calories per day with suggestions that this level of deficit should be possible without experiencing extreme hunger or fatigue issues (Van De Walle, 2019).

Macronutrient manipulation

Research to date is pretty clear, any sustained calorie deficit will result in weight loss regardless of the macronutrient composition of the food you eat. Wait what? That would mean a person could lose weight on a diet of beer and pies (as long as a calorie deficit is maintained). Well....yes.

Christchurch-based Newshub reporter Julian Lee did just that when he set out to explore claims that it didn’t matter what you ate when trying to lose weight as long as you consistently achieve a calorie deficit. Lee had his calorie requirements estimated by a qualified nutritionist at 2,500 calories a day. On his beer and pie diet, he consumed 1600 calories in the form of 3-4 pies a day (depending on the calorie content of each pie). Once a week, he swapped one pie for 3 beers. After 4 weeks, Lee found that he had lost 8kg on the diet. Of course, there were negative effects of eating just pies including cognitive impairment. At the end of the experiment, he described himself as “delusional right now” and said he was “losing the plot!”.

The results of this non-scientific experiment have also been backed up by scientific literature. When calories are controlled, the macronutrient composition of food eaten does not impact the amount of weight lost with similar weight loss observed in those who consumed a variety of macronutrient compositions. Boaz (2015) conducted a meta-analysis comparing low-fat, high protein and low-carbohydrate diets in calorie-controlled trials and concluded that manipulation of macronutrient composition does not appear to be associated with significantly different weight loss outcomes. In other words, provided a calorie deficit is maintained, weight loss outcomes will be similar regardless of the macronutrient composition of the food eaten.

While the pie and beer approach is definitely not recommended, it does highlight the simplicity of the task for a weight loss client. To lose weight and keep it off, you must create a sustainable calorie deficit that can fit into your daily lifestyle and provide the nutrients you need for good health. There are a multitude of ways to do this, but the key is to find an approach you can adhere to. This is where macronutrient manipulation may be effective, and this has led to a number of popularised diets promoting low carbohydrate and high protein intakes. The theory behind low carbohydrate diets hinges on the fact that some carbohydrates elevate insulin secretion, thereby directing fat towards storage in adipose (fat) tissue.

While the type of macronutrient eaten may not impact weight loss outcomes in calorie-monitored situations, this may not be the case in situations where individuals are not calorie-restricted. There is clear scientific evidence that certain macronutrient intakes are easier to adhere to than others. This is critical to long-term weight loss outcomes, as while a number of approaches can lead to significant initial weight loss, keeping the weight off appears much more difficult.

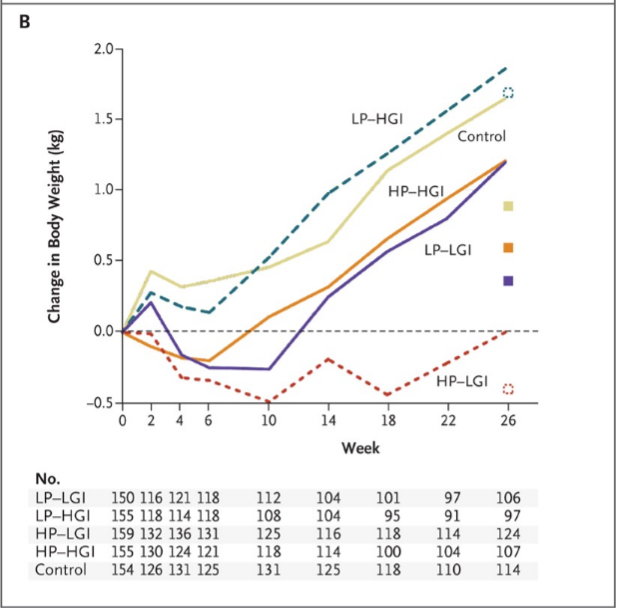

Research has provided strong indications of the best way to manipulate macronutrients to enhance adherence to a calorie deficit diet long term. Larsen et al (2010) studied the effects of different dietary approaches on subjects who had already lost weight following calorie-restricted diets. Of the 938 subjects involved in the trial, all had lost at least 8% of their total body mass following a low-calorie diet. Larsen et al (2010) randomly placed each subject into one of five diet groups to assess how each diet approach prevented weight regain over the next 26-weeks. The key difference between this study and other studies was that the subjects were instructed to eat ad libitum (as much as they felt like) but were only able to eat foods from a list corresponding to the macronutrient diet group they had been placed in. The five diet groups were:

- A low-protein (13%) and low-GI carbohydrate diet.

