Reading A: The Impact of Unconscious Bias in Healthcare: How to Recognise and Mitigate it

Reading B: Key Components of Shared Decision Making Models: A Systematic Review.

Reading C: Cultural Competence Dimensions and Outcomes: A Systematic Review of the Literature

Reading D: Experiences that Inspire Hope: Perspectives of Suicidal Patients

Reading E: The importance of critical incident reporting – and how to do it

Important note to students:

The Readings contained in this section of the module are a collection of extracts from various books, articles and other publications. The Readings have been replicated exactly from their original source, meaning that any errors in the original document will be transferred into the Readings. In addition, if a Reading originates from an American source, it will maintain its American spelling and terminology. IAH is committed to providing you with high quality study materials and trusts that you will find these Readings beneficial and enjoyable.

Marcelin, J. R., Siraj, D. S., Victor, R., Kotadia, S., & Maldonado, Y. A. (2019). The impact of unconscious bias in healthcare: How to recognise and mitigate it. The Journal of Infectious Disease, 220(S2), S62–S73. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiz214

There is compelling evidence that increasing diversity in the healthcare workforce improves healthcare delivery, especially to underrepresented segments of the population. Although we are familiar with the term “underrepresented minority” (URM), the Association of American Medical Colleges, has coined a similar term, which can be interchangeable: “Underrepresented in medicine means those racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population”. However, this definition does not include other non-racial or ethnic groups that may be underrepresented in medicine, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning/queer (LGBTQ) individuals or persons with disabilities. US census data estimate that the prevalence of African American and Hispanic individuals in the US population is 13% and 18%, respectively, while the prevalence of Americans identifying as LGBT was estimated by Gallup in 2017 to be about 4.5%. Yet African American and Hispanic physicians account for a mere 6% and 5%, respectively, of medical school graduates, and account for 3% and 4%, respectively, of full-time medical school faculty. As for LGBTQ medical graduates, the Association of American Medical Colleges does not report their prevalence. Persons with disabilities are estimated to be 8.7% of the general population, while the prevalence of physicians with disabilities has been estimated to be a mere 2.7%. Furthermore, although women currently outnumber men in first-year medical school classes, gender disparities still exist at higher ranks in women’s medical careers.

Unconscious or implicit bias describes associations or attitudes that reflexively alter our perceptions, thereby affecting behavior, interactions, and decision-making. The Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) notes that bias, stereotyping, and prejudice may play an important role in persisting healthcare disparities and that addressing these issues should include recruiting more medical professionals from underrepresented communities. Bias may unconsciously influence the way information about an individual is processed, leading to unintended disparities that have real consequences in medical school admissions, patient care, faculty hiring, promotion, and opportunities for growth. Compared with heterosexual peers, LGBT populations experience disparities in physical and mental health outcomes. Stigma and bias (both conscious and unconscious) projected by medical professionals toward the LGBTQ population play a major role in perpetuating these disparities. Interventions on how to mitigate this bias that draw roots from race/ethnicity or gender bias literature can also be applied to bias toward gender/sexual minorities and other underrepresented groups in medicine.

The specialty of infectious diseases is not free from disparities. Of >11 000 members of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), 41% identify as women, 4% identify as African American, 8% identify as Hispanic, and <1% identify as Native American or Pacific Islander (personal communication, Chris Busky, IDSA chief executive officer, 2019). However, IDSA data on members who identify as LGBTQ and members with disabilities are not available.

The 2017 IDSA annual compensation survey reports that women earn a lower income than men, and a review of the full report demonstrates similar disparities among URM physicians, compared with their white peers. While it may not be feasible to assign a direct causal relationship between unconscious bias and disparities within the infectious diseases specialty, it is reasonable and ethical to attempt to address any potential relationship between the two. In this article, we define unconscious bias and describe its effect on healthcare professionals. We also provide strategies to identify and mitigate unconscious bias at an organizational and individual level, which can be applied in both academic and non-academic settings.

Unconscious Bias – The Role it Plays and How to Measure it

Even in 2019, overt racism, misogyny, and transphobia/homophobia continue to influence current events. However, in the decades since the healthcare community has moved toward becoming more egalitarian, overt discrimination in medicine based on gender, race, ethnicity, or other factors have become less conspicuous. Nevertheless, unconscious bias still influences all human interactions. The ability to rapidly categorize every person or thing we encounter is thought to be an evolutionary development to ensure survival; early ancestors needed to decide quickly whether a person, animal, or situation they encountered was likely to be friendly or dangerous. Centuries later, these innate tendencies to categorize everything we encounter is a shortcut that our brains still use.

Stereotypes also inadvertently play a significant role in medical education. Presentation of patients and clinical vignettes often begin with a patient’s age, presumed gender, and presumed racial identity. Automatic associations and mnemonics help medical students remember that, on examination, a black child with bone pain may have sickle-cell disease or a white child with recurrent respiratory infections may have cystic fibrosis. These learning associations may be based on true prevalence rates but may not apply to individual patients. Using stereotypes in this fashion may lead to premature closure and missed diagnoses, when clinicians fail to see their patients as more than their perceived demographic characteristics. In the beginning of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, the high prevalence of HIV among gay men led to initial beliefs that the disease could not be transmitted beyond the gay community. This association hampered the recognition of the disease in women, children, heterosexual men, and blood donor recipients. Furthermore, the fact that white gay men were overrepresented in early reported prevalence data likely led to lack of recognition of the epidemic in communities of color, a fact that is crucial to the demographic characteristics of today’s epidemic. Today, there is still no clear solution to learning about the epidemiology of diseases without these imprecise associations, which can impact the rapidity of accurate diagnosis and therapy.

Impact of Bias on Healthcare Delivery

Unconscious bias describes associations or attitudes that unknowingly alter one’s perceptions and therefore often go unrecognized by the individual, whereas conscious bias is an explicit form of bias that is based on one’s discriminatory beliefs and values and can be targeted in nature. While neither form of bias belongs in the healthcare profession, conscious bias actively goes against the very ethos of medical professionals to serve all human beings regardless of identity. Conscious bias has manifested itself in severe forms of abuse within the medical profession. One notable historical example being the Tuskegee syphilis study, in which black men were targeted to determine the effects of untreated, latent syphilis. The Tuskegee study demonstrated how conscious bias, in this case manifested in the form of racism, led to the unethical treatment of black men that continues to have long-lasting effects on health equity and justice in today’s society. Given the intentional nature of conscious bias, a different set of tools and a greater length of time are likely required to change one’s attitudes and actions. Tackling unconscious bias involves willingness to alter one’s behaviors regardless of intent, when the impact of one’s biases are uncovered and addressed.

There is still debate, however, about the degree to which unconscious bias affects clinician decision-making. In one systematic review on the impact of unconscious bias on healthcare delivery, there was strong evidence demonstrating the prevalence of unconscious bias (encompassing race/ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, age, weight, persons living with HIV, disability, and persons who inject drugs) affecting clinical judgment and the behavior of physicians and nurses toward patients. However, another systematic review found only moderate-quality evidence that unconscious racial bias affects clinical decision-making. A detailed discussion of the impact of unconscious bias on healthcare delivery is out of the scope of this article, which is focused on the impact of unconscious bias as it relates to healthcare professionals themselves. Nevertheless, strategies to mitigate the effects of unconscious bias (discussed later) can be applied to healthcare delivery and patient interactions.

