Reading A: Leading, Managing and Developing People

Reading B: Workplace Policies and Procedures

Reading C: Recruitment and Selection

Reading D: Developing HR policies and procedures

Reading E: Example of Code of Conduct

Reading F: A Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice 1

Reading G: A Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice 2

Reading H: A Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice

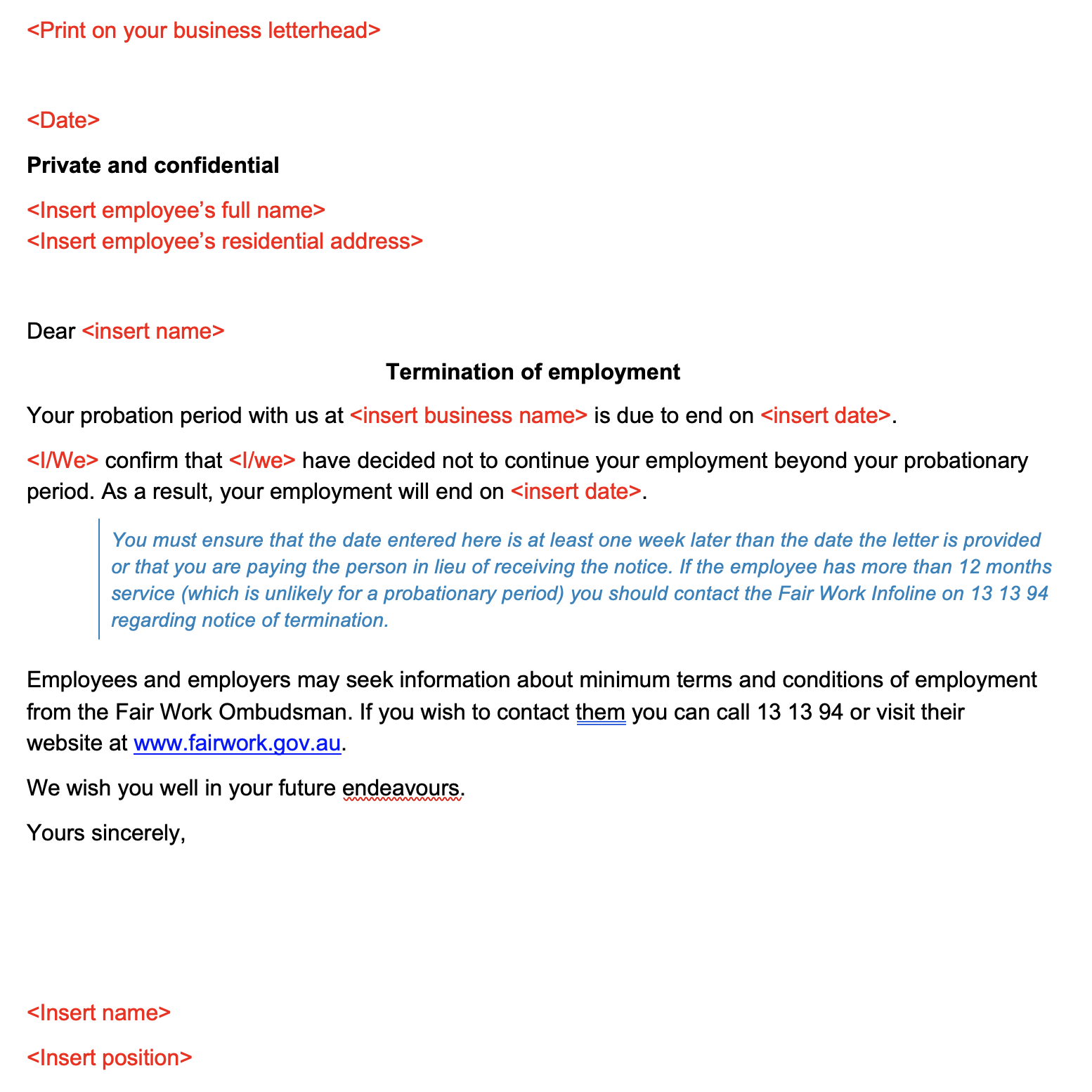

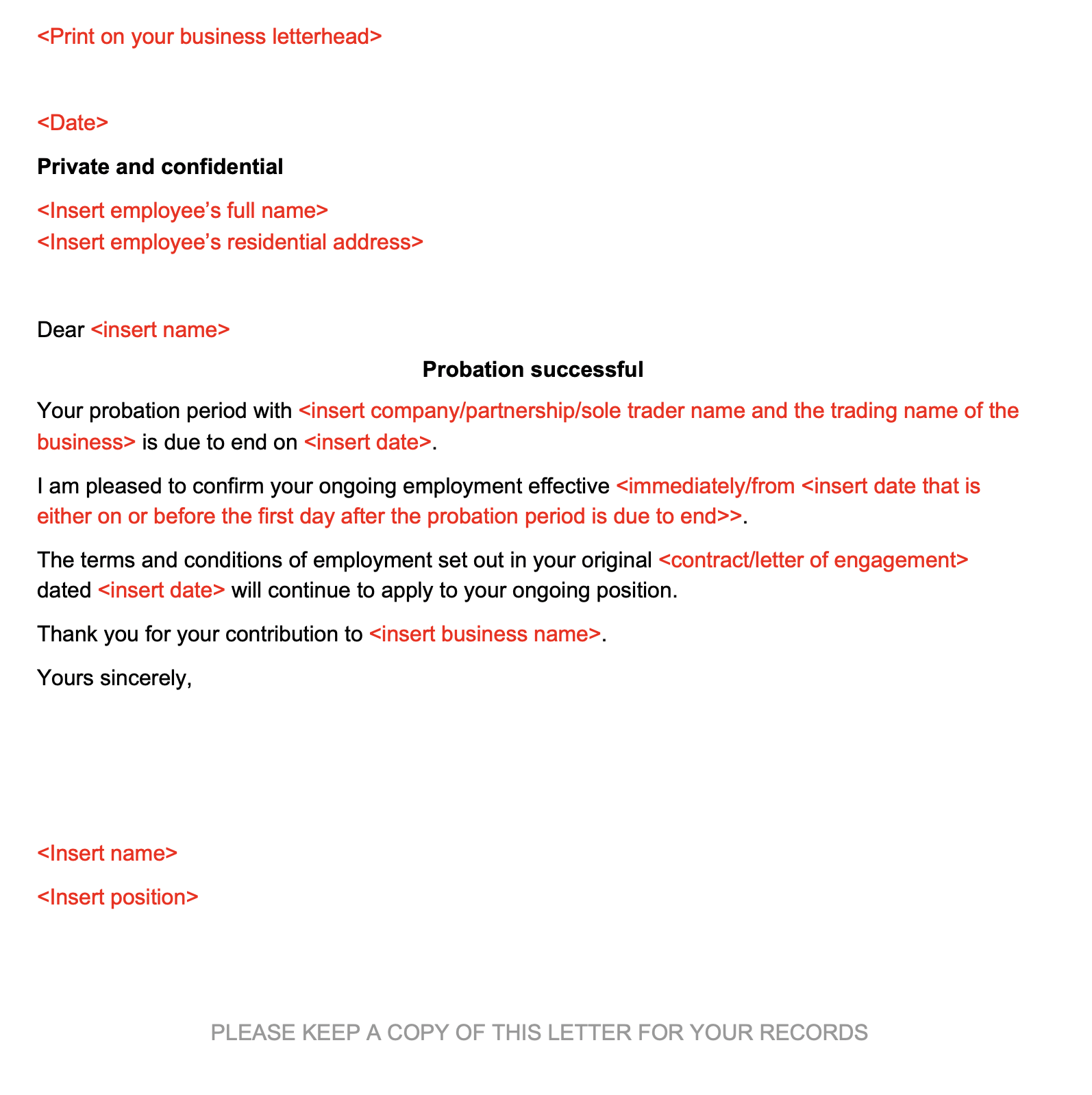

Reading I: Letters of Successful and Unsuccessful Probation Period Templates

Important note to students: The Readings contained in this BSBHRM506 Readings are a collection of extracts from various books, articles and other publications. The Readings have been replicated exactly from their original source, meaning that any errors in the original document will be transferred into this section of Readings. In addition, if a Reading originates from an American source, it will maintain its American spelling and terminology. AIPC is committed to providing you with high quality study materials and trusts that you will find these Readings beneficial and enjoyable.

