Periodisation is defined as the planned manipulation of training variables (exercise mode, volume, intensity, etc) in order to maximise training adaptations, the peak for important competitions, and prevent over-training (Lorenz & Morrison, 2015). Periodisation is most relevant for higher-level athletes who are trying to plan their training schedule around important competitions to be at peak performance level for important competitions or the end of the competitive season.

In this topic we will focus on:

- the process of creating a periodised annual programme plan for resistance training.

- This will include a complete overview of the periodisation planning process and some guidance for how the resistance training modes to come will fit into an annual training plan.

- you will learn the specific information you need to be able to create engaging session plans for athletes that fit into this periodised plan.

In reality, an athlete’s periodised plan for sports performance would include both cardiovascular and resistance training methods concurrently. To simplify your ability to absorb this information, we will only cover the resistance training approach to periodisation in this topic.

While periodisation techniques offer flexibility in programming for diverse athletes, our primary emphasis in this discussion lies in utilising the periodisation process to tailor programmes for sporting clients (athletes). This focus proves especially beneficial for individuals aspiring to assume strength and conditioning responsibilities within team sports settings. It's important to note that the knowledge gained from this topic extends beyond just this context and is applicable to individual athletes participating in various competitive events, such as athletics and powerlifting. Ultimately, the objective of this topic is to provide you with the proficiency to craft well-structured, periodised resistance training plans specifically catering to the needs of your sporting clients.

A periodised programme is a training plan that brings about peak performance through a structured and progressive increase in training stimuli while managing fatigue and allowing for super-compensation or improvement in recovery (Turner, 2011).

Periodisation is a method of organising the training year into phases, where each phase has specific aims for the development of the athlete. A periodised programme divides an athlete’s annual training plan into a number of smaller, more manageable phases of training. Each phase targets a specific training goal or series of attributes to be developed within a designated period of time. Periods of appropriate overload and recovery are appropriated within each phase. The most common training phases included in a periodised plan are:

- The Preparation (preparatory) Phase – essentially the pre-season phase of training

- Competition (competition) Phase – the duration of the competitive season

- Transition (off-season) Phase – The time between the end of the competitive season and the start of pre-season (essentially the off-season).

The goal of a periodised plan is to manage and coordinate all aspects of training to bring an athlete to peak performance at the most important part of the competitive season or to manage a high level of performance across a long season. The process of breaking a year-long training plan into more manageable segments simplifies the focus of each phase of training for both athlete and trainer. It also recognises the fact that an athlete cannot remain in a state of peak condition all the time!

Periodisation is a concept where the design of a programme alters the physiological stress experienced by an athlete in regular intervals, periods, and phases of a training plan.

A carefully crafted periodised programme optimises training adaptations while guarding against the development of the over-training syndrome.

- Too little

- Optimum

- Too much

- Distress

Periodisation is regarded as a superior model for developing an athlete’s peak performance, however, it is believed that an athlete can only maintain peak performance for 2-3 weeks, so the ability to coordinate this with a future competition event is a fundamental skill for all strength and conditioning coaches to master and one that can only be achieved by having a firm grasp of the science and practice of periodisation (Turner, 2011).

Key aspects of periodisation

Essentially, any variable in a training programme can be periodised. Most commonly, periodisation manipulates the following variables:

- Training mode used and exercise choice

- Volume & intensity of exercise via manipulation of:

- Duration of exercise

- Sets

- Load

- Repetitions

- Rest periods

- Frequency of training a body part or system

- Movement speed and effort

While periodisation can appear to be quite a complex process, it is rooted in some quite simple scientific theory. The Principles of Training that you are already very familiar with, specificity, individualisation, progressive overload, and so on, all still apply.

A periodised programme in its simplest form can be depicted by the concept named "General Adaptation Syndrome." It's built upon the idea of super-compensation and acknowledges that some forms of training require more time for recovery compared to other training methods. Additionally, it acknowledges that certain types of training hold greater significance than others in the lead-up to competition, with different forms gaining prominence as the competition date approaches. (ASCA Coaching Accreditation Manual, 2022).

Through a periodised programme we apply training stress to an athlete’s system in a systematic and targeted manner, with progressive increases in training load at times away from competition and the use more specific reduced volume exercise approaches during competition. This manipulation of variables ensures progressive overload occurs to allow the athlete to perform at their best when it matters.

If the plan is poorly designed, then unfortunately it can have the opposite effect on performance. Planning too much volume, with insufficient recovery can lead to performance deficits and fatigue related burnout as this graph from the Australian Strength and Conditioning Association Coaching Accreditation Manual (2022) shows.

Performance can decrease if training is too hard or recovery and super-compensation have not been planned.

Creating annual periodised plans

Periodised plans vary in length depending on the training goal. Most commonly a periodised training plan reflects a calendar year, although, for some athletes, they might work on a plan of up to 4 years in duration, for example those targeting the Olympics.

Key Considerations for Periodised Plan Preparation

Consider these factors when preparing a periodised plan for an athlete:

- Sport type: Is it:

- seasonal (e.g., football, basketball)

- tournament-focused (e.g., golf, tennis)

- peaking-focused (e.g., track and field, swimming)?

- If seasonal, determine the start and end of the season.

- If a tournament or peaking sport, identify the dates of significant competitions.

Let’s focus on the development of an annual periodised training plan (1 year).

Identify peak timing

Begin by determining the exact point on the calendar when the athlete needs to be at their best. This could align with a specific phase of the season (like playoffs, finals, or an end-of-year tour) or a particular competition (such as the Regionals/National championship or the World Cup).

Work backward

Once you have these key dates, work backward from the peak performance point to the starting point of the sport's training. This helps you understand how much time you have for each training phase.

Adapt to the sport and athlete

Depending on the sport and the athlete, the focus of performance might be on a single peak or multiple peaks spread throughout the year. This is particularly common for individual event athletes.

Examples of peaking cycles

Here are some examples to illustrate various peaking cycles and their application. Depending on the sport/athlete the performance calendar could have a singular peak focus, or multiple peaks required at different points across the year (this is more common with individual event athletes).

Navigate through the following examples to illustrate various peaking cycles and their application using the allows beneath the image.