Measuring Bias – The Implicit Association Test

While we know that unconscious bias is ubiquitous, it can be difficult to know how much it affects a person’s daily interactions. In many cases, an individual’s unconscious beliefs may differ from their explicit actions. For example, healthcare professionals, if asked, might say they try to treat all patients equally and may not believe they hold negative attitudes about patients. However, by definition, they may lack awareness of their own potential unconscious biases, and their actions may unknowingly suggest that these biases are active.

To measure unconscious bias, Drs Mahzarin Banaji and Anthony Greenwald developed the IAT in 1998. Many versions of the IAT are accessible online (available at: https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/), but one of the most studied is the Race IAT. The IAT has been extensively studied as an inexpensive tool that provides feedback on an individual biases for self-reflection. The IAT calculates how quickly people associate different terms with each other. To determine unconscious race bias, the race IAT asks the subject to sort pictures (of white and black people) and words (good or bad) into pairs. For example, in one part of the Race IAT, participants must associate good words with white people and bad words with black people. In another part of the Race IAT, they must associate good words with black people and bad words with white people. Based on the reaction times needed to perform these tasks, the software calculates a bias score. Category pairs that are unconsciously preferred are easier to sort (and therefore take less time) than those that are not. These unconscious associations can be identified even in individuals who outwardly express egalitarian beliefs. According to Project Implicit, the Race IAT has been taken >4 million times between 2002 and 2017, and 75% of test takers demonstrate an automatic white preference, meaning that most people (including a small group of black people) automatically associate white people with goodness and black people with badness. Proponents of the IAT state that automatic preference for one group over another can signal potential discriminatory behavior even when the individuals with the automatic preference outwardly express egalitarian beliefs. These preferences do not necessarily mean that an individual is prejudiced, which is associated with outward expressions of negative attitudes toward different social groups.

Many of the studies of unconscious bias described in this article use the IAT as the primary tool for measuring the phenomenon. Nevertheless, the degree to which the IAT predicts behavior is as of yet unclear, and it is important to recognize the limitations and criticisms of the IAT, as this is pertinent to its potential application in mitigating unconscious bias. Blanton et al reanalyzed data from 2 studies supporting the validity of the IAT, claiming that there is no evidence predicting individual behavior, with concerns for interjudge reliability and inclusion of outliers affecting results. Response to this criticism by McConnell et al describes extensive training of test judges and evidence that the reanalysis was not a perfect replication of methods. Blanton et al argue further in a different article that attempting to explain behavior on the basis of results of the IAT is problematic because the test relies on an arbitrary metric, leading to identified preferences when individuals are “behaviorally neutral”. Notwithstanding the limitations of the IAT, none of its critics refute the existence of unconscious bias and that it can influence life experiences. The following sections review how unconscious bias affects different groups in the healthcare workforce.

Racial Bias

Medical school admissions committees serve as an important gatekeeper to address the significant disparities between racial and ethnic minorities in healthcare as compared to the general population. Yet one study demonstrated that members of a medical school admissions committee displayed significant unconscious white preference (especially among men and faculty members) despite acknowledging almost zero explicit white preference. An earlier study of unconscious racial and social bias in medical students found unconscious white and upper-class preference on the IAT but no obvious unconscious preferences in students’ response to vignette-based patient assessments. Unconscious bias affects the lived experiences of trainees, can potentially influence decisions to pursue certain specialties, and may lead to isolation. A recent study by Osseo-Asare et al described African American residents’ experiences of being only “one of a few” minority physicians; some major themes included discrimination, the presence of daily microaggressions, and the burden of being tasked as race/ethnic “ambassadors,” expected to speak on behalf of their demographic group.

Gender Bias

Gender bias in medical education and leadership development has been well documented. Medical student evaluations vary depending on the gender of the student and even the evaluator. Similar studies have demonstrated gender bias in qualitative evaluations of residents and letters of recommendations, with a more positive tone and use of agentic descriptors in evaluations of male residents as compared to female residents. Studies evaluating inclusion of women as speakers have also demonstrated gender bias, with fewer women invited to speak at grand rounds and differences in the formal introductions of female speakers as compared to male speakers, with men more likely referred to by their official titles than women.

Sexual and Gender Minority Bias

Sexual and gender minority groups are underrepresented in medicine and experience bias and microaggressions similar to those experience by racial and ethnic minorities. Experiences with or perceptions of bias lead to junior physicians not disclosing their sexual identity on the personal statement part of their residency applications for fear of application rejection or not disclosing that they are gay to colleagues and supervisors for fear of rejection or poor evaluations. In one study, some physician survey respondents indicated some level of discomfort about people who are gay, transgender, or living with HIV being admitted to medical school. These respondents were less likely to refer patients to physician colleagues who were gay, transgender, or living with HIV. These explicit biases were significantly reduced, compared with those revealed in prior surveys done in 1982 and 1999; opposition to gay medical school applicants went from 30% in 1982 to 0.4% in 2017, and discomfort with referring patients to gay physicians went from 46% in 1982 to 2% in 2017. The 2017 survey did not measure levels of unconscious bias, which is likely to still be pervasive despite decreased explicit bias. As with other types of bias, these data reveal that explicit bias against gay physicians has decreased over time; the degree of unconscious bias, however, likely persists. While this is encouraging to some degree, unconscious bias may be much more challenging to confront than explicit bias. Thus, members of underrepresented groups may be left wondering about the intentions of others and being labeled as “too sensitive.”

Studies including the perspectives of LGBTQ healthcare professionals demonstrate that major challenges to their academic careers persist to this day. These include lack of LGBTQ mentorship, poor recognition of scholarship opportunities, and noninclusive or even hostile institutional climates. Phelan et al studied changes in biased attitudes toward sexual and gender minorities during medical school and found that reduced unconscious and explicit bias was associated with more-frequent and favorable interactions with LGBTQ students, faculty, residents, and patients.

Disability Bias

Physicians with disabilities constitute another minority group that may experience bias in medicine, and the degree to which they experience this may vary, depending on whether disabilities may be visible or invisible. One study estimated the prevalence of self-disclosed disability in US medical students to be 2.7%. Medical schools are charged with complying with the Americans With Disabilities Act, but only a minority of schools support the full spectrum of accommodations for students with disabilities. Many schools do not include a specific curriculum for disability awareness. Physicians with disabilities have felt compelled to work twice as hard as their able-bodied peers for acceptance, struggled with stigma and microaggressions, and encountered institutional climates where they generally felt like they did not belong. These are themes that are shared by individuals from racial and ethnic minorities.

Mitigating Unconscious Bias

A strategy to counter unconscious bias requires an intentional multidimensional approach and usually operates in tandem with strategies to increase diversity, inclusion, and equity. This is becoming increasingly important in training programs in the various specialties, including infectious diseases. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education recently updated their common program requirements for fellowship programs and has stipulated that, effective July 2019, “[t]he program’s annual evaluation must include an assessment of the program’s efforts to recruit and retain a diverse workforce”. The implication of this requirement is that recognition and mitigation of potential biases that may influence retention of a diverse workforce will ultimately be evaluated (directly or indirectly). Mitigating unconscious bias and improving inclusivity is a long-term goal requiring constant attention and repetition and a combination of general strategies that can have a positive influence across all groups of people affected by bias. These strategies can be implemented at organizational and individual levels and, in some cases, can overlap between the 2 domains. In this section, we review how infectious diseases clinicians and organizations like IDSA and hospitals can use some of these strategies to address and mitigate implicit bias in our specialty.