French, R., & Rumbles, S. (2010). Leading, Managing and Developing People. (3rd ed.). Chartered Institute of Personal Development. pp. 169-190

Overview

In this chapter we examine the important role of recruitment and selection within the process of leading, managing and developing people. Recruitment and selection is pivotal in this regard in certain important respects. At the most basic level our focus in this book is on people management within the employment relationship. Those charged with recruiting people to posts in work organisations take a crucial ‘gatekeeper’ role; only those people selected for employment can be led, managed and developed. So in the most fundamental sense the decision to employ (or not) underpins the whole area of managing people. Issues associated with exclusion from the workplace also highlight the need for professionalism, fairness and ethical behaviour on the part of those engaged in this activity.

Recruitment and selection also has an important role to play in ensuring worker performance and positive organisational outcomes. It is often claimed that selection of workers occurs not just to replace departing employees or add to a workforce but rather aims to put in place workers who can perform at a high level and demonstrate commitment (Ballantyne, 2009). We will elaborate on the sometimes complex linkages between recruitment and selection and performance later in this chapter.

Recruitment and selection is characterised finally by potential difficulties and it is necessary to keep abreast of developments in research in the field. Research from the CIPD (2009a), for example, concluded that organisations should increasingly be inclusive in their employment offering as younger generations have grown up with the notion of flexible working, while older people have an interest in flexible working as an alternative to retirement. This is just one example of how current research can inform practice and also shows the critical importance of the social context in which recruitment and selection takes place.

Introduction

Recruitment and selection forms a core part of the central activities underlying human resource management: namely, the aquisition, development and reward of workers. It frequently forms an important part of the work of human resource managers - or designated specialists within work organisations. However, and importantly; recruitment and selection decisions are often for good reason taken by non-specialists, by the line managers. There is, therefore, an important sense in which it is the responsibility of all managers, and where human resource departments exist, it may be that HR managers play more of a supporting advisory role to those people who will supervise or in other ways work with the new employee.

As Mullins (2010, P 485) notes: ‘If the HRM function is to remain effective, there must be consistently good levels of teamwork, plus ongoing co-operation and consultation between line managers and the HR manager.’ This is most definitely the case in recruitment and selection as specialist HR managers (or even external consultants) can be an important repository of up-to-date knowledge and skills, for example on the important legal dimensions of this area.

Recruitment and selection is often presented as a planned rational activity, comprising certain sequentially-linked phases within a process of employee resourcing, which itself may be located within a wider HR management strategy. Bratton and Gold (2007, p 239) differentiate the two terms while establishing a clear link between them in the following way:

‘Recruitment is the process of generating a pool of capable people to apply for employment to an organisation. Selection is the process by which managers and others use specific instruments to choose from a pool of applicants a person or persons more likely to succeed in the job(s), given management goals and legal requirements.’

In setting out a similar distinction in which recruitment activities provide a pool of people eligible for selection, Foot and Hook (2005, p 63) suggest that:

although the two functions are closely connected, each requires a separate range of skills and expertise, and may in practice be fulfilled by different staff members. The recruitment activity, but not normally the selection decision, may be outsourced to an agency. It makes sense, therefore, to treat each activity separately.

Recruitment and selection, as defined here, can play a pivotally important role in shaping an organisations effectiveness and performance, if work organisations are able to acquire workers who already possess relevant knowledge, skills and aptitudes and are also able to make an accurate prediction regarding their future abilities. If we accept this premise (which will be questioned to some extent in this chapter), recruiting and selecting staff in an effective manner can both avoid undesirable costs – for example those associated with high staff turnover, poor performance and dissatisfied customer’ – and engender a mutually beneficial employment relationship characterised, wherever possible, by high commitment on both sides.

A Topical and Relevant Area

Recruitment and selection is a topical area. While it has always had the capacity to form a key part of the process of managing and leading people as a routine part of organisational life, it is suggested here that recruitment and selection has become ever more important as organisations increasingly regard their workforce as a source of competitive advantage. Of course, not all employers engage with this proposition even at the rhetorical level. However, here is evidence of increased interest in the utilisation of employee selection methods which are valid, reliable and fair. For example, it has been noted that ‘over several decades, work psychology has had a significant influence on the way people are recruited into jobs, through rigorous development and evaluation of personnel selection procedures’ (Arnold et al, 2005, p 135). In this chapter we will examine several contemporary themes in recruitment and selection including what is human as the competency approach and online recruitment.

Recruitment and selection does not operate in a vacuum, insulated from wider social trends, so it is very important to keep abreast of current research. A CIPD annual survey report, Recruitment, Retention and Turnover (2009d), showed how the financial crisis was biting in the field of HRM. The survey concluded that half of the companies surveyed claimed that the recession was having a negative impact on their employee resourcing budgets and activities. 56 per cent of organisations were focusing more on retaining than recruiting talent, while four out often said that they would recruit fewer people in the forthcoming year. Interestingly, 72 per cent of respondents thought that employers would ‘use the downturn’ as an opportunity to get rid of poor performers and bring about culture change. These specific findings epitomise the very close link between recruitment and selection and the wider social and economic context.

This aspect of employee resourcing is characterised, however, by potential difficulties. Many widely-used selection methods – for example, interviewing are generally perceived to be unreliable as a predictor of jobholders’ performance in reality. Thus it is critically important to obtain a realistic evaluation of the process from all concerned, including both successful and unsuccessful candidates. There are ethical issues around selecting ‘appropriate’, and by implication rejecting ‘inappropriate’, candidates for employment. Many organisations seek to employ people who will ‘fit in’ with their organisation’s culture (French et al, 2008) – see also the lKEA case study below. This may be perfectly understandable. However, it carries important ethical overtones – for example, whether an employing organisation should be involved in shaping an individual’s identity. We put forward the view in this chapter that, notwithstanding the moral issues and practical difficulties outlined here, recruitment and selection is one area where it is possible to distinguish policies and practices associated with critical success factors and performance differentiators which, in turn, impact on organisational effectiveness in significant ways.

What work at IKEA?

The following extracts are taken from the IKEA Group corporate website ‘Why work at IKEA?’ section.

Because of our values, our culture and the endless opportunities, we believe that it’s important to attract, develop and inspire our people. We are continuously investing in our co-workers and give them sufficient opportunities and responsibility to develop.

What would It be like to work at Ikea?

You’d be working for a growing global company that shares a well-defined and well-communicated vision and business idea.

You’d be able to develop your skills in many different ways, becoming an expert at your daily work, by taking new directions in other parts of the company, or by taking on greater responsibility, perhaps even in another country.

Human values and team spirit are part of the work environment. You’d not only have fun at work, you’d be able to contribute to the development of others.

At IKEA you’d be rewarded for making positive contributions.

You’d have the chance to grow and develop together with the company.

Values at the heart of our culture

The people and the values of IKEA create a culture of informality, respect, diversity and real opportunities for growth. These values include:

Togetherness and enthusiasm

This means we respect our colleagues and help each other in difficult times. We look for people who are supportive, work well in teams and are open with each other in the way they talk, interact and connect. IKEA supports this attitude with open-plan offices and by laying out clear goals that co-workers can stand behind.

Humbleness

More than anything this means respect. We are humble towards our competitors, respecting their proficiency, and realising that we constantly have to be better than they are to keep our market share. It also means that we respect our co-workers and their views, and have respect for the task we have set ourselves.

Willpower

Willpower means first agreeing on mutual objectives and then not letting anything actually stand in the way of actually achieving them. In other words, it means we know exactly what we want, and our desire to get it should be irrepressible.

Simplicity

Behind this value are ideas like efficiency, common-sense and avoiding complicated solutions. Simple habits, simple actions and a healthy aversion to status symbols are part of IKEA.

Source: www.ikea.com. Used with the kind permission of IKEA.

Questions

- In what ways could an employer seek to asses qualities of togetherness, humbleness, willpower and simplicity among candidates in the course of a recruitment and selection process? How accurate do you think judgements made along these lines are likely to be?

- What selection methods could IKEA employ to assess whether potential workers can ‘develop skills’ and ‘take on new directions and responsibilities’?

- To what extent should an organisation like IKEA attempt to recruit and select workers who embody their organisational culture? Give reasons for your answer. Identify some possible negative outcomes of aligning selection with organisational culture.

Effective Recruitment and Selection

We have already referred to the potential importance of recruitment and selection as an activity. Pilbeam and Corbridge (2006, p 142) provide a useful overview of potential positive and negative aspects noting that: ‘The recruitment and selection of employees is fundamental to the functioning of an organisation, and there are compelling reasons for getting it right. Inappropriate selection decisions reduce organisational effectiveness, invalidate reward and development strategies, are frequently unfair on the individual recruit and can be distressing for managers who have to deal with unsuitable employees.’

