Visual storytelling is a cornerstone of animation, weaving together narrative elements with captivating imagery to convey stories that resonate with audiences. In this comprehensive topic, explore nine key areas, each offering valuable insights and techniques necessary to animate your final sequence.

Trace the origins of storyboards through to creating your own story concept, ultimately crafting a storyboard that vividly communicates your creative vision. Delve into film techniques and influences, equipping yourself with the knowledge necessary to infuse vitality into your storyboard. Get ready to unlock the secrets of visual storytelling and unleash your creative potential in the world of animation.

Subtopics that you can explore

In this Visual Storytelling topic, you’ll explore nine subtopics, each offering valuable insights and techniques to enhance your animation skills. These subtopics are:

- Storyboarding Origins and Types

- Film Techniques

- Film Influences and Film Study

- Academic Writing Essentials

- Story Concept Development

- Storyboard Formatting, Flow, and Engagement

- Geography

- Drawing Storyboards

- Fundamental Narrative and Storytelling Concepts

Learning tasks that will help you develop and practise animation skills

Practice

Use your skills and build your knowledge

Dive into this topic’s learning tasks confidently – they're your stepping stones towards getting to grips with essential visual storytelling techniques. Completing these tasks will hone your skills in crafting compelling narratives and creating impactful storyboards.

Look out for this PRACTICE box throughout this topic to identify learning tasks and resources, letting you know exactly what to do. The following information outlines what learning tasks to expect in Visual Storytelling and how much time you should allocate to each one.

| # | Learning Task Name | Duration (Hours) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify three types of shots | 0.5 | |

| 2 | Identify camera movements from A Bug’s Life | 0.5 | |

| 3 | Identify composition techniques used in three shots | 0.25 | |

| 4 | Create a list of your ten favourite films | 0.25 | |

| 5 | Create a reference board of key shots from two favourite sequences | 0.5 | |

| 6 | Explain aspects of key shots from your reference boards | 1 | |

| 7 | List your observations from the opening sequence of Brave | 0.25 | |

| 8 | Write an introduction for your Brave film study | 0.5 | |

| 9 | Write paragraphs on film techniques and visual elements for your Brave film study | 2 | |

| 10 | Source quotes for your Brave film study | 1.5 | |

| 11 | Fine-tune and complete your Brave film study | 2 | |

| 12 | Generate three simple story ideas | 1 | |

| 13 | Write a short synopsis for one of your ideas | 2 | |

| 14 | Draw a short sequence of storyboard panels for a story idea | 2 | |

| 15 | Draw a storyboard for a script sequence from Room on the Broom | 16 | |

| 16 | Draw another storyboard for a different script sequence from Room on the Broom | 16 | |

| 17 | Create a series of storyboard panels for your story concept | 18 | |

| 18 | Complete story treatment components for Spirited Away | 3 | |

| 19 | Explain the three-act narrative structure of Spirited Away | 2 |

Feedback and support are woven through the learning tasks as you complete them. Reach out if you have any questions about what to do!

Explore the origins of the storyboard, find out how it functions as a crucial story development tool, and learn about the various storyboard types used across different mediums.

Origins of storyboarding

The storyboard has its origins in gag strips drawn by animators when they began their animation.

In the 1930s, Max Fleisher had these gag strips cut out as individual panels and stuck on a wall where they could be viewed in sequence by the animation team. The team could arrange the panels differently and draw additional panels where required.

Walt Disney implemented and developed that approach in his studio. It became fixed as a part of the production process.

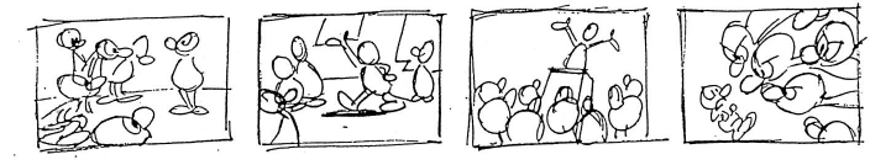

![[ADD IMAGE'S ALT TEXT]](/sites/default/files/Disney%20Storyboard.png)

Many film production companies adopted the storyboard in the 1930s. It was used as a blueprint that allowed all the people working on a production to share a vision of the story. In this way, a storyboard also served as a detailed schematic for animation production.

How does storyboarding function as a story development tool?

Developing a storyboard often involves several pitch sessions with the production team and the director, where the storyboard artist presents their drawn ideas for feedback and discussion.

Storyboards are not all developed by first writing a script.

In our studio, we don’t write our stories, we draw them.Walt Disney (animator, film producer, entrepreneur)

Storyboards can be used in a basic way to put pictures to an existing script – a common approach in television streaming services (TV) feature animation where cost and efficiency, and not necessarily great stories, are the driving factors.

But this doesn't represent the main way a storyboard functions in animation as a story development tool.

In animation, storyboarding has always been and is still used mainly to develop the story.Eric Goldberg (animator, film director and producer)

![[ADD IMAGE'S ALT TEXT]](/sites/default/files/Ballet-Oop.png)

Storyboard types across mediums

Today, storyboards are used for most film, television, commercial, and gaming projects. However, each of these mediums uses storyboards in slightly different ways.

In general terms, a storyboard can be defined as either:

- a sequence of pictures that illustrates a story or

- a visual adaptation of a script.

Tip

Where communication trumps drawing skills

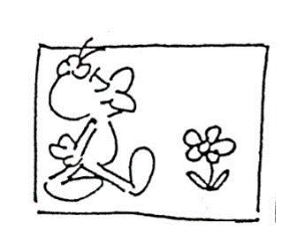

Did you know that a good storyboard artist doesn’t need to be great at drawing?

To be a good storyboard artist, you need to know how to effectively communicate with your storyboard.

It's important to learn storyboarding fundamentals, including visual storytelling concepts, staging and composition, clear labelling, and how to achieve continuity.

A thorough storyboard:

- clearly describes a story’s actions and events and each scene’s composition

- helps plan any camera moves

- provides visuals that reinforce a script's mood, atmosphere, and pacing.

While storyboarding conventions, terms and practices are variable from one medium to the next (e.g. live action versus animation), the basic information is much the same.

What are the features of different types of storyboards?

Select + to view features of storyboards for animation, live-action, and TV.

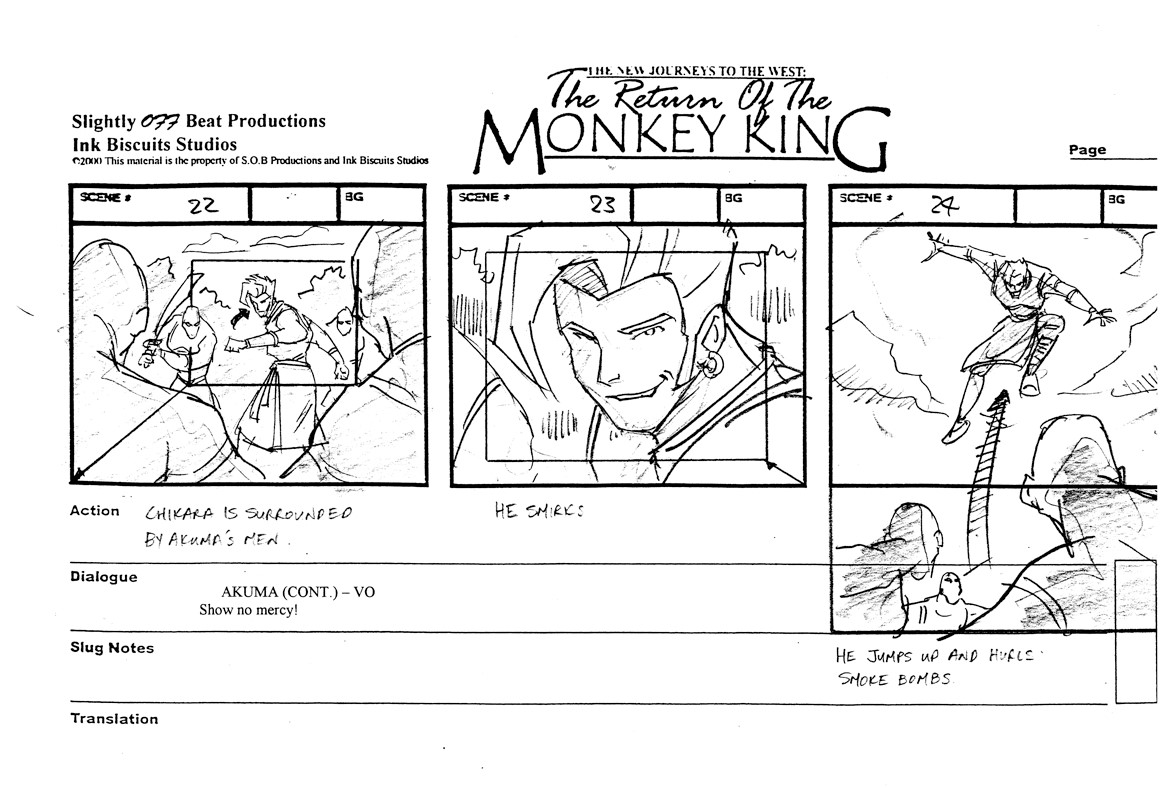

- An animation storyboard needs to be very thorough, describing every new action and expression.

- The storyboard artist determines camera angles. Once the storyboard is complete and approved, shots and camera angles stay largely unchanged.

- In animation, a 'scene' is the term used to describe each time the camera cuts to a new angle. The 'scene' ends when the camera cuts away to a new shot. For example:

- If the camera cuts from a medium shot to a close-up, this is considered and labelled as two different scenes on the storyboard.

- If, however, the camera moves closer in one continuous shot, this is considered and labelled as just one scene.

- A new scene is clearly indicated on the storyboard with the specific scene number in the upper left-hand box above each panel.

- Writing ‘CUT’ between panels can also indicate the end of a scene.

Live-action filmmakers commonly use storyboards to plan their films in great detail.

Swipe these two images to compare the live-action footage with the original storyboard panel:

TV storyboards are typically developed directly from polished written scripts, unlike feature film storyboarding (which is primarily used as a story development tool).