Organizational Strategies

Commitment to a Culture of Inclusion: More Than Just Diversity Training or Cultural Competency

Creating change requires more than just a climate survey, a vision statement, or creation of a diversity committee. Organizations must commit to a culture shift by building institutional capacity for change .This involves reaffirming the need not only for the recruitment of a critical mass of underrepresented individuals, but equally importantly, the recruitment of critical actor leaders who take the role of change agents and have the power to create equitable environments. These change agents need not themselves be underrepresented; indeed, the success of culture change requires the involvement of allies within the majority group (eg, men, white people, and cis-gender heterosexual individuals). IDSA has demonstrated a commitment to this type of culture change with recent changes in leadership structure and with intentional recruitment of individuals invested in diversity and inclusion; however, there is always room for reevaluation of other areas where diversity is desired.

Committing to a culture of inclusion at the academic-institution level involves creating a deliberate strategy for medical trainee admission and evaluation and faculty hiring, promotion, and retention. Capers et al describe strategies for achieving diversity through medical school admissions, many of which can also be applied to faculty hiring and promotion. Notable strategies they suggest include having admissions (or hiring) committee members take the IAT and reflect on their own potential biases before they review applications or interview candidates. They also recommend appointing women, minorities, and junior medical professionals (students or junior faculty) to admissions committees, emphasizing the importance of different perspectives and backgrounds. Organizations can also survey employee perception of inclusivity. These assessments include questions on the degree to which an individual feels a sense of belonging within an institution, alongside questions pertaining to experiences of bias on the grounds of cultural or demographic factors. Conducting regular assessments and analysis of survey results, particularly on how individuals of diverse backgrounds feel they can exist within the organization and their culture simultaneously, allows organizations to ensure that their trainings on unconscious bias and promotion of cultural humility lead to long-term positive change. Furthermore, realizing that different demographic groups may feel less respected than others provides information on areas of focus for consequent refresher seminars on combating unconscious bias in conjunction with cultural humility.

Meaningful Diversity Training and the Usefulness of the IAT

Notwithstanding potential criticisms of the IAT with respect to prediction of discriminatory behavior, this can be a useful tool within a comprehensive organizational training seminar directed toward understanding and addressing individual unconscious bias. In the study by Capers et al, over two thirds of admissions committee members who took the IAT and responded to the post-IAT survey felt positive about the potential value of this tool in reducing their unconscious bias. Additionally, almost half were cognizant of their IAT results when interviewing for the next admissions cycle, and 21% maintained that knowledge of this bias affected their decisions in the next admissions cycle. Perhaps this knowledge led to conscious changes in committee member behavior because, in the following year, the matriculating class was the most diverse in that institution’s history. A similar bias education intervention coupled with the IAT led to a decreased unconscious gender leadership bias in one academic center. IDSA and infectious diseases practices (or academic divisions) could consider ways to incorporate this into already established training for those in leadership roles or on leadership search committees.

Of course, the potential applicability of the IAT can be overstated—at best, several meta-analyses have demonstrated that there may only be a weak correlation between IAT scores and individual behavior, and several criticisms of the IAT have already been discussed here. Additionally, while important to acknowledge that bias is pervasive, care must be taken to avoid normalizing bias and stereotypes because this may have the unintended consequence of reinforcing them. Important points that should be emphasized when using the IAT as part of diversity training include that (1) people should be aware of their own biases and reflect on their behaviors individually; (2) the IAT can suggest generally how groups of people with certain results may behave, rather than how each individual will behave; and (3) on its own, the IAT is not a sufficient tool to mitigate the effects of bias, because if there is to be any chance of success, an active cultural/behavioral change must be engaged in tandem with bias awareness and diversity training.

Individual Strategies

Deliberative Reflection

Before encounters that are likely to be affected by bias (such as trainee evaluations, letters of recommendation, feedback, interviews, committee decisions, and patient encounters), deliberative reflection can help an individual recognize their own potential for bias and correct for this. It is also a good time to consider the perspective of the individual whom they will be evaluating or interacting with and the potential impact of their biases on that individual. Participants can be encouraged to evaluate how their own experiences and identities influence their interactions. Including data on lapses in proper care due to provider bias also proves helpful in giving workers real-life examples of the consequences of not being vigilant for bias. This motivated self-regulation based on reflections of individual biases has been shown to reduce stereotype activation and application. If one unintentionally behaves in a discriminatory manner, self-reflection and open discussion can help to repair relationships.

Question and Actively Counter Stereotypes

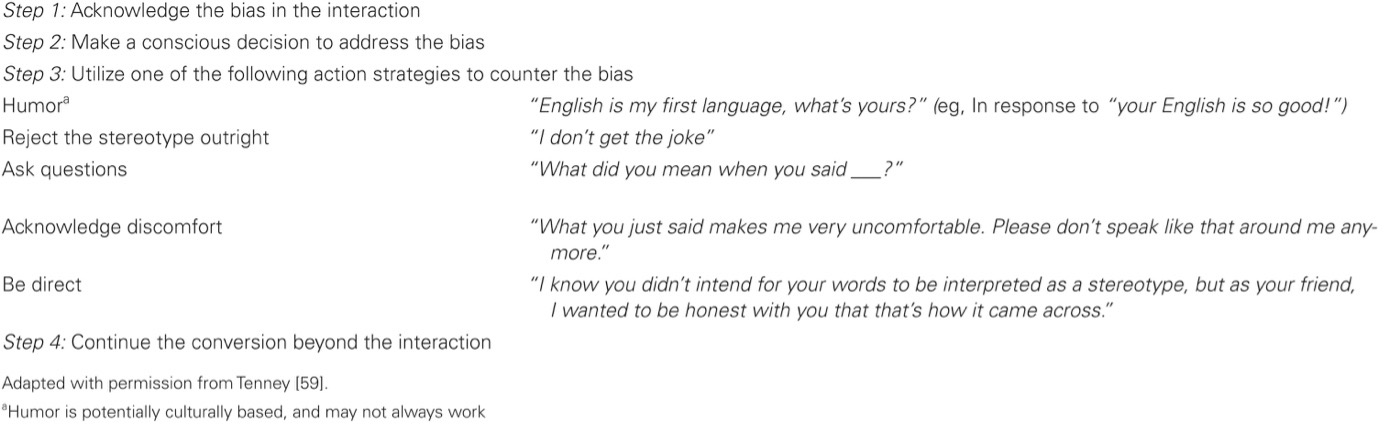

Individuals may question how they can actively counter stereotypes and bias in observed interactions. The active-bystander approach adapted from the Kirwan Institute can provide insight into appropriate responses in these situations.

Strategies That Apply to Both Organizations and Individuals

Cultural Competency and Beyond: Cultural Humility

Healthcare organizations seeking to develop providers who can work seamlessly with colleagues and more effectively treat patients from all cultural backgrounds have been conducting trainings in cultural competency. The term “cultural competency” implies that one has achieved a static goal of championing inclusivity. This approach imparts a false sense of confidence in leaders and healthcare professionals and fails to recognize that our understanding of cultural barriers is continually growing and evolving. Cultural humility has been proposed as an alternate approach, subsuming the teachings of cultural competency while steering participants toward a continuous path of discovery and respect during interactions with colleagues and patients of different cultural backgrounds. Other synonymous terms include “cultural sensitivity” and “cultural curiosity.” Rather than checking a box for training, cultural humility focuses on the individual and teaches that developing one’s self-awareness is a critical step in achieving mindfulness for others. Cultural humility emphasizes that individuals must acknowledge the experiential lens through which they view the world and that their view is not nearly as extensive, open, or dynamic as they might perceive. By training leaders and healthcare professionals that they do not need to be and ultimately cannot be experts in all the intersecting cultures that they encounter, healthcare professionals can focus on a readiness to learn that can translate to greater confidence and willingness in caring for patients of varying backgrounds.