Reflective Activity

Getting it wrong

In an attempt to check the robustness of security procedures at British airports, Anthony France, a reporter for The Sun newspaper, obtained a job as a baggage handler with a contractor subsequently named by the newspaper In the course of his selection, France gave bogus references, and provided a fake home address and bank details Throughout the selection process he lied about his past while details of his work as an undercover journalist were available on the Internet.

France then proceeded to take fake explosive material onto a holiday jet airliner at Birmingham International Airport.

This case provides a good, albeit extreme, example of the possible consequences of flawed selection procedures, or as happened here, when agreed practices, such as checking personal details, are not put into effect. Such consequences are potentially wide-ranging and veer from the trivial and comic to possibly tragic outcomes. One can certainly reasonably anticipate many of the negative outcomes listed below to follow when the predictions made about a candidate for employment fail to be borne out.

It is undoubtedly true that recruitment and selection strategies and practices have important consequences for all concerned, so what are the keys to maximising the chances of effective recruitment and selection? Some important factors are listed below.

Recognizing the Power of Perception

Perception is defined as the process by which humans receive, organise and make sense of the information they receive from the outside world (Buchanan and Huczynski, 2007; French et al, 2008; and Rollinson, 2008). The quality or accuracy of our perceptions will have a major impact on our response to a situation. There is much data suggesting that when we perceive other people particularly in an artificial and time-constrained situation like a job interview we can make key mistakes, sometimes at a subliminal level. One key to enhancing effectiveness in recruitment and selection, therefore, lies in an appreciation of some core principles of interpersonal perception and, in particular, of some common potential mistakes in this regard.

- Selective perception. Our brains cannot process all of the information which our senses pick up so we instead select particular objects – or aspects of people for attention. We furthermore attribute positive or negative characteristics to the stimuli: known as the ‘halo’ and ‘horns’ effect respectively. For example, an interviewee who has a large coffee stain on their clothing, but is otherwise well-presented, may have difficulty creating a positive overall impression despite the fact that it might be that their desire for the new job that resulted in nervousness and clumsiness.

- Self-centred bias. A recruiter should avoid evaluating a candidate by reference to himself or herself because this may be irrelevant to the post in question and run the risks of a ‘clone effect’ in a changing business environment. The sentence ‘I was like you 15 years ago’ may be damaging in a number of respects and should not be the basis for employment in most situations.

- Early information bias. We often hear apocryphal stories of interview panels making very early decisions on candidates’ suitability and spending the remaining time confirming that decision. Mythical though some of these tales may be, there is a danger of over-prioritising early events - a candidate who trips over when entering an interview room may thus genuinely be putting themselves at a disadvantage.

- Stereotyping. This is a common short cut to understanding an individual’s attributes, which is a difficult and time-consuming process, because we are all unique and complex beings. The logic of stereotyping attributes individuals’ characteristics to those of a group they belong to - for example, the view that because Italians are considered to be emotional, an individual Italian citizen will be too. Stereotypes might contain elements of truth; on the other hand they may be entirely false since we are all unique. Everyone is different from everyone else. Stereotyping may well be irrelevant, therefore, and if acted on, also discriminatory.

It should be stressed that these, and other, perceptual errors are not inevitable and can be overcome. Many HR professionals study subjects like organisational behaviour as part of their career qualifications in which they are made aware of the dangers of inaccurate perception. Nonetheless, it remains the case that an understanding of this subject area is an important building block to effective recruitment and selection.

Taking a Staged Approach

Much prescriptive writing on recruitment and selection advocates viewing the process as sequential with distinct and inter-linked stages. This model is referred to as the resourcing cycle. The resourcing cycle begins with the identification of a vacancy and ends when the successful candidate is performing the job to an acceptable standard: ie post-selection. It is a two-way process. Organisations are evaluating candidates for a vacancy, but candidates also observe the organisation as a prospective employer. Conducting the process in a professional and timely manner is necessary for normal effectiveness in helping to ensure that not only is the ‘best’ candidate attracted to apply and subsequently accepts the post, but also that unsuccessful candidates can respect the decision made and possibly apply for future vacancies, along with other suitable candidates.

The first step in the recruitment process is to decide that there is a vacancy to be filled. Increasingly a more strategic and questioning approach may be taken. If, for example, the vacancy arises because an employee has left, managers may take the opportunity to review the work itself and consider whether it could be undertaken in an alternative way. For example, could the work be done on a part-time, job-share or flexi-time basis? Alternatively, could the job could be automated? The financial services sector in the UK provides one example of where technological developments have resulted in both significant job losses and changed patterns of work since 1990.

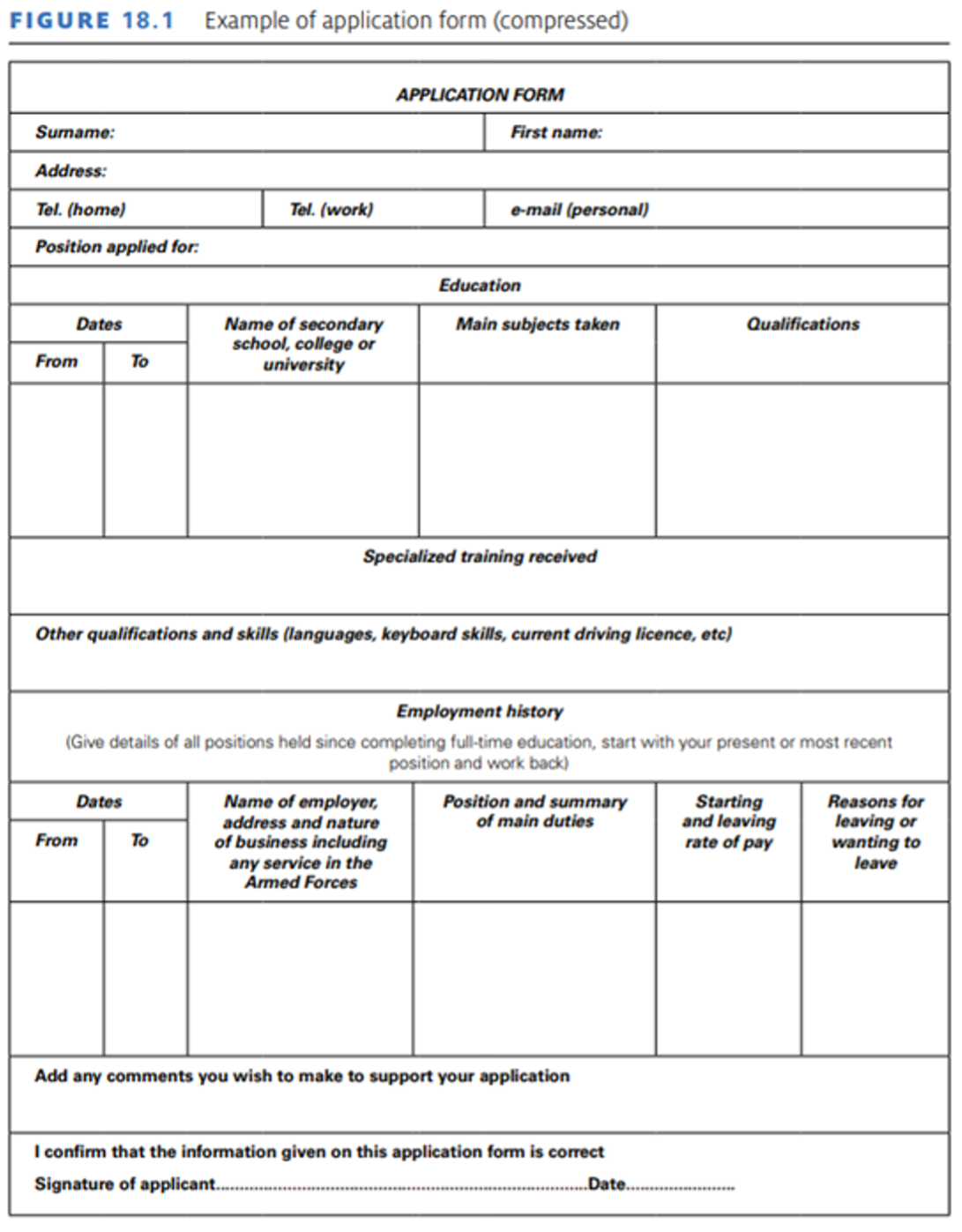

On the assumption that a post does need to be filled it will be necessary to devise specifications. Whether a competency-based approach (this concept will be defined later in the chapter) or the more traditional method of formal job descriptions and person specifications is chosen, a CIPD report (2007c) notes that specifications need to reflect the duties and requirements of the job along with the skills, aptitudes, knowledge, experience, qualifications and personal qualities that are necessary to perform the job effectively. Consideration should also be given to how the recruiter intends to measure and elicit information regarding those skills. Are they essential to job performance or merely desirable, and can they be objectively measured?