A TV animation scriptwriter considers many factors of producing animation, such as cost, efficiency, and tight TV production schedules. TV storyboard artists are driven as much by these factors as by more creative factors.

While TV storyboards might not be as valuable in your creative development as an artist, they are a fantastic training ground in many practical storyboarding processes, such as efficiently formatting, labelling and planning storyboards.

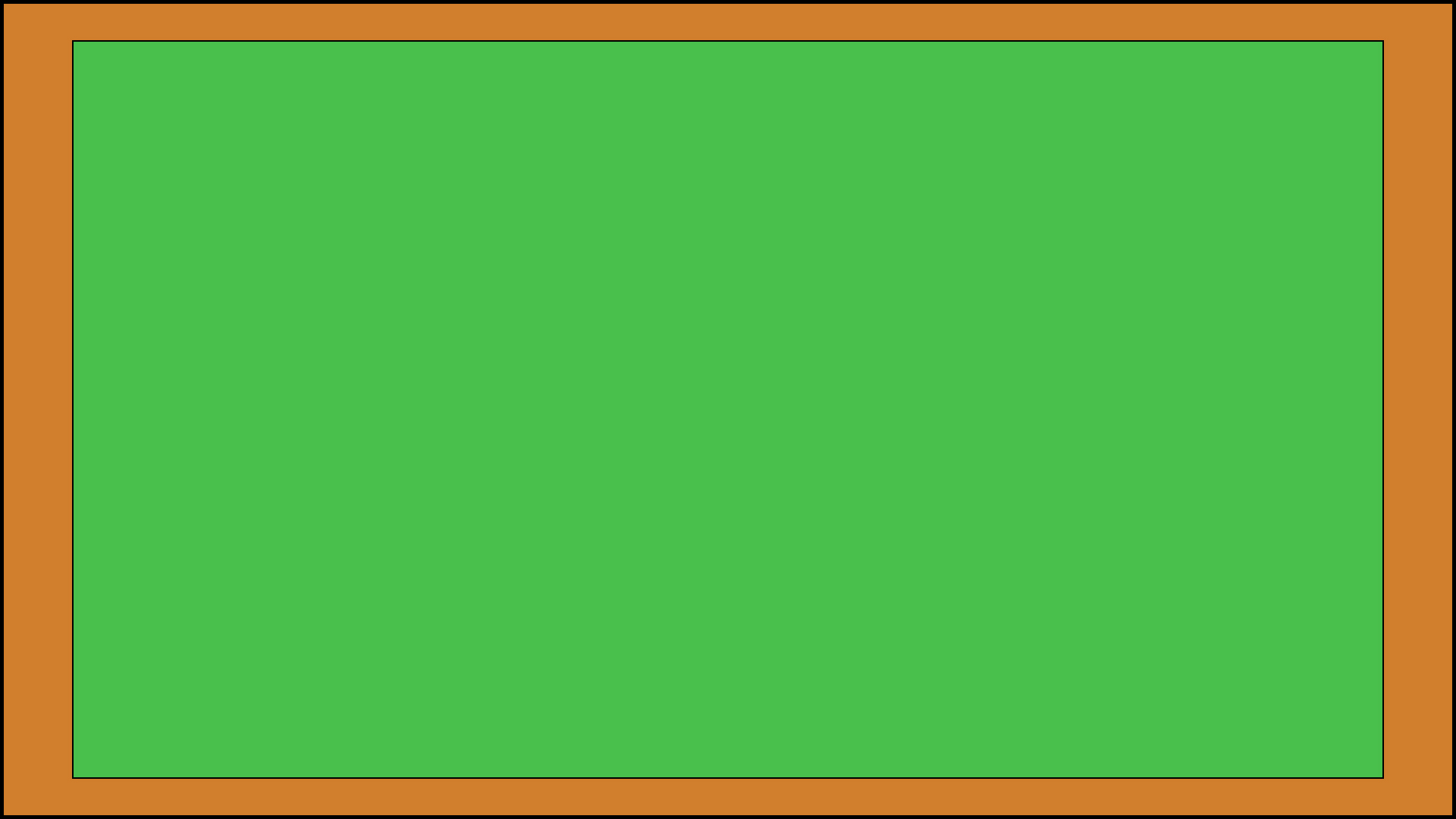

Get to know film techniques used in visual storytelling! Find out how shots, angles, and camera movements impact viewers and uncover how transitions and composition techniques add interest and appeal to visual storytelling.

Important

Use the Film Techniques worksheet

In this subtopic, you’ll practise three learning tasks:

- Identify three types of shots.

- Identify camera movements in a sequence from A Bug's Life.

- Identify compositional techniques used in three shots.

Note: You only need to post to Forum: Visual Storytelling once by using the same worksheet for all three tasks. Just follow these three steps:

- Download this Film Techniques worksheet.

- As you work through each learning task, record your findings in the corresponding section of the worksheet – don’t forget to save to your device as you go!

- After completing all learning tasks, upload your completed worksheet to Forum: Visual Storytelling for feedback.

You’ll get a reminder to use the worksheet in each learning task within this subtopic.

Types of shots

With storytelling, you can plan different shots for different reasons. Choosing a particular camera position and angle can:

- clarify the action, or

- establish a new setting, or

- enhance the mood or emotion in a scene.

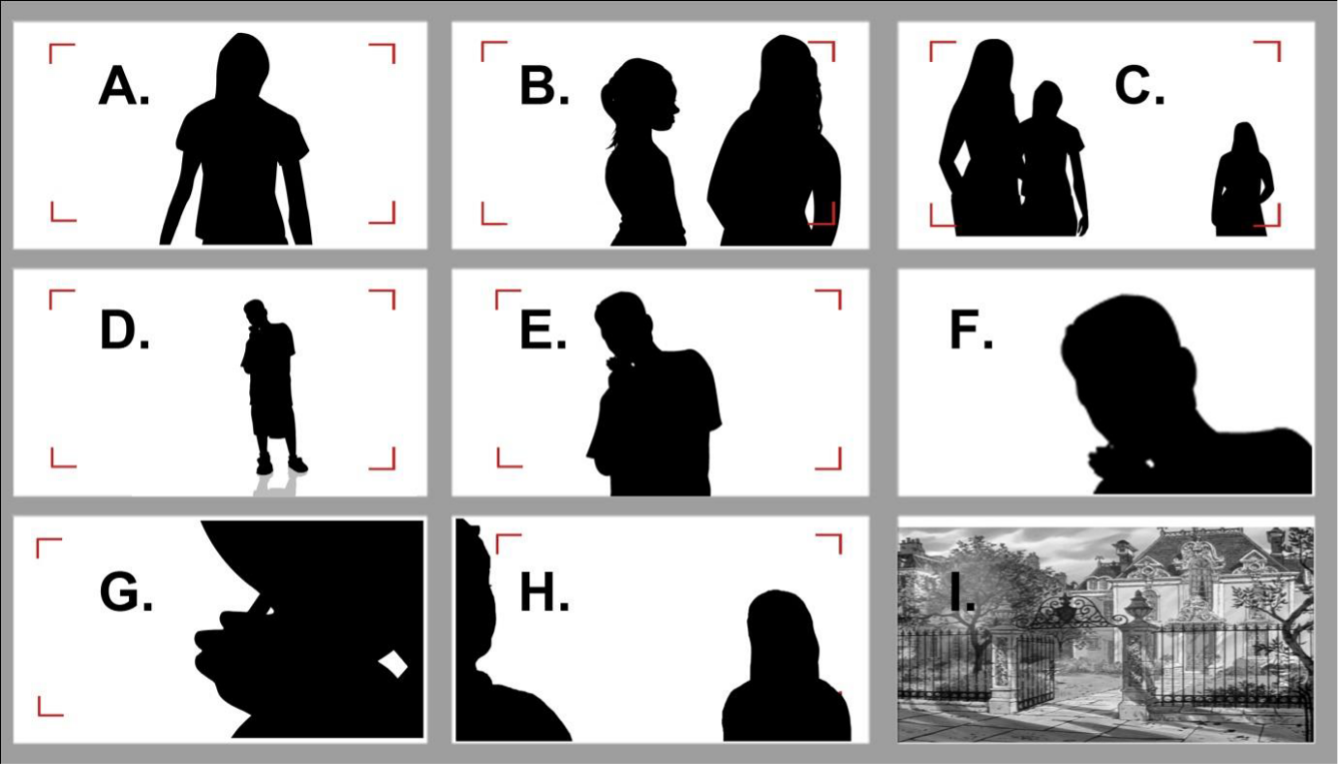

What are some standard shots?

- Look at this image of nine standard shots.

- Complete this nine-question quiz to test your knowledge of these standard types of shots.

Camera techniques

Understanding how to use camera techniques effectively in storytelling becomes intuitive if you see the camera as your viewpoint in the world.

Impact of shots on viewers

For example, take the extreme close-up shot. How does it make you feel to be extremely close to someone’s face?

An extreme close-up of someone’s eyes creates an intimate feeling. It focuses your attention on that person’s emotions and intentions.

Impact of angles on viewers

Camera angles can also affect an audience intuitively.

A low-angle shot (or upshot) creates a feeling in the viewer of being smaller or lower, a feeling we experienced as babies when our view of the world was always from a position of being small.

A high-angle shot has the opposite effect!