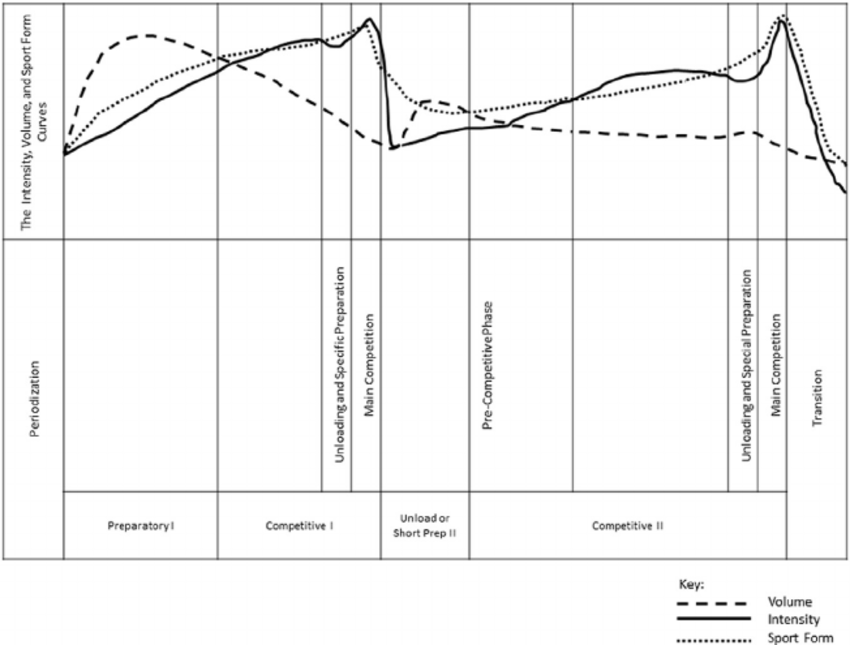

Single peak towards the end of a season

This is the general concept of a "periodized" year of training where "X" is the main competition at the end of the season.

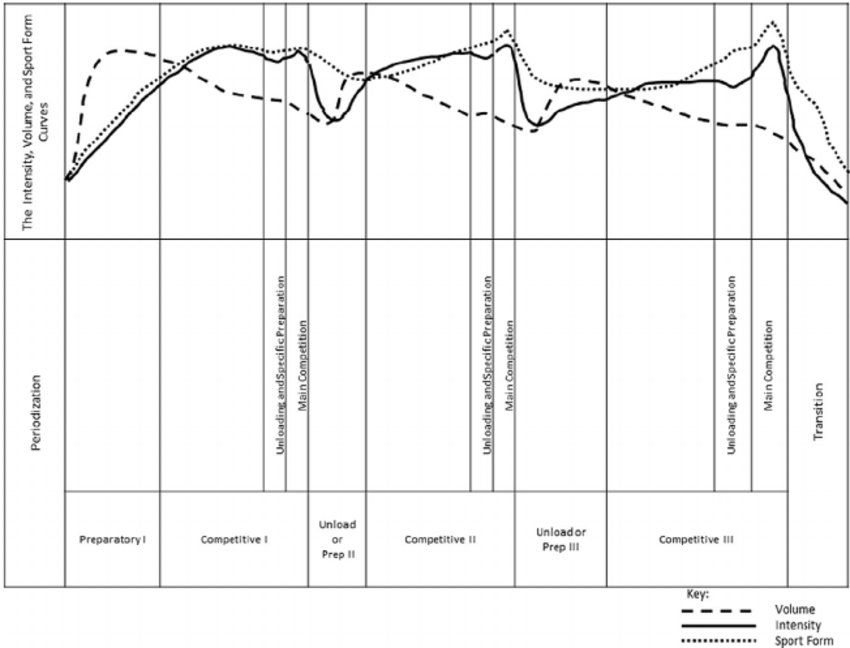

Bi-cycle (two) peak approach

Tri-cycle peak approach

As you can see in the images above, the intensity and volume of training are manipulated throughout the training year so that a peak performance state is reached during the competition events of primary importance. As a rule of thumb, the volume of training is highest in the preparatory phases of training and reduces as you enter competitive phases. The intensity builds steadily using the principle of progressive overload across preparatory phases and is kept high in competitive phases to ensure training gains are maintained (principle of maintenance).

Once you have the key dates in place and have identified when the training will begin, it is time to divide the training year up into training periods. The focus of each training block will be dependent on the physical qualities that are important for performance in the sport (e.g., strength, endurance, power, etc). Once you have identified these training focuses and know what time frames you have to devote to training them, it is much easier to make monthly, weekly, and individual session plans.

The structure of a periodised programme will vary significantly for different athletes as the demands of sports are wide and varied. The periodisation approach is also highly dependent on the training age of the athlete and the level that they compete at.

Let’s take a closer look at how to break up the training year into segments and the key terminology you need to be aware of that is associated with this process.

Divisions of a periodised plan

A periodised training plan breaks up the training into easy-to-manage training blocks, each with a specific purpose. Some key terms have been developed to categorise these training blocks. Online research of these terms will reveal some inconsistencies in their use depending on the origin of the information (some countries appear to use these terms slightly differently) and disagreement over what each term constitutes.

While these inconsistencies exist, the meaning behind each of the terms are pretty clear. It can be confusing not to have universal terms for the periodisation programming process, however, if you are consistent with your terminology and explain the process to your clients in an easy-to-understand terms, you will be able to use these phases to break down the training year into absorbable blocks for your programming.

Let’s focus on the most common terms associated with the divisions of a periodised plan. These are:

- Macrocycle

- Training phases

- Mesocycles

- Microcycles

- Training units

Macrocycle

The macrocycle is generally the total period of time available to prepare, train for and compete in the primary competition (or competitions) the athlete has targeted. For the purpose of this topic, the macrocycle will constitute the annual plan (or one year), although this can differ depending on the nature of the sport and level of competition. Some publications use the term macrocycle to denote phases of the training year (e.g. in-season, off-season etc), others will simply refer to a macrocycle as the time you have before the key competition event you are training for. In most cases with strength and conditioning, a macrocycle will refer to the time you have to work with athletes before they are required to achieve peak performance state. If you are working with the same team or athlete year in and out, then you will likely adopt an annual plan (year-long) macrocycle.

Training phases

These are large divisions of the macrocycle. While there is also some inconsistency in the use of this term, the most common training phases in a periodised annual plan are:

- Preparation (preparatory) Phase

- Competition (competition) Phase

- Transition (off-season) Phase

Note: in some publications, the term “transition” is used to denote a phase that exists between the preparation and competition phases. In the context of this topic, the term transition will represent the period between the end of the competition phase and the start of the preparation phase.

Depending on the sport and the length of time allocated to each of these training phases, trainers will often break these phases up even further into:

- The General Preparation Phase

- The Specific Preparation Phase

- The Pre-competition Phase (usually only used in pre-season competition phases– i.e., where a team might play pre-season fixtures that do not count as part of the main competition)

- The Competition Phase

- The Transition/Off-season Phase

Mesocycles

The term “mesocycle” is most often described in the literature as being 4–6-week blocks of training as this appears to provide the optimal time frame for adaptation (Turner, 2011). This also recognises that each 4–6-week block of training will likely have a slight (or substantial) change in training purpose. The length of each of the training phases listed above will differ depending on the time available. Once you know the length of the training phase, you can allocate mesocycle training blocks, for example, an 8-week general preparation phase would likely be split into 2 mesocycles (general preparation 1 & 2) both 4 weeks in duration, whereas a 6- week specific preparation phase could be one longer mesocycle of 6 weeks, or 2 shorter 3-week mesocycles.