Attracting Candidates

The next stage in the recruitment cycle is the attraction of candidates, as one important objective of a recruitment method is to produce an appropriate number of suitable candidates within reasonable cost constraints. Pilbeam and Corbridge (2006, p 151) note that ‘There is no ideal number of applications and no intrinsic value in attracting a high volume of candidates.’ Neither is there a single best way to recruit applicants. Rather the chosen recruitment medium needs to ensure that there are a sufficient number of suitably qualified candidates from which to make a selection without being overwhelmed with large numbers of unsuitable applications. Using a recruitment agency to find a small number of suitable candidates, particularly for senior or specialised posts, may prove a significantly more cost-effective and efficient method than a major advertising campaign which generates a large response from unsuitable candidates. The choice of method will also be influenced by the availability of candidates – that is, is there likely to be a shortage or surplus of candidates? For example, in the period around 2005 there was a large pool of Polish migrant workers wanting to work in Britain, but within four or five years this had significantly diminished as employers found some applicants were being more selective, while other potential Polish workers had returned home after the financial and economic crisis took hold in the UK after 2008.

Reflective Activity

Look at the recruitment section of your local newspaper. What sort of vacancies are typically advertised here? Compare and contrast these with the types of vacancies advertised in broadsheet newspapers such as The Times or Daily Telegraph. What indicators are there in the wording of advertisements as to whether there is a surplus or shortage of candidates?

Which method of recruitment should be adopted? There is no single best way, and a contingency approach involving an analysis of what might be effective in particular circumstances is advocated: ie ‘it all depends’.

Some organisations, for example in the local government sector, will always advertise all vacancies to ensure equality of opportunity whilst manufacturing organisations tend to rely on recruitment agencies (CIPD, 2007c). Human resources professionals should carefully consider and review which methods have been most effective in the past and which method or methods would be most appropriate for the current vacancy. They should also, critically, keep new methods under review, including, for example, the growing trend towards Internet-based recruitment.

Selection

One of the last stages in recruitment and selection is selection itself, which includes the choice of methods by which an employer reduces a short-listed group following the recruitment stage, leading to an employment decision. For most people, this is the only visible stage of the resourcing cycle because their experience of it is likely to be as a subject – or candidate – rather than involvement in planning the entire process. While recruitment can be perceived as a positive activity generating an optimum number of job-seekers, selection is inherently negative in that it will probably involve rejection of applicants.

It would be prudent to argue that selection decisions should be based on a range of selection tools as some have poor predictive job ability. While it is almost inconceivable that employment would be offered or accepted without a face-to-face encounter, many organisations still rely almost exclusively on the outcome of interviews to make selection decisions.

To have any value, interviews should be conducted or supervised by trained individuals, be structured to follow a previously agreed set of questions mirroring the person specification or job profile, and allow candidates the opportunity to ask questions. The interview is more than a selection device. It is a mechanism that is capable of communicating information about the job and the organisation to the candidate, with the aim of giving a realistic job preview, providing information about the process, and thus can minimise the risk of job offers being rejected. Organisations seeking high performance in their selection processes should therefore give considerable attention to maximising the uses of the interview and, ideally, combine this method with other psychometric measures where appropriate.

Validity of Selection Methods

It may appear self-evident that organisational decision-makers will wish to ensure that their recruitment (and in this case) selection methods are effective. We have already suggested, however, that making judgements on an individual’s personal characteristics and suitability for future employment is inherently problematic and that many ‘normal’ selection methods contain significant flaws. There is also the question of what is meant by the terms ‘reliability’ and ‘validity’ when applied to recruitment and selection.

Reliability in the context of workforce selection can refer to the following issues:

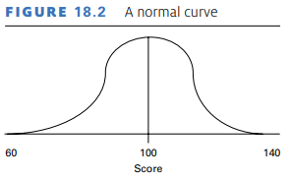

- Temporal or ‘re-test’ stability where the effectiveness of a selection tool is assessed by consistency of results obtained over time. An individual could for example complete a personality inventory or intelligence test at different times over a period of several years, although in the latter case it would be important to isolate the impact of repeated practice on results.

- Consistency – that is, does the test measure what it sets out to? Some elements of IQ tests have for example been criticised for emphasising a person’s vocabulary which might in turn be influenced by their education and general background rather than by their innate intelligence.

Validity in this area is typically subdivided into the following aspects:

- Face validity has an emphasis on the acceptability of the selection measure, including to the candidate himself or herself. For example, it is possible (although extremely unlikely) that there is a correlation between a person’s hat size and his/her job competence. However, you would be reluctant to measure candidates’ heads as part of their selection due to their probable scepticism at the use of this measure.

- Content validity refers to the nature of the measure and in particular its adequacy as a tool. For example, the UK driving test could be criticised for not assessing ability in either night driving or travelling on motorways.

- Predictive validity centres on linkages between results or scores on a selection measure and subsequent outcome – most commonly, job performance at a future point. Here it is important to identify when the comparison will be made – ie immediately in the case of a simple job requiring little training, or more commonly, at an intermediate point, possibly after a suitable probationary period.

We argue here that validity, along with fairness, should be the overriding indicator of a selection method for high performance organisations and that it is important to obtain sophisticated data on validity in all its forms. Pilbeam and Corbridge (2006, p 173) provide a summary of the predictive validity of selection methods based on the findings of various research studies.

| 1.0 | Certain prediction |

| 0.9 | |

| 0.8 | |

| 0.7 | Assessment centres for development |

| 0.6 | Skilful and structured interviews |

| 0.5 | Work sampling Ability tests |

| 0.4 | Assessment centres for job performance Biodata Personality assessment |

| 0.3 | Unstructured interviews |

| 0.2 | |

| 0.1 | References |

| 1.1 | Graphology Astrology |

However, they suggest that these validity measures should be treated with caution because they can be affected by the performance indicators used, and by the way the tools were applied. They indicate nonetheless both variability between measures and some overall degree of uncertainty when predicting future work performance during the selection process.

While it is recommended that validity should be the prime factor in choosing selection tools, it would be naïve not to recognise that other factors such as cost and applicability may be relevant. How practical, therefore, is it to conduct any particular measure? As indicated earlier, an organisation aiming for high performance is recommended to adopt valid measures as opposed to merely practical or less costly ones. Again, one should recognise that recruitment and selection is contingent upon other factors such as the work itself. A ‘high performance’ organisation in the fast-food industry may legitimately decide not to adopt some relatively valid but expensive methods when selecting fast-food operatives. It should be noted that the oft-derided method of interviewing can in reality be a relatively valid method if conducted skilfully and structured.

Recruitment and Selection: Art or Science?

Systematic models of recruitment and selection based on a resourcing cycle should not necessarily imply that this process is underpinned by scientific reasoning and method. As we have seen, Pilbeam and Corbridge note that even the most valid methods fall some way short of complete predictive validity. Thompson and McHugh (2009) go further, taking a critical view on the general use and, in particular, the validity of employee selection methods. In commenting on the use of personality tests in selection, these authors state that in utilising such tests employers are essentially ‘clutching at straws’ and on this basis will probably use anything that will help them make some kind of systematic decision. These authors identify now discredited selection methods, such as the use of polygraphs to detect lying and other methods such as astrology, which are deemed more appropriate in some cultures than in others. It is indeed important to keep in mind that today’s received wisdom in the area of recruitment and selection, just as in the management canon more generally, may be criticised and even widely rejected in the future.

The process of recruitment and selection continues nonetheless to be viewed as best carried out via sequential but linked stages of first gathering a pool of applicants, a screening-out process, followed by the positive step of actual selection. This apparently logical ordering of the activities is largely viewed as essential to achieve minimum thresholds of effectiveness.

Induction and Transition

It is not always the case that selected employees are immediately capable of performing to the maximum level on their allotted job(s): important stages in the resourcing cycle occur post-selection. Many organisations when selecting are making a longer-term prediction of a new employee’s capability. This accounts for many organisations’ imposing a probationary period in which employees’ performance and future potential can be assessed in the work setting. The resourcing cycle extends into this post-selection phase and the induction period and early phases of employment constitute a critically important part of both successful integration into the workplace culture and development as a fully functioning worker. The final stage of the resourcing cycle involves evaluation of the process and reflection on lessons learned from the process and their implications for the future.