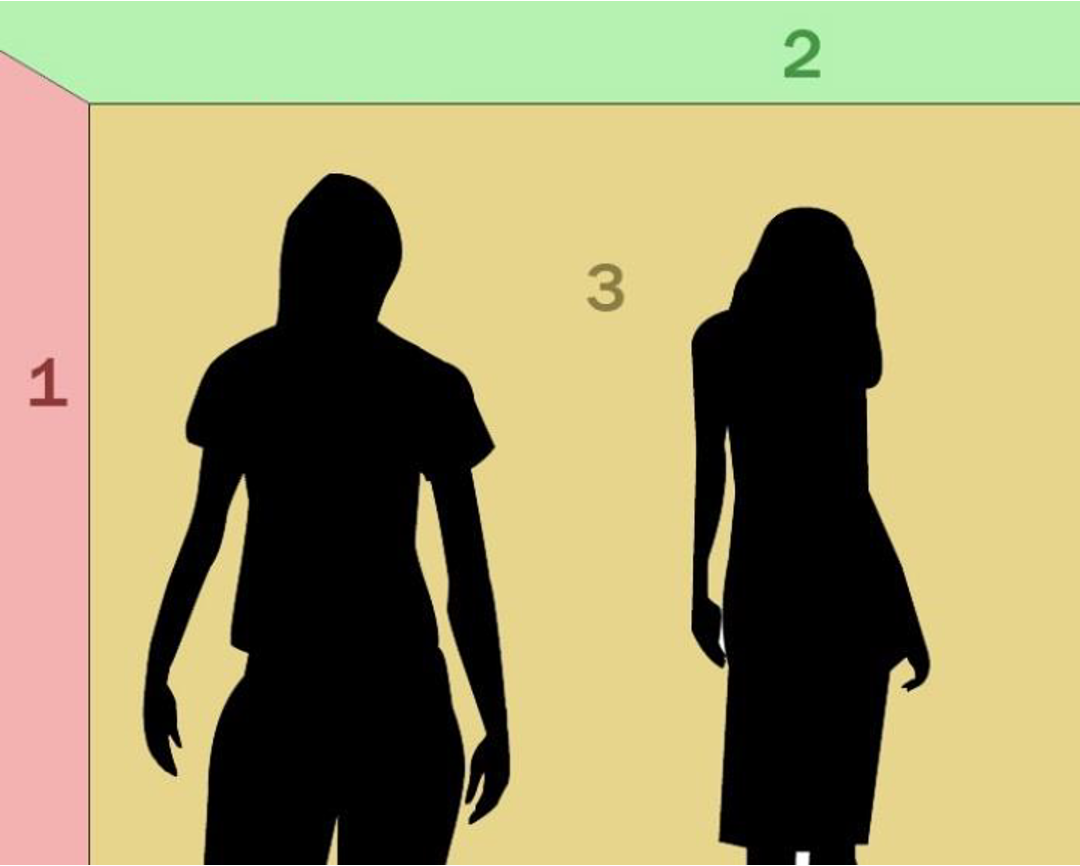

How does adding depth to shots impact storytelling?

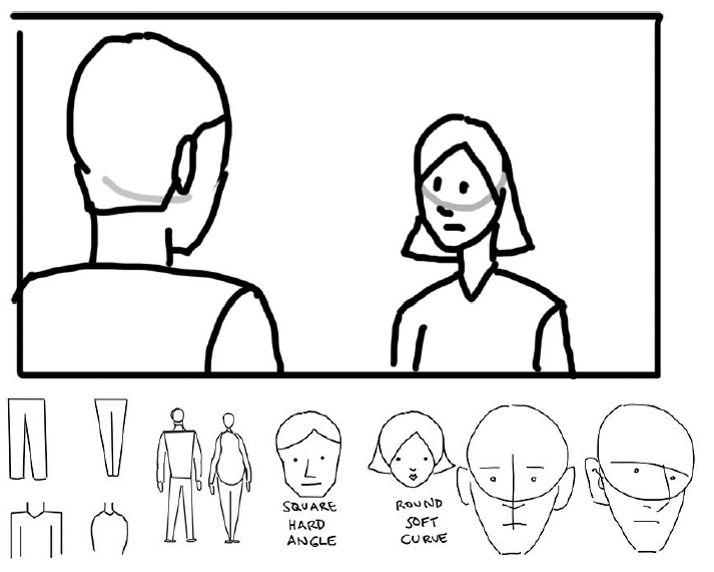

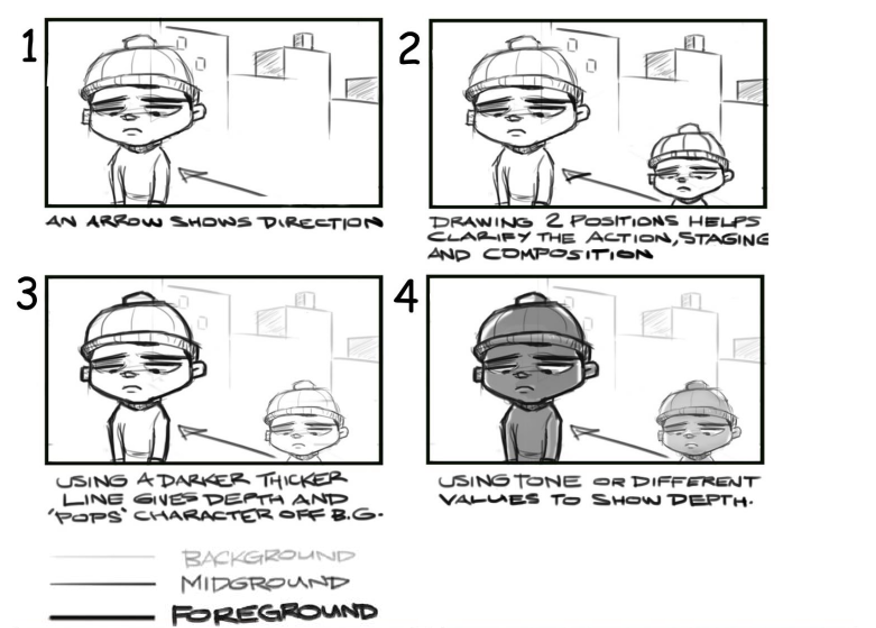

By using three planes to represent spatial perspective, you can enhance your visual storytelling by creating a sense of depth in the shot. Each of the three planes represents a 3D axis in the space, i.e. the X, Y, or Z axis.

In the following image, the shot has depth due to the characters being placed at different points along planes 1 and 3.

Swipe through these two images to see how increased depth between characters provides an enhanced space.

You should aim to stage shots in simple and natural ways, so reserve more dynamic shots for action sequences.

Practice

Task 1: Identify three types of shots

Knowing how to use different types of shots in your storyboards helps you enhance your storytelling. Can you identify the three shots below and explain their use in their films?

What tools or resources do you need for this task?

- Make sure you have access to the Film Techniques worksheet.

- Swipe through these three images to help you complete this learning task:

What steps should you take to complete this task?

30 minutes

Set aside up to 30 minutes to complete steps 1-4 below. Remember to save your work as you go when using Word.

- Download the Film Techniques worksheet.

- Examine each of the three shots above.

- Record in the corresponding worksheet section the following information:

- Identify the shot types (think about camera angles as well).

- Explain briefly why you think the shot types were used.

- Make any required updates to your Film Techniques worksheet and save to your device.

What should you do after completing this task?

Think about how shot types contribute to a scene's mood and reveal character details. How might using different shot types alter a viewer's perception and a scene's impact?

Now that you’re familiar with basic shot types and angles, it's time to explore how camera movements like pans and trucks enhance visual storytelling and add dynamism and depth to a scene.

Camera movements

The storyboard artist uses camera movements to help tell a story more effectively.

There are three types of camera movements you need to know:

- Pan

- Truck in

- Truck out.

Important

Camera jargon

The terminology used in animation for some camera movements below differs from that used in live-action filmmaking.

Select + for each camera movement’s description.

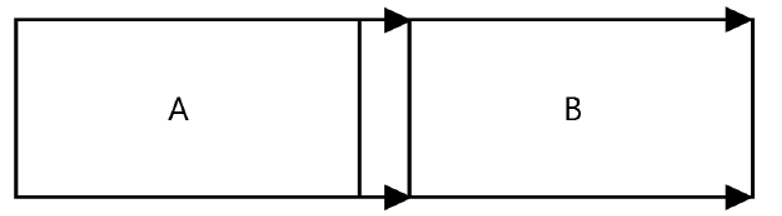

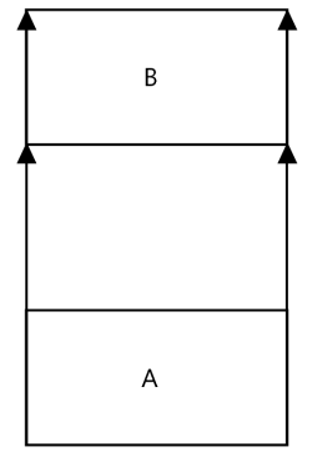

A pan is a camera movement used to follow action. The following images represent each of the three main types of pans:

i. Horizontal pan:

ii. Vertical pan:

iii. Diagonal pan:

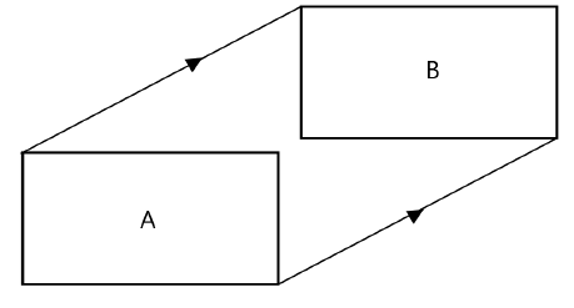

A truck in is a camera movement in which the camera moves into (i.e. closer to) the scene, narrowing the camera view and bringing the audience into a scene or situation:

A truck out is a camera movement in which the camera moves away from the scene, widening the camera view and bringing the audience out of a scene or situation:

Practice

Task 2: Identify camera movements from A Bug's Life

Understanding how different camera movements are used in film deepens your comprehension of visual storytelling. Can you identify specific camera movements in the A Bug's Life sequence below?

What tools or resources do you need for this task?

- Your saved Film Techniques worksheet.

- Swipe through these five images to help you complete this learning task:

What steps should you take to complete this task?

30 minutes

Set aside up to 30 minutes to complete steps 1-6 below. Remember to save your work as you go when using Word.

- Open your Films Techniques worksheet.

- Watch the short video (1:20m) above, which shows a sequence from A Bug’s Life.

- Rewatch the video and observe camera movements – such as pans, truck ins, or truck outs – used in the film sequence.

- Identify up to five specific camera movements used in the film sequence, as described in the five shots above.

- Record these five camera movements in the corresponding worksheet section.

- Make any required updates to your Film Techniques worksheet and save to your device.

What should you do after completing this task?