Microcycles

Microcycles are a further breakdown of mesocycles (into shorter training blocks). In most literature, microcycles are referred to as independent “weeks” of trainings. This is the context in which we will use them for this topic. Once your microcycles are established, you can begin to plan your individual sessions. The main changes that occur within the microcycles are small and structured manipulations to the training variables, i.e. sets, reps, load, and rest.

Sessions

This refers to individual session plans which will have a specific focus. There may be multiple sessions within a day, for example, a strength session in the gym, may be followed later in the day by a skills session on the field.

Training units

This is a term used to reflect the parts of a training session. Allocating training units to a session can be done to ensure volume and intensity are measurable across sessions, microcycles and mesocycles so that progressive overload is achieved in preparation phases and maintenance and tapering phases can be systematically applied. Guidance on how to calculate training units is covered later in this topic.

Periodisation Considerations

The length of each periodised training phase is typically influenced by two factors:

- the duration of the competitive season

- the desired length of the athlete's off-season.

In recent times, professional sports seasons have been expanding, leading to a reduction in the length of the off-season. This trend has resulted in shorter off-season periods for athletes.

Coaches are now having to carefully manage player loads in-season to avoid fatigue-related decrements in performance. See the following example:

Training Phase

The following is generic example of a periodised plan timeline for a standard winter sport in the Southern Hemisphere. This would be reflective of club-level sport which begins in the middle of March and runs through to August/September. It is the fundamental planning periods and phases for a winter team sport.

General Preparation Phase

(12-11 till 22-12)

6 weeks

Specific Preparation Phase

(7-1 till 3-3)

7 weeks

Pre-Competition Phase

(4-3 till 17-3)

Competition Phase

(18-3 onwards)

End of Competition period till the start of next Preparation Period.

Also if a break between Xmas- New Year (23-12 until 6-1)

Source: ASCA level 1 coaching accreditation manual

The following information outlines the typical training emphasis for each of the primary training phases. Although the specific focus of every training phase might need to be manipulated, the majority of team sport athletes tend to adopt the ensuing approaches within each training phase:

The preparation (preparatory) phase

The preparatory phase is where the athlete is working on the general (first) and then specific (second) conditioning aspects of their training that will ready them for competition. This phase typically exhibits the highest training volumes and a gradual rise in training intensity as the competition phase approaches.

The preparation phase can be broken into smaller training phases which narrow the training focus even further. Common blocks in the preparatory phase include:

| Phase | Description |

|---|---|

| Initial General Phase | Athletes engage in general fitness and conditioning routines during this stage. The goal is to improve an athlete’s work capacity and maximise adaptations in preparation for future workloads (Turner, 2011). Training may include general strength, hypertrophy, or muscular endurance exercises. Athletes could work at workloads 30-40% higher than during the competition phase (ASCA, 2022). |

| Specific Preparation Phase | Training becomes more customised to address the specific conditioning requirements of the sport they participate in. This phase serves as a transition into the competitive phase. Training is more specific, targeting physical capacity, movements, and intensity specific to the sport's physiological profile. Power and plyometric exercises may be introduced to enhance attributes like speed and agility. Workloads 10-20+% higher than the competition phase could be achieved (ASCA, 2022). |

| Pre-Competition Phase | Certain trainers might integrate a pre-competition phase, implementing even more specialised methods to prepare athletes thoroughly for upcoming competitions. Training load might be slightly higher than the competition phase, even during competitive fixtures. |

| The Competitive (Competition) Phase | The primary goal is to sustain physical fitness attributes in elite athletes well-adapted to training. Lower-level athletes may continue improving their condition during this phase. Training volume gradually decreases while intensity remains high. Workloads of 40-70% of the preparation phase might be sufficient to maintain condition. The focus shifts to adequate recovery time between competitive events. Resistance training emphasises maintenance. |

| Transition Phase | Athletes have a window of time between the end of competition and the start of the new preparatory phase. This phase includes rest and recovery but may also incorporate lower-intensity sessions to minimise the de-training effect. |

General periodisation approaches with resistance training

In general, resistance training for sporting athletes will follow a fairly similar progression year to year (of course this will be somewhat dependent on the specific goals of individual athletes). The typical progression of resistance training in a periodised programme looks something like this:

| Training Phase | Description |

|---|---|

| End of Transition Phase / Start of General Preparation Phase | Anatomical Adaptation (getting the body ready to train) - This will likely involve some lighter lifting sessions (muscular endurance focus) and technique work to ready the body for more intense resistance training. |

| General Preparation Phase | Often where maximal strength training is performed. Hypertrophy may also be worked on in this phase if desired by the athlete and coaching staff. Depending on the phase's length, power training methods may also be introduced. |

| Specific Preparation Phase | This is where general training gains are converted into sport-specific improvement. Power and plyometric training are often included, with exercises becoming more specific to the key sporting movements required in competition. |

| Competitive Phase | The focus revolves around preserving the progress made in the preparatory stages and managing the interplay between competition, relaxation, and rejuvenation. Sessions tend to be brief yet intense. A blend of contrasting training methods encompassing strength, muscular endurance, and power is used to uphold training advancements efficiently. The frequency and duration of strength training are reduced during this phase. |

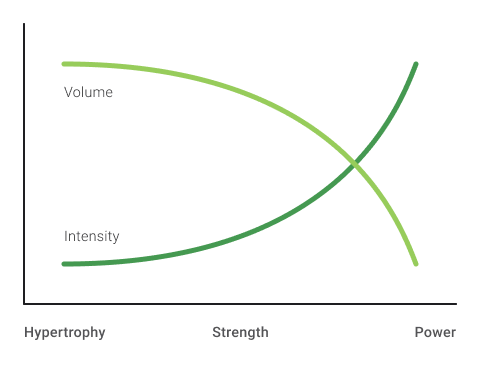

Volume and intensity of resistance training

The following table presents prevalent overarching guidelines for volume and intensity during resistance training across the primary mesocycles. Observe that training volume tends to be greatest in the preparation phases, and it diminishes in the competition phase. Intensity reaches its peak in the lead-up to the season and is upheld at a heightened level during competition. Notably, rest and recovery hold the utmost significance during the competitive phase, aligning with the prime goal of achieving peak performance during competitions.

| Training Phase | Intensity | Volume | Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Preparation Phase | LOW | HIGH | LOW |

| Specific Preparation Phase | MEDIUM/HIGH | MEDIUM/HIGH | LOW |

| Pre-Competition Phase | MEDIUM | MEDIUM | MEDIUM |

| Competitive Phase | HIGH | LOW | HIGH |

Another factor that a strength and conditioning coach must take into account is how the training programmes they develop align with the broader performance plan throughout the training calendar. The following image illustrates that as the competitive season progresses, the significance of strength and conditioning training often becomes less prominent compared to technical, developmental, and skill training.