Recruitment Costs

A concern with effectiveness in recruitment and selection becomes all the more important when one considers the costs of getting things wrong. We begin with apparent costs, which centre on the direct costs of recruitment procedures, but one might also consider the so-called opportunity costs of engaging in repeated recruitment and selection when workers leave an organisation. An excessive preoccupation with recruitment and selection will divert a manager from other activites he or she could usefully be engaged in. It is also useful to consider the ‘investment’, including training resources, lost to the employer when a worker leaves prematurely. The CIPD survey report Recruitment, Retention and Turnover (2009d) estimates the average direct cost of recruitment per individual in the UK in 2009 as £4,000 – increasing to £6,125 when organisations are also calculating the associated labour turnover costs. For workers in the managerial and professional category, these costs were considerably higher: £7,750, rising to £11,000.

Implicit costs are less quantifiable and include the following categories:

- Poor performance

- Reduced productivity

- Low-quality products or services

- Dissatisfied customers or other stakeholders

- Low employee morale.

The implicit costs mentioned here are, in themselves, clearly undesirable outcomes in all organisations. In high-performing organisations ‘average’ or ‘adequate’ performance may also be insufficient and recruitment and selection may be deemed to have failed unless workers have become ‘thinking performers’.

Contemporary Themes in the Recruitment and Selection

The Competency Approach

Typically decisions on selecting a potential worker are made primarily with a view to taking on the most appropriate person to do a particular job in terms of their current or, more commonly, potential competencies. In recent years this concept has been extended to search for workers who are ‘flexible’ and able to contribute to additional and/or changing job roles. This approach contrasts with a more traditional model which involves first compiling a wide-ranging job description for the post in question, followed by the use of a person specification, which in effect forms a checklist along which candidates can be evaluated on criteria such as knowledge, skills and personal qualities. This traditional approach, in essence, involves matching characteristics of an 'ideal' person to fill a defined job. There is a seductive logic in this apparently rational approach. However, there are in-built problems in its application if judgements of an individual’s personality are inherently subjective and open to error and, furthermore, if these personal characteristics are suited to present rather than changing circumstances.

The competencies model in contrast, seeks to identify abilities needed to perform a job well rather than focusing on personal characteristics such as politeness or assertiveness. Torrington et al (2008, p 170) identify some potentially important advantages of referring to competencies in this area noting that:

‘they can be used in an integrated way for selection, development, appraisal and reward activities; and also that from them behavioural indicators can be derived against which assessment can take place.’

Competency-based models are becoming increasingly popular in graduate recruitment where organisations are making decisions on future potential. Farnham and Stevens (2000) found that managers in the public sector increasingly viewed traditional job descriptions and person specifications as archaic, rigid and rarely an accurate reflection of the requirements of the job. There is increasing evidence that this popularity is more widespread. A CIPD report (2007c) found that 86 per cent of organisations surveyed were now using competency-based interviews in some way; and in another survey, over half of employers polled had started using them in the past year (William, 2008). It is suggested that the competency-based model may be a more meaningful way of underpinning recruitment and selection in the current fast-moving world of work and can accordingly contribute more effectively to securing high performance.

Flexibility and Teamwork

Many commentators refer to significant changes in the world of work and the implications these have for the recruitment and selection of a workforce.

Searle (2003, p 276) notes that:

‘Increasingly employees are working in self-organised teams in which it is difficult to determine the boundaries between different jobholders’ responsibilities. The team undertakes the task and members co-operate and work together to achieve it. Recruitment and selection practices focus on identifying a suitable person for the job, but ... isolating a job’s roles and responsibilities may be difficult to do in fast-changing and team-based situations.’

There is here an implication both that teamworking skills could usefully be made part of employee selection and also that an individual’s job specification should increasingly be designed and interpreted flexibly. It can plausibly be posited that we now inhabit a world of work in which unforeseen problems are thrown up routinely and on an ongoing basis and where there is seldom time to respond to them in a measured fashion (Linstead et al, 2009). In this type of business environment, decisions made can be ‘rational’ in terms of past practice and events but may in fact be revealed to be flawed or even obsolete when they are made in the new context.

If we accept this analysis of work in the 21st century, there is therefore an implication that organisations aiming for high performance may need to use selection methods which assess qualities of flexibility and creative thinking (irrespective of whether they are using a traditional or competency recruitment and selection model). Of course, many jobs may still require task-holders to work in a predictable and standardised way, so one should exercise caution when examining this rhetoric. Interestingly, however, recruitment and selection practices should themselves be kept under constant review if we accept the reality of a business world characterised by discontinuous, rather than incremental, change.

Case Study

An Alternative Approach: "Talent Puddles" at Nestlé

Many organisations are faced with the problem of how to create a pool of talent from which to select candidates. Jobs requiring specialist skills and knowledge can often take several months and considerable costs to fill, yet often suitable candidates have slipped through the organisations net because there wasn’t a vacancy at that particular time. Creating ‘talent pools’ or databases of good applicants is one way organisations have tried to keep potential candidates interested but in many cases this has been no more than keeping CVs on file which are never referred to or seen again. Nestlé, the large global food and beverage manufacturer, has taken a more radical approach to managing talent by creating ‘talent puddles’. Whilst these are similar to talent pools, Nestlé’s approach has focused on creating a talent bank in specific areas of the business where there is a shortage of skilled applicants. Talent puddles focus on ‘talent gaps’ – specific jobs and difficult-to-fill roles – by creating a small puddle of talent that can be readily brought into the business, thus reducing the costs and speeding up the recruitment process.

The initiative began with the supply chain function which now contains 120 shortlisted candidates and has placed eight people but has since been extended to other areas of the business. This approach to resourcing has also changed the recruiters’ role. A significant portion of their time is now spent calling people and sifting through CVs from the talent puddle. When people apply, recruiters look at the quality of the applications and assess what level/grade they are operating at, ranking and recording them accordingly. Candidates are met and interviewed by the recruitment team and line managers before being placed in the talent puddle. One could argue that in effect the organisation has created its own internal recruitment agency and there is no doubt that this approach has significantly reduced the company’s reliance on recruitment agencies over the past five years. However, just like recruitment agencies, one could also question how you keep 120 highly skilled potential candidates interested if you don’t have an actual vacancy.

Adapted from CIPD Annual Survey Report 2007(c) Recruitment, Retention and Turnover, p 10. London: CIPD.

Recruiting in the Virtual World

The rise in the use of the Internet is probably the most significant development in the recruitment field in the early 21st century. Various surveys (CIPD, 2007c; IRS, 2008) now suggest that this is fast becoming employers’ preferred way of attracting applicants. For example, 75 per cent of companies are now using their corporate website as their most common method (along with local newspaper advertising) of attracting candidates (CIPD, 2007). There is, however, little evidence that the Internet produces better-quality candidates, but it does deliver more of them and more employers report that online recruitment made it easier to find the right candidate (Crail, 2007). Candidates themselves are increasingly choosing this medium to search for jobs, with 89 per cent of graduates only searching online for jobs (Reed Employment, reported in People Management, 20 March 2008).

The benefits of online recruitment to employers include the speed, reduced administrative burden and costs, and no geographical limits. The benefits to applicants are that it is easier, faster and more convenient to post a CV or search a job site online than to read a selection of printed media (Whitford, 2003). his is all very well if you have skills that are highly in demand, but if employers are tending to post vacancies on their own websites, candidates still have to trawl the web in order to find vacancies and even ‘web savvy’ applicants may be deterred by the perceived impersonal nature of online recruitment. Also there are still some people who are either not comfortable using the Internet or do not have ready access to a computer. Thus there is still a role then for conventional advertising (IDS, 2006).

Whatever the pros and cons, online recruitment continues to expand and employers are now combining more traditional methods with online recruitment by using printed adverts to refer jobseekers to an Internet vacancy (Murphy, 2008). Other employers such as Microsoft are enhancing its brand visibility and credibility by having a wider Internet recruitment presence. Microsoft uses its online tools to impact and influence its public image and reach a broader audience and thus create a diverse workplace with varied skills and talents. One initiative is the introduction of ‘corporate recruitment blogs’. The idea is that potential job candidates may be attracted to the company through what they see on the blog and make contact through the specific blogger who will initiate the recruitment process on behalf of the company (Hasson, 2007). See also the Cadbury Schweppes example below.

Reflective Activity

Is online chat the way forward with recruitment?