As cultural humility is important to recognizing and mitigating conscious and unconscious biases, patient simulations and diversity-related trainings should be augmented with discussions about cultural humility. By integrating cultural humility into healthcare training procedures, organizations can strive to eliminate the perceived unease healthcare professionals might experience when interacting with individuals from backgrounds or cultures unfamiliar to them. Cultural humility starts from a condition of empathy and proceeds through the asking of open questions in each interaction. Instilling elements of cultural humility training within simulation-based learning provides participants with experience in treating a wide array of patients while providing low-risk, feedback-based learning opportunities.

Diversify Experiences to Provide Counterstereotypical Interactions

Exposing individuals to counterstereotypical experiences can have a positive impact on unconscious bias. Therefore, intentional efforts to include faculty from underrepresented groups as preceptors, educators, and invited speakers can help reduce the unconscious associations of these responsibilities as unattainable. Capers et al suggest that including students, women, and African Americans and other racial and ethnic minorities on admissions committees may be part of a strategy to reduce unconscious bias in medical school admissions. If institutions, organizations, and conference program committees are aware of their own metrics in this respect, following this information with deliberate choices to remedy inequities can have a profound impact on increasing diversity. Furthermore, in medical training, while deliberate curricula involving disparities and care of underrepresented individuals are beneficial, educators must be aware of the impact of the hidden curriculum on their trainees. The term “hidden curriculum” refers to the aspects of medicine that are learned by trainees outside the traditional classroom/didactic instruction environment. It encompasses observed interactions, behaviors, and experiences often driven by unconscious and explicit bias and institutional climate. Students can be taught to actively seek out the hidden curriculum in their training environment, reflect on the lessons, and use this reflection to inform their own behaviors. Individuals can intentionally diversify their own circles, connecting with people from different backgrounds and experiences. This can include the occasionally awkward and uncomfortable introductions at professional meetings or at community events, making an effort to read books by diverse authors, or trying new foods with a colleague. These are small behavioral changes that, with time, can help to retrain our brain to classify people as “same” instead of “other.”

Mentorship and Sponsorship

Mentors can, at any stage in one’s career, provide advice and career assistance with collaborations, but sponsors are typically more senior individuals who can curate high-profile opportunities to support a junior person, often with potential personal or professional risk if that person does not meet expectations. URMs and women physicians tend not to have as much support with mentoring and sponsorship as the majority group, white men. Qualitative studies of URM physician perspectives typically reveal themes of isolation and lack of mentorship, regardless of the URM group being studied. Possible reasons include lack of mentors from similar backgrounds or ineffective mentoring in discordant mentor-mentee relationships. Mentor-training workshops that intentionally include unconscious bias training can enhance the effectiveness of mentors working with diverse trainees and junior faculty and address this potential barrier to URM success. Providing mentorship within an individual department, as well as support for participating in external mentorship and career development programs, can help create sponsorship opportunities that eventually influence career advancement. Many professional societies such as IDSA provide mentorship opportunities, and these can be enhanced by encouraging more sponsorship of junior clinicians for opportunities such as podium lectures, moderating at conferences, writing editorials, or committee positions.

Summary

In the years since the IAT was first described, researchers have published countless data on the impact of unconscious bias. Fortunately, explicit and implicit attitudes toward many disenfranchised groups of people have regressed to a more neutral position over time, but this does not mean that unconscious bias has disappeared. Just as healthcare providers are required to stay up to date on medical techniques and procedures to best serve their patients, we propose that trainings involving the social aspects of medicine be treated similarly. Cultural humility is characterized by lifelong learning and is a key aspect of a successful provider-patient relationship. Thus, it is imperative that healthcare organizations and professional medical societies such as IDSA continually provide healthcare professionals with learning opportunities to enhance their interactions with individuals different from themselves. Effectively addressing unconscious bias and subsequent disparities in IDSA will need comprehensive, multifaceted, and evidence-based interventions.

Bomhof-Roordink, H., Gärtner, F. R., Stiggelbout, A. M., & Pieterse, A. H. (2019). Key components of shared decision making models: a systematic review. BMJ Open, 9(12). http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031763

Shared decision making (SDM) between patients and healthcare professionals is gradually becoming the norm across Western societies as the model for making patient-centred healthcare decisions and achieving value-based care. SDM is based on the thought that healthcare professionals are the experts on the medical evidence and patients are the experts on what matters most to them.3 Systematic reviews of published SDM-models date back to 2006 and 2007. Makoul and Clayman concluded that there is no unified SDM-model, and proposed a set of essential elements to form an integrative model of SDM (eg, Define and/or explain the problem, Discuss pros/cons, Patient values/preferences, Make or explicitly defer decision). From their perspective, elements can be initiated either by patients or healthcare professionals, and they purposively abstained from identifying actors in their model so as not to place sole responsibility on either. Soon after, a second systematic review concluded that the focus of SDM-models is placed on information exchange and on the involvement of both patient and healthcare professional in making the decision. Since then, SDM has gained attention exponentially, with new SDM-models emerging, and with what SDM specifically entails remaining under debate. Moreover, in a systematic review of measures to assess SDM we noted that developers of SDM measures often only vaguely define the SDM construct or do not define it at all. Meanwhile, there are calls to extend the conceptualization of SDM, such as by focusing on the person facing the decision rather than on a consultation, or by shifting the focus of SDM to relationship-centred care11 or to humanistic communication.

Clarity about what SDM constitutes in a specific situation is essential for training, implementation, policy, and research purposes. This systematic review aims to (1) provide an up-to-date overview of SDM-models, (2) give insight in the prominence of components present in SDM-models, (3) describe who is identified as responsible within the components (ie, patient, healthcare professional, both or none), (4) show the occurrence of SDM-components over time, and (5) present an SDM-map to identify SDM-components seen as key, per healthcare setting.

Methods

In the following we use the term model for both models and definitions, for sake of readability. These terms may have a slightly different meaning but are often used interchangeably. No ethical approval was required. We registered this systematic review at PROSPERO: CRD42015019740.

Search strategy

Seven electronic databases (Academic Search Premier, Cochrane, Embase, Emcare, PsycINFO PubMed, and Web of Science) were systematically searched for articles published from inception up to and including September 2, 2019. The search terms “shared decision” and related terms such as “shared medical decision”, “shared treatment decision” and “shared clinical decision”, and their plural forms, as well as the broadly used abbreviation SDM were used to search in title and keywords. The search was restricted to peer-reviewed scientific articles; to publications in English for pragmatic reasons; and to publications about humans.

Eligibility criteria

During the screening of titles and abstracts we determined whether the term model or definition was used, and if not, whether it could be expected that the authors would provide a new or adapted SDM-model. Full-text articles were excluded if they were not externally peer-reviewed or not written in English. Full-text articles were included if the authors explicitly described a new model of the SDM-process between a patient and one or more healthcare professionals, or if the authors had adapted an existing model based on own insights or research outcomes, and if the model was described comprehensibly, that is, in enough detail to explain the process. We therefore excluded articles in which the authors only referred to a model described elsewhere, only mentioned the concept of SDM, or explained it briefly only. Also, the focus was on models that assumed a competent patient, that is, a patient that was able to participate in the decision making process.