Consider how camera movements contribute to the sequence’s mood and enhance storytelling. How can you use various camera movements in your storyboard to plan and influence a viewer’s experience?

When you’re ready, move on to the next two sections, Transitions and Composition, where you’ll explore creative ways to transition between scenes and how compositional techniques enhance visual storytelling.

Transitions

The storyboard artist uses transitions between shots to help continuity and add interest. There are many creative ways to transition between scenes.

Commonly used types of transitions include:

- Fade in (FI)

- Fade out (FO)

- Cross dissolve (X-diss)

- Wipe

- Ripple dissolve

- Spin away.

Fade in and Fade out

Fade ins (FI) and fade outs (FO) are commonly used at the beginning of new scenes and to show the passing of time.

When one shot finishes with a fade out (to black), and the next begins with a fade in, the viewer feels like time has passed in the story.

Cross dissolve

A cross dissolve (X-diss) occurs between two scenes as one dissolves away, revealing the new scene.

The duration of a cross dissolve can be lengthened or shortened for different effects. A cross dissolve should be at least eight frames, or it can look like a mistake in editing.

The following image shows how to indicate a cross dissolve on a storyboard:

![[ADD IMAGE'S ALT TEXT]](/sites/default/files/Cross%20dissolve.png)

Wipe

A wipe involves one scene being pushed out of the shot, apparently by the next scene as it slides into place.

A wipe may occur horizontally or vertically.

The following image shows a creative wipe transition:

![[ADD IMAGE'S ALT TEXT]](/sites/default/files/Disney%E2%80%99s%20Super%20Goofy.png)

Ripple dissolve

A ripple dissolve is most commonly used to introduce flashbacks and dream or daydream sequences. It combines a ripple effect with the cross dissolve.

Spin away

The spin away is commonly used to introduce a newspaper headline. It has become linked with the iconic television series Batman.

Composition

Swipe through these four images to see examples of four composition techniques that enhance appeal and interest in visual storytelling.

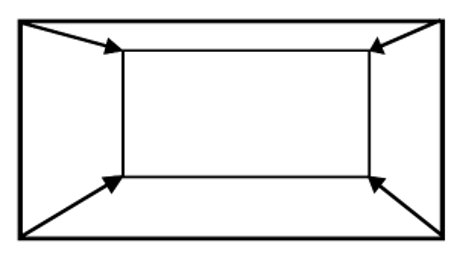

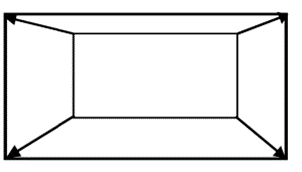

Framing

Framing draws attention inward towards the middle of the screen area, similar to how a picture frame gives focus to a painting hanging on a wall.

High contrast

High contrast also helps to bring focus to important areas by accentuating shapes and movement. Since early human development, people have used contrast to interpret visual information.

Leading lines

Leading lines direct focus on an area of importance by arranging the camera position and elements on the screen to work as arrows for the viewer.

Rule of thirds

Rules of thirds is another common compositional idea, which simplifies the golden ratio principle by dividing the width and height of the camera frame into thirds with vertical and horizontal lines. Key information is placed within the areas of the screen where those lines intersect.

Practice

Task 3: Identify composition techniques used in three shots

Knowing about the composition techniques used by filmmakers can help your process of creating visually interesting storyboards. Can you identify the key composition techniques used in the three shots below?

What tools or resources do you need for this task?

- Your saved Film Techniques worksheet.

- Swipe through these three images to help you complete this learning task:

What steps should you take to complete this task?

15-20 minutes

Set aside up to 20 minutes to complete steps 1-4 below. Remember to save your work as you go when using Word.

- Examine each of the three shots above.

- Identify the key composition techniques used in each shot.

- Record these key composition techniques in the corresponding worksheet section.

- Make any required updates to your Film Techniques worksheet and save to your device.

What should you do after completing this task?

- Reflect on how different composition techniques guide the viewer's attention and contribute to the storytelling. How might using different composition techniques enhance your storyboarding?

- Share your Film Techniques worksheet to Forum:

- Select your forum thread in Forum: Visual Storytelling - remember to create your thread if you have not already done so.

- Select Reply to your first Forum post.

- Enter the words ‘Task 3: Film Techniques’ in your reply.

- Select the Post your response button, then select Edit in your new reply when it shows up.

- Upload your worksheet using the Attachment field.

- Select Save changes to share your coursework to your forum thread.

- Get feedback on this and the previous two learning tasks at the next Live Session – check the Live Session calendar for dates and times.

Take a breather and then move to the next subtopic, Film Influences and Film Study, where you can identify your film influences and gear up to practice a key assessment task – writing a film study!

Embark on a journey through the world of film - from identifying your film influences and your favourite sequence and shots to learning the steps involved in writing a film study, uncover the depths of the cinematic experience.

Film influences

Important

Use the Film Influences worksheet

In this section, you’ll practise three learning tasks:

- Create a list of your ten favourite films.

- Create a reference board of key shots from two favourite sequences.

- Explain aspects of key shots from your reference boards.

Note: You only need to post to Forum: Visual Storytelling once by using the same worksheet for all three tasks. Just follow these three steps:

- Download this Film Influences worksheet.

- As you work through each learning task, record your findings in the corresponding section of the worksheet – don’t forget to save to your device as you go!

- After completing all learning tasks, upload your completed worksheet to Forum: Visual Storytelling for feedback.

You’ll get a reminder to use the worksheet in each learning task within the Film Influences section.

Watching and discussing films and film sequences – and the ones that influence you as an individual – is a great way to develop your understanding of visual storytelling and filmmaking techniques.

What are your favourite films?

Practice

Task 4: Create a list of your ten favourite films

Do you feel a personal connection to films you’ve watched and enjoyed? Knowing your own preferences and tastes helps you approach visual storytelling with a more personal and critical perspective.

What tools or resources do you need for this task?

- Make sure you have access to the Film Influences worksheet.

What steps should you take to complete this task?

15-20 minutes

Set aside up to 20 minutes to complete steps 1-3 below. Remember to save your work as you go when using Word.

- Download the Film Influences worksheet.

- List in the corresponding worksheet section your ten favourite films (animated or live action).

- Make any required updates to your Film Influences worksheet and save to your device.

What should you do after completing this task?

Great work on identifying your top ten favourite films. Now it’s time to zoom in on specific film sequences from your list.

What are your favourite sequences?

Reflection

From rebels to raiders

Think again about the ten films you listed in the previous learning task.

In those films, are there any specific sequences or shots that you really like or that influence you more than others?

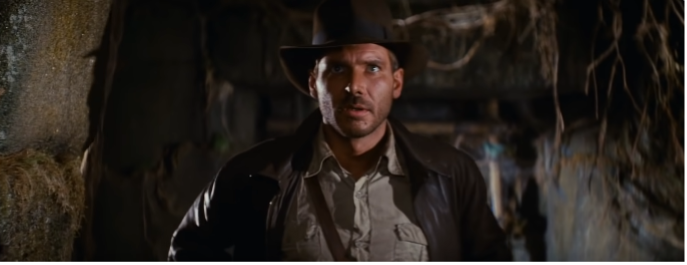

An animation tutor at Yoobee shared two of their favourite sequences, from The Empire Strikes Back and Raiders of the Lost Ark (both films by Lucasfilm Ltd.) and provided reasons why the sequences stood out.

Swipe through both sequences (eight shots each) and read the tutor’s comments.

I like the Hoth battle sequence in The Empire Strikes Back with the AT-AT walkers and the thrilling flight of the snow speeders and the climax where Luke manages to destroy one of the walkers with his lightsabre...

…or Raiders of the Lost Ark in the opening sequence when you are introduced to the character while he is recovering the Idol from inside the temple culminating with the boulder chase.

Practice

Task 5: Create a reference board of key shots from two favourite sequences

Identifying and isolating key shots within film sequences can help you focus on visual storytelling and film techniques that make those shots memorable. Starting with sequences, which stand out to you as a viewer?

What tools or resources do you need for this task?

- Your saved Film Influences worksheet.

What steps should you take to complete this task?

30 minutes

Set aside up to 30 minutes to complete steps 1-4 below. Remember to save your work as you go when using Word.

- Open your Films Influences worksheet.

- Select a favourite sequence from each of the two films in your top ten list.

- Create a reference board of key shots using the corresponding worksheet section:

- Your reference board should have approximately 6-8 shots per sequence (i.e. 12-16 shots across two sequences in total).

- Keep the shots in chronological order.

- Make any required updates to your Film Influences worksheet and save to your device.

What should you do after completing this task?

Now that you've selected your two sequences and created a reference board, it’s time to delve deeper into the individual key shots that impact you as a viewer.

What are your favourite shots?

Choose one of your sequence reference boards and review the shots you have included. Ask yourself three questions:

- What do you really like about each shot?

- What do you think the director was trying to tell you about that moment in the story?

- Is there any detail in each shot that you think stands out as important for the wider story?

Select + to:

- Look at specific shots from the Raiders of the Lost Ark sequence.

- Read the Yoobee animation tutor’s review of why these shots are so appealing.

“I particularly like the sense of mystery and suspense which is achieved during the entry to the temple by the pacing and lighting of the shots in the sequence. There’s a feeling of building tension and anticipation, which contrasts well with the frantic pace of the climax at the end of the sequence.”

“The reveal of the Idol on the plinth is very effective due to the lighting in the shot. The background is darker, with bright golden light bathing the idol, which draws your attention to the centre of the frame.

“The composition of the shot itself is ritualistic with the placement of the Idol at the centre of the image, which mirrors many examples of religious iconography.”

“The pacing of the sequence has some great moments where the main character pauses to consider how best to achieve his goal of getting the Idol.

“My favourite moment/shot is the moment where Indy has reached the Idol and is considering the best method to take it and not set off any traps, which ultimately fails! The lighting in this shot is particularly effective in framing the Idol and the main character from the darker surroundings of the temple.”

“And finally, the sequence is capped off with the fast-paced and intense rush to get out of the temple alive after setting off the booby traps!”