- A low-protein (13%) and high-GI carbohydrate diet.

- A high protein (25%) and low-GI carbohydrate diet.

- A high protein (25%) and high-GI carbohydrate diet.

- A control diet – that followed the general dietary guidelines of the subject’s home country.

The results of the experiment are shown in the following image:

548 (71%) of the subjects completed the 26-week intervention they were assigned to. More subjects dropped out of the High GI carbohydrates groups and low protein groups than the high protein groups. The results show that the rate of completion and successful maintenance of weight loss were better in participants who were assigned to the high protein diets and to the low GI diets than the low protein/high GI diets. In addition, those in the high protein and low GI carbohydrate group continued to lose weight after the intervention began. The higher protein diets were achieved by reducing total carbohydrate load and the inclusion of only low GI carbohydrates in this group further reduced the glycemic load (total carbs x GI number). These results support a number of findings from previous research that indicate that reducing glycemic load is important for controlling body weight in obese patients. The high protein, low GI group was the only group that hadn’t gained weight by the end of the trial.

As an additional experiment, Larsen et al (2010) had some of the subjects receive their food free for the 26 weeks, while others received dietary advice only (and had to pay for their food). Those following high protein diets that were given their food for free gained 2.7kg less body weight than the low protein groups that were given food, whereas the difference was only 0.54kg between the groups that had to buy their food.

The authors concluded that a moderately high protein intake along with lower GI carbohydrate sources both improved adherence to the diet and maintenance of weight loss, therefore appearing to be the optimal macronutrient balance for the prevention of weight gain. This obviously has relevance to populations wishing to prevent the onset of weight gain in any context also. Another study by Larsen et al (2010) compared a high protein (HP) diet with a high carbohydrate (HC) diet. The two diets were calorie-matched, with similar amounts of sugar and fat in each, and calculated to provide a moderate calorie deficit. Details relating to the diets compared are shown in the following table:

| Nutrient | HP diet | HC Diet |

|---|---|---|

| Energy (kJ) | 5615 | 5602 |

| Protein (g) | 107 (32% of E) | 67 (20% of E) |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 138 (41% of E) | 191 (58% of E) |

| Sugars (g) | 73 | 83 |

| GI/GL | 46/61 | 52/93 |

| Dietary fibre (g) | 23 | 24 |

| Total fat (g) | 38 (25% of E) | 32 (21% of E) |

| Saturated fat (g) | 11 | 10 |

| Cholesterol (mg) | 298 | 87 |

The results of the study show that the participants lost weight on both diets, but that the HP diet was more successful for both short and longer-term weight loss. As the graph shows those on the HP diet (in green) not only lost more weight initially but had greater weight loss when the diet was maintained for a year.

The effectiveness of higher protein diets

A review of scientific evidence of diets for weight loss completed by Freire (2020) agrees that diets that contain at least 20% of total energy as protein appear to offer advantages in terms of weight loss and body composition in the short term. Higher protein diets assist weight loss in a number of ways but most probably because:

- Protein is the most satiating macronutrient (remains in the stomach for longer than other macros). This makes it easier to avoid over-eating. A critical review by Halton and Hu (2004) reported that there was convincing evidence that a higher protein intake increased thermogenesis (calorie burn producing heat) and satiety compared to lower protein intakes and that high protein meals led to reduced subsequent food intake. This is supported by Kohanmoo et al (2020) who performed a meta-analysis and systemic review on the effect of short- and long-term protein consumption on appetite and appetite-regulating hormones. These authors review 68 studies and articles on the subject and concluded that acute ingestion of protein not only suppresses appetite by staying in the stomach longer, but also decreases production of the hunger hormone ghrelin.