Selection process

Three researchers (AP, HB-R, FG) independently reviewed titles and abstracts of the first 100 records and discussed inconsistencies until consensus was obtained. Then, in pairs, the researchers independently screened titles and abstracts of all articles retrieved. In case of disagreement, consensus on which articles to screen full-text was reached by discussion. If necessary, the third researcher was consulted to make the final decision. Next, two researchers (AP, HB-R) independently screened full-text articles for inclusion. Again, in case of disagreement, consensus was reached on inclusion or exclusion by discussion and if necessary, the third researcher (FG) was consulted.

Data extraction

We extracted the description of each SDM-model (ie, the verbatim text describing the model) as well as the following general characteristics: first author, year of publication, healthcare setting, and development process (ie, informed by existing literature or by data collected with the purpose to inform the model; for the latter, we extracted methods and respondents). Using a standardised extraction form, one researcher (AP or HB-R) extracted the data, the other researcher verified it, and inconsistencies were discussed until consensus was reached.

Data analysis

We separated each SDM-model description into text fragments, that is, the smallest piece of text conveying a single constituent of the model, often delineated by conjunctions or punctuation. We then first classified all text fragments using elements, starting out with the list of 32 elements that Makoul and Clayman reported. We refined or split elements, or added new elements if necessary. Elements may describe specific behaviours (eg, List options) but need not (eg, Patient values). Second, we determined the actor for each classified text fragment. An actor was defined as the person identified to be responsible for the occurrence of the behaviour or result described in the text fragment (ie, no actor identified, patient and healthcare professional, only patient, or only healthcare professional). To illustrate, for Patient values it may be stated in the text fragment that healthcare professionals need to ask about patients’ values, or that patients need to express their values. In the first case, the actor would be the healthcare professional; in the second, the patient. Note that the actor identified for the same element that is present in different SDM-models may differ between models, depending on the actor identified by the authors of the respective models. Third, we clustered elements representing a shared theme into overarching components taking into account the underlying text fragments, and formulated a name for each component, for example, Provide neutral information, or Advocate patient views. Clustering of elements into components was based on the content of the elements and regardless of actor. For the ensuing components, we now again determined the actor(s), based on the actors identified for the constituting elements. For each analysis step, one researcher (HB-R or AP) performed the analysis, the other verified it, and inconsistencies were discussed until consensus was reached. To depict a possible trend in the occurrence of components in SDM-models over time, we grouped the SDM-models by publication date into four different time periods (ie, until 2010, 2010–2014, 2015–2017, since 2018), each containing approximately the same number of models. We calculated in how many of the models during a particular time period each component was present, as a percentage.

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document.

Results

The search yielded 4164 unique records. Forty articles were included in this review, from 34 different first authors, each describing a unique model. The articles were published from 1997 up to and including September 2, 2019.

Discussion

Our review provides an inventory of the 40 SDM-models currently available. Many models defining SDM are of relatively recent date: half of the models included were published in 2015 or later. Similarities between models exist but significant heterogeneity still remains, as others have noted before.5 This may not be surprising considering the fact that almost half of the models have been developed for a variety of decisions relating to screening, diagnostic testing or treatment decisions, and that 28 of the non-generic models have been developed for 13 different healthcare settings.

Over a decade ago, Makoul and Clayman noted the low frequency with which authors defining SDM recognised and cited previous work in the field; they found one-third of articles with a conceptual model failed to cite any other model. Our review shows that authors at least referred to existing literature about SDM, also when they did not base their own model on an earlier SDM-model. Moreover, especially the relatively older models that Charles, Towle, Elwyn, and Makoul and their colleagues have developed have each informed at least six other SDM-models. These authors therefore have had a significant impact on thinking about what constitutes an SDM-process. They and others have further published adapted versions of their own models. Components specific to these models are therefore prominently present in our SDM-map. Further and remarkably, views of patients and/or healthcare professionals, the ones who enact SDM in clinical practice, were only assessed to inform fourteen of the 40 models. This may have resulted in underrepresentation of components that patients and healthcare professionals consider to be indispensable in current thinking about what constitutes SDM.

As may be expected, the component Describe treatment options was present in the vast majority of models. The transfer of information about treatment options is clearly key to SDM, and patients need this information to be able to participate in SDM. However, conveying treatment information to patients in itself does not safeguard that patients are actually able to participate. For the component Reach mutual agreement, two ways of framing appeared: mutual agreement about the final decision is a requisite in part of the models, while in others this requirement is not formulated explicitly, or specifically relates to the process required to reach a decision rather than to the final decision itself. It may be of minor importance who makes the final call or whether all parties involved fully agree that the option chosen is the best possible option for this patient in this situation, as long as the process is shared. Patient expertise and Healthcare professional expertise were rarely present in SDM-models. Since the first is often mentioned as the rationale for SDM, it may not be surprising that it is not part of the definition of SDM. The authors’ focus may be more on how to uncover this expertise (eg, Learn about the patient) when describing the SDM process than on the expertise itself.

Creating choice awareness clearly caught attention since 2010. Choice awareness has been defined as “acknowledging that the patient’s situation is mutable and that there is more than one sensible way to address or change this situation”, and been put forward as pivotal in achieving SDM for some time. However, despite the inclusion of this behaviour in models, it is seldom seen in clinical practice. Both Provide a recommendation and Healthcare professional preferences are less and less present in SDM-models, suggesting that authors ideally see that healthcare professionals’ preferences influence patients as little as possible. One may question if this is ideal from patients’ perspective, as patients may consider receiving a treatment recommendation part of SDM. Importantly, providing a recommendation that integrates informed patient preferences may indeed help patients in deciding what option they would prefer, and perfectly fits with SDM. Our results further show that the calls that were recently made to extend the conceptualization of SDM, such as by focusing on the person facing the decision rather than on a consultation, or by explicitly including time outside of consultations would indeed add new aspects to the conceptualizations of SDM so far. Offer time and Gather support and information for example, are part of relatively few models and typically convey attention to time outside of consultations and to the involvement of other stakeholders in the process, such as informal caregivers. Future SDM-models may use a triadic approach towards SDM, in which the role of the caregiver is made explicit.

It is noteworthy that in one-fourth of the models overall, only the healthcare professional is identified as the actor in SDM, that is, is seen as responsible for the occurrence of an SDM-process. This does not align with the formal acknowledgement in 2011 of patients’ role in making SDM happen in the Salzburg statement on SDM. It bears the question whether it is justified to put the onus of achieving SDM on healthcare professionals only, and how patients can truly participate in an SDM-process if they are not recognised as active participants. It is especially important to acknowledge patients’ role in SDM-models since patients formulate their own responsibilities in SDM, in qualitative studies asking about SDM. Authors of SDM-models should therefore carefully consider patients’ role in SDM. Also, we recommend that authors who develop an SDM-model clarify each actor’s role. Doing so will help elucidate whose behaviour(s) should be targeted when aiming to improve SDM-levels, or measured when aiming to evaluate SDM-levels. This will facilitate the development of appropriate interventions and of valid measurement instruments. Also, authors of future SDM-models may want to involve patients and healthcare professionals in the development process of their models, to ensure that these reflect the views of those who enact SDM in practice.