Practice

Task 6: Explain aspects of key shots from your reference boards

Have you ever tried to explain to someone else why key shots in a film sequence appeal to you as a viewer or why they're so effective? It's a skill that will come in handy when you practice writing a film study, which is the focus of the next section in this Film Influences and Film Study topic.

What tools or resources do you need for this task?

- Your saved Film Influences worksheet.

What steps should you take to complete this task?

1 Hour

Set aside one hour to complete steps 1-5 below. Remember to save your work as you go when using Word.

- Revisit the What are your favourite shots? section above.

- Open your Films Influences worksheet.

- List a key aspect (i.e. a film technique or a visual element) that stands out to you in each shot on your reference board.

- Write 1-2 sentences for each aspect you have listed, explaining why you think it makes the shot effective in telling the story.

- Make any required updates to your Film Influences worksheet and save to your device.

What should you do after completing this task?

- Reflect on how identifying and explaining the aspects of key shots has enhanced your understanding of visual storytelling. How has it improved your ability to break down film sequences and articulate your observations?

- Share your Film Influences worksheet to Forum:

- Select your forum thread in Forum: Visual Storytelling.

- Select Reply to your first Forum post.

- Enter the words ‘Task 6: Film Influences’ in your reply.

- Select the Post your response button, then select Edit in your new reply when it shows up.

- Upload your worksheet using the Attachment field.

- Select Save changes to share your coursework to your forum thread.

- Get feedback on this and the previous two learning tasks at the next Live Session – check the Live Session calendar for dates and times.

In this Film Influences section, you’ve identified your own film preferences and explained how key shots in your favourite film sequences impact you as a viewer. Get ready to dissect film techniques and visual elements even more in the next step of your visual storytelling journey - Film Study.

Film study

Writing a short film study is a great way for you to:

- Learn techniques related to shot types, camera movements, transitions, and composition.

- Build your knowledge of visual storytelling as an animator.

- Help improve your storyboarding and the way you develop your animated sequences.

Important

Gearing up for your assessment tasks

Your first task assessment for this module involves you writing and submitting a film study for a film sequence that has had an influence on you.

In this section, you’ll find seven steps designed to guide you through the process of writing a compelling film study. You'll also encounter five learning tasks to help you practise these steps, using as a case study the animated film Brave.

As you work through each step, remember that writing a film study goes beyond merely dissecting scenes—it's your chance to demonstrate your understanding of visual storytelling techniques. From watching the film to checking your writing, each step plays a vital role in writing an insightful film study.

What is a film study?

In a nutshell, a film study explains:

- the story being told in the film sequence

- how well a film sequence works, and

- why the film sequence works (or doesn’t).

The various elements a film study focuses on include the use of film techniques – such as shot types and camera movements - and the historical and cultural context that the story is set in.

How do you write a film study?

Writing a film study consists of seven steps:

Step 1: Watch a film sequence and list your observations

The first step in writing a film study involves watching a film sequence and listing the:

- visual elements that describe the settings

- film techniques used to tell the story.

The information you list should be specific and include information, details, and examples about the settings and shot types.

It means you need to actively take notice. A good way is to ask yourself the following questions when you watch the film sequence:

- What do you notice about the cultural setting – the world and its characters?

- What about the historical setting – the time period, technologies, and living conditions?

- What do you notice about the film techniques (i.e. types of shots, camera movements, transitions, composition)?

- What film techniques are used?

- Why have these film techniques been used?

Practice

Task 7: List your observations from the opening sequence of Brave

Practice the initial step in writing a film study by carefully observing and documenting the visual elements and film techniques used in the opening sequence of Brave.

This learning task will help you understand how these elements contribute to storytelling and set the stage for your Brave film study.

What tools or resources do you need for this task?

Make sure you have access to:

- the Brave opening sequence (3:18m): Brave Opening Scene (youtube.com)

- an application like Microsoft Word or a similar note-taking app to document your observations.

What steps should you take to complete this task?

15-20 minutes

Set aside 20 minutes to complete steps 1-4 below. Remember to save your work as you go when using your note-taking app.

- Watch the opening sequence of Brave and actively take notice of the visual and cinematic elements presented.

- List its visual elements:

- Observe the cultural setting:

- What do you notice about the cultural setting?

- How do the characters interact with their environment?

- Document specific details such as costumes, architecture, and societal norms.

- Consider the historical setting:

- What do you notice about the historical setting?

- How does the time period influence the story?

- Record examples of technologies, tools, and living conditions shown in the sequence.

- Observe the cultural setting:

- Identify film techniques:

- Pay attention to the types of shots and camera movements:

- What film techniques are used?

- How do these techniques help tell the story?

- Note specific examples of shot types (e.g., close-ups, medium shots, wide shots) and camera movements (e.g., pans, tilts, zooms) and consider their purpose in the narrative.

- Observe the composition and transitions:

- What do you notice about the composition and framing of shots?

- What types of transitions are used?

- List examples of composition techniques (e.g., rule of thirds, leading lines) and transitions (e.g., cuts, fades, dissolves).

- Pay attention to the types of shots and camera movements:

- Organise and save your list of observations into clear categories (e.g., cultural setting, historical setting, shot types, camera movements, composition, transitions).

What should you do after completing this task?

Think about how the visual elements and film techniques in the opening sequence of Brave contribute to your understanding of the sequence’s setting and characters. In what ways do your observed film techniques enhance or detract from the narrative being told?

Use your observations as a foundation for the next steps in drafting your film study of Brave, the next of which is writing the introduction.

Step 2: Prepare an introduction

Using the observation lists you created in Step 1, you’re ready to write an introduction for your film study!

You need to introduce the film the sequence is from and what the sequence is about:

- Start by listing key details about the film sequence, including:

- film title

- production company

- year of release

- director

- a brief story synopsis (e.g. world, setting, characters) in your own words.

- Then, connect these key details and, with a bit of tweaking, write a basic introduction of two or three sentences.

Practice

Task 8: Write an introduction for your Brave film study

Use your observation lists created in the previous learning task to write an engaging introduction for your film study of Brave.

By summarising key details about the film sequence and weaving them together, you’ll introduce the film's context, storyline, and visual elements to hook your reader.

What tools or resources do you need for this task?

Make sure you have access to:

- your list of observations of the opening sequence of Brave.

- an application like Microsoft Word or a similar word-processing app to draft your film study.

What steps should you take to complete this task?

30 minutes

Set aside 30 minutes to complete steps 1-4 below. Remember to save your work as you go when using your word-processing app.

- List key details about the film sequence, including:

- Film title

- Production company

- Year of release

- Director

- Write a concise story synopsis (a brief outline) in your own words using your list of observations, covering the world, setting, and characters depicted in the sequence.

- Use the key details and your short synopsis to write a basic introduction of 2-3 sentences that:

- Introduces the film title, production company, year of release, and director to establish context.

- Provides a concise overview of the sequence’s storyline, offering insight into the world, setting, and characters portrayed in the sequence.

- Save your draft: Choose a clear and descriptive filename for your document, such as ‘Brave_Film_Study’.

What should you do after completing this task?

How successfully does your introduction encapsulate the essence of the Brave film sequence and engage the reader’s curiosity to explore your film study further? What adjustments could enhance the clarity and appeal of your introduction?

When you’re ready, use your introduction as a springboard for the next step of writing paragraphs on film techniques and visual elements for your Brave film study.

Step 3: Prepare several paragraphs about the storytelling

Again, using your notes from Step 1, you’re ready to write some paragraphs describing the storytelling.

It’s about expanding your observations from your original lists and adding examples and details.

- Start by writing sentences that build on items in your observation lists.

- String these new sentences together into short paragraphs describing the film sequence’s:

- film techniques (i.e. types of shots, camera movements, transitions, composition)

- visual elements that describe historical and cultural settings.

Practice

Task 9: Write paragraphs on film techniques and visual elements for your Brave film study

Expand upon your observations from the previous two learning tasks and delve deeper into your breakdown of film techniques and visual elements in the Brave film sequence.

By crafting several descriptive paragraphs, you’ll provide detailed insights into how these techniques and elements contribute to the storytelling and overall impact of the sequence.

What tools or resources do you need for this task?

Make sure you have access to:

- your list of observations of the opening sequence of Brave

- your saved Brave film study draft.

What steps should you take to complete this task?

2 Hours

Set aside two hours to complete steps 1-7 below. Remember to save your work as you go when using your word-processing app.

- Revisit your list of observations of the opening sequence of Brave.

- Identify key points related to film techniques (such as types of shots, camera movements, transitions, composition) and visual elements (depicting historical and cultural settings) that you noted during the film sequence.

- Based on the items in your observation lists, write descriptive sentences that expand upon each point.

- Provide examples and specific details to illustrate how each film technique or visual element enhances the storytelling in the Brave sequence.

- String together the new sentences you've written into short paragraphs.

- Organise these paragraphs into two sections:

- Paragraphs describing the film sequence's film techniques.

- Paragraphs describing the visual elements that depict historical and cultural settings.

- Save your film study draft.

What should you do after completing this task?

How well do your paragraphs convey the significance of the film techniques and visual elements in enhancing the storytelling? What additional details or examples could strengthen your film study?

It's time to expand your understanding further by exploring additional sources such as articles, books, or interviews related to the film sequence. By including insights from these sources in your film study, you'll deepen your comprehension of visual storytelling, sharpening your ability to use visual and film elements within the context of animation.

Step 4: Use other sources of information

You’ve already done the hardest part of your film study in the previous three learning tasks. Now, starting with what you already know, look for other sources for information to expand on your film study.

Using other sources of information helps you unpack a film sequence and gives weight to ideas you've formed. These other sources can also challenge your ideas.

- Watch or read sources such as ‘the making of…’ documentaries, articles about the film, or interviews with its director.

- Take notes of any important quotes that seem relevant to the observations you have already made in your film study. These quotes could be the director's comments about shot choices, composition, camera movement or other storytelling tools.

- You need to cite these quotes later on, so note down where the quotes have come from.

Case Study

Sourcing directorial insights: Mark Andrews and Brave

You’ve already identified that Brave was made by Pixar and directed by Mark Andrews. Now, imagine you'd like to find sources of information about camera techniques that enhance the storytelling in Brave.