This effect can be quite powerful. Weigle et al (2004) found when they increased the protein content of subjects’ diets from 15% of total calories to 30%, the subjects consumed an average of 441 less calories each day of the trial without intentionally restricting anything.

- Protein uses more calories to digest than the other macros giving it a higher thermic effect (TEF). About 25% of protein calories ingested are used to break down protein for absorption (when eaten in food form). This compares with carbohydrates (6%) and fat (around 2%).

- A high protein intake increases the chances of maintaining good levels of Iron intake (also benefits levels of other micro-nutrients such as B12, Folic acid, calcium).

Important

While the term “high protein” diet is used a lot in weight loss circles, in reality, a high protein diet does not require eating lots of meat, drinking protein shakes, and generally seeking protein sources out every time you eat. The research that has been completed in this area typically uses “high protein” diets that contain around 25% of total energy as protein. In Western populations (and especially in those that consume animal products) achieving this much protein in the diet requires no additional focus on protein. The WHO suggests most people who eat a balanced diet achieve daily protein requirements with ease.

Active populations require more protein than sedentary individuals. However, there is no compelling evidence that consuming over 2g of protein per kilogram of body weight offers additional benefits to athletes. A 70kg athlete involved in a mix of resistance and cardio training would require between 1.3-1.5g/kg of protein a day. This translates to 91-105g of protein a day. Here is an example from the Australian Institute of Sport (2009) that shows just how easily protein these protein levels can be attained.

| Quantity of food required to provide needs for a 70 kg athlete | Amount of protein (g) | ||

| Breakfast | 2 cups cereal 300 ml milk 2 slices toast 2 tablespoons jam 1 cup juice |

6 12 8 0 2 |

|

| Lunch | 2 bread rolls each with 50 g chicken + salad 1 banana 1 fruit bun 250 ml flavoured low-fat milk |

41 2 6 13 |

|

| Dinner | Stir-fry with 2 cups pasta + 100 g meat + 1 cup vegetables 1 cup jelly + 1 cup custard |

50 13 |

|

| Snacks | 750 ml sports drink 1 carton yoghurt 1 piece fruit 1 cereal bar |

0 10 1 2 |

|

| Analysis | 166 g (2.3 g/kg) |

Table source: Australian Institute of Sport "Position on Protein" (2009)

As you can see, the athlete has not focused on consuming large portions of meat or relied on protein shakes to easily attain their protein needs. Protein is found in a variety of foods, so before dramatically increasing the protein intake of a client, consider the amount of protein they are actually consuming. A simple diet log analysis will help you confirm this.

High-fat diets

There has been a lot of recent interest in the ketogenic diet and weight loss. While the ketogenic diet appears to have some advantage over high carbohydrate diets in terms of reducing appetite and hunger and has shown significant weight reductions, many studies of the diet have been largely uncontrolled. Additionally, a number of negative effects such as constipation, halitosis, headaches, muscle cramps and muscle weakness were commonly observed. Studies into more worrying effects on lipid profiles, liver function and cardiovascular risk factors also remain inconclusive (Freire, 2020).

So, for now, higher protein diets appear to carry less risk, although this author warns that while high protein, low carbohydrate diets on balance are useful to elicit initial weight loss effects, they should be used in the short term rather than a diet for life. This is due to some concern that remains over the effects this diet approach can have on metabolism and gut health, and because animal-derived protein and fat have been associated with higher mortality (death) than plant-based protein and fat (Freire, 2020). This author suggests that on current evidence, a more balanced macronutrient split (while maintaining a calorie deficit) could achieve similar weight loss results without the associated health risks. In particular, she references the fact that data shows an increased mortality rate with long-term intake of both low and high carbohydrate intake, but that an intake of around 50-50% carries minimal risk.

Weight loss on a plant-based diet

Adoption of plant-based diets is growing because evidence has shown some health benefits when compared with omnivorous diets. Plant-based diets have been shown to protect against chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes and some cancers, however, further research is required to clarify whether these benefits are related to a reduction in animal products or an increase in fruits, vegetables and fibre (Freire, 2020).