The following illustrates the increasing emphasis placed on sports skills and tactics as the competitive season unfolds, in contrast to the levels of training volume and intensity.

| Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| European terminology | Preparation phase | Competition phase | Season transition (active rest) |

| Traditional American terminology | Pre-season | In-season | Off-season |

| American strength/power terminology | Hypertrophy Strength/power | Peaking | Active rest |

Try it out

The two most common methods are:

- Linear Periodisation: This traditional approach involves gradually adjusting training intensity and volume over time in a linear progression. Typically, it starts with a phase of higher volume and lower intensity during the initial preparation period and then transitions to lower volume and higher intensity as the competitive phase approaches.

- Non-Linear (Undulating) Periodisation: In this approach, there are frequent changes in training intensity and volume within shorter timeframes, often within a week. This strategy allows for more variety and can be particularly beneficial for clients aiming to address multiple aspects of their fitness concurrently.

Let’s look at each in more detail.

Linear periodisation

Also known as the “traditional” or “basic” approach, linear periodisation is the most common approach to periodisation for people starting out with resistance training or beginning the general preparation phase of their training. With linear periodisation you see the typical increase in training intensity with a concurrent drop in training volume as competition approaches.

Linear periodisation dedicates periods of training to achieving specific training goals. For example, you might dedicate 4 weeks of a preparation training phase to increase muscle mass, then focus for the next 4 weeks on strength development and finally complete a 4-week block of power training. These prolonged mesocycles with narrow focus allow sufficient time to improve or achieve a training goal. This approach is considered appropriate for athletes with a training age of “zero” (novices) or for those beginning a general preparation phase after a period of reduced training (off-season).

Benefits and application of Linear Periodisation

- Linear periodisation is great for building a strong foundation of condition and progressing towards the improvement of one training mode at a time (e.g. a strength athlete training for a competition).

- It is a great programming approach for those who are newer to training. Most new clients need to build a strong foundation before they can attempt more advanced training methods. Linear periodisation is a great way to steadily improve towards training goals.

- It is also useful for athletes who have few competition events as it allows a slow and steady build-up to peak for competition.

- For sporting athletes’, it is most common to use linear periodisation during the earlier preparation phases of training.

It is important to note that even linear periodisation should contain ebbs and flows in training volume. This usually sees an increase in volume over a few weeks followed by a brief de-load training period where volume is reduced before increasing again. 4-week mesocycle training blocks are usually arranged in a 3:1 loading paradigm whereby the load gradually increases over three microcycles before a de-loading microcycle is introduced in week 4. This de-loading phase reduces fatigue and allows adaptations to occur (super-compensation).

ASCA (2022) suggests a common approach used is to structure a training mesocycle with the following microcycles (usually a week-long each):

- “Normal” or “Basic” weeks – a normal training week with load set at determined capabilities. Note: if one after the other you would still want to apply progressive overload.

- “Load” or “Shock” weeks – with an increase in volume of 20-35% over normal weeks.

- “De-load” weeks – A reduced volume training week to allow for super-compensation (volume is reduced by 25-35+% compared to normal week).

The duration of a given mesocycle will ultimately determine how many of each week are included in a programme. ASCA (2022) suggests that some trainers prefer short mesocycles of 3 weeks, including one week of each of the above training weeks. Others prefer a 6-week mesocycle in which there are a variety of ways to structure the week e.g. 2 x 3-week cycles, or 2 weeks of each training week, 3 basic, 2 shock, 1 de-load and so on.

According to ASCA (2022), a typical approach to this form of programming may look like this for someone beginning their general preparation resistance training. The image below shows 3 x 4-week mesocycle approach (12 weeks of training).

The training begins with 3 “normal” weeks with a progressive overload in volume each week for the first 3 weeks, then a “shock” week is introduced, followed by a “de-load” week to allow for super-compensation to occur.

The next two mesocycles follow the same approach using 2 x normal weeks, 1 x load week and 1 x de-load week. In this example, the volume builds by between 10-25+% each month. You can see that the load volume in week 4 becomes a normal week in week 10 (when the athlete is in much better condition).

This linear progression in volume can continue through the preparation phase with subsequent mesocycles moving through different training modes, for example, muscular endurance, hypertrophy, strength, and power, depending on the requirement of the sport. As the competition phase begins and training volume needs to decrease, you will often apply the reverse of this approach as a means of tapering volume, while keeping intensity high.

As an athlete's experience with strength and conditioning training progresses and their adaptations start to level off, a higher degree of diversity in training becomes necessary to further enhance their physical condition. Due to their improved work capacity, these athletes demand greater training volumes, leading to an increased necessity for planned recovery sessions as well (Turner, 2011).

Consequently, the periodised program transforms into an undulating, wave-like loading approach, often administered at the microcycle level. This is referred to as Non-linear. This is known as Non-linear Periodisation.

Non-linear (undulating) periodisation

This approach involves constantly changing exercise variables during every microcycle (usually every week, but potentially day by day). This is accomplished by adjusting load, volume and intensity constantly (while still remaining within recommended volume guidelines for the phase of training).

Due to the variability needs of these more advanced athletes, non-linear periodisation also includes accommodation of multiple components of fitness within the same microcycle (e.g. strength, power, and speed work). Some are included for the purpose of maintenance and others for the purpose of improvement (Turner, 2011). This is managed by cycling high-intensity – low volume sessions of training with higher volume-lower intensity sessions (e.g. heavy and light training days). This is where resistance training approaches like cluster training and contrast training come into play.

This approach can be implemented microcycle by microcycle (week) or occur within the same week. Non-linear periodisation relies on constant change in training stimuli throughout training phases to promote adaptation or maintenance of training gains (Turner, 2011).

Benefits and application of Non-linear Periodisation

- Allows for the inclusion of multiple components of fitness within the same microcycle

- Offers training variability which is vital for Intermediate to Advanced athletes (2+ years of training) if they are to continue to make training gains

- Allows for the maintenance of some components of fitness, while others are improved

- Useful in the competition phase of training as a means of maintaining multiple components of fitness through the in-season period (as training volume is reduced). Athletes who have longer seasons will benefit by changing up variables more frequently.

- Helps with motivation for athletes towards training as the training year progresses as there is more variety in the training week.

- Helps avoid neural overload (fatigue) in advanced athletes who often have a very high volume of training, e.g. CNS fatigue from too much power training.

- Non-linear periodisation makes it easier to manipulate training sessions in competition if, for example, a competition or game is cancelled or postponed. Trainers can manipulate where they place higher and lower intensity sessions depending on the schedule of competition.