This study provides a systematic overview of SDM-models published so far. A first potential limitation of the review is that we excluded articles based on title/abstract screening that did not provide evidence of presenting an SDM-model. We may therefore have missed models. Second, the first criterion in the assessment of full-text articles was if they had gone through external peer-review. This criterion was difficult to apply at times, as information was lacking in this respect. We therefore chose an inclusive strategy and may have included articles that have not gone through external peer-review. Third, for some models it was difficult to distinguish what the authors saw as context and what as integral to the SDM-process. Also, it was sometimes difficult to determine from the description what the authors considered to be essential to the SDM-process and what was for example, an example of possible behaviour in the context of SDM.

The existence of SDM-models that vary in emphasis does not seem problematic to us per se. What an SDM-process exactly entails may differ by healthcare setting, and it may thus be helpful to have different models and choose the one that fits one’s purposes best. Striving for one unified model may even be unrealistic and counterproductive. Also, existing models may be adapted or extended if this proves useful. However, striving for consensus on the core of what SDM is, is desirable to align research, training, and implementation efforts. The pursuit of consensus begs the question as to whom should ideally be involved in deciding on the essence of SDM. Until consensus is reached, we call authors to report the model they use, whichever it is. Being explicit about the SDM-model used is necessary to develop SDM measures, understand results on the occurrence of SDM and its effects, to develop and implement interventions, and for training and policy purposes. When developing an intervention, it is also important to report whether the intervention targets one or more components of the SDM-process. For healthcare professionals who aim to share decisions with their patients, it is good to realise that there is no consensus in the field, only that certain components seem more key to SDM than others. Our SDM-map is a practical visual tool to easily identify the components seen as most relevant when enacting SDM in clinical practice, what components may be of more or less relevance to a particular healthcare setting and provides a basis for what should be included in training and decision support interventions.

Alizadeh, S., & Chavan, M. (2015). Cultural competence dimensions and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Health and Social Care, 24(6), e117-e130. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12293

Many countries are becoming increasingly culturally diverse as a result of migration and globalisation. In these countries, service providers are challenged to understand and address the cultural and linguistic needs of diverse populations. This diversity requires service suppliers to be aware of their customers’ cultural needs and to be able to provide them with culturally congruent services (Stauss & Mang 1999, Sharma et al. 2009). However, the unequal burden of disease and mortality borne by ethnic patients has been extensively reported in multicultural countries (Smedley et al. 2003, Weerasinghe 2012). As one of the most critical industries, the health sector should be well-equipped to address the growing diversity among patients as it must deliver equal high-quality care to patients of all cultural backgrounds (Campinha-Bacote 2002, Harris 2010). While the causes of health disparities are not clear, factors such as genetics, social and economic conditions, insurance coverage, provider knowledge and access issues may be among the determinants. In addition, cultural and linguistic differences between patients and health professionals which result in poor communication between them is considered another significant contributor (Smedley et al. 2003, Thomas et al. 2004, Fisher et al. 2007). In this regard, the cultural competence of health practitioners is proposed as a solution for providing equal and high-quality care to all groups of patients and as a way of reducing disparities and improving patient outcomes (Campinha-Bacote 2002, Betancourt et al. 2003, Henderson et al. 2011). However, after years of attempted implementation of cultural competence in the healthcare context, there are still debates on how to define and operationalise this construct (Suarez-Balcazar et al. 2011). Moreover, insufficient evidence on the efficacy and effectiveness of cultural competence may hinder the infusion of this concept into healthcare organisations (Hayes-Bautista 2003).

A few reviews on cultural competence frameworks have been published that identify the proposed definitions and components of cultural competence (Shen 2004, Bhui et al. 2007, Spitzberg & Changnon 2009, Andrews et al. 2010).

However, in these reviews, as the selected models are related to either the field of business or healthcare, the authors do not review cultural competence frameworks at an aggregate level. We believe that in reviewing definitions and components of cultural competence, excluding frameworks related to either of these fields may inhibit scholars and practitioners in one field from applying well-designed models developed in another field.

This issue has also been stressed by Anand and Lahiri (2009). They advised healthcare scholars to consider robust cultural competence models generated for non-healthcare sectors. For example, they recommended employing a well-developed model produced by Deardorff (2006) in which only those elements of intercultural competence that all of the experts agreed on were included.

In addition, some of the authors do not differentiate between individual-level and organisational-level guidelines and frameworks for cultural competence. Reviewing models related to organisational cultural competence together with models specifying characteristics of culturally competent individuals may be problematic and may hinder the effective comparison of the frameworks. Furthermore, the extant reviews do not include some of the latest conceptual models. Thus, there is a need for an up-to-date review that comprehensively identifies and appraises individual-level cultural competence frameworks. It must be noted that solely developing inclusive frameworks cannot lead to the effective implementation and realisation of practical outcomes in an important industry such as healthcare. The overall purpose of this paper was to educate researchers about recent cultural competence models and draw their attention to the necessity of investigating the effectiveness of cultural competence and applicability of the proposed frameworks and scales in practical situations. Thus, in this paper, we also assess studies in which cultural competence models and measures are used to examine the impact of provider cultural competence on patient outcomes. This may assist researchers to apply better designed and more frequently employed models and assessment tools in future studies. Conducting more rigorous empirical studies and finding more dependable evidence on the efficacy of cultural competence may facilitate establishing and implementing cultural competence policies in the healthcare sector.

In detail, this particular review aims to appraise a wide range of cultural competence frameworks used in multiple fields to realise how cultural competence has been operationalised and what dimensions have been incorporated in recent models. Additionally, it intends to explore how these conceptual models have been designed and validated. Moreover, this review aims to identify how frequently these cultural competence models have been utilised to evaluate the efficacy of cultural competence in the healthcare context and whether sufficient evidence exists with regard to the impacts of cultural competence on patient outcomes.

Therefore, we identify conceptual models that represent attributes of culturally competent providers and studies in which the relationship between caregivers’ cultural competence and patient outcomes is investigated. These outcomes may include any of the following subjects that have been broadly mentioned in the healthcare literature: (i) increased numbers of patients seeking treatment; (ii) lower rates of morbidity and mortality; (iii) increased adherence to treatment; (iv) higher level of trust; (v) increased feelings of self-esteem; (vi) improved health status; and (vii) greater satisfaction with care (Kim-Godwin et al. 2001, Suh 2004). This review can aid researchers in selecting appropriate conceptual models and measurement tools for assessing providers’ cultural competence in the healthcare sector, and to explore whether culturally competent providers can lead to improved outcomes for clients.

Methods

This review was conducted focusing on several questions. As noted earlier, this review shows what dimensions have been proposed to operationalise and measure cultural competence and how the authors developed these frameworks. Moreover, it specifies how frequently these models have been employed in empirical studies and explores whether sufficient evidence exists to verify the efficiency of cultural competence in practical cases. A comprehensive literature search was accomplished to retrieve all relevant articles. The process of the review is explained in the following sections.