Graduates today have a higher expectation of being able to use social networking as a primary source of information and communication. In response to this Cadbury Schweppes launched its 2008 UK graduate recruitment campaign with a new online chatroom to give potential applicants the chance to interact with the company’s current graduates The confectionary giant has created an easy-to-use site that allows potential graduates the opportunity to chat online and put questions to its graduate recruitment team. The site builds on the success the company had with its graduate blogs in 2005 and MP3 downloads in 2006. Chatroom sessions are advertised on the firm’s graduate recruitment calendar and the team have about eight hours of online dedicated chat to interested graduates (Berry, 2007). Would you use an employer’s chatroom?

Fairness in Recruitment and Selection

One factor shared by both traditional and competence models of recruitment and selection is that both are framed by an imperative to take on the most appropriate person in terms of their contribution to organisational performance. This is, of course, unsurprising given the preoccupation of organisations in all sectors with meeting objectives and targets. However, when we consider what is meant by making appropriate selection decisions, other factors, including fairness, can also be seen to be important.

Decisions made in the course of a recruitment and selection process should be perceived as essentially fair and admissible to all parties, including people who have been rejected. There is evidence to support the view that applicants are concerned with both procedural justice - that is, how far they felt that selection methods were related to a job and the extent to which procedures were explained to them – and distributive justice, where their concern shifts to how equitably they felt they were treated and whether the outcome of selection was perceived to be fair (see Gilliland, 1993).

Fairness in this regard can be linked to the actual selection methods used. Anderson et al (2001) found that interviews, resumes, and work samples were well-regarded methods, while handwriting tests (graphology) were held in low regard. Personality and ability tests received an ‘intermediate’ evaluation. This is linked to the concept of face validity: how plausible and valid does the method used appear to the candidate under scrutiny? It is reasonable to suggest that employers should take care in choosing selection methods in order to maintain credibility among applicants as well, of course, as assessing the predictive value of the methods.

Fairness in selection also extends to the area of discrimination and equal opportunities, as we saw in Chapter 4. In the UK, for example, current legislation is intended to make unlawful discrimination on the grounds of age, race, nationality or ethnic origin, disability, sex, marital status and sexual orientation. The law identifies both direct discrimination, where an individual is treated less favourably on the sole grounds of their membership of a group covered in the relevant legislation, and indirect discrimination which occurs when a provision applied to both groups disproportionately affects one in reality. The Equality and Human Rights Commission highlights headhunting as one area in which indirect discrimination may occur. Headhunters may, in approaching individuals already in jobs, contravene this aspect of the law if existing jobs are dominated by one sex or ethnic group, for example. Compliance with equal opportunities legislation provides one example of performance infrastructure and would, it is surmised, reap business benefits - ie recruiting from the truly qualified labour pool and avoiding negative outcomes such as costly and reputation-damaging legal processes.

High-performance organisations may seek to go beyond the compliance approach and work towards a policy or even strategy of managing diversity (see also Chapter 11). As defined by the CIPD (2006) a managing diversity approach:

is about ensuring that all employees have an opportunity to maximise their potential and enhance their self-development and their contribution to the organisation. It recognises that people from different backgrounds can bring fresh ideas and perceptions, which can make the way work is done more efficient and make products and services better. Managing diversity successfully will help organisations to nurture creativity and innovation and thereby to tap hidden capacity for growth and improved competiveness.

It is thus important to ensure such a policy is operationalised in the field of recruitment and selection because staff involved in this activity can be said to act as ‘gatekeepers’ of an organisation.

Case Study

Opportunities for All At ASDA

The following statement is an extract from the ‘Opportunities for All’ section of Asda’s corporate website, accessed September 2004.

At ASDA we endeavour to discriminate only on ability and we recognise that our organisation can be effective if we have diverse colleague base, representing every section of society.

We want to recruit colleagues and managers who represent the communities in which we operate and the customers we serve.

Ethnic minorities

We have been working at all levels to make sure that ethnic minorities are represented across all levels of our business and we operate a policy of Religious Festival Leave so that any colleague can apply to take up to two days unpaid leave to attend their Religious Festival.

Women

We recognise that there are mutual benefits in making sure we employ women in our workplace. Besides our equal opportunities recruitment policy we have a number of other initiatives which support our commitment, particularly our flexible working practices which include job shares and part time working at all levels, parental leave, shift swaps and career breaks.

Disability

It is our aim to make sure that our stores are accessible for disabled people to both work and shop in. As a company we have been awarded the Two Tick symbol and we have a good working partnership with Remploy and we work together to help disabled people get back into the work place. We offer people with disabilities a working environment which is supportive and we operate an equal opportunities policy on promotion.

If, due to your disability, you need some help whether completing your application form or during the interview process, please contact the people manager in your local store or depot who will be pleased to help.

Age

The proportion of older people in the population is steadily Increasing and we’re seeing this reflected in the age profile of our workforce. We want to encourage the recruitment and retention of older, experienced colleagues, many of whom welcome the opportunity to work beyond the traditional retirement age, to work flexibly and enjoy a phased retirement.

We’ve been encouraging stores and depots to recruit more mature colleagues or ‘Goldies’ and in one new store in Broadstairs we opened with over 40 per cent of our colleagues aged so or over. And we have seen a reduction in both labour turnover and absence well below average in the store.

To further reinforce our commitment we also offer a number of flexible working schemes such as Benidorm Leave where older colleagues can take three months unpaid leave between January and March, or grandparents leave where colleagues who are grandparents take up to a week off unpaid to look after a new arrival.

Used with the kind permission of ASDA Ltd.

Questions

- To what extent does this statement from Asda’s website indicate that his organisation has a strategy fur diversity management? What has led you to your conclusion?

- How do Asda seek to safeguard their ‘Opportunities for All’ policy the area of recruitment and selection?

- Produce a statement for use by companies setting out employment policy in the area of age discrimination and indicate how this could take effect in the recruitment and selection of workers.

The Extent of Professional Practice

Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises

There is evidence to suggest that many human resources management (HRM) practices often prescribed in the academic literature are more common in some sectors of business than others, and that the small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) group, in particular, are less likely to have in-house HR expertise and sophisticated systems in place (Cully et al, 1999). A study carried out by Cassell et al (2002) in SMEs in the north of England focused on both the use and perceived value (by employers) of a range of HRM procedures. In the area of recruitment and selection, only 31 per cent of firms in the sample used wide-ranging employee development and recruitment and selection procedures. Interestingly, 38 per cent of the sample questioned said that they did not use recruitment and selection procedures at all. In the companies that did make use of them, 50 per cent found that the procedures helped ‘entirely’ or ‘a lot’ in over half of the instances in which they are used. This is some way from the picture of widespread use and the assumed universal benefits conveyed in some sources.

The reality of the context faced by managers of SMEs will cause them to frame their responses in an entirely understandable way, and prescriptive ‘textbook style’ approaches may be viewed as inappropriate. It would, of course, be as damaging for SMEs as for any other organisation if a lack of ‘high-quality’ practices in recruitment and selection were seen to inhibit performance and, indeed, SMEs have often been criticised for the lack of a proactive and integrated approach to managing people. However, any assumption that universally applicable approaches to recruitment and selection are needed may ignore the distinctive processes and practices faced by particular organisations.

Reflective Activity

Lack of skill a major factor in UK recruitment and selection difficulties

A CIPD survey (2008c) reported that 86 per cent of British organisations were having difficulty filling vacancies in spite of the financial and economic crisis which hit I that year. In part, this was the result of a ‘skills crunch’ with 70 per cent of the research sample citing a lack of necessary candidate skills as the main reason for recruitment difficulties. However, only half of the surveyed companies had a formal resourcing strategy to counter the skills-gap problem and struggles to recruit top talent.

Deborah Femon of the CIPD also pointed to the importance of the retention of talented workers, noting that ‘Organisations should have a look at their learning and development strategies which can help met the business demands in two ways. Firstly, those employers who have development opportunities are more likely to stay, which reduces turnover. Secondly, a good learning and development culture will foster a strong employer brand, helping to attract key talent.’

This research highlights the importance of referring to contemporary evidence when analysing recruitment and selection in general terms, and also points to the importance of the post-selection phase in retaining staff.

Recruitment and Selection: A Contingency Approach

The underlying principle that organisational policies and practices need to be shaped within a particular context is often referred to as the contingency approach. The argument put forward within this viewpoint is that successful policies and strategies are those which apply principles within the particular context faced by the unique organisation.