Types of non-linear periodisation

According to Nuckols (2018) there are two main types of non-linear periodisation:

- Weekly undulating periodisation

- Daily undulating periodisation

Weekly undulating periodisation

Changes to volume and intensity of exercise take place weekly and generally match higher intensities with lower volumes and vice versa. For example, a linear approach to strength training might have you lifting 70% of your 1RM on week 1, 75% on week 2, 80% on week 3 and 85% on week 4. A weekly undulating approach might look like 70% of 1RM on week 1, 80% on week 2, 75% on week 3 and 85% on week 4. On the weeks where the load was reduced, another component of fitness would likely be increased in intensity.

Daily undulating periodisation

With daily undulating periodisation, volume and intensity changes take place within a single training week. For example, if your training intensity on week one is supposed to be 80% of 1RM and you have two squat sessions that week, in a linear approach you would use 80% loads for both sessions; with daily undulating periodisation, you might use 75% for one session and 85% for your other session. This approach allows for heavier and lighter training days and is useful when an athlete has multiple training sessions in a day, because trainings can be placed so that one component of fitness is prioritised in terms of intensity on one day, then gives way to another component of fitness on a subsequent day.

How do Linear and Non-Linear Approaches Compare in the Research?

A literature review by Nuckols (2018) looked at the results of 27 studies comparing the effects of periodisation of resistance training on both trained and untrained populations and reported the following findings:

- Overall, periodised resistance training programmes were more effective than non-periodised approaches with average weekly strength gains of 1.96-2.05% (compared to 1.59-1.70% in non-periodised studies).

- Overall, undulating periodisation approaches lead to weekly strength gains of 2.37-2.59% per week compared with linear periodisation approaches (1.90-1.96%). On average, undulating groups gained strength about 17% faster.

- Untrained populations gained strength faster than trained populations (2.53-2.7% a week vs 1.64-1.70%). Untrained subjects on a periodised programme gained strength 17.5% faster than those on non-periodised approaches.

- In untrained populations, linear and undulating approaches produced the same results in strength.

- In trained populations, those who used undulating periodisation approaches gained strength 28% faster than those working with linear approaches.

Interestingly, when looking at upper vs lower body exercise, all studies showed a bench press strength increase of 1.35% per week using periodised approaches, compared to just 0.87% per week in non-periodised approaches (55% better), however for squat the results were almost identical for periodised vs non-periodised approaches (1.87% vs 1.83%). Overall, undulating approaches led to 265% faster strength gains in bench press (over non-periodised approaches), but both approaches showed similar responses for squat.

Maintenance Programmes

A linear periodisation approach is most aligned with athletes who need to peak for single events or acute phases of competitions, like tournaments. You can also use this perodisation approach in early preparation phases of team sport athletes. The reality is that most team sport athletes have competitive seasons that last between 17 and 35 weeks of the year. Ensuring athletes peak at the beginning of the season and sustain that level of performance throughout the extended duration of the season presents a considerable challenge for trainers.

The trainer needs to track training volumes according to the amount of match play that various athletes engage in during competitive fixtures. They must also work around the recovery requirements of athletes involved in contact sports, who may need to prioritise healing over conditioning at regular points of the season. In summary, maintaining athlete condition throughout an extended season can be a challenging task.

Multiple studies have reported reductions in measured conditioning factors during the competitive season, which indicates it is very difficult to maintain all aspects of athlete conditioning as the season progresses. The likely cause of these decrements in condition is the inability to complete all aspects of training as prescribed due to residual effects of competition, injury and the schedule of competition. This highlights the importance of achieving the best physical condition possible as athletes enter the competitive season and also the value of non-periodised training approaches in-season to allow for greater coverage of training components (leading to improved maintenance). The flexible nature of undulating approaches also means trainings can be adapted at short notice to accommodate athlete recovery or availability issues. For this reason, a daily undulating periodisation approach is commonly used by trainers in the competition phase.

Turner (2011) suggests that a resistance training frequency of twice a week appears ideal (and realistic) for maintenance of resistance training gains during the competition training phase. However, including even two meaningful strength and conditioning sessions a week with team sport players involved in regular competition may prove difficult.

An example of a senior rugby league player at an amateur level can be seen in the following table:

| Monday | Power Session |

| Tuesday | Team Training |

| Wednesday | Strength Session |

| Thursday | Team Training |

| Friday | Rest (mini taper) |

| Saturday | Game Day! |

| Sunday | Active Recovery |

Tapering

As an athlete prepares to transition into the competitive season (or is in the final weeks before a major competition event, the usual practice is to reduce training volume so that the effects of fatigue are minimised entering the critical events. This reduction in training volume is known as tapering.

Turner (2011) reports the following resistance training benefits of an effective taper:

- Up to 20% increase in neuromuscular function (translating to strength and power output)

- Increased serum testosterone levels of up to 5% (with a corresponding drop in cortisol) - suggests optimal repair, recovery and growth status.

- 10-25% increases in the cross-sectional area of muscle

- A 10% decrease in inflammatory markers (indicates less muscle damage present)

- Increased glycogen stores (17-34%) - however, energy intake should be reduced to match energy requirements of taper activity levels

- Decreased sleep disturbance

These results all suggest a neuromuscular system that is in top shape to begin a competitive event or series of events.

ASCA (2022) suggests that when tapering volume for peaking sports or when nearing the competition phase, trainers should ideally use the following approach in their programming:

- Gradually reduce workload across at least one month (preferably longer) by 30-70%. Typically, a reduction of between 10-30% per mesocycle is appropriate.

- Two steps (mesocycles) to taper appears to be better than a single mesocycle taper.

- The suggested approach is to reduce volume across 3 or 4 weeks, increase volume again slightly for 1-3 weeks, then reduce volume again for 3-4 weeks.

Other Common Tapering Approaches

Turner (2011) describes four main approaches to tapering:

- A Step Taper: Involves an immediate and abrupt decrease in training volume, for example decreasing the volume load by 50% on the first day of the taper and maintaining this until the competitive event.

- A Linear Taper: Involves gradually decreasing the volume load in a linear fashion, for example, by 5% of the initial volume every workout from the start of the taper to the competitive event.

- The Exponential Taper: This involves decreasing the volume at a rate proportional to the previous session, for example, reducing volume by 5% of the previous session’s volume and continuing to do this for every session until the competitive event.

- The Two-phase Taper: Involves a linear decrease in volume, followed by a moderate increase in the final days of the taper (not as well studied).

Exploring Optimal Tapering Strategy

Bosquetet et al (2007) performed a meta-analysis on this very subject examining 27 research articles. The results of this paper revealed that the optimal taper duration is about 2 weeks and consists of exponentially reducing the volume of training by 41-61%, while maintaining the intensity and frequency of sessions. This finding was supported in a systematic review and meta-analysis by Wang (2022) who suggested current evidence indicated that a taper of between 14-20 days that reduces training volume by 41-60% (while maintaining intensity and frequency) was the most effective approach.