Explore direct sources

You could search to find out if Andrews explains his approach to filmmaking in sources such as interviews, 'the making of...' documentaries, featurettes, or media articles.

Watch this brief excerpt (5.20m, starting from 1.24m) of Andrews's lecture to CalArts (California Institute of the Arts) students:

Andrews emphasises how important it is:

to tell the story as economically as possible, letting an image sell itself and give the information that makes sense.

His words, quoted here, reflect observations you may already have made when watching the opening film sequence from Brave. In just the first few shots, the economy of storytelling is very evident, and viewers quickly learn about the world, characters, and historical and cultural settings. All of that is packed into just the two opening shots.

Explore other directions for sources

You could also explore other directions when looking for sources to inform your film study.

Search for ‘Mark Andrews filmography’ online. You'll discover he's worked as a storyboard artist on films like Pixar's The Incredibles, directed by Brad Bird.

Several excerpts are available online in featurettes about making The Incredibles, where Andrews discusses his approach to storyboarding – you can see some of those same ideas in his work on Brave as director.

You could also look to Bird to explore how his directorial choices are similar to (and may have influenced) Andrews’s directorial choices in Brave.

Explore possible connections with sources

Feel free to explore possible connections by seeking examples (i.e. evidence) to support or counter different thoughts and ideas.

The economy that Andrews referred to in the YouTube source above is perhaps most obvious in the handling of characters.

The main character in Brave, Merida, has physical features that reflect her personality, making it almost instant for an audience to understand or identify with the character. She has a:

Brenda Chapman, Co-director and Co-writer of Brave… mass of curly, unbridled, wild hair…. It just had to be red, because she's passionate and fierce and independent, so that as soon as she walks out on screen, you know exactly what her story is, without the filmmakers needing to go into any exposition to see what her character is like.

Economical thinking is equally evident in the environments in Brave. Consider this quote:

Steve Pilcher, Production Designer for BraveMovie making is a visual storytelling medium, and everything that we do supports the story. The design of the backgrounds, the design of the castle, the characters, what we’re trying to say about the land, it’s all in the design.

By exploring the methods of directors such as Mark Andrews, you gain deeper insights into storytelling and film techniques that shape animated experiences like Brave. Exploring various sources for directorial insights will enrich your film study and provide valuable perspectives.

Practice

Task 10: Source quotes for your Brave film study

Deepen your understanding of visual storytelling elements in the Brave film sequence by sourcing quotes from relevant materials such as documentaries, articles about the film, or interviews with its director. By incorporating other sources into your film study, you'll give weight to - and even challenge - your ideas around visual storytelling and provide valuable insights from the creators and themselves.

What tools or resources do you need for this task?

Make sure you have access to:

- the Brave 2012 Behind The Scenes documentary (1:13:46h):

- your saved Brave film study draft.

What steps should you take to complete this task?

2 Hours

Set aside two hours to complete steps 1-6 below. Remember to save your work as you go when using your word-processing app.

- Watch the Brave 2012 Behind The Scenes documentary to gain insights into the filmmaking process and the creative decisions behind the Brave film sequence.

- Note any important comments or other significant insights that align with your previous observations in your film study while watching the documentary.

- Note each quote’s source (i.e., timestamp in the documentary) to ensure proper citation later. This step is essential for citing your sources accurately in your film study and providing proper attribution to the creators.

- Extend your research by watching or reading other relevant sources such as documentaries, articles about the film, or interviews with its director. Repeat Steps 2-3 for each new source.

- Integrate the quotes into your film study by weaving them into your paragraphs to support your interpretations of visual elements and film techniques used in the Brave opening sequence.

- Save your film study draft.

What should you do after completing this task?

How have your sourced quotes enhanced your breakdown of visual storytelling elements in Brave? What new perspectives or insights have you gained from these quotes?

At this point, your film study is really coming together! Take a moment to acknowledge the excellent progress you've made so far. Keep up the great work, and continue refining your words. Next, find out how to:

- Expand your paragraphs and check your progress.

- Use APA Style referencing.

- Do a final check.

- Fine-tune and complete your Brave film study.

Step 5: Expand your paragraphs and check your progress

By now, your film study is taking shape nicely!

Extend your paragraphs

Back in Step 3, you described the film techniques and visual elements that make up the film sequence. You now need to explain:

- which film techniques and visual elements work well, and

- why they work well.

To do this, write two extra sentences for each paragraph explaining what worked well and why.

For example, with your film technique paragraphs (e.g. types of shots):

- Identify which shots are the most effective and would impact an audience most.

- Explain why this is the case.

Check your progress

Once you expand your paragraphs, it’s time to check your film study to make sure you’re on track.

Checklist 1

Use this Checklist 1 to guide you through the criteria to make sure you're on track at this point in your film study.

| # | Criteria | Completed (Yes/No) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduce key details of the film sequence including: | |

| 1.1 | - Film title | |

| 1.2 | - Production company | |

| 1.3 | - Year of release | |

| 1.4 | - Director | |

| 1.5 | - A very brief story synopsis (e.g. world, setting, characters) | |

| 2 | Indicates the specific part of the film being reviewed and its approximate timecode | |

| 3 | Identifies specific film techniques observed in the film sequence and discusses effectiveness and impact | |

| 4 | Identifies specific visual elements (that describe historical and cultural settings) observed in the film sequence and discusses effectiveness and impact | |

| 5 | Uses specific examples from other sources to support comments, perspectives, and conclusions | |

| 6 | Meets word count – aim for 500-1000 words, equivalent to one to two A4 pages (11-point type) |

Step 6: Use APA Style referencing

Remember back in Step 4 how you used other sources of information to find important quotes?

It’s now time to reference these sources in your film study using a referencing style called APA Style.

Tip

Reference with precision – Academic Writing Essentials

APA Style is widely used in academic writing and research to acknowledge the ownership of sources of information and ideas used in a paper or article – like a film study.

APA Style provides you with guidelines to format:

- citations within your text

- a reference list at the end of your film study

You’ll find more information on using APA Style when referencing your sources in the Academic Writing Essentials subtopic. Just follow these breadcrumbs:

4. Foundations > 4.2 Visual Storytelling > 4.2.4 Academic Writing Essentials > Referencing

Step 7: Do a final check

Now for the final step! Spend time thoroughly checking your work for its:

- writing style

- clarity

- use of paragraphs

- avoidance of first-person writing

- grammar

- spelling.

Tip

Polish your writing!

Looking to improve your writing for your film study assessment task?

Check out the following Academic Writing Tips subtopic for helpful strategies. From crafting clear paragraphs to avoiding first-person writing, you'll find helpful tips to elevate your writing.

4. Foundations > 4.2 Visual Storytelling > 4.2.4 Academic Writing Essentials > Academic Writing Tips

You can also seek feedback on your work (and check you’ve used APA referencing properly) with your facilitator.

Checklist 2

Use this final Checklist 2 to guide you through the final check criteria:

| # | Criteria | Completed (Yes/No) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduce key details of the film sequence including: | |

| 1.1 | - Film title | |

| 1.2 | - Production company | |

| 1.3 | - Year of release | |

| 1.4 | - Director | |

| 1.5 | - A very brief story synopsis (e.g. world, setting, characters) | |

| 2 | Indicates the specific part of the film being reviewed and its approximate timecode | |

| 3 | Outlines which materials you’ve sourced during your review, e.g. filmscripts, storyboards, ’the making of…’ documentaries, interviews, articles. | |

| 4 | Identifies specific film techniques observed in the film sequence and discusses effectiveness and impact | |

| 5 | Identifies specific visual elements (that describe historical and cultural settings) observed in the film sequence and discusses effectiveness and impact | |

| 6 | Uses specific examples from other sources to support comments, perspectives, and conclusions | |

| 7 | Includes citations and uses APA referencing style. | |

| 8 | Meets word count – aim for 500-1000 words, equivalent to one to two A4 pages (11-point type) |

Practice

Task 11: Fine-tune and complete your Brave film study

It's time to finalise and polish your Brave film study! Expanding your paragraphs, checking your progress, and following APA style guidelines will help you complete a well-structured, comprehensive, and insightful film study.

This learning task also includes an opportunity for you to receive valuable feedback on your film study, helping you refine your work and craft an even better film study as part of this module's first assessment task.

What tools or resources do you need for this task?

- Make sure you have access to your Brave film study draft.

What steps should you take to complete this task?

2 Hours

Set aside two hours to complete steps 1-6 below. Remember to save your work as you go when using your word-processing app.

- Revisit the Film Study section to reinforce what you know if you need to.

- Expand your paragraph by adding depth where needed, ensuring each paragraph supports your breakdown of the film techniques and visual elements in the Brave opening sequence.

- Check your progress to make sure you’re on track.

- Refer to the Check Your Progress checklist above.

- Re-read your film study to ensure it flows logically and coherently.

- Make sure each paragraph transitions smoothly to the next.

- Meet the word count. Aim for a word count of 500-1000 words, equivalent to one to two pages A4 pages in 11-point type. Adjust your content to be concise yet thorough, ensuring you stay within this limit.

- Use APA Style to acknowledge your sources:

- Review all quotes and references you've included in your film study.

- Format each citation according to APA Style guidelines, ensuring proper attribution to sources.

- Tip: Visit the Academic Writing Essentials subtopic to learn how to use APA Style.

- Complete a final check:

- Clarity: Make sure your ideas are clearly expressed and easy to follow.

- Use of paragraphs: Ensure each paragraph has a clear main idea and supporting details.

- Grammar and spelling: Proofread your film study for grammatical or spelling errors.

- Save your final draft using a clear and descriptive filename, such as ‘Brave_Film_Study_Final’.

- Post your completed film study to the forum for feedback (see below).

What should you do after completing this task?

- Reflect on the evolution of your film study from its initial stages to completion. What challenges did you face in breaking down the visual storytelling elements of the Brave opening sequence, and how has your understanding of film techniques used in animated films deepened?

- Share your Brave film study to Forum:

- Select your forum thread in Forum: Visual Storytelling.

- Select Reply to your first Forum post.

- Enter the words ‘Task 11: Film Study’ in your reply.

- Select the Post your response button, then select Edit in your new reply when it shows up.