One example of a ‘contingent factor’ which can impact upon recruitment and selection is national culture. French (2010) draws attention to important cross-cultural differences in the area. For example, different cultures emphasise different attributes when approaching the recruitment and selection of employees. It is also the case that particular selection methods are used more or less frequently in different societies – see also Perkins and Shortland (2006). So in individualistic cultures such as the USA’s and UK’s, there is a preoccupation with selection methods which emphasise individual differences. Many psychometric tests can indeed be seen to originate from the USA. Furthermore, in a society which emphasises individual achievement as opposed to ascribed status (eg through age or gender), one might expect a raft of legislation prohibiting discrimination against particular groups. Here the expectation is that selection should be on the basis of individual personal characteristics or qualifications. This may contrast with more collectivist societies, for example China, where personal connections may assume a more prominent role. Bjorkman and Yuan (1999) conducted one of several studies which reached this overall conclusion. It may also be true that selection methods are given varying degrees of face validity in different societies. A CIPD survey (2004c) on graphology discovered that while relatively few companies in the UK used graphology as a trusted method of selecting employees, its adoption was far more widespread, common and therefore accepted in other countries, including France.

In summary, the contingency approach with the underlying message that managing people successfully depends on contextual factors – ‘it all depends’ can readily be applied to the area of recruitment and selection. The increasingly large number of organisations operating across national boundaries, or who employ workers from different cultural backgrounds, can benefit from formulating policies within an awareness of cultural difference.

Recruitment and Selection and Organizational Culture

It is unsurprising that the culture of a particular work organisation will influence selection decisions, with recruiters both consciously and unconsciously selecting those individuals who will ‘best fit’ that culture. In some organisations recruitment policy and practice is derived from their overall strategy which disseminates values into the recruitment and selection process. Mullins (2007, p 727) provides the example of Garden Festival Wales, an organisation created to run for a designated and short time-period. This organisation’s managers were particularly concerned to create a culture via recruitment of suitable employees. This is an interesting example because this organisation had no prior history and it indicates the power of recruitment and selection in inculcating particular cultural norms.

Other research has demonstrated that individuals as well as organisations seek this ‘best fit’, providing evidence that many individuals prefer to work in organisations that reflect their personal values. Judge and Cable (1997) and Backhaus (2003) found that job-seekers may actively seek a good ‘person-organisation fit’ when considering prospective employers. This, of course, provides further support for the processual two-way model of recruitment and selection. However, justifying selection decisions on the basis of ‘cultural fit’ means that there are ethical issues to consider in terms of reasons for rejection: are organisations justified in determining who does and does not ‘fit’? It may be that practical concerns also emerge – for example, in the danger of maintaining organisations in the image of current role models – which may be inappropriate in the future. Psychologists have also long recognised the threat posed by ‘groupthink’ where innovation is suppressed by a dominant group and an ‘emperor’s new clothes’ syndrome develops, with individuals reluctant to voice objections to bad group decisions.

Reflective Activity

Return to the IKEA case study at the start of this chapter.

IKEA put great stress upon recruiting employees who will complement their organisational culture.

- What are the potential benefits of selecting a workforce in terms of an organisation’s culture?

- What are the philosophical and practical arguments against selection based on values and work culture?

Conclusion

This chapter indicates the key importance of recruitment and selection in successful people management and leadership. An awareness of issues and concepts within this area is an important tool for all those involved with leading, managing and developing people – even if they are not human resource managers per se. A recognition of the importance of this aspect of people management is not new, and ‘success’ in this field has often been linked with the avoidance of critical failure factors including undesirable levels of staff turnover and claims of discrimination from unsuccessful job applicants.

It has been argued here that it is also possible to identify aspects of recruitment and selection which link with critical success factors in the 21st century context, differentiating organisational performance and going some way to delivering employees who can act as ‘thinking performers’. It is proposed, for example, that a competencies approach focusing on abilities needed to perform a job well may be preferable to the use of a more traditional matching of job and person specifications. In addition, many organisations may increasingly wish to identify qualities of flexibility and creative thinking among potential employees, although this may not always be the case; many contemporary jobs do not require such competencies on the part of jobholders. It is also the case that organisations should be preoccupied with the question of validity of selection methods, ideally combining methods which are strong on practicality and cost, such as interviewing, with other measures which are more effective predictors of performance. It is maintained, finally; that a managing diversity approach, welcoming individual difference, may enhance organisational performance and create a climate in which thinking performers can emerge and flourish.

However, it is maintained that a contingency approach to recruitment and selection, recognising that organisational policies and practices are shaped by contextual factors, remains valid, and that ‘effectiveness’ in recruitment and selection may vary according to particular situational factors. In this regard it is noted that cultural differences could be an important factor in predicting the relative success of recruitment and selection measures.

Key Learning Points

- Managers involved in the recruitment and selection of workers have a key ‘gatekeeper’ role in giving or denying access to work.

- Effective recruitment and selection is characterised by a knowledge of social science topics such as perception.

- A stage logical approach to recruitment and selection, seeing it as a process, is recommended.

- We should examine the validity of different selection methods.

- Fairness is a fundamentally important principle reflecting the ethnically loaded nature of activity.

Review Questions

- Indicate with examples three ways in which recruitment and selection policies and practices can be used by an organisation aiming to develop staff as part of a talent management strategy.

- Evaluate the evidence regarding the potential validity of biodata and personality assessment as tools for selecting employees.

- What do you understand by the contingency approach to recruitment and selection? Provide two examples, from academic sources or your own experience, to illustrate this approach.

Explore Further

- Gilmore, S. and Williams, S. (2009) Human Resource Management. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Chapter 5 takes a themed approach to the topic of employee selection.

- Thompson, P. and McHugh, D. (2009) Work Organisations: A critical approach, 4th ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. In Chapter 19 entitled ‘Masks for Tasks’, the authors take a critical perspective on the topics of how we assess others’ attributes and how such perceptions are used in employee selection.

- Arnold, J. et al (2005) Work Psychology: Understanding human behaviour in the workplace 4th ed. Harlow: FT Prentice Hall. Chapter 5 provides a clear and interesting discussion of different selection techniques and their validity.

NSW Government. (n.d.). Workplace Policies and Procedures. https://www.industrialrelations.nsw.gov.au/employers/nsw-employer-best-practice/workplace-policies-and-procedures-checklist/

Benefits of having workplace policies

Well-written workplace policies:

- are consistent with the values of the organisation

- comply with employment and other associated legislation

- demonstrate that the organisation is being operated in an efficient and businesslike manner

- ensure uniformity and consistency in decision-making and operational procedures

- add strength to the position of staff when possible legal actions arise

- save time when a new problem can be handled quickly and effectively through an existing policy

- foster stability and continuity

- maintain the direction of the organisation even during periods of change

- provide the framework for business planning

- assist in assessing performance and establishing accountability

- clarify functions and responsibilities.

Developing and introducing workplace policies

Step 1 – Management Support

It is crucial to have senior management support for the implementation or modification of a policy, especially where policies relate to employee behaviour. The endorsement and modelling of the behaviour by senior managers and supervisors will encourage staff to take the policies seriously. While management support for a policy is an important first step before actively seeking employee feedback on a proposed policy, the idea for the policy and some of its details may in fact come from staff.

Step 2 - Consult with staff

Involve staff in developing and implementing workplace policies to promote stronger awareness, understanding and ownership of the outcome. Staff involvement also helps to determine how and when the policies might apply, and can assist in identifying possible unintentional outcomes of the policy.

Step 3 - Define the terms of the policy

Be explicit. Define key terms used in the policy at the beginning so that employees understand what is meant. The policy should explain what is acceptable and unacceptable behaviour in the workplace. You may wish to include specific examples to illustrate problem areas or unacceptable types of behaviours. For example:

An individual shall be deemed to be under the influence of alcohol if he/she exceeds a blood alcohol level of 0.05% (0.02% for heavy vehicle drivers).

Be clear about who the policy applies to. For example, does it only apply to employees of the company or to contractors and sub-contractors engaged to perform work on business premises? This is particularly important, for example, with occupational health and safety which covers everyone in the workplace.

The policy may also need to contain information about what to do if it is not possible to follow the policy. For example, if you have a policy relating to punctuality, you may need to include a procedure outlining what to do if the employee is going to be late.

The policy should also contain procedures to support the policy in its operation, such as the implications for not complying with the policy.

Example 1: Occupational health and safety

No employee is to commence work, or return to work while under the influence of alcohol or drugs. A breach of this policy is grounds for disciplinary action, up to and including termination of employment.

Example 2: Email policy

Using the organisation's computer resources to seek out, access or send any material of an offensive, obscene or defamatory nature is prohibited and may result in disciplinary action.