Measuring volume

Periodisation is all about manipulating the volume and intensity of training. Measuring the volume and intensity of cardiovascular training is relatively straightforward, involving the use of distance for volume and heart rate tracking for intensity. However, assessing resistance training volume is not as straightforward. While we can calculate the total weight lifted and utilise a percentage of 1RM to indicate intensity, a simplified approach for attributing volume to sessions while accounting for intensity would be ideal. This way, training loads can be easily prescribed, progressed, or adjusted as needed. Fortunately, a simple solution exists—let’s look at the RPE method for measuring training load and the concept of "Training Units."

Training Units

The following information is taken from the Australian Strength and Conditioning Association Coaching Manual (2022):

The Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) method of calculating training loads is a simple tool that coaches and athletes can use to monitor training load and help establish what normal, load, and de-load training volumes should be (particularly when access to monitoring equipment is limited, or the squad size is large and includes players of varying degrees of condition).

The RPE method uses a combination of the athlete’s Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) for a given session and the duration of the training session to allocate training units to each session. Here’s how it works.

The trainer (or athlete) rates the session in terms of intensity using the 1-10 Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale (below). They then simply multiply the rating they chose for the session by the session length.

The rating chosen by the coach or athlete should align with the resistance level associated with the workout.

Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale

| 0 | Rest |

| 1 | Really easy |

| 2 | Easy |

| 3 | Moderate |

| 4 | Sort of hard |

| 5 | Hard |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Really hard |

| 8 | |

| 9 | Really, really hard |

| 10 | Maximal |

See the following example of this system in use.

A client completes a muscular endurance session and rates it an 8 out of 10 in terms of intensity. The session was 45 minutes long. The calculation of training units would be as follows:

45 mins x 8 (RPE) = 360 training units

Note: For resistance training, the entire session must be included in the RPE choice, including rest periods. For example, a 5 x 5 strength session is tough when lifting, but involves significant rest, when compared with a hypertrophy super-set session).

The following is an example of the RPE method being used to monitor the training loads of an amateur athlete across a week. You can see that the athlete has a total of 2010 training units to complete across the week.

Note: This approach can be used for both cardiovascular and resistance training sessions and reflects total training volume.

| Type | RPE | Duration | = Unit Load | Daily Load | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | Upper body strength | 6 | 40 | =240 | 660 |

| ES Endurance/skill | 7 | 60 | =420 | ||

| Tuesday | Lower body strength | 5 | 40 | =200 | 450 |

| Skill/tactical | 50 | =250 | |||

| Wednesday | OFF | 5 | 0 | ||

| Thursday | Whole body strength | 4 | 40 | =160 | 360 |

| Speed/skill/tactical | 4 | 50 | =200 | ||

| Friday | Skill/tactical | 5 | 60 | =300 | 540 |

| ES Endurance | 8 | 30 | =240 | ||

| Saturday | OFF | 0 | |||

| Sunday | OFF | 0 | |||

| Weekly Total | 2010 | ||||

Source: ASCA Accreditation Manual

Once you have established the training units for a week, this method can then be used to apply progressive overload strategies for the following microcycle by simply adjusting the programme and adding up the new training unit total, you can check to see whether the increase in training units is in line with best practice for progressive overload (e.g. 5-10%). This is a simple technique to show how total training volumes have been applied through different phases of training.

This technique can also be used to determine the volume for “load” and “de-load’ microcycles. As discussed previously, load and de-load weeks require volume increases or decreases of up to 25%. A trainer then simply needs to calculate the training units required for this increase and then adjust either the exercise intensity, volume (or both) to achieve this increase in units.

For example, in the case of the athlete’s training week, a 25% increase in training load would require the addition of 502 training units (25% of 2010). This could be achieved by adding another session on either a Wednesday or a weekend day or by adding to the duration (or intensity) of existing sessions by manipulation of training variables. Conversely, for a de-load week, this athlete would need to complete 502 less training units. This approach could also be used to determine training loads during a taper.

If this method is used from the start of the training year, weekly training loads can be monitored across the preparation phases and then used to calculate the rate of a taper and to determine the total training volume of the competition phase of training. As competitive games will be included in the RPE method, this will guide the allocation of training units required in a given week (and will of course lead to a reduction in training volume. When using a daily undulating approach, these training units can then be allocated across hard and easy training days as the trainer sees fit.

Professionals vs amateurs

While the periodisation process can be used for athletes at different levels of competition, total training volume is one of the key differences between amateur and professional athletes. This is because professional athletes have more time to devote to their training and recovery. This means they often complete multiple training sessions a day. They also have a higher training age, so are able to complete more volume (or maintain higher intensities) of training. Professional athletes typically also have more prolonged and structured preparation periods than amateur athletes, so are able to attain higher levels of condition in this training phase. The bottom line, professional athletes can handle greater training loads. The following is an example of a professional AFL athlete’s weekly training units vs our amateur athlete above.

Amateur

| Type | RPE | Duration | = Unit Load | Daily Load | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | Upper body strength | 6 | 40 | =240 | 660 |

| ES Endurance/skill | 7 | 60 | =420 | ||

| Tuesday | Lower body strength | 5 | 40 | =200 | 450 |

| Skill/tactical | 50 | =250 | |||

| Wednesday | OFF | 5 | 0 | ||

| Thursday | Whole body strength | 4 | 40 | =160 | 360 |

| Speed/skill/tactical | 4 | 50 | =200 | ||

| Friday | Skill/tactical | 5 | 60 | =300 | 540 |

| ES Endurance | 8 | 30 | =240 | ||

| Saturday | OFF | 0 | |||

| Sunday | OFF | 0 | |||

| Weekly Total | 2010 | ||||

Source: Adapted from ASCA Accreditation Manual

Professional

| Type | RPE | Duration | = Unit load | Daily load | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | AM | Upper body strength | 6 | 45 | =270 | 900 |

| PM | ES Endurance/skill | 7 | 90 | =630 | ||

| Tuesday | AM | Skill/tactical | 6 | 70 | =420 | 720 |

| PM | Lower body strength | 5 | 60 | =300 | ||

| Wednesday | RECOVERY | 0 | ||||

| Thursday | AM | Speed/skill/tactical | 5 | 70 | =350 | 650 |

| PM | Whole body strength | 5 | 60 | =300 | ||

| Friday | AM | Skill/tactical | 4 | 60 | =240 | 720 |

| PM | ES Endurance/tactical | 8 | 60 | =480 | ||

| Saturday | AM | Skill/game simulation | 6 | 90 | =540 | 540 |

| PM | - | |||||

| Sunday | OFF | 0 | ||||

| Weekly Total | 3530 | |||||

Source: Adapted from ASCA Accreditation Manual

Important

It's crucial to acknowledge that amateur and youth athletes cannot safely handle or sustain the training loads seen in professional athletes. Therefore, it's strongly advised not to attempt training them with such elevated levels of training volume.