- Upload your photo(s) or files using the Attachment field.

- Select Save changes to share your coursework to your forum thread.

- Get feedback on this and other learning tasks at the next Live Session – check the Live Session calendar for dates and times.

It’s time for a well-deserved break away from your device! When you come back, look out for the next subtopic, Academic Writing Essentials, if you need help with referencing or citing your sources.

Alternatively, go straight to the next subtopic, Story Concept Development to discover the initial step of animating your final sequence!

Use this Academic Writing Essentials subtopic to discover how to enhance your film study through proper referencing. Learn to accurately cite your sources, ensuring your work is credible and traceable, setting the stage for a well-supported and comprehensive film study.

Important

Connecting Academic Writing Essentials with your Film Study

Knowing the essentials of academic writing is critical when writing a film study, particularly for Step 6: Prepare References and Citations. That step involves providing specific references for your sources in the proper format to enhance the credibility of your work.

How this subtopic helps you:

- Proper referencing: Learn the correct format for listing sources in your reference list, ensuring your film study clearly references the specific part of the film you are reviewing and helping you avoid plagiarism.

- Citation styles: Familiarise yourself with the APA Style commonly used at Yoobee. This knowledge is important for formatting your in-text citations accurately.

- Paraphrasing and quoting: Effectively integrate ideas and statements from your sources into your film study.

By leveraging the skills from this subtopic, you'll be well-prepared to create references and citations, strengthening your film study and acknowledging the wider intellectual and filmmaking communities.

Referencing

Citing (i.e. referring to) the sources that helped you produce your written work (such as your film study) means that you can:

- Acknowledge the ownership of sources you've used to write your film study.

- Provide information to the reader to help them identify and retrieve the sources if they want to find out more.

To help you do this, you need to use referencing.

Various referencing styles are used depending on the needs of a particular discipline or academic area. Yoobee College of Creative Innovation uses American Psychological Association (APA) Style.

APA Style includes two key referencing elements you need to use in your film study:

| Referencing element | Description |

|---|---|

| In-text citation | Very brief information about a source is inserted into the body of your text (hence ‘in-text’), allowing readers to locate the full source information in your reference list. |

| Reference list | A comprehensive list at the end of your film study, detailing full information of all sources you’ve cited in your text. |

How do you create in-text citations?

Use APA Style’s author-date system for in-text citations, which combines up to three basic components:

- last name (e.g. Miyazaki) of the source’s creator

- year of publication (e.g. 1988) of the source

- timestamp (e.g. 12:35) when citing from audio-visual sources (e.g. a filmed interview).

You then insert the citation (Miyazaki, 1988) into your text:

This film (Miyazaki, 1988, 12:35) portrays the director’s masterful animation, blending whimsical character design with lush, evocative backgrounds.

Two different types of in-text citations

You can choose between two different types of in-text citations:

| In-text citation type | Description and example |

|---|---|

| Parenthetical citation |

Used when the focus is on the information or idea rather than the creator. Useful for integrating the source without disrupting the text’s flow: This film (Miyazaki, 1988, 12:35) portrays the director’s masterful animation, blending whimsical character design with lush, evocative backgrounds. |

| Narrative citation |

Used when the creator’s name is integral to the sentence, highlighting their contribution or perspective. Useful for emphasising the authority or significance of the source. Miyazaki (1988: 12:35) portrays his masterful animation style, blending whimsical character design with lush, evocative backgrounds. |

The formatting for these two types of in-text citations applies to a source with either one or more than one author:

| Number of authors | Parenthetical citation | Narrative citation |

|---|---|---|

| One author | (Miyazaki, 1988, 12:35) | Miyazaki (1988, 12:35) |

| Two authors | (Miyazaki & Niwa, 2010, 8:34) | Miyazaki and Niwa (2010, 8:34) |

| Three or more authors | (Miyazaki et al., 2013) | Miyazaki et al. (2013) |

| Organisation | (Kinema Junpo Movie Database, 2020) | Kinema Junpo Movie Database (2020) |

How do you create a reference list?

At the end of your film study, list all the works you've referred to in your writing under a heading called 'References'.

References are always longer than in-text citations but have all the information needed for a reader to locate the source. Its formatting changes depending on whether your source is visual, written or verbal, online or printed.

Follow these steps to ensure your reference list is properly formatted:

- Heading: Start with the heading ‘References’ centred at the top of the page.

- Format for films:

- Begin with the last name and first initial of the author/creator: (Miyazaki, H.)

- In parentheses, specify the creative role in italics: (Director)

- Include the year of release in parentheses: (1988)

- Write the film title in italics, followed by the type of film in square brackets: [Animated feature]

- Conclude with the country of origin and the distributor: Studio Ghibli

Example of reference list item for a film source

For the in-text citation (Miyazaki, 1988), you would write the following in your reference list:

- Last name and first initial of the author/creator

- Creative role (for films)

- Year of release

- Film title and type of film

- Country of origin and distributor

Tip

Stay Organised, Research Efficiently, Cite Correctly

Save your sources’ links as you research - list all the references and in-text citations as you draft your film study to avoid none are missing from your reference list.

It’s best to use an APA referencing resource to get the structure right. You’re not expected to remember the exact format of different types of reference formatting, but you can use a reference ‘generator’ resource to support you.

For more information on APA Style, visit How to Cite in APA Style. You can also use this site’s APA Citation Generator to help you when creating your reference list.

Quoting and paraphrasing

Referencing often involves directly quoting or paraphrasing your sources.

Quoting and paraphrasing are two essential techniques for integrating evidence into and supporting your film study, while ensuring you give credit to the original authors.

Using and citing quotations

Quotations must be identical to the source text. Enclosing the words in quotation marks (" ") signals that the words are quoted directly from another source.

Quotations require in-text citations.

Example of a citation for a quotation

Original source:

Zaboomafoo, a fictional lemur who teaches children about wildlife, starred in his own TV show for multiple seasons on PBS. His huggability endeared him to thousands of children, increasing his ability to spread a love of nature and science to the masses. - Andrew Soria, from Childhood Nostalgia, 2014.

Quotation with in-text citation:

Zaboomafoo “spread a love of nature and science to the masses” (Soria, 2014, p. 4).

Note the use of quotation marks!

Paraphrasing

Use paraphrasing when you convey the meaning of information from the source material, but in your own words i.e. a paraphrase, and not as a direct quote.

A paraphrase also requires an in-text citation, as it is still adapted from another source.

You may find practising paraphrasing in your writing useful, as it allows you to summarise and present information in your own words.

Example of a citation for a paraphrased statement

Original source:

Zaboomafoo, a fictional lemur who teaches children about wildlife, starred in his own TV show for multiple seasons on PBS. His huggability endeared him to thousands of children, increasing his ability to spread a love of nature and science to the masses. - Andrew Soria, from Childhood Nostalgia, 2014.

Paraphrased statement with in-text citation:

Zaboomafoo the lemur is a furry, lovable, and kind PBS character that instilled a love of wildlife and science in young TV audiences (Soria, 2014).

Note the absence of quotation marks – it’s your paraphrase, not a direct quote. Remember, however, to still cite the paraphrase with an in-text citation (in the example above, a parenthetical citation).

Writing tips

A well-referenced paper is crucial, but writing with clarity and coherence is equally important. This section provides essential tips for organising your ideas effectively and ensuring your film study is well-structured and polished.

Write with style and clarity

Many students make the mistake of thinking that the content of their paper is all that matters. Although the content is important, it will mean little if the reader can't understand what you are trying to say.

Create clear paragraphs

Creating clear paragraphs is essential. Paragraphs come in so many sizes and patterns that no formula can cover them all. The two basic principles to follow are:

- A paragraph is a means of developing and framing an idea or impression. You should address only one major idea per paragraph.

- The divisions between paragraphs are not random but indicate a shift in focus. In other words, you must carefully organise the order of your paragraphs so that they are logically positioned throughout your paper. Transitions will help you with this by smoothly guiding the reader from one paragraph to the next, indicating shifts in thought or emphasis.

Tip

Using transitions

Transitions are words and phrases that help guide the reader through the logical flow of ideas and ensure smooth transitions between sentences and paragraphs. They come in various forms and serve different purposes in writing.

Here are some examples:

- Addition: Additionally, Furthermore, Moreover, In addition, Also

- Comparison: Similarly, Likewise, In the same way, Just as

- Contrast: However, Nevertheless, On the other hand, Conversely, In contrast

- Cause and Effect: Consequently, Therefore, Thus, As a result, Accordingly

- Sequence/Order: Firstly, Secondly, Lastly, Next, Finally

- Example/Illustration: For example, For instance, Specifically, To illustrate

- Conclusion: In conclusion, To sum up, Ultimately, In summary, Therefore

- Time: Meanwhile, Afterward, Subsequently

- Emphasis: Indeed, In fact, Certainly, Of course, Undoubtedly

- Result: Consequently, Accordingly, Hence, Therefore, Thus

Avoid first-person writing

The first-person point of view is considered informal and is not encouraged in academic writing. First-person can weaken the writer's credibility in research and argument, as it reads as the writer's personal opinion.

Use APA Style to reference

If you are using someone else’s idea, acknowledge it. Use APA Style to cite information from other sources, i.e. in-text citations and a reference list.

Check grammar and spelling

Make sure your film study is free from grammar and spelling mistakes. Mechanical errors are usually the main reason for lack of clarity in writing, so thoroughly proofread your film study before submitting it.

Developing your story concept sets the stage for animating your final sequence. Explore a structured process in this subtopic, accompanied by a case study of a library mystery scene, to develop a compelling narrative. Through practical insights and learning tasks, hone your skills in story concept development to excel in your assessment task of drawing a storyboard.

Important

Gearing up for your assessment tasks

An assessment task in this module involves drawing a storyboard for a sequence of 4-6 animated shots based on your story concept.

Before diving into the storyboard, developing a strong story concept is essential.

This subtopic will guide you through a structured process comprising three essential steps to develop your story concept. Using a case study of a library mystery scene, you'll gain practical insights into crafting a compelling narrative.

Additionally, you'll be able to apply these steps through two learning tasks designed to reinforce your skills in concept development.