A plant-based diet appears to aid the maintenance of a healthy body weight with individuals on plant-based diets usually presenting with lower BMI than non-vegetarians. But are plant-based diets also associated with meaningful and sustainable weight loss?

Two meta-analyses on this subject would suggest they are. Combined evidence from reviews by Banard et al (2014) and Huang et al (2016) reported a clear association between adopting a plant-based diet and weight loss that was attributed to lower energy intakes on these diets. However, it should be noted that not all studies in the meta-analysis reported meaningful weight loss outcomes and many failed to achieve the same level of weight loss as the higher protein approaches discussed above. The authors of these reports also mentioned the importance of those adopting plant-based diets to seek appropriate nutritional guidance to avoid potential nutrient deficiencies.

Intermittent fasting

Intermittent fasting has recently received a lot of attention as a nutritional strategy for weight loss. The appeal of being able to “eat normally” during short periods of the day, resonates with many who struggle to give up the foods they enjoy. Several variations of intermittent fasting have become popular. The most commonly followed are the 16:8 (no food between 6pm and 10am) and alternate-day approaches. Weight loss experiments using an intermittent fasting intervention have resulted in average weight loss of between 4-10% over dieting periods of 4-24 weeks, although not all studies have reported meaningful weight loss (particularly those including alternate day fasting). Freire (2020) suggests there is growing evidence to demonstrate the metabolic health benefits of intermittent fasting (especially in animal studies), but that fasting approaches do not appear to offer superior weight loss outcomes than other continuous calorie restriction diets.

A systemic review of the literature regarding intermittent fasting and weight loss was completed by Welton et al (2020) who agreed that while intermittent fasting shows promise as a weight loss tool, more research is required to understand the long-term effects of this approach.

Following her systematic review on dietary approaches to weight loss literature, Freire (2020) concluded that people will continue to follow popular trends in weight loss, despite most evidence coming from personal accounts, blogs and weight loss articles, rather than from rigorously controlled research. At this point in time, clinical research evidence remains inconclusive making it impossible to recommend an optimal dietary approach for weight loss. In the short term, different diets promote different degrees of success with all that create a meaningful and ongoing calorie deficit resulting in weight loss. However, the long-term results of these dietary approaches elicit small differences which do not instil enough confidence to recommend one approach over another.

Freire (2020) believes there are a number of important questions still to be answered by research. Why do some individuals experience successful weight loss, whereas others are more resistant to weight loss (using the same approach)? How do different diets change things like hormonal secretion, gut microbiome composition, and gene expression, and how do they effect energy, function and appetite (in the long term)?

Knowing which weight loss approach works best

While the information on the various weight loss approaches doesn’t give a clear indication of what approach is best for weight loss, it does suggest that a variety of dietary approaches do result in meaningful weight loss. This is actually a good thing! It means that approaches can be tailored to individual preferences as long as three key concepts are understood.

- The dietary approach must create a calorie deficit to result in weight loss.

- The dietary approach must be something that a client can adhere to long-term.

- The dietary approach should contain high-quality foods to ensure basic health requirements are met (i.e. micronutrients).

In order to satisfy the first point, a client must seek the advice of a nutrition specialist to determine what their daily requirement for calories is. Once this is established a meaningful calorie deficit (typically around 500 calories a day) can be calculated.

Next, the client must be educated enough to make decisions about food choice. This will of course include understanding the calorie density of foods but should also include information to ensure they meet their daily needs for micro-nutrient intake.

Finally, the dietary approach must be something that the client can maintain for the foreseeable future. Adherence to a weight loss/maintenance diet is without question the most difficult part of this process.

It's important to consider adherence when exploring other weight loss options, so that you keep it in mind when evaluating each approach.

The reality is any calorie deficit dietary approach will result in weight loss if the client adheres to it. A study by Dasinger et al (2005) compared a range of dietary strategies for weight loss and concluded that the amount of weight lost was associated more with adherence to a diet, than the type of diet approach used. These findings have been supported by a number of other studies over recent years prompting Freire (2020) to conclude that the diet approach used is not nearly as important as the ability of an individual to adhere to it. There are many factors that influence adherence to a dietary programme including but not limited to food preferences, cultural or regional traditions, food availability, food intolerance and motivation. Having a wide range of dietary options to choose from is a positive, as clients can tailor an approach that gives them the best chance of adherence.