Considerations for amateur athletes

ASCA (2022) suggests that for professional seasonal regular fixture sports like rugby, netball, basketball etc, the in-season workloads should be about 50-70% of the highest workloads (including competitive games) achieved in the preparation phase of training. This allows the athletes to train, travel, play, and recover. However, because amateur athletes typically don’t achieve the high training loads of professional athletes during the preparation phase, they may be best to try and maintain 80% of the preparation load in-season (including games).

ASCA (2022) suggests a typical in-season training load for many seasonal team sport athletes is a 1900 weekly training unit load. For this to represent 60-70% of their preparation training volumes, they should have attained 2700-3000 training units in the peak of their preparation training phase. However, it is very difficult for amateur or youth athletes to attain higher than 2500 weekly training units alongside full-time work, family or study commitments. This is why in-season loads for amateur athletes tend to be set at 80% of their preparation phase loads (including games). This is because the time an amateur is able to devote to training is likely very similar in both preparation and competition phases.

ASCA (2022) also suggests that amateur athletes with 1500 training units a week (in addition to competitive games) will struggle to recover in time for competition games.

A comparison of weekly training units between a professional AFL player and an amateur rugby player in the competition training phase is compared in the following table.

Given that the professional player has more time to train and has a higher training volume threshold, they are able to achieve greater training volumes weekly. While the professional player completes more training units, it is still a relevant percentage of their higher training units achieved in their preparation training phase (approximately 70%). The amateur player cannot devote as much time to training and has not achieved the same volume of training in the preparation phase, so maintains training volume at around 80% of preparation phase peak volume.

Amateur Rugby Athlete in-season

| Type | RPE | Duration | = Unit load | Daily load | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | AM | Recovery | 0 | |||

| PM | ||||||

| Tuesday | AM | Whole body strength | 4 | 50 | =200 | 320 |

| PM | Skill/tactical | 3 | 40 | =120 | ||

| Wednesday | AM | ES Endurance/tactical/skill | 4.5 | 80 | =360 | 360 |

| PM | ||||||

| Thursday | AM | OFF | 0 | |||

| PM | ||||||

| Friday | AM | Whole body/power/speed | 4 | 60 | =240 | 240 |

| PM | ||||||

| Saturday | AM | Skill/game simulation | 3.5 | 40 | =140 | 140 |

| PM | ||||||

| Sunday | Game | 8 | 90 | 720 | ||

| Weekly Total | 1780 | |||||

Source: Adapted from ASCA Accreditation Manual

Professional AFL Athlete in-season

| Type | RPE | Duration | = Unit Load | Daily load | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | AM | Recovery | 0 | |||

| PM | ||||||

| Tuesday | AM | Strength | 4 | 50 | =200 | 380 |

| PM | Skill/tactical | 3 | 60 | =180 | ||

| Wednesday | AM | ESE/tactical | 5 | 90 | =450 | 0 |

| PM | ||||||

| Thursday | AM | Skill/tactical | 4 | 80 | =320 | 520 |

| PM | Power | 4 | 50 | =200 | ||

| Friday | AM | Skill/tactical | 4 | 60 | =240 | 240 |

| PM | ||||||

| Saturday | AM | Tactical/game simulation | 4 | 45 | =180 | 180 |

| PM | =800 | |||||

| Sunday | Game | 8 | 100 | 8000 | ||

| Weekly Total | 2570 | |||||

Source: Adapted from ASCA Accreditation Manual

For trainers working with amateur athletes, most literature suggests the following guidelines:

- No more than 2000 training units a week (including the game). Given that games can absorb as much as 700 units (e.g. an 80-minute game of rugby at an 8RPE rating = 80 x 8 = 640 units), this leaves around 1200-1400 training units for the rest of the week.

- Preparation loads no more than 2500 training units a week (peak volume)

Let’s take a look at the following resistance training approaches and the basic periodisation for each.

- Muscular endurance

- Hypertrophy

- Strength

- Power and plyometrics.

Where does muscular endurance fit into a periodised plan?

In general terms, muscular endurance would most often be introduced in the general preparation phase of a periodised programme. This is where an athlete is working on general conditioning. Because muscular endurance training has high volume associated with it, this is best done earlier in the training schedule. Muscular endurance can also be trained hand in hand with aerobic and anaerobic capacity training which are common features of the general preparation phase. Remember also, that due to the lighter loads used in muscular endurance training, this type of resistance training serves as an ideal pre-cursor to ready the body for heavier and more explosive lifting in the later stages of general preparation and specific preparation phases.

In terms of periodising muscular endurance, it would be usual to start with lower loads, moderate endurance repetitions, and fewer sets and build volume over the initial weeks of general preparation. Exercise selection will initially revolve around large muscle, multi-joint exercises, but may become more targeted to muscle movements in competition during the specific preparation phase.

It would also be a typical approach to work through long-term muscle endurance in the early stages of general preparation, then move towards short-term muscle endurance and finally power muscular endurance as exercise intensity is raised and volume starts to decrease (end of specific phase and start of competition phase).

Ultimately, the exact placement of muscular endurance in the periodised training plan will be dependent on the athlete and the sport they play. Sports like rowing, cycling, AFL and football, have higher needs for sustained muscular endurance than a sport like volleyball or tennis which are all about short repeated high intensity efforts. The sports mentioned first would likely continue to work on muscular endurance throughout the competitive season, whereas other sports will have other modes of training like power and speed as their primary focus during competition phases.

Where does hypertrophy (gaining muscle) fit into a periodised plan?

This will ultimately depend on the athlete and their goals, the sport they play and the time they have to devote to different forms of training. Hypertrophy may be targeted by athletes who need to increase mass to better deal with contact situations (e.g., a young rugby player about to move from school to senior rugby, a combat sport athlete wanting to go up a weight class, or a basketballer looking to become more physically dominant). It may also be used to develop musculature around a recently injured site that may have undergone atrophy during the recovery process.

In general terms, hypertrophy training would be placed in the early part of the general preparation training phase and last up to 6 weeks. Hypertrophy training would only be present in the periodised plan of an athlete who had a goal of developing more lean body mass for the upcoming season. The reason for placing hypertrophy training in the general preparation mesocycle is because of the high-volume demands associated with this type of training (meaning it is prudent to perform this training away from competition). It could also be considered for the off-season phase if there is a considerable break between the end of one season and the start of the next.