Step 4 - Put the policies in writing and publicise them

To be effective, policies need to be publicised and provided to all existing and new employees. This includes casual, part-time and full-time employees and those on maternity leave or career breaks.

Policies should be written in plain English and easily understood by all employees. Consider translating the policies into the appropriate languages for employees whose first language is not English.

Ensure all staff understand what the policies mean. Explain how to comply with the policies and the implications of not complying.

Step 5 - Training and regular referral

The policies may be explained to staff through information and/or training sessions, at staff meetings and during induction sessions for new staff. They should also be reiterated and discussed with staff regularly at staff meetings to ensure they remain relevant.

Copies of policies should be easily accessible. Copies may be kept in folders in a central location or staff areas, in staff manuals and available on the organisation's intranet system.

Step 6 – Implementation

It is important that policies are applied consistently throughout the organisation. A breach of a policy should be dealt with promptly and according to the procedures set out in the policy. The consequence of the breach should also suit the severity of the breach – whether it be a warning, disciplinary action or dismissal.

Case Study

An organisation which dismissed an employee for sexual harassment was subsequently ordered to re-employ the sacked staff member as they had failed to follow their own policy. The company had a policy of zero tolerance to sexual harassment but failed to exercise the provision when the policy was breached. The Commission hearing revealed that the company had breached its own policy when it issued the employee numerous unofficial warnings instead.

Step 7 - Evaluate and review

Review policies regularly to ensure they are current and in line with any changes within the organisation. Where policies are significantly changed they should be re-issued to all staff and the changes explained to them to ensure they understand the organisation's new directions. These changes should also be widely publicised.

Policy checklist

A workplace policy should:

- set out the aim of the policy

- explain why the policy was developed

- list who the policy applies to

- set out what is acceptable or unacceptable behaviour

- set out the consequences of not complying with the policy

- provide a date when the policy was developed or updated.

Policies also need to be reviewed on a regular basis and updated where necessary. For example, if there is a change in equipment or workplace procedures you may need to amend your current policy or develop a new one.

Employment law changes, changes to your award or agreement may also require a review of your policies and procedures. Stay up to date with relevant changes by regularly checking Fair Work Online [Fair Work Ombudsman]

Types of workplace policies

Here are some examples of common workplace policies that could assist your workplace:

- code of conduct

- recruitment policy

- internet and email policy

- mobile phone policy

- non-smoking policy

- drug and alcohol policy

- health and safety policy

- anti-discrimination and harassment policy

- grievance handling policy

- discipline and termination policy

- using social media.

Australian Human Resource Institute. (2015). Recruitment and Selection. https://www.ahri.com.au/assist/recruitment-and-selection/INFO-SHEET-Candidate-selection-decision-and-offer.pdf

The selection decision should be based on objective information gathered from the candidate’s application, any interviews and testing conducted as well as any reference and/or background checks

Candidate Selection, Decision and Offer

The selection decision

Once the selection processes are complete it is advisable to move quickly on the selection decision. Lengthy processes can result in candidates accepting other roles or losing interest in the role you are recruiting for.

There are two approaches that can be taken in making the final selection decision. You can reserve the decision until all selection processes are complete and look at each candidate’s performance and assessment in each of the processes. Alternatively, you can take a cumulative approach where decision are made at the completion of each individual selection process, gradually narrowing down the pool of candidates and selecting who to appoint from those who have survived all of the selection processes.

The selection decision should be based on objective information gathered from the candidate’s application, the interviews, any testing conducted and reference and background checks. The candidate that best addresses the selection criteria should be offered the position.

It is important to make the selection decision as soon as possible after the selection process has been completed. Do not allow the decision making process to drag out as, in a strong job market, high quality candidates may be in a position where they have more than one role offered to them.

The job offer

The initial job offer should be verbal and must be followed immediately by written confirmation of the job offer and the proposed terms of employment i.e. position title, salary, commencement date, any terms or conditions particular to the position. A full employment contract should then follow. For more information on how to develop contracts, please see our contract builder, in the Contracts section.

Unsuccessful candidates

All candidates for the role should be informed of the outcome of their application regardless of the stage in the selection process they reached. Any candidates who were spoken to on the phone or who attended an interview should be advised by phone so that feedback can be provided verbally. All other applicants can be e-mailed with a covering statement regarding the calibre of the candidates and details of the selection process undertaken.

For example:

“Thank you for your application for the receptionist role. A large number of high calibre applications were received for this position. The successful candidate was selected due to their extensive experience in similar roles within the industry. Thank you for taking the time to apply and we wish you well in your job search.”

Do not inform other preferred candidates that they have been unsuccessful in obtaining the role until the first preferred candidate has accepted the job offer. If the first preferred candidate does not accept the job offer, then the selectors can still consider other preferred candidates for the position.

Queensland Government. (2022). HR Policies and Procedures. https://www.business.qld.gov.au/running-business/employing/high-performing-workplaces/policies-procedures#developing-hr-policies-and-procedures

Developing HR policies and procedures

Policies and procedures should be lawful and reasonable directions from you to your employees. Remember to tailor the policies and procedures to your workplace. This will ensure you and your business are better protected.

Develop a policy in 5 steps

- Identify the need—what is the policy addressing?

- Gather information—read about the legal responsibilities relating to the topic and search online for free templates or examples

- Draft the policy—it should consider everyone who will use the policy and be

- Clear

- Concise

- Specific

- Simple enough for all involved to understand.

- Consult with employees—give employees the opportunity to consider and discuss the implications of the policy and to give their feedback.

- Review and finalise.

The most important HR policies

Where relevant, develop and implement policies to cover the following aspects of employment:

- Conduct (see guidelines below)

- Equal employment opportunity, discrimination, bullying and harassment

- Alcohol and other drugs

- Workplace health and safety

- Grievances or complaints

- Internet and email use

- Leave, including parental leave

- Performance counselling and discipline

- Privacy

- Social media (see our social media workplace guidelines template)

- Use of motor vehicles

- Working from home/telecommuting.

Establishing a code of conduct

A code of conduct is an important HR policy that outlines the standards of behaviour expected by your business of every employee. The code of conduct should be written down to give clear instructions about what employees can and can't do in the workplace.

Common topics to cover in a code of conduct include:

- Ethical principles—includes guidelines for appropriate and respectful workplace behaviour

- Values—refers to what is held as important, for example, an honest, fair and inclusive work environment

- Accountability—focuses on taking responsibility for one's actions, using information appropriately, being diligent, meeting duty-of-care obligations and avoiding conflicts of interest

- Standard of conduct—includes complying with the job description, commitment to the organisation and acceptable computer, internet and email usage

- Standard of practice—includes current policies and procedures and business operational manual

- Disciplinary actions—includes complaints handling and specific penalties for any violation of the code.

Customise the topics in your code of conduct for your business. When writing or reviewing your code of conduct, remember to consult with your employees and stakeholders for their input.

Department of Human Services. (n.d.).Equal Employment Opportunity Policy. https://dhs.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/word_doc/0008/147824/Equal-Employment-Opportunity-policy.doc

| Equal Employment Opportunity Policy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Policy Number | <Insert Number> | Version | <Insert Name> |

| Drafted By | <Insert Name> | Approved by Board on | <Insert Date> |

| Responsible Person | <Insert Name> | Scheduled Review Date | <Insert Date> |

Introduction

[Name of Organisation] recognises that Equal Employment Opportunity is a matter of employment obligation, social justice and legal responsibility. It also recognises that prohibiting discriminatory policies and procedures is sound management practice.

This policy has been designed to facilitate the creation of a workplace culture that maximises organisational performance through employment decisions. These decisions will be based on real business needs without regard to non-relevant criteria or distinctions, and will ensure that all decisions relating to employment issues are based on merit.

Purpose

This policy is designed to ensure that [Name of Organisation] complies with all of its obligations under the relevant legislation.

Definitions

Discrimination consists of treating an individual with a particular attribute less favourably than an individual without that attribute or with a different attribute under similar circumstances. It can also involve seeking to impose a condition or requirement on a person with an attribute who does not or cannot comply, while people without that attribute do or can comply.

Equal Employment Opportunity consists of ensuring that all employees are given equal access to training, promotion, appointment or any other employment related issue without regard to any factor not related to their competency and ability to perform their duties.

Victimisation happens where an employee is treated harshly or subjected to any detriment because they have made a complaint of discrimination or harassment. Victimisation will also happen if a person is subjected to a detriment because they have furnished any information or evidence in connection with a discrimination complaint.

Policy