Weight loss solutions need to focus on approaches that can be maintained for the rest of a client’s life. This means they can’t be hugely restrictive as a person will never be able to adhere to them long-term. While a rigid “diet” may be a useful approach to lose an initial amount of weight, there needs to be a longer-term solution in place to ensure the hard work is not undone when the diet ends. Weight loss solutions also need to address the various environmental and social factors that may impact on a client’s ability to adhere to a reduced-calorie diet. All current evidence suggests that a diet approach alone is very unlikely to result in long-term weight loss and management.

Exercise and weight loss

The huge meta-analysis on weight loss approaches by Franz et al (2007) suggested that exercise alone did not compare well with dietary and medication weight loss approaches, but this doesn’t mean exercise is not a meaningful contributor to successful weight loss outcomes. Before we look at the added effect that exercise has when combined with a calorie deficit diet, let’s take a look at the impact of different forms of exercise alone on weight loss.

Cardio and weight loss

Cardio was long thought to be the best exercise to perform to lose weight. This was presumed on the basis that cardio burns more calories during a session than other forms of training. In recent years, however, cardio approaches have been sidelined in favour of resistance and HIIT training approaches with suggestions that doing cardio may even “make you fat”.

This has led to confusion about whether cardio is an effective tool for weight loss. Let’s clear up one thing immediately though. Cardio does not make you fat!

On a whole-body level, aerobic training increases cardiovascular function, aerobic capacity, basal metabolic rate and fat metabolism. Such changes in whole-body metabolism induced by regular aerobic exercise are undoubtedly beneficial to promote weight management.

Dr Jose Antonio (co-founder of the International Society of Sports Nutrition) has written dozens of peer-reviewed articles on the mechanism of weight loss and the role of exercise and states there is more than ample evidence to support the use of cardio exercise for healthy weight management and weight loss including:

- Longitudinal training studies on obese children showing aerobic training results in a loss of body fat.

- Longitudinal training studies on obese adults showing aerobic training results in a loss of body fat.

- Studies reporting that those who do the most cardio over a 15- to 20-year period exhibit the lowest levels of body fat.

- Studies that show athletes that are engaged in highly aerobic exercise have single digit body fat percentages.

- Studies that show cardio athletes with a higher training volume have a lower % fat than those with a lower training volume.

The problem is many of these studies were on athletes (who had never been obese) and those that were performed on obese populations did not account for the diets of the subjects involved.

Thorogood et al (2011) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials assessing the effect of isolated aerobic exercise on weight loss in overweight adults. The review included 14 trials involving 1847 subjects. The duration of the aerobic exercise programmes varied from 12 weeks to 12-months duration. The authors concluded that moderate-intensity cardiovascular exercise induced modest reductions in weight and waist circumference in overweight populations. While consistent aerobic training resulted in multiple cardiovascular and additional health benefits, it was largely ineffective as a weight-loss approach on its own.

Swift et al (2014) agree that large, randomised trials that have evaluated weight loss following aerobic training programmes in line with ASCM physical activity guidelines of 150-250 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity a week have observed either no change in weight or modest effects on weight loss (less than 5kg). These authors concluded that overweight and obese adults who adhere to an exercise program consistent with public health recommendations without a dietary plan involving caloric restriction can expect to experience weight loss in a range of no weight loss to approximately 2 kgs. The authors also noted that despite the absence of dramatic weight loss, the numerous additional benefits of cardiovascular training (that can help reverse the negative health impacts of obesity) should not be ignored.

Resistance training and weight loss

Cardio on its own has a very modest effect on weight loss, what about lifting weights?

Unfortunately, it appears that resistance training on its own has a similar (moderate) effect on weight loss to cardio when performed in isolation. Wewege et al (2021) performed a systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect of resistance training in healthy adults. Their review of 58 studies found that resistance training elicits average reductions of 1.4% body fat percentage and 0.55kg of fat mass compared to non-exercise control groups.