Due to the high recovery requirements associated with hypertrophy training it would be a good idea to avoid other high intensity training modes, so this training could be scheduled in conjunction with something like low intensity cardio training. Hypertrophy training will often progress into a strength phase and is a nice progression phase to move towards strength training from a muscular endurance block. In fact, many athletes with shorter off-seasons will alternate between strength and hypertrophy training throughout their general preparation phase.

In terms of periodising hypertrophy training, it would be usual to start with lighter loads and a 10-12 repetition count and move towards heavier load and lower repetition counts. A few weeks into the programme it would be beneficial to begin to bring some variety to hypertrophy sessions to shock the muscle. The great news is there are lots of different hypertrophy training approaches to use.

The hypertrophy phase of training will be relatively short for most athletes. As the athlete moves into their specific preparation phase other forms of training more related to the requirements of their sport will take the place of hypertrophy.

Where does strength training fit into a periodised plan?

Strength training forms the basis for many other forms of training (like speed and power), so is often found in the preparatory phases of periodised programmes, giving way to more explosive training in the specific and competition preparation periods of training. That said, some athletes may continue to work on strength throughout the competitive training phase, albeit in a reduced (maintenance) fashion.

In a preparation phase with limited time for development of maximum strength, strength will typically be targeted in the general preparation phase when there are no competitions, and technical, tactical, or sport-specific work is limited. According to the National Strength and Conditioning Association of America (NSCA), The central goal of this period of training is to develop a base level of conditioning in order to increase the athlete’s ability to tolerate more intense training. Often the early preparatory phase will begin with more moderate loads and moderate repetition numbers to ready the body for higher loading. This means the general strength phase will likely fall towards the end of general preparation. These strength exercises will move from a more general approach to one that relates more specifically to the sporting demands. The average intensities used in the maximum strength mesocycles will be higher (85%+ of 1RM). A typical strength focus would be completed over around 6 weeks in a time-crunched schedule.

Gamble (2009) suggests there are four key phases that can be applied to strength training across a periodised programme. These include anatomical and neuromuscular adaptation, hypertrophy, maximum strength, conversion to sport-specific strength, and maintenance. The duration of each of these phases will again be dependent on the length of the preparatory phase available. Anatomical and neuromuscular adaptation and hypertrophy phases will often occur in the early part of general preparation, where athletes are lifting higher volume, moderate loads. A maximal strength phase will likely be placed at the end of general preparation and will involve heavier loads with less volume. A move to sport specific strength conversion will occur in the specific preparation phase where the exercises chosen will have more relevance to specific needs of the sport. This will often include a move towards more unilateral exercises and contrast training approaches (mixing strength lifts with power/explosive movements). Maintenance will be targeted in the competition phase of training and will involve sessions of high intensity by lower volumes and durations.

Frequently, the range of motion is adjusted to better mimic sport-specific movements. For instance, a volleyball player may transition from a full squat to a half squat, or a squash player may shift from a linear lunge to a lateral lunge.

Where do power and plyometric training fit into a periodised plan?

In a general approach for most team sport athletes, power training will be introduced towards the end of the general preparation phase and continue through the specific preparation phase and into the competition phase.

Power training should follow a block of general strength training and it is most common to start the transition to power training with higher force/lower velocity training before shifting the focus to reducing load and increasing speed of movement as we move through the specific preparation phase.

Peak velocity training methods (like plyometrics) would typically be used in the competition phase in conjunction with peak power and speed-strength training (often in a contrasting approach).

Plyometric training should follow the same pattern of progression each time it is introduced in a periodised programme. It should always begin with landing drills and explosive concentric contractions, then progress to counter-movement exercises, multi-direction drills, and finally shock inducing exercises (e.g. depth jumps). The speed at which a client moves through these phases will be highly dependent on their training age and history of training with these forms of exercise.

As the competitive phase continues, plyometrics should begin to show more specificity to the demands of the sport the athletes play. If the client desires more general power production improvements (i.e., not a sports athlete), then phases could be cycled by returning to a more strength-focused approach for a short time and then working through the progressions again (or using contrast methodology).

Many trainers will opt for a contrast (strength/speed) session earlier in the week (to help maintain strength) and a plyometric approach later in the week. In the competition phase, sessions will be shorter but performed with high intensity.

Now that you have a more detailed understanding of the periodisation process and where each training mode fits within a periodised annual plan, it is time to learn the process of developing a periodised annual training calendar for a sporting client. This requires you to use a periodised plan annual plan template.

Introducing the periodised plan template

Every good periodised plan has an annual plan overview template. The overview template can take many forms depending on what details you would like to show, but the essential components of a good overview template are:

- The competition dates – these can be simply listed or may be identified in terms of importance.

- The training phases and their start and finish dates.

- The mesocycle selections and durations.

- The components of fitness being targeted in each mesocycle (purpose).

- The volume and intensity of training throughout the programme.

Some coaches or trainers will also include the key physical testing dates across the year and indicate the importance of different aspects of training across the year, e.g. technical, tactical, physical, and psychological skills.

Some periodisation plan templates can be very simple like the following example, click on the arrows beneath the image to view each template. The images are of the following templates

- Periodisation- Football (Soccer)

Image source: https://pdhpe.net/improving-performance/what-are-the-planning-considerations-for-improving-performance/planning-a-training-year-periodisation/develop-and-justify-a-periodisation-chart/ - Rugby Specific Training

Image source: https://rugbyscientists.com/2013/11/01/year-round-strength-conditioning-for-rugby-union/ - Academy Annual Plan (this template includes more detail)

Image source: https://simplifaster.com/articles/periodization-academy-rugby-players/ - Yearly Plan Template

Image source: https://www.fasttalklabs.com/articles/how-to-develop-a-yearly-training-plan/

The following template is a periodisation session plan that you can download and save for your own personal use.

You can populate it by:

- entering the months and the first date of each week.

- Indicating where the key competition occurs (where you want to be peaking) These can be colour-coded in terms of importance.

- Merge cells together to label and show the duration of training periods and mesocycles.

- Merge and colour cells to represent where in the programme resistance training components of fitness are targeted.

- Use coloured lines to indicate how the volume and intensity of exercise change over the training periods.

Click to download: Periodisation Plan template

Here is a completed template that you can use as an example:

Click to download: Periodised plan Athlete example

Right, time to apply what you have learned. Head to your assessment for an assessment guide video and instructions on submitting your assessments.

The assessment guide video explains your assessment task, which requires you to use the information you have learned on this topic to design a periodisation plan for an athlete. This assessment will require you to apply the knowledge you have learned and practised by completing the following tasks:

- Select an athlete and provide a brief profile of them

- Give a basic overview of the seasonal requirements of your athlete’s sport

- Identify three muscular demands of your athlete’s sport

- Create a year-long periodisation resistance training plan for your athlete)

- Provide an overview with clear rationale for the periodised plan you created