Data sources and search strategy

In March 2013, we searched the following databases: EBSCOhost, Springerlink, Emerald, ScienceDirect, SAGE Journals Online, Proquest, Web of Science, NLM Gateway, Medline/Ovid, Medline/PubMed, IngentaConnect and CINAHLPlus. In addition, we also manually searched the bibliographies of key articles in several journals such as the Journal of Transcultural Nursing, the Journal of Cultural Diversity, and the International Journal of Intercultural Relations. We designed search strategies, specific to each database, to maximise sensitivity. For example, for the EBSCOhost search, we used the following combination: (“cultural competence” OR “cultural competency” OR “intercultural competence” OR “intercultural communication competence” OR “multi-cultural competence” OR “cross-cultural competence” OR “culturally competent communication”) AND (“Model” OR “Framework” OR “Schematic design”). A similar search template was used by combining cultural competence terms and patient outcomes such as “patient satisfaction”, “patient trust”, “quality of healthcare”, “adherence to treatment”, “health status” and “feelings of self-esteem”.

The types of references used in this paper include journal articles, reports and dissertations. All studies referenced herein were published between 2000 and 2013. A few systematic reviews on cultural competence dimensions and outcomes have been conducted between 2004 and 2009; however, as mentioned earlier, the authors did not include both health-related and business-related conceptual models and they did not include some frameworks developed after 2005. Thus, to include more recent models and assessment tools, we excluded the papers published before 2000. This does not imply that research conducted before 2000 in this discipline was not significant, it just clarifies that this paper specifically conducted an in-depth review of literature published during 2000–2013.

Study selection

We excluded articles or dissertations that were not written in English or that were published before 2000. This date was applied to ensure relevance of the latest conceptual models, and to include the most recent evidence regarding cultural competence outcomes. Additionally, we excluded items that did not have a full text available for review.

The criteria for including studies were that they:

Represent conceptual frameworks for cultural competence. The conceptual model refers to a visual presentation of variables that interrelate with one another as perceived by the researcher. Transforming theories into a visual format helps identify key intersections of perspectives that are often missed in purely narrative readings (Spitzberg & Changnon 2009). Schematic frameworks, by their nature, are more explicit than narrative models and the differences between them are easier to understand in terms of how the key concepts and constructs and the relationships between them are configured and analysed (Pearce 2012). Thus, to make a clear comparison between conceptual models, only schematic frameworks were included in this review.

Present empirical data regarding the link between providers’ cultural competence and patient outcomes.

Data extraction

We printed the title and abstract of all citations identified through the literature search, and two researchers independently reviewed the title and abstract for eligibility to confirm relevance to the research objectives. During the review of abstracts, papers which did not either introduce new conceptual models or quantitatively examine relationships between provider cultural competence and patient outcome were excluded. We designed our process such that no abstract would be excluded based on the opinion of only one reviewer. When reviewers agreed that a decision regarding eligibility could not be made because of insufficient information, the full article was retrieved for review and disagreements on the extracted data were resolved by consensus.

Data synthesis

Data are presented narratively to describe the characteristics of the identified cultural competence frameworks. Likewise, for the second group of papers (empirical studies), we conducted a narrative synthesis of the data. A quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis) was not possible due to the heterogeneity of research design, participants, types of reported outcomes and the employed measures for assessing the same outcome. Moreover, as the number of practical studies investigating the impact of cultural competence on patient outcomes was not sufficient to gain a good power, the narrative analysis was preferred to the meta-analysis (Borenstein et al. 2009).

Results

We screened 1204 citations published up to March 2013. Of this, 18 publications were found to meet the first inclusion criterion and 13 articles fulfilled the second criterion.

Cultural competence conceptual models

Field of research

In the present review, we categorised conceptual models into two contexts: healthcare and business. Nine of the identified models were developed specifically for the healthcare context and were mainly targeted at nurses, physicians, rehabilitation teams, psychiatrists and counsellors. Another group of models was developed for settings other than healthcare, which, we named generally as being from a business context. These models were tailored for fields such as international business or international management, education/universities, library and information science, and the army.

All of the health-related models used the term ‘cultural competence’, while the business-related frameworks used various terms such as ‘cultural competence’, ‘intercultural competence’, ‘intercultural communication competence’, ‘cultural intelligence’, ‘cross-cultural competence’ and ‘intercultural competency’. The term ‘cultural competence’ is apparently more popular in the healthcare field than in the business field. Two of the business-related models used the term ‘cultural intelligence’. As Kim (2008) stated, ‘motivational and behavioural factors are not actual elements of intelligence’, and therefore, because the label cultural competence is more appropriate in this situation, we included these two models as cultural competence models in this paper.

Definition and dimensions of cultural competence

Generally, the authors considered cultural competence as the ability to work and communicate effectively and appropriately with people from culturally different backgrounds. While appropriateness implies not violating the valued rules, effectiveness means achieving the valued goals and outcomes in intercultural interactions (Spitzberg 1989). Most of the authors emphasised that cultural competence is an ongoing process, not an endpoint event, meaning that competency capability can be continuously enhanced over time.

Cultural awareness, cultural knowledge and cultural skills/behaviour were posited as the most important elements of cultural competence in the majority of the frameworks. In some models, cultural awareness and cultural knowledge were combined as one element of cultural competence, namely the cognitive element. Generally, cultural awareness was defined as an individual's awareness of her/his own views such as ethnocentric, biased and prejudiced beliefs towards other cultures, and cultural knowledge was pronounced as the continued acquisition of information about other cultures. Cultural skills or behaviour was described as the communication and behavioural ability to interact effectively with culturally different people. In the business context, these skills mainly stressed communication skills, while in the healthcare context, the ability to make an accurate physical assessment and collect health data of culturally/ethnically diverse patients was also included.

Apart from the above-mentioned dimensions, two other factors, namely cultural desire/motivation and cultural encounter/interaction, were replicated across several models. Cultural desire was defined as an individual's motivation or willingness to engage, participate and learn about cultural diversity and to raise his/her cultural awareness, knowledge and skills. Cultural encounter referred to face-to-face contacts or other types of interactions with culturally different people.

Extra components in the cultural competence models

Nearly all of the authors emphasised the effectiveness or appropriateness of cultural competence in the definitions or descriptions of the models. Although effectiveness refers to the outcomes of cultural competence, in only four conceptual models, outcomes of cultural competence were included. Two of these models were related to healthcare and indicated outcomes such as improved patient quality of life, patient satisfaction, adherence to treatment and provider performance. The remaining models were related to the business field and depicted outcomes such as enhanced job performance, personal adjustment and interpersonal relationships for individuals working in culturally different settings.

In addition to the components of cultural competence and the outcomes, other elements are evident in several models. These are generally categorised as environmental or organisational factors. The authors of these models believed that these factors can affect outcomes and influence the degree to which a culturally competent person can work successfully in a culturally different context. According to this perspective, intercultural outcomes are not merely determined by the capability of an individual, but are shaped by the larger context as it can affect outcomes directly and indirectly by influencing the individual's behaviour. One such variable is cultural distance, which is defined as the actual or perceived discrepancy between one's own cultural practices and values and those of another culture. A very culturally different environment may cause individuals to experience high levels of stress, and may undermine their aptitude to adapt effectively (Johnson et al. 2006). Institutional ethnocentrism promotes the home culture's ways of behaving and accomplishing tasks, and accordingly, this factor was included in one model to show its negative impact on an individual's ability to respond appropriately to cultural differences in the workplace (Johnson et al. 2006). Institutional ethnocentrism and cultural distance can deter an individual from using his/her cultural knowledge and skills to achieve favourable outcomes (Abbe et al. 2007). Moreover, adoption of cultural knowledge and skills can be facilitated or hindered by the degree of organisational support where the service providers work. Organisational support varies in the degree to which agencies encourage or impede cultural competence through policies, procedures and allocation of resources in everyday practices. Thus, organisational support was incorporated into one of the models as an important factor in determining an employee's capability to achieve desirable outcomes and deliver culturally competent services (Balcazar et al. 2009).