As you work through these tasks, remember that a well-developed concept is crucial for creating a compelling storyboard. Take your time to brainstorm creatively and write a clear, concise synopsis.

Each step you complete will bring you closer to producing a storyboard that effectively conveys your final sequence story.

Developing your story concept

To develop a story concept for your storyboard, follow the three steps outlined in the diagram below:

Step 1: How do you generate ideas?

Generating ideas can be one of the hardest parts of creating an animated short sequence.

- What should you create?

- Where do you start?

Finding inspiration through film

A good place to start can be looking at the films or sequences you admire, like you did in the Film Influences section of this topic. Are there any shots or ideas from these that you could adapt and use to inspire your own short series of shots to tell a narrative?

Finding inspiration from other genres and stories

What interests you in your life outside of animation?

Do you enjoy a particular genre? Is there inspiration you can draw from a series of novels or games?

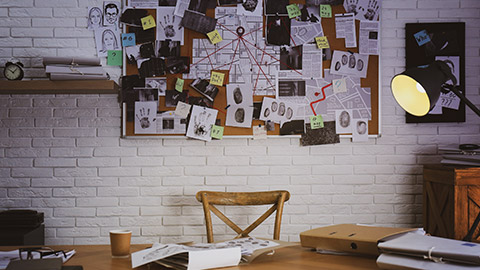

For example, do you enjoy spy or detective stories? Could you build a sequence around a private detective's office?

Brainstorming ideas with others

Brainstorming is a creative technique involving a group of people freely sharing and discussing ideas in a non-judgmental way to generate creative concepts or solutions.

Bouncing ideas with others can be an efficient way to create and develop ideas, so you could try brainstorming ideas with friends or family.

Case Study

Story concept – Generating an idea

The first part of this story concept case study describes the process of generating ideas, narrowing them down, and ultimately selecting a feasible concept (a library mystery scene) to bring to animated life.

Initial project ideas

Several ideas for possible projects were considered, including:

- Discovering the ruins of an ancient temple in the jungle.

- The messy office of a private detective during a bizarre case.

- A Victorian observatory while making an amazing discovery about the cosmos.

- A quiet underground tube station late at night as a train rattles by.

Narrowing down the ideas

Ultimately, none of these ideas were chosen for this project. The first two ideas were too broad in their scope and would require more time to complete than was available. Creating all the assets necessary to make a convincing jungle would take far too long to complete. Similarly, a messy detective's office would require more modelling and texturing than could be completed in a short timeframe, doing the idea justice.

Focusing on feasible concepts

The Victorian observatory and tube station were good ideas for interesting and achievable environments to build in the timeframe. Still, no clear idea of a narrative could be built around the setting. Too much time would likely be spent trying to build that story element of the project.

Final decision on an idea

In the end, a scenario set in the library of an old manor house was chosen. This idea provided plenty of scope to create a nice-looking environment, and the concept of an old private library sparked an idea for the essential narrative element. This narrative element would keep the audience interested in the project’s visual aspect.

Practice

Task 12: Generate three simple story ideas

Practice generating story ideas, which is the initial step in developing a story concept for your storyboard. By practising this skill, you'll gain valuable confidence in exploring various narrative possibilities and grow your storytelling abilities.

What tools or resources do you need for this task?

Make sure you have access to any app or tool that allows you to generate and record your story ideas. Choose the tools that you feel most comfortable with, or that align best with your creative process.

What steps should you take to complete this task?

1 Hour

Set aside up to one hour to complete steps 1-3 below. Remember to save your work as you go.

- Explore sources of inspiration to stimulate your creativity:

- Watch films or animated sequences that inspire you.

- Explore different genres, themes, and mediums (e.g. books, games).

- Pay attention to elements like settings, shots, and other visual storytelling techniques that resonate with you.

- Generate individual story ideas:

- Set aside dedicated time to brainstorm and generate three simple story ideas on your own.

- Use mind mapping, free writing, or visual brainstorming techniques to stimulate your imagination.

- Write down each idea as it comes to you without worrying about judgment or criticism.

- Allow yourself to explore different story concepts and let your creativity flow freely, keeping your ideas simple.

- Select your three top story ideas for upcoming story concept development.

What should you do after completing this task?

- What type of idea generation most effectively stimulated your creativity during this learning task? Which aspects of your three ideas do you find most compelling or promising?

- Share your three ideas to Forum:

- Select your forum thread in Forum: Visual Storytelling.

- Select Reply to your first Forum post.

- Enter the words ‘Task 12: Ideas’ in your reply.

- Select the Post your response button, then select Edit in your new reply when it shows up.

- Upload your photo(s) or files using the Attachment field.

- Select Save changes to share your coursework to your forum thread.

- Get feedback on this and other learning tasks at the next Live Session – check the Live Session calendar for dates and times.

Now that you've generated three promising story ideas, it's time to develop one of them further by creating a compelling narrative around it. In the next learning task, you'll practise crafting a concise synopsis that captures your concept’s storyline.

Step 2: How do you create a story around your idea?

With the basic idea chosen, the next step is to create a story or narrative element to build around your initial idea.

Sometimes, this narrative idea can spring immediately to mind as part of your inner creative process.

Case Study

Story concept – Creating a story around the chosen idea

The next phase in the story concept case study describes the main story points for the library mystery scene idea.

Main story points

The narrative framework of the project unfolds in a series of distinct story points – or story ‘beats’ – each contributing to the overall storytelling:

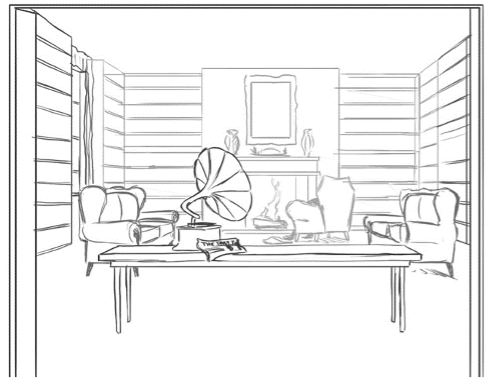

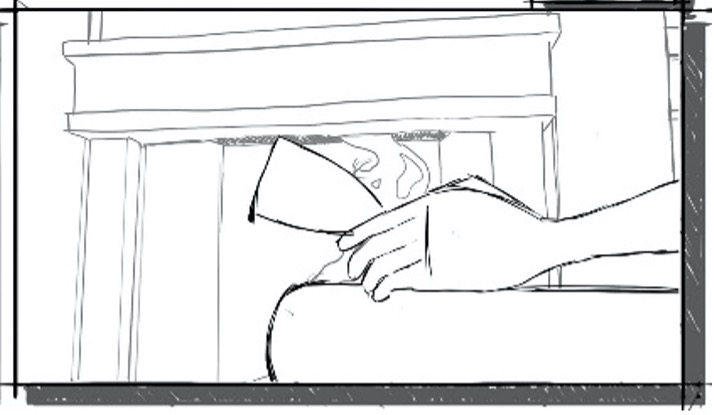

- Library entrance: The scene opens as viewers are introduced to the library setting, entering through its grand main doors, setting the stage for the unfolding story.

- Gramophone and newspaper: Moving deeper into the library, attention is drawn to a gramophone and a newspaper with a headline proclaiming "Heiress Inherits Fortune!" placed on a side table.

- Fireplace and chair: Progressing further, the focus shifts towards a large fireplace and a chair, positioned with its back to the camera, creating an air of mystery and anticipation.

- Fallen book: As viewers approach, a fallen book comes into view, lying carelessly on the floor, signalling a disruption in the tranquil library environment.

- Pool of red liquid: The fallen book reveals a pool of red liquid on the floor, juxtaposing the serenity of the library with an ominous presence. Small drips of liquid intensify the sense of unease.

- Source of the drips: Following the trail of drips, attention is drawn to a feminine hand loosely holding a nearly empty wine glass, the source of the mysterious liquid slowly dripping onto the floor.

Next step: the synopsis

These story beats serve as a foundation for writing a synopsis of the story, which in turn will guide the creation of storyboards and (eventually) the project’s animatic.

Step 3: What is a synopsis?

A synopsis is a brief paragraph that outlines and summarises the overall ‘beats’ of the story. It serves as a high-level overview without delving into exhaustive detail.

Case Study

Story concept – Writing the synopsis

The final phase in the story concept case study is writing a synopsis of the library mystery story.

Synopsis example

Think of a synopsis as a teaser or preview that describes the story, offering enough information to grasp the essence of its narrative. Read this synopsis of the library mystery story:

"We enter the library of a grand old home; the furnishings are varied, rich and comfortable, and a large painting is proudly displayed over a fireplace, which takes up most of the wall at the far end of the room. A large imposing leather chair is in front of the fireplace, with its back towards the door. An old gramophone plays softly on a side table near the door. As we approach the chair, a newspaper proudly proclaims, “Heiress inherits fortune!”. Something doesn't seem quite right; a slumped shape is lying in the chair, a book lies crumpled on the floor, and a pool of dark red liquid beside it."

Bridging concept development and storyboards

The synopsis now functions as the narrative backbone, providing a clear roadmap for the visual storytelling journey in the animated project. It serves as a direct translation of the conceptual idea into actionable scenes, guiding and shaping the creation of a storyboard.

Practice

Task 13: Write a short synopsis for one of your ideas

Develop your story concept further by crafting a short synopsis for your story idea. This task focuses on the second and third steps of concept development, where you create a cohesive story around your initial idea and write a synopsis to outline its main story beats.

What tools or resources do you need for this task?

Make sure you have access to any app or tool that allows you to generate and record your story points and synopsis. Choose the tools that you feel most comfortable with or that aligns best with your creative process.

What steps should you take to complete this task?

2 Hours

Set aside up to two hours to complete steps 1-7 below. Remember to save your work as you go.

- Choose one idea from the three you generated and selected in the previous learning task. Consider which idea resonates with you the most and has the potential to be the most engaging.

- Refine or narrow down your idea if you need to adjust it to fit the scope of your final sequence’s requirements.

- Brainstorm story points – ‘story beats’ – that could occur within the story. Consider the beginning, middle, and end.