Design methods and assessment tools

The authors mainly developed their conceptual models by reviewing existing definitions and frameworks. Only one author developed their model by using a number of expert views through a Delphi study.

For eight of these models, we could not find any assessment tools. Thus, we concluded that these frameworks were not tested quantitatively by the original inventors or by other scholars. For 10 models, we found related measuring instruments. All of the assessment tools developed by the original authors of the models were self-rating instruments that used individuals’ personal perceptions to measure their level of cultural competence. Among the proposed assessment tools, only one scale was a client-rating instrument that measured the cultural competence of an employee by obtaining the perspective of the clients.

Empirical studies on cultural competence outcomes

Thirteen papers satisfied the second inclusion criterion. Patients who received services such as counselling, aged care, emergency treatment or treatment for hypertension, diabetes and HIV were surveyed in these studies. The association between provider cultural competence and outcomes such as patient satisfaction, patient trust, adherence to treatment and health index was examined in these papers. Patient satisfaction was the most popular outcome measured in 12 studies. Two studies investigated the link between provider cultural competence and patient trust, whereas only one study examined the relation between provider cultural competence and patient health index, such as blood pressure, and one study examined if higher cultural competence leads to higher adherence to treatment.

Study characteristics and samples

All of the empirical studies were conducted in the United States. Only two studies included a large sample size of patients, while the others had relatively small to medium sample sizes that ranged from 50 to 450 clients. The majority of the patients belonged to one of four ethnic groups: Caucasian Americans, African Americans, non-white Hispanics or Asian Americans. Six studies examined the cultural competence of the providers through the perspectives of the patients. In seven studies, the providers’ self-rated cultural competence was used for analysis. Two studies used both self-reporting and patient-reporting tools to measure providers’ cultural competence. Four studies used the assessment tools related to some of the conceptual models described in Table 1. In three of these studies, self-assessment tools, namely Inventory for Assessing the Process of Cultural Competence (IAPCC) and Cultural Competence Assessment, which were related to Campinha-Bacote's and Schim's models, respectively, were used to evaluate providers’ cultural competence. Only one of these studies used a patient-assessment tool to measure the cultural competence of the caregivers. This scale was developed by Lucas et al. (2008) and was based on Sue's conceptual model. Moreover, in nine studies, the authors used assessment tools that were not generated based on a specific model. Three assessment tools incorporated the three dimensions of cultural competence (awareness, knowledge and skills) (Constantine 2002, Fuertes et al. 2006, Paez et al. 2009), while in six papers, not all of these dimensions were included in the measuring instruments (Cook et al. 2005, Thom & Tirado 2006, Ahmed 2007, Kerfeld et al. 2011, Damashek et al. 2012, Saha et al. 2013).

Impact of cultural competence on outcome variables

No significant relationship between provider cultural competence and patient satisfaction was found in two studies; in three studies, this link was partially confirmed, and in seven studies, the results indicated small to moderate associations. Additionally, only one of the two studies investigating the link between provider cultural competence and patient trust substantiated this association.

Methodological quality of empirical studies

The methodological quality of the 13 empirical papers was appraised independently by two authors using the revised version of Estabrooks’ Quality Assessment and Validity Tool for Cross-sectional Studies (Squires et al. 2011). Differences in quality assessment were resolved by discussion. The modified tool consists of 11 criteria which examine sampling, measurement and statistical analysis. The quality score of each empirical study included in this review was calculated by dividing the total number of points obtained by the total number of possible points, yielding a score between 0 and 1 for each study. The studies were then classified as weak (<0.50), moderate-weak (0.51–0.65), moderate-strong (0.66–0.79) or strong (0.80–0.10). Five studies were of weak methodological quality, and five had moderate-weak strength. Three papers had moderate-strong quality, while no paper was rated as strong (quality score >0.80).

Discussion

In the first group of reviewed articles, characteristics of culturally competent individuals were proposed for both business and healthcare environments. The second group of the reviewed articles investigated the link between health practitioners’ cultural competence and outcomes such as patient satisfaction and trust.

The reviewed studies revealed that there is general agreement among the researchers in the field of healthcare regarding the term cultural competence. Despite the slight differences in defining cultural competence, there is consensus regarding the continuous nature of this concept and with respect to the three components of cultural competence: cultural awareness, cultural knowledge and cultural skills. However, additional components such as cultural desire/motivation and cultural encounter/interaction were also incorporated in several conceptual models and assessment tools. Including these additional dimensions may assist researchers to assess cultural competence of individuals more accurately in future studies.

Moreover, this study found that most of the conceptual frameworks were developed based on literature reviews and on authors’ personal experiences and that notably few efforts have been made to produce conceptual models and assessment tools based on the perspectives of leading experts on cultural competence or based on methods such as Delphi. Furthermore, in healthcare-related studies, the authors did not usually analyse or cite the business-related models and vice versa. However, some of the well-developed frameworks in the business field were recommended to be used in the healthcare context. For instance, Anand and Lahiri (2009) advised healthcare scholars to use a framework generated by Deardorff (2006) in which only those elements of intercultural competence that all of the experts agreed on were included.

As not many of the proposed models have been sufficiently validated and tested, there is a need for more empirical studies to assess the strength of the proposed frameworks. Most of the assessment tools created by the models’ original authors were self-rating tools. In addition, half of the reviewed studies investigating the outcomes of cultural competence in the healthcare field adopted self-reporting cultural competence instruments. Although studies showed good reliability of a number of these tools, some researchers in the fields of both business and healthcare have voiced concerns over the potential shortcomings of the self-rating assessment tools. For instance, Thom and Tirado (2006) posited that patient-reported cultural competence may be more strongly associated with the outcomes of care than with the results of self-reporting. Moreover, Moleiro et al. (2011) found that individuals tend to overestimate their level of intercultural competence, a factor that may mislead managers as to their employees’ actual abilities to work with culturally diverse clients. Furthermore, Deardorff (2006) recommended using qualitative interviews or observations combined with a quantitative method to measure the cultural competence of individuals.

Most of the reviewed empirical studies only considered patient satisfaction as the patient outcome. Very few papers reported the impact of providers’ cultural competence on patient trust and health status and no studies investigated outcomes such as adherence to treatment or health service utilisation. Additionally, the findings of these enquiries were contradictory. While some indicated a meaningful statistical relationship between provider cultural competence and patient satisfaction and trust, others provided no support for these associations. Furthermore, the majority of the reviewed empirical studies suffer from poor methodological quality which limits the strength and generalisability of the research findings. Although theory and logic suggest abundant benefits from cultural competence, without empirical support obtained from high-quality and dependable investigation, it may be difficult to convince managers to invest time and money in promoting cultural competence within their organisations. Hence, more attempts are needed to examine the impact of providers’ cultural competence on various patient outcomes and in future studies, better sampling methods, larger participant numbers and more accurate statistical analysis should be adopted.

Most of the reviewed models and all of the empirical studies were developed and conducted in the United States. Jirwe et al. (2009) emphasised that cultural competence frameworks may reflect the sociocultural, historical or political context in which they were developed. As countries usually have different sociocultural demographics, there is a need to develop and test new conceptual models in other multicultural countries. Additionally, more empirical studies should be conducted in different countries to explore whether the cultural competence of service providers, especially health practitioners, affects outcomes for clients.

